Abstract

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is a cAMP-activated Cl− channel expressed in the apical membrane of fluid-transporting epithelia. The apical membrane density of CFTR channels is determined, in part, by endocytosis and the postendocytic sorting of CFTR for lysosomal degradation or recycling to the plasma membrane. Although previous studies suggested that ubiquitination plays a role in the postendocytic sorting of CFTR, the specific ubiquitin ligases are unknown. c-Cbl is a multifunctional molecule with ubiquitin ligase activity and a protein adaptor function. c-Cbl co-immunoprecipitated with CFTR in primary differentiated human bronchial epithelial cells and in cultured human airway cells. Small interfering RNA-mediated silencing of c-Cbl increased CFTR expression in the plasma membrane by inhibiting CFTR endocytosis and increased CFTR-mediated Cl− currents. Silencing c-Cbl did not change the expression of the ubiquitinated fraction of plasma membrane CFTR. Moreover, the c-Cbl mutant with impaired ubiquitin ligase activity (FLAG-70Z-Cbl) did not affect the plasma membrane expression or the endocytosis of CFTR. In contrast, the c-Cbl mutant with the truncated C-terminal region (FLAG-Cbl-480), responsible for protein adaptor function, had a dominant interfering effect on the endocytosis and plasma membrane expression of CFTR. Moreover, CFTR and c-Cbl co-localized and co-immunoprecipitated in early endosomes, and silencing c-Cbl reduced the amount of ubiquitinated CFTR in early endosomes. In summary, our data demonstrate that in human airway epithelial cells, c-Cbl regulates CFTR by two mechanisms: first by acting as an adaptor protein and facilitating CFTR endocytosis by a ubiquitin-independent mechanism, and second by ubiquitinating CFTR in early endosomes and thereby facilitating the lysosomal degradation of CFTR.

Keywords: ABC Transporter, E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, Endocytosis, Protein Sorting, Ubiquitination, Lysosomal Degradation

Introduction

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)2 is an ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter and a cAMP-activated Cl− channel that mediates transepithelial Cl− transport in diverse tissues, including the airway (1–3), where CFTR plays a critical role in regulating mucociliary clearance by maintaining the airway surface liquid (4, 5). CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion across polarized epithelial cells is regulated by modulating channel activity and by controlling the number of CFTR channels in the plasma membrane (6, 7). The apical membrane density of CFTR channels depends on the plasma membrane delivery of newly synthesized CFTR and on CFTR trafficking at the plasma membrane (i.e. endocytosis and recycling). CFTR is internalized from the plasma membrane by a clathrin-dependent mechanism into early endosomes (EEs) (i.e. endocytosis), from where it is delivered to lysosomes for degradation or is recycled to the plasma membrane. In human airway epithelial cells, CFTR endocytosis and recycling are rapid processes (i.e. minutes) and are regulated.

Ubiquitination regulates the endocytosis and postendocytic sorting of numerous proteins, including ion channels and transporters (8, 9). Ubiquitination is mediated in three steps by ubiquitin-activating (E1), conjugating (E2), and ligase (E3) enzymes, giving rise to an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal glycine of ubiquitin, a conserved 76-amino acid peptide, and a lysine in the target protein (10). Conjugation of a single ubiquitin is known as monoubiquitination, whereas the formation of a ubiquitin chain is known as polyubiquitination (10, 11). Internalization signals as well as the lysosomal and proteosomal degradation signals are determined by the linkage, topology, and length of the ubiquitin chain on target proteins. Recent studies indicate that the ubiquitin system regulates the postendocytic sorting of CFTR. The addition of ubiquitin to the C terminus of CFTR enhances the lysosomal degradation of CFTR and reduces the plasma membrane expression of CFTR in BHK cells (12). Nedd4-2, an E3 enzyme, ubiquitinates ΔF508-CFTR and inhibits its plasma membrane expression in CFPAC-1 cells (13). However, the pathway of ΔF508-CFTR trafficking regulated by Nedd4-2 is unknown. Deubiquitination, or removal of ubiquitin moieties from endocytosed proteins by deubiquitinating enzymes, regulates postendocytic protein trafficking by facilitating protein recycling to the plasma membrane (14). The deubiquitinating enzyme USP10 increases the plasma membrane expression of CFTR in CFBE41o− cells by deubiquitinating CFTR in EE and thereby directing endocytosed CFTR to the recycling pathway (15).

E3 enzymes recognize and interact with specific target proteins (10). The identity of E3 ligases that regulate endocytosis and the postendocytic sorting of CFTR is unknown despite the evidence that ubiquitination plays a role in these trafficking events. c-Cbl (for casitas B-lineage lymphoma) is a member of the RING (really interesting new gene) finger domain family of ubiquitin ligases (16, 17). This multifunctional protein is also an adaptor protein by virtue of its proline-rich region and C-terminal domain (16, 17). c-Cbl facilitates the endocytosis and lysosomal degradation of proteins that possess a tyrosine kinase domain and/or associate with cytoplasmic protein-tyrosine kinases (17, 18). c-Cbl interacts with proteins at the plasma membrane and facilitates their endocytosis by ubiquitinating the membrane protein and/or by facilitating the assembly of the membrane protein into a macromolecular complex that facilitates endocytosis. Once the c-Cbl-target protein complex is endocytosed, c-Cbl remains associated with the target protein in early and late endosomes, where the target protein may be subjected to multiple rounds of c-Cbl-mediated ubiquitination (19–21). Little is known about the role of c-Cbl in airway cells, and as of this time, c-Cbl has not been reported to regulate the trafficking of ion channels. Hence, a goal of this study was to determine whether c-Cbl regulates the endocytic and postendocytic trafficking of CFTR. We report that in human airway epithelial cells, c-Cbl regulates CFTR by two mechanisms: first by acting as an adaptor protein and facilitating CFTR endocytosis by an ubiquitin-independent mechanism, and second by ubiquitinating CFTR in EE and thereby facilitating the lysosomal degradation of CFTR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

CFBE41o− cells stably expressing wild type CFTR (WT-CFTR) (a generous gift from Dr. J. P. Clancy, University of Alabama at Birmingham) were seeded on Transwell (4.67 or 44 cm2) or Snapwell (1.12 cm2, 0.4-μm pore size; Corning Inc.) permeable supports coated with Vitrogen plating medium (VPM) containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen), human fibronectin (10 μg/ml; BD Biosciences), 1% purified collagen (PureColTM, Inamed (Fremont, CA)), and bovine serum albumin (10 μg/ml; Invitrogen) and maintained as polarized monolayers in air-liquid interface culture as described previously (22, 23). CFBE41o− cells transfected with plasmid DNA were seeded on VPM-coated plastic tissue culture plates (Corning Inc.) and cultured for 48 h. FBS and the selection antibiotic were removed from the media 24 h before experiments to augment cell polarization and cell cycle synchronization (24, 25). Primary differentiated human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells (homozygous WT-CFTR) were isolated from the proximal airways of patients undergoing lung transplant for end stage lung diseases, under a protocol approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, or from organ donor lungs not suitable for human use (provided by the Center for Organ Recovery and Education). HBE cells (pass one) were cultured on human placental collagen-coated Transwell (4.67 cm2, 0.4-μm pore size) permeable supports at a density of ∼2 × 105 cells/cm2 in bronchial epithelial growth medium at air-liquid interface for 4–5 weeks as described previously (26, 27).

RNA-mediated Interference

Transfection of siRNA targeting the human c-cbl gene (si-c-Cbl; Hs_CBL_7_HP validated siRNA, Qiagen (Valencia, CA)) or siRNA control (si-Neg, Qiagen) into CFBE41o− cells was conducted using HiPerFect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A second siRNA, targeting another non-conserved region of the human c-cbl gene purchased from Qiagen (Hs_CBL_8_HP validated siRNA) also silenced the expression of c-Cbl with similar efficiency. The Hs_CBL_7_HP validated siRNA was used in subsequent experiments. Two transfection protocols were used. In initial experiments, CFBE41o− cells (0.1 × 106) were plated on VPM-coated Transwell permeable supports, and 3 days after seeding cells were incubated with the optimized transfection mixture containing a 15 nm concentration of either si-c-Cbl or si-Neg at 37 °C. Transfection medium was removed after 24 h and was replaced with normal growth medium. Cells were cultured for an additional 72 h to form polarized monolayers (total 7 days in culture). si-c-Cbl reduced c-Cbl protein expression by 54.5 ± 4.3% of si-Neg (p < 0.05) as assessed by Western blotting (n = 4 in each group; data not shown). In subsequent experiments, CFBE41o− cells (1.0 × 106) were plated on tissue culture plates and incubated with the optimized transfection mixture containing a 50 nm concentration of either si-c-Cbl or si-Neg at 37 °C. After 24 h, cells were trypsinized and plated on VPM coated Transwell or Snapwell permeable supports and cultured for an additional 6 days to establish polarized monolayers (total 7 days in culture). si-c-Cbl decreased c-Cbl protein expression by 79.3 ± 2.4% of si-Neg (p < 0.05) as assessed by Western blotting (n = 6 in each group), and the second protocol replaced the first one because of improved c-Cbl silencing efficiency. si-c-Cbl did not affect the protein expression of the homologue, Cbl-b, that shares many substrates with c-Cbl (17). In addition, si-c-Cbl did not affect the protein expression of the endocytic adaptors clathrin, the μ2 subunit of adaptor protein complex-2 (AP-2), and Rab5 in either silencing protocol.

Plasmids and Transient Transfection

The cDNAs encoding human full-length c-Cbl (c-Cbl FL), the c-Cbl fragment with impaired ubiquitin ligase activity lacking 17 residues between amino acids 366 and 382 at the beginning of the RING finger domain (70Z-Cbl), and the truncated c-Cbl fragment expressing amino acid residues 1–480 containing the intact RING finger domain but lacking the proline-rich region and the distal C terminus (Cbl-480) were described previously (28, 29). The cDNAs were synthesized by Origene Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD) in pCMV6 vector with the N-terminal FLAG. In addition, the c-Cbl FL was also expressed in pCMV6 vector with the C-terminal FLAG. Upon receipt, constructs were sequence-verified by ABI PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing (Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA)). Transfection of cells with plasmids was performed using FuGENE6 (Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfected CFBE41o− cells were seeded on VPM-coated tissue-coated plates and harvested 48 h later (30).

Antibodies and Reagents

The following mouse anti-human CFTR antibodies were used: C terminus-specific clone 24-1 (R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN)), clone 596 (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Inc. (Chapel Hill, NC)), and clone M3A7 (Millipore (Billerica, MA)). Other antibodies used were mouse anti-EEA1 (early endosomal antigen 1), mouse anti-Rab5, mouse anti-LAMP-1, mouse anti-clathrin heavy chain, and mouse anti-μ2 adaptin (AP50, a subunit of AP-2; BD Biosciences), mouse anti-Na,K-ATPase (Millipore), mouse anti-FLAG M2 and rabbit anti-FLAG F7425 (Sigma), rabbit anti-c-Cbl (C-15), rabbit anti-Cbl-b and goat anti-Cbl-b (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA)), mouse anti-ubiquitin FK2 (detects mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins; Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA)), and horseradish peroxide-conjugated goat anti-mouse, goat anti-rabbit, and rabbit anti-goat secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad). Goat anti-mouse IgG1 coupled to Alexa 647, goat anti-mouse IgG2b coupled to Alexa 546, and goat anti-rabbit coupled to Alexa 488 were purchased from Invitrogen. All antibodies were used at the concentrations recommended by the manufacturer or as indicated in the figure legends.

Biochemical Determination of the Plasma Membrane CFTR

The biochemical determination of plasma membrane CFTR was performed by domain-selective plasma membrane biotinylation in cells grown on permeable growth supports or by cell surface biotinylation in cells grown in tissue culture dishes using EZ-LinkTM sulfosuccinimidyl-6-(biotinamido)hexanoate (Pierce), followed by cell lysis in buffer containing 25 mm HEPES, pH 8.0, 1% Triton, 10% glycerol, 1 mm Na3VO4, and Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science), as described previously in detail (31, 32). Incubation of cells with cycloheximide (20 μg/ml; Sigma), a protein synthesis inhibitor, was performed at 37 °C, and the disappearance of CFTR from the apical plasma membrane was monitored over time, as described previously (23). Biotinylated CFTR was visualized by Western blotting with mouse monoclonal antibodies, clone 596, or the C terminus-specific clone 24-1 and an anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase antibody using the Western LightningTM Plus-ECL detection system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) followed by chemiluminescence. Quantification of biotinylated CFTR was performed by densitometry using exposures within the linear dynamic range of the film.

Endocytic Assay

Endocytic assays were performed in CFBE41o− cells, as described previously (33, 34). Briefly, the plasma membrane proteins were first biotinylated at 4 °C using EZ-LinkTM sulfosuccinimidyl-2-(biotinamido)ethyl-1,3-dithiopropionate (Pierce). Cells were rapidly warmed to 37 °C for 2.5, 5, 7.5, or 10 min after biotinylation, and subsequently, the disulfide bonds on Sulfo-NHS-SS-biotinylated proteins remaining in the plasma membrane were reduced by GSH (Sigma) at 4 °C. At this point in the protocol, biotinylated proteins reside within the endosomal compartment. Subsequently, cells were lysed, and biotinylated proteins were isolated by streptavidin-agarose beads, eluted into SDS-sample buffer, and separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE. The amount of biotinylated CFTR at 4 °C and without the 37 °C warming was considered 100%. The amount of biotinylated CFTR remaining in the plasma membrane after GSH treatment at 4 °C and without the 37 °C warming was considered background (5.6 ± 1.1% compared with the amount of biotinylated CFTR at 4 °C without GSH treatment) and was subtracted from the CFTR biotinylated after warming to 37 °C at each time point. CFTR endocytosis was calculated after subtraction of the background and was expressed as the percentage of biotinylated CFTR at each time point after warming to 37 °C compared with the amount of biotinylated CFTR present before warming to 37 °C.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

CFTR and c-Cbl were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates or from EE fractions by methods described previously (23, 30). Briefly, cultured cells were lysed in an immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer containing 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1% IGEPAL (Sigma), 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 30 mm NaF, 1 mm Na3VO4, 10 mm N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma) to inhibit deubiquitinating enzymes and Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Sciences). After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 min to pellet insoluble material, the soluble lysates were precleared by incubation with protein G or protein A, as appropriate, conjugated to Sepharose beads (Pierce) at 4 °C. The precleared lysates were added to the protein G- or protein A-Sepharose bead antibody complexes. CFTR was immunoprecipitated by incubation with the mouse M3A7 antibody, and c-Cbl was immunoprecipitated by incubation with the rabbit C-15 antibody. Non-immune mouse or rabbit IgGs (DAKO North America, Inc. (Carpinteria, CA)) were used as controls. After washing the protein G- or protein A-Sepharose bead antibody complexes with the IP buffer, immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted by incubation at 85 °C for 5 min in sample buffer (Bio-Rad) containing 80 mm dithiothreitol. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using 7.5 or 15% gels (Bio-Rad) and analyzed by Western blotting. The immunoreactive bands were visualized with the Western LightningTM Plus-ECL detection system.

For immunoprecipitation of the plasma membrane CFTR, apical membrane proteins were first isolated using domain-selective cell surface biotinylation, as described above. Biotin-labeled plasma membrane proteins were eluted from streptavidin beads by incubation with the elution buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.8, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1% SDS, 10 mm dithiothreitol) for 5 min at room temperature and for another 5 min at 85 °C. Eluates were diluted with 10 volumes of dilution buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.8, 10% (v/v) glycerol, Complete protease inhibitor mixture tablet to neutralize dithiothreitol). Diluted eluates were then combined with antibody M3A7-protein G-Sepharose complex beads at 4 °C for 2 h to immunoprecipitate biotinylated (i.e. apical plasma membrane) CFTR. IP samples and cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting as described above.

Density Gradient Separation of Early Endosomes

To isolate the EE fraction, subcellular fractionation was performed using a 5–20% (w/v) continuous OptiPrepTM (Sigma) gradient formed by overlaying a 5% gradient on top of a 20% gradient at room temperature for 4 h. OptiPrepTM and buffer solutions were prepared as described previously (35) and as in the OptiPrepTM Application Sheet (available on the World Wide Web). For ubiquitination studies, CFBE41o− cells were pretreated with 200 μm chloroquine (Sigma) in serum-free culture medium for 5 h at 37 °C to inhibit lysosomal degradation of ubiquitinated CFTR. Cells were then washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline three times and scraped into 0.7 ml of homogenization buffer containing 250 mm sucrose, 78 mm KCl, 4 mm MgCl2, 8.4 mm CaCl2, 10 mm EGTA, 50 mm HEPES-KOH, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate (pH 7.0) and the Complete protease inhibitor mixture and passed through a 22-gauge syringe at a 1-ml maximum volume 30 times. A postnuclear supernatant was generated by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The postnuclear supernatant was placed on the 5–20% continuous OptiPrepTM gradient and centrifuged in a TH-660 rotor (6 × 4.4 ml) in a Sorvall Discovery 90SE Ultracentrifuge at 100,000 × g for 18 h at 4 °C. Fractions were collected and kept at 4 °C for no more than 8 h while an aliquot of each fraction was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis to localize the EE markers, EEA1 and Rab5. LAMP-1 and Na,K-ATPase, not localized to early endosomes, were used as negative controls. The EE fractions were then pooled and subjected to immunoprecipitation assays as described above.

Ussing Chamber Measurements

Ussing chamber measurements were performed as previously described (36). Monolayers of airway cells grown on Snapwell permeable supports were mounted in an Ussing-type chamber (Physiologic Instruments (San Diego, CA)) and bathed in solutions (see below) maintained at 37 °C and stirred by bubbling with 5% CO2, 95% air. Short circuit current (Isc) was measured by voltage-clamping the transepithelial voltage across the monolayers to 0 mV with a voltage/current clamp (model VCC MC8, Physiologic Instruments) as described previously (36). Data collection and analysis were done with the Acquire & Analyze Data Acquisition System (Physiologic Instruments). CFBE41o− cells were bathed in solutions with an apical-to-basolateral Cl− gradient in the presence of amiloride (100 μm) in the apical bath solution to inhibit Na+ absorption. The apical bath solution contained 115 mm sodium gluconate, 5 mm NaCl, 25 mm NaHCO3, 3.3 mm KH2PO4, 0.8 mm K2HPO4, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 4 mm calcium gluconate, 10 mm mannitol (pH 7.4). The basolateral bath solution contained 120 mm NaCl, 25 mm NaHCO3, 3.3 mm KH2PO4, 0.8 mm K2HPO4, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 1.2 mm CaCl2, 10.0 mm glucose (pH 7.4). A low Cl−, high-Na+, high gluconate, apical bath solution was used to prevent cell swelling due to the increased apical Cl− permeability under these conditions, as described previously (36). Isc was stimulated with 20 μm forskolin and 50 μm IBMX added to the apical and basolateral bath solution. Thiazolidinone CFTRinh-172 (20 μm; Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO)) was added to the apical bath solution to inhibit CFTR-mediated Isc. Data are expressed as forskolin/IBMX-stimulated Isc, calculated by subtracting the base-line Isc from the peak stimulated Isc.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy studies were conducted to examine co-localization between c-Cbl and CFTR in early endosomes. CFBE41o− cells were grown on VPM-coated glass coverslips to 60–70% confluence. Cells were first treated for 1 min before fixation with 0.03% saponin in 25 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 25 mm KCl, 2.5 mm magnesium acetate, 5 mm EGTA, and 150 mm potassium glutamate to remove soluble cytosolic proteins, as described previously (37). Subsequently, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 15 min and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and three times with 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.15% glycine in phosphate-buffered saline (PBG buffer), followed by blocking with 20% normal goat serum in PBG buffer for 30 min. The cells were then incubated for 1 h with the primary antibodies anti-EEA1 (mouse monoclonal IgG1), anti-CFTR MAB596 (mouse monoclonal IgG2b), and c-Cbl C-15 (rabbit polyclonal) before incubating in secondary antibodies, which were goat anti-mouse IgG1-Alexa 647 (1:2,000), goat anti-mouse IgG2b-Alexa 546 (1:2,000), and goat anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa-488 (1:500). The coverslips were mounted in Gelvatol (Sigma), and the cells were imaged on an inverted FluoView 1000 confocal microscope (Olympus (Center Valley, PA)) using the ×60, numerical aperture 1.42 oil immersion objective and 2.5 digital zoom. Sequential line scan was used to assure that no signal bleed-through occurred among channels. Controls included secondary antibodies alone as well as primary antibodies alone. The specificity of anti-mouse secondary antibodies was confirmed by lack of cross-reactivity with the primary mouse antibodies IgG1 and IgG2b.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software Inc. (San Diego, CA)). The means were compared by a two-tailed t test. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

CFTR Co-imunoprecipitates with c-Cbl in Human Airway Epithelial Cells

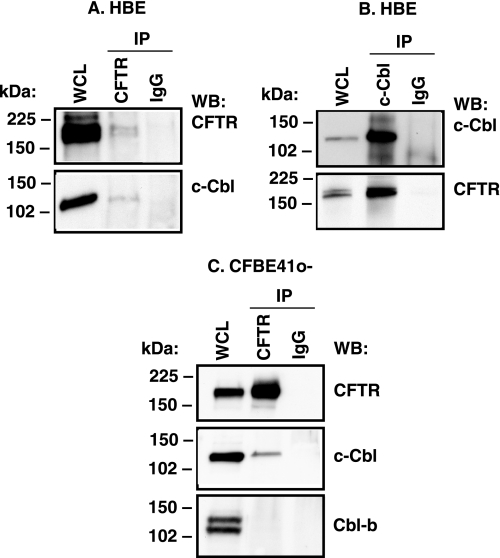

We examined whether c-Cbl interacts with CFTR in primary differentiated HBE cells (homozygous WT-CFTR). CFTR was immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal anti-CFTR antibody (M3A7), and c-Cbl was immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal anti-c-Cbl antibody (C-15) in reciprocal experiments. Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitated protein complexes demonstrated that endogenous c-Cbl and CFTR co-immunoprecipitated in HBE cells (Fig. 1, A and B). Furthermore, CFTR and c-Cbl co-immunoprecipitated in cultured human bronchial epithelial cells (CFBE41o−) stably expressing WT-CFTR (Fig. 1C). By contrast, Cbl-b, a homologue of c-Cbl that shares many c-Cbl substrates, did not co-immunoprecipitate with CFTR (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that endogenous c-Cbl and CFTR interact in human airway epithelial cells.

FIGURE 1.

Representative immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrating the interaction between c-Cbl and CFTR in primary differentiated HBE cells (homozygous WT-CFTR; A and B) and immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells (CFBE41o−, stably expressing WT-CFTR; C). CFTR was immunoprecipitated with antibody M3A7 (IP CFTR), and c-Cbl was immunoprecipitated with antibody C-15 (IP c-Cbl). The homologue of c-Cbl, Cbl-b, was detected with rabbit polyclonal antibody in the whole cell lysate (WCL) of CFBE41o− cells, but it did not co-immunoprecipitate with CFTR. Similar results were obtained using a goat polyclonal anti-Cbl-b antibody (data not shown). Mouse or rabbit non-immune IgGs were used as controls (IP IgG). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using 7.5% gels (2% of the whole cell lysate run on gel). The experiments shown in A and B were performed with HBE from two different sources. All experiments were repeated three times from separate cultures with similar results. WB, Western blot.

c-Cbl Interacts with CFTR in the Plasma Membrane in Human Airway Epithelial Cells

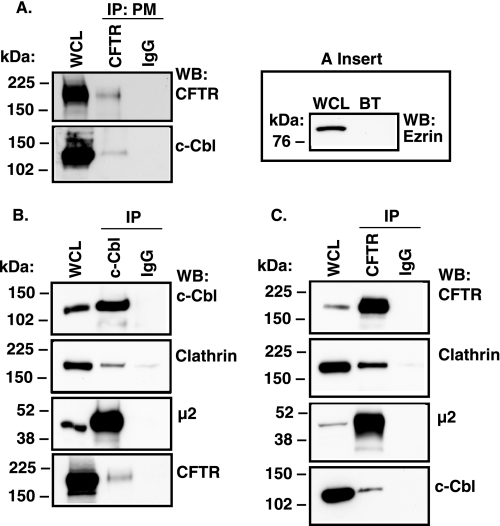

Additional immunoprecipitation experiments were conducted to examine whether c-Cbl interacts with CFTR in the plasma membrane. Apical plasma membrane proteins were selectively biotinylated, isolated by streptavidin beads, eluted from the beads, and incubated with anti-CFTR antibody M3A7. As demonstrated in Fig. 2A, endogenous c-Cbl co-immunoprecipitated with the plasma membrane CFTR. The absence of ezrin, an intracellular protein, in the biotinylated protein complexes indicated that only plasma membrane proteins were biotinylated (Fig. 2A, inset). If c-Cbl plays a role in CFTR endocytosis in human airway epithelial cells, c-Cbl and CFTR should interact with clathrin and the plasma membrane-specific clathrin adaptor complex, AP-2. To test this hypothesis, CFTR and c-Cbl were immunoprecipitated from lysates of polarized CFBE41o− cells using the anti-CFTR and anti-c-Cbl antibody, respectively. Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitated protein complexes demonstrated that clathrin and the μ2 adaptin (a subunit of AP-2) co-immunoprecipitated with c-Cbl and CFTR (Fig. 2, B and C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that CFTR and c-Cbl interact in the apical plasma membrane in human airway epithelial cells.

FIGURE 2.

Immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrating that c-Cbl and CFTR interact in the plasma membrane and that both proteins interact with the plasma membrane endocytic adaptor complex in human airway epithelial cells (CFBE41o−). A, apical plasma membrane proteins were selectively biotinylated and isolated by streptavidin beads, and plasma membrane CFTR was immunoprecipitated (IP: PM CFTR) with antibody M3A7. The absence of ezrin, an intracellular protein, in the biotinylated (BT) protein complexes indicates that only plasma membrane proteins were biotinylated (A, inset). B, c-Cbl was immunoprecipitated from the whole cell lysate (WCL) using antibody C-15 (IP c-Cbl). C, CFTR was immunoprecipitated from the WCL using antibody M3A7 (IP CFTR). Mouse or rabbit non-immune IgGs were used as controls (IP: PM IgG). Clathrin and the μ2 subunit of AP2 co-immunoprecipitated with c-Cbl and CFTR. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using 7.5% gels (2% of the WCL run on gel). All experiments were repeated three times from separate cultures with similar results. WB, Western blot.

Silencing c-Cbl Increases the Plasma Membrane Expression of CFTR in Polarized Human Airway Epithelial Cells

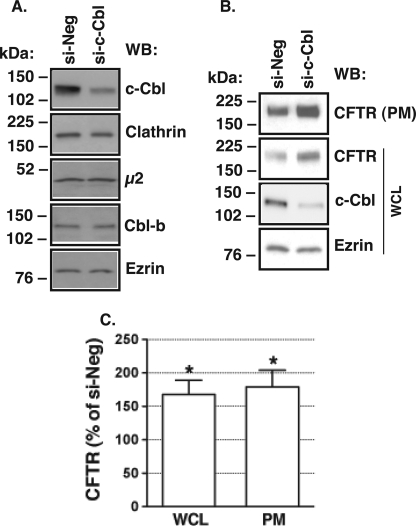

If c-Cbl facilitates CFTR endocytosis, it is predicted that decreased c-Cbl expression would attenuate CFTR endocytosis and thus would increase the plasma membrane expression of CFTR. To test this prediction, c-Cbl expression was reduced in CFBE41o− cells by RNA-mediated interference (siRNA), as described under “Materials and Methods.” CFBE41o− cells were transfected with siRNA specific for a non-conserved region of the human c-Cbl sequence (si-c-Cbl) or with a non-silencing siRNA control (si-Neg). si-c-Cbl decreased the protein abundance of c-Cbl without decreasing the protein abundance of the homologue, Cbl-b, or of the endocytic adaptors, clathrin and μ2 adaptin (Fig. 3A). Silencing c-Cbl increased the steady-state plasma membrane expression of CFTR (Fig. 3, B and C). Furthermore, silencing c-Cbl increased the total cellular expression of CFTR (Fig. 3, B and C).

FIGURE 3.

Silencing experiments performed to determine the effects of c-Cbl on CFTR expression in polarized CFBE41o− cells. Cells were transfected with 15 nm si-c-Cbl as described under “Materials and Methods.” A, representative Western blot experiment demonstrating that si-c-Cbl decreased expression of endogenous c-Cbl in the WCL but did not affect the expression of the homologue, Cbl-b, or the endocytic adaptors, clathrin and the μ2 subunit of AP-2. Shown are a representative Western blot (B) and summary of experiments (C) demonstrating that si-c-Cbl increased CFTR expression in the WCL and in the plasma membrane (PM) at steady state. Plasma membrane proteins were isolated by selective apical membrane biotinylation. Ezrin was used as a loading control. *, p < 0.05 versus control (6 experiments/group). WB, Western blot. Error bars, S.E.

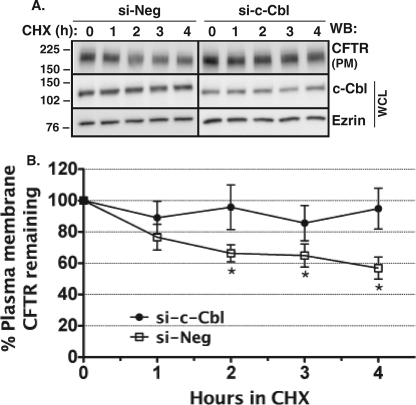

Next, studies were conducted to determine the effect of silencing c-Cbl on CFTR stability in the plasma membrane as a function of time. The disappearance of CFTR from the plasma membrane of CFBE41o− cells after apical plasma membrane biotinylation at 4 °C was monitored over time at 37 °C in the presence of 20 μg/ml cycloheximide, a protein synthesis inhibitor, as described under “Materials and Methods.” As illustrated in Fig. 4, in control experiments (si-Neg), the amount of CFTR in the plasma membrane significantly decreased by 2 h. By contrast, silencing c-Cbl eliminated the decline in the amount of plasma membrane CFTR. Taken together, the data in Figs. 3 and 4 demonstrate that, in polarized human airway epithelial cells, expression of CFTR in the plasma membrane is regulated by c-Cbl.

FIGURE 4.

Biotinylation experiments performed to determine the effects of the siRNA-mediated silencing of c-Cbl on CFTR expression in the plasma membrane of CFBE41o− cells as a function of time. CFBE41o− cells were transfected with 15 nm si-c-Cbl as described under “Materials and Methods.” Disappearance of CFTR from the plasma membrane was monitored over time in the presence of 20 μg/ml cyclohexamide (CHX) at 37 °C. Shown are a representative Western blot (A) and summary of experiments (B) demonstrating that silencing c-Cbl increased CFTR stability in the apical plasma membrane (PM). Plasma membrane proteins were isolated by selective apical membrane biotinylation. Ezrin expression in the WCL was used as the loading control. *, p < 0.05 versus time 0 in si-Neg control. Plasma membrane CFTR in the si-c-Cbl-transfected cells did not change in the 4-h experimental period. 4–5 experiments/group were performed. WB, Western blot. Error bars, S.E.

Silencing c-Cbl Decreases CFTR Endocytosis

Endocytic assays were conducted to determine if si-c-Cbl increased the membrane abundance of CFTR by inhibiting the endocytic removal of CFTR from the apical plasma membrane. The si-Neg control had no effect on CFTR endocytosis as compared with non-transfected polarized CFBE41o− cells (data not shown). As illustrated in Fig. 5, si-c-Cbl decreased CFTR endocytosis. The reduction in CFTR endocytosis is consistent with the increased plasma membrane expression of CFTR observed in cells transfected with si-c-Cbl (Figs. 3 and 4) and demonstrates that c-Cbl facilitates CFTR endocytosis.

FIGURE 5.

Summary of endocytic assays performed to determine the effects of silencing c-Cbl on CFTR endocytosis in CFBE41o− cells. Cells were transected with 15 nm si-c-Cbl as described under “Materials and Methods.” Shown are a representative Western blot (A) and summary of experiments (B) demonstrating that reducing c-Cbl protein expression decreased CFTR endocytosis. The amount of biotinylated CFTR (BT) remaining after the GSH treatment at 4 °C without warming to 37 °C was considered background and was subtracted from the amount of biotinylated CFTR remaining after warming to 37 °C at each time point. CFTR endocytosis was calculated after subtraction of the background (see above) and was expressed as the percentage of CFTR remaining biotinylated before and after warming to 37 °C. CFTR endocytosis was linear up to 7.5 min. Ezrin expression in the WCL was used as a loading control. *, p < 0.05 versus si-Neg (4 experiments/group). WB, Western blot. Error bars, S.E.

Silencing c-Cbl Increases CFTR-mediated Cl− Secretion across Polarized Human Airway Epithelial Cells

CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion is determined by the activity and number of plasma membrane CFTR Cl− channels. Because silencing c-Cbl decreased endocytosis and increased the plasma membrane expression of CFTR, we predicted that it would also increase CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion (34). si-c-Cbl increased the forskolin/IBMX-stimulated Cl− currents across CFBE41o− monolayers (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Ussing chamber experiments performed to determine the effects of silencing c-Cbl expression on the CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion across CFBE41o− monolayers. Cells were transected with 50 nm si-c-Cbl, as described under “Materials and Methods.” Non-transfected cells (Non-trans) were used as an additional control. CFBE41o− cells were bathed in solutions with an apical-to-basolateral Cl− gradient in the presence of amiloride (100 μm) in the apical bath solution to inhibit Na+ absorption through ENaC. Isc was stimulated with forskolin (20 μm) and IBMX (50 μm) added to the apical and basolateral bath solution. Thiazolidonone CFTRinh-172 (20 μm) was added to the apical bath solution to inhibit CFTR-mediated Isc. Data are expressed as net stimulated Isc, calculated by subtracting the base-line Isc from the peak stimulated Isc. Shown are a summary of experiments (A) and representative recordings (B) demonstrating that reducing c-Cbl expression increased the forskolin/IBMX-stimulated Isc across CFBE41o− cells. si-Neg did not affect the forskolin/IBMX-stimulated Isc. *, p < 0.05 versus non-transfected cells and si-Neg. 14 monolayers in the non-transfected group and 28 monolayers in the si-Neg and si-c-Cbl group, each from three different cultures. WB, Western blot. Error bars, S.E.

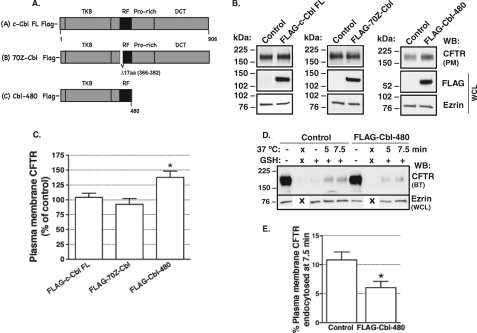

The c-Cbl C-terminal Region Facilitates CFTR Endocytosis

c-Cbl may regulate CFTR endocytosis by the RING finger domain-mediated ubiquitination of CFTR and/or by facilitating the assembly of an endocytic adaptor complex mediated by the proline-rich region and the distal C terminus of c-Cbl (38, 39). To examine the mechanism whereby c-Cbl facilitates CFTR endocytosis, we generated recombinant c-Cbl fragments (Fig. 7A), as described previously (28, 29). Deletion of 17 amino acids at the beginning of the RING finger domain (FLAG-70Z-Cbl) inactivates the ubiquitin ligase function, whereas truncation of the proline-rich region and the distal C terminus beyond amino acid residue 480 (FLAG-Cbl-480) prevents protein-protein interactions mediated by these regions. Overexpression of the full-length c-Cbl with FLAG at the N terminus (FLAG-c-Cbl FL) did not decrease the plasma membrane abundance of CFTR when compared with the vector control (Fig. 7, B and C). Similar results were obtained when the c-Cbl FL was expressed with the C-terminal FLAG (data not shown). These data indicate that the position of FLAG did not change the effect of the recombinant c-Cbl FL on the plasma membrane abundance of CFTR. The lack of the inhibitory effect demonstrates that the endogenous c-Cbl was sufficient to maximally regulate the trafficking of CFTR at the plasma membrane in CFBE41o− cells. If c-Cbl regulates CFTR endocytosis via its ubiquitin ligase activity, the FLAG-70Z-Cbl fragment deficient in ubiquitin ligase activity should compete with and displace the endogenous c-Cbl and thus should inhibit endocytosis and increase CFTR expression in the plasma membrane (dominant interfering effect). However, the FLAG-70Z-Cbl did not increase the plasma membrane expression of CFTR (Fig. 7, B and C); nor did it inhibit CFTR endocytosis (CFTR endocytosis was 10.53 ± 1.3 and 12.98 ± 2.84% at 7.5 min in the FLAG-70Z-Cbl and the control transfected cells, respectively; n = 5 in each group; p = not significant). These data indicate that c-Cbl does not regulate CFTR endocytosis by virtue of its ubiquitin ligase activity.

FIGURE 7.

Biotinylation experiments demonstrating the effects of recombinant c-Cbl fragments on the plasma membrane expression of CFTR in CFBE41o− cells. A, domain map of c-Cbl. A (A), the human c-cbl gene (Gene ID 867) encodes a 906-amino acid full-length protein (44). The TKB domain interacts with target proteins or their adaptors, the RING finger (RF) domain mediates the ubiquitin ligase activity, and the proline-rich (Pro-rich) and the distal C terminus (DCT) recruit numerous endocytic adaptors. A (B), FLAG-70Z-Cbl is a c-Cbl fragment with a deletion of 17 residues between amino acids 366 and 382 in the RING finger domain that leads to impaired ubiquitin ligase activity (17, 45). A (C), FLAG-Cbl-480 is a c-Cbl fragment expressing amino acids 1–480 with a truncation of the entire proline-rich region and the distal C terminus. Shown are representative Western blots (B) and a summary of experiments (C) demonstrating the effects of the FLAG-c-Cbl fragments on the plasma membrane (PM) CFTR expression. B, overexpression of the full-length c-Cbl with FLAG at the N terminus (FLAG-c-Cbl FL; left) did not decrease the plasma membrane abundance of CFTR. Similar results were obtained with the c-Cbl FL expressed with the C-terminal FLAG (data not shown). The FLAG-70Z-Cbl (middle) did not increase the plasma membrane CFTR expression. In contrast, the FLAG-Cbl-480 (right) had a dominant interfering effect and increased expression of CFTR in the plasma membrane. Shown are representative Western blots (D) and a summary of experiments (E) demonstrating that the FLAG-Cbl-480 had a dominant interfering effect and decreased CFTR endocytosis. X, lanes that were not loaded with sample. CFTR endocytosis was linear up to 7.5 min (see Fig. 5), and the data were analyzed at the 7.5 min time point. The pCMV6 FLAG vector was used as a control. Ezrin expression in the WCL was used as a loading control. *, p < 0.05 versus control (5–8 experiments/group in B and C and 5 experiments/group in D and E). Error bars, S.E.

By contrast, if c-Cbl facilitates CFTR endocytosis by acting as a protein adaptor, the FLAG-Cbl-480 mutant should displace endogenous c-Cbl and disrupt the adaptor protein complex containing c-Cbl that is necessary for CFTR endocytosis. The FLAG-Cbl-480 fragment increased CFTR expression in the plasma membrane (Fig. 7, B and C) and decreased CFTR endocytosis (Fig. 7, D and E). Taken together, the data demonstrate that c-Cbl regulates CFTR endocytosis by acting as an adaptor/scaffolding protein and not as a ubiquitin ligase.

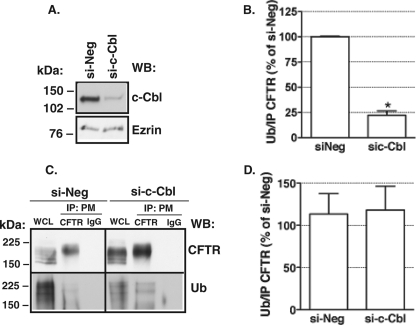

Silencing c-Cbl Does Not Decrease the Abundance of Ubiquitinated CFTR in the Plasma Membrane

Although inactivating the ubiquitin ligase in c-Cbl did not influence CFTR endocytosis, it is formally possible that c-Cbl may ubiquitinate CFTR in the apical plasma membrane but that ubiquitination does not affect CFTR endocytosis. Thus, studies were conducted to examine whether c-Cbl ubiquitinates CFTR in the plasma membrane using the siRNA approach. si-c-Cbl decreased c-Cbl protein expression by 76.7 ± 0.9% (Fig. 8, A and B). Apical membrane proteins were selectively biotinylated and isolated by streptavidin beads and eluted from the beads, and CFTR was immunoprecipitated with antibody M3A7. Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitated plasma membrane protein complex demonstrated, similar to previous experiments (Fig. 3C), that silencing c-Cbl increased the protein abundance of CFTR in the plasma membrane (Fig. 8C). Ubiquitinated CFTR was detected in the immunoprecipitated protein complex in both the control (si-Neg)- and si-c-Cbl-treated cells with the anti-ubiquitin antibody FK2 that recognizes mono- and polyubiquitinated proteins (Fig. 8, C and D). There was more ubiquitinated CFTR in the plasma membrane of si-c-Cbl-treated cells compared with control cells (Fig. 8C); however, the amount of ubiquitinated CFTR relative to the amount of CFTR immunoprecipitated was similar in both groups (Fig. 8D). The observation that a 76% reduction in c-Cbl did not decrease the total or relative amount of ubiquitinated CFTR in the plasma membrane is consistent with the observation that the c-Cbl does not ubiquitinate CFTR in the plasma membrane.

FIGURE 8.

Summary of immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrating that c-Cbl does not ubiquitinate CFTR in the apical plasma membrane. CFBE41o− cells were transfected with 50 nm si-c-Cbl or si-Neg as described under “Materials and Methods.” Shown are a representative Western blot (A) and summary of data (B) demonstrating c-Cbl expression in the WCL in these immunoprecipitation experiments. Ezrin expression in the WCL was used as a loading control. Apical plasma membrane proteins were selectively biotinylated and isolated by streptavidin beads, and CFTR was immunoprecipitated with antibody M3A7 (IP: PM CFTR). Mouse non-immune IgG was used as a control (IP: PM IgG). Antibody 596 was used to detect CFTR, and antibody FK2 was used to detect ubiquitinated CFTR. Shown are a representative Western blot (C) and summary of experiments (D) demonstrating that silencing c-Cbl increased expression of CFTR in the WCL and plasma membrane but did not decrease the abundance of ubiquitinated CFTR (Ub). The ubiquitinated CFTR was calculated by dividing the signal above the 150-kDa molecular standard obtained with the anti-ubiquitin antibody FK2 by the signal obtained in Western blots with the anti-CFTR antibody 596 in samples immunoprecipitated from the plasma membrane with anti-CFTR antibody M3A7. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using 7.5% gels (1% of the WCL run on gel). 3 experiments/group were performed. *, p < 0.05 versus si-Neg. Error bars, S.E.

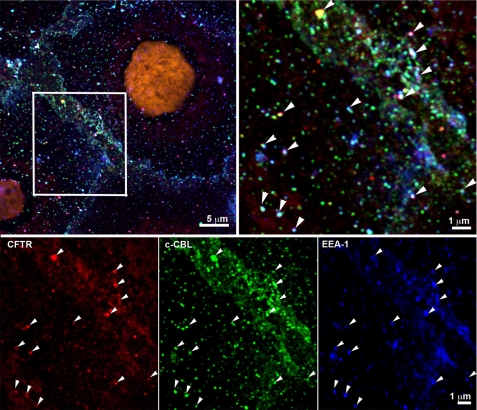

c-Cbl Is Associated with CFTR in Early Endosomes, Where It Ubiquitinates CFTR and Targets Ubiquitinated CFTR for Lysosomal Degradation

Because silencing c-Cbl increased the cellular abundance of CFTR, studies were conducted to test the hypothesis that c-Cbl ubiquitinates CFTR in EE and targets ubiquitinated CFTR for lysosomal degradation. To this end, immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy studies were conducted in CFBE41o− cells to determine if c-Cbl co-localizes with CFTR in EE. Cells were immunolabeled with primary and secondary antibody pairs against CFTR, c-Cbl, and EEA1. As demonstrated in Fig. 9, CFTR and c-Cbl colocalized with EEA1, demonstrating that c-Cbl is associated with CFTR in EE.

FIGURE 9.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy experiments demonstrating that c-Cbl co-localizes with CFTR in EE. Cells were processed and imaged as described under “Materials and Methods.” The arrowheads show colocalization of CFTR (red), c-Cbl (green), and EEA1 (blue) in the merged panel. Each signal is also shown in a single-channel panel to indicate that all three colors are present in the vesicles indicated by the arrowhead. Nuclei were counterstained with 0.1% Hoechst 33258 dye (pseudocolored orange). All experiments were repeated twice from separate cultures with similar results.

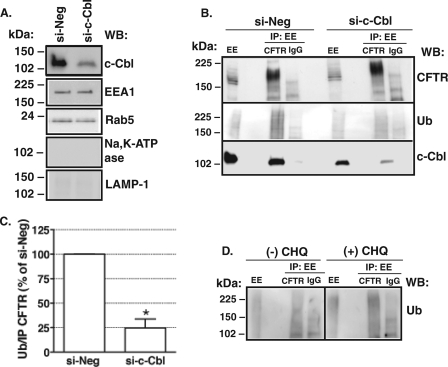

Next, studies were conducted to determine if c-Cbl ubiquitinates CFTR in the EE compartment. Studies were conducted using siRNA-mediated c-Cbl silencing followed by density gradient separation of the EE fraction and immunoprecipitation of CFTR, as described under “Materials and Methods” (Fig. 10A). Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitated protein complexes demonstrated that c-Cbl co-immunoprecipitated with CFTR in EE and that silencing c-Cbl expression decreased the amount of ubiquitinated CFTR and increased the accumulation of CFTR in EE (Fig. 10, B and C).

FIGURE 10.

Summary of immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrating that c-Cbl ubiquitinates CFTR in EE. CFBE41o− cells were transfected with 15 nm si-c-Cbl or si-Neg (A–C), and the EE fraction was isolated as described under “Materials and Methods.” CFTR was immunoprecipitated from the EE fraction with antibody M3A7 (IP CFTR). Mouse non-immune IgG was used as a control (IP: EE IgG). Antibody 596 was used to detect CFTR, and antibody FK2 was used to detect ubiquitinated CFTR. Shown is a representative Western blot (A) demonstrating that si-c-Cbl decreased the EE expression of c-Cbl and did not affect the expression of Rab5 or EEA1. As expected, Na,K-ATPase (a marker of the plasma membrane) and LAMP1 (a lysosomal marker) were absent from the EE fraction. Shown are a representative Western blot (B) and summary of experiments (C) demonstrating that silencing c-Cbl decreased the abundance of ubiquitinated (Ub) CFTR. D, representative Western blot demonstrating accumulation of ubiquitinated CFTR in the EE fraction isolated from CFBE41o− cells treated with the lysosomal inhibitor, chloroquine (CHQ). The ubiquitinated CFTR was calculated by dividing the signal above the 150-kDa molecular standard obtained with the anti-ubiquitin antibody FK2 by the signal obtained in Western blots with the anti-CFTR antibody 596 in samples immunoprecipitated from the EE fraction with anti-CFTR antibody M3A7. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using 7.5 or 15% gels (2% of the EE fraction run on gel). *, p < 0.05 versus si-Neg (3 experiments/group). Error bars, S.E.

To determine if ubiquitinated CFTR is targeted from EE to lysosomes for degradation, we examined the effect of the lysosomal inhibitor chloroquine on the EE abundance of ubiquitinated CFTR. As demonstrated in Fig. 10D, chloroquine increased the amount of ubiquitinated CFTR in EE. Taken together, these data indicate that c-Cbl is associated with CFTR in EE, where it ubiquitinates CFTR and targets the ubiquitinated CFTR for lysosomal degradation. These data explain our observations described above that silencing endogenous c-Cbl increased the cellular expression of CFTR (Fig. 3C), most likely by inhibiting CFTR ubiquitination in EE and degradation in the lysosome.

DISCUSSION

The major new observation in the present study is that in human airway epithelial cells, c-Cbl regulates CFTR trafficking by two mechanisms: first by functioning as a adaptor protein that facilitates CFTR endocytosis by a ubiquitin independent mechanism, and second by ubiquitinating CFTR in EE and thereby facilitating the lysosomal degradation of CFTR. This is the first report of c-Cbl regulating the trafficking of an ion channel.

Several lines of evidence support the conclusion that c-Cbl facilitates CFTR endocytosis in polarized human airway epithelial cells in a ubiquitin ligase-independent manner. First, si-c-Cbl did not decrease the amount of ubiquitinated CFTR in the plasma membrane, and second, transfection of the c-Cbl mutant lacking ubiquitin ligase activity (FLAG-70Z-Cbl) did not inhibit CFTR endocytosis. Third, the FLAG-Cbl-480 mutant lacking the entire distal C-terminal region of c-Cbl increased the plasma membrane CFTR by reducing CFTR endocytosis. Fourth, CFTR, c-Cbl, clathrin, and the μ2 adaptin co-immunoprecipitated in human airway epithelial cells. Several studies have demonstrated that c-Cbl is a multifunctional adaptor protein that facilitates the endocytic retrieval of plasma membrane receptors (16, 17). For example, c-Cbl recruits adaptor proteins, which activate signaling cascades important during receptor endocytosis (40). Taken together, our results support the view that c-Cbl is an adaptor protein in human airway epithelial cells that facilitates CFTR endocytosis.

Several lines of evidence in the present study demonstrated that c-Cbl ubiquitinates CFTR in EE. First, c-Cbl co-immunoprecipitated and co-localized with CFTR in EE. Second, silencing c-Cbl decreased the amount of ubiquitinated CFTR in EE and increased the total cellular expression of CFTR by reducing the amount of ubiquitinated CFTR that is degraded in the lysosome. Taken together, our studies support the view that c-Cbl associates first with the plasma membrane CFTR, where it facilitates CFTR endocytosis by a ubiquitin-independent mechanism, and that c-Cbl ubiquitinates CFTR in EE from where CFTR is targeted for degradation in the lysosome. Although a similar role of c-Cbl was previously shown for EGFR, there are no published data demonstrating c-Cbl regulation of ion channel trafficking (19, 20).

The cellular effects of c-Cbl are regulated by complex network of interactions (41). For example, Nedd4, the HECT type E3 enzyme, binds to two non-overlapping regions of c-Cbl in vitro, and in vivo, it targets c-Cbl for proteosomal degradation, thereby reversing the c-Cbl mediated down-regulation of EGFR (42). We speculate that the dominant interfering effect of the FLAG-Cbl-480 mutant on CFTR endocytosis was accelerated by reduced degradation of the c-Cbl mutant due to its impaired binding to Nedd4. A recent study demonstrated that a protein highly homologous to Nedd4, Nedd4-2, ubiquitinates ΔF508-CFTR and inhibits the plasma membrane expression of ΔF508-CFTR in human airway epithelial cells (13).

It is unknown how c-Cbl interacts with CFTR. The tyrosine kinase-binding (TKB) domain of c-Cbl interacts directly with the tyrosine kinase domain of membrane proteins or indirectly via a cytoplasmic protein-tyrosine kinase (17, 18). CFTR does not have the TKB consensus recognition sequence (NXpY(S/T)XXP, where pY represents phosphotyrosine) present in EGFR and other receptor tyrosine kinases (17). However, binding of the TKB domain by other proteins, such as the Met receptor, occurs through distinct sequences different from those present in receptor tyrosine kinases (43). Future studies are required to determine whether CFTR contains a novel TKB recognition motif or whether the interaction between c-Cbl and CFTR is mediated via a cytoplasmic protein-tyrosine kinase or another regulatory protein targeted directly by c-Cbl.

In summary, our data demonstrate that in human airway epithelial cells, c-Cbl regulates CFTR by two mechanisms: first by acting as an adaptor protein and facilitating CFTR endocytosis by a ubiquitin-independent mechanism, and second by ubiquitinating CFTR in EEs and thereby facilitating the lysosomal degradation of CFTR.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Wakefield (Tranzyme, Inc. (Birmingham, AL)), who generated the CFBE41o− cells stably expressing the WT-CFTR, and Dr. J. P. Clancy (University of Alabama at Birmingham) for providing the stable CFBE41o− cells. We also thank Dr. Allan M. Weissman (Regulation of Protein Function Laboratory, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD)) for valuable comments during preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01HL090767 (to A. S.-U.), R01-DK/HL-45881 (to B. A. S.), R01-DK34533 (to B. A. S.), P20-RR018787 from the National Center for Research Resources (to B. A. S.), and P30-DK072506 (to J. M. P.). This work was also supported by Research Development Program grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (to J. M. P. and B. A. S.).

- CFTR

- cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- WT-CFTR

- wild type CFTR

- VPM

- Vitrogen plating medium

- HBE

- human bronchial epithelial

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- c-Cbl FL

- full-length c-Cbl

- EE

- early endosome

- IBMX

- isobutylmethylxanthine

- WCL

- whole cell lysate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Riordan J. R., Rommens J. M., Kerem B., Alon N., Rozmahel R., Grzelczak Z., Zielenski J., Lok S., Plavsic N., Chou J. L. (1989) Science 245, 1066–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rommens J. M., Iannuzzi M. C., Kerem B., Drumm M. L., Melmer G., Dean M., Rozmahel R., Cole J. L., Kennedy D., Hidaka N. (1989) Science 245, 1059–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard M., Jiang X., Stolz D. B., Hill W. G., Johnson J. A., Watkins S. C., Frizzell R. A., Bruton C. M., Robbins P. D., Weisz O. A. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C375–C382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucher R. C. (2004) Eur. Respir. J. 23, 146–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarran R., Button B., Boucher R. C. (2006) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 68, 543–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertrand C. A., Frizzell R. A. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 285, C1–C18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guggino W. B., Stanton B. A. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 426–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H., Traub L. M., Weixel K. M., Hawryluk M. J., Shah N., Edinger R. S., Perry C. J., Kester L., Butterworth M. B., Peters K. W., Kleyman T. R., Frizzell R. A., Johnson J. P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14129–14135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin D. H., Sterling H., Wang Z., Babilonia E., Yang B., Dong K., Hebert S. C., Giebisch G., Wang W. H. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 4306–4311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pickart C. M. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 503–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hicke L., Dunn R. (2003) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 141–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma M., Pampinella F., Nemes C., Benharouga M., So J., Du K., Bache K. G., Papsin B., Zerangue N., Stenmark H., Lukacs G. L. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 164, 923–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caohuy H., Jozwik C., Pollard H. B. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25241–25253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amerik A. Y., Hochstrasser M. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1695, 189–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bomberger J. M., Barnaby R. L., Stanton B. A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 18778–18789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang X., Sorkin A. (2003) Traffic 4, 529–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thien C. B., Langdon W. Y. (2005) Biochem. J. 391, 153–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dikic I., Szymkiewicz I., Soubeyran P. (2003) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 60, 1805–1827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levkowitz G., Waterman H., Zamir E., Kam Z., Oved S., Langdon W. Y., Beguinot L., Geiger B., Yarden Y. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 3663–3674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Melker A. A., van der Horst G., Calafat J., Jansen H., Borst J. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 2167–2178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dikic I. (2003) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 1178–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bebok Z., Collawn J. F., Wakefield J., Parker W., Li Y., Varga K., Sorscher E. J., Clancy J. P. (2005) J. Physiol. 569, 601–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swiatecka-Urban A., Brown A., Moreau-Marquis S., Renuka J., Coutermarsh B., Barnaby R., Karlson K. H., Flotte T. R., Fukuda M., Langford G. M., Stanton B. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36762–36772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang C., Wang X., Caldwell R. B. (1997) J. Neurochem. 69, 859–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kues W. A., Anger M., Carnwath J. W., Paul D., Motlik J., Niemann H. (2000) Biol. Reprod. 62, 412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devor D. C., Bridges R. J., Pilewski J. M. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C461–C479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myerburg M. M., Latoche J. D., McKenna E. E., Stabile L. P., Siegfried J. S., Feghali-Bostwick C. A., Pilewski J. M. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 292, L1352–L1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galisteo M. L., Dikic I., Batzer A. G., Langdon W. Y., Schlessinger J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 20242–20245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scaife R. M., Langdon W. Y. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swiatecka-Urban A., Boyd C., Coutermarsh B., Karlson K. H., Barnaby R., Aschenbrenner L., Langford G. M., Hasson T., Stanton B. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38025–38031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moyer B. D., Loffing J., Schwiebert E. M., Loffing-Cueni D., Halpin P. A., Karlson K. H., Ismailov I. I., Guggino W. B., Langford G. M., Stanton B. A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21759–22168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swiatecka-Urban A., Duhaime M., Coutermarsh B., Karlson K. H., Collawn J., Milewski M., Cutting G. R., Guggino W. B., Langford G., Stanton B. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40099–40105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watts C., Davidson H. W. (1988) EMBO J. 7, 1937–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swiatecka-Urban A., Talebian L., Kanno E., Moreau-Marquis S., Coutermarsh B., Hansen K., Karlson K. H., Barnaby R., Cheney R. E., Langford G. M., Fukuda M., Stanton B. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 23725–23736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheff D. R., Daro E. A., Hull M., Mellman I. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 145, 123–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swiatecka-Urban A., Moreau-Marquis S., Maceachran D. P., Connolly J. P., Stanton C. R., Su J. R., Barnaby R., O'toole G. A., Stanton B. A. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290, C862–C872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris S. M., Arden S. D., Roberts R. C., Kendrick-Jones J., Cooper J. A., Luzio J. P., Buss F. (2002) Traffic 3, 331–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soubeyran P., Kowanetz K., Szymkiewicz I., Langdon W. Y., Dikic I. (2002) Nature 416, 183–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petrelli A., Gilestro G. F., Lanzardo S., Comoglio P. M., Migone N., Giordano S. (2002) Nature 416, 187–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt M. H., Dikic I. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 907–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan P. E., Davies G. C., Nau M. M., Lipkowitz S. (2006) Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magnifico A., Ettenberg S., Yang C., Mariano J., Tiwari S., Fang S., Lipkowitz S., Weissman A. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 43169–43177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peschard P., Ishiyama N., Lin T., Lipkowitz S., Park M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29565–29571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blake T. J., Shapiro M., Morse H. C., 3rd, Langdon W. Y. (1991) Oncogene 6, 653–657 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Melker A. A., van der Horst G., Borst J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55465–55473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]