Summary

Background

Psychosocial treatment is an integral component in today's comprehensive breast cancer care. The main goal of this study was to test the feasibility (benefits and acceptance) of supportive-expressive group psychotherapy (SEGT), a short-term breast cancer-specific group therapy developed and tested in Anglo-American countries, within breast centers in Germany.

Patients and Methods

The study was realized as a single-group pre-post design. Data were analyzed by combining quantitative and qualitative research methods. The sample consisted of 49 women with breast cancer stage 1 or 2 according to TNM classification (tumor, node, metastasis).

Results

The results indicate positive acceptance of the group intervention. Quality of life, tumor-related fatigue and coping strategies improved after SEGT. 1 year after the intervention, the patients report lasting positive results from the group intervention.

Conclusions

This pilot study illustrates the importance of psychooncological group interventions for breast cancer patients and indicates that this form of outpatient psychooncological care is feasible within the German health care system, and breast centers in particular. Effectiveness has to be investigated in randomized controlled trials.

Key Words: Primary breast cancer, Psychooncology, Supportive-expressive group therapy

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Psychosoziale Behandlungsangebote sind heute integraler Bestandteil der Brustkrebsbehandlung. Die vorliegende Studie hatte zum Ziel, die Durchführbarkeit (Nutzen und Akzeptanz) einer supportiv-expressiven Gruppenpsychotherapie (SEGT), einer in anglo-amerikanischen Ländern entwickelten und getesteten psychoonkologischen Kurzzeitintervention für Brustkrebspatientinnen, in der Routineversorgung von Brustzentren in Deutschland zu überprüfen.

Patientinnen und Methoden

Die Studie wurde als Eingruppen-Prä-Post-Design durchgeführt. Für die Datenerhebung und -analyse wurden quantivative und qualitative Forschungsmethoden kombiniert. Die Stichprobe bestand aus 49 Frauen mit primärem Brustkrebs (Tumorstadien T1 und T2, nach TNM-Klassifikation (Tumor, Lymphknoten, Metastasen)).

Ergebnisse

Die Ergebnisse deuten auf eine gute Akzeptanz der Gruppenintervention hin. Nach der SEGT zeigten sich Verbesserungen im Bereich der Lebensqualität, der tumorbedingten Fatigue und der Krankheitsverarbeitung. Ein Jahr nach Abschluss der Gruppenintervention berichten die Patientinnen anhaltend positive Ergebnisse.

Schlussfolgerungen

Die Studie unterstreicht die Bedeutung psychoonkologischer Gruppentherapien für Brustkrebspatientinnen und zeigt, dass diese Form der ambulanten psychoonkologischen Behandlung in Brustkrebszentren in Deutschland durchführbar ist. Im Rahmen zukünftiger Forschung sollten präzise Wirksamkeiten und langfristige Effekte durch randomisierte, kontrollierte Studien untersucht werden.

Introduction

Psychosocial dimensions of coping with breast cancer have become a central aspect of oncological care. Women undergoing diagnosis and treatment of primary breast cancer are confronted with a variety of stressors. Studies have shown that 30–50% of women are highly distressed after surgery and during adjuvant treatment [1, 2]. The year after diagnosis is most critical for developing psychological distress. Mental health problems during adjuvant cancer treatment have been found to be associated with poorer quality of life up to 3 years after diagnosis [3, 4]. Randomized clinical trials have shown that psychosocial interventions for breast cancer patients enhance coping, social support and quality of life and reduce psychological distress [5]. Besides individual psychooncological care, group psychotherapy has been described as helpful [6, 7].

Psychosocial treatment is an integral component in today's comprehensive breast cancer care. In Germany, psychosocial treatment currently gains further support by the implementation of criteria of the German Cancer Society for certified breast centers (zertifizierte Brustzentren) [8], the newly revised guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and aftercare for breast cancer [9], and the guidelines of the Disease Management Program for breast cancer implemented by the health insurance funds. These regulations ascertain basic psychosocial care. However, specific interventions, targeting psychological distress and mood disturbances, are missing.

In order to improve psychological care in breast centers, this pilot study aims to test the feasibility of short-term breast cancer-specific group therapy within the German health care system. The feasibility includes the evaluation of benefits of the short-term group therapy for the patients and its acceptance by the patients. In addition, the patients’ experiences with this therapy were evaluated by adding qualitative research methods to quantitative methods. Supportive-expressive group therapy (SEGT) is one of the main group therapy models in oncology [10]. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the implementation of SEGT in Germany.

Methods

Sample

Patients were recruited in 2 breast centers in Freiburg, Germany, between 2005 and 2008 in 4 recruitment phases. As part of the psychosocial treatment in the centers, patients were offered psychooncological consultations. During the recruitment phases preceding the initiation of groups for SEGT, patients were informed about the therapy. In a preliminary individual session with one of the therapists, potential participants were assessed for eligibility. Moreover, all patients were informed about the study, were assured of confidentiality and were asked for informed consent. Participants had to fulfill the following eligibility criteria: (a) ≥ 18 years of age, (b) capability to understand and speak the German language, (c) diagnosed with primary breast cancer, and (d) sufficient physical stability. Criteria for exclusion were (a) severe mental disorders, with the exception of affective and anxiety disorders, (b) acute suicidal tendency or suicide attempts in the past year, and (c) severe cognitive impairment. 75% of the women attending the psychooncological consultations and fulfilling the inclusion criteria accepted to participate in the group therapy.

Intervention

SEGT is a manual-based outpatient psychotherapy approach that was specifically developed for the needs of cancer patients. Originally, it was implemented for patients with metastasized breast cancer [11, 12]. This longer-term treatment has been adapted to a brief treatment of 12 weekly sessions (1.5 h) for patients with primary breast cancer [13, 14]. The process-oriented therapeutic approach focuses on developing the capability to express emotions, the fortification of personal resources and social support, and the reduction of social isolation due to illness. Consistent with the model's existential orientation, the prospect of mortality is addressed by working through the fears of death and dying as well as the mourning of the loss of roles. The individual gains the opportunity to review life priorities and enhance her sense of control over her internal and interpersonal life dealing with the illness [10, 15]. In total, 7 SEGTs were realized in this pilot study, including n = 49 primary breast cancer patients. Each group was led by 2 trained therapists, at least one of them being a licensed psychotherapist and specialized in psychooncology. The first author (K.R.) was trained in SEGT by Prof. Spiegel and his group at Stanford University, from where the approach originated. K.R. trained and supervised all co-therapists of this study on the basis of the treatment manuals [13, 15]. Group sessions were video taped in order to monitor treatment adherence. In addition to the 12 weekly sessions, a follow-up session after 2 months was conducted by the psychooncologist.

Measures and Statistics

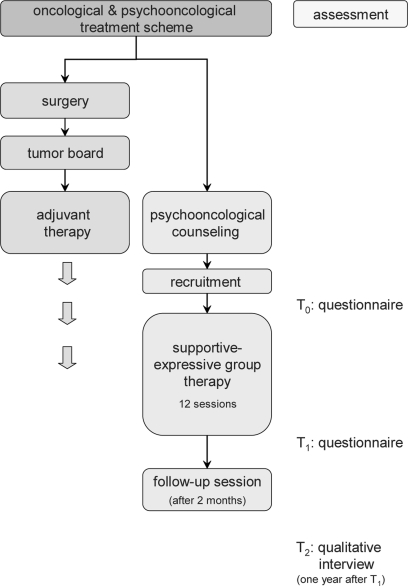

The study has a single-group pre-post design and was implemented into the routine daily care of the breast centers. Most women participated in the group therapy during the time of adjuvant treatment. The patients had to complete 2 questionnaires including the outcome measures, one before (To) and one after the intervention (T1) (fig. 1). Pre-post effect sizes were calculated.

Fig. 1.

Treatment scheme.

Both self-report questionnaires included several instruments:

-

–

Psychological distress: hospital anxiety and depression scale – German version (HADS-D) [16]

-

–

Quality of life: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality-of-life questionnaire – core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [17] and breast cancer module (EORTC QLQ-BR23) [18]

-

–

Coping with the illness: Trierer Skalen zur Krankheitsbewältigung (TSK) [19]

-

–

Patient satisfaction: Fragebogen zur Messung der allgemeinen Patientenzufriedenheit (ZUF-8) [20]

-

–

Patients’ experiences with therapy: group experience questionnaire (GEQ) [21] and qualitative interviews

For the qualitative follow-up examination, 6 patients out of 49 who had completed an SEGT in the past year and agreed to be interviewed were recruited (T2). The interviews were analyzed and rated using grounded theory, a common method in qualitative research [22].

Results

Patients

The study sample consisted of 49 women with a mean age of 46.8 years (table 1). Almost 80% had a low or medium educational level. Most patients were diagnosed with breast cancer stage 1 or 2. Most women joined the group therapy shortly after diagnosis. 49% of the women had a breast-conserving therapy and the other half underwent a mastectomy. Two-thirds received chemotherapy (table 1). As 10 patients dropped out of the study and 1 patient's data was incomplete, 38 patients were included in the pre-post analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic and medical characteristics of patients

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic data, n = 49 | |

| Age, years | |

| Mean | 46.8 |

| Range (SD) | 31–66 (8.2) |

| Citizenship, n (%) | |

| German | 46 (93.9) |

| Other | 3 (6.1) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 7 (14.3) |

| Married | 33 (67.3) |

| Separated/divorced | 8 (16.3) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |

| Low | 16 (33.3) |

| Medium | 22 (45.8) |

| High | 9 (18.8) |

| Medical data | |

| Time since diagnosis, months | |

| Mean | 8.6a |

| Range (SD) | 1–48 (10.0) |

| T, n (%) | |

| 1 | 31 (67.4) |

| 2 | 13 (26.5) |

| 3 | 5 (10.2) |

| 4 | 3 (6.1) |

| N, n (%) | |

| 0 | 27 (57.1) |

| 1 | 13 (26.5) |

| 2 | 5 (10.2) |

| 3 | 3 (6.1) |

| M, n (%) | |

| 0 | 44 (97.9) |

| 1 | 1 (2.1)b |

| Treatment, n (%) | |

| Surgery | 49 (100.0) |

| Mastectomy/lumpectomy | 25:24 (51:49) |

| Chemotherapy | 33 (67.3) |

| Radiotherapy | 28 (57.1) |

| Antihormonal treatment | 22 (44.9) |

| Antibody therapy | 2 (4.1) |

1 patient joined the group after distressing surgery for breast reconstruction 4 years after diagnosis.

l patient entered group therapy for primary breast cancer without knowledge that the tumor had already metastasized.

Benefits

Positive changes from pre to post intervention occurred especially with regard to quality of life (table 2). The strongest effects were found for global quality of life (effect size (es) = 0.55) and for future perspectives (es = 0.43). Small effect sizes based on statistically significant pre-post differences were found for emotional functioning and for the symptom-scale fatigue, as well as for search for affiliation within the coping strategies (table 2). Furthermore, small effect sizes were seen for reduction of sleep disturbances and the intensity of pain, although pre-post differences were not significant. Regarding psychological distress (assessed with HADS), no relevant overall effect sizes were found and the proportion of patients scoring above the cut-off score for psychological distress from pre- to post-intervention remained the same.

Table 2.

Changes in quality of life, distress and coping

| Pre, n = 38 | Post, n = 38 | Effect size | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of lifea, mean (SD) | ||||

| Global quality of life | 54.8 (18.1) | 64.5 (16.9) | 0.55 | 0.002∗ |

| Physical functioning | 78.4 (16.7) | 80.5 (16.4) | 0.13 | 0.331 |

| Role functioning | 56.1 (29.1) | 61.0 (27.2) | 0.17 | 0.284 |

| Emotional functioning | 48.2 (22.2) | 56.0 (22.1) | 0.35 | 0.047∗ |

| Cognitive functioning | 62.7 (27.2) | 68.0 (28.3) | 0.19 | 0.103 |

| Social functioning | 54.8 (29.0) | 60.5 (24.9) | 0.21 | 0.124 |

| Fatigue | 53.9 (24.1) | 47.0 (22.4) | 0.27 | 0.046∗ |

| Sleep disturbance | 38.2 (40.4) | 50.0 (33.0) | 0.35 | 0.077 |

| Body image | 53.5 (31.7) | 59.0 (28.2) | 0.18 | 0.232 |

| Sexual functioning | 28.4 (22.5) | 30.1 (26.3) | 0.06 | 0.634 |

| Sexual enjoyment | 61.9 (34.2) | 65.0 (17.0) | 0.11 | 0.521 |

| Future perspective | 28.9 (27.0) | 41.4 (30.8) | 0.43 | 0.021∗ |

| Systematic therapy side effects | 35.0 (20.2) | 31.2 (20.5) | 0.19 | 0.174 |

| Breast symptoms | 35.2 (21.4) | 31.5 (23.1) | 0.17 | 0.320 |

| Arm symptoms | 36.4 (24.7) | 35.7 (27.9) | 0.03 | 0.661 |

| Upset by hair loss | 50.0 (36.7) | 49.0 (41.0) | 0.03 | 0.337 |

| Intensity of pain (range 0–10)b | 4.2 (2.1) | 3.7 (2.4) | 0.22 | 0.149 |

| Distressc, mean (SD) | ||||

| Depression | 6.2 (3.7) | 5.6 (3.4) | 0.17 | 0.075 |

| Cut-off ≥ 7d | 31.6% (n = 12) | 28.9% (n = 11) | 0.03 | 0.847 |

| Anxiety | 8.3 (3.8) | 8.2 (4.0) | ||

| Cut-off ≥ 7d | 52.6% (n = 20) | 55.3% (n = 21) | ||

| Copinge, mean (SD) | ||||

| Threat minimization | 37.9 (4.3) | 37.0 (4.5) | 0.2 | 0.225 |

| Rumination | 30.2 (7.9) | 29.7 (6.7) | 0.06 | 0.787 |

| Information seeking | 31.1 (5.9) | 31.8 (5.8) | 0.12 | 0.385 |

| Search for meaning in religion | 9.9 (4.2) | 9.8 (3.6) | 0.02 | 0.867 |

| Search for affiliation | 34.7 (6.8) | 36.5 (4.5) | 0.31 | 0.009∗ |

EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BR23.

Mean values between 0 and 10; 0 = no pain, 10 = unbearable pain.

cHADS-D.

Validated cut-off scores for depression and anxiety subscale [16].

eTSK.

p < 0.05.

Acceptance

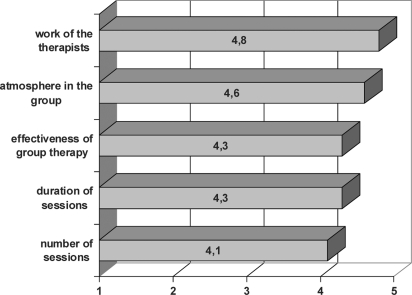

All 10 patients (20.4%) dropping out of the intervention stopped attending the group within the first 5 sessions. 5 patients dropped out because of interference between the group sessions and their medical treatment or lack of motivation. For the other 5 patients, distress was caused by group participation. Among the participating patients, each patient was on average absent during 2.1 sessions (range: 1–5 sessions). Reasons were mostly due to medical treatment or in-patient rehabilitation programs. The patients were highly satisfied with the therapeutic treatment they received (overall scale of the ZUF-8 with a mean of 28.5 (standard deviation (SD) 3.2)), which is clearly above the validated cut-off point of 24 [23]. Furthermore, different aspects of the group therapy (e.g. the work of the therapists, the atmosphere in the group) were very satisfying for the patients (fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Satisfaction with supportive-expressive group therapy (ranging from 1 = very bad to 5 = excellent).

Patients’ experiences with therapy

The most important experiences (assessed with the GEQ and qualitative follow-up interviews) were receiving support and encouragement and gaining information and understanding. Participation in the SEGT led to positive changes in relationships with others, changes in life priorities and intrapersonal changes. Patients also emphasized the importance of the opportunity to express their feelings and discuss their fears about death with others during the group therapy. As a result of the discussions, the patients realized that they were not alone with their fears. Furthermore, patients expressed in the interviews that even after 1 year the group still plays a role in their everyday life. Ongoing stabilizing relationships between group members were often reported. The process that was launched during the group therapy is continuing, and the patients have integrated the psychotherapy experience into their current lives.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to test the feasibility (benefits and acceptance) of the SEGT, a short-term breast cancer-specific therapy, within breast centers in Germany. The study was realized as a single-group pre-post design. The group therapies were integrated into the regular somatic treatment procedures within the breast centers. The study combined quantitative and qualitative research methods, being described as an enrichment for a deeper understanding of clinical effects of interventions [24].

The results show a positive acceptance of the group intervention and high satisfaction levels by our patients. 75% of the women who where offered group therapy chose to participate. The attendance rate of group sessions and the drop-out rate were comparable to randomized group intervention studies with cancer patients conducted in Anglo-American countries [5, 25]. Although studies on patient satisfaction have shown that the rates of treatment satisfaction often have a ceiling effect, which reduces their validity, the satisfaction scores reported by all patients treated in this study are remarkably high. This underlines the great value of professionally led group therapy for breast cancer patients during or right after adjuvant treatment. Furthermore, the results show improvements in the quality of life, a reduction of fatigue, and some improvements in coping strategies from pre- to post-intervention. These results are comparable with the small to medium effect sizes found in other large-scale intervention studies [26], suggesting that SEGT is beneficial for patients with primary breast cancer in Germany. However, no overall changes could be found for psychological distress (HADS scores). This floor effect is possibly due to the inclusion of patients with no or minor psychological distress prior to the intervention. The results of our qualitative follow-up evaluation point out that participation in SEGT provides the opportunity for patients to work through their individual and social issues with having breast cancer. Although SEGT is not a psychoed-ucational program, the patients report benefits from information and understanding about the cancer disease. Moreover, the interviews revealed that the group therapy had long-term positive effects. 1 year after the intervention, patients still consider the group to be important in their daily life, especially because of continuing supportive relationships with other group members. This finding, among others, illustrates the importance of psychooncological group interventions for breast cancer patients.

The pilot study has some limitations. First, there is a self-selection of the patients in the recruitment. Second, the design lacks a control group, which makes a comparison to untreated patients impossible. Therefore, the treatment results have to be interpreted with caution, leaving it open whether improvements are due to treatment or to a natural time effect. A randomized controlled trial with a larger sample would be the next step to test the effectiveness of SEGT within the German health care system. To that end, future studies should focus on women with higher initial levels of distress. Further research should also include longer follow-up assessments to explore whether the encouraging qualitative results on long-term effects of SEGT can be confirmed with quantitative methods.

Conclusion

Short-term group therapies according to the SEGT model can be conducted within the framework and the treatment routine of certified breast centers. Patients treated for primary breast cancer report benefits from this intervention regarding their quality of life and coping with the illness. Helpful experiences from the therapeutic process and the support from other patients were long lasting. The results of this pilot study indicate that this form of psychooncological care is feasible within the German health care system and that manual-based short-term group interventions are a potent way for breast centers to fulfill their goal as providers of psychooncological care.

Declaration

The trial protocol has been approved by the ethical committee of the University of Freiburg and meets the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki in its revised version of 1975 and its amendments of 1983, 1989, and 1996 [27].

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare to have no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research funding from the Felix-Burda Stiftung, München. The following breast centers collaborated in the study: Brustzentrum Südbaden and Brustzentrum der Universitäts-Frauenklinik, Freiburg. We thank Markus Birmele, Barbara Vogel, Gisela Mehren and Stefanie Weingärtner for their dedicated participation as therapists and co-therapists in the study.

References

- 1.Schwarz R, Krauss O, Höckel M, et al. The course of anxiety and depression in patients with breast cancer and gynaecological cancer. Breast Care. 2008;3:417–422. doi: 10.1159/000177654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sellick SM, Edwardson AD. Screening new cancer patients for psychological distress using the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;16:534–542. doi: 10.1002/pon.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nieboer P, Buijs C, Rodenhuis S, et al. Fatigue and relating factors in high-risk breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant standard or high-dose chemotherapy: a longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8296–8304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, et al. Depression in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kissane DW, Bloch S, Smith GC, et al. Cognitive-existential group psychotherapy for women with primary breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2003;12:532–546. doi: 10.1002/pon.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gore-Felton C, Spiegel D. Group psychotherapy for medically ill patients. In: Stoudemire A, Fogel B, Greenberg D, editors. Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neises M. Psychological aspects of breast cancer. Breast Care. 2008;3:351–356. doi: 10.1159/000156906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert US, Wagner U, Kalder M. Breast Centers in Germany. Breast Care. 2009;4:225–230. doi: 10.1159/000231981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft e.V. (DKG) und Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG): Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie für die Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms. München, Zuckerschwerdt, 2008.

- 10.Reuter K, Weis J. Behandlung psychischer Belastungen und Störungen bei Tumorerkrankungen. In: Härter M, Bengel J, Baumeister H, editors. Psychische Störungen bei körperlichen Erkrankungen. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 125–13711. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Classen C, Butler LD, Koopman C, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a randomized clinical intervention trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:494–501. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I. Group support for patients with metastatic cancer. A randomized outcome study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:527–533. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780300039004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Classen C, Diamond S, Soleman A, et al.: Brief supportive-expressive group therapy for women with primary breast cancer: a treatment manual. Psychosocial Treatment Laboratory, Breast Cancer Intervention Project Stanford, Stanford University School of Medicine, 1993.

- 14.Spiegel D, Morrow GR, Classen C, et al. Group psychotherapy for recently diagnosed breast cancer patients: a multicenter feasibility study. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:482–493. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199911/12)8:6<482::aid-pon402>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiegel D, Classen C. A research-based handbook of psychosocial care. New York: Basic Books; 2000. Group therapy for cancer patients. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrmann C, Buss U, Snaith RP. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Deutsche Version. Bern: Huber; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sprangers M, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2756–2768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klauer T, Filipp SH. Trierer Skalen zur Krankheitsbewältigung. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt J, Wittmann WW. ZUF-8 Fragebogen zur Messung der Patientenzufriedenheit. In: Brähler E, Holling H, Leutner D, Petermann F, editors. Brickenkamp Handbuch psychologischer und pädagogischer Tests. Bd 2. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giese-Davis J, Spiegel D: Group Experiences Questionnaire. Unpublished Self-Report-Scale, 1995.

- 22.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hannöver W, Dogs CP, Kordy H. Patientenzufriedenheit – ein Maß für Behandlungserfolg? Psychotherapeut. 2000;45:292–300. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayring P. Kombination und Integration qualitativer und quantitativer Analyse. FQS Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung. 2001;2(1) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Classen CC, Kraemer HC, Blasey C, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy for primary breast cancer patients: a randomized prospective multicenter trial. Psychooncology. 2008;17:438–447. doi: 10.1002/pon.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer TJ, Mark MM. Effects of psychosocial interventions with adult cancer patients: a meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Health Psychol. 1995;14:101–108. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 1997;277:925–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]