Abstract

GMP catalyzes the formation of GDP-Man, a fundamental precursor for protein glycosylation and bacterial cell wall and capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis. Crystal structures of GMP from the thermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima in the apo form, in complex with the substrates mannose-1-phosphate or GTP and bound with the end product GDP-Man in the presence of the essential divalent cation Mg2+, were solved in the 2.1–2.8 Å resolution range. The T. maritima GMP molecule is organized in two separate domains: a N-terminal Rossman fold-like domain and a C-terminal left-handed β-helix domain. Two molecules associate into a dimer through a tail-to-tail arrangement of the C-terminal domains. Comparative analysis of the structures along with characterization of enzymatic parameters reveals the bases of substrate specificity of this class of sugar nucleotidyltransferases. In particular, substrate and product binding are associated with significant changes in the conformation of loop regions lining the active center and in the relative orientation of the two domains. Involvement of both the N- and C-terminal domains, coupled to the catalytic role of a bivalent metal ion, highlights the catalytic features of bacterial GMPs compared with other members of the pyrophosphorylase superfamily.

Keywords: Carbohydrate, Carbohydrate Metabolism, Cell Wall, Enzyme Structure, Nucleoside Nucleotide Metabolism

Introduction

Nucleoside-5′-diphosphosugars (NDP-sugars),3 referred to as sugar nucleotides, represent the most common form of activated donor substrates used by glycosyltransferases in various biosynthetic pathways. GDP-Man, the activated form of Man, is required for mannosylation processes within the cell and is central for protein glycosylation and glycophospholipid anchor synthesis in eukaryotes. In bacteria, GDP-Man is an essential precursor of Man-containing polysaccharides found in capsular and other cell wall components. In this context, the genomes of thermophilic anaerobes are particularly rich in carbohydrate-active enzymes to produce exopolysaccharides to confer various cell surface-associated functions (1).

In addition to its direct utilization for synthetic purposes, GDP-Man can be enzymatically converted to other GDP-sugars, such as GDP-l-fucose, GDP-d-mannuronate, and GDP-d-rhamnose, which in turn are incorporated into various glycoconjugates. GDP-Man is synthesized from the glycolytic intermediate fructose-6-phosphate and GTP in three steps. A phosphomannose isomerase (PMI) first converts fructose-6-phosphate to mannose-6-phosphate, which is then converted to mannose-1-phosphate (Man1P) by a phosphomannomutase. Finally, the GMP/Man1P guanylyltransferase catalyzes the condensation of GTP and Man1P to form GDP-Man. The GMP enzyme, also referred to as PMI (EC 2.7.7.13) and first characterized in Arthrobacter sp. (2), has been described in several species. In some bacterial species, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the noncontiguous GMP and PMI activities reside on separate domains of a bifunctional enzyme (3). Although the sequences from mono- and bifunctional PMIs, classified as PMI of type I and II, respectively, lack significant overall homology, the sequence associated to GMP activity has been conserved during the course of evolution (4). Indeed, at the sequence level, monofunctional GMPs and the GMP domain of bifunctional PMIs share the consensus sequence GXGXRXnK, which is the signature motif of pyrophosphorylases (PPases). Both groups carry also a F(V)EKP motif described as part of the GMP active site (4, 5). All of the characterized GMPs require a bivalent cation for catalysis. In addition to these overall features, the oligomeric state and substrate specificity of GMPs can differ. Bacterial GMP enzymes appear to be mostly dimeric, whereas the eukaryotic enzymes can adopt various oligomeric forms, as exemplified by the active hexameric form of the Leishmania major GMP (6). Oligomerization could affect substrate specificity depending on the association with another regulatory subunit (7).

As a representative of bacterial GMPs, Thermotoga maritima GMP (TmGMP) shows high sequence identity (∼35%) only with eukaryotic GMPs from amoebae, sea anemone, fungi, and the plant Ricinus communis, yet mammalian GMP enzymes consist of α (43 kDa) and β subunits (37 kDa) that share only ∼18% sequence identity with TmGMP, including the conservation of the two signature motifs.

In most cases, GMPs display maximal activity on the physiological substrates, Man1P and GTP. However, puzzling results were obtained with the bifunctional GMPs from Escherichia coli (8) and Pyrococcus furiosus (9), both of which exhibit rather wide substrate tolerance. The P. furiosus GMP-PMI enzyme is unusually promiscuous in that it is able to synthesize with good efficiency up to 17 different NDP-sugars, including various GDP-sugar and NDP-Man products. Similarly, the GMP from Leptospira interrogans, responsible for the infectious disease leptospirosis, shows atypical broad substrate specificity (10). Purified pig liver GMP can accept either Man1P or Glc1P as a sugar moiety, whereas the recombinant β subunit shows high activity for GDP-Man (11).

Although crystal structures of several members of the NDP-sugar pyrophosphorylase superfamily have documented the diversity in combinations of nucleotides and sugar substrates, the molecular determinants responsible for guanosine and mannose specificities have yet to be identified. Here we report the crystal structures, solved in the 2.8–2.1 Å resolution range, of the putative monofunctional GMP from the thermophilic bacterium T. maritima in the absence and presence of bound Man1P, GTP, and GDP-Man ligands. This first characterization of the TM1033 gene product reveals the overall architecture and oligomeric assembly of a GMP member and provides us with a comprehensive view of ligand-free and ligand-bound GMP in the presence of the catalytically important Mg2+. Together with a detailed biochemical characterization of the catalytic activity, structural comparison with other members of the pyrophosphorylase superfamily permits a detailed description of the active site region along with the conformational changes associated with ligand binding. The structural similarities between TmGMP and other homologues from the monofunctional class of GMP and the GMP domain of bifunctional GMPs document the structural determinants responsible for broad substrate specificity and the molecular evolution of monofunctional versus bifunctional GMPs in bacteria.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning, Expression, and Purification

TmGMP, TM1033 (GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase/mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase; UniProt Q9X0C3) was amplified by PCR from T. maritima, strain MSB8, genomic DNA using Pfu Turbo (Stratagene) and primer pairs encoding the predicted 5′- and 3′-ends of TmGMP. The PCR product was cloned into the expression plasmid pMH1, which encodes the purification tag (MGSDKIHHHHHH) preceding the N terminus of full-length TmGMP. DNA sequencing revealed a V261L mutation. Culture conditions providing the highest protein expression level were deduced from an incomplete factorial screen of 16 combinations of four E. coli strains, three culture media, three temperatures, and three concentrations of arabinose inducer (12). E. coli strain Origami (DE3) pLysS cells were grown at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol until A600 reached 0.6. Expression was induced with 0.15% (w/v) arabinose, and the cells were maintained for 6 h at 42 °C. The cells were harvested, and the pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer consisting of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole, 0.25 mg/ml lysozyme, and 1 mm PMSF and stored at −80 °C. Bacterial pellet suspension was thawed and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with 10 μg/ml DNase I and 20 mm MgSO4. After sonication, soluble extract recovered by centrifugation was applied onto a 5-ml Ni2+ chelating column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole. TmGMP was eluted with an imidazole gradient, concentrated by ultrafiltration, and purified by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex-200 (26/60 column; GE Healthcare) in 10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, and 150 mm NaCl. Purified TmGMP was concentrated by ultrafiltration. Protein purity and integrity were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Size Exclusion Chromatography-Multi-angle Laser Light Scattering Characterization

Size exclusion chromatography experiments were carried out on an Alliance 2695 HPLC system (Waters) using a silica gel KW804 column (Shodex). TmGMP was loaded at 3 mg/ml (in 100, 300, or 500 mm NaCl) and 10 mg/ml (in 100 mm NaCl) and eluted with 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.3, and 100, 300, or 500 mm NaCl (flow rate, 0.5 ml/min). Detection was achieved by a triple-angle light scattering detector (Mini-DAWNTM TREOS; Wyatt Technology), a quasi-elastic light scattering instrument (Dynapro; Wyatt Technology), and a differential refractometer (Optilab rEX; Wyatt Technology). Molecular weight and hydrodynamic radius were determined with the ASTRA V software (Wyatt Technology), using a differential index of refraction, dn/dc with a value of 0.175 ml/g.

Crystallization and Data Collection

Small crystals of apo TmGMP were obtained at 20 °C by screening the PACT premier (Molecular Dimensions Ltd.) and MPD suite (Qiagen) crystallization kits using a nanoliter sitting drop setup with automated crystallization Freedom (Tecan) and Honeybee (Cartesian) robots. Larger crystals were grown in hanging drops by mixing equal volumes of protein (20 mg/ml in 10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl) and reservoir (35% (v/v) MPD, 0.1 m phosphate citrate, pH 7.5) solutions. The three TmGMP complexes were formed by incubating the enzyme (12.5 or 25 mg/ml in 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2) with a 16:1 (Man1P) or 8:1 (GTP and GDP-Man) molar excess of ligand for 30 min at room temperature. Crystallization of the TmGMP-Man1P complex was achieved in sitting drops using a protein to well solution ratio of 3:1 and 35% MPD as the well solution. For the TmGMP-GDP-Man complex, sitting drops were set up by mixing equal volumes of the protein solution and well solution made of 30% MPD, 0.1 m sodium acetate, pH 4.6, 20 mm MgCl2. Crystals of the TmGMP GTP complex were obtained in hanging drops with a protein to well solution ratio of 2:1 and 30% MPD, 0.1 m sodium acetate, pH 5.0, 20 mm MgCl2 as the well solution. The crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. The data were collected on ESRF (Grenoble, France) and SOLEIL (Saint-Aubin, France) beamlines, processed with MOSFLM (13) or XDS (14), and scaled and merged with SCALA (15).

Structure Determination and Refinement

The structure of apo TmGMP was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER (16) and the N- and C-terminal domains of Thermus thermophilus GMP (TtGMP; Protein Data Bank accession code 2CU2) separately as search models. A partially refined model was then used as a template to solve the structure of each of the three complexes. The model was manually corrected, and water molecules and ligand(s) were generated with SKETCHER (17) and added with COOT (18). Random sets of reflections were set aside for cross-validation purposes. The models were refined with REFMAC5 (19) using Translation/Libration/Screw (TLS) refinement (three TLS groups) based on group definition proposed by the TLS Motion Determination (TLSMD) server (20). Non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) restraints were applied for refinement of the four structures. The data collection and refinement statistics are reported in Table 1. All of the structures encompass residues 1–333. The C-terminal region 334–336 is disordered and could not be modeled, except for the Man1P complex where residue 334 could be inserted. Peaks above 6 σ in the residual electron density maps were attributed to a bound Mg2+ near each of the three ligands. The stereochemistry of each structure was analyzed with MolProbity (21). The atomic coordinates and structure factors of apo TmGMP and the complexes with Man1P, GTP, and GDP-Man have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (22) (see Table 1 for accession codes). Figs. 12–4 were generated with PyMOL (23). The accessible surface areas were calculated with the PISA server (24), and hinge bending associated with GTP binding was calculated using the Dyndom server (25).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

The numbers in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

| apo | Man1P | GTP | GDP-Man | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| Beamline | ID29 (ESRF) | Proxima1 (SOLEIL) | ID14-EH2 (ESRF) | ID14-EH4 (ESRF) |

| Resolution (Å) | 65.37-2.35 (2.48-2.35) | 65.21-2.10 (2.21-2.10) | 67.57-2.80 (2.95-2.80) | 50-2.70 (2.85-2.70) |

| Space group | P21 | P21 | P21 | C2221 |

| Cell dimension a, b, c (Å) | 64.01, 92.00, 69.69 | 63.93, 91.74, 69.73 | 65.93, 79.57, 70.95 | 84.23, 96.04, 217.12 |

| β (°) | 110.25 | 110.75 | 107.75 | |

| Unique reflections | 31,744 | 43,388 | 17,147 | 24,606 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.2 (96.9) | 98.7 (98.8) | 98.9 (99.1) | 99.8 (99.9) |

| Redundancy | 6.0 (5.4) | 3.1 (3.1) | 3.1 (3.1) | 5.7 (5.8) |

| <I/σI> | 23.5 (2.5) | 17.3 (2.5) | 16 (2.6) | 24.4 (4.2) |

| Rmerge (%)a | 5.5 (47) | 4.3 (47.1) | 6.1 (48) | 5.3 (43.7) |

| No molecules (arbitrary units) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Refinement | ||||

| Rcryst (%)b | 22.4 (36.8) | 18.70 (28.70) | 21.60 (32.10) | 19.11 (24.80) |

| Rfree (%)c | 27.3 (39.2) | 23.01 (31.70) | 26.97 (40.10) | 24.41 (29.80) |

| RMSDd | ||||

| Bond (Å) | 0.01 | 0.013 | 0.01 | 0.013 |

| Angles (°) | 1.154 | 1.335 | 1.218 | 1.457 |

| Number of atoms | ||||

| Proteine | 5365/5416 | 5456/5454 | 5420/5404 | 5421/5420 |

| Water/ions | 48/— | 162/7 | 20/2 | 38/1 |

| Ligands | — | 32 | 64 | 78 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | ||||

| Protein | 76.03 | 50.53 | 75.18 | 64.08 |

| Water/ions | 47.16/— | 38.32/44.45 | 30.61/41.42 | 30.95/26.55 |

| Ligand | — | 49.6 | 56.25 | 42.95 |

| Ramachandran analysis | ||||

| Favored (%) | 97 | 97.6 | 95 | 97.3 |

| Outliers (%) | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Protein Data Bank accession code | 2X5S | 2X65 | 2X60 | 2X5Z |

a Rmerge = Σhkl(Σi|Ihkl-〈Ihkl〉|)/Σhkl|〈Ihkl〉.

b Rcryst = Σhkl||Fo| − |Fc||/Σhkl|Fo|.

c Rfree is calculated for randomly selected reflections excluded from refinement.

d RMSD, root mean square deviation from ideal geometry.

e For each subunit in the dimer.

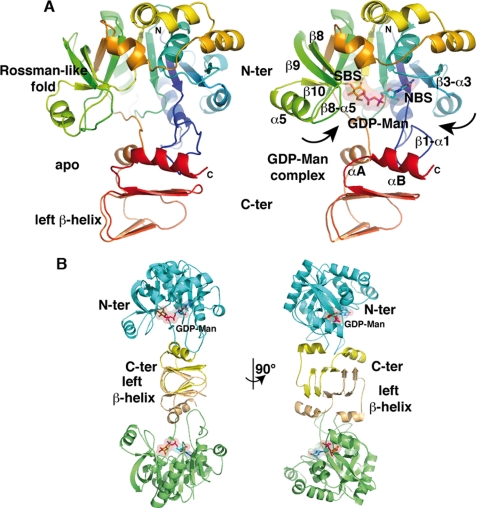

FIGURE 1.

Overall view of a TmGMP subunit and the TmGMP dimer. A, ribbon diagrams of a TmGMP monomer in the apo (left panel) and GDP-Man-bound (right panel) forms viewed down the active site and colored as a rainbow gradient from blue (N-terminal) to red (C-terminal). The nucleotide-binding (NBS) and sugar-binding (SBS) sites are indicated. B, the TmGMP dimer, viewed in two orientations rotated by 90°, is shown with the N- and C-terminal domains colored green/blue and orange/yellow, respectively, for each of the two domains within a subunit. GDP-Man is bound at each active site and is shown through a transparent surface. The GDP-Man is shown with orange carbon, red oxygen, blue nitrogen, and magenta phosphorus atoms.

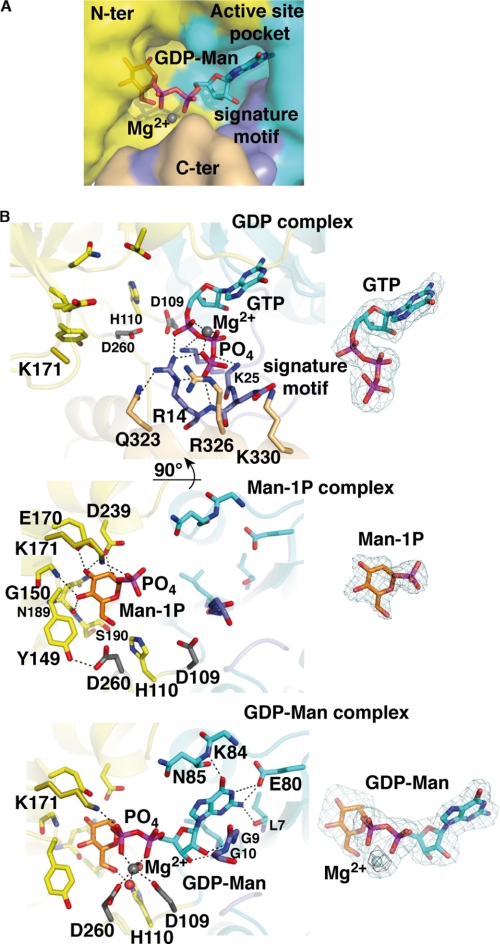

FIGURE 2.

Active site region of TmGMP with bound substrates and product. A, molecular surface of TmGMP, oriented as in Fig. 1, surrounding the active site region with bound GDP-Man and Mg2+ ion (gray sphere) colored as in Fig. 1. The signature motif is shown in purple. B, close-up views of TmGMP with bound GTP, Man1P, and GDP-Man (left panel, top to bottom). The side chains in the nucleotide-binding site and signature motif are shown in cyan and purple, those in the sugar-binding site are in yellow, and those in the C-terminal domain are in orange. The two Asp side chains that coordinate Mg2+ are shown in gray, and the water molecules are red spheres. The corresponding Fo − Fc omit electron density maps (right panel, top to bottom) are contoured at 3.0 σ (cyan) and 5.0 (black).

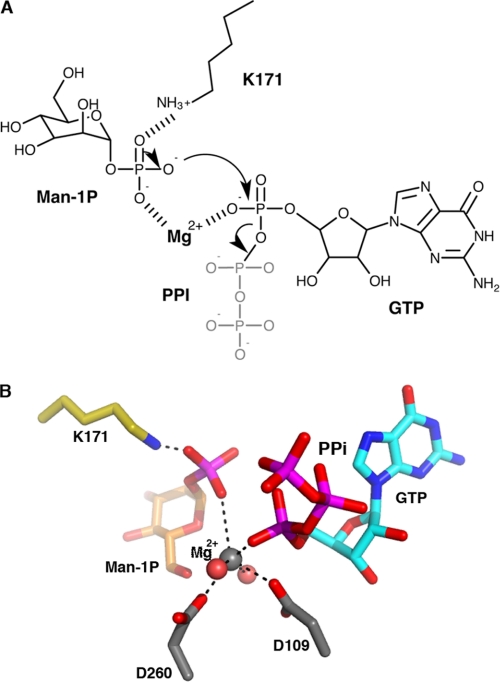

FIGURE 3.

Catalytic mechanism and model of substrate positions in the active site. A, schematic representation of the proposed catalytic mechanism of TmGMP. B, a structure-based model of Man1P- and GTP-bound TmGMP, oriented as in Fig. 1, based on an overlay of the N-terminal domains from the two structures.

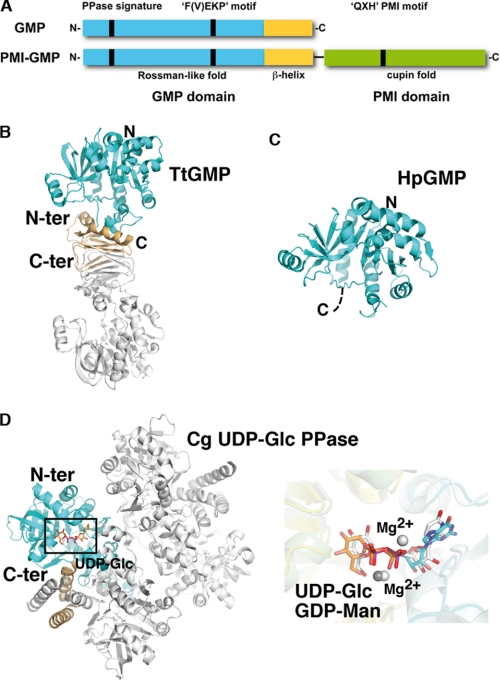

FIGURE 4.

Structural comparison. A, schematic diagram of the molecular organization of monofunctional GMP versus bifunctional GMP/PMI. The positions of the three signature motifs are indicated as vertical bars. B–D, ribbon diagrams of TtGMP (B), the GMP domain of bifunctional PMI-GMP from H. pylori (HpGMP) (C), and UDP-Glc PPase from C. glutamicum, oriented as in Fig. 1 (D, left panel). The GMP domain is colored as in Fig. 2. Close-up overlay (right panel in D) of the active site regions of TmGMP and UDP-Glc PPase with bound ligands. GDP-Man is shown with cyan and orange carbon for the nucleotide and sugar moieties, respectively. UDP-Glc is shown with white carbon. Conservation of the active site topology and near perfect overlap of bound GDP-Man, UDP-Glc, and Mg2+ are evident. C-ter, C-terminal; N-ter, N-terminal.

Enzymatic Assays

Assays were performed at 25 °C on a Cary 50 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Varian) in sample volumes of 250 μl. The activity of TmGMP was recorded in the GDP-Man synthesis direction by measuring the release of inorganic pyrophosphate using the EnzCheck pyrophosphate assay kit (Invitrogen; E-6645). According to the manufacturer's instructions, kinetic measurements were performed in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm MgCl2. Beyond other kit components, the reaction mixture contained a fixed Man1P concentration of 0.5 mm with GTP concentrations ranging from 10 to 500 μm or a fixed GTP concentration of 1 mm with Man1P concentrations ranging from 10 to 200 μm. The reaction was started by the addition of purified GMP to a final concentration of 100 nm, and absorbance at 360 nm was continuously monitored for 5 min. Apparent Km and Vmax values were estimated by linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The same protocol was used to assay the enzyme activity on nonphysiological substrates (Glc1P, Gal1P, and ATP). Optimum catalytic pH and specificity for bivalent cations could not be assessed with the enzyme-coupled assay.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overall View of the Structures

The apo-, Man1P-, GTP-, and GDP-Man-TmGMP structures, refined in the 2.1–2.8 Å resolution range (“Experimental Procedures” and Table 1), show well defined electron densities for most of the protein regions and bound ligands. A TmGMP monomer is made of two separate domains and has overall dimensions of ∼45 × ∼40 × ∼60 Å (Fig. 1). The large N-terminal domain (residues 1–263) folds into a αβα sandwich reminiscent of the dinucleotide-binding Rossman fold. Indeed, it consists of a twisted mixed β-sheet made of seven β-strands arranged in the order 3-2-1-4-6-5-7. The central β-sheet is flanked by eight α-helices tightly packed against the β-sheet. The N-terminal domain comprises an additional subdomain inserted between strands β5 and β6. It is made of a mixed three-stranded β-sheet (β9, β8, and β10) flanked by one of the α-helices (α5) protruding from the Rossmann fold. The distal bent β9 strand is part of both the central β-sheet and the small β9–8-10-sheet.

The C-terminal domain (residues 264–334) is composed of an α-helix (αA), followed by a short left-handed β-helix and folds back toward helix αA by forming a second α-helix (αB). The β-helix is made of five β-strands (βA–E) with strands βA–D arranged in two regular coils, whereas strand βE is forced in an antiparallel association with βD by a β-hairpin (Fig. 1). Helices αA and αB, together with the β-hairpin of the β-helix, establish extensive interactions with a loop inserted between strand β1 and helix α1 of the N-terminal domain and contribute to the stabilization of the relative orientation of the two domains.

Dimeric Assembly

Size exclusion chromatography shows that TmGMP behaves predominantly as a dimer in solution, consistent with the oligomeric assembly observed for most bacterial GMPs. Further analysis was performed at various ionic strengths using multi-angle light scattering with a refractive index detector. In all cases, multi-angle light scattering measurement yielded a molecular mass of 80 kDa (5% experimental error) for TmGMP, with a polydispersity of 1.01, in agreement with a dimeric assembly, stable even at high salt concentrations (data not shown).

Each of the four structures shows two molecules tightly packed as a dimer within the asymmetric unit (Fig. 1). The dimer interface is formed by a parallel tail-to-tail arrangement of the left-handed β-helices from each monomer, as previously observed for the ADP-Glc PPase from potato tuber (7) and Agrobacterium tumefaciens (26). This tight arrangement results in an elongated and continuous β-helix structure central to the dimeric assembly. A total surface of ∼2700 Å2 is buried to a 1.4-Å probe radius at the interface. In addition to contacts mediated by the β-helix complementation, the dimeric assembly is stabilized through numerous hydrophobic contacts involving residues from the β-helix and from the C-terminal helix αB of each monomer. Among the 36 residues involved in the dimer interface, 16 establish apolar contacts consistent with the low salt sensitivity of the dimer observed in solution. Sequence alignment analysis of bacterial GMP reveals that residues of the dimer interface are not strictly conserved but share a similar hydrophobic character (supplemental Fig. S1).

Active Site

The structures of the GTP-, Man1P-, and GDP-Man-TmGMP complexes allow us to decipher the mode of binding of substrate/product and identify key residues responsible for catalysis. Substrate/product-bound TmGMP clearly evidences a closed and well ordered active site occupied by the bound ligand. The active center lies in a deep pocket located in the N-terminal domain (Fig. 2). The base of the pocket is delimited by the central β-sheet, whereas the side walls are shaped by two flexible loops, β1-α1 and β3-α3, on one side and the three-stranded β-sheet (β9–8-10) on the other side for recognition of the nucleotide and the sugar moiety, respectively. The two active sites of the dimer are located on opposite faces and are ∼55 Å apart.

Comparative analysis of the structures of TmGMP bound to each of the two substrates, GTP and Man1P, and the end product GDP-Man reveals that the structure of the GDP-Man complex illustrates most interactions responsible for substrate binding, especially at the nucleotide- and sugar-binding sites. The guanidine moiety is sandwiched between loop β1-α1, which contains the canonical signature motif GGXGXR(L)XPLX5PK of GMPs (5), and loop β3-α3 (Fig. 2). Selective recognition of the guanidine purine ring is achieved by interactions of the exocyclic amino group with the main chain carbonyl group of Val56 and the carboxyl moiety of Glu80 and by interactions of the guanidine carbonyl with the main chain nitrogen atoms of Lys84 and Asn85. The O2, O3, and O4 hydroxyls of the sugar moiety interact with residues that emerge from the β9–8-10-sheet and helix α9 and are strictly conserved within bacterial GMPs. The O6 hydroxyl is coordinated by the conserved His110 and Asp260 (Fig. 2). Polar contacts involved in the anchoring of GTP, Man1P, and GDP-Man are summarized in supplemental Table SI.

Major differences occur in the mode of binding of the phosphate backbone between the GTP- and GDP-Man complexes. In the GDP-Man complex, the phosphate groups span the active site, where they interact with the two conserved Asp109 and Asp260 side chains through a Mg2+. Two water molecules complete the octahedral coordination geometry characteristic of Mg2+ (Fig. 2). In the GTP complex the phosphate groups point away from the sugar-binding site, and the β- and γ-phosphates, which constitute the leaving pyrophosphate entity, are anchored within a groove where they interact with the main chain nitrogen atoms of residues Gly12, Glu13, and Arg14 of the signature motif (Fig. 2). The solvent-exposed α-phosphate is in contact with the invariant Arg14 and Lys25.

Insights into Substrate Binding and Catalysis

The PPase activity is characterized by a sequential order of binding of substrates and relies on accurate positioning and direct reactivity between the two substrates more than on strictly catalytic residues (27). Indeed, PPase activity was shown to depend critically on the presence of a divalent cation, mostly Mg2+, that counterbalances the negative charges of the phosphate groups in the active site and provides bridging interactions between these two polar moieties of opposite charges (27). In most characterized PPases, the reaction proceeds via a sequential ordered bi-bi mechanism with NTP binding prior to sugar-1P binding (28). Once both substrates are bound, the phosphate group of the sugar attacks on one side of the α-phosphate of NTP to form a NDP-sugar, with the concomitant breaking of the phosphodiester bond on the opposite face to release pyrophosphate (Fig. 3). The reaction can also proceed via a ping-pong mechanism that requires formation of a covalent NMP-enzyme intermediate, so far described only for Salmonella dTDP-Glc PPase (29). Comparative analysis of the structures of apo TmGMP and its GTP complex reveals that GTP binding is associated with large conformational changes of loop regions surrounding the active site, along with side chain reorientations (Fig. 1). In the nucleotide-binding site, the β1-α1 loop is displaced by 1.5 Å to favor interactions with the β- and γ-phosphates of GTP. The C-terminal domain rotates by ∼10° toward the N-terminal domain as to push helix αA toward the nucleotide-binding site. This event allows Arg326 in helix αB to establish long range interaction with the distal γ-phosphate (Fig. 2). A di-acid bridge is formed between the conserved Asp109 and Asp260 side chains, the latter residue being located in the hinge region between the N- and C-terminal domain. The nearby imidazole ring of His110 is flipped to establish a hydrogen bond with the main chain carbonyl of Ser190, thus rigidifying the sugar-binding site.

Upon Man1P binding, the β9–8-10-α5 subdomain rotates by 10° toward Man1P, which results in the global closure of the sugar-binding site and restraint active site accessibility (Fig. 2). The side chain of the conserved Lys171 in the β8-α5 loop, which is part of a flexible region poorly defined in the structures of apo TmGMP and its GTP complex, is displaced by ∼5 Å to contact the phosphate group of Man1P. In the absence of Mg2+, the side chain of Asp260 is rotated by 90° to interact with the Tyr149 phenol.

Although the exact mechanism used by TmGMP to catalyze GDP-Man formation is still unknown, our structural study suggests that TmGMP follows a sequential mechanism. Neither GTP nor GDP-Man are involved in a covalent NMP-enzyme intermediate in the respective complex structures, as would be expected in the case of a ping-pong mechanism. Moreover, rearrangements that occur upon GTP and Man1P binding argue for a sequential binding of substrates, with GTP binding prior to Man1P. Indeed, anterior Man1P binding would create steric constraints preventing subsequent GTP binding. Conversely, the overall conformation of the active site in the GTP complex does not prevent and could even promote subsequent binding events of Man1P and Mg2+ (Fig. 3). Alternatively, Mg2+ could bind first to a TmGMP-GTP intermediate binary complex to favor binding of the sugar-1P moiety that in turn could trigger Mg2+ binding in a high affinity mode. Once a quaternary GMP-GTP-Man1P-Mg2+complex is formed, the system becomes competent for catalysis. The Mg2+ prevents electrostatic repulsion between the phosphate groups of the two substrates, whereas Lys171 stabilizes the phosphate group of Man1P and increases the nucleophilicity of the oxygen atom responsible for attack on the Pα of GTP.

Kinetic analysis of TmGMP activity using the physiological Man1P and GTP substrates yielded Km values in the micromolar range, consistent with those obtained with mono- or bifunctional GMPs from other bacterial species (Table 2). Because most bacterial GMPs exhibit greater affinity for Man1P than for GTP, GTP binding could represent the limiting step for catalysis.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of GMP from various bacterial sources

| Man1P | GTP | |

|---|---|---|

| Arthrobacter (2)a | 35 | 130 |

| P. aeruginosa (3) | 8.2 | 41 |

| S. enterica (41) | 15 | 40 |

| M. smegmatis (42) | 168 | 113 |

| H. pylori (38) | 22 | NDc |

| P. furiosus (9) | 72 | ND |

| L. interrogans (10) | 63 | 236 |

| T. maritimab | 12.8 | 63.7 |

a The numbers in parentheses are reference numbers.

b This study.

c ND, not determined.

Structural Comparison with Other Pyrophosphorylases

Despite low sequence similarity among NDP-sugar PPases, they share a similar domain organization and common structural features. This class of enzymes is dominated by conservation of the Rossman-like fold in the N-terminal domain. In contrast, the C-terminal domain presents significant variations (Fig. 4). Although a left-handed β-helix structure frequently occurs in PPases, e.g. UDP-GlcNAc (N-acetyl-d-glucosamine-1-phosphate acetyltransferase) (30) or ADP-Glc PPase (7), an unrelated structural fold of unknown function has also been observed in the structures of dTDP-Glc PPase (RmlA) (31) and mammalian UDP-GlcNAc PPase (AGX1/2) (32). In some enzymes the C-terminal domain holds a second enzymatic activity in addition to the nucleotidyltransferase activity, as seen for some bifunctional GMPs (PMI) and UDP-GlcNAc PPases, which exhibit phosphomannose isomerase and acetyltransferase activity, respectively (33, 34). The C-terminal domain can also regulate the PPase activity by mediating enzyme oligomerization (6) and/or by binding allosteric regulators (7).

Searches for structural homologues using the DALI server (35) revealed that the structures most closely related to TmGMP are those of the Helicobacter pylori (Protein Data Bank accession code 2QH5) and T. thermophilus GMPs (Protein Data Bank accession code 2CU2), that belong to the class of bifunctional PMI-GMPs and monofunctional GMPs, respectively. In these enzymes, the N-terminal domain adopts a similar Rossman-like fold with numerous small variations in loop regions flanking the active center (Fig. 4). In the case of the H. pylori GMP, HpGMP, the β9 strand is shorter than the one from TmGMP and is therefore not associated to the central β-sheet that comprises two additional β-strands upstream β1, supporting a higher flexibility of the sugar binding region. Whereas the N-terminal domain of T. thermophilus apo GMP, TtGMP, closely resembles that of apo TmGMP, the overall conformation of the active site in apo HpGMP is surprisingly most similar to that of the closed form of the TmGMP-Man1P complex. Despite a flexible β1-α1 loop that argues for a conformational state reflecting that of an apo enzyme, the closed conformation of the active site of HpGMP in the absence of substrates could be artificially influenced by the crystal packing environment or may reflect the dynamic behavior of this class of enzymes, because conformational flexibility appears to be a hallmark of PPase function.

The structure of the C-terminal domain is conserved in TtGMP and is responsible for the dimeric assembly via β-helix complementation similar to TmGMP (Fig. 4). In contrast, the role of the C-terminal domain of the bifunctional PMI/GMP could not be deciphered from the HpGMP structure solved from a variant lacking the C-terminal domain.

Beside the structures of GMP members, the structure most closely related to that of TmGMP is that of UDPGlc PPase from Corynebacterium glutamicum (CgUGP) (36, 37). Most of the structural elements of CgUGP are similar to those of TmGMP, except that the CgUGP structure lacks TmGMP helices α7 and α8 and comprises two additional helices inserted in the α2-β3 loop. The C-terminal domain of CgUGP is made of a helix-loop-helix motif that, conjointly with the two additional helices, is responsible for dimer formation (Fig. 4). Comparative analysis of the CgUGP and TmGMP active sites reveals major differences related to the specific anchoring of their respective substrates, even if the global architecture is conserved. The nucleotide-binding site of CgUGP selectively filters pyrimidine bases by steric constraints that prevent accommodation of purine bases. Specific recognition of a glucose moiety by the CgUGP active site is achieved through with the presence of the small Thr242 side chain (equivalent to TmGMP Asp239). Moreover, the side chain conformation of Leu140 and Tyr218 imposes steric constraints incompatible with the binding of a mannose moiety with an O2 hydroxyl in axial configuration. In GMPs, these two residues correspond to a Pro or Ala (Pro107 in TmGMP) and a conserved Phe (Phe193 in TmGMP), respectively.

Structural Basis of the GMP Activity in Bifunctional Enzymes

The kinetic parameters of T. maritima and H. pylori GMP versus Man1P and GTP substrates are very similar, consistent with the structural conservation of residues involved in substrate binding and catalysis (Table 2). This suggests that the GMP-catalyzed reaction requires a specific active site architecture and proceeds similarly for mono- and bifunctional GMPs. Moreover, the two separate catalytic domains of bifunctional PMI/GMP can communicate to modulate their catalytic activities, as exemplified by the H. pylori enzyme, where GDP-Man binding to the GMP domain decreases the PMI domain affinity for Fru6P. Conversely, Man6P binding to the PMI domain seems to affect GDP-Man binding to the GMP domain (38). Furthermore, the bifunctional GMP/PMI P. aeruginosa PslB, harboring inactive mutations for PMI activity, conserves an unaltered GMP activity (39). Most importantly, a truncated form of the P. furiosus bifunctional PMI/GMP lacking the PMI domain has very weak GMP activity, whereas its affinity for Man1P is unaltered. Compared with full-length P. furiosus PMI/GMP, the truncated enzyme no longer displays broad substrate tolerance (9). This is consistent with our findings showing the implication of the TmGMP C-terminal domain in substrate coordination. Indeed, the conserved Arg326 in monofunctional GMPs participates in GTP γ-phosphate coordination and corresponds to a conserved Lys residue in bifunctional PMI/GMP that could play a similar role.

The PMI and GMP activities of the bifunctional P. aeruginosa enzyme were strongly reduced upon mutation of Ser12 (equivalent to Glu13 in TmGMP) to Ala, whereas affinities for the two Man1P and GTP substrates were not affected (3). In TmGMP, Glu13 belongs to the signature motif, and its side chain participates in the domain interface, whereas the main chain amino group coordinates the GTP γ-phosphate. Mutation of this residue is not expected to affect GTP binding, but it could affect domain stabilization that supports cross-talk between the two separate domains for efficient catalysis. This would be consistent with our findings showing that GTP binding to TmGMP is associated with a rigid body movement of the C-terminal domain in concert with rearrangements of loop regions harboring the two Asp residues required for Mg2+ binding. Because hinge movement in the relative orientation of the two TmGMP domains favors Mg2+ binding, a truncated bifunctional GMP lacking the C-terminal domain would require both substrates to be tightly bound into the active site to allow Mg2+ to bind to the enzyme, whereas a partial coordination of the bivalent ion would significantly decrease the reaction rate.

Substrate Specificity and Implications for NDP-Sugar Biosynthesis

Kinetics experiments on TmGMP using ATP instead of GTP revealed no detectable PPase activity. Among the sugar-1P assayed (Glc1P and Gal1P), only the use of Glc1P in place of Man1P led to the detection of some residual GDP-Glc PPase activity, but this activity was too low to be accurately measured (Table 3). This argues for an exquisite specificity of TmGMP toward GTP and Man1P. Indeed, the adenine base of ATP lacks the exocyclic amino group of GTP that significantly contributes to nucleotide binding. Similarly, the amino group of ATP, compared with the guanine exocyclic oxygen atom, seems less favorable to interact with the main chain nitrogen of Asn85. The low activity detected for Glc1P is consistent with our structural data, because only a small movement of the Asp239 side chain seems sufficient to accommodate the equatorial conformation of the O2 hydroxyl. Binding of Gal1P into the TmGMP active site is unlikely, because this would require drastic conformational changes of the backbone region near Asn189, consistent with the absence of enzymatic activity observed when using Gal1P instead of Man1P.

TABLE 3.

Substrates assayed for enzymatic activity of TmGMP

+, activity measurable (see Table 2); −, activity not detectable; +/−, activity detectable but not measurable.

| Sugar-1-phosphate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Man1P | Glc1P | Gal1P | |

| NTP + GTP | + | +/− | − |

| NTP + ATP | − | − | − |

Tolerance for Glc1P binding was also reported for E. coli GMP (8). Similarly, the closely related GMP from L. interrogans shows atypical broad substrate specificity with synthesis of GDP-Man, IDP-Man, UDP-Man, and ADP-Glc (10). Sequence comparison reveals that subtle mutations in the nucleotide- and sugar-binding sites, e.g. TmGMP A89I/V56G and H110A, could contribute to this relaxed substrate specificity (supplemental Fig. S1). However, the question remains open on how the E. coli and P. furiosus bifunctional PMI/GMP acquired their very broad substrate specificity. The architecture of the active site of the GMP domain in mono- and bifunctional GMPs is very similar, with strict conservation of key functional residues in the nucleotide- and sugar-binding sites (supplemental Fig. S1). It is likely that the addition of a PMI domain extends the overall flexibility to the GMP domain to confer such a relaxed substrate specificity, consistent with the restricted GTP and Man1P catalytic activity of the P. furiosus bifunctional PMI/GMP lacking the PMI domain (9). Further structural analysis of a member of the bifunctional class of GMP is required to clarify possible cross-talk between the pyrophosphorylase and isomerase activities. In turn, the natural broad substrate specificity of the P. furiosus bifunctional PMI/GMP has been successfully exploited to generate a library of purine-containing sugar nucleotides (9). When coupled to glycan libraries in conjunction with downstream glycosyltransferases, PPases can be employed to generate NDP-sugar libraries for synthesis of a large variety of glycosylated compounds using a chemoenzymatic strategy called natural product glycorandomization (40).

In summary, the structures of TmGMP in the apo form and as three complexes with Man1P, GTP, and GDP-Man provide a comprehensive view of the monofunctional class of bacterial GMPs and document the key catalytic role of the Mg2+ cofactor and the requirement of both domains for catalysis. Comparison with other PPases reveals subtle structural adaptations within the Rossman-like domain for recognition of GTP and Man1P. This study provides a novel template to understand the basis of nucleotide and sugar substrate selectivity among the mono- versus bifunctional classes of GMPs, as a premise for the design of novel PPase inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Abraham Saliba for contribution to initial experiments, Gerlind Sulzenbacher for helpful discussion, Giuliano Sciara and Stephanie Blangy for size exclusion chromatography-multi-angle light scattering experiments, Maria Luz Cardenas and Athel Cornish-Bowden for advice in enzyme kinetics, and Bruno Coutard and Pascale Marchot for critical reading of the manuscript. We acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility and the Synchrotron Soleil for provision of beam time, and we thank ESRF and Soleil staff for assistance in using the beamlines.

This work was supported in part by funds from the CNRS and the Fondation de la Recherche Médicale (to Y. B.) and Grant U54GM074961 from the National Institutes of Health (to P. K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table SI and Fig. S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 2X5S, 2X65, 2X60, and 2X5Z) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- NDP-sugar

- nucleoside-5′-diphosphosugars

- TmGMP

- GMP from the thermophylic bacterium T. maritima

- Man1P

- mannose-1-phosphate

- PMI

- phosphomannose isomerase

- PPase

- pyrophosphorylase

- CgUGP

- C. glutamicum UDPGlc PPase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vanfossen A. L., Lewis D. L., Nichols J. D., Kelly R. M. (2008) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1125, 322–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preiss J., Wood E. (1964) J. Biol. Chem. 239, 3119–3126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.May T. B., Shinabarger D., Boyd A., Chakrabarty A. M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 4872–4877 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen S. O., Reeves P. R. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1382, 5–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sousa S. A., Moreira L. M., Leitão J. H. (2008) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 80, 1015–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perugini M. A., Griffin M. D., Smith B. J., Webb L. E., Davis A. J., Handman E., Gerrard J. A. (2005) Eur. Biophys. J. 34, 469–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin X., Ballicora M. A., Preiss J., Geiger J. H. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 694–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y. H., Kang Y. B., Lee K. W., Lee T. H., Park S. S., Hwang B. Y., Kim B. G. (2005) J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 37, 1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizanur R. M., Pohl N. L. (2009) Org. Biomol. Chem. 7, 2135–2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asención Diez M. D., Demonte A., Giacomelli J., Garay S., Rodrígues D., Hofmann B., Hecht H. J., Guerrero S. A., Iglesias A. A. (2010) Arch. Microbiol. 192, 103–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ning B., Elbein A. D. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 6866–6874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abergel C., Coutard B., Byrne D., Chenivesse S., Claude J. B., Deregnaucourt C., Fricaux T., Gianesini-Boutreux C., Jeudy S., Lebrun R., Maza C., Notredame C., Poirot O., Suhre K., Varagnol M., Claverie J. M. (2003) J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 4, 141–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leslie A. G. W. (1992) Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography 26, Daresbury Laboratory, Warrington, UK [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabsch W. (1988) J. Appl. Cryst. 21, 916–924 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans P. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CCP4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Painter J., Merritt E. A. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 439–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis I. W., Leaver-Fay A., Chen V. B., Block J. N., Kapral G. J., Wang X., Murray L. W., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Snoeyink J., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2007) 35, W375–W383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berman H. M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T. N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I. N., Bourne P. E. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, Palo Alto, CA [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krissinel E., Henrick K. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayward S., Berendsen H. J. (1998) Proteins 30, 144–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cupp-Vickery J. R., Igarashi R. Y., Perez M., Poland M., Meyer C. R. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 4439–4451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuccotti S., Zanardi D., Rosano C., Sturla L., Tonetti M., Bolognesi M. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 313, 831–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paule M. R., Preiss J. (1971) J. Biol. Chem. 246, 4602–4609 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindquist L., Kaiser R., Reeves P. R., Lindberg A. A. (1993) Eur. J. Biochem. 211, 763–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sulzenbacher G., Gal L., Peneff C., Fassy F., Bourne Y. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11844–11851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blankenfeldt W., Asuncion M., Lam J. S., Naismith J. H. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 6652–6663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peneff C., Ferrari P., Charrier V., Taburet Y., Monnier C., Zamboni V., Winter J., Harnois M., Fassy F., Bourne Y. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 6191–6202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shinabarger D., Berry A., May T. B., Rothmel R., Fialho A., Chakrabarty A. M. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 2080–2088 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mengin-Lecreulx D., van Heijenoort J. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 6150–6157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holm L., Sander C. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 233, 123–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thoden J. B., Holden H. M. (2007) Protein Sci. 16, 432–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thoden J. B., Holden H. M. (2007) Protein Sci. 16, 1379–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu B., Zhang Y., Zheng R., Guo C., Wang P. G. (2002) FEBS Lett. 519, 87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee H. J., Chang H. Y., Venkatesan N., Peng H. L. (2008) FEBS Lett. 582, 3479–3483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J., Hoffmeister D., Liu L., Fu X., Thorson J. S. (2004) Bioorg. Med. Chem 12, 1577–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fey S., Elling L., Kragl U. (1997) Carbohydr. Res. 305, 475–481 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ning B., Elbein A. D. (1999) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 362, 339–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.