Abstract

Objective

There are few data on whether prior fundoplication has an impact on subsequent esophageal resection and reconstruction. The aim of this study is to review our experience with patients undergoing esophagectomy after previous fundoplication.

Methods

Medical records were reviewed of all patients undergoing esophageal resection from 1988 to 2008 at the Mayo Clinic. Patients with a fundoplication before esophagectomy were compared with a matched control group who had esophagectomy alone.

Results

There were 2313 esophageal resections, and 80 patients had undergone at least 1 previous anti-reflux surgery. Indications for esophagectomy were benign stricture/perforation in 41 patients, cancer in 28 patients, and dysplasia in 11 patients. The surgical approach was Ivor Lewis in 38 patients, left thoracoabdominal in 29 patients, transhiatal in 10 patients, and McKeown in 3 patients. The conduit used was stomach in 70 patients, jejunum in 6 patients, and colon in 3 patients; 1 patient had a diversion and cervical esophagostomy only. Operative mortality occurred in 3 patients (3.7%). Postoperative complications occurred in 50 patients (62.5%), including anastomotic leak in 17 (21.5%). Sixteen patients (20%) required reoperation for complications. Complication, anastomotic leak, and reoperation rates were significantly higher in patients with anti-reflux surgery before esophagectomy compared with matched controls.

Conclusion

Esophagectomy after prior anti-reflux surgery is challenging, but the stomach is usually a suitable conduit for esophageal replacement. Patients with a history of anti-reflux surgery who undergo esophagectomy are at significantly increased risk for postoperative complications, anastomotic leak, and need for reoperation.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common chronic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, affecting approximately 19 million people in the United States.1 The introduction of laparoscopic fundoplication in 1991 made surgical therapy for GERD a more attractive option for both patients and referring physicians.2 Unfortunately, some anti-reflux procedures fail, and recurrent reflux symptoms, disabling dysphagia, gas bloat syndrome, anatomic recurrence of hiatal hernia, or other complications of the operation develop. Long-term failure rates as high as 25% have been reported.3,4 In several large series of anti-reflux operations, 6% to 15% of patients require reoperation.5,6 A repeat anti-reflux procedure may be associated with a higher expected failure rate than the primary operation, and occasionally esophageal resection may be the preferred ultimate treatment option.6–8

Reoperative esophageal surgery can be technically challenging. Gastric anatomy can be severely distorted by scarring or by herniation of the fundus into the chest. Furthermore, the stomach may not be suitable for esophageal reconstruction because of damage from prior esophagogastric operations. There are little data on whether prior surgery on the esophagogastric junction has an impact on the outcomes of subsequent esophageal resection and reconstruction. We hypothesized that esophagectomy after anti-reflux surgery was associated with a significantly increased risk of postoperative complications. The aim of this study is to test this hypothesis by comparing short- and long-term outcomes of patients with a fundoplication before esophagectomy with a matched control group who had esophagectomy alone.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Selection and Study Design

All patients who underwent esophageal resection at the Mayo Clinic between January 1, 1988, and December 31, 2008, were identified from a prospectively maintained surgical database. Anti-reflux procedures had been performed at Mayo Clinic Rochester, Minnesota, as well as other institutions, but all esophageal resections were performed at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. The techniques used for esophagogastrectomy have been described by us and included Ivor Lewis, transhiatal, extended esophagectomy (McKeown), and left thoracoabdominal approach.9–12 The American Joint Committee for Cancer Staging TNM classification was used to stage the cancer.13 The medical records were reviewed for demographic information, presenting symptoms, operative procedures, prior surgery, pathology, morbidity and mortality, length of hospitalization, and last follow-up visit or date of death. Operative mortality included all deaths occurring within 30 days of the operative procedure and those who died later but during the same hospitalization. Survival data not available in the medical record were obtained from the Social Security Death Index. Follow-up by chart review and with the primary care physician was performed. The date of esophagectomy was the starting point in the survival estimation and the date of death or last follow-up the end point. The Mayo Foundation Institutional Review Board approved this study with waiver of informed consent and waiver of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

To assess the impact that previous anti-reflux surgery had on outcomes after esophagectomy, a control group was created using frequency matching. All patients who had undergone anti-reflux surgery before an esophagectomy in the timeframe of interest were included as cases. Patients were categorized by gender, age (<60 years, >60 years), surgical era (1988–1997, 1998–2008), and diagnosis (benign or Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia; cancer), resulting in 8 possible combinations of the matching criteria. The number of cases having each combination was identified. The 2233 patients who had undergone esophageal resection without prior anti-reflux surgery from January 1, 1988, to December 31, 2008, at Mayo Clinic Rochester, Minnesota, comprised the list of potential controls. Potential control lists were sorted in a random order and reviewed in sequence until the required number of controls met criteria for inclusion. Twice as many controls as cases (2:1 matching) were selected for each of the 8 combinations.

Gender and age were selected as matching criteria because in a recent analysis of 162 patients undergoing esophagectomy for locally advanced esophageal cancer at the Mayo Clinic, we found that age less than 60 years and female gender were significantly associated with improved survival.14 Matching on diagnosis was also important in creating a well-matched control group because we also previously showed that the technical difficulties in patients who undergo esophageal resection for benign disease are greater than in those who undergo resection for malignancy.7 Symptoms of benign disease often have been present for years before esophagectomy, and most of these patients have undergone prior therapeutic procedures. The surgical era was selected as a matching criteria to account for some of the changes in surgical technique during the study time period at the Mayo Clinic. Whereas a hand-sewn anastomotic technique was used predominantly in the earlier surgical era (1988–1997), a linear stapled anastomotic technique was used more frequently in the later era (1998–2008). In addition, most of the patients in the earlier era had undergone anti-reflux surgery via an open laparotomy or thoracotomy approach, whereas a laparoscopic anti-reflux operation was more common among the patients in the latter era.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for categoric variables are reported as frequency and percentage, and continuous variables are reported as mean (standard deviation) or median (range) as appropriate. For categoric variables, comparisons between groups were made using chi-square or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared by the Student t test. All statistical tests were 2-sided. Univariate logistic regression, assessing covariates of clinical interest and the association of case/control status with outcomes, was performed to determine factors associated with increased rates of postoperative complications, anastomotic leak, need for reoperation, and death after esophagectomy. Factors analyzed included age, gender, time period esophagectomy was performed, diagnosis, cancer stage, history of induction chemoradiation therapy, operative time, surgical approach used for esophagectomy, type of conduit used for esophageal reconstruction (stomach vs colon/small intestine), location of the anastomosis, and history of anti-reflux surgery. Univariate analysis of the cases only was also performed to determine additional factors associated with increased risk of postoperative complications, anastomotic leak, need for reoperation, and development of anastomotic stricture requiring dilation. In addition to the factors analyzed for cases and controls, the number of previous anti-reflux operations, the length of time between anti-reflux operation and esophagectomy, the type of anti-reflux operation performed, the surgical approach used for the anti-reflux operation, whether a gastroplasty to lengthen the esophagus had been performed, whether the patient had complications after anti-reflux surgery, and the anastomotic technique used for esophageal reconstruction were also analyzed. Variables considered in the multiple variable models were those with a P value of .30 or less in the univariate assessments. Final models used backward model selection, although for each outcome, forward selection and a stepwise procedure confirmed the same model. Multiple variable models were not fit for the outcomes of leak, reoperation, and stricture when assessing only the 80 cases because of the paucity of events (n = 17, 16, and 19, respectively). For the outcome of time to patient death, univariate Cox proportional hazards models were constructed, assessing clinically interesting covariates and case/control status. Long-term survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier survival method. SAS v9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Patient Characteristics

During the study time period, 2313 esophageal resections were performed at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, and 80 patients (3.4%) had undergone previous anti-reflux surgery before esophagectomy (Table 1). Characteristics of the 80 cases and 160 matched controls are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics and operative details of 80 patients who underwent anti-reflux surgery before esophagectomy

| Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Interval between anti-reflux operation and esophagectomy | 43.4 mo | 1 d to 33.2 y |

| No. | % | |

| Indication for anti-reflux operation | ||

| Paraesophageal/hiatal hernia | 22 | 27.5 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 58 | 72.5 |

| Prior esophageal lengthening procedure | ||

| Wedge gastroplasty | 13 | 16.3 |

| Fundoplication only | 67 | 83.7 |

| No. of prior anti-reflux operations | ||

| 1 | 52 | 65 |

| 2 | 24 | 30 |

| 3 | 3 | 3.8 |

| 4 | 1 | 1.2 |

| Total | 113 | |

| Anti-reflux operations performed | ||

| Nissen | 84 | 74% |

| Belsey | 14 | 12% |

| Collis–Nissen | 6 | 5% |

| Toupet | 4 | 4% |

| Hill | 3 | 3% |

| Collis–Belsey | 2 | 2% |

| Total | 113 | 100% |

| Surgical approach used for anti-reflux operation | ||

| Open transabdominal | 48 | 42% |

| Open transthoracic | 40 | 35% |

| Laparoscopic | 25 | 22% |

| Total | 113 | 100% |

| Complications after anti-reflux surgery | ||

| Leak | 19 | 23.4% |

| Dysphagia | 11 | 13.4% |

| Stricture | 4 | 5% |

| Mesh eroded into esophagus | 4 | 5% |

| Some patients had>1 complication | ||

| Anastomotic technique for esophageal reconstruction | ||

| Hand-sewn | 63 | 78.7 |

| Mechanical stapler | 16 | 20.0 |

| No anastomosis done | 1 | 1.3 |

TABLE 2.

Comparison of variables between patients undergoing esophagectomy who had a previous anti-reflux operation and a frequency-matched control group with no history of anti-reflux surgery

| Previous anti-reflux surgery | No previous anti-reflux surgery | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 80 | 160 | |

| Median age, y | 63 | 62 | .36 |

| Range | 19–92 | 0.8–95 | |

| Gender | 1.0 | ||

| Male | 46 (57.5%) | 92 (57.5%) | |

| Female | 34 (42.5%) | 68 (42.5%) | |

| Era esophagectomy performed | 1.0 | ||

| 1988–1997 | 27 (33.7%) | 54 (33.7%) | |

| 1998–2008 | 53 (66.3%) | 106 (66.3%) | |

| Indication for esophagectomy | .98 | ||

| Benign | 41 (51.2%) | 81 (50.6%) | |

| Cancer | 28 (35%) | 58 (36.3%) | |

| HGD | 11 (13.8%) | 21 (13.1%) | |

| Surgical approach for esophagectomy | <.001 | ||

| Ivor Lewis | 38 (47.5%) | 79 (49.4%) | |

| L TAB | 29 (26.2%) | 14 (8.7%) | |

| THE | 10 (12.5%) | 54 (33.8%) | |

| McKeown | 3 (3.8%) | 13 (8.1%) | |

| Surgical approach when esophagectomy done for benign disease | <.001 | ||

| Ivor Lewis | 13 (31.7%) | 30 (37.5%) | |

| L TAB | 22 (53.7%) | 13 (16.2%) | |

| THE | 5 (12.2%) | 32 (40.0%) | |

| McKeown | 1 (2.4%) | 5 (6.3%) | |

| Surgical approach when esophagectomy done for malignancy | .003 | ||

| Ivor Lewis | 25 (64.1%) | 49 (61.2%) | |

| L TAB | 7 (17.9%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| THE | 5 (12.8%) | 22 (27.5%) | |

| McKeown | 2 (5.1%) | 8 (10%) | |

| Conduit used | .23 | ||

| Stomach | 70 (87.5%) | 145 (90.6%) | |

| Jejunum | 6 (7.5%) | 5 (3.1%) | |

| Colon | 3 (3.8%) | 10 (6.3%) | |

| Jejunostomy tube | .22 | ||

| Yes | 35 (43.8%) | 80 (50%) | |

| No | 45 (56.2%) | 80 (50%) | |

| Operative time (min) | 360 | 344.5 | .31 |

| Anastomosis location | <.001 | ||

| Right chest | 38 (47.5%) | 79 (49.4%) | |

| Left chest | 29 (36.2%) | 14 (8.8%) | |

| Left neck | 12 (15%) | 67 (41.8%) | |

| Length of stay, d | 21.3+4.3 | 14.1+.1 | <.001 |

| Range | 7–165 | 0–56 | |

| Postoperative complication | 50 (62.5%) | 59 (36.9%) | <.001 |

| Anastomotic leak | 17 (21.5%) | 17 (10.6%) | .03 |

| Need for reoperation | 16 (20%) | 14 (8.7%) | .03 |

| Operative mortality | 3 (3.7%) | 1 (0.6%) | .07 |

| Follow-up (mo) | 38.2 | 37.9 | .22 |

HGD, High-grade dysplasia; L TAB, left thoracoabdominal; THE, transhiatal esophagectomy.

RESULTS

There were 3 operative deaths (3.7%). Cause of death was respiratory failure in 2 patients and pulmonary artery rupture from a pulmonary artery catheter balloon in 1 patient. Postoperative complications occurred in 50 patients (62.5%), including atrial fibrillation in 19 (23.8%), anastomotic leak in 17 (21.3%), pneumonia in 16 (20%), wound infection in 16 (20%), prolonged need for mechanical ventilation in 11 (13.8%), empyema in 3 (3.8%), and chylothorax in 3 (3.8%). Ten of the patients with anastomotic leak required reoperation, whereas 7 patients were successfully managed nonoperatively. The leak rate for a cervical anastomosis was 38.5% compared with 20.7% in the left side of the chest and 15.8% in the right side of the chest. Sixteen patients (20%) required reoperation for complications. Ten patients underwent reoperation to repair anastomotic leak or to address complications of leak, such as empyema or gastrocutaneous fistula. For the remaining 6 patients requiring reoperation, the reason was chylothorax, abdominal wound dehiscence, reexploration for bleeding from the aorta, twisted gastric conduit, herniated small bowel, and gastroparesis in 1 patient each. The median time interval between esophagectomy and reoperative procedure was 21 days(range, 1 day to 2.1 years). The median length of stay was 11.5 days (range, 7–165 days).

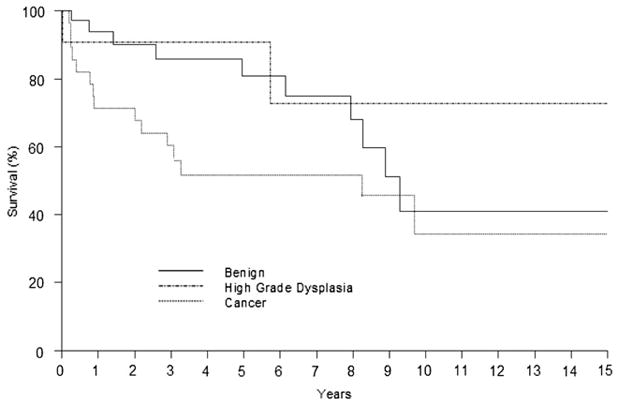

The median follow-up was 38.2 months (range, 1 month to 19.6 years) and was complete in 98.7% of patients. Anastomotic stricture developed in 19 patients (23.8%) requiring at least 1 dilation. The median number of dilations required in those with anastomotic stricture was 2 (range, 1–17). At the time of last follow-up, there were 55 patients alive, 24 patients had died, and 1 patient was lost to follow-up. Figure 1 shows long-term survival by diagnosis.

FIGURE 1.

Survival after esophagectomy in patients with prior anti-reflux surgery. Zero time represents the hospital discharge date.

There were no statistically significant clinical differences between the 80 patients who had undergone previous anti-reflux surgery and the 160 matched control patients who did not have anti-reflux surgery before esophagectomy except with respect to the surgical approach used for esophagectomy and the resulting location of the anastomosis (Table 2). In the patients with prior anti-reflux surgery, the left thoracoabdominal approach was used more frequently and the transhiatal and McKeown approaches were used less frequently than in the control group. As a result, patients who underwent esophagectomy after an anti-reflux operation had more anastomoses in the left side of the chest and fewer in the left side of the neck than in the control group. This was particularly true for the patients who underwent esophagectomy for benign disease or failed anti-reflux surgery. A left thoracoabdominal approach was used in 53.7% of these patients compared with only 17.9% of patients undergoing esophagectomy for malignancy. In contrast, the Ivor Lewis approach was used more frequently in the patients with previous anti-reflux surgery who underwent esophagectomy for malignancy (64.1% vs 31.7%). Although the median length of hospitalization was similar between cases and control groups (11.5 days vs 11.0), the mean length of hospitalization in the patients with prior anti-reflux surgery was significantly longer than the patients with no prior anti-reflux surgery (21.3 ± 24.3 days vs 14.1 ± 9.1 days; P <001). There were significant differences between the patients with prior anti-reflux surgery and the matched control group in rates of postoperative complications (62.5% vs 36.9%, P < 001), anastomotic leaks (21.5% vs 10.6%, P = .03), and need for reoperation (20% vs 8.7%, P = .03).

Univariate analysis of the cases and controls revealed that increasing age (odds ratio [OR], 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04–1.49; P = .02) and a history of anti-reflux surgery before esophagectomy (OR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.56–4.70; P <.0004) were the only factors associated with increased risk of postoperative complications. In a multivariable model, a transhiatal or McKeown surgical approach (OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.02–3.36; P = .04) and history of anti-reflux surgery (OR, 3.19; 95% CI, 1.76–5.78; P = .0001) were associated with increased risk of complications. History of anti-reflux surgery was also the only factor in univariate and multivariate analyses associated with increased risk of anastomotic leak (OR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.09–4.73; P = .02) and need for reoperation (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.01–5.19; P = .04).

In univariate analysis of the cases, an increased number of prior anti-reflux operations before esophagectomy was associated with an increased risk of anastomotic leaks (OR, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.20–6.37; P = .02) and a need for reoperation (OR, 2.67; 95%CI, 1.13–6.27; P = .02). A cervical anastomosis was associated with an increased risk of anastomotic leak (OR, 3.27; 95%CI, 0.89–12.09; P = .04). None of the factors analyzed were associated with an increased risk of developing anastomotic stricture.

Univariate analysis revealed that increasing age (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.36–1.99, P <.001), age greater than 60 years (OR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.61–4.32, P = .0001), a cancer diagnosis (OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.29–3.10; P = .002), and more advanced cancer stage (OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 11.56–2.70; P <.0001) were associated with an increased risk of death. In multivariate analysis, increasing age (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.32–1.95; P<.0001) and more advanced cancer stage (OR, 3.90; 95% CI, 2.32–6.52; P <.0001) were the only independent predictors of death.

DISCUSSION

Esophagectomy can be a complex operation and historically has been reported to have significant morbidity and mortality. In-hospital mortality rates ranging from 7% to 9.8% have been reported based on analyses of large nationwide administrative databases, such as the Department of Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.15,16 Given the accruing evidence of the beneficial effects of case volume on esophagectomy outcomes, in low-volume centers, mortality rates may be even higher.17,18 The most common complications are respiratory and cardiac.15,16,19 The incidence of pneumonia in large contemporary database series ranges from 21.4% to 29.9%, with respiratory failure requiring reintubation occurring in 16.2%.15,19 Atrial fibrillation occurs in approximately 12% to 17% of patients.9,20 The incidence of anastomotic leak varies widely. Rates from 0% to 30% have been reported.11,14,21 In contemporary reports from large database series, anastomotic leak rates from 8.3% to 11.3% have been reported.22,23

In our study, patients who underwent esophagectomy after previous anti-reflux surgery experienced higher morbidity when compared with a frequency-matched control group of comparable patients undergoing esophagectomy without prior anti-reflux surgery. These complication rates are also higher than historically reported morbidity occurring in other series. Postoperative complications occurred in 62.5% of our patients, which is significantly higher than the 36.9% rate in the matched control group of patients without prior anti-reflux surgery. Patients who underwent anti-reflux surgery before esophagectomy had a 3.19 increased risk of postoperative complications (P = .0001) compared with those with no prior surgery. This postoperative complication rate is also higher than the 37% complication rate that we observed at the Mayo Clinic from 1998 to 2003 in a series of 162 patients who underwent esophagogastrectomy after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.14 We also observed a complication rate of 37.7% in a group of 220 consecutive patients with esophageal cancer who underwent Ivor Lewis esophagogastrectomy at the Mayo Clinic between 1992 and 1995.9 The higher morbidity we observed in this study may be partly due to the pre-esophagectomy status of many of the patients. Many had experienced gastrointestinal discontinuity after failed anti-reflux surgery, with significant clinical deterioration and sepsis. Forty-four percent of the patients had complications after their anti-reflux surgery, and 24% had leaks after their anti-reflux operation. Esophagectomy in this setting can be complicated by a difficult and lengthy dissection, destroyed tissue planes, and poor tissue quality.

Occurrence of the early anastomotic complications of conduit ischemia and anastomotic leak has a significant impact on the outcomes after esophagectomy. They are associated with an increased morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy and are risk factors for the development of the late complication of anastomotic stricture.24,25 Conduit necrosis is uncommon, with an incidence of approximately 1%.26 It usually occurs secondary to a significant ischemic insult to the conduit, such as injury to the right gastroepiploic artery. This did not occur in our series, although in 3 patients an intraoperative assessment by the surgeon judged the stomach to be unsuitable for reconstruction and colon was used as an alternative conduit. In all 3 patients, no direct injury to the right gastroepiploic artery occurred; rather, the appearance of the stomach seemed unfavorable after a lengthy mobilization of the previous fundoplication wrap. The stomach was used as the conduit in 69 of the 79 patients (87%) who underwent esophageal reconstruction. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the cases showed that there was no difference in rates of postoperative complications, anastomotic leak, need for reoperation, anastomotic stricture, or long-term survival in those with a gastric conduit compared with those who had a colon or small bowel conduit used for reconstruction.

The anastomotic leak rate of 21.5%observed in this study is significantly higher than the leak rate of 10.6% observed in the frequency-matched control group. It is also significantly higher than the 11.7% anastomotic leak rate we reported in the 162 patients undergoing esophagogastrectomy for esophageal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy at the Mayo Clinic between 1998 and 2003.14 Patients with a history of anti-reflux surgery before esophagectomy had a 2.3 times increased risk of anastomotic leak (P =.02) compared with those with no prior anti-reflux surgery. Furthermore, we also found that the leak rate of an anastomosis in the neck was 38.5% compared with 21.4% for a left-sided chest anastomosis and a 15.8% leak rate for a right-sided chest anastomosis. These anastomotic leak rates for intrathoracic anastomoses are significantly higher than the leak rate we reported in the 761 patients who underwent esophagectomy with an intrathoracic anastomosis at the Mayo Clinic from 1993 to 2003.24 Patients with a neck anastomosis had a 3.3 times increased risk of anastomotic leak (P = .04). The number of previous anti-reflux surgeries before esophagectomy was also associated with a significantly increased risk of developing an anastomotic leak. These findings are consistent with what other investigators have reported. A recent study of 1133 transhiatal esophagectomies from the University of Michigan also found that an increased number of prior esophagogastric operations was associated with a 2.3 times increased risk of developing a cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leak.25 We believe that the major etiologic factor underlying these increased rates of anastomotic failure is that the increased operative trauma needed to take down scarring around the previously operated on gastric fundus may place the conduit at increased risk of ischemia.

The need for reoperation because of early complications was also significantly higher in the group of patients with prior anti-reflux compared with the frequency-matched control group (20%vs 8.7%, P = .03). This is partly a function of the higher anastomotic leak rate in the patients with prior anti-reflux surgery and the higher rate of postoperative complications in this group of patients. Ten of the patients with prior anti-reflux surgery who developed anastomotic leaks required reoperation.

The impact prior anti-reflux surgery has on the outcomes of subsequent esophagectomy was addressed by Casson and colleagues.27 Of a consecutive series of 142 patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma who underwent esophageal resection, 15 were identified who had undergone prior anti-reflux surgery. All 15 patients had undergone fundoplication using an “open” surgical approach (11 transabdominal Nissen and 4 transthoracic Belsey procedures). Gastric transposition and cervical esophagogastrostomy were technically feasible in all 15 patients with prior fundoplication. There was no difference in anastomotic leak rates, morbidity, or subsequent anastomotic stricture rates based on whether patients had undergone previous fundoplication. In comparing these results with our findings, there are several notable differences in the patient characteristics. First, in our series, the indication for esophageal resection and reconstruction in the majority of our patients was to treat complications of prior anti-reflux surgery or failed anti-reflux surgery. In contrast, all 142 patients in the study by Casson and colleagues were undergoing esophagectomy to treat esophageal adenocarcinoma. In addition, in our study 28 of the patients (35%) had undergone at least 2 prior anti-reflux procedures before the esophagectomy. None of the patients reported by Casson and colleagues had more than 1 prior anti-reflux operation. One of the important findings in our study is that an increased number of prior anti-reflux operations was associated with increased risk of anastomotic leak and need for reoperation. Finally, 13 of the patients in our study at the time of anti-reflux surgery had evidence of a shortened esophagus and in turn had esophageal lengthening by gastroplasty. None of the patients in Casson and colleagues’ study had undergone a prior gastroplasty.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is that it is a retrospective analysis of a group of patients treated surgically by 6 different surgeons over a 21-year period at a single institution. In addition, the patients were a heterogeneous group. At the time of esophagectomy, some patients had undergone multiple failed previous operations with significant clinical deterioration and sepsis. These patients would be expected to be at greater risk for postoperative complications than those patients undergoing esophagectomy in an elective setting.

CONCLUSIONS

Esophagectomy after prior anti-reflux surgery is challenging. The stomach is usually a suitable conduit for esophageal replacement in these circumstances. Patients with a history of anti-reflux surgery who undergo esophagectomy are at significantly increased risk for postoperative complications, including anastomotic leak, and need for re-operation compared with patients who have not undergone prior anti-reflux surgery. In light of the increased risk of cervical anastomotic leaks, intrathoracic anastomosis may be preferable.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the expert advice and statistical assistance of Rachel Gullerud, BS, and W. Scott Harmsen, MS, from the Department of Health Sciences Research at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CI

confidence interval

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Presented at the 35th Annual Meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association, June 24–27, 2009, Fairmont Banff Springs, Banff Springs, Alberta, Canada.

References

- 1.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, Adams E, Cronin K, Goodman C, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500–11. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jehaes C, Markiewicz S, Lombard R. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:138–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter JG, Smith CD, Branum GD, Waring JP, Trus TL, Cornwell M, et al. Laparoscopic fundoplication failures: patterns of failure and response to fundoplication revision. Ann Surg. 1999;230:595–604. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199910000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaninotto G, Portale G, Contantini M, Rizzetto C, Guirroli E, Geolin M, et al. Long-term results (6–10 years) of laparoscopic fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1138–45. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rathore MA, Andrabi SI, Bhatti MI, Najfi SM, McMurray A. Metaanalysis of recurrence after laparoscopicrepair of paraesophagealhernia. JSLS. 2007;11:456–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohnmacht GA, Deschamps C, Cassivi SD, Nichols FC, Allen MS, Schleck CD, et al. Failed antireflux surgery: results after reoperation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:2050–4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young MM, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, Allen MS, Miller DL, Schleck CD, et al. Esophageal reconstruction for benign disease: early morbidity, mortality, and functional results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1651–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01916-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young MM, Deschamps C, Allen MS, Miller DL, Trastek VF, Schleck CD, et al. Esophageal reconstruction for benign disease: self-assessment of functional outcome and quality of life. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1799–802. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01856-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visbal AL, Allen MS, Miller DL, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, Pairolero PC. IvorLewis esophagogastrectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1803–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behzadi A, Nichols FC, Cassivi SD, Deschamps C, Allen MS, Pairolero PC. Esophagogastrectomy: the influence of stapled versus hand-sewn anastomosis on outcome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1031–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vigneswaran WT, Trastek VF, Pairolero PC, Deschamps C, Daly RC, Allen MS. Extended esophagectomy in the management of carcinoma of the upper thoracic esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:901–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigneswaran WT, Trastek VF, Pairolero PC, Deschamps C, Daly RC, Allen MS. Transhiatal esophagectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:838–44. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90341-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 6. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donahue JM, Nichols FC, Li Z, Schomas DA, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, et al. Complete pathologic response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer is associated with enhanced survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:392–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey SH, Bull DA, Harpole DA, Rentz JJ, Neumayer LA, Pappas TN, et al. Outcomes after esophagectomy: a ten-year prospective cohort. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:217–22. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04368-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohn GP, Galanko JA, Meyers MO, Feins RH, Farrell TM. National trends in esophageal surgery-are outcomes as good as we believe? J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1900–12. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewars AE, Goodney PP, Wenberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swisher SG, Deford L, Merriman KW, Walsh GL, Smythe R, Vaporicyan A, et al. Effect of operative volume on morbidity, mortality and hospital use after esophagectomy for cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:1126–34. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2000.105644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connors RC, Reuben BC, Neumeyer LA, Bull DA. Comparing outcomes after transthoracic and transhiatal esophagectomy: a 5-year prospective cohort of 17,395 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:735–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaporicyan AA, Correa AM, Rice DC, Roth JA, Smythe WR, Swisher SG, et al. Risk factors associated with atrial fibrillation after noncardiac thoracic surgery: analysis of 2588 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;123:779–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathisen DJ, Grillo HC, Wilkens EW., Jr Transthoracic esophagectomy: a safe approach to carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45:137–43. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright CD, Kucharczuk JC, O’Brien SM, Grab JD, Allen MS. Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database. Predictors of major morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: A Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database risk adjustment model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:587–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Escofet X, Majunath A, Tuinec C, Havard TJ, Clark GW, Lewis WG. Prevalence and outcome of esophagogastric anastomotic leak after esophagectomy in a UK Regional Cancer Network. Dis Esophagus. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00995.x. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crestanello JA, Deschamps C, Cassivi SD, Nichols FC, Allen MS, Schleck C, et al. Selective management of intrathoracic anastomotic leak after esophagectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briel JW, Tamhankar AP, Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Johansson J, Choustoulakis E, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for ischemia, leak, and strictures of esophageal anastomosis: gastric pull-up versus colon interposition. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:536–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cassivi SD. Leaks, strictures and necrosis: a review of anastomotic complications following esophagectomy. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004:16124–32. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casson AG, Madani K, Mann S, Zhao R, Reeder B, Lim HJ. Does previous fundoplication alter the surgical approach to esophageal adenocarcinoma? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:1097–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]