Abstract

The antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein is overexpressed in a variety of cancers, particularly leukemias. In some cell types this is the result of enhanced stability of bcl-2 mRNA, which is controlled by elements in its 3′-untranslated region. Nucleolin is one of the proteins that binds to bcl-2 mRNA, thereby increasing its half-life. Here, we examined the site on the bcl-2 3′-untranslated region that is bound by nucleolin as well as the protein binding domains important for bcl-2 mRNA recognition. RNase footprinting and RNA fragment binding assays demonstrated that nucleolin binds to a 40-nucleotide region at the 5′ end of the 136-nucleotide bcl-2 AU-rich element (AREbcl-2). The first two RNA binding domains of nucleolin were sufficient for high affinity binding to AREbcl-2. In RNA decay assays, AREbcl-2 transcripts were protected from exosomal decay by the addition of nucleolin. AUF1 has been shown to recruit the exosome to mRNAs. When MV-4-11 cell extracts were immunodepleted of AUF1, the rate of decay of AREbcl-2 transcripts was reduced, indicating that nucleolin and AUF1 have opposing roles in bcl-2 mRNA turnover. When the function of nucleolin in MV-4-11 cells was impaired by treatment with the nucleolin-targeting aptamer AS1411, association of AUF1 with bcl-2 mRNA was increased. This suggests that the degradation of bcl-2 mRNA induced by AS1411 results from both interference with nucleolin protection of bcl-2 mRNA and recruitment of the exosome by AUF1. Based on our findings, we propose a model that illustrates the opposing roles of nucleolin and AUF1 in regulating bcl-2 mRNA stability.

Keywords: Gene Regulation, Leukemia, RNA-binding Protein, RNA-Protein Interaction, RNA Turnover, AUF1, bcl-2 Oncogene, Exosome, Nucleolin

Introduction

Bcl-2, the prototype for its family, is an antiapoptotic protein. Its overexpression has been implicated in multiple cancers and associated with resistance to chemotherapy, making it an important prognostic factor, particularly in hematological malignancies. The Bcl-2 protein is often highly expressed in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL),5 even though there is no evidence of gene rearrangements that are known to up-regulate bcl-2 transcription. Recently, Otake et al. (1) reported that Bcl-2 overexpression in CLL is related to bcl-2 mRNA stabilization.

It is becoming increasingly clear that mRNA stability is an important control point in the regulation of gene expression. In mammalian cells, regulation of mRNA turnover can dramatically alter the abundance of a particular mRNA without changes in transcription. One of the best characterized regulatory elements present in the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of mRNAs is the AU-rich element (ARE) (for a review, see Ref. 2). These elements are usually composed of AUUUA sequences embedded in a U-rich stretch, and they act as potent mRNA-destabilizing sequences, targeting mRNAs for rapid decay. The bcl-2 mRNA contains an ARE in the 3′-UTR that plays a role in regulating its stability (3, 4). The AREbcl-2 is a sequence of 136 nucleotides (nucleotides 921–1057) just downstream from the stop codon, containing two AUUUA pentamers and a UUAUUUAUU nonamer, which has also been shown to destabilize some mRNAs (4).

Several RNA-binding proteins have been shown to bind to AREs and regulate the fate of the target mRNA. Some of them have multiple functions, but for the most part HuR (5) has been described as an mRNA stabilizer; AUF1 (6), tristetraprolin (7) and K homology splicing regulatory protein (8) as mRNA destabilizers; and TIA-1 (9) and TIAR (10) as translational repressors. Previously, we identified nucleolin as a stabilizer of bcl-2 mRNA in HL60 leukemia cells (11). Nucleolin binds specifically to the 3′-UTR, and it protects AREbcl-2 transcripts from decay in cell-free extracts (11). Otake et al. (1) subsequently found that stabilization of bcl-2 mRNA is, in part, the result of overexpression of nucleolin in the cytoplasm of CLL cells compared with normal CD19+ B cells. Also, Soundararajan et al. (12) have found that nucleolin and Bcl-2 proteins are highly expressed in the cytoplasm of MCF7 breast cancer cells but are not in nonmalignant MCF10A cells.

Nucleolin, also known as C23, is highly conserved among eukaryotes and is ubiquitously expressed. Despite being the most abundant protein in the nucleolus, it shuttles to the cytoplasm, where it participates in mRNA regulation, and it is also found in the plasma membrane (13, 14). As a result, our current view of nucleolin is of a multifunctional protein involved in numerous cellular processes, such as proliferation and growth, transcription, cytokinesis, nucleogenesis, signal transduction, mRNA regulation, apoptosis, induction of chromatin condensation, and replication, to name a few (for a review, see Ref. 15).

The unusual diversity in the biological functions of nucleolin can be understood, at least partially, from its complex protein structure. Nucleolin contains three structural domains: the N-terminal which contains highly acidic residues and a nuclear localization signal; the central domain which contains four ribonucleoprotein-type RNA binding domains (RBDs) that are determinants of RNA-binding specificity; and the C-terminal domain which contains arginine-glycine-glycine repeats (RGGs), participates in interactions with ribosomal proteins (16), exhibits helicase activity (17), and contributes to nonspecific RNA binding (17).

The presence of four RBDs in nucleolin may account for the diversity of target RNAs that are bound by this protein. Nucleolin binds to two different RNA motifs in preribosomal RNA (pre-rRNA), the nucleolin recognition element (NRE) (18, 19) and the evolutionary conserved motif (ECM) (20). None of the four RBDs of nucleolin binds individually to fragments of pre-rRNA; however, a polypeptide containing the first two RBDs binds specifically to a short RNA containing the 18-nucleotide NRE (21). In contrast, binding to RNA containing the 11-nucleotide ECM requires all four RBDs (22). Thus, different combinations of RBDs are used in binding to NRE and ECM RNAs.

In addition to its interactions with pre-rRNA, cytoplasmic nucleolin has been demonstrated to increase (11, 23–28) or decrease (29) the stability of several mRNAs. It also has been shown to stimulate the translation of an mRNA (30). Although the contributions of the RBDs to binding to NRE and ECM RNAs is known, the contributions of the RBDs to binding of specific mRNAs are not known. In addition, the binding site of nucleolin on bcl-2 mRNA has not been mapped. To address these questions, the role of the four RBDs in binding of nucleolin to bcl-2 mRNA was assessed, and the binding site of nucleolin on the AREbcl-2 was mapped.

In mammalian cells, ARE-mediated mRNA decay starts with deadenylation of the 3′ poly(A) tail, followed by 3′-5′ exonucleolytic degradation by a complex of enzymes termed the exosome (for review, see Ref. 31). Mechanistically, ARE motifs are thought to be bound by specific ARE-binding proteins that physically interact with and recruit the RNA decay machinery to the mRNA (8, 31, 32). Studies by Lapucci et al. (33) have suggested that AUF1 plays a role in the turnover of bcl-2 mRNA. In this report we examined the ability of nucleolin to protect bcl-2 mRNA from exosome degradation and tested the hypothesis that nucleolin may compete with AUF1 for binding to bcl-2 mRNA. Based on our findings, we propose a model for how bcl-2 mRNA levels are regulated in normal cells and how, in some cancer cells, aberrant stabilization by nucleolin leads to up-regulation of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

MV-4-11 leukemia cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Cellgro), supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biolabs), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. AS1411 (34) was obtained from Antisoma Research, Ltd. Cells were grown in the presence of additional media or 10 μm AS1411 for 72 h.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Nucleolin

Recombinant pET21a plasmid carrying a truncated nucleolin gene encoding residues 284–710 and six histidines was a gift from Dr. France Carrier (University of Maryland) (35). Recombinant nucleolin with the N-terminal deletion (referred to as Nuc-His) was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). Purification of Nuc-His was performed according to Sengupta et al. (11). Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE, and protein concentration was measured by Bradford assays. GST-nucleolin (containing residues 284–710) was kindly provided by Dr. France Carrier.

Plasmids for expression of fusion proteins containing the maltose-binding protein (MBP) and nucleolin RNA binding domains were a gift from Dr. Nancy Maizels (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) (36). Plasmids pMal-Nuc1,2-RGG and pMal-Nuc3,4-RGG were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells, and expression of proteins was induced by isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. MBP-Nuc fusion proteins were purified as described by Hanakahi et al. (36).

RNase Footprinting

RNA transcripts were prepared by in vitro transcription from plasmid pCR4-ARE using T7 RNA polymerase, as described previously (4). Transcripts were 5′ end-labeled using polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. 200,000 cpm of 32P-ARE RNA were incubated with 0, 50 or 100 nm recombinant Nuc-His in RNA-binding buffer (4) in a final volume of 10 μl for 10 min on ice. Following incubation, reaction mixtures were treated with RNase T1 (final concentration 1 unit/ml) for 10 min at room temperature. After RNase digestion, the reaction was stopped by addition of an equal volume of formaldehyde gel loading buffer. Samples were heated at 95 °C for 5 min and electrophoresed on a 6% polyacrylamide TBE-7 m urea gel. Following electrophoresis, gels were fixed in a 10% acetic acid solution. Gels were dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging. Decade markers (Ambion Inc.) were radiolabeled according to he manufacturer's instructions and used for molecular mass markers.

Preparation of RNA Transcripts

AREbcl-2 and β-globin RNA transcripts were synthesized using T7 RNA polymerase from SpeI-linearized plasmids pCR4-ARE-1A and pCR4-globin, respectively (4). Mutants of AREbcl-2 were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. All-transcripts were synthesized and labeled with [32P]UTP following the manufacturer's protocol of each of the following kits: for noncapped transcripts, MAXIscript T7 kit (Ambion); for capped transcripts, mMessage mMachine T7 kit (Ambion). The purity of RNA transcripts was monitored by analysis on 6% polyacrylamide-8 m urea gel.

Preparation of HeLa Cell S10 and S100 Extracts

Preparation of S100 cytoplasmic extracts was performed following the protocol from Sokoloski et al. (37) with some modifications. Briefly, HeLa cells were centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min, and cell pellets were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Pellets were suspended in buffer A (10 mm HEPES (pH 8.0), 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 0.5 mm PMSF, 0.1% protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 mm DTT). After incubation on ice for 10 min, the suspension was centrifuged. The swollen cell pellet was resuspended in buffer A, lysed with a homogenizer, and centrifuged. The supernatant was collected, supplemented with buffer B (]300 mm HEPES (pH 8.0), 30 mm MgCl2, 1.4 m KCl), and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and stored immediately at −80 °C. Protein concentration was established by Bradford assay. Independent extracts were standardized by assessment of poly(A) ribonuclease levels as described by Sokoloski et al. (37).

For S10 cytoplasmic extracts, HeLa cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in hypotonic buffer (20 mm HEPES (pH 8.0), 10 mm KCl, 0.5 mm DTT, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mm PMSF, 0.1% protease inhibitor mixture, 10 mm benzamide, 20 mm sodium fluoride and 20 mm β-glycerophosphate) and incubated at 4 °C for 15 min. Suspensions were centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations in the extracts were determined by Bradford assays.

RNA Gel Mobility Shift Assays and Determination of Binding Affinities

Gel shift assays were performed as described previously (4, 38). Briefly, [32P]AREbcl-2 transcripts were incubated with recombinant proteins on ice for 10 min and then subjected to electrophoresis on a 1% agarose-TAE gel. Gels were dried on nitrocellulose paper and analyzed by phosphorimaging.

Phosphorimages of gel shift assays were analyzed using ImageQuant software. Curve fitting (nonlinear regression) was performed with Prism 4 software (GraphPad) using the following equation:

where Bmax is the maximum binding and Kd is the concentration of ligand required to reach half-maximum binding. Values reported are the mean ± the range of the extremes (R.E.) or standard error (S.E.).

RNA Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation of protein·RNA complexes was performed as described by Tenenbaum et al. (39) with some modifications. Briefly, S10 extracts were prepared from MV-4-11 cells as described above for HeLa cells. An aliquot of cell lysate (1 mg of total protein) was precleared with protein A/G-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Equal aliquots of the precleared supernatant were incubated with protein A/G-agarose beads that had been preincubated with IgG, polyclonal anti-nucleolin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), monoclonal anti-HuR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or polyclonal anti-AUF1 (Upstate). The agarose beads were washed six times with NT2 buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, and 0.05% Nonidet P-40) and then recovered by centrifugation. RNA was extracted with TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) and treated with RNase-free DNase (Ambion). The purified RNA was used as a template to synthesize cDNA using random hexamer primers and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Fisher) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with SYBR Green mix (Quanta Biosciences) using primers specific for bcl-2 mRNA: forward 5′-CTGGTGGGAGCTTGCATCAC-3′ and reverse 5′-ACAGCCTGCAGCTTTGTTTC-3′; and for GAPDH: forward-5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′ and reverse-5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′.

In Vitro mRNA Decay Assays

To assay for exosome-mediated decay 5′-capped, 32P-labeled transcripts were prepared as described above. RNA transcripts were extracted with TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) and analyzed for purity on denaturing gels before use. Decay assays were performed following the protocol described previously (40, 41). Briefly, 32P-labeled transcripts (2 pmol) were incubated with purified recombinant Nuc-GST protein (100 nm) or with GST (100 nm), followed by addition of 50–60 μg of S100 extracts. Reactions (final volume of 70 μl) were incubated at 30 °C. Aliquots were removed at 0, 30, 60, and 90 min, added to stop buffer, and immediately extracted with TRI Reagent. Recovered RNA was analyzed on 8% polyacrylamide gels containing 8 m urea. After electrophoresis, gels were dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging.

For assays with AUF1-depleted S100 extracts, S100 extracts were incubated with polyclonal anti-AUF1 (Upstate) and protein A/G-agarose beads for 16 h at 4 °C. Suspensions were centrifuged, and the supernatant was subjected to Western blot analysis with monoclonal anti-GAPDH (Chemicon) and polyclonal anti-AUF1 antibodies.

To derive mRNA half-lives, densitometry of phosphorimages was performed using ImageQuant. Prism 4 software (GraphPad) was used to generate nonlinear regression curve fitting with the following equation:

where Y = % RNA remaining; X = time. Y starts at Span+Plateau and decays to Plateau with a rate constant K. The half-life is 0.69/K. Values reported are the means ± S.E.

UV-cross-linking Assays

32P-Labeled AREbcl-2 transcripts were incubated with S10 cytoplasmic extracts of MV-4-11 cells. Complexes were UV-cross-linked (Spectroline) for 20 min at 254 nm. Following UV-cross-linking, samples were digested with RNase A and RNase T1 at 37 °C for 2 h. Extracts were incubated with IgG, anti-nucleolin, or anti-AUF1 antibodies, followed by protein A/G-agarose beads. Beads were washed with cold PBS, and proteins were analyzed on a 10% polyacrylamide-SDS gel. Protein bands containing cross-linked RNA were identified by phosphorimaging of the dried gels.

RESULTS

Identification of the Nucleolin Binding Site on AREbcl-2 RNA

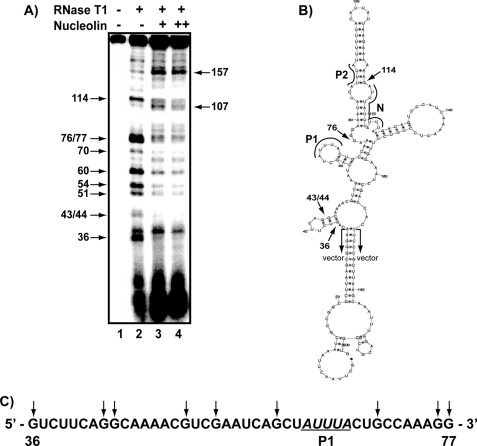

To determine the nucleolin binding site on AREbcl-2, an RNase footprinting assay was performed. 5′-32P-Labeled AREbcl-2 transcripts were synthesized in vitro and subjected to partial digestion with RNase T1, which cleaves after guanine nucleotides. Digestions were performed in the presence or absence of recombinant Nuc-His, which contains amino acid residues 284–710 (35). The resulting RNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on denaturing polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by phosphorimaging. As shown in Fig. 1A, addition of nucleolin to the 203-nucleotide AREbcl-2 transcript (containing the 136-nucleotide ARE and 67 nucleotides of flanking vector sequence) resulted in decreased cleavage of nucleotides G36, G43/44, G51, G54, G60, G70, G76, G77, and G114. Cleavages at nucleotides 107 and 157 appear to be enhanced in the presence of nucleolin (lanes 3 and 4). However, normalization of the bands in each lane on the gel indicated that the increased intensities are due to differences in the amount of loaded material in these lanes.

FIGURE 1.

RNase footprint assay of nucleolin binding site on bcl-2 ARE RNA. A, 5′-[32P]ARE transcripts subjected to partial digestion with RNase T1 in the absence or presence of Nuc-His, as indicated. +, 50 nm nucleolin; ++, 100 nm nucleolin. Fragments were separated on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel and detected by phosphorimaging. Arrows on the left indicate cleavage sites protected by nucleolin; arrows on the right indicate cleavage sites that remained unchanged in the presence of nucleolin. B, potential secondary structure of the AREbcl-2 predicted by M-Fold (56). Arrows indicate the location of the protected cleavage sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the protected region. Regions corresponding to Pentamer 1 (P1), Pentamer 2 (P2), Nonamer (N) as well as the vector sequences are defined. C, sequence of nucleotides 36–77 of AREbcl-2. Residues that were protected by nucleolin from cleavage are indicated by the arrows.

Fig. 1B shows the predicted minimum free energy secondary structure of the AREbcl-2 transcript, where the arrows indicate the cleavage sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the region that was protected from RNase T1 digestion by nucleolin binding (excluding G114; see “Discussion”). This analysis suggests that the primary nucleolin binding site in AREbcl-2 (Fig. 1C) spans a region from one short stem-loop (nucleotides 36–45) to a second stem and loop (nucleotides 58–70) on the left side of the predicted folded structure.

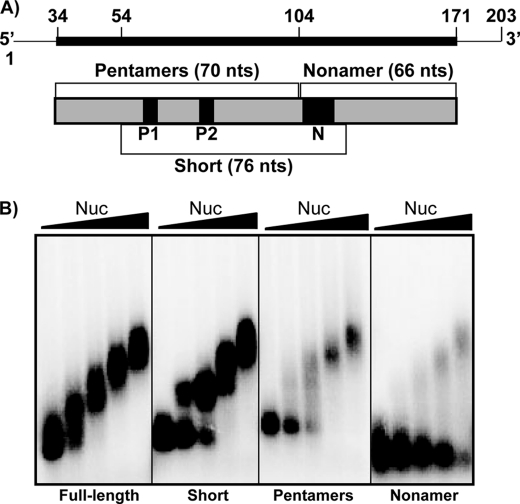

To examine the site of nucleolin binding on AREbcl-2 RNA further, transcripts containing the 5′ or 3′ half of the AREbcl-2 or a region spanning the center of the ARE were synthesized. As noted above, the AREbcl-2 contains two AUUUA pentamers (P1 and P2 in Figs. 1B and 2A), which are located in the 5′ half, and an UUAUUUAUU nonamer (N in Figs. 1B and 2A), which is present in the 3′ half of the ARE. Binding of purified recombinant Nuc-His to the three transcripts was examined by gel shift assays and compared with the affinity for full-length AREbcl-2. As shown in Fig. 2B, nucleolin exhibited strong affinity for the full-length AREbcl-2 (Kd = 88 ± 33 nm (R.E.)), and multiple nucleolin molecules were bound to the RNA at high protein concentrations. Previous studies demonstrated that this binding is specific (11). In contrast, nucleolin bound the nonamer-containing transcript (3′ half of the ARE) with ∼5-fold weaker affinity (Kd = 408 ± 25 nm (R.E.)). The affinities of nucleolin for the Short fragment (Kd = 77 ± 16 nm (R.E.)) and the Pentamer fragment (Kd = 129 ± 26 nm (R.E.)) were similar to that for the full-length ARE.

FIGURE 2.

Binding of nucleolin to fragments of AREbcl-2 RNA. A, schematic representation of the transcripts utilized in binding assays. Transcripts contained the full-length (136 nucleotides) AREbcl-2 or portions containing the two pentamers (P1 and P2) (70 nucleotides), one nonamer (N) (66 nucleotides), or both the pentamers and the nonamer (76 nucleotides = short). Thin line indicates vector sequences present in all transcripts; thick line or boxes indicate bcl-2 mRNA sequences. B, 32P-ARE transcripts (25 nm) incubated in buffer alone or with purified recombinant Nuc-His (50, 100, 200, or 400 nm indicated by triangle above gel). The transcript used in each assay is indicated below the gel. Samples were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel, which was dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging.

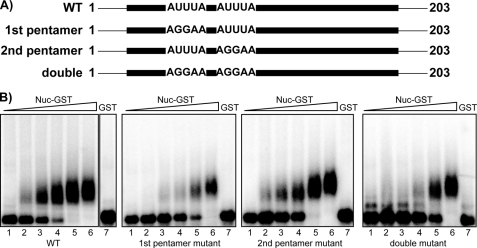

The sequence common to the Short and Pentamer fragments contains nucleotides 50–100. This region overlaps much of the sequence that was protected by nucleolin in the RNase footprint assay (Fig. 1) but lacks nucleotides 36–49 of the RNase-protected sequence. Nucleotides 50–100 contain the two AUUUA pentamers (P1 and P2) that are associated with ARE instability elements in mRNAs. To determine whether either of these sequences is important for nucleolin recognition of AREbcl-2, mutations converting the AUUUA pentamer to AGGAA were introduced into each of the pentamers within the full-length ARE transcript. In addition, a mutant transcript was constructed in which both pentamers were mutated to AGGAA. Binding affinities of GST-nucleolin for the mutant transcripts were measured by gel shift assays (Fig. 3). Mutation of Pentamer 1 increased the Kd of GST-Nuc for the AREbcl-2 transcript by a factor of 2.4 (i.e. from 162 ± 46 nm to 396 ± 127 nm (S.E.)). Mutation of Pentamer 2 had a similar effect, increasing the Kd by a factor of 2 (to 317 ± 93 nm (S.E.)). Interestingly, the mutation of both pentamers did not have an increased effect but rather had a result similar to the individual mutations, changing the Kd by a factor of 2.2 (to 367 ± 142 nm (S.E.)).

FIGURE 3.

Binding of nucleolin to bcl-2-ARE mutant RNAs. A, Schematic representation of the AREbcl-2 mutant transcripts utilized in this experiment. Transcripts contained mutations in the first, second, or in both ARE pentamers present in the AREbcl-2. B, wild-type or mutant [32P]ARE transcripts (25 nm) incubated in buffer alone (lane 1) or with purified recombinant Nuc-GST (50, 100, 200, 400 or 800 nm; lanes 2-6). Lane 7 corresponds to transcripts incubated with 800 nm GST. The transcript used in each assay is indicated below the gel. Samples were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel, which was dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging.

Taken together, these data suggest that the primary binding site(s) for nucleolin is between nucleotides 36 and 77 of the ARE. It seems unlikely that nucleolin binding involves recognition of any one specific AUUUA sequence (e.g. Pentamer 1) because mutation of either one of the two pentamers had a modest effect, and mutation of both pentamers did not enhance this effect.

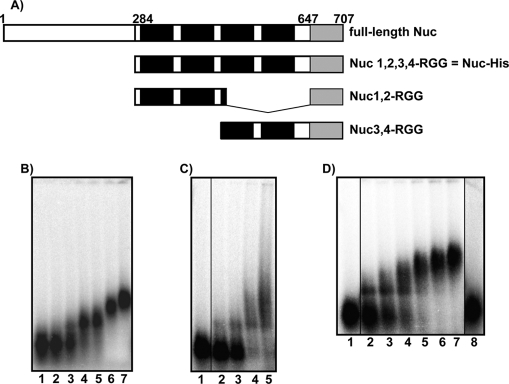

AREbcl-2 Binding Domains of Nucleolin

As noted above, binding of nucleolin to the NRE of pre-rRNA requires only RBDs 1 and 2, whereas binding to ECM RNA requires all four RBDs. Structural studies of the complex of RBD 1,2 and NRE RNA showed that RBDs 1 and 2 bind on opposite sides of the stem and loop structure of NRE RNA (42). Residues in the linker connecting RBDs 1 and 2 contribute to RNA affinity through interactions with the loop and by tethering the two RBDs to RNA. Thus, RBDs 1 and 2 work as a specific pair in binding NRE RNA. In the case of ECM, binding may require two pairs of RBDs (22). To determine whether nucleolin binding to bcl-2 mRNA is similar to binding to NRE or ECM RNA, truncated forms of nucleolin fused with MBP were purified. Polypeptides containing MBP-and nucleolin RBDs 1 and 2 and the RGG domain (Nuc1,2-RGG) or RBD 3 and 4 and the RGG (Nuc3,4-RGG) domain (shown schematically in Fig. 4A) (36) were expressed in E. coli and purified. The RNA binding activities of the polypeptides were compared with the activity of Nuc-His (nucleolin containing RBDs 1,2,3,4-RGG) using gel mobility shift assays (note: MBP-Nuc RBD1,2,3,4-RGG was not soluble and could not be used for these assays). These assays demonstrated that the affinity of MBP-Nuc1,2-RGG for AREbcl-2 (Kd = 63 ± 10 nm (R.E.)) is similar to that of Nuc-His (Kd = 88 nm) (Fig. 4, B and C). Thus, deletion of RBDs 3 and 4 did not detectably diminish the affinity of nucleolin for AREbcl-2. Nuc3,4-RGG also retained the ability to bind to AREbcl-2 (Fig. 4D). However, the affinity of Nuc3,4-RGG for AREbcl-2 (Kd = 194 ± 34 nm (R.E.)) was 3-fold weaker than that of Nuc1,2-RGG. Previous studies by Serin et al. (21) have demonstrated that deletion of the RGG peptide does not significantly affect the affinity of nucleolin for specific RNA but does reduce the affinity for nonspecific RNA. The finding that deletion of RBDs 3 and 4 from Nuc 1,2,3,4-RGG does not diminish the affinity of nucleolin for AREbcl-2 suggests that much of the free energy of bcl-2 RNA binding comes from contributions of RBDs 1 and 2.

FIGURE 4.

Determination of the RNA binding domains required for binding of nucleolin to AREbcl-2 RNA. A, schematic diagram of nucleolin polypeptides used in this study (see “Experimental Procedures”). B–D, gel shift assays of nucleolin polypeptides binding to full-length AREbcl-2 RNA. [32P]RNA was incubated with various protein concentrations, and free and bound RNAs were separated on a native agarose gel. B, AREbcl-2 RNA was incubated with 0, 50, 100, 150, 300, 500, or 750 nm Nuc 1,2,3,4-RGG-His. C, AREbcl-2 RNA incubated with 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100 nm MBP-Nuc 1,2-RGG. Lane 1 is a noncontiguous lane from the same gel. D, binding of MBP-Nuc 3,4-RGG to AREbcl-2 RNA. Lane 1, RNA plus buffer, lanes 2–7, RNA plus 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, and 350 nm MBP-Nuc 3,4-RGG, respectively; lane 8, RNA plus 150 nm MBP. Lanes 1 and 8 are noncontiguous lanes from the same gel.

Nucleolin Inhibits Exosome Degradation in Vitro

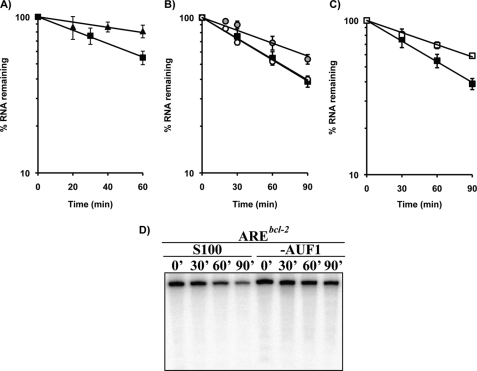

Previous results from our laboratory showed that nucleolin protects 5′-capped, polyadenylated AREbcl-2 transcripts from degradation in cell-free RNA decay assays (11). However, the mechanism of this protection was not examined. AREs stimulate exosomal degradation of mRNAs, but not deadenylation (41, 43). This suggests that nucleolin binding to the ARE region may inhibit exosome-mediated degradation of the mRNA. To test this, the effect of recombinant nucleolin on the decay of 5′-capped AREbcl-2 transcripts lacking a poly(A) tail was examined. First, 32P-labeled transcripts with or without an ARE were incubated with S100 HeLa extracts for up to 1 h, with aliquots being collected every 20 min. Recovered RNA was analyzed on a denaturing gel. As seen in Fig. 5A, capped AREbcl-2 RNA underwent faster degradation (half-life of 67 ± 7 min (S.E.)) than capped, non-ARE containing β-globin transcripts (half-life of 177 ± 22 min (S.E.)), which is in accordance with the ARE being bound by RNA-binding proteins that recruit the exosome (43). Next, reactions were performed in which capped AREbcl-2 transcripts were incubated in HeLa extracts alone or in extracts supplemented with recombinant GST-nucleolin or GST polypeptide. In extracts supplemented with recombinant nucleolin the decay of AREbcl-2 transcripts was prolonged (Fig. 5B; half-life of 99 ± 12 min (S.E.)), indicating that nucleolin protects AREbcl-2 RNA against exosome-mediated degradation. Addition of GST polypeptide to cell extracts had no significant effect on the decay of the transcript (Fig. 5B; half-life of 65 ± 4 min (S.E.)).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of nucleolin and AUF1 on the exosomal degradation of AREbcl-2 transcripts in HeLa extracts. A, 5′-capped [32P]AREbcl-2 (filled squares) and β-globin (filled triangles) transcripts were incubated in S100 HeLa cell extracts, and aliquots were removed at the times indicated. Recovery of RNA was assessed by electrophoresis on denaturing polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by phosphorimaging. Data are represented as a semilog plot of fraction of RNA remaining versus time of incubation in cell extracts. B, recombinant GST-nucleolin was incubated with AREbcl-2 prior to exposure to S100 extracts (gray circles). Filled squares correspond to decay in unsupplemented S100 extracts, and open circles to S100 supplemented with GST. Error bars for open circles are smaller than the symbol. C, AREbcl-2 transcripts were incubated in untreated S100 HeLa extracts (filled squares) or in S100 extracts pretreated with anti-AUF1 antibody (open squares). D, representative gel is shown in which AREbcl-2 transcripts were incubated in untreated S100 HeLa extracts or in AUF1-depleted extracts. Error bars for A–C indicate average of two to four experiments.

Previous studies have suggested that AUF1 plays a role in regulating the stability of bcl-2 mRNA, particularly in response to UVC irradiation (33). AUF1 has been found to interact with the exosome (43) and is thought to destabilize ARE mRNAs by recruiting the exosome to the mRNA. To test the participation of AUF1 in bcl-2 mRNA decay, HeLa cell S100 cytoplasmic extracts were depleted of AUF1 by incubation with anti-AUF1 antibody followed by precipitation with protein A/G-agarose beads. This resulted in ≥50% reduction in the level of AUF1 in S100 extracts of HeLa cells (supplemental Fig. 1). The rate of decay of capped AREbcl-2 transcripts in the depleted extract was then compared with the decay in untreated extracts. Even though there was only partial depletion of AUF1 in the S100 extracts, there was a notable decrease in the rate of decay of AREbcl-2 transcripts (half-life = 118 ± 13 min (S.E.)) compared with untreated extracts (half-life = 67 min) (Figs. and 4D and 5C).

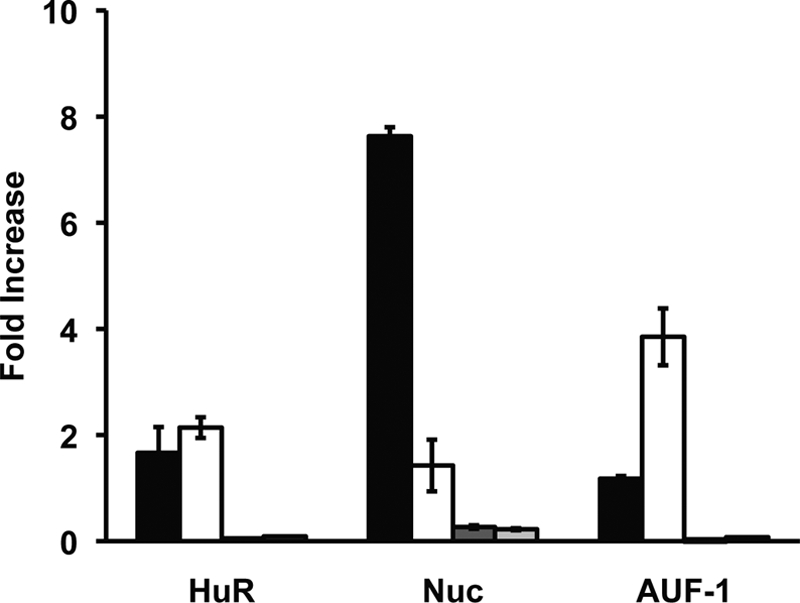

Inhibition of Nucleolin Increases the Interaction of AUF1 with bcl-2 mRNA in Vivo

The above exosome decay assays demonstrated opposing activities of nucleolin and AUF1 with regard to bcl-2 RNA decay. This suggests that nucleolin may stabilize bcl-2 mRNA in vivo by preventing binding of AUF1 to the AREbcl-2, which presumably would reduce access of the exosome to the mRNA. However, the slower decay observed with AUF1-immunodepleted extracts could be due to immunodepletion of exosomal proteins because AUF1 has been shown to co-immunoprecipitate with the exosome (43). To confirm that AUF1 binds to bcl-2 mRNA and to examine whether nucleolin stabilizes the bcl-2 mRNA by preventing AUF1 binding, we treated MV-4-11 cells with the G-rich DNA aptamer AS1411 (34, 44), which has been shown to bind to nucleolin in the plasma membrane (13) and cytoplasm (34). Because AS1411 binds nucleolin with high affinity (45), it is thought to act as a molecular decoy that competes with bcl-2 mRNA for binding to nucleolin. This is supported by the finding that treatment of MV-4-11 cells with AS1411 leads to decreased bcl-2 mRNA stability (12). Accordingly, cells were grown in the presence of AS1411 for 72 h to functionally inhibit nucleolin (12) and then assayed for changes in AUF1, nucleolin, and HuR bound to bcl-2 mRNA. Fig. 6 shows the amount of bcl-2 mRNA immunoprecipitated with anti-AUF1, anti-nucleolin, and anti-HuR antibodies in cytoplasmic extracts of control as well as of cells treated with AS1411. In untreated cells, a 7.6-fold increase of bcl-2 mRNA was recovered with anti-nucleolin antibody compared with IgG antibody, whereas lower amounts bcl-2 mRNA were recovered with anti-HuR (1.7-fold increase) and anti-AUF1 antibodies (1.2-fold increase). Importantly, in AS1411-treated cells a considerable reduction of nucleolin protein bound to bcl-2 mRNA was observed (down to 1.4-fold increase), which occurred in parallel with an enhanced binding of AUF1 (up to 3.8-fold increase). HuR levels bound to bcl-2 mRNA did not change significantly in this time frame. GAPDH mRNA was utilized to monitor for equal sample input. These results indicate that in the absence of active cytoplasmic nucleolin, bcl-2 mRNA is destabilized (12), and increased levels of AUF1 are bound to the mRNA.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of AS1411 on bcl-2 mRNA·AREBP complexes. Cytoplasmic extracts of control or AS1411-treated MV-4–11 cells were incubated with IgG, anti-nucleolin, anti-HuR, or anti-AUF1 antibodies. RNA·protein·antibody complexes were recovered by incubation with protein A/G-agarose beads, and the presence of bcl-2 mRNA in immunoprecipitated complexes was detected by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. Values are the fold increase of bcl-2 mRNA recovered by the indicated antibody over that recovered with IgG antibody. Black bars are bcl-2 mRNA values from untreated MV-4-11 cells; white bars are AS1411-treated cells. Dark gray bars are GAPDH mRNA values from untreated MV-411 cells; light gray bars are AS1411-treated cells. Column heights represent the mean, and error bars show the range of values from two independent experiments.

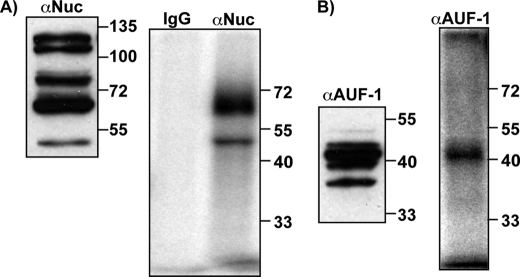

Fragments of Nucleolin and a Specific Isoform of AUF1 Bind the bcl-2 mRNA

In the cell, nucleolin can be found as a full-length protein and/or as several fragments that result from autoproteolysis (46). It is generally considered that in nondividing cells nucleolin is highly phosphorylated and undergoes autoproteolysis, whereas in proliferating cells, full-length, nonphosphorylated nucleolin is favored. However, both full-length nucleolin as well as fragments have been shown to bind RNAs efficiently (11, 23, 29, 35). Additionally, the AUF1 family consists of four isoforms (37, 40, 42, and 45 kDa) generated by alternative pre-mRNA splicing. All of them have been shown to bind RNA, but with different affinities (47). This raises the question of which fragments and isoforms of the two proteins may be involved in binding and regulating bcl-2 mRNA. To address this question, UV-cross-linking assays were performed to investigate which nucleolin fragments and AUF1 isoforms bind bcl-2 mRNA in MV-4-11 cells (Fig. 7). MV-4-11 cytoplasmic extracts were incubated with 32P-labeled AREbcl-2 transcripts and then UV-cross-linked. After RNase treatment, proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-nucleolin, anti-AUFI, or IgG antibodies. Recovered proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by phosphorimaging. In parallel, untreated cytoplasmic extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were detected by Western blotting. Fig. 7A shows that nucleolin is present as five fragments in MV-4-11 cells (left panel). Interestingly, only two fragments (∼50 and 65 kDa) are observed to bind to AREbcl-2 (right panel), but not the full-length protein. Likewise, even though all four isoforms of AUF1 were found in MV-4-11 cytoplasmic extracts (Fig. 7B, left panel), only the 42 kDa is detected after UV-cross-linking to AREbcl-2 (Fig. 7B, right panel).

FIGURE 7.

Detection of nucleolin and AUF1 in MV-4-11 extracts and in UV-cross-linked immunoprecipitants. A, left panel, cytoplasmic extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting. Proteins were detected with anti-nucleolin antibody. A, right panel, cytoplasmic extracts were incubated with [32P]AREbcl-2 transcripts, exposed to UV light, and then digested with RNase. Immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-nucleolin antibody. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was dried and analyzed by phosphorimaging. B, left panel, same as described for A, except that proteins were detected with anti-AUF1 antibody. B, right panel, Same as described for A, except that immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-AUF1 antibody.

DISCUSSION

The RNase footprinting and gel shift RNA binding assays demonstrated that nucleolin binds to an ∼40-nucleotide binding site spanning nucleotides 36–77 at the 5′ end of the AREbcl-2. Gel shift binding assays (Fig. 2) showed that at increasing nucleolin protein concentrations, more than one nucleolin can bind to the AREbcl-2. Thus, the protected region of ∼40 nucleotides may result from binding of two or more nucleolin molecules. RNase protection of G114, which is outside of the primary binding site, may arise from G114 being spatially close to the 40-nucleotide sequence in the three-dimensional folded structure of the RNA. Alternatively, nucleolin binding could be inducing a conformational change in the transcript that results in G114 becoming susceptible to T1 cleavage and thus, G114 may not be in the nucleolin binding site.

Mutation analysis further showed that the AUUUA pentamers and the nonamer (UUAUUUAUU) sequence likely do not contribute significantly to the nucleolin binding energy. Thus, nucleolin does not appear to recognize typical ARE motifs in bcl-2 mRNA. Comparison of the sequence of the defined bcl-2 binding region with the NRE (18, 19) and ECM (20) binding sites shows little similarity. Nucleolin binding sites on amyloid precursor protein (29), interleukin-2 (26), and CD154 (23) mRNAs have been mapped, and although these mRNAs do not contain ARE motifs, there is a CU-rich sequence (CUCUCUUUC/AC) that is common to the three mRNAs. This sequence is not present in the bcl-2 ARE. Thus, it appears that nucleolin recognizes a different sequence within bcl-2 mRNA from other mRNAs. Also, it is likely that secondary and tertiary structures are important for nucleolin recognition because the binding site is a relatively large region containing potential stem and loop secondary structures. The finding that nucleolin binding to the ARE likely involves RBDs 1 and 2 suggests that the mode of binding may be similar to the interaction of nucleolin with the NRE, in which nucleolin binds to a stem and loop structure (48).

The nucleolin binding site defined here is upstream from the site on the AREbcl-2 that is bound by HuR which overlaps the nonamer sequence (Fig. 2) (49). This finding is consistent with the results reported by Ishimaru et al. (2009) which showed that the two proteins can bind concurrently to AREbcl-2 RNA in vitro. This supports the idea that nucleolin and HuR are present in common bcl-2 messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes involved in regulating the stability and translation of bcl-2 mRNA (49). ARE motifs facilitate rapid turnover of mRNAs and normally help to block inappropriate accumulation of the proteins they encode (50). Selective control of ARE mRNAs comes from the fact that ARE sequences are unique and are bound by specific ARE-binding factors, including stabilizing as well as destabilizing factors. Thus, the stability of an mRNA depends on the repertoire of RNA-binding proteins present in a particular cell under specific conditions. A number of studies have shown that abnormal control of mRNA stability can contribute to the development and/or maintenance of malignancies (for review, see Ref. 51).

The short half-life of ARE-containing mRNAs has been related to recruitment of the exosome by ARE-binding proteins, such as AUF1 (6, 43). Lapucci et al. (33) demonstrated that AUF1 is involved in bcl-2 mRNA decay during apoptosis, specifically in response of Jurkat cells to UVC irradiation. Interestingly, when AUF1 was depleted from MV-4-11 S100 extracts, the rate of decay of bcl-2 mRNA was reduced (Fig. 5). Moreover, when nucleolin function was impaired by treatment of MV-4-11 cells with the aptamer AS1411, increased binding of AUF1 to bcl-2 mRNA was observed (Fig. 6) in the same time frame when lower bcl-2 mRNA levels have been detected (12), suggesting that nucleolin and AUF1 have opposing roles in the regulation of the bcl-2 mRNA stability. Even though our results suggest that AUF1 has a prominent role in stimulating bcl-2 mRNA degradation when nucleolin levels are low (Fig. 6), at this time one cannot rule out the possibility that both proteins could be present on the same bcl-2 mRNA molecule simultaneously, as has been shown with HuR and p37/AUF1 (52). Also, it is likely that other proteins, in addition to AUF1, play a role in the turnover of bcl-2 mRNA in some cells. For example, it was recently reported that Bcl-2 protein itself plays a role in regulating the decay of its cognate mRNA (53). Other RNA cis-elements can also contribute to bcl-2 mRNA regulation. Specifically, Lee et al. (54) demonstrated that CA repeats upstream of the ARE confer bcl-2 mRNA instability in the absence of an apoptotic stimulus in COS7 cells.

The AUF1 family consists of four splicing isoforms: the 45 kDa, which contains all exons; 42 kDa, which lacks exon 2; 40 kDa, which lacks exon 7; and 37 kDa, with both exons 2 and 7 deleted. The four isoforms have been described to differ in their ARE-binding affinities in vitro, with p37 having the highest affinity, followed by p42, p45, and finally by p40 (47). The effects of each isoform individually or in combination on mRNA stability vary for different mRNAs and are cell type-dependent (50). Interestingly, Lapucci et al. (33) observed that UVC-induced apoptosis was associated with elevation of the levels of the p45 isoform of AUF1 and an increase in p45·bcl-2 ARE complex formation in Jurkat cells. Here, we have observed that only the 42-kDa isoform is UV-cross-linked to radio-labeled AREbcl-2 transcripts, even though all four isoforms are present in cytoplasmic extracts of MV-4-11 leukemia cells. Thus, bcl-2 regulation may involve an AUF1 isoform-specific mechanism in a cell type fashion.

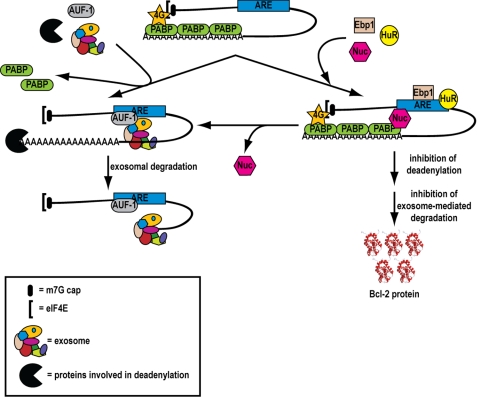

Based on our findings, we propose a model (Fig. 8) of how bcl-2 mRNA decay may occur in normal cells as opposed to some cancer cells where nucleolin is overexpressed in the cytoplasm. According to the model, in normal cells bcl-2 mRNA is rendered intrinsically unstable through the action of AUF1 and possibly other factors, which bind to the ARE and recruit the exosome to the mRNA. Once the mRNA is deadenylated, it is rapidly degraded by the exosome (41, 43) or is decapped and degraded by 5′-3′ exonucleolytic degradation (55). This prevents aberrant overexpression of bcl-2 mRNA and allows cells to enter apoptosis in response to certain stresses such as UV irradiation (33). The bcl-2 mRNA decay pathway described here is likely a protective mechanism used by normal cells to avoid malignant transformation. A different scenario can be envisioned in cancer cells such as CLL cells. The presence of abnormal high levels of nucleolin in the cytoplasm may cause a shift in the balance of mRNA regulation toward stabilization rather than degradation of certain messages, such as bcl-2 mRNA.

FIGURE 8.

Model of the regulation of decay of bcl-2 mRNA. Briefly, on the left side is shown a model for bcl-2 mRNA regulation in normal cells. AUF1 binds to the ARE region and recruits the exosome. Following deadenylation, the mRNA is rapidly degraded by the exosome. On the right side is shown the mechanism of bcl-2 mRNA regulation in cancer cells, such as CLL cells. Nucleolin is overexpressed in the cytoplasm of CLL cells. Binding of nucleolin to the ARE leads to decreased binding of AUF1 and reduced recruitment of the exosome. This leads to increased bcl-2 mRNA stability and Bcl-2 protein expression.

In summary, our findings provide new insights into the mechanism of nucleolin-mediated overexpression of Bcl-2 in cancer cells, more specifically on the stabilization of bcl-2 mRNA. This information should aid efforts to exploit nucleolin as a target for developing new therapies active in a variety of cancers including acute myeloid leukemia and CLL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. France Carrier for the purified GST-nucleolin and GST proteins and Dr. Nancy Maizels for the pMal-Nuc plasmids. We also thank David Burmeister for assistance with the ARE fragment binding assays, Dzmitry Fedarovich of the MUSC Protein Production Laboratory for the preparation of recombinant Nuc-His, and Dr. Visu Palanisamy, Dr. Jeff Wilusz, and John Anderson for helpful advice.

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grants CA 87553 (to E. K. S.) and CA 109254 (to D. J. F.) from the National Institutes of Health and an unrestricted grant from Antisoma Research Limited, UK (to D. J. F.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- CLL

- chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- ARE

- AU-rich element

- ECM

- evolutionarily conserved motif

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- NRE

- nucleolin recognition element

- Nuc-His

- nucleolin with the N-terminal deletion

- pre-rRNA

- preribosomal RNA

- RBD

- RNA binding domain

- R.E.

- range of extremes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Otake Y., Soundararajan S., Sengupta T. K., Kio E. A., Smith J. C., Pineda-Roman M., Stuart R. K., Spicer E. K., Fernandes D. J. (2007) Blood 109, 3069–3075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barreau C., Paillard L., Osborne H. B. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 7138–7150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiavone N., Rosini P., Quattrone A., Donnini M., Lapucci A., Citti L., Bevilacqua A., Nicolin A., Capaccioli S. (2000) FASEB J. 14, 174–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandyopadhyay S., Sengupta T. K., Fernandes D. J., Spicer E. K. (2003) Biochem. Pharmacol. 66, 1151–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myer V. E., Fan X. C., Steitz J. A. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 2130–2139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang W., Wagner B. J., Ehrenman K., Schaefer A. W., DeMaria C. T., Crater D., DeHaven K., Long L., Brewer G. (1993) Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 7652–7665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai W. S., Carballo E., Strum J. R., Kennington E. A., Phillips R. S., Blackshear P. J. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 4311–4323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gherzi R., Lee K. Y., Briata P., Wegmüller D., Moroni C., Karin M., Chen C. Y. (2004) Mol. Cell 14, 571–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piecyk M., Wax S., Beck A. R., Kedersha N., Gupta M., Maritim B., Chen S., Gueydan C., Kruys V., Streuli M., Anderson P. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 4154–4163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gueydan C., Droogmans L., Chalon P., Huez G., Caput D., Kruys V. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2322–2326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sengupta T. K., Bandyopadhyay S., Fernandes D. J., Spicer E. K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10855–10863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soundararajan S., Chen W., Spicer E. K., Courtenay-Luck N., Fernandes D. J. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 2358–2365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soundararajan S., Wang L., Sridharan V., Chen W., Courtenay-Luck N., Jones D., Spicer E. K., Fernandes D. J. (2009) Mol. Pharmacol. 76, 984–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hovanessian A. G., Puvion-Dutilleul F., Nisole S., Svab J., Perret E., Deng J. S., Krust B. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 261, 312–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mongelard F., Bouvet P. (2007) Trends Cell Biol. 17, 80–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouvet P., Diaz J. J., Kindbeiter K., Madjar J. J., Amalric F. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 19025–19029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghisolfi L., Joseph G., Amalric F., Erard M. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 2955–2959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghisolfi-Nieto L., Joseph G., Puvion-Dutilleul F., Amalric F., Bouvet P. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 260, 34–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serin G., Joseph G., Faucher C., Ghisolfi L., Bouche G., Amalric F., Bouvet P. (1996) Biochimie 78, 530–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ginisty H., Serin G., Ghisolfi-Nieto L., Roger B., Libante V., Amalric F., Bouvet P. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18845–18850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serin G., Joseph G., Ghisolfi L., Bauzan M., Erard M., Amalric F., Bouvet P. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13109–13116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginisty H., Amalric F., Bouvet P. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 14338–14343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh K., Laughlin J., Kosinski P. A., Covey L. R. (2004) J. Immunol. 173, 976–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y., Bhatia D., Xia H., Castranova V., Shi X., Chen F. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 485–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee P. T., Liao P. C., Chang W. C., Tseng J. T. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 5004–5013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen C. Y., Gherzi R., Andersen J. S., Gaietta G., Jürchott K., Royer H. D., Mann M., Karin M. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 1236–1248 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang Y., Xu X. S., Russell J. E. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2419–2429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J., Tsaprailis G., Bowden G. T. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 1046–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaidi S. H., Malter J. S. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17292–17298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fähling M., Steege A., Perlewitz A., Nafz B., Mrowka R., Persson P. B., Thiele B. J. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1731, 32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer S., Temme C., Wahle E. (2004) Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 197–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou C. F., Mulky A., Maitra S., Lin W. J., Gherzi R., Kappes J., Chen C. Y. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 3695–3706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lapucci A., Donnini M., Papucci L., Witort E., Tempestini A., Bevilacqua A., Nicolin A., Brewer G., Schiavone N., Capaccioli S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 16139–16146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Girvan A. C., Teng Y., Casson L. K., Thomas S. D., Jüliger S., Ball M. W., Klein J. B., Pierce W. M., Jr., Barve S. S., Bates P. J. (2006) Mol. Cancer Ther. 5, 1790–1799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang C., Maiguel D. A., Carrier F. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 2251–2260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanakahi L. A., Sun H., Maizels N. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 15908–15912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sokoloski K. J., Wilusz J., Wilusz C. J. (2008) Methods Enzymol. 448, 139–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bose S. K., Sengupta T. K., Bandyopadhyay S., Spicer E. K. (2006) Biochem. J. 396, 99–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tenenbaum S. A., Lager P. J., Carson C. C., Keene J. D. (2002) Methods 26, 191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ford L. P., Wilusz J. (1999) Methods 17, 21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mukherjee D., Gao M., O'Connor J. P., Raijmakers R., Pruijn G., Lutz C. S., Wilusz J. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 165–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finger L. D., Trantirek L., Johansson C., Feigon J. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 6461–6472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen C. Y., Gherzi R., Ong S. E., Chan E. L., Raijmakers R., Pruijn G. J., Stoecklin G., Moroni C., Mann M., Karin M. (2001) Cell 107, 451–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ireson C. R., Kelland L. R. (2006) Mol. Cancer Ther. 5, 2957–2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bates P. J., Kahlon J. B., Thomas S. D., Trent J. O., Miller D. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26369–26377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen C. M., Chiang S. Y., Yeh N. H. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 7754–7758 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner B. J., DeMaria C. T., Sun Y., Wilson G. M., Brewer G. (1998) Genomics 48, 195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allain F. H., Bouvet P., Dieckmann T., Feigon J. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 6870–6881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ishimaru D., Ramalingam S., Sengupta T. K., Bandyopadhyay S., Dellis S., Tholanikunnel B. G., Fernandes D. J., Spicer E. K. (2009) Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 1354–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu N., Chen C. Y., Shyu A. B. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 6960–6971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steinman R. A. (2007) Leukemia 21, 1158–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.David P. S., Tanveer R., Port J. D. (2007) RNA 13, 1453–1468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghisolfi L., Calastretti A., Franzi S., Canti G., Donnini M., Capaccioli S., Nicolin A., Bevilacqua A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20946–20955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee J. H., Jeon M. H., Seo Y. J., Lee Y. J., Ko J. H., Tsujimoto Y., Lee J. H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 42758–42764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao M., Wilusz C. J., Peltz S. W., Wilusz J. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 1134–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zuker M. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.