Abstract

The small GTPase Rab4 is implicated in endocytosis in all cell types, but also plays a specific role in some regulated processes. To better understand the role of Rab4 in regulation of vesicular trafficking, we searched for an effector(s) that specifically recognizes its GTP-bound form. We cloned a ubiquitous 69-kDa protein, Rabip4, that behaves as a Rab4 effector in the yeast two-hybrid system and in the mammalian cell. Rabip4 contains two coiled-coil domains and a FYVE-finger domain. When expressed in CHO cells, Rabip4 is present in early endosomes, because it is colocated with endogenous Early Endosome Antigen 1, although it is absent from Rab11-positive recycling endosomes and Rab-7 positive late endosomes. The coexpression of Rabip4 with active Rab4, but not with inactive Rab4, leads to an enlargement of early endosomes. It strongly increases the degree of colocalization of markers of sorting (Rab5) and recycling (Rab11) endosomes with Rab4. Furthermore, the expression of Rabip4 leads to the intracellular retention of a recycling molecule, the glucose transporter Glut 1. We propose that Rabip4, an effector of Rab4, controls early endosomal traffic possibly by activating a backward transport step from recycling to sorting endosomes.

Rab proteins regulate discrete transport steps along the biosynthetic/secretory pathway, as well as the endocytic pathways (1, 2). The small GTPase Rab4 is associated with early endosomes (3) and recycling endosomes (4). It has been implicated in the regulation of the recycling of internalized receptors back to the plasma membranes (3, 5). Furthermore, Rab4 seems to have a more specialized role in receptor-mediated antigen processing in B lymphocytes (6), in calcium-induced α-granule secretion in platelets (7), and in α-amylase exocytosis in exocrine pancreatic cells (8). Rab4 appears also to control the subcellular distribution of the glucose transporter isoform Glut 4, specifically expressed in the insulin-sensitive adipose and muscle tissues (9–11).

However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the function of Rab4 are not fully understood. Rab proteins interact with a downstream effector(s) that specifically recognizes their GTP-bound conformation. The identification of such an effector(s) could help to better illustrate the role of Rab4 in regulation of vesicular trafficking. Thus, we searched for Rab4 effectors by screening a cDNA library in the yeast two-hybrid system by using a GTP-bound form of Rab4 (Rab4 Q67L) as bait. This screening led to the identification of Rabip4, an endosomal FYVE-finger-containing protein that, when overexpressed in CHO cells, leads to modifications of the endosomal compartment morphology and increases the intracellular amount of the ubiquitous glucose transporters, Glut 1, which recycle through the endocytic pathway. Rabip4 strongly increases the degree of colocalization of markers of sorting and recycling endosomes with active Rab4. We propose that Rabip4 controls early endosomal traffic possibly by activating a backward transport step from recycling to sorting endosomes.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against the myc epitope (9E10) and against EEA1 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY), respectively. Rabbit polyclonal anti-Rab4 has been described (9). Polyclonal anti-Rabip4 was obtained by immunizing a rabbit with the fusion protein glutathione-S-transferase-Rabip4 (). Rabbit anti-mouse Ig was from Dako. Texas red-coupled anti-mouse Ig and Cy5-coupled anti-rabbit Ig were from Amersham Pharmacia and Jackson ImmunoResearch, respectively.

cDNA Constructs.

pLexA-Rab4 wild-type (WT) or mutated forms were obtained by subcloning Rab4 cDNAs from the pCis2-constructs (9). Mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of double-stranded DNA into pCis2 plasmid (Transformer kit, CLONTECH) (9). The Rabip4 cDNA sequences were subcloned into the pACT2 vector (CLONTECH). Rabip4 was subcloned into pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). pEGFP-C1-Rabip4 (CLONTECH) was used for expression of Rabip4 as a C-terminal fusion with the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Deletion of the 11 amino acids (507) of Rabip4 was obtained by site-directed mutagenesis (QuickChange, Stratagene).

A pcDNA3-myc vector was obtained by inserting the DNA sequence of the myc epitope (AEEQKLISEEDLLK) after an initiation codon into the EcoRV site of pcDNA3.1. The cDNA for Rab4 WT, Q67L, N121I, and Rab11b was subcloned in this vector, which allows for the expression of myc-tagged proteins at their N terminus. The pCis2 Glut 1-myc was obtained as described previously for Glut 4 (9), with the myc epitope inserted between amino acids 69–70 of Glut 1. Rab11b was amplified by using a Marathon-Ready rat adipocyte cDNA library (CLONTECH) as a template. The amino acid sequence of rat Rab11b was 99% identical to that of mouse Rab11b.

Two-Hybrid Screening and Interaction Measurement.

The yeast reporter strain L40 was transformed with pLexA-Rab4 Q67L using a lithium acetate-base method and grown in synthetic medium lacking tryptophan (12). It was transformed with a T3 adipocyte library made in pVP16 plasmid. Cells were plated on synthetic medium lacking leucine, tryptophan, and histidine. Growing colonies were tested for β-galactosidase activity. Library plasmids from positive clones were rescued into Escherichia coli HB101 cells plated on leucine-free medium and analyzed by transformation tests and DNA sequencing. For interaction measurement, cotransformed L40 yeasts were selected on medium lacking leucine and tryptophan and induction of the reporter gene LacZ was quantified.

Cloning of the Full-Length Rabip4 cDNA.

The full-length cDNA was obtained by 5′ and 3′ rapid amplifications of cDNA ends (RACE) using premade mouse Skeletal Muscle Marathon-Ready cDNA (CLONTECH), according to the manufacturer protocols. To amplify the complete coding sequence of Rabip4, oligonucleotides corresponding to the sequences before the ATG initiation codon and after the 3′ stop codon were selected. The cDNA coding for Rabip4 was sequenced on the two strands by Eurogentec service.

Tissue Distribution of Rabip4.

The multiple Northern blot containing poly(A) mRNA from mouse tissues was obtained from CLONTECH. An [α-32P]dCTP-labeled fragment corresponding to the coding sequence of Rabip4 was hybridized to the membrane for 2 h at 65°C in ExpressHyb Solution (CLONTECH), washed, and autoradiographed.

Cells and Transfections.

CHO cells were grown in Ham's F-12 medium with 10% FCS and transiently transfected by electroporation. Cells (1–2 × 106/400 μl of Ham's F-12) were placed in a 0.4-cm gap cuvette along with 10–50 μg of plasmids and electroporated (260 V and 1,050 μF) with an Easyject electroporator system (Equibio, Ashford, U.K.). A CHO cell line stably expressing GFP-Rabip4 was obtained by selection with G418 (500 μg/ml) and limit dilution of cells transfected with pEGFP-Rabip4.

Electron Microscopy.

Control cells or GFP-Rabip4-overexpressing cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (1 h at 4°C) and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide. Cells were then embedded in Epon. For immunoelectron microscopy, cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde and embedded at low temperature into LR White resin (Hard LR White, London). Ultrathin sections were incubated with or without anti-Rabip4 antibodies and then with 10 nm colloidal gold-conjugated anti-rabbit Ig (BB International, Cardiff, U.K.). The sections were examined by using a JEOL 1200 EXII electron microscope.

Confocal Immunofluorescence Microscopy.

Cells grown on glass coverslips were washed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells expressing GFP-fusion proteins were directly mounted in Mowiol (Hoechst Pharmaceuticals) and examined in scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy (TCS SP, Leica, Deerfield, IL). To detect non-GFP-fusion proteins, cells were permeabilized in PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1% FBS, incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies, washed, and incubated with secondary antibodies coupled with Texas Red or Cy5 fluorochromes. The cells were examined by sequential excitation at 488 nm (GFP), 568 nm (Texas Red), and 647 nm (Cy5). The images were then combined and merged by using photoshop (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

Quantification of Glut 1 in Plasma and Total Membranes.

Cells (stably overexpressing Rabip4 or not) were transiently transfected with 20 μg pCis2 Glut 1-myc. Two days later, cells were fixed in duplicate with 4% paraformaldehyde. In one well, cells were permeabilized to determine the total amount of Glut 1-myc, whereas the other untreated well was used to quantify the plasma membrane Glut 1-myc (9). Cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with anti-myc mAb (4 μg/ml), washed, incubated with rabbit anti-mouse Ig, and then with [125I]protein A. Cells were scraped for radioactivity and protein determinations. The levels of Glut 1-myc overexpression were identical in both cell lines.

Results and Discussion

Identification of a Rab4-Interacting Protein.

L40 yeasts were transformed with a plasmid encoding a fusion protein between Rab4 Q67L, a GTPase-deficient mutant (9), and the DNA binding domain of LexA, which recognizes specific DNA sequences upstream of the two reporter genes HIS3 and LacZ. The established strain was transformed with a yeast two-hybrid mouse T3 adipocyte cDNA library fused to the VP16 transcriptional activation domain. Screening of 106 transformants yielded three clones that strongly interacted with Rab4 Q67L but not with lamin. One of these clones, named I1, was further characterized in the yeast system (Table 1 Left). It induced β-galactosidase activity only when coexpressed with LexA-Rab4 Q67L, but not with active forms of Ras, Rab5, and Rab6. We did not detect any interaction between VP16- I1 and LexA-Rab4 WT, or N121I or S22N, two mutated Rab4 proteins that do not bind GTP (9). Furthermore, two mutations in the effector domain (T40A or G42D) totally abolished the interaction with I1. Thus, the sequence encoded by the I1 clone preferentially recognizes the GTP-bound Rab4, leading us to clone the full-length cDNA.

Table 1.

Characterization of the interactions between the initial clone I1 or the protein Rabip4 and various Rab4 proteins in the yeast two-hybrid system

| LexA Fusion | β-Galactosidase activity, arbitrary units

|

|

|---|---|---|

| VP16-I1 | pACT2-Rabip4 | |

| Lamin | 70 ± 8 | 210 ± 20 |

| Rab4 Q67L | 2,340 ± 58 | 1,700 ± 180 |

| Rab4 WT | 39 ± 3 | 48 ± 2 |

| Rab4 N121I | 42 ± 3 | 446 ± 67 |

| Rab4 S22N | 7 ± 1 | 33 ± 14 |

| Rab4 Q67L Δ CT | ND | 2,860 ± 851 |

| Rab4 Q67L T40A | 42 ± 5 | 26 ± 8 |

| Rab4 Q67L G42D | 9 ± 2 | 46 ± 10 |

| Ras G12V | 4 ± 1 | 20 ± 10 |

| Rab5 Q79L | 5 ± 2 | 38 ± 20 |

| Rab6 Q72L | 4 ± 1 | 10 ± 5 |

| Rap2 G12V | ND | 30 ± 15 |

L40 yeasts were cotransformed with the pLex constructs encoding for LexA-fusion proteins, and the rescued VP16-I1 or pACT2-Rabip4. β-galactosidase activities are presented as means ± SEM obtained with 3–6 independent transformants. The expression of the LexA-Rab4 fusion proteins, checked by immunodetection, was similar in all conditions. ND, not determined.

An additional 0.7-kb fragment, which contained an in-frame stop codon and the poly(A) tail, was produced by 3′-RACE. The upstream 5′ end was obtained by 5′-RACE that gave an additional 1.2-kb sequence, with two ATG in frame with the amino acid sequence of the I1 clone. The second ATG was in a consensus Kozak sequence (13). Analysis of the total cDNA revealed an ORF that encoded for a 600-aa protein (Fig. 1A; named Rabip4 for Rab4 interacting protein) in which the original I1 clone corresponded to amino acids 401–517. The expression of the cDNA, both in the reticulocyte lysate system and after transient transfection into CHO cells, led to the appearance of a 69-kDa protein, in accordance with the predicted molecular weight (data not shown). Similar to the I1 clone, Rabip4 specifically interacted with active Rab4 in the yeast two-hybrid system (Table 1 Right). The C-terminal Cys-Gly-Cys motif required for Rab4 geranylgeranylation was not required for the interaction. Furthermore, there was no interaction with active Rap2 despite the 30% homology of the N terminus of Rabip4 (amino acids 1–140) with the Rap2 interacting protein 8, an effector of the small GTPase Rap2 (14). Rabip4 thus behaves as a Rab4 effector in the yeast system.

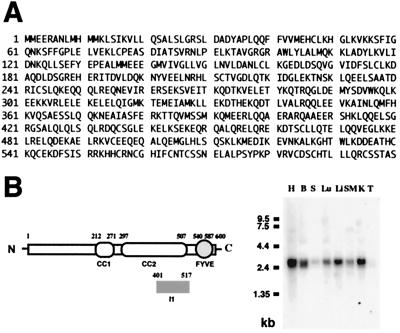

Figure 1.

Obtention and characteristics of Rabip4 sequence. (A) Deduced amino acid sequence of the ORF in the Rabip4 cDNA. (B) Predicted structural organization of Rabip4 functional domains and tissue distribution of Rabip4 mRNA. The numbers at the top indicate the amino acid residues that define the boundaries of the coiled-coil (CC) and FYVE domains. The position of the I1 clone is indicated. The mouse tissue Northern blot was hybridized with the labeled probe corresponding to the 1.8-kb Rabip4 cDNA. H, heart; B, brain; S, spleen; Lu, lung; Li, Liver; SM, skeletal muscle; K, kidney; T, testis.

Characteristics of Rabip4.

The protein sequence of Rabip4 is hydrophilic with no potential signal sequence or membrane spanning domain. Its putative structural characteristics, schematized in Fig. 1B first reveal two regions predicted to be mainly α-helical with heptad repeats characteristic of coiled-coil domains (15), domains characterized as protein–protein interaction determinants, named CC1 () and CC2 (). Thus, Rabip4, through its coiled-coil domains, might interact with itself and/or with other proteins to form a large complex as described for other Rab. For example, the Rabaptin5–Rabex complex and EEA1, two Rab5 effectors, are found together in an oligomeric complex also containing the N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor and Syntaxin 13 (16, 17). Second, Rabip4 contains in its C terminus (amino acids 540–587) one consensus sequence for a FYVE-finger, a cysteine-rich zinc-finger-like motif that coordinates two zinc atoms and has conserved basic amino acids surrounding the third cysteine. This motif was recently identified as a phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate binding motif (18–20) and is found in a number of proteins playing a role in membrane traffic, such as the mammalian proteins Hrs (21), EEA1 (22), and PIKfyve (23), which are associated with endosomes. This endosomal localization is certainly determined by the enrichment of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in endosomes (24). The highest homology (56%) was found between the FYVE fingers of Rabip4 and EEA1 (20, 25, 26). The homology between the two proteins is not restricted to the FYVE finger, but extends over the two-thirds of Rabip4 (amino acids 190–600), which are 40% identical to EEA1.

The tissue distribution of Rabip4 mRNA was determined by using a mouse multiple-tissue Northern blot hybridized with a radiolabeled probe containing the 1.8-kb coding sequence of Rabip4. A 2.5-kb transcript was found expressed in all tested tissues, with the lowest levels of expression in testis and spleen (Fig. 1B).

To determine which domain(s) is involved in the interaction between Rabip4 and Rab4 Q67L, we transformed yeast with pLexRab4Q67L and different constructs of Rabip4 fused with the transcriptional activation domain of Gal4 cloned in the pACT2 vector (Table 2). Rabip4 (), which contains the I1 sequence (), interacted with Rab4 Q67L, whereas the C-terminal end, Rabip4 (), which includes the FYVE domain, did not. Neither the Rabip4 N-terminal sequence (), nor the coiled-coil domains, CC1 and/or CC2, interacted with Rab4 Q67L. This series of observations indicated that the ten amino acids following the end of the CC2 are crucial for this interaction. Accordingly, the deletion of amino acids 507–517 (Rabip4 Δ507–517) led to the disruption of the interaction between Rabip4 and Rab4 Q67L. This sequence (LHLSQSKLKME), which appeared to be required for Rab4 binding, was not found in any other proteins, including Rabaptin-5 and Rabaptin4, known to interact with Rab4 (27, 28).

Table 2.

Determination of the interacting domain of Rabip4 with LexA-Rab4 Q67L

| Activation domain fusion (pACT2) | Interaction (β-galactosidase activity) |

|---|---|

| Rabip4 (1–600) | +++ |

| Rabip4 (401–517), I1 | ++++ |

| Rabip4 (517–600), FYVE | − |

| Rabip4 (401–600) | ++++ |

| Rabip4 (212–271), CC1 | − |

| Rabip4 (297–507), CC2 | − |

| Rabip4 (212–507), CC1–CC2 | − |

| Rabip4 (1–212) | − |

| Rabip4 Δ507–517 | − |

L40 reporter yeast cells were cotransformed with pLex-Rab4 Q67L and the indicated pACT2-Rabip4 domain constructs. A deletion of the cDNA sequence coding for amino acids 507–517 of Rabip4 was performed in Rabip4 Δ507–517. Yeast cells were grown in the absence of leucine and tryptophan and βgalactosidase activity was determined on replicate filters using X-gal as a substrate. ++++, blue coloration appeared within half an hour; +++, a coloration appearing after 1 h; and −, no coloration was obtained after 24 h. The expression of all constructs was checked by immunodetection.

Cellular Localization of Rabip4.

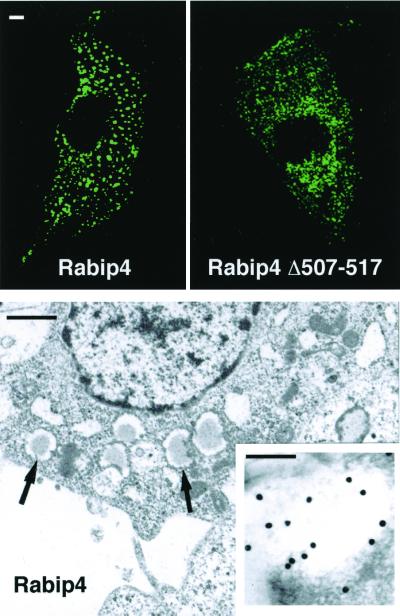

To characterize the subcellular localization of Rabip4, CHO cells overexpressing GFP-Rabip4 were analyzed by confocal and electron microscopy. GFP-Rabip4-labeled punctated structures, scattered throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 2a) with no cytosolic diffuse labeling, in accordance with the lack of Rabip4 in a cytosolic fraction analyzed by immunodetection (data not shown). It should be noted that the GFP addition did not modify the behavior of Rabip4, because identical images were obtained when WT Rabip4 was expressed (see Fig. 3). GFP-Rabip4 Δ507–517, which does not interact with Rab4 in the yeast two-hybrid system, stained punctated structures of smaller size (Fig. 2b). This observation suggests that overexpressed Rabip4, probably by interacting with endogenous Rab4, leads to the formation of enlarged vesicles, because the protein that does not interact with Rab4 labels smaller structures than does the WT Rabip4. It should be observed that the interaction of Rabip4 and Rab4 is not required for membrane association, because the GFP-Rabip4 Δ507–517 remains associated to vesicular structures. In these aspects, Rabip4 and EEA1 behave differently because overexpressed Rabip4 is nearly totally membrane-associated, whereas EEA1 partitionates between membrane and cytosol and is further recruited to early endosomes by overexpression of active Rab5 (26). Further studies will be needed to determine the domains involved in this membrane association. At the electron microscopic level, numerous 150–200 nm wide vesicles were visible, dispersed in the cytoplasm of CHO cells overexpressing GFP-Rabip4 (Fig. 2c), but not in control cells (data not shown). They were delimited by a membrane and contained a homogenous light-gray material. GFP-Rabip4 was found at the level of these vesicles by immunoelectron microscopy analysis (Fig. 2c Inset).

Figure 2.

Confocal immunofluorescence and electron microscopy of CHO cells expressing GFP-Rabip4. CHO cells were transiently transfected with pEGFP Rabip4 or pEGFP Rabip4 Δ507–517 or stably transfected with pEGFP Rabip4 for the electron microscopy studies. Cells were treated for confocal analysis (Upper) or electron microscopy (Lower). GFP-fusion proteins were observed by using FITC parameters and the figures show 0.15–0.25 μm sections of CHO cells made by confocal analysis. Bars correspond to 1 μm (Upper), 250 nm (Lower), and 100 nm (Inset). Arrows point to vesicles 150–200 nm wide. The Inset shows an immunolocalization using anti-Rabip4 serum and 10 nm colloidal gold-conjugated secondary antibody. Numerous gold beads labeled the vesicular structures, whereas no significant labeling was obtained on control cells or when anti-Rabip4 serum was omitted.

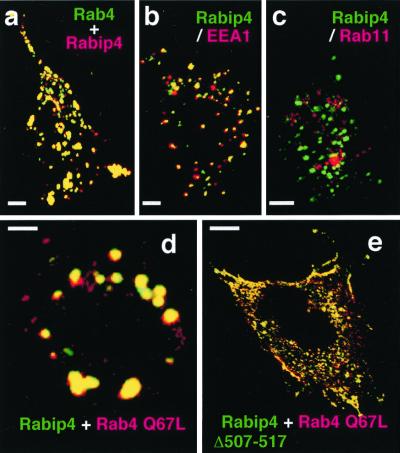

Figure 3.

Rabip4 is localized in early sorting endosomes and gives enlarged vesicles with active Rab4. CHO cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3-Rabip4 and pEGFP-Rab4 (a), pEGFP-Rabip4 (b and c), pEGFP-Rabip4 and pcDNA3 myc-Rab4 Q67L (d), or pEGFP-Rabip4 Δ(507–517) and pcDNA3 myc-Rab4 Q67L (e). Rabip4 is detected by using anti-Rabip4 antiserum and Texas Red-coupled anti-rabbit Ig (a) and myc-Rab4 Q67L is detected with mAb anti-myc followed by Texas Red-coupled anti-mouse Ig (d and e). Cells overexpressing GFP-Rabip4 were incubated with mAb anti-EEA1 (b) or with anti-Rab11 purified polyclonal Ig (c), followed by Texas Red-coupled anti-species Ig. Rab11 labeling was visible only in sections corresponding to the top of the cells (c), whereas no labeling was obtained when nonimmune Ig was used. The figures show merged images of green (GFP-labeled proteins) and red labeling obtained for the same section of representative CHO cells, with yellow color resulting from the overlay of green and red. (Bars = 1 μm.)

To determine more precisely the cellular distribution of Rabip4, we studied its localization along the endocytic pathway, in comparison with various Rab proteins (Fig. 3). We compared the distribution of overexpressed Rabip4 and GFP-Rab4 WT, because antibodies able to recognize endogenous Rab4 in immunofluorescence studies are not available. Rabip4 nearly totally colocalized with GFP-Rab4 WT in large vesicle structures (Fig. 3a). Rabip4 was also colocated with most of EEA1 (a marker of sorting endosomes) (Fig. 3b), but did not colocalize with Rab11 (a marker of recycling endosomes) present in a pericentriolar region at the top of CHO cells (Fig. 3c). It should be noted that Rabip4 expression led to an increase in the size of the EEA1-positive endosomes, compared with control cells (data not shown and ref. 29), as a likely consequence of interaction of Rabip4 with endogenous Rab4. The coexpression of Rabip4 with active Rab4 led to even more enlarged vesicles (Fig. 3d), whereas the coexpression of Rabip4 Δ507–517 with active Rab4 gave no enlargement of endosomes, despite the colocalization of both proteins (Fig. 3e). Although we were unable to evidence a coimmunoprecipitation of Rab4 and Rabip4 in cell lysates, our observations indicate that the two proteins cooperate in the cell to produce enlarged endosomes. Furthermore, the enlargement of the structures did not occur when the inactive Rab4 N121I (Fig. 5d) or a cytosolic Rab4 deleted of the Cys-Gly-Cys C-terminal motif (data not shown) was used. Because Rabip4 was also absent from the Rab7-positive, late endosomes (see Fig. 4), Rabip4 appears as a protein of sorting endosomes that, when overexpressed, leads to an expansion of this compartment that depends on the presence of active Rab4 and on its ability to interact with it.

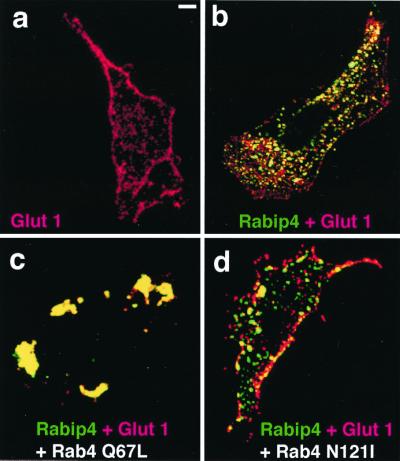

Figure 5.

Glut 1-myc distribution in cells expressing GFP-Rabip4. WT (a) or stably expressing GFP-Rabip4 (b–d) CHO cells were transiently transfected with pCis2 Glut 1-myc alone (a and b) or together with pCis2 Rab4 Q67L (c) or pCis2 Rab4 N121I (d). Three days after transfection, cells were fixed and permeabilized. Glut 1-myc is detected with anti-myc mAb and Texas red-coupled anti-mouse Ig. The merged images corresponding to green Rabip4 and red Glut 1-myc of the same confocal section are shown. Cells overexpressing Rab4 were identified by using anti-Rab4 serum and Cy5-coupled anti-rabbit Ig (data not shown). (Bar = 1 μm.)

Figure 4.

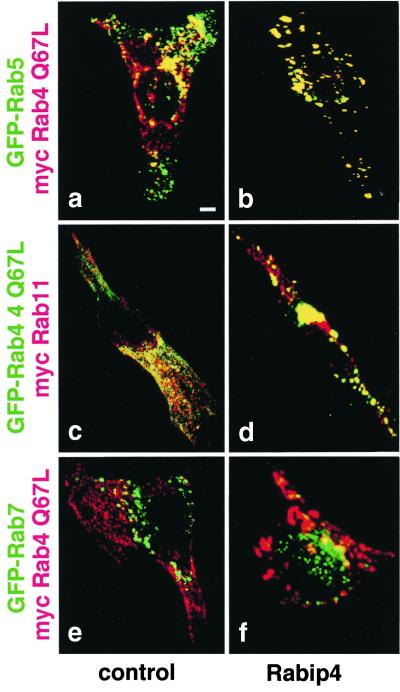

Rabip4 increases the overlap between sorting and recycling endosomes. Control CHO cells (Left) or cells transfected with pcDNA3 Rabip4 (Right) were cotransfected with pEGFP Rab5 and myc-Rab4 Q67L, with pEGFP Rab4 Q67L and myc-Rab11 or pEGFP Rab7 and myc Rab4 Q67L. Myc-tagged proteins and Rabip4 were detected as in Fig. 3. Figures represent the merged images of green and red labeling corresponding to active Rab4 compared with Rab5, Rab11, and Rab7. (Bar = 1 μm.)

Rabip4 Expression Results in the Overlap of Sorting and Recycling Endosomes.

We next wanted to determine the identity of the compartments that gave rise to enlarged structures in the presence of Rabip4 and active Rab4. Recent studies indicate that Rab4 is present on both Rab5-positive sorting endosomes and Rab11-positive recycling endosomes (4, 30, 31). We thus compared the localization of active Rab4 (Rab4 Q67L) with Rab5 or Rab11 in the absence (Fig. 4 Left) or presence of Rabip4 (Fig. 4 Right). GFP-fluorescent Rab proteins (green) and myc-tagged proteins (red) were expressed. As expected, GFP-Rab5 and myc-Rab4 Q67L (Fig. 4a) were partly colocated, similar to GFP-Rab4 Q67L and myc-Rab11b (Fig. 4c), as indicated by the presence of yellow in the merged images. By contrast, no colocalization was observed between active Rab4 and GFP-Rab7 (Fig. 4e). Rabip4 not only induced an enlargement of the structures labeled with active Rab4 (Fig. 4 b, d, and f), but also increased the overlap of Rab5 and Rab4 Q67L (Fig. 4b) and of Rab4 and Rab11b (Fig. 4d) in the enlarged vesicles. Expression of Rabip4 and Rab4 did not alter the Rab7-positive, late endosomes (Fig. 4f). Thus, the results indicate that Rabip4 and Rab4 cooperate, leading to the fusion of sorting and recycling endosomes and the appearance of enlarged early endosomal structures.

Effect of Rabip4 Expression on the Localization of Glucose Transporters Glut 1.

We then wanted to examine the functional consequence of Rabip4 expression on the fate of the ubiquitous glucose transporter Glut 1, taken as a model of recycling molecules (32). In CHO cells, Glut 1-myc is present intracellularly into punctate structures and at the margins of the cell that correspond to the plasma membranes (Fig. 5a). Quantification of the Glut 1-myc molecules, performed as described in Materials and Methods, indicated that 51 ± 4% of the transporters were present at the cell surface in control cells. By contrast, in CHO/GFP-Rabip4 cells, stably expressing GFP-Rabip4, Glut 1-myc was essentially intracellular with few labeling at the plasma membrane (Fig. 5b). Indeed, only 23 ± 5% (± SEM of four experiments) of the Glut 1-myc molecules were present at the cell surface. This effect of Rabip4 certainly required endogenous Rab4 to be under its active form. Indeed, when the inactive Rab4 N121I, which could act as a dominant negative molecule, was expressed with Rabip4, Glut 1-myc was present at the margins of the cells (Fig. 5d). This suggests that Rab4 N121I blocked the redistribution of Glut 1-myc induced by GFP-Rabip4. Furthermore, in CHO/GFP-Rabip4 cells expressing Rab4 Q67L, Glut 1-myc was found nearly totally together with GFP-Rabip4 in the enlarged endosomes (Fig. 5c), which were also positive for Rab4 Q67L (data not shown).

Our results indicate that expression of Rabip4 could modify the kinetic parameters of Glut 1 recycling. Although more precise kinetic information would be required, we could propose that Rabip4/Rab4 is of use to an inhibitory function in endocytosis, as already described for Rab15 (33, 34), a neuronal Rab protein (35). This inhibitory effect could result from a negative regulation of one step of recycling or from the stimulation of a pathway operating in the opposite direction (i.e., a “backward” transport between recycling and sorting endosomes). These transports would be necessary to ensure organelle homeostasis by sorting resident molecules of a donor compartment back to their initial locations. Such a backward traffic between Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum is controlled by Rab6 (36, 37). Furthermore, transferrin present in recycling endosomes can return to sorting endosomes suggesting that a backward transport step of the transferrin receptors occurs (38). According to the model of Bourne (39), effectors of a Rab protein involved in a traffic step are present on the surface of the acceptor compartment, whereas the Rab protein can be found on both donor and acceptor membranes. Several recent observations substantiate this model. Members of the exocyst complex, effector of Sec4 (proteins that control a late step of exocytosis in yeast), are present at the plasma membrane (40). EEA1, a Rab5 effector, is recruited selectively onto the acceptor early endosomes, whereas Rab5 is symmetrically distributed between the clathrin-coated vesicles and early endosomes (41). Along the same line, we would like to propose that Rabip4, which is mostly present in the sorting endosomes while Rab4 is present both on sorting and recycling endosomes, would provide directionality to a backward traffic from the recycling endosomes to the sorting endosomes. It is also possible that Rabip4 could participate in specific processes in cells in which intracellular traffic appears more specialized and where Rab4 has a specific function, such as in B lymphocytes (6), adipocytes (9, 11), or pancreatic acini (8).

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Tavitian and A. Zahraoui (Institut Curie, Paris) for the gift of Rab4 cDNA; B. Goud (Institut Curie, Paris) for anti-Rab11 antibodies, pLex-Rab5 Q79L, pLexRab6 Q72L, and Ras G12V; S. M. Hollenberg (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle) for the T3 adipocyte library cDNA; J. de Gunzburg (Institut Curie, Paris) for Rap2 G12V; and S. Méresse (Centre d'Immunologie de Marseille-Luminy, Marseille, France) for Rab5 and Rab7 cDNA. N. Gautier, S. Mari, M. Mari, and A. Doye are acknowledged for technical assistance. We thank P. Boquet, R. Ballotti, and J. F. Tanti for their stimulating discussions during the course of this study and the writing of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Special Grant APEX 97–01), by the Juvenile Diabetes Federation International (JDFI Grant 198302), by the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC Grants 4030 and 7449), by Fondation Pour la Recherche Médicale (Paris, France), and by the Région Provence Alpes Côte d'Azur and the Conseil Général des Alpes Maritimes.

Abbreviations

- EEA1

early endosome antigen 1

- CC

coiled-coil

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- RACE

rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the EMBL database (accession no. AJ250024).

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.031586998.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.031586998

References

- 1.Chavrier P, Goud B. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:466–475. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morhmann K, van der Sluijs P. Mol Membr Biol. 1999;16:81–87. doi: 10.1080/096876899294797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Sluijs P, Hull M, Webster P, Mâle P, Goud B, Mellman I. Cell. 1992;70:729–740. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trischler M, Soorvogel W, Ullrich O. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:4773–4783. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.24.4773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seachrist J L, Anborgh P H, Ferguson S G S. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27221–27228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003657200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazzarino D A, Blier P, Mellman I. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1769–1774. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.10.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shirakawa R, Yioshioka A, Horiuchi H, Nishioka H, Tabuchi A, Kita T. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33844–33849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohnishi H, Mine T, Shibata H, Ueda N, Tsuchida T, Fujita T. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:943–952. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cormont M, Bortoluzzi M-N, Gautier N, Mari M, Van Obberghen E, Le Marchand-Brustel Y. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6879–6886. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dransfeld O, Uphues I, Sasson S, Schurmann A, Joost H G, Eckel J. Exp Clin Endocrinol. 2000;108:26–36. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibata H, Omata W, Suzuki Y, Tanaka S, Kojima I. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9704–9709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fields S, Song O-K. Nature (London) 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozak M. EMBO J. 1997;16:2482–2492. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janoueix-Lerosey I, Pasheva E, de Tand M, Tavitian A, de Gunzburg J. Eur J Biochem. 1998;252:290–298. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lupas A. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:375–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christoforidis S, McBride H M, Burgoyne R D, Zerial M. Nature (London) 1999;397:621–625. doi: 10.1038/17618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBride H M, Rybin V, Murphy C, Giner A, Teasdale R, Zerial M. Cell. 1999;98:377–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kutateladze T G, Ogdurn K D, Watson W T, de Beer T, Emr S D, Burd C G, Overduin M. Mol Cell. 1999;3:805–811. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)80013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misra S, Hurley J. Cell. 1999;97:657–666. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stenmark H, Aasland R. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:4175–4183. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.23.4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komada M, Masaki R, Yamamoto A, Kitamura N. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20538–20544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mu F T, Callaghan J M, Steele-Mortimer O, Stenmark H, Parton R G, Campbell P L, McCluskey J, Yeo J P, Tock E P, Toh B H. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13503–13511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov O C, Shisheva A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24589–24597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gillooly D J, Morrow I C, Lindsay M, Gould R, Bryant N J, Gaullier J-M, Parton R G, Stenmark H. EMBO J. 2000;19:4577–4588. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mills I, Jones A, Clague M. Curr Biol. 1998;8:881–884. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00351-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simonsen A, Lippe R, Christoforidis S, Gaullier J-M, Brech A, Callaghan J, Toh B H, Murphy C, Zerial M, Stenmark H. Nature (London) 1998;394:494–498. doi: 10.1038/28879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vitale G, Rybin V, Christoforidis S, Thornqvist P, McCaffrey M, Stenmark H, Zerial M. EMBO J. 1998;17:1941–1951. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagelkerken B, van Anken E, van Raak M, Gerez L, Mohrmann K, van Uden N, Holthuizen J, Pelkmans L, van der Sluijs P. Biochem J. 2000;346:593–601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawe D C, Patki V, Heller-Harrison R, Lambright D, Corvera S. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3699–3705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheff D, Daro E, Hull M, Mellman I. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:123–129. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonnichsen B, De Renzis S, Nielsen E, Riedorf J, Zerial M. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:901–914. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rea S, James D E. Diabetes. 1997;46:1667–1677. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuk P A, Elferink L A. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26754–26764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zuk P A, Elferink L A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22303–22312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elferink L A, Anzai K, Scheller R H. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:5768–5775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez O, Antony C, Pehau-Arnaudet G, Berger E G, Salamero J, Goud B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1828–1833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White J, Johannes L, Mallard F, Girod A, Grill S, Reinsch S, Keller P, Tzschaschel B, Echard A, Goud B, et al. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:743–760. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.4.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghosh R N, Maxfield F R. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:549–561. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bourne H R, Sanders D A, McCormick F. Nature (London) 1990;348:125–132. doi: 10.1038/348125a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo W, Roth D, Walch-Solimena C, Novick P. EMBO J. 1999;18:1071–1080. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubino M, Miaczynska M, Lippé R, Zerial M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3745–3748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]