Abstract

Pyruvate formate-lyase-activating enzyme (PFL-AE) activates pyruvate formate-lyase (PFL) by generating a catalytically essential radical on Gly-734 of PFL. Crystal structures of unactivated PFL reveal that Gly-734 is buried 8 Å from the surface of the protein in what we refer to here as the closed conformation of PFL. We provide here the first experimental evidence for an alternate open conformation of PFL in which: (i) the glycyl radical is significantly less stable; (ii) the activated enzyme exhibits lower catalytic activity; (iii) the glycyl radical undergoes less H/D exchange with solvent; and (iv) the Tm of the protein is decreased. The evidence suggests that in the open conformation of PFL, the Gly-734 residue is located not in its buried position in the enzyme active site but rather in a more solvent-exposed location. Further, we find that the presence of the PFL-AE increases the proportion of PFL in the open conformation; this observation supports the idea that PFL-AE accesses Gly-734 for direct hydrogen atom abstraction by binding to the Gly-734 loop in the open conformation, thereby shifting the closed ↔ open equilibrium of PFL to the right. Together, our results lead to a model in which PFL can exist in either a closed conformation, with Gly-734 buried in the active site of PFL and harboring a stable glycyl radical, or an open conformation, with Gly-734 more solvent-exposed and accessible to the PFL-AE active site. The equilibrium between these two conformations of PFL is modulated by the interaction with PFL-AE.

Keywords: Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR), Enzyme Catalysis, Enzymes, Fluorescence, Radicals, Conformational Change, Enzyme Activation, Glycyl Radical Enzyme

Introduction

Pyruvate formate-lyase (PFL),2 a central enzyme in anaerobic glucose metabolism, utilizes a stable carbon-centered radical at Gly-734 to catalyze the reversible conversion of pyruvate and CoA to formate and acetyl-CoA (1–3). PFL is a 170-kDa homodimer, with each monomer comprising a 10-stranded α/β barrel with the active site located near the center of the barrel. The essential active site residues of PFL are Gly-734, Cys-418, and Cys-419; Gly-734 and Cys-418/Cys-419 reside on opposing finger loops in the PFL active site, with a Cα-Cα distance between Gly-734 and Cys-419 of ∼4.8 Å (4, 5). The roles of each of these residues in the mechanism of PFL have been elucidated through a series of elegant biochemical experiments as well as the insights gained from x-ray crystallography (supplemental Scheme S1) (5, 6). Gly-734 harbors a stable glycyl radical in the activated enzyme; however, it does not interact directly with the substrate pyruvate. Instead, the Gly-734 radical abstracts a hydrogen atom from Cys-419 to generate a thiyl radical, which is then transferred to Cys-418 (5–8). The thiyl radical on Cys-418 has been proposed to attack the carbonyl carbon on pyruvate to break the carbon-carbon bond (5, 6). Upon cleavage of pyruvate, the resulting formate anion radical abstracts a hydrogen atom from Gly-734 to regenerate the glycyl radical, and the acetyl moiety attached to Cys-418 reacts with CoA to produce acetyl-CoA (8–11). In this ping-pong mechanism, Cys-419 acts as a radical transporter between Gly-734 and Cys-418, with Cys-418 initiating the reaction with pyruvate (5, 8).

In aqueous solution, the PFL glycyl radical exhibits a characteristic doublet EPR signal (A = 1.5 mT) due to coupling to the remaining Cα-H on Gly-734 (supplemental Scheme S1) (2, 12). The doublet signal collapses to a singlet when activated PFL is diluted in D2O, pointing to an exchange of the remaining α-H on Gly-734 with solvent (2, 12). The unexpected exchange of deuterium from D2O into Gly-734 is mediated by the active site residue Cys-419, as demonstrated by the lack of exchange in the mutant C419S-PFL (13). These results provide evidence that the role for Cys-419 in the H/D exchange at Gly-734 is analogous to its role in the catalytic mechanism; specifically, the H/D exchange at Gly-734 is a result of a reversible exchange of an H• between Gly-734 and Cys-419. Such an abstraction of a hydrogen atom on Cys-419 by Gly-734• requires that these residues be in close proximity, and such close proximity is observed in the PFL crystal structures, which provide a Gly-734 (Cα) to Cys-419 (Sγ) distance of 3.7 Å in inactive PFL (5, 6).

The free radical at Gly-734 is generated by the pyruvate formate-lyase-activating enzyme (PFL-AE, supplemental Scheme S2) (14, 15). As a member of the radical S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) superfamily, PFL-AE utilizes a [4Fe-4S] cluster and AdoMet to generate the putative 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical intermediate responsible for hydrogen atom abstraction from Gly-734 of PFL (16–19). PFL-AE is a 28-kDa monomer, with the [4Fe-4S] cluster ligated to the protein via the CX3CX2C motif that is characteristic of the radical AdoMet superfamily enzymes (18–22). The fourth iron of the cluster is coordinated by the amino and carboxylate of AdoMet, as first demonstrated by ENDOR spectroscopy (23–26). The reduced [4Fe-4S]+ state of the cluster provides the electron necessary to reductively cleave AdoMet to generate the putative 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical, which then abstracts a hydrogen atom from Gly-734 to produce the glycyl radical and 5′-deoxyadenosine (17). Label transfer studies demonstrated the direct transfer of a deuteron from α(D2)-Gly-734-PFL to 5′-deoxyadenosine during activation of PFL by PFL-AE (supplemental Scheme S2) (27).

The direct and stereospecific hydrogen atom abstraction catalyzed by PFL-AE requires that the Gly-734 of PFL bind in the active site of PFL-AE. This glycyl residue is buried ∼8 Å from the surface of PFL in the crystal structure of the inactive enzyme. Although no crystal structures have been reported for the active form of PFL, the remarkable stability of the Gly-734 radical, together with the biochemical evidence for the interplay between Gly-734 and Cys-419 radicals outlined above, provides evidence that the activated form of PFL harbors a buried Gly-734 in a conformation similar to that observed in the inactive enzyme. Given the buried location of Gly-734, a critical question arises as to how PFL-AE accesses Gly-734 to catalyze a direct hydrogen atom abstraction.

The recently published x-ray crystal structure of PFL-AE complexed to AdoMet and a peptide has provided some insights into this activation process (28). In this structure the heptamer peptide RVSGYAV, corresponding to residues 731–737 in PFL, binds in the active site of PFL-AE such that the glycine Cα is 4.1 Å from the C5′ of AdoMet. The glycyl residue of the peptide is thus in excellent position for direct hydrogen atom abstraction by an AdoMet-derived 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical, consistent with the previous observation that this peptide acts as a substrate for PFL-AE (27). A model for the interaction between PFL and PFL-AE was generated based on this crystal structure and computational docking of the radical domain of PFL (residues 712–759) in the active site of PFL-AE; in this docking model, the glycine loop points in to the active site of PFL-AE and is positioned similarly to the heptamer peptide in the crystal structure (Gly-734 Cα-AdoMet C5′ distance of 4.6 Å) (28). Further modeling revealed that this radical domain, connected to the PFL β barrel via a short loop, could rotate about a single hinge point, with minimal steric clashes, to make Gly-734 accessible to PFL-AE (28).

In this paper we provide biophysical, spectroscopic, and biochemical evidence that PFL can in fact adopt an open conformation in which Gly-734 is more accessible. This open conformation is characterized by a less stable glycyl radical, less H/D exchange into the glycyl radical, a lower catalytic activity, an altered CD profile, and a lower melting temperature. The characteristics of the open conformation support our conclusions that in this conformation the Gly-734 is not buried within the PFL active site, but rather sits in a more exposed location that is accessible to binding by PFL-AE. We propose that the open and closed states of PFL are in equilibrium and that the position of equilibrium lies far to the “closed” state in the absence of PFL-AE, but that the presence of PFL-AE shifts this equilibrium toward the open state.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All purchased chemicals were of the highest purity commercially available. AdoMet was synthesized according to the procedure described previously (24). PFL was overexpressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3)plysS transformed with pKK/pfl and purified as described previously (17, 29). PFL-AE was overexpressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3)plysS transformed with pCAL-n-AE and purified as described previously (23, 30). Protein and iron assays were done as described previously (31, 32).

EPR Spectroscopy

EPR spectra were recorded in a Bruker ER-200D-SRC spectrometer at 60 K and 9.37 GHz, with 19-μW microwave power, 100-kHz modulation frequency, and 5-G modulation amplitude; each spectrum shown is the sum of two scans. K2(SO3)2NO was used as a standard to determine the quantity of the glycyl radical, according to the method described previously (33).

PFL Activation

PFL activation was conducted in an anaerobic (Mbraun) chamber at <2 ppm O2. Activation mixes contained 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 100 mm KCl, 10 mm oxamate, 10 mm DTT, 50 or 100 μm PFL, 0.5–100 μm PFL-AE, 500 μm AdoMet, and 100 μm 5-deazariboflavin. The mixes were transferred into an EPR tube, placed in an ice-water bath, and illuminated by a 300-W halogen light for varying times. After illumination, samples were frozen in liquid N2.

PFL Reactivation

After 50 μm PFL was activated with 50 μm PFL-AE for 2 and 3 h (four samples for each illumination time) as described in the previous paragraph, one sample was frozen in liquid N2. The other three samples were mixed with additional 50 μm PFL-AE, 500 μm AdoMet, and 100 μm 5-deazariboflavin under anaerobic conditions, illuminated for 10, 20, and 30 min respectively, and frozen in liquid N2. After examination by EPR, the reactivated samples were thawed in the Mbraun box, illuminated for an additional 100 min, and frozen in liquid N2.

H/D Exchange of α-Hydrogen of Gly-734 Radical

PFL was activated as described above, using PFL:PFL-AE ratios of 100:1, 10:1, and 1:1. EPR spectra were recorded, and then the samples were thawed in the anaerobic chamber. Each sample was then diluted with either 1 or 3 volumes of D2O buffer containing 100 mm Tris-Cl, pD 8.2, and 100 mm KCl. Immediately after mixing, each sample was transferred into an EPR tube and frozen in liquid N2.

PFL Activity Assay

PFL (100 μm) was completely activated by 1, 0.1, or 0.01 equivalent of PFL-AE, as determined by EPR spin quantification of glycyl radicals. Activated PFL (1 μl) was added into buffer (99 μl) containing 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, and 100 mm KCl. An aliquot of this diluted sample (5 μl) was taken out and mixed with 795 μl of the coupling assay mix, and the rate of PFL turnover was determined spectrophotometrically as described previously (1, 29).

CD Sample Preparation

The samples described under “PFL Activation” were also used for CD spectroscopy after diluting in phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) to a final PFL concentration of 3 mg/ml. These samples were thawed in an anaerobic chamber (COY) and loaded into a 0.1-mm optical path quartz CD measuring cell. The cell was then sealed with a rubber septum to maintain an anaerobic atmosphere during the CD measurement.

To subtract the contribution of PFL-AE (which is present in the activation mix) to the CD spectra, background solutions containing every component in the PFL activation mix except PFL were prepared. These background solutions were prepared in the same way as the activation mix samples.

CD Spectroscopy

The CD spectra were measured in a JASCO J-710 spectropolarimeter in the wavelength range 170–300 nm. The scan speed was 50 nm/min, the data pitch was 0.1 nm, the bandwidth was 0.5 nm, and four scans were accumulated per sample. During the measurement, the spectrometer was purged with N2 gas at 60 liters/min, and the measuring chamber was purged by N2 from another separated line to keep the samples under anaerobic conditions. CD spectra were analyzed for changes in α-helical content by using the program CDPro (34).

Fluorescence Spectroscopy Sample Preparation

All procedures were conducted in an anaerobic (Mbraun) chamber at <1 ppm O2. The sample solution contained 0.5 μm PFL, mixed with 0, 0.5, 2.5, or 5 μm PFL-AE, 5 μm AdoMet, 100 μm oxamate, and 100 μm DTT in buffer containing 0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, and 0.1 m KCl to make a final volume of 2 ml. The samples were loaded into a 1-cm optical path quartz cell. To examine the fluorescence background of PFL-AE, background solutions containing all components in the PFL mix except PFL were prepared.

Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Fluorescence data were collected at Fluorescence Innovations, Inc. on a prototype ultraviolet fluorescence lifetime spectrometer. Temperature studies were conducted over the range 20–80 °C. A 2 °C temperature increment was used throughout the experiment. The sample temperature was controlled with a four-cuvette turret from Quantum Northwest (Spokane, WA). Standard 10-mm internal pathlength fused silica cuvettes were used in these experiments. The excitation source in the instrument is a very compact frequency-doubled dye laser, which was operated at 294 nm for these experiments. The excitation wavelength was set at 294 nm to minimize contribution of tyrosine to the observed fluorescence. Relevant parameters include 0.2 μJ of energy/pulse, 1,000-Hz pulse repetition frequency, and 0.5-ns pulse duration. The fluorescence detection module is a Varian Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer, which has been modified by replacing the standard photomultiplier tube with a Hamamatsu R-7400 photomultiplier tube. Time domain fluorescence data were recorded with a proprietary transient digitizer that generates a complete fluorescence decay curve on every laser shot. The digitizer, which employs an analog memory, samples at 1 gigasample/s (i.e. 1-ns spacing in the time domain). The effective sampling rate is increased to a time point every 200 ps via 5× interleaving. Each fluorescence decay waveform is averaged over 1,000 laser shots, corresponding to 1-s acquisition time/waveform. Fluorescence data were recorded every 3 nm from 290 nm to 410 nm for every temperature; the emission bandpass was set at 5 nm. The photomultiplier tube was biased at 400 V for these experiments. PFL-AE concentrations of 0, 0.005, 0.050, 0.50, 2.5, and 5.0 μm and a fixed PFL concentration of 0.50 μm were examined in these experiments (35).

The data were collected in the form of wavelength-time matrices, i.e. fluorescence decay curves at a series of emission wavelengths. However, the fluorescence decay properties for a given sample (as defined by relative amount of PFL-AE and temperature) are only slightly dependent on the emission monitoring wavelength. Likewise, the process of protein unfolding does not markedly affect the shape of the fluorescence spectrum. Thus, the data were analyzed in intensity format at a single emission wavelength, 341 nm. This wavelength was chosen because it is close to the emission wavelength of maximum intensity (ca. 334 nm) and situated to sufficiently long wavelength to avoid interference by solvent Raman scattering. The area under the fluorescence decay curves is proportional to the fluorescence intensity that would be measured in a state-state fluorescence experiment.

The data were analyzed via the Linear Extrapolation Method of Greene and Pace via nonlinear least squares (36, 37) as proposed by Santoro and Bolen (38). The parameters used to fit the data are slope and intercept for the pretransition region, slope, and intercept for the posttransition region, and two or three parameters to describe the free energy change of unfolding, i.e.,

where Tm is the midpoint of the unfolding curve, ΔHm is the enthalpy change for unfolding at Tm, and ΔCp is the heat capacity change for unfolding. The very good fits with two parameters (Tm and ΔHm) were not appreciably improved by including the ΔCp term.

RESULTS

Stability of the PFL Glycyl Radical Is Affected by the Presence of PFL-AE

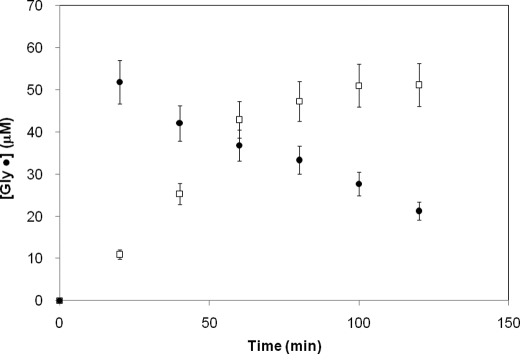

PFL can be fully activated, defined as possessing one glycyl radical/PFL dimer due to the half-of-sites reactivity of PFL, with catalytic amounts of PFL-AE. Under these conditions, activation is quite slow, with full activation requiring ∼90 min at a 1:100 mol ratio of PFL-AE to PFL (Fig. 1). Under these conditions, the PFL glycyl radical is remarkably stable, with a half-life estimated at ≥24 h at 30 °C (26). Full activation of PFL by stoichiometric amounts of PFL-AE is more rapid (Fig. 1); however, it is followed immediately by the time-dependent loss of the glycyl radical. The loss of the glycyl radical is likely a result of nondestructive quenching by the high concentrations of DTT in the assays, as we have reported previously (29); it is, however, dramatically faster in the presence of stoichiometric PFL-AE (t½ ∼ 90 min) than in the presence of catalytic amounts of PFL-AE (t½ ≥ 24 h). The observation that PFL is more prone to reductive quenching when activated with a stoichiometric, rather than catalytic, quantity of PFL-AE suggests that the interaction with PFL-AE favors an alternate conformation of PFL in which Gly-734 is more solvent-exposed; we heretofore refer to this as the open conformation of PFL.

FIGURE 1.

Spin quantification of glycyl radicals in PFL activated by different quantities of PFL-AE as a function of time. PFL (50 μm) was illuminated with either 50 μm (●) or 0.50 μm (□) PFL-AE in a buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6) containing 500 μm AdoMet, 100 μm 5-deazariboflavin, 100 mm KCl, 10 mm oxamate, and 10 mm DTT. EPR parameters: T, 60 K; microwave frequency, 9.37 GHz; power, 19 mW; modulation amplitude, 5 G.

Gly-734 H/D Exchange Is Affected by the Presence of PFL-AE

The α-H on Gly-734 of activated PFL undergoes H/D exchange in D2O, as evidenced by the doublet EPR signal collapsing to a singlet in D2O (2, 3, 13). The active site residue Cys-419 has been demonstrated to be essential for the H/D exchange at Gly-734 because the mutant C419S-PFL does not undergo H/D exchange (13). These results provide evidence that the Gly-734 radical in activated PFL abstracts H• from Cys-419 to generate a thiyl radical, which can subsequently abstract a hydrogen from Gly-734 to regenerate the glycyl radical; this reversible H• abstraction involving a species with an exchangeable hydrogen (Cys-419) results in deuterium exchange into the Gly-734 (supplemental Scheme S3). If the presence of PFL-AE shifts the closed ↔ open equilibrium of PFL to the right, as suggested above, then we might also expect to see an effect on the H/D exchange for Gly-734• in the presence of PFL-AE: specifically, we would expect H/D exchange to occur more slowly in the presence of PFL-AE due to the Gly-734 spending less time adjacent to Cys-419 in the active site.

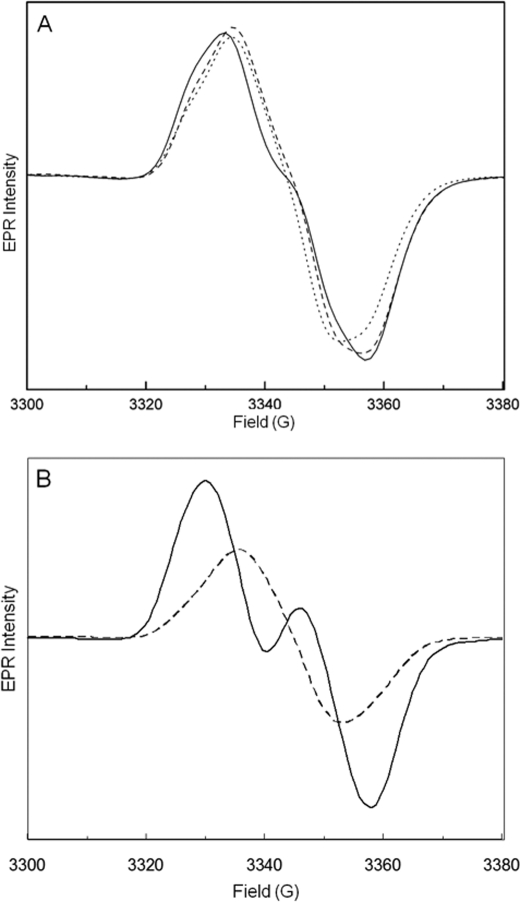

In an attempt to detect an effect of PFL-AE on the rate of H/D exchange at Gly-734 in activated PFL, we fully activated 100 μm PFL with either 1, 0.1, or 0.01 equivalent of PFL-AE and then diluted with D2O buffer and immediately froze the samples (<2-min incubation in D2O) for examination by EPR. The samples diluted to a final [D2O] of 50% (Fig. 2) show glycyl radical EPR spectra with varying degrees of collapse of the doublet signal observed in H2O; in fact the degree of collapse of the doublet signal increases as the amount of PFL-AE present decreases. This increased doublet collapse at lower concentrations of PFL-AE is evidence that at these lower concentrations, Gly-734 spends more time in the active site near Cys-419 and thus undergoes more rapid H/D exchange. At high ratios of PFL-AE to PFL, however, less collapse of the doublet EPR signal is observed, consistent with these higher ratios shifting the PFL equilibrium in favor of an open conformation, in which Gly-734 is away from its resting position near Cys-419. Samples prepared with final [D2O] of 75% showed a comparable effect: higher ratios of PFL-AE to PFL decrease the degree of H/D exchange, as measured by the breadth of the glycyl radical EPR signal (data not shown). If the effect of PFL-AE in these H/D exchange experiments is simply to shift the PFL equilibrium toward the open conformation, then we would expect complete H/D exchange in all samples, regardless of the presence of PFL-AE, if the samples are allowed to equilibrate fully in the D2O buffer; consistent with this expectation, all samples prepared with a given concentration of D2O show the same degree of doublet collapse when incubated in the D2O buffer for extended periods prior to freezing (data not shown). Together, these results demonstrate that at higher concentrations of PFL-AE, the Gly-734• is less able to undergo H/D exchange mediated by Cys-419; these results support our proposal that the presence of PFL-AE favors an open conformation of PFL in which the Gly-734 loop has moved from its buried location in the PFL structure.

FIGURE 2.

EPR evidence for altered H/D exchange. A, EPR spectra of PFL activated by different quantities of PFL-AE and then mixed with D2O buffer. The samples were made by fully activating 100 μm PFL and then diluting 1:1 with D2O buffer. The solid line is 100 μm PFL activated by 100 μm PFL-AE for 30 min; dashed line is 100 μm PFL activated by 10 μm PFL-AE for 2 h; dotted line is 100 μm PFL activated by 1 μm PFL-AE for 2 h. The PFL activation mix contained 100 μm PFL, 100 μm, 10 μm, or 1 μm PFL-AE, 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 100 mm KCl, 500 μm AdoMet, 100 μm 5-deazariboflavin, 10 mm oxamate, and 10 mm DTT. The D2O buffer contained 100 mm Tris-HCl, pD 8.2, and 100 mm KCl. B, reference spectra showing the PFL glycyl radical (generated by activating with 0.01 equivalent of PFL-AE) in H2O (solid line) and after full exchange with 50% D2O (dashed line). EPR parameters: T, 60 K; microwave frequency, 9.37 GHz; power, 19 mW; modulation amplitude, 5 G.

Enzymatic Activity of Fully Activated PFL Is Affected by the Presence of PFL-AE

If the presence of PFL-AE favors an open conformation of PFL in which Gly-734 is not in its resting position in the active site, this should be reflected in the effect of PFL-AE on the activity of activated PFL because PFL catalysis requires direct interaction between Gly-734 and Cys-419 (supplemental Scheme S1). To examine this possibility, the enzymatic activity of PFL fully activated (as measured by glycyl radical content) with 1, 0.1, or 0.01 equivalent of PFL-AE was investigated. The activation of PFL with 1 equivalent of PFL-AE was carried out for 30 min, whereas activations with 0.1 and 0.01 equivalents of PFL-AE were carried out for 2 h. EPR spectroscopy of the resulting activated PFL samples confirmed the presence of one glycyl radical/PFL dimer, as expected for fully activated PFL (Table 1). Although all three PFL samples contained comparable amounts of glycyl radical, the specific activities of the PFL samples decreased as the PFL-AE concentrations increased (Table 1). These results are consistent with the H/D exchange results described in the previous section and provide support for the idea that the presence of PFL-AE favors an open conformation of PFL in which Gly-734 is located away from the PFL active site.

TABLE 1.

PFL activity is affected by the presence of PFL-AE

| PFL-AE:PFL | Ill. Timea | [Gly•]b | Activityc |

|---|---|---|---|

| min | μm | units/nmol | |

| 1:1 | 30 | 98 (±10) | 6.6 (±1) |

| 1:1 | 120 | 23 (±10) | NDd |

| 1:10 | 120 | 105 (±10) | 22 (±2) |

| 1:100 | 120 | 102 (±10) | 23 (±2) |

a Ill. Time is the time allowed for activation of PFL under photoreduction conditions.

b Glycyl radical was determined by EPR spin quantification.

c PFL activity is defined as 1 unit = 1 μmol of pyruvate turnover/min.

d Not determined; activity was below our limits of detection.

Spectroscopic Evidence for a Structural Change in PFL

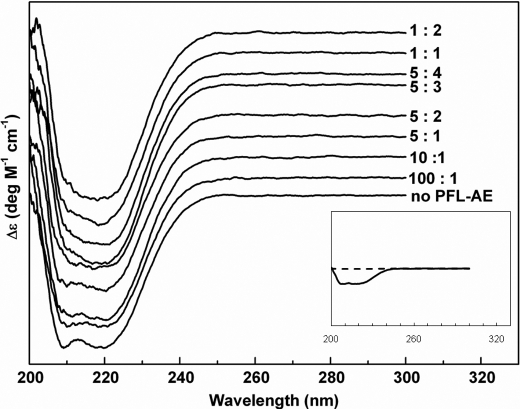

The movement of Gly-734 from the buried active site of PFL to an open conformation accessible to the active site of PFL-AE requires a conformational change in PFL. The CD spectra of PFL in the presence of 0 to 2 equivalents of PFL-AE provide evidence for such a structural change (Fig. 3). The intensity of the peak at 209 nm, one of the indicators of α-helical structure (39), decreases as the amount of PFL-AE increases, pointing to a small decrease in α-helical structure in PFL upon interaction with PFL-AE. Analysis of these CD spectra indicates that the α-helical content of PFL decreases by ∼3% in the presence of 1 molar equivalent of PFL-AE. Although the CD changes are quite small, they are consistent with our previous observation that the open conformation of PFL could be achieved with relatively little change in secondary structure, even with a simple rotation about a single hinge point (28). The CD data together with the fluorescence data described in the following section have allowed us to estimate a dissociation constant for the PFL·PFL-AE complex in the low micromolar range (<10 μm).

FIGURE 3.

CD spectra of 50 μm PFL activated by 0, 5, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 100 μm PFL-AE in the presence of 500 μm AdoMet, 100 μm 5-deazariboflavin, 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 100 mm KCl, 10 mm oxamate, and 10 mm DTT for 2 h. Each is a difference spectrum of PFL in activation mix minus the same activation mix lacking PFL. The numbers shown for each difference spectrum correspond to the PFL:PFL-AE ratios. The inset shows the contribution of PFL-AE to the CD spectra on the same scale as the main figure. Solid line is PFL-AE at 50 μm, and dashed line is PFL-AE at 1 μm. CD parameters: wavelength range, 170–300 nm; scan speed, 50 nm/min; data pitch, 0.1 nm; bandwidth, 0.5 nm; four scans accumulated.

PFL-AE Induces Thermal Instability to PFL

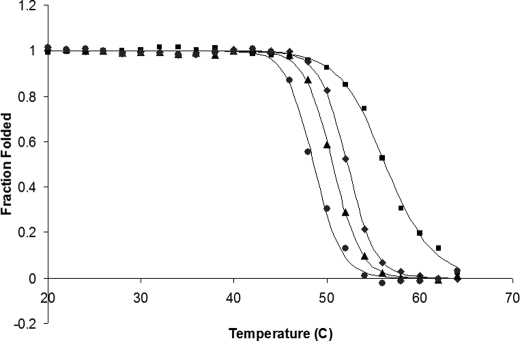

The open conformation of PFL that is favored at high PFL-AE:PFL ratios might also be expected to decrease the thermal stability of PFL due to removal of a core domain of the PFL structure; we have investigated this possibility by using fluorescence-detected protein unfolding. Fig. 4 illustrates the unfolding curves for four conditions, PFL alone and in the presence of 1, 5, and 10 molar equivalents of PFL-AE. With increasing quantities of PFL-AE, the melting temperature of PFL decreases, indicating that PFL is less thermally stable in the presence of PFL-AE than in its absence (note that higher PFL-AE:PFL ratios are used in these experiments than in others described in this paper; this was necessary to drive the equilibrium toward the PFL·PFL-AE complex at the low PFL concentrations used for the fluorescence experiments). Based on the fluorescence lifetimes, the apparent fluorescence quantum yields of PFL and AE are comparable with other proteins. On a molar basis, the PFL fluorescence is much stronger than that of PFL-AE (by ∼7 times) because of its much larger number of tryptophans. At the lower 1:1 ratio the PFL dominates the fluorescence signal, whereas at higher ratios the contribution from PFL-AE would be significant. Ideally, one should correct the raw thermal denaturation data for the contribution of free PFL-AE, which has a melting temperature of 53 °C. This would require knowledge of the temperature dependence of the binding affinity between PFL and PFL-AE from 20 °C to a few degrees above the melting temperature, information we do not currently have. However, simulations showed that even assuming an unrealistically low degree of complexation between PFL and PFL-AE, our conclusion that complex formation is responsible for the decrease in melting temperature was unaffected. Further, it is clear that even at the low 1:1 ratio of PFL-AE to PFL, where the PFL fluorescence dominates the melting curve, the presence of PFL-AE produces a measurable decrease in the thermal stability of PFL.

FIGURE 4.

PFL melting curves as measured by fluorescence spectroscopy. The fraction of PFL folded as a function of temperature is shown for PFL alone at 0.5 μm (■) or PFL in the presence of 1 (♦), 5 (▴), or 10 (●) molar equivalent of PFL-AE. Solid lines are the theoretical fits generated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” PFL-AE alone has a melting temperature of 53 °C. Fluorescence spectroscopy parameters: excitation wavelength, 294 nm; collecting wavelength, 290–410 nm; step, 3 nm; average, 200; photomultiplier tube setting, 400 V. The excitation wavelength was set at 294 nm to minimize contribution of tyrosine to the observed fluorescence.

DISCUSSION

The catalytically essential glycyl radical of PFL is located at Gly-734, a residue that is buried 8 Å from the surface of PFL in the resting enzyme (5). The buried location of Gly-734, coupled with the evidence for direct hydrogen atom abstraction from Gly-734 catalyzed by PFL-AE, suggest that conformational changes in one or both proteins are a requisite component of the activation reaction. Here, we describe a set of experiments that together provide evidence that PFL can exist in an alternate open conformation in which Gly-734 is in a more solvent-exposed location and that the equilibrium shifts toward this open conformation in the presence of PFL-AE.

The main line of evidence for increased solvent accessibility of the PFL Gly-734 residue in the presence of PFL-AE is the decreased stability of the glycyl radical under these conditions. The Gly-734 radical has been reported to be remarkably stable under anaerobic conditions, with a half-life of greater than 24 h at 30 °C (26). This extraordinary stability is consistent with the results described herein where catalytic amounts of PFL-AE are used to activate the PFL; under these conditions, the radical remains stable for extended periods of time. However, when the amount of PFL-AE used to activate PFL was increased from catalytic to stoichiometric amounts, a dramatic decrease in glycyl radical stability was observed. As expected, under these conditions the PFL was fully activated much more rapidly than when catalytic amounts of PFL-AE were used; however, the rapid and complete activation was followed by a steady loss in the amount of glycyl radical present. PFL that had lost its glycyl radical during the course of an extended incubation with stoichiometric PFL-AE could be reactivated by subjecting it again to activation conditions; this ability to regenerate the glycyl radical lost upon long incubation demonstrates that the glycyl radical is lost by nondestructive quenching, most likely by the high concentrations of DTT in the buffer, which we have previously shown to quench the PFL glycyl radical nondestructively (29). These results together provide evidence that at higher concentrations of PFL-AE, the Gly-734 radical of PFL has a greater probability of undergoing nondestructive quenching; this observation suggests that the presence of PFL-AE favors an open conformation of PFL in which Gly-734 is more solvent-exposed.

Two additional lines of evidence support our conclusion that the presence of PFL-AE favors a conformation of PFL in which Gly-734 is away from its typical location in the active site. First, we find that the H/D exchange at Gly-734 is slowed in the presence of stoichiometric amounts of PFL-AE. H/D exchange at Gly-734 requires that this residue be in close proximity to Cys-419, which mediates the exchange via reversible H atom abstraction (supplemental Scheme S3). When PFL is activated with catalytic amounts of PFL-AE, the observed H/D exchange is consistent with that previously reported (13). However, as the ratio of PFL-AE to PFL is increased to 0.1 and 1.0, the extent of H/D exchange at short incubation times decreases, as indicated by the decreased collapse of the Gly-734 radical doublet signal to a singlet. The only plausible explanation for this observation is that PFL can exist in an alternate conformation, favored in the presence of PFL-AE, in which Gly-734 is not buried in the PFL active site and is not a mere 4.8 Å (Cα-Cα) from Cys-419. Second, we have found, quite remarkably, that the activity of activated PFL can vary dramatically in response to the presence of PFL-AE, despite having equivalent quantities of glycyl radical. When several PFL samples were fully activated with either catalytic or stoichiometric quantities of PFL-AE, as judged by the glycyl radical content of the activated PFL, it was found that the PFL activated with stoichiometric PFL-AE actually had a lower catalytic activity. Again, this observation is best explained by the presence of an alternate conformation of PFL, favored in the presence of PFL-AE, in which Gly-734 is not present in its normal “resting” location in the PFL active site.

We have also presented evidence for general conformational changes in PFL that are favored in the presence of PFL-AE. The first involves changes in the CD spectral properties of PFL, specifically a decrease in the intensity of the 209 nm feature as the PFL-AE to PFL ratio increases. This change, although admittedly quite small, is reproducible and points to a small decrease in α-helical character of PFL in the presence of PFL-AE. Indeed, only a small change in α-helical character would be expected as a result of a conformational change of the Gly loop because this loop represents only a small portion of a very large protein with significant α-helical content.

Fluorescence-monitored melting curves of PFL in the absence and presence of PFL-AE also provide evidence of an alternate conformation of PFL that is favored in the presence of PFL-AE. Interestingly, we observe measurable decreases in the melting temperature of PFL in the presence of increasing amounts of PFL-AE, indicating that the conformation favored in the presence of PFL-AE has a lower thermal stability, precisely what we would expect upon removing a core domain from the PFL structure.

To gain insight into the nature of the open conformation of PFL, it is helpful to know more about both PFL and a related protein, YfiD. (i) Activated PFL is stable only under strictly anaerobic conditions; in the presence of O2, activated PFL is cleaved at the site of the glycyl radical (Gly-734) to form two fragments of 82 kDa (residues 1–733) and 3 kDa. (ii) The O2-mediated cleavage of PFL is irreversible and results in complete loss of enzyme activity; however YfiD, a 14-kDa protein from E. coli, can interact with the 82-kDa PFL fragment to recover the full activity of PFL (40). YfiD has substantial sequence homology to the C-terminal portion of PFL (residues 734–759) and is thought to possibly form a complex with the PFL(1–733) peptide (40). These results with YfiD suggest that the C-terminal portion of PFL, which includes Gly-734, can function in a somewhat modular fashion, such that when the protein is cleaved at Gly-734, the YfiD module can “plug in” to regenerate a functional enzyme. This modular nature of the C-terminal region of PFL is consistent with this region being capable of moving out of its position in the resting enzyme and back in, thus generating open and closed conformations of PFL. We have previously shown that such conversion between open and closed states of PFL could be accomplished with minimal steric clashes by a simple rotation about a single hinge point (28).

Our results lead us to a model for PFL activation by PFL-AE in which PFL has two possible conformational states in equilibrium (Fig. 5); the first is a closed state, which is the state that has been characterized by x-ray crystallography and which is believed to be the resting state of the enzyme. In this state, the Gly-734 is buried 8 Å from the surface of the protein and is located in the active site in close proximity to the catalytically essential Cys-418 and Cys-419 residues. In this state, the Gly-734 radical is protected from solvent and thus remarkably stable. The Gly-734 radical is also able to undergo H/D exchange due to its proximity to Cys-419, and it is able to participate in the PFL enzymatic reaction due to its location in the active site. PFL in this conformation therefore harbors a stable glycyl radical and is catalytically active. The second conformational state for PFL is an open state, for which no structural information is available. In this state, Gly-734 is solvent-exposed and thus prone to quenching and less stable than in the closed state. The Gly-734 in this state is not in its structurally characterized position in the active site and thus is not able to undergo H/D exchange via Cys-419 and is not able to catalyze the PFL reaction. We propose that the structure of the open state of PFL is one in which the C-terminal domain, corresponding to approximately residues 712–759, has undergone a rotation such as to render Gly-734 in a more exposed location (Fig. 5). Such a rotation could be accompanied by small changes in the helical content of PFL, as was evidenced in the CD spectroscopy, and would also be expected to decrease the thermal stability of PFL, due to removal of a core domain from its usual location. Our evidence suggests that the open and closed states of PFL are in equilibrium and that the position of equilibrium lies far to the closed state in the absence of PFL-AE, but that the presence of PFL-AE shifts this equilibrium toward the open state.

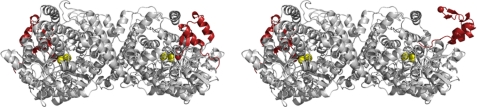

FIGURE 5.

Schematic representation of the crystal structure of PFL (pfl2, closed conformation, left) and a model for the open conformation (right). The radical domain is shown in red, with Gly-734 represented as a sphere, and the active site residues Cys-418 and Cys-419 are shown as yellow spheres. The radical domain is connected to the barrel of PFL via a flexible loop, which is expected to allow the radical domain to access a more solvent-exposed conformation; the model shown here for the open conformation was generated by manual rotation of the radical domain in PyMOL and is intended to illustrate the accessibility of Gly-734. In the model for the open conformation, only a single radical domain in the PFL dimer is shown in the open conformation, consistent with the half-of-sites reactivity of PFL.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM54608 (to J. B. B.). This work was also supported by Montana Board of Research and Commercialization Technology Grant 08-48 (to G. D. G.). The Astrobiology Biogeocatalysis Research Center is supported by the NASA Astrobiology Institute Grant NAI05-19.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Schemes S1–S3.

- PFL

- pyruvate formate-lyase

- PFL-AE

- PFL-activating enzyme.

REFERENCES

- 1.Knappe J., Blaschkowski H. P., Gröbner P., Schmitt T. (1974) Eur. J. Biochem. 50, 253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner A. F., Frey M., Neugebauer F. A., Schäfer W., Knappe J. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 996–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unkrig V., Neugebauer F. A., Knappe J. (1989) Eur. J. Biochem. 184, 723–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rödel W., Plaga W., Frank R., Knappe J. (1988) Eur. J. Biochem. 177, 153–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker A., Fritz-Wolf K., Kabsch W., Knappe J., Schultz S., Wagner A. F. (1999) Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 969–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker A., Kabsch W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40036–40042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knappe J., Sawers G. (1990) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 6, 383–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plaga W., Vielhaber G., Wallach J., Knappe J. (2000) FEBS Lett. 466, 45–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plaga W., Frank R., Knappe J. (1988) Eur. J. Biochem. 178, 445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parast C. V., Wong K. K., Kozarich J. W., Paisach J., Magliozzo R. S. (1995) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 10601–10602 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehtiö L., Leppänen V.-M., Kozarich J. W., Goldman A. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 58, 2209–2212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knappe J., Elbert S., Frey M., Wagner A. F. (1993) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 21, 731–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parast C. V., Wong K. K., Lewisch S. A., Kozarich J. W., Peisach J., Magliozzo R. S. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 2393–2399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knappe J., Schmitt T. (1976) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 71, 1110–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaschkowski H. P., Neuer G., Ludwig-Festl M., Knappe J. (1982) Eur. J. Biochem. 123, 563–569 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broderick J. B., Duderstadt R. E., Fernandez D. C., Wojtuszewski K., Henshaw T. F., Johnson M. K. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 7396–7397 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henshaw T. F., Cheek J., Broderick J. B. (2000) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 8331–8332 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheek J., Broderick J. B. (2001) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 6, 209–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sofia H. J., Chen G., Hetzler B. G., Reyes-Spindola J. F., Miller N. E. (2001) Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 1097–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krebs C., Henshaw T. F., Cheek J., Huynh B.-H., Broderick J. B. (2000) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 12497–12506 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Külzer R., Pils T., Kappl R., Hüttermann J., Knappe J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 4897–4903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frey P. A., Magnusson O. T. (2003) Chem. Rev. 103, 2129–2148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krebs C., Broderick W. E., Henshaw T. F., Broderick J. B., Huynh B. H. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 912–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsby C. J., Hong W., Broderick W. E., Cheek J., Ortillo D., Broderick J. B., Hoffman B. M. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 3143–3151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsby C. J., Ortillo D., Broderick W. E., Broderick J. B., Hoffman B. M. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 11270–11271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsby C. J., Ortillo D., Yang J., Nnyepi M. R., Broderick W. E., Hoffman B. M., Broderick J. B. (2005) Inorg. Chem. 44, 727–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frey M., Rothe M., Wagner A. F., Knappe J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 12432–12437 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vey J. L., Yang J., Li M., Broderick W. E., Broderick J. B., Drennan C. L. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 16137–16141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nnyepi M. R., Peng Y., Broderick J. B. (2007) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 459, 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Broderick J. B., Henshaw T. F., Cheek J., Wojtuszewski K., Smith S. R., Trojan M. R., McGhan R. M., Kopf A., Kibbey M., Broderick W. E. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 269, 451–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradford M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beinert H. (1978) Methods Enzymol. 54, 435–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aasa R., Vänngård T. (1975) J. Magn. Res. 19, 308–315 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sreerama N., Woody R. W. (2004) Methods Enzymol. 383, 318–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker S. N., McCleskey T. M., Pandey S., Baker G. A. (2004) Chem. Commun. 21, 940–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greene R. F., Jr., Pace C. N. (1974) J. Biol. Chem. 249, 5388–5393 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pace C. N., Shaw K. L. (2000) Proteins Struct. Funct. Gen. Suppl. 4, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santoro M. M., Bolen D. W. (1988) Biochemistry 27, 8063–8068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenfield N. J. (2004) Methods Mol. Biol. 261, 55–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner A. F., Schultz S., Bomke J., Pils T., Lehmann W. D., Knappe J. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 285, 456–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.