Summary

Background

Ectopic breast tissue usually develops along the mammary ridges, and the incidence has been reported to be 2–6% of the general population. Occurrence of primary carcinoma in ectopic breast tissue is rare.

Case Report

We report the case of 59-year-old woman with accessory breast carcinoma in her left axilla.

Conclusion

Because an accessory areola or nipple is often missing and awareness of physicians and patients about these unsuspicious masses is lacking, clinical diagnosis of accessory breast carcinoma is frequently delayed. Therefore, a mass along the ‘milk line’ should be examined carefully, and any suspicious lesions should be evaluated.

Key Words: Accessory breast, Breast Cancer, Axilla

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Ektopisches Brustgewebe entwickelt sich gewöhnlich entlang der Milchleiste mit einer Inzidenz von 2–6% in der allgemeinen Bevölkerung. Das Auftreten primärer Karzinome in ektopischem Brustgewebe ist selten.

Fallbericht

Wir berichten von einer 59-jährigen Patientin mit einem Mammakarzinom in einer akzesso-rischen Brustdrüse in der linken Axilla.

Schlussfolgerung

Da akzessorische Warzenhöfe oder Brustwarzen zumeist nicht vorhanden sind und sowohl Ärzte als auch Patienten die meist unverdächtigen Knoten oft nicht zur Kenntnis nehmen, ist die klinische Diagnosestellung bei Mammakarzinomen akzessorischer Brustdrüsen regelmäßig verzögert. Ein Knoten entlang der Milchleiste sollte daher eingehend untersucht und verdächtige Läsionen genauer geprüft werden.

Introduction

Primary carcinoma of ectopic breast tissue has been reported only in a small number of cases. Overall, 94% of ectopic breast tumors occur in aberrant tissue and only 6% in accessory breasts [1,2,3]. Embryologically, ectopic breast tissue develops as a result of failed resolution of the mammary ridge, an ectodermal thickening that extends from the axilla to the external genitalia and has been found at sites as disparate as the axilla, labium, and the posterior thigh of a male patient [2, 4]. In the classification of ectopic breast tissue by Copeland and Geschickter [5], accessory nipple or areolar formation or both, with or without glandular tissue, is termed supernumerary breast, as opposed to aberrant tissue referring to ectopic breast tissue without a nipple or areolar complex. We named supernumerary breast as accessory breast.

Case Report

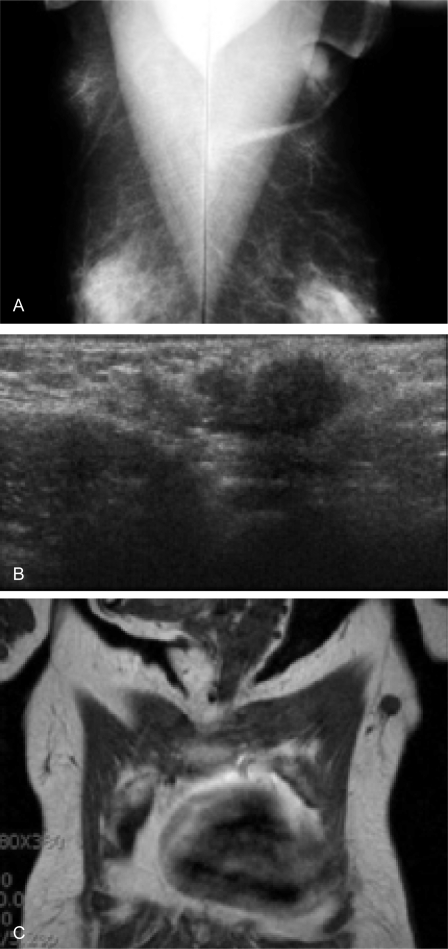

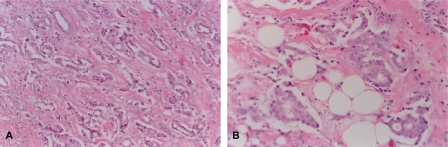

A 59-year-old female patient had noticed a painless lump in her left axillary area 1 month earlier. She was born with bilateral accessory nipples in the axilla. During the lactational period, milk was also released from the accessory nipple. She reported no previous menstrual irregularity, dysmenorrhea, or menorrhagia. The patient had received no estrogen therapy or oral contraceptive. There was no family history of breast carcinoma. Physical examination showed a non-tender, poorly defined mass measuring 2 cm in diameter and showing irregular margins (fig. 1). Routine hematological, biochemical parameters and tumor markers (carcinoembrionic antigen, CEA; cancer antigen, CA15-3) were within normal ranges. Chest X-ray, abdominal computed tomography, and 99mTc-MDP whole body bone scan were unremarkable. However, breast imaging findings were interpreted as suspicious for accessory breast carcinoma, and ultrasound-guided biopsy was recommended (fig. 2). Histological examination of the biopsy revealed invasive ductal carcinoma. The surgical option was a left accessory breast mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection. Pathological examination revealed a 1.7 × 1.5 × 1.5-cm tumor confined to the left accessory breast. The tumor was an invasive ductal carcinoma of histological grade 2/3 and nuclear grade 2/3, and 1 of 18 lymph nodes was positive for tumor (fig. 3). Estrogen and progesterone receptor proteins were positive and focal positive, respectively, and CerbB2 was negative by immunohistochemistry on paraffin sections. The postoperative treatment included chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, 5-fluor-ouracil, 6 cycles), radiotherapy of the axilla, and tamoxifen for 5 years. Her postoperative course was uneventful.

Fig. 1.

Accessory breast in the left axilla.

Fig. 2.

A Film Mammography shows an approximately 2.0-cm, lobulated mass with spiculated margin and pleomorphic, clustered microcalcifications in the left axilla. B Ultrasonography of the left axilla shows an approximately 1.7-cm, ill-defined, heterogenous, and hypoechoic mass with hyperechoic rim. C Breast magnetic resonance examination shows an approximately 1.7-cm, round, homogenous, and low signal intensity mass in the left axilla.

Fig. 3.

A Photomicrograph shows moderately differentiated invasive ductal carcinoma forming glandular structures (hematoxilin-eosin stain x100). B Photomicrograph shows tumor component invading surrounding mammary adipose tissue (hematoxilin-eosin stain x400).

Discussion

Ectopic breast tissue has been reported to occur in up to 6% of the population, more frequently in women and in the axilla [6]. Inheritance may be autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance, but sporadic cases represent the more common situation [7]. Accessory breasts appear most commonly along the original distribution of the mammary ridge which spans from the axilla to the groin; less commonly, accessory breasts appear in locations outside of the mammary ridge, such as the face, posterior neck, chest, middle back, buttock, vulva, flank, hip, posterior and/or lateral thigh, shoulder, and upper extremities [4, 8, 9, 10].

Primary breast carcinoma arising in accessory breasts of the axilla is the most common clinical presentation, with 60–70% of all ectopic breast tumors [1, 2, 11]. The most common pathology, as with the normal breast, is invasive ductal carcinoma [3]. There is no difference in diagnosis and symptoms of accessory breast carcinoma compared with carcinoma of the anatomic breast. The most common physical sign is a palpable mass. Edema, tenderness, breast pain, and vague discomfort are less often observed [12]. These tumors are diagnosed in the same manner as anatomic breast carcinoma using Mammography and ultrasonography, followed by pathologic diagnosis via fine needle aspiration cytology or gross excision [10]. Differential diagnosis includes excess axillary fat, lymphadenitis, lymphoma, metastatic carcinoma, and hydradenitis suppurativa [13].

Some authors have recommended radical mastectomy of the ipsilateral breast if the regional lymph nodes are diagnosed with carcinoma [14, 15]. However, Cogwells [16] has reported that ipsilateral mastectomy does not result in a better prognosis for ectopic breast carcinoma. Evans and Guyton [2] have concluded that ipsilateral mastectomy in addition to axillary lymph node dissection was not superior to local excision with node dissection. It has been proposed that the surgical procedure of choice in ectopic breast carcinoma is wide resection of the tumor with surrounding tissue, covering skin, and regional lymph nodes [1, 17]. Mastectomy is not indicated if clinical examination, mammography, and ultrasonography of the anatomic breast show no signs of disease, and should be performed when differential diagnosis is difficult [3, 15, 18]. If mastectomy is not performed, particularly careful follow-up is, of course, necessary to exclude any later manifestation of an occult primary neoplasm in the breast.

The principles of postoperative treatment are the same as for anatomic breast carcinoma [18]. External radiotherapy of the tumor site must be performed because it permits increased local control. However, radiation of the homolateral anatomic breast is not systematically performed [19]. Systemic adjuvant therapy is more frequently required because lymph node disease is usually found, and is performed following the same rules as with anatomic breast carcinoma [15, 19].

Prognosis of accessory breast carcinoma is equally difficult to establish, primarily due to absent or limited follow-up data as well as small sample size [2]. Moreover, it is difficult to find a clear histopathological and clinical distinction between accessory and anatomic breast carcinoma [15]. Some authors have proposed that accessory breast tissue is more prone to malignant change than normal breast parenchyma [20]. Others report that carcinoma of accessory breast tissue may metastasize to lymph nodes earlier and more frequently than with anatomic breast carcinoma [3, 19]. However, accessory breast carcinoma can be said to follow the same prognostic indices as anatomic breast carcinoma [1].

Conflict of Interest

The authors confirm that there was no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Marshall MB, Moynihan JJ, Frost A, Evans SR. Ectopic breast cancer: case report and literature review. Surg Oncol. 1994;3:295–304. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans DM, Guyton DP. Carcinoma of the axillary breast. J Surg Oncol. 1995;59:190–195. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930590311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yerra L, Karnad AB, Votaw ML. Primary breast cancer in aberrant breast tissue in the axilla. South Med J. 1997;90:661–662. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199706000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camisa C. Accessory breast on the posterior thigh of a man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:467–469. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(80)80110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Copeland MM, Geschickter CF. Symposium on diagnosis and treatment of premalignant conditions. Surg Clins N Am. 1950;30:1717–1741. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)33194-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutermuth J, Audring H, Voit C, Haas N. Primary carcinoma of ectopic axillary breast tissue. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:217–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loukas M, Clarke P, Tubbs RS. Accessory breasts: a historical and current perspective. Am Sur. 2007;73:525–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grossl NA. Supernumerary breast tissue: historical perspectives and clinical features. South Med J. 2000;93:29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanson E, Segovia J. Dorsal supernumerary breast. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61:441–445. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197803000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roorda AK, Hansen JP, Rider JA, Huang S, Rider DL. Ectopic breast cancer: special treatment considerations in the postmenopausal patient. Breast J. 2002;8:286–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2002.08507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amsler E, Sigal-Zafrani B, Marinho E, Aractingi S. Ectopic breast cancer of the axilla. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129:1389–1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardo M, Silva F, Jiménez P, Karmelic M. Mammary carcinoma in ectopic breast tissue. A case report. Rev Med Chil. 2001;129:663–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bland KI, Romrell LJ. Congenital and acquired disturbances of breast development and growth. In: Bland KI, Copeland EM 3rd, editors. The Breast: Comprehensive Management of Benign and Malignant Diseases. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tjalma WA, Senten LL. The management of ectopic breast cancer – case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2006;27:414–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakao A, Saito S, Inoue F, Notohara K, Tanaka N. Ectopic breast cancer: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:3737–3740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cogswell HD. Carcinoma of aberrant breast tissue. Am Surg. 1961;27:388–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livesey JR, Price BA. Metastatic accessory breast carcinoma in a thoracic subcutaneous nodule. J Royal Soc Med. 1990;83:799–800. doi: 10.1177/014107689008301215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markopoulos C, Kouskos E, Kontzoglou K, Gogas G, Kyriakou V, Gogas J. Breast cancer in ectopic breast tissue. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2001;22:157–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Routiot T, Marchal C, Verhaeghe JL, Depardieu C, Netter E, Weber B, Carolus JM. Breast carcinoma located in ectopic breast tissue: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Rep. 1998;5:413–417. doi: 10.3892/or.5.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Speert H. Supernumerary mammae with special reference to the rhesus monkey. The Quart Rev Biol. 1942;17:59–68. [Google Scholar]