Abstract

With the completion and near completion of many malaria parasite genome-sequencing projects, efforts are now being directed to a better understanding of gene functions and to the discovery of vaccine and drug targets. Inter- and intraspecies comparisons of the parasite genomes will provide invaluable insights into parasite evolution, virulence, drug resistance, and immune invasion. Genome-wide searches for loci under various selection pressures may lead to discovery of genes conferring drug resistance or encoding for protective antigens. In addition, the Plasmodium falciparum genome sequence provides the basis for the development of various microarrays to monitor gene expression and to detect nucleotide substitution and deletion/amplification. Genome-wide profiling of the parasite proteome, chromatin modification, and nucleosome position also depend on availability of the parasite genome. In this brief review, we will highlight some recent advances and studies in characterizing gene function and related phenotype in P. falciparum that were made possible by the genome sequence, particularly the development of a genome-wide diversity map and various high-throughput genotyping methods for genome-wide association studies (GWAS).

Keywords: Malaria, microarray, genome diversity, SNP, recombination, comparative genomics.

MALARIA PARASITES AND GENOMES

Malaria is one of the most important tropical parasitic diseases in humans, causing great morbidity and mortality in many developing countries. Approximately 300–500 million clinical cases and ~1 million deaths are reported each year [1]. Human malaria is caused by five species of the Plasmodium parasites, namely Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium malariae, and Plasmodium knowlesi [2]. Among these, P. falciparum causes the most serious forms of the disease. The life cycle of the malaria parasite involves multiple tissues and different stages (sexual and asexual) inside two distinct hosts, mosquitoes and humans. Within its complicated life cycle, the parasite has a diploid genome for a short period of time during its development in the mosquito vector and has a haploid genome throughout the majority of its life cycle. The haploid parasite is amenable to the application of many genetic and genomic tools that play an important role in functional genomics research.

P. falciparum has 14 chromosomes containing ~23 million base-pair nucleotides with high AT content (~82%) and is predicted to have approximately 5,500 genes [3-5]. The number of protein-coding genes in P. falciparum is comparable to those in free-living yeasts, but the latter organism has a considerably smaller genome in comparison to P. falciparum. In addition to differences in coding capacity, the P. falciparum genome also has a greater number of hypothetical proteins (~60%) with limited homology to genes with known functions; the functions of these proteins are therefore unknown. Additionally, approximately 1/4 of the current gene models in the P. falciparum genome database may contain errors [6,7].

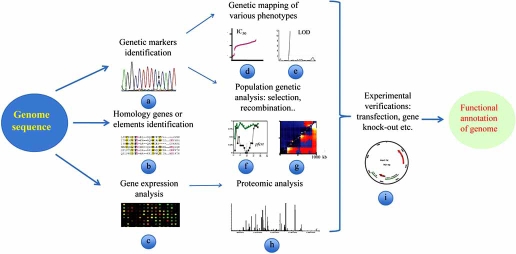

Various genomic approaches have been applied to define possible gene functions since the completion of the P. falciparum genome sequencing project in 2002 [5] (Fig. 1), and significant progress has been made. Here we briefly review some of these developments, focusing on progress in genetic mapping using high-throughput genotyping.

Fig. (1).

Genetic mapping, comparative genomic analysis, and combination of transcriptomic, epigenomic and proteomic approaches can play important roles in understanding gene functions in P. falciparum.

a. Sequence analysis to identify genetic polymorphisms; b. sequence comparison to search for homolog genes or elements; c, microarray chips to evaluate the gene expression at mRNA level; d, e. analysis of different phenotype and genotype data to locate candidate genes/loci associated with drug resistance and other traits; f, g. population genetic analysis to detect genetic loci under selection or with elevated recombination frequency; h. protein expression analysis and association with developmental stages; and i. predicated functions of candidate genes can be studied using genetic knock-out and other methods.

GENOME DIVERSITY AND GENETIC MAPPING

Genetic diversity is considered to contribute to the majority of phenotypic differences; therefore the function of a gene can be inferred either from the linkage or association of genetic polymorphisms to differences in phenotypes [8,9]. Genetic crosses have been successfully applied to identify genes in P. falciparum involved in drug resistance, such as pfcrt in chloroquine (CQ) resistance [10-12], pfdhfr in pyrimethamine resistance [13], and most recently pfrh5 in determination of the species-specific pathway of P. falciparum invasion [14]; however, the cost and intensive lab work of this approach have limited its application for larger-scale functional analysis in human malaria parasites.

With multiple technologic advances, particularly development of high-throughput genotyping since the publication of the P. falciparum genome, the genetic markers used for mapping purposes in P. falciparum have shifted from the microsatellite (MS) to single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs). A project of systematic identification of SNP markers in the P. falciparum genome was initiated approximately 8 years ago [15,16]. By resequencing approximately 20% of the genome from four parasites (HB3, Dd2, 7G8, and D10) that originated from different geographic locations, ~ 4,000 SNPs were identified after alignment of the sequences with that of 3D7 that was available in the public databases. With the joining of two groups from major sequencing centers at the Broad Institute and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, more parasite genomes have been re-sequenced, and a much larger data set is now available [17,18]. Currently, approximately 180,000 SNPs have been identified from 18 full or partially sequenced P. falciparum strains (http://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/), although some of the SNPs could be errors from sequence alignments that required further verification. Additional strains from global populations are being sequenced using parallel sequencing, which will provide information for better understanding of parasite genome diversity, population structure, and gene functions [19].

In addition to the resequencing approach, high-density tiling arrays have also been developed to study gene expression and genome diversity in malaria parasites [20-23]. Nucleotide change—including nucleotide substitution, deletion, and insertion—results in a reproducible loss or reduction of hybridization signal and therefore allows identification of the region with genetic changes. Several studies have used microarrays to detect nucleotide substitution and copy number variation (CNV) [20,24]. Approximately 20,000 single–feature polymorphisms (SFPs) from 14 field isolates and laboratory lines were identified using an Affymetrix array containing 298,782 oligonucleotide probes [20]. A similar study using a higher-density array (PFSANGER array) containing 2.5 million probes also detected more than 40,000 SFPs from five P. falciparum isolates [21]. Moreover, high-throughput SNP typing arrays have been developed for studying parasite population and genetic mapping. Two different platforms are currently available: one utilizes a standard Affymetrix hybridization array [27], and another is based on molecular inversion probe (MIP) technology [25]. Both chips can interrogate ~3000 SNPs and are being upgraded to larger-scale chips that can detect more SNPs. Indeed, a limited numbers of upgraded MIP array chips containing ~8000 SNPs is currently available for public uses at MR4 (http://www.mr4.org/). The Affymetrix standard hybridization chip has been applied to evaluate linkage disequilibrium (LD) and natural selection near the pfcrt loci on chromosome 7 in parasite populations from different continents [24], and the MIP array has been used to genotype parasite isolates that have different phenotypic variation. The genotypic data obtained from the MIP array was applied to scan the parasite genome for population recombination events, recent positive selection signatures and association of genetic loci with multiple drug-resistant phenotypes in P. falciparum [25]. Undoubtedly, microarrays will play an important role in studying parasite genomes and in genetic mapping in the near future.

Significant insights have been gained in the population structure of malaria parasites as well as mapping candidate genes using currently available SNPs. Population structure or admixture can potentially lead to both false-positive and false-negative results in association studies; thus, structure analysis should be investigated prior to an association study. Analysis of SNPs from chromosome 3 among 99 globally collected parasites showed that malaria parasites could be clustered into different major groups according to their geographic origins independent of time of collection [26]. Similar results were also obtained in a study using the Affymetrix hybridization SNP array, which showed that continental boundaries between parasite populations gave rise to most population structure [27]; however, caution should be exercised in interpreting population structure results when using markers that are likely under selection. For example, SNPs from 49 transporter genes in P. falciparum, many of which were likely under drug selection, clustered African parasites into two groups according to parasite response to CQ [26], whereas SNPs in the gene encoding apical membrane antigen 1 (pfama-1), a target of host immunity, grouped parasites into six populations that were independent of geographic origin [28]. Therefore, results of population structure analysis will be influenced by the type and nature of genetic marker used.

Recombination can play an important role in shaping the parasite genome. For example, recombination changes the size of the LD region (or haplotype block) in the genome and generates new parasite variants that may evade host immunity. Locating recombination hotspots or coldspots in the genome could therefore provide insight into genome evolution and parasite transmission dynamics. Studies of single chromosome [26] as well as whole genome [25] showed that recombination hotspots were located largely at the ends of the chromosome that contains many multifamily genes such as var, rifin, and stevor. Many of these recombination hot or cold spots appeared to be conserved among parasite populations, although the population recombination rate varied greatly, ranging from ~400/mb in American parasites to over 105/mb in African parasites. Variation of recombination rate in different populations has been shown to affect the size of LD and haplotype blocks in the genome and therefore should be considered in the design of any association studies [26].

Another important source of information to help define gene function is determining genetic loci that are under recent positive selection. As shown in the human genome, positively selected genes can be classified into groups by broad biologic processes of gene function such as gametogenesis, spermatogenesis, fertilization, metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, and phosphates, and vitamin transport [29-31]. For malaria parasites, systematic evaluation of selection have been performed at some candidate genetic loci associated with drug response, such as pfcrt [32] and dhfr [33], as well as at the whole genome level [25]. As expected, genes that confer drug resistance are under strong positive selection, although the strength of selection may vary among different geographic samples. For example, a ~200-kb region containing pfcrt was shown to be under positive selection in a population isolated from Africa and Southeast Asia [32], whereas only ~70 kb was under such selection in a Laotian parasite population [33]. Interestingly, several novel genetic loci, including ABC transporters, an iron transporter, a member of SURFIN and some conserved Plasmodium proteins, were found under significant positive selection by genome-wide scan [25]. In addition to drug selection, host immunity is also a strong force in shaping the parasite genome, such as generation of polymorphisms in antigenic gene families (diversifying selection). Therefore, screening of highly polymorphic genes in the P. falciparum genome may lead to discovery of novel vaccine candidate genes [34], although polymorphism in vaccine candidates may also pose some challenges for vaccine development.

In addition to SNP markers, CNV can also be informative in characterizing gene functions. Copy number changes have been linked to various diseases or biologic processes and can contribute to phenotypic variation in many organisms [35,36]. In P. falciparum, recent studies have shown that amplification of pfmdr1, pfgch1, and pfdxr may be important for parasite resistance to mefloquine, antifolate drugs, and fosmidomycin, respectively [20,24,37,38].

To date, genome-wide analyses of genetic diversity in P. falciparum has led to identification of several candidate genes or loci for novel vaccine and drug targets. It is expected that many more such loci will be discovered in the near future with the increasing availability of phenotypic and genomic data. In particular, the differences in parasite responses to larger number of chemical compounds can be identified as phenotypes for mapping parasite targets of the chemical compounds and for inferring gene functions [39].

COMPARATIVE GENOMICS AND HOMOLOGOUS GENE SEARCHES

Along with the dramatic efforts being put forth to search for genomic diversity, comparative analysis of the parasite genome sequences to discover homologous genes plays an important role in elucidating the functions of many predicted proteins. Searches based on biased G/C content and RNA folding potential have led to identification of a large number of noncoding RNA (ncRNA), including splicing RNA, small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA), and telomerase RNA in P. falciparum [40,41]. In addition to ncRNA with known functions, several candidate genes appear to be specific to Plasmodium spp. and lie adjacent to members of the var gene family, possibly contributing to the control of allelic expression of this multigene family. Alternatively, these genes could be acting as recombination hotspots, generating diversity that can contribute to immune evasion. Although no parasite-encoded microRNA (miRNA) genes have been found in P. falciparum to date and the function of miRNA-mediated control on gene expression in malaria parasites remains controversial, analysis of potential RNA folding using RNAmicro [42] revealed five novel ncRNA that might act as precursors for miRNA [41]. Further studies are needed to illustrate the role of these ncRNA in gene regulation.

Another example of the use of homology search to characterize gene functions is that of the erythrocyte binding-like (EBL) and reticulocyte-binding-like protein (RBL) gene families that are involved in parasite invasion of erythrocytes. Both of the gene families consist of multiple members located on different chromosomes of P. falciparum or other Plasmodium spp. Characterization of these families has been greatly enhanced by use of homology searches among different Plasmodium spp. A detailed summary of the functional characteristics of these genes can be found in excellent reviews elsewhere [43-45]. More recently, a gene family of intramembrane serine proteases encoded by eight different orthologous genes was discovered in the P. falciparum genome [46]. This gene family, termed rhomboid-like proteins (ROMs), is likely involved in host-parasite interaction and is present in the genomes of all Apicomplexan parasites whose genomes have been sequenced. Other families of essential proteases, including those implicated in parasite egress from the erythrocyte such as falcipain-2, plasmepsin II, and a family of putative papain-like proteases termed SERA, have been identified using homology search [47,48]. These proteases may provide key targets for development of new chemotherapeutic treatment strategies.

Comparative genetics have also been important in locating genetic regulatory elements, particularly the apicomplexan AP2 (ApiAP2), in the P. falciparum genome [49,50]. These discoveries have drastically changed the landscape of transcriptional regulation in P. falciparum. More than 20 ApiAP2 genes have been identified on different chromosomes, all of which were previously annotated as hypothetical proteins [51]. Detailed investigation of two members of this family, PF14_0063 and PFF0200c, suggests an essential role in regulating parasite development [50]. These data, combined with large catalogs of potential cis-acting sequences obtained from in silico discovery of transcription regulatory elements [52], have enhanced our understanding of the role of transcriptional regulation in P. falciparum.

Comprehensive comparative genomics have opened the door for other newly emerging fields in P. falciparum, such as secretome and epigenome research. Through close examination of known exported proteins in P. falciparum, conserved motifs termed Plasmodium export element (PEXEL) and vacuolar transport signal (VTS) have been identified from the parasite genome [53,54]. These elements are necessary for export of hundreds of proteins from the parasites that serve to remodel the host erythrocyte [53-57]. The role of these unique modifications on the infected erythrocyte has already been examined by genetic knockout and functional screens [55]. Molecules with secretion signals might be evaluated for antivirulence targets, as some of these genes are important in knob formation and/or involved in the increased rigidity of the infected erythrocytes [55]. A central portal through which most or all of these exported proteins are transported through the erythrocyte has been recently characterized [58]. Further investigations into the functions of these exported proteins are needed to gain additional insight into the P. falciparum secretome.

VARIATION IN GENE EXPRESSION AT mRNA AND PROTEIN LEVELS

Identification of the genes involved in epigenomic control in the P. falciparum genome, such as histone acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation [59-61], has brought a new level to our understanding of parasite biology and the discovery of new drug targets.

Gene functions can also be predicted by monitoring the dynamic of mRNA or protein expression in combination with related phenotypes or developmental stages. Prior to availability of the whole genome sequence, methods for measuring gene expression level in P. falciparum were mostly based on gene-by-gene methods such as northern blot, reverse transcriptase-PCR, and complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries. Although these methods have contributed significantly to our understanding of gene expression and function, DNA microarray—which utilizes the genomic sequence for designing oligonucleotide probes—becomes the favored platform for studying gene expression in malaria parasites due to its higher resolution, reproducibility, and coverage. A microarray transcriptome analysis identified clusters of genes with similar expression patterns that were differentially regulated across the life cycle [62]. Further analysis using an improved clustering approach called ontology-based pattern identification (OPI) in combination with evidence-based annotation revealed 320 gene clusters representing various biologic processes, leading to functional predictions for hundreds previously uncharacterized malaria genes [63-65]. Comprehensive comparison of in vitro [52,62,66,67] and in vivo [68] gene expression patterns among different parasite isolates as well as expression level polymorphisms (ELPs) in a genetic cross [69,70] have allowed identification of hundreds of transcription regulatory elements and regulatory hotspots. Interestingly, although both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that gene transcription in P. falciparum parasites is rigidly programmed throughout the erythrocytic cycle, the expression profiles showed dramatic differences for parasites grown in these two different environments [68]. At least three distinct physiologic states, which related to glycolytic growth, starvation response, and a general stress response, were found in P. falciparum parasites isolated directly from patients; only one state could match the in vitro parasite life stage [68]. A recent study suggested, however, that the "hidden" state of expression might be, in fact, transcripts from gametocytes [71].

The determinants of these transcriptional regulations remain elusive, although increasing identification of genetic regulatory elements and expression quantitative loci (eQTLs) has narrowed down the genetic regions for further investigations. Comparison of the gene expression profile of genetically modified parasites such as drug-selected [72-74] or gene knock-out parasites [75] with their parental wild-type parasites will allow identification of genes that interact with those functionally modified genes.

The mechanism of gene expression variation has been linked not only to DNA sequence alterations but also to epigenetic modifications and other mechanism in P. falciparum [76-78]. The most extensively studied gene family is the var gene family, which encodes hypervariable surface antigens and displays mutually exclusive expression in infected red blood cells [79,80]. Switching of gene expression states from active to silent or vice versa may be associated with chromatin modifications [77,81], locations of active genes in the nucleus [82,83], and presence of regulatory introns [84,85]. Histone acetylation has been associated with gene activation [82,83], whereas trimethylation of lysine 9 of histone H3 (H3K9me3) was found to silent the genes in P. falciparum parasites [81,86]. Genome-wide analysis of histone 3 modification using a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay revealed the cycle-regulated H3K4me3 and H3K9ac at asexual developmental stages in P. falciparum [87,88]. Disruption of one of the key genes in chromatin modification (pfSir2) that encodes a histone deactylase caused changes in the H3K9me3 profile, and inhibitors of this enzyme showed high potency against cultured P. falciparum parasites in vitro [89]. Given the observed differences in the epigenetic code compared with all other organisms studied, Plasmodium-specific epigenetic enzyme inhibitors could be explored for new therapeutic agents against P. falciparum [89].

Gene functions have also been predicted by large-scale comparative analysis on the protein expression level in P. falciparum. Although it can be difficult to obtain sufficient material and to prevent contamination from host cells, two large-scale studies using high-throughput proteomics have detected many stage-specific predicted gene products consistent with results from transcript profiling studies [90,91]. This genomics-based approach has also been widely applied in studies of drug targets [92-94], organelle composition [95], stage- and sex-specific gene functions [23,96,97], validation of data from genomic annotation, post-translational modifications [98,99]. With the completion of its human and insect host genome project, genomic, metabolomic and proteomic analyses of host-pathogen interactions have shed light on many malaria genes’ functions [100-102]. This important research topic has been reviewed elsewhere recently [103-105]. Combined transcriptomic, epigenetic, and proteomic data also allowed uncovering regulatory mechanisms of gene expression in P. falciparum [23,99]. With the availability of newer methodologies, analysis of expression variation at the protein level may permit investigation of protein interaction and discovery of targets for new drugs and vaccines.

FUTURE PROSPECTS

Functional genomic research in P. falciparum will undoubtedly continue to contribute greatly to our battle against this deadly parasite. As more phenotypic data become available, the ability to identify gene function will be greatly enhanced by high-throughput, genome-eide approaches. High-throughput assays for parasite phenotypes such as drug response, variation in invasion efficiency, population expression profiling, and variation in parasite metabolites can lead to gene function assignment with the use of genomic data. Moreover, next-generation sequencing methods are emerging as the dominant genomic technologies and can be applied in a variety of contexts for functional genomics research, including whole-genome sequencing, targeted resequencing, deep transcriptome analysis to complement microarray analysis, and other genome-wide approaches. In addition, application of novel genetic manipulation tools such as transposon mutagenesis (piggyBac) [106] and improved transfection methods [107] will be extremely valuable for generating functional mutations and for verifying gene functions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. We thank NIAID intramural editor Brenda Rae Marshall for assistance.

Because J.M., A.B., and X-z.S. are government employees and this is a government work, the work is in the public domain in the United States. Notwithstanding any other agreements, the NIH reserves the right to provide the work to PubMedCentral for display and use by the public, and PubMedCentral may tag or modify the work consistent with its customary practices. You can establish rights outside of the U.S. subject to a government use license.

ABBREVIATIONS

- cDNA

= Complementary DNA

- ChIP

= Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CNV

= Copy number variation

- CQ

= Chloroquine

- EBL

= Erythrocyte binding-like

- ELP

= Expression level polymorphisms

- LD

= Linkage disequilibrium

- MIP

= Molecular inversion probe

- miRNA

= microRNA

- MS

= Microsatellite

- ncRNA

= Noncoding RNA

- OPI

= Ontology-based pattern identification

- PEXEL

= Plasmodium export element

- RBL

= Reticulocyte-binding like protein

- SFP

= Single-feature polymorphism

- snoRNA

= Small nucleolar RNA

- SNP

= Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SP

= Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine

- VTS

= Vacuolar transport signal

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller LH, Baruch DI, Marsh K, Doumbo OK. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:673–679. doi: 10.1038/415673a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White NJ. Plasmodium knowlesi: the fifth human malaria parasite. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:172–173. doi: 10.1086/524889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pain A, Hertz-Fowler C. Plasmodium genomics: latest milestone. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:180–181. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aravind L, Iyer LM, Wellems TE, Miller LH. Plasmodium biology: genomic gleanings. Cell. 2003;115:771–785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner MJ, Hall N, Fung E, White O, Berriman M, Hyman RW, Carlton JM, Pain A, Nelson KE, Bowman S, Paulsen IT, James K, Eisen JA, Rutherford K, Salzberg SL, Craig A, Kyes S, Chan MS, Nene V, Shallom SJ, Suh B, Peterson J, Angiuoli S, Pertea M, Allen J, Selengut J, Haft D, Mather MW, Vaidya AB, Martin DM, Fairlamb AH, Fraunholz MJ, Roos DS, Ralph SA, McFadden GI, Cummings LM, Subramanian GM, Mungall C, Venter JC, Carucci DJ, Hoffman SL, Newbold C, Davis RW, Fraser CM, Barrell B. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;419:498–511. doi: 10.1038/nature01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu F, Jiang H, Ding J, Mu J, Valenzuela JG, Ribeiro JM, Su XZ. cDNA sequences reveal considerable gene prediction inaccuracy in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:255. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakaguri H, Suzuki Y, Katayama T, Kawashima S, Kibukawa E, Hiranuka K, Sasaki M, Sugano S, Watanabe J. Full-Malaria/Parasites and Full-Arthropods: databases of full-length cDNAs of parasites and arthropods, update 2009. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D520–525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson TJ. Mapping drug resistance genes in Plasmodium falciparum by genome-wide association. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 2004;4:65–78. doi: 10.2174/1568005043480943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su X, Hayton K, Wellems TE. Genetic linkage and association analyses for trait mapping in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:497–506. doi: 10.1038/nrg2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su X, Kirkman LA, Fujioka H, Wellems TE. Complex polymorphisms in an approximately 330 kDa protein are linked to chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum in Southeast Asia and Africa. Cell. 1997;91:593–603. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fidock DA, Nomura T, Talley AK, Cooper RA, Dzekunov SM, Ferdig MT, Ursos LM, Sidhu AB, Naude B, Deitsch KW, Su XZ, Wootton JC, Roepe PD, Wellems TE. Mutations in the P. falciparum digestive vacuole transmembrane protein PfCRT and evidence for their role in chloroquine resistance. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:861–871. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wellems TE, Panton LJ, Gluzman IY, do Rosario VE, Gwadz RW, Walker-Jonah A, Krogstad DJ. Chloroquine resistance not linked to mdr-like genes in a Plasmodium falciparum cross. Nature. 1990;345:253–255. doi: 10.1038/345253a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson DS, Walliker D, Wellems TE. Evidence that a point mutation in dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase confers resistance to pyrimethamine in falciparum malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:9114–9118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayton K, Gaur D, Liu A, Takahashi J, Henschen B, Singh S, Lambert L, Furuya T, Bouttenot R, Doll M, Nawaz F, Mu J, Jiang L, Miller LH, Wellems TE. Erythrocyte binding protein PfRH5 polymorphisms determine species-specific pathways of Plasmodium falciparum invasion. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mu J, Duan J, Makova KD, Joy DA, Huynh CQ, Branch OH, Li WH, Su XZ. Chromosome-wide SNPs reveal an ancient origin for Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;418:323–326. doi: 10.1038/nature00836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mu J, Ferdig MT, Feng X, Joy DA, Duan J, Furuya T, Subramanian G, Aravind L, Cooper RA, Wootton JC, Xiong M, Su XZ. Multiple transporters associated with malaria parasite responses to chloroquine and quinine. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:977–989. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffares DC, Pain A, Berry A, Cox AV, Stalker J, Ingle CE, Thomas A, Quail MA, Siebenthall K, Uhlemann AC, Kyes S, Krishna S, Newbold C, Dermitzakis ET, Berriman M. Genome variation and evolution of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:120–125. doi: 10.1038/ng1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volkman SK, Sabeti PC, DeCaprio D, Neafsey DE, Schaffner SF, Milner DA Jr, Daily JP, Sarr O, Ndiaye D, Ndir O, Mboup S, Duraisingh MT, Lukens A, Derr A, Stange-Thomann N, Waggoner S, Onofrio R, Ziaugra L, Mauceli E, Gnerre S, Jaffe DB, Zainoun J, Wiegand RC, Birren BW, Hartl DL, Galagan JE, Lander ES, Wirth DF. A genome-wide map of diversity in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:113–119. doi: 10.1038/ng1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlton JM, Escalante AA, Neafsey D, Volkman SK. Comparative evolutionary genomics of human malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidgell C, Volkman SK, Daily J, Borevitz JO, Plouffe D, Zhou Y, Johnson JR, Le Roch K, Sarr O, Ndir O, Mboup S, Batalov S, Wirth DF, Winzeler EA. A systematic map of genetic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e57. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang H, Yi M, Mu J, Zhang L, Ivens A, Klimczak LJ, Huyen Y, Stephens RM, Su XZ. Detection of genome-wide polymorphisms in the AT-rich Plasmodium falciparum genome using a high-density microarray. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:398. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozdech Z, Mok S, Hu G, Imwong M, Jaidee A, Russell B, Ginsburg H, Nosten F, Day NP, White NJ, Carlton JM, Preiser PR. The transcriptome of Plasmodium vivax reveals divergence and diversity of transcriptional regulation in malaria parasites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:16290–16295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807404105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall N, Karras M, Raine JD, Carlton JM, Kooij TW, Berriman M, Florens L, Janssen CS, Pain A, Christophides GK, James K, Rutherford K, Harris B, Harris D, Churcher C, Quail MA, Ormond D, Doggett J, Trueman HE, Mendoza J, Bidwell SL, Rajandream MA, Carucci DJ, Yates JR 3rd, Kafatos FC, Janse CJ, Barrell B, Turner CM, Waters AP, Sinden RE. A comprehensive survey of the Plasmodium life cycle by genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses. Science. 2005;307:82–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1103717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dharia NV, Sidhu AB, Cassera MB, Westenberger SJ, Bopp SE, Eastman RT, Plouffe D, Batalov S, Park DJ, Volkman SK, Wirth DF, Zhou Y, Fidock DA, Winzeler EA. Use of high-density tiling microarrays to identify mutations globally and elucidate mechanisms of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R21. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-2-r21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mu J, Myers RA, Jiang H, Liu S, Ricklefs S, Waisberg M, Chotivanich K, Wilairatana P, Krudsood S, White NJ, Udomsangpetch R, Cui L, Ho M, Ou F, Li H, Song J, Li G, Wang X, Seila S, Sokunthea S, Socheat D, Sturdevant DE, Porcella SF, Fairhurst RM, Wellems TE, Awadalla P, Su XZ. Plasmodium falciparum genome-wide scans for positive selection, recombination hot spots and resistance to antimalarial drugs. Nat. Genet. 2010;42(3):268–71. doi: 10.1038/ng.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mu J, Awadalla P, Duan J, McGee K, Joy D, McVean G, Su X-Z. Recombination hotspots and population structure in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neafsey DE, Schaffner SF, Volkman SK, Park D, Montgomery P, Milner DA Jr, Lukens A, Rosen D, Daniels R, Houde N, Cortese JF, Tyndall E, Gates C, Stange-Thomann N, Sarr O, Ndiaye D, Ndir O, Mboup S, Ferreira MU, Moraes Sdo L, Dash AP, Chitnis CE, Wiegand RC, Hartl DL, Birren BW, Lander ES, Sabeti PC, Wirth DF. Genome-wide SNP genotyping highlights the role of natural selection in Plasmodium falciparum population divergence. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R171. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-12-r171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duan J, Mu J, Thera MA, Joy D, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Diemert D, Long C, Zhou H, Miura K, Ouattara A, Dolo A, Doumbo O, Su XZ, Miller L. Population structure of the genes encoding the polymorphic Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1: Implications for vaccine design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105(22):7857–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802328105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voight BF, Kudaravalli S, Wen X, Pritchard JK. A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e72. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabeti PC, Varilly P, Fry B, Lohmueller J, Hostetter E, Cotsapas C, Xie X, Byrne EH, McCarroll SA, Gaudet R, Schaffner SF, Lander ES. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature. 2007;449:913–918. doi: 10.1038/nature06250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurst LD. Fundamental concepts in genetics: Genetics and the understanding of selection. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10(2):83–93. doi: 10.1038/nrg2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wootton JC, Feng X, Ferdig MT, Cooper RA, Mu J, Baruch DI, Magill AJ, Su XZ. Genetic diversity and chloroquine selective sweeps in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;418:320–323. doi: 10.1038/nature00813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nash D, Nair S, Mayxay M, Newton PN, Guthmann JP, Nosten F, Anderson TJ. Selection strength and hitchhiking around two anti-malarial resistance genes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2005;272:1153–1161. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mu J, Awadalla P, Duan J, McGee KM, Keebler J, Seydel K, McVean GA, Su XZ. Genome-wide variation and identification of vaccine targets in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:126–130. doi: 10.1038/ng1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henrichsen CN, Chaignat E, Reymond A. Copy number variants, diseases and gene expression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:R1–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson TJ, Patel J, Ferdig MT. Gene copy number and malaria biology. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price RN, Uhlemann AC, Brockman A, McGready R, Ashley E, Phaipun L, Patel R, Laing K, Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Nosten F, Krishna S. Mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and increased pfmdr1 gene copy number. Lancet. 2004;364:438–447. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16767-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nair S, Miller B, Barends M, Jaidee A, Patel J, Mayxay M, Newton P, Nosten F, Ferdig MT, Anderson TJ. Adaptive copy number evolution in malaria parasites. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan J, Johnson RL, Huang R, Wichterman J, Jiang H, Hayton K, Fidock DA, Wellems TE, Inglese J, Austin CP, Su XZ. Genetic mapping of targets mediating differential chemical phenotypes in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:765–771. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chakrabarti K, Pearson M, Grate L, Sterne-Weiler T, Deans J, Donohue JP, Ares M Jr. Structural RNAs of known and unknown function identified in malaria parasites by comparative genomics and RNA analysis. RNA. 2007;13:1923–1939. doi: 10.1261/rna.751807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mourier T, Carret C, Kyes S, Christodoulou Z, Gardner PP, Jeffares DC, Pinches R, Barrell B, Berriman M, Griffiths-Jones S, Ivens A, Newbold C, Pain A. Genome-wide discovery and verification of novel structured RNAs in Plasmodium falciparum. Genome Res. 2008;18:281–292. doi: 10.1101/gr.6836108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hertel J, Stadler PF. Hairpins in a Haystack: recognizing microRNA precursors in comparative genomics data. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:e197–202. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iyer J, Gruner AC, Renia L, Snounou G, Preiser PR. Invasion of host cells by malaria parasites: a tale of two protein families. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65:231–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cowman AF, Crabb BS. Invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Cell. 2006;124:755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaur D, Mayer DC, Miller LH. Parasite ligand-host receptor interactions during invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium merozoites. Int. J. Parasitol. 2004;34:1413–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh S, Plassmeyer M, Gaur D, Miller LH. Mononeme: a new secretory organelle in Plasmodium falciparum merozoites identified by localization of rhomboid-1 protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20043–20048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709999104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yeoh S, O'Donnell RA, Koussis K, Dluzewski AR, Ansell KH, Osborne SA, Hackett F, Withers-Martinez C, Mitchell GH, Bannister LH, Bryans JS, Kettleborough CA, Blackman MJ. Subcellular discharge of a serine protease mediates release of invasive malaria parasites from host erythrocytes. Cell. 2007;131:1072–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blackman MJ. Malarial proteases and host cell egress: an 'emerging' cascade. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1925–1934. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balaji S, Babu MM, Iyer LM, Aravind L. Discovery of the principal specific transcription factors of Apicomplexa and their implication for the evolution of the AP2-integrase DNA binding domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3994–4006. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Silva EK, Gehrke AR, Olszewski K, Leon I, Chahal JS, Bulyk ML, Llinas M. Specific DNA-binding by apicomplexan AP2 transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8393–8398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801993105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gajria B, Gao X, Gingle A, Grant G, Harb OS, Heiges M, Innamorato F, Iodice J, Kissinger JC, Kraemer E, Li W, Miller JA, Nayak V, Pennington C, Pinney DF, Roos DS, Ross C, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Treatman C, Wang H. PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D539–543. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Young JA, Johnson JR, Benner C, Yan SF, Chen K, Le Roch KG, Zhou Y, Winzeler EA. In silico discovery of transcription regulatory elements in Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiller NL, Bhattacharjee S, van Ooij C, Liolios K, Harrison T, Lopez-Estrano C, Haldar K. A host-targeting signal in virulence proteins reveals a secretome in malarial infection. Science. 2004;306:1934–1937. doi: 10.1126/science.1102737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marti M, Good RT, Rug M, Knuepfer E, Cowman AF. Targeting malaria virulence and remodeling proteins to the host erythrocyte. Science. 2004;306:1930–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.1102452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maier AG, Rug M, O'Neill MT, Brown M, Chakravorty S, Szestak T, Chesson J, Wu Y, Hughes K, Coppel RL, Newbold C, Beeson JG, Craig A, Crabb BS, Cowman AF. Exported proteins required for virulence and rigidity of Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocytes. Cell. 2008;134:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maier AG, Cooke BM, Cowman AF, Tilley L. Malaria parasite proteins that remodel the host erythrocyte. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:341–354. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Ooij C, Tamez P, Bhattacharjee S, Hiller NL, Harrison T, Liolios K, Kooij T, Ramesar J, Balu B, Adams J, Waters AP, Janse CJ, Haldar K. The malaria secretome: from algorithms to essential function in blood stage infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000084. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Koning-Ward TF, Gilson PR, Boddey JA, Rug M, Smith BJ, Papenfuss AT, Sanders PR, Lundie RJ, Maier AG, Cowman AF, Crabb BS. A newly discovered protein export machine in malaria parasites. Nature. 2009;459:945–949. doi: 10.1038/nature08104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cui L, Fan Q, Miao J. Histone lysine methyltransferases and demethylases in Plasmodium falciparum. Int. J. Parasitol. 2008;38:1083–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cui L, Miao J, Furuya T, Fan Q, Li X, Rathod PK, Su XZ. Histone acetyltransferase inhibitor anacardic acid causes changes in global gene expression during in vitro Plasmodium falciparum development. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:1200–1210. doi: 10.1128/EC.00063-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fan Q, Miao J, Cui L, Cui L. Characterization of protein arginine methyltransferase I from Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. J. 2009;421(1):107–18. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Le Roch KG, Zhou Y, Blair PL, Grainger M, Moch JK, Haynes JD, De La Vega P, Holder AA, Batalov S, Carucci DJ, Winzeler EA. Discovery of gene function by expression profiling of the malaria parasite life cycle. Science. 2003;301:1503–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.1087025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou Y, Young JA, Santrosyan A, Chen K, Yan SF, Winzeler EA. In silico gene function prediction using ontology-based pattern identification. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1237–1245. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou Y, Ramachandran V, Kumar KA, Westenberger S, Refour P, Zhou B, Li F, Young JA, Chen K, Plouffe D, Henson K, Nussenzweig V, Carlton J, Vinetz JM, Duraisingh MT, Winzeler EA. Evidence-based annotation of the malaria parasite's genome using comparative expression profiling. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hu G, Cabrera A, Kono M, Mok S, Chaal BK, Haase S, Engelberg K, Cheemadan S, Spielmann T, Preiser PR, Gilberger TW, Bozdech Z. Transcriptional profiling of growth perturbations of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:91–98. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bozdech Z, Llinas M, Pulliam BL, Wong ED, Zhu J, DeRisi JL. The transcriptome of the intraerythrocytic developmental cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Llinas M, Bozdech Z, Wong ED, Adai AT, DeRisi JL. Comparative whole genome transcriptome analysis of three Plasmodium falciparum strains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1166–1173. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daily JP, Scanfeld D, Pochet N, Le Roch K, Plouffe D, Kamal M, Sarr O, Mboup S, Ndir O, Wypij D, Levasseur K, Thomas E, Tamayo P, Dong C, Zhou Y, Lander ES, Ndiaye D, Wirth D, Winzeler EA, Mesirov JP, Regev A. Distinct physiological states of Plasmodium falciparum in malaria-infected patients. Nature. 2007;450:1091–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature06311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gonzales JM, Patel JJ, Ponmee N, Jiang L, Tan A, Maher SP, Wuchty S, Rathod PK, Ferdig MT. Regulatory hotspots in the malaria parasite genome dictate transcriptional variation. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang Y, Wuchty S, Ferdig MT, Przytycka TM. Graph theoretical approach to study eQTL: a case study of Plasmodium falciparum. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:i15–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lemieux JE, Gomez-Escobar N, Feller A, Carret C, Amambua-Ngwa A, Pinches R, Day F, Kyes SA, Conway DJ, Holmes CC, Newbold CI. Statistical estimation of cell-cycle progression and lineage commitment in Plasmodium falciparum reveals a homogeneous pattern of transcription in ex vivo culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:7559–7564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811829106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jiang H, Patel JJ, Yi M, Mu J, Ding J, Stephens R, Cooper RA, Ferdig MT, Su XZ. Genome-wide compensatory changes accompany drug- selected mutations in the Plasmodium falciparum crt gene. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stubbs J, Simpson KM, Triglia T, Plouffe D, Tonkin CJ, Duraisingh MT, Maier AG, Winzeler EA, Cowman AF. Molecular mechanism for switching of P. falciparum invasion pathways into human erythrocytes. Science. 2005;309:1384–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.1115257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gaur D, Furuya T, Mu J, Jiang LB, Su XZ, Miller LH. Upregulation of expression of the reticulocyte homology gene 4 in the Plasmodium falciparum clone Dd2 is associated with a switch in the erythrocyte invasion pathway. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006;145:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eksi S, Haile Y, Furuya T, Ma L, Su X, Williamson KC. Identification of a subtelomeric gene family expressed during the asexual-sexual stage transition in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2005;143:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Deitsch KW. A mark of silence in malaria parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:112–113. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deitsch KW, Lukehart SA, Stringer JR. Common strategies for antigenic variation by bacterial, fungal and protozoan pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:493–503. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scherf A, Lopez-Rubio JJ, Riviere L. Antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;62:445–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Su XZ, Heatwole VM, Wertheimer SP, Guinet F, Herrfeldt JA, Peterson DS, Ravetch JA, Wellems TE. The large diverse gene family var encodes proteins involved in cytoadherence and antigenic variation of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82:89–100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen Q, Fernandez V, Sundstrom A, Schlichtherle M, Datta S, Hagblom P, Wahlgren M. Developmental selection of var gene expression in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 1998;394:392–395. doi: 10.1038/28660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chookajorn T, Dzikowski R, Frank M, Li F, Jiwani AZ, Hartl DL, Deitsch KW. Epigenetic memory at malaria virulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:899–902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609084103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Duraisingh MT, Voss TS, Marty AJ, Duffy MF, Good RT, Thompson JK, Freitas-Junior LH, Scherf A, Crabb BS, Cowman AF. Heterochromatin silencing and locus repositioning linked to regulation of virulence genes in Plasmodium falciparum. Cell. 2005;121:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Freitas-Junior LH, Hernandez-Rivas R, Ralph SA, Montiel-Condado D, Ruvalcaba-Salazar OK, Rojas-Meza AP, Mancio-Silva L, Leal-Silvestre RJ, Gontijo AM, Shorte S, Scherf A. Telomeric heterochromatin propagation and histone acetylation control mutually exclusive expression of antigenic variation genes in malaria parasites. Cell. 2005;121:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Deitsch KW, Calderwood MS, Wellems TE. Malaria. Cooperative silencing elements in var genes. Nature. 2001;412:875–876. doi: 10.1038/35091146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gannoun-Zaki L, Jost A, Mu J, Deitsch KW, Wellems TE. A silenced Plasmodium falciparum var promoter can be activated in vivo through spontaneous deletion of a silencing element in the intron. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:490–492. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.490-492.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lopez-Rubio JJ, Gontijo AM, Nunes MC, Issar N, Hernandez Rivas R, Scherf A. 5' flanking region of var genes nucleate histone modification patterns linked to phenotypic inheritance of virulence traits in malaria parasites. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;66:1296–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lopez-Rubio JJ, Mancio-Silva L, Scherf A. Genome-wide analysis of heterochromatin associates clonally variant gene regulation with perinuclear repressive centers in malaria parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Salcedo-Amaya AM, van Driel MA, Alako BT, Trelle MB, van den Elzen AM, Cohen AM, Janssen-Megens EM, van de Vegte-Bolmer M, Selzer RR, Iniguez AL, Green RD, Sauerwein RW, Jensen ON, Stunnenberg HG. Dynamic histone H3 epigenome marking during the intraerythrocytic cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:9655–9660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902515106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chaal BK, Gupta AP, Wastuwidyaningtyas BD, Luah YH, Bozdech Z. Histone deacetylases play a major role in the transcriptional regulation of the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000737. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Florens L, Washburn MP, Raine JD, Anthony RM, Grainger M, Haynes JD, Moch JK, Muster N, Sacci JB, Tabb DL, Witney AA, Wolters D, Wu Y, Gardner MJ, Holder AA, Sinden RE, Yates JR, Carucci DJ. A proteomic view of the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle. Nature. 2002;419:520–526. doi: 10.1038/nature01107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lasonder E, Ishihama Y, Andersen JS, Vermunt AM, Pain A, Sauerwein RW, Eling WM, Hall N, Waters AP, Stunnenberg HG, Mann M. Analysis of the Plasmodium falciparum proteome by high-accuracy mass spectrometry. Nature. 2002;419:537–542. doi: 10.1038/nature01111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cooper RA, Carucci DJ. Proteomic approaches to studying drug targets and resistance in Plasmodium. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 2004;4:41–51. doi: 10.2174/1568005043480989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Prieto JH, Koncarevic S, Park SK, Yates J, Becker K. Large-Scale Differential Proteome Analysis in Plasmodium falciparum under Drug Treatment. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e4098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Belli SI, Walker RA, Flowers SA. Global protein expression analysis in apicomplexan parasites: current status. Proteomics. 2005;5:918–924. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lal K, Prieto JH, Bromley E, Sanderson SJ, Yates JR, 3rd Wastling JM, Tomley FM, Sinden RE. Characterisation of Plasmodium invasive organelles; an ookinete microneme proteome. Proteomics. 2009;9(5):1142–51. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tarun AS, Peng X, Dumpit RF, Ogata Y, Silva-Rivera H, Camargo N, Daly TM, Bergman LW, Kappe SH. A combined transcriptome and proteome survey of malaria parasite liver stages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:305–310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710780104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lasonder E, Janse CJ, van Gemert GJ, Mair GR, Vermunt AM, Douradinha BG, van Noort V, Huynen MA, Luty AJ, Kroeze H, Khan SM, Sauerwein RW, Waters AP, Mann M, Stunnenberg HG. Proteomic profiling of Plasmodium sporozoite maturation identifies new proteins essential for parasite development and infectivity. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000195. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Khan SM, Franke-Fayard B, Mair GR, Lasonder E, Janse CJ, Mann M, Waters AP. Proteome analysis of separated male and female gametocytes reveals novel sex-specific Plasmodium biology. Cell. 2005;121:675–687. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Trelle MB, Salcedo-Amaya AM, Cohen AM, Stunnenberg HG, Jensen ON. Global Histone Analysis by Mass Spectrometry Reveals a High Content of Acetylated Lysine Residues in the Malaria Parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8(7):3439–50. doi: 10.1021/pr9000898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Di Girolamo F, Raggi C, Birago C, Pizzi E, Lalle M, Picci L, Pace T, Bachi A, de Jong J, Janse CJ, Waters AP, Sargiacomo M, Ponzi M. Plasmodium lipid rafts contain proteins implicated in vesicular trafficking and signalling as well as members of the PIR superfamily, potentially implicated in host immune system interactions. Proteomics. 2008;8:2500–2513. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Singh M, Mukherjee P, Narayanasamy K, Arora R, Sen SD, Gupta S, Natarajan K, Malhotra P. Proteome analysis of plasmodium falciparum extracellular secretory antigens at asexual blood stages reveals a cohort of proteins with possible roles in immune modulation and signaling. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2009;8(9):2102–18. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900029-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Olszewski KL, Morrisey JM, Wilinski D, Burns JM, Vaidya AB, Rabinowitz JD, Llinas M. Host-parasite interactions revealed by Plasmodium falciparum metabolomics. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tyagi N, Swapna LS, Mohanty S, Agarwal G, Gowri VS, Anamika K, Priya ML, Krishnadev O, Srinivasan N. Evolutionary divergence of Plasmodium falciparum: sequences, protein-protein interactions, pathways and processes. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets. 2009;9:257–271. doi: 10.2174/1871526510909030257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bongfen SE, Laroque A, Berghout J, Gros P. Genetic and genomic analyses of host-pathogen interactions in malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kafsack BF, Llinas M. Eating at the table of another: metabolomics of host-parasite interactions. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Balu B, Shoue DA, Fraser MJ Jr, Adams JH. High-efficiency transformation of Plasmodium falciparum by the lepidopteran transposable element piggyBac. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16391–16396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504679102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Janse CJ, Ramesar J, Waters AP. High-efficiency transfection and drug selection of genetically transformed blood stages of the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:346–356. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]