Abstract

Aberrant DNA methylation commonly occurs in cancer cells where it has been implicated in the epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes. Additional roles for DNA methylation, such as transcriptional activation, have been predicted but have yet to be clearly demonstrated. The BCL6 oncogene is implicated in the pathogenesis of germinal center–derived B cell lymphomas. We demonstrate that the intragenic CpG islands within the first intron of the human BCL6 locus were hypermethylated in lymphoma cells that expressed high amounts of BCL6 messenger RNA (mRNA). Inhibition of DNA methyltransferases decreased BCL6 mRNA abundance, suggesting a role for these methylated CpGs in positively regulating BCL6 transcription. The enhancer-blocking transcription factor CTCF bound to this intronic region in a methylation-sensitive manner. Depletion of CTCF by short hairpin RNA in neoplastic plasma cells that do not express BCL6 resulted in up-regulation of BCL6 transcription. These data indicate that BCL6 expression is maintained during lymphomagenesis in part through DNA methylation that prevents CTCF-mediated silencing.

DNA methylation in mammals occurs on cytosine residues at the C5 position of the pyrimidine ring primarily at the palindromic dinucleotide sequence 5′-CG-3′ (Bestor, 1990; Lister et al., 2009). This covalent modification is essential for normal mammalian development (Li et al., 1992; Okano et al., 1999) and has been linked to transcriptional repression and formation of repressive chromatin structures on the underlying DNA (Jaenisch and Bird, 2003). DNA methylation is associated with imprinted regions, the inactive X chromosome, and parasitic DNA elements and their relics (Bestor, 2000; Lister et al., 2009). The role of DNA methylation in regulation of gene expression remains controversial (Bird, 1995; Bestor, 1998) but is generally thought to be associated with gene silencing.

CpG islands are genomic regions defined by a regional frequency of CG dinucleotides that approaches statistical expectations (Gardiner-Garden and Frommer, 1987). Presumably, this CG dinucleotide content is retained because these regions remain unmethylated in the germ line (Jones et al., 1992) or are subject to genetic selection (Rollins et al., 2006). These sequences are found in association with promoters in the human genome at high frequency (Saxonov et al., 2006). Their aberrant methylation in pathological processes is associated with loss of expression of the genes with which they are tightly linked (Feinberg et al., 2002). In mammalian cells, it is widely accepted that DNA methylation at promoter regions inhibits transcription initiation (Bird and Wolffe, 1999). In contrast, a body of evidence also indicates that the process of transcription elongation is largely refractory to DNA methylation in mammals (Robertson and Wolffe, 2000). A recent analysis of the methylation status of the X chromosome in female mammals indicated that DNA methylation levels were consistently higher within transcribed regions on the active allele compared with the inactive allele (Hellman and Chess, 2007). In this case, DNA methylation may serve to prevent activation of functional DNA elements (such as cryptic promoters, recombination hotspots, or transposable elements) embedded within transcription units (Jones, 1999).

In addition to its well documented roles in impacting local chromatin architecture, cytosine methylation serves to alter the chemistry of the major groove of DNA (Bird and Wolffe, 1999). The presence of additional functional groups in this location can serve to alter the binding of transcription factors to their cognate recognition elements. An example of such a factor is the CCCTC-binding factor CTCF (Lobanenkov et al., 1990), which binds DNA in a methylation-sensitive manner (Bell and Felsenfeld, 2000; Hark et al., 2000; Rodriguez et al., 2010). CTCF has unusual properties, exerting an influence on local chromatin architecture through the formation of higher order structures (Splinter et al., 2006). It also has the property, when located between a promoter and enhancer, of blocking enhancer function (Bell et al., 1999), potentially through its ability to organize chromosomal domains within the nucleus (Yusufzai et al., 2004). Therefore, DNA methylation has the potential to positively regulate gene transcription, albeit in an indirect manner, by preventing CTCF binding and thereby abolishing an enhancer block.

Aberrant DNA methylation has been observed in a wide range of cancer cells. Repetitive sequences within the intergenic regions of the genome, which are normally heavily methylated, often become hypomethylated in tumors (Feinberg et al., 1988). This global DNA hypomethylation is thought to contribute to genome instability during tumorigenesis (Howard et al., 2008). In contrast, promoter CpG islands are frequently hypermethylated and are strongly associated with transcriptional silencing (Costello et al., 2000; Rauch et al., 2008). Hypermethylation has been observed at promoters of various types of genes that can confer a growth advantage in tumors, encompassing tumor suppressor genes including VHL and RB1, cell cycle regulators such as p15INK4b and p16INK4a, DNA repair factors like BRCA1 and MLH1, and cell invasion/adhesion proteins such as E-cadherin (Boultwood and Wainscoat, 2007; McCabe et al., 2009). CpG islands outside of gene promoter regions in cancer cells have also been found to be hypermethylated, although their functional role in regulating gene expression is not clear (Weber et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2007). Although the role of DNA methylation in gene inactivation to promote tumorigenesis is well documented, a role for DNA methylation in gene activation, particularly of oncogenes, has yet to be clearly demonstrated.

The BCL6 (B cell lymphoma 6) oncogene was identified based on its involvement in translocations, placing its expression under the control of a strong enhancer in lymphoma (Ye et al., 1993a,b). The gene encodes a 95-kD protein, containing BTB/POZ and zinc finger motifs, that functions as a transcriptional repressor. In B lymphocytes, it is required for germinal center (GC) formation, which is the site of antibody affinity maturation in secondary lymphoid tissue (Ye et al., 1997). BCL6 is widely believed to restrain expression of the plasma cell transcriptional program before the initiation of terminal differentiation triggered by cell surface signaling events (Calame et al., 2003). Its deregulation is implicated in the pathogenesis of GC-derived diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL; Kusam and Dent, 2007). Mice engineered to express Bcl6 constitutively in B cells developed lymphomas with characteristics typical of human DLBCL (Cattoretti et al., 2005). Furthermore, sustained expression of BCL6 in DLBCLs is necessary for tumor survival and proliferation (Polo et al., 2004; Cerchietti et al., 2009b). Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms in regulating BCL6 expression has important implications in the identification of therapeutic targets for B cell lymphomas.

Constitutive BCL6 expression in a subset of DLBCLs occurs through chromosomal translocation or mutations in the promoter region of BCL6 (Ci et al., 2008). However, the majority of DLBCLs express BCL6 in the absence of genetic lesions (Ci et al., 2008). Therefore, additional regulatory mechanisms must be used in these DLBCLs to sustain BCL6 expression. Recently, it has been shown that the molecular chaperone Hsp90 can be up-regulated to stabilize and maintain BCL6 mRNA and protein in DLBCLs (Cerchietti et al., 2009a). In addition, epigenetic silencing of a microRNA targeting BCL6 also indirectly contributed to the maintenance of BCL6 expression in lymphomas (Saito et al., 2006). In this paper, we describe an unusual role for DNA methylation in the high level expression of BCL6 mRNA in lymphoma cells. Transcription of this protooncogene can be positively regulated by DNA methylation of intragenic CpG islands. This aberrant DNA methylation, specific to lymphoma, acted to prevent CTCF-mediated silencing of BCL6. These results provide a graphic example of aberrant DNA methylation in cancer serving to promote expression of an oncogene.

RESULTS

BCL6 transcription is initiated predominately at the upstream transcription initiation start site

BCL6 is located at human chromosome 3q27. The locus contains 11 exons, including two alternative noncoding first exons associated with two alternative transcription initiation sites. Both mRNA species code for identical proteins. We assessed steady-state levels of BCL6 mRNA in two model cell lines: Raji, a Burkitt lymphoma line with a transcriptional program similar to that of primary GC B cells (Epstein et al., 1966; Shaffer et al., 2002), and NCI-H929, a plasma cell myeloma cell line similar in many respects to primary plasma cells (Gazdar et al., 1986). By Northern analysis (Fig. S1 A) and by quantitative RT-PCR (not depicted), we detected high levels of BCL6 mRNA in Raji but were unable to detect the message in H929 above background levels.

Transcript mapping using publicly available expressed sequence tags (Kent et al., 2002) indicated the use of two transcription start sites at the human BCL6 locus that differ by roughly 9 kb. Both transcripts code for identical proteins, differing only in the sequences found in the alternative 5′ noncoding first exons. The biological functions of these noncoding exons, if any, remain unknown. In the current system, we analyzed utilization of the upstream versus downstream transcription start site by quantitative exon-specific RT-PCR (Fig. S1 B), finding that the vast majority of transcripts in Raji cells (>90%) initiate at the upstream start site (Fig. 1 A, locus map).

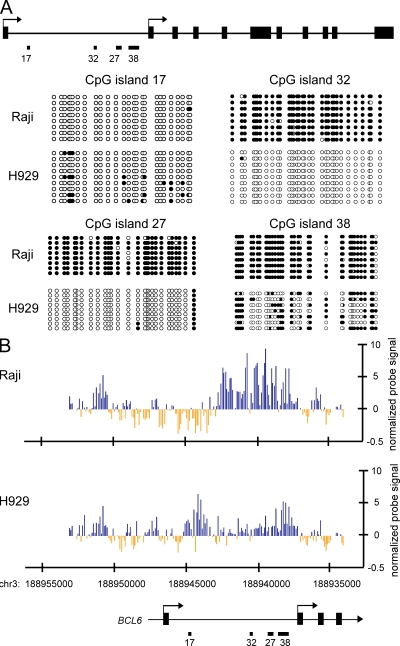

Figure 1.

Cell type–specific DNA methylation status at BCL6 intronic region. (A) The diagram depicts the genomic organization of the human BCL6 locus. Indicated are the two transcription start sites (arrows), the four CpG islands (17, 32, 27, and 38), and the exons (black rectangles). Below the cartoon, the results of genomic bisulfite sequencing are presented. Each line of circles indicates an individual clone sequenced in the analysis after bisulfite treatment and PCR. Open circles indicate CpG sites at which no DNA methylation is detected. Blackened circles indicate CpG sites which are methylated. Data shown is representative of the results of three independent biological replicates. (B) MIRA-chip analysis of Raji (top) and H929 (bottom) across the 5′ end of the BCL6 locus. Each vertical line represents the mean normalized log2 ratio of enriched/input probe signal from two replicate samples, corresponding to the genomic location on chromosome 3 at the BCL6 locus (UCSC genome browser HG18) as listed on the x axis. Blue and yellow colors represent methylated and unmethylated regions, respectively.

Differential DNA methylation status at BCL6 intronic CpG islands

Cytosine methylation is known to exert an influence on the transcriptional properties of DNA in mammals (Bestor, 2000; Jaenisch and Bird, 2003). Careful examination of the genomic context of human BCL6 (Fig. 1 A) revealed the presence of multiple CpG islands. As aberrant methylation of CpG islands is known to be associated with cancer (Laird, 2005; Baylin and Ohm, 2006), the methylation status of the CpG islands in Raji and H929 cell lines were determined by genomic bisulfite sequencing (Fig. 1 A). The most 5′ CpG island (CpG island 17) was almost completely unmethylated in both cell lines. CpG island 32 and CpG island 27, in contrast, were completely methylated in Raji and completely unmethylated in H929. CpG island 38 was methylated in both cell lines, with a marginally higher level of methylation in Raji.

To gain further insights into the DNA methylation status across the 5′ end of the BCL6 gene, we enriched for methylated DNA using the methylated CpG island recovery assay (MIRA; Rauch and Pfeifer, 2005; Rauch et al., 2006) in Raji and H929 and hybridized onto a DNA promoter tiling microarray. Using the MIRA-chip method, we obtained DNA methylation enrichment signal spanning from about −7 kb to +10 kb from the upstream transcription start site of BCL6, including the entire first intronic region of the gene at ∼150-bp resolution (Fig. 1 B). Consistent with the bisulfite sequencing data (Fig. 1 A), a peak-finding algorithm detected differential enrichment of methylated CpGs at the corresponding CpG islands in Raji and H929 (Fig. 1 B). In addition to robust enrichment of methylated CpGs at CpG islands 32, 27, and 38 in Raji, DNA methylation was present in the neighboring regions spreading along both ends of CpG island 32 (Fig. 1 B, top). H929 cells were enriched for methylated CpGs at CpG islands 17 and 38 but were devoid of DNA methylation in the entire region between these two CpG islands (Fig. 1 B, bottom). Bisulfite sequencing results indicated that CpG island 17 was only sparsely methylated in ∼50% of the alleles analyzed in H929 (Fig. 1 A). Nonetheless, this low density of methylated CpG in the region was detected as significant enrichment by MIRA-chip (Fig. 1 B, bottom), indicating a high sensitivity of this assay as previously reported (Rauch and Pfeifer, 2005). The MIRA-chip data were validated by quantitative PCR (Fig. S1 C), which demonstrated a strong correlation between the two detection methods. The hypermethylated status at the BCL6 intronic region in Raji cells suggested a possible role of DNA methylation in driving transcription of the gene.

Positive regulation of BCL6 transcription by DNA methylation

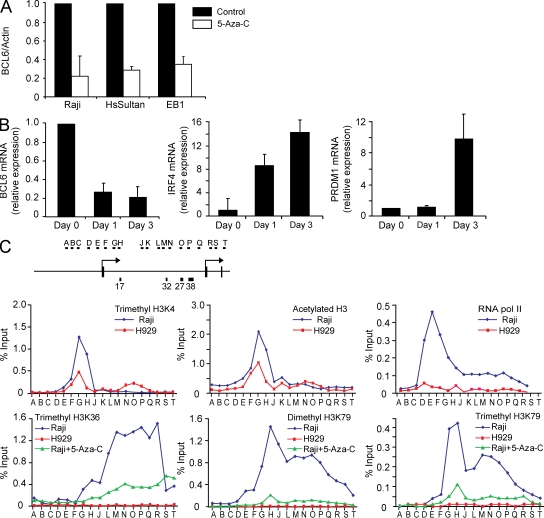

To ascertain whether DNA methylation might influence expression of BCL6 in this system, cells were treated with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza-C). Treatment of multiple Burkitt lymphoma and DLBCL cell lines with this drug led to a marked alteration in steady-state levels of BCL6 mRNA, as assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 2 A and Fig. S2 E). Inhibiting DNA methyltransferases led to three- to fivefold reductions in mRNA levels, which is consistent with a positive role for this epigenetic mark in regulation of the locus. Genomic bisulfite sequencing indicated that the transcriptional changes observed here were accompanied by alterations in the DNA methylation profiles at the intronic CpG islands (Fig. S2 A). Furthermore, consistent with the known role of BCL6 in specifying the identity of GC B lymphocytes (Kusam and Dent, 2007), treatment of Raji cells with 5-Aza-C led to increased steady-state levels of plasma cell–specific transcripts including PRDM1 and IRF4 (Fig. 2 B). In contrast to Raji, treatment with 5-Aza-C in H929 did not result in changes in BCL6 expression or up-regulation of IRF4 and PRDM1 transcripts (Fig. S2 B).

Figure 2.

Positive regulation of BCL6 transcription by DNA methylation. (A) The Raji, HsSultan, and EB1 Burkitt lymphoma cell lines were treated with 5-Aza-C for 24 h, and BCL6 and actin mRNA abundance was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. The bar graph depicts the BCL6 to actin ratio from three independent replicates. Error bars indicate standard deviation. The value from untreated cells for each replicate was arbitrarily set to 1. (B) Raji cells were treated with 5-Aza-C for the indicated times. BCL6, IRF4, and PRDM1 mRNA abundance was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. The bar graphs depict the ratio of each transcript to GAPDH mRNA, with the value from untreated cells (day 0) arbitrarily set to 1. Data represent the mean of three independent replicates. Error bars indicate standard deviation. (C) The diagram depicts the basic features of the BCL6 locus 5′ end along with the approximate locations of primer sets used to analyze the chromatin immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies in each panel. Each ChIP primer was analyzed by quantitative PCR with the graph depicting the percentage of input chromatin recovered in the immunoprecipitation for each primer set. The data represent the mean of two independent biological replicates.

It has been reported that genotoxic stress can lead to degradation of BCL6 protein (Phan et al., 2007), and 5-Aza-C treatment has been linked to induction of DNA damage (D’Incalci et al., 1985). To determine whether 5-Aza-C–mediated BCL6 down-regulation is not a result of DNA damage, Raji cells were treated with high (1 µM) and low (0.1 µM) nondamaging dosages of 5-Aza-C. Both concentrations of 5-Aza-C resulted in down-regulation of BCL6 transcript and protein level after 24 h of treatment (Figs. S2, C and D). Phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX), a sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage (Rogakou et al., 1998), did not accumulate after treatment of Raji with either dosage of 5-Aza-C (Fig. S2 D). In contrast, Raji cells treated with etoposide, a topoisomerase II inhibitor which induces DNA damage, readily up-regulated γH2AX phosphorylation (Fig. S2 D). Treatment of an independent cell line, the DLBCL cell line Su-DHL-6, with both high and low doses of 5-Aza-C resulted in reduction of BCL6 transcript level but only after 3 d of incubation in the presence of the drug (Fig. S2 E). We determined that this delayed BCL6 down-regulation was the result of a slower growth rate in Su-DHL-6 cells compared with Raji (Fig. S2 F). Collectively, these results indicate that the observed down-regulation of BCL6 was a consequence of DNA methyltransferase inhibition that is dependent on active cell division and not a consequence of DNA damage.

To further investigate whether the intronic DNA methylation directly regulates BCL6 transcription, we first examined several histone modifications that correlate with promoter chromatin accessibility or active transcription status across the BCL6 gene locus by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). PCR amplicons were designed to tile the human BCL6 locus at ∼500-bp intervals beginning upstream of the 5′ transcription start site and extending 3′ of the alternate transcription start site, spanning a genomic region of 15 kb (Fig. 2 C). First, the methylation status of histone H3 lysine (K) 4 and the acetylation status of histone H3 were analyzed across the 5′ end of the locus. The presence of both histone modifications at gene promoters is associated with genes either actively being transcribed or with the potential to be transcribed (Barski et al., 2007; Birney et al., 2007). Enrichment of both marks was observed just downstream of the transcription start site at the active locus in Raji (Fig. 2 C, top left and center), whereas the total histone H3 level remained constant throughout the 5′ end of the transcription unit (Fig. S2 G). At the inactive locus in H929, peaks for both marks were also observed near the transcription start site but at a lesser magnitude (Fig. 2 C, top left and center). In addition, a second peak of trimethyl H3K4 was observed in a region coincident with the differentially methylated CpG islands CpG 32 and CpG 27 (Fig. 2 C, top left) only in H929. These patterns of histone modification at the BCL6 locus are very consistent with the patterns observed in the human genome (Birney et al., 2007; Guenther et al., 2007; Heintzman et al., 2007)—notably, the presence of a sharp peak of active chromatin marks just downstream of the transcription start site of an actively transcribed gene.

The presence of the same marks—trimethyl H3K4 and acetyl H3—at the inactive locus in H929 suggests that the core promoter may be poised to fire in plasma cells despite the lack of detectable transcripts. However, despite the active chromatin conformation at the promoter of BCL6 in plasma cells, we did not observe enrichment of RNA polymerase II (Fig. 2 C, top right) or histone modifications that correlate with active transcription, such as trimethyl H3K36, dimethyl H3K79, and trimethyl H3K79 (Fig. 2 C, bottom), at the promoter or along the BCL6 gene in H929. In contrast, enrichment of these marks was readily detected throughout the transcription unit of BCL6 in Raji (Fig. 2 C, bottom). These results are consistent with the transcription status of BCL6 in the two cell types.

To further confirm a role of DNA methylation in directly regulating transcription of BCL6, we treated Raji with DNA methylation inhibitor 5-Aza-C for 72 h and assessed alterations in the histone modifications that correlate with transcriptional elongation. Although the level of trimethyl H3K4 did not decrease (Fig. S2 H), treatment of Raji with DNA methylation inhibitors led to dramatic reductions in the level and extent of all three elongation-associated modifications (trimethyl H3K36, dimethyl H3K79, and trimethyl H3K79), which is consistent with the loss of transcript (Fig. 2 C, bottom). These results strongly indicate that the presence of DNA methylation directly promotes the transcription of the BCL6 gene in lymphoma cell lines.

Presence of DNase I hypersensitive sites within CpG islands 32 and 27 in the absence of DNA methylation

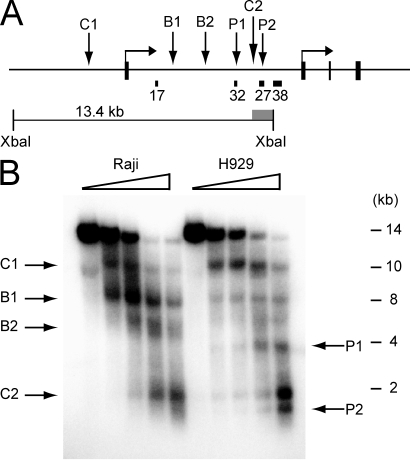

One of the proposed regulatory mechanisms ascribed to DNA methylation is to prevent the binding of transcription factors (Bird and Wolffe, 1999). DNase I hypersensitive site analysis was used to identify putative transcription factor binding sites within the human BCL6 locus in Raji and H929. We observed a complicated pattern of nuclease hypersensitivity at the locus that differed with cell type (Fig. 3). At the extreme 5′ end of the locus, we observed a hypersensitive site located ∼2 kb upstream of the transcription start site that was present in both Raji and H929 (site C1; Fig. 3 A, and B). We also identified a second constitutive hypersensitive site (site C2; Fig. 3, A and B) which mapped to the region between CpG islands 32 and 27 in the first intron. A series of additional hypersensitive sites at the 5′ end of the locus differed in intensity between the two cell types. Two sites (sites B1 and B2; Fig. 3, A and B) were present in both cell types but were more pronounced in Raji. Two other sites (sites P1 and P2; Fig. 3, A and B), coinciding with CpG islands 32 and 27, respectively, were apparent only in H929. Because sites P1 and P2 are not present in Raji where DNA methylation is detected, these sites could represent the presence of methylation-sensitive DNA binding factors.

Figure 3.

Presence of DNase I hypersensitive sites within CpG islands 32 and 27 in the absence of DNA methylation. (A) The diagram depicts the approximate location of the genomic features of the BCL6 locus along with the restriction fragments and probes used for indirect end labeling. The approximate locations of the observed hypersensitive sites are indicated on the diagram. (B) The 5′ end of the BCL6 locus was analyzed by DNase I digestion using the reference restriction enzyme XbaI. Wedges indicate concentrations of DNase I. The locations of restriction sites and the probe used for the Southern blot are depicted in A. Arrows indicate the major DNase I hypersensitive sites and their locations are summarized in A. Marker positions were measured from ethidium-stained gel before transfer. Data shown is representative of results from at least three independent experiments.

The remainder of the coding sequence was also analyzed. No hypersensitivity was observed in genomic DNA corresponding to a HindIII fragment covering the 3′ end of intron 1 through intron 4 (unpublished data). In contrast, the HindIII fragment covering a region from intron 4 to the 3′ UTR (Fig. S3, top) exhibited two diffuse hypersensitive regions that mapped toward the 3′ end of the transcription unit (sites C3 and C4; Fig. S3 A). DNase I analysis of the far 3′ end of the locus was also performed (Fig. S3, top). Two constitutive hypersensitive sites were observed (sites C5 and C6; Fig. S3 B). Thus, the human BCL6 locus presents a complex pattern of nuclease hypersensitivity marked by constitutive sites flanking the locus, cell type-specific sites within the 5′ end of the transcription unit, and additional constitutive sites within the 3′ end of the transcription unit.

CTCF binding at BCL6 negatively regulates its transcription

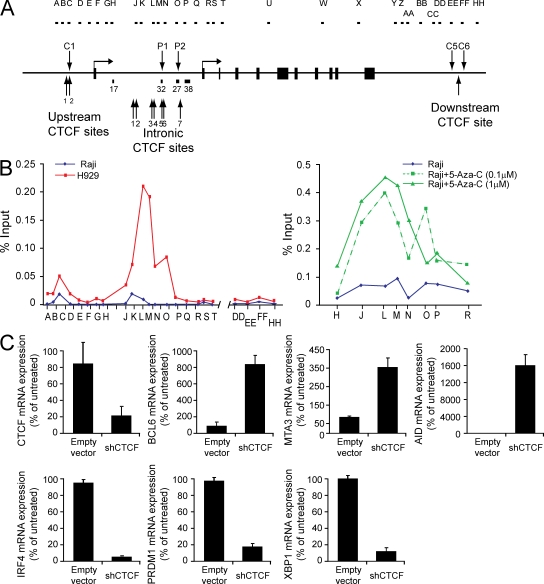

The presence of DNA methylation-sensitive DNase I hypersensitivity within the first intron of BCL6 was somewhat reminiscent of the situation at the mammalian H19/IGF2 locus, where CTCF is present to block enhancer activity at this imprinted locus (Bell and Felsenfeld, 2000; Hark et al., 2000). The presence of putative binding sites for CTCF at BCL6 was therefore analyzed in silico. ChIP data from a whole-genome analysis of CTCF binding (Kim et al., 2007) was used to identify putative CTCF sites in those loci. Using a motif discovery tool (Li, 2009), ∼11,000 CTCF binding sites (Fig. S4 B, motif logo) were identified in the 13721 ChIP-chip CTCF loci, from which a motif model (position weight matrix) was generated (Fig. S4 B). The model was subsequently used to scan for putative CTCF binding sites in the genomic DNA at BCL6. High score sites that are also conserved across a series of mammalian species are reported as putative CTCF binding sites. Two putative binding sites were observed at a region coincident with the 5′ constitutive hypersensitive site C1 (Fig. 4 A and Fig. S4 C). An additional predicted CTCF site colocalized with the 3′ constitutive hypersensitive sites C5/C6 (Fig. 4 A and Fig. S4 D). Multiple putative CTCF elements were found within intron 1. Most putative CTCF binding sites within the first intron of human BCL6 contain at least one CpG dinucleotide, presenting the opportunity for DNA methylation to modulate the interaction of CTCF with these regions of the genome (Fig. 4 A and Fig. S5). In general, sequence conservation across mammals is higher at the putative CTCF sites flanking the locus than at the individual intronic elements, implying a strict evolutionary requirement for maintenance of DNA sequence at those sites (Fig. S4, C and D; and Fig. S5).

Figure 4.

CTCF binding controls BCL6 expression. (A) The diagram depicts the genomic features of the BCL6 locus, including the locations of hypersensitive sites and the PCR amplicons used in the ChIP analysis. (B) The graph (left) depicts a representative example of CTCF ChIP at the BCL6 locus in Raji and H929. CTCF enrichment at intronic CTCF sites was also analyzed in Raji after 5-Aza-C treatment for 5 d (right). The graph represents mean enrichment levels from two experiments for each treatment condition. Data are presented as the percentage of input for each primer set, determined by quantitative PCR with comparison of immunoprecipitated DNA with a standard curve of DNA purified from input chromatin for each sample. (C) mRNA abundance in H929 cells treated with CTCF shRNA or empty vector was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data represent the mean of three independent replicates. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

Whether these putative sites were bound by CTCF was verified in two independent ways. First, these regions were analyzed in two publicly available datasets of CTCF localization in the human genome (Barski et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2007) assembled using different analysis techniques. In all cases, the putative CTCF binding sites identified in our analysis, including the intronic sites coinciding with the differentially methylated CpG islands, were sites of enrichment in these datasets. Importantly, cell types used for these analyses did not express BCL6. In addition, the occupancy of these sites by CTCF was determined experimentally by ChIP in our system (Fig. 4, A and B). In both Raji and H929, modest peaks of CTCF enrichment were observed at genomic regions coincident with the constitutive hypersensitive sites (sites C1 [primer set C] and C5/C6 [primer sets EE and FF]) flanking the locus. In H929, but not in Raji, we observed robust enrichment for CTCF across a region of intron 1 coinciding with the putative CTCF binding sites and with the differentially methylated CpG islands. Enrichment was highest at primer sets L and M which correspond roughly to predicted CTCF intronic sites (sites 3–6; Fig. 4, A and B). Another peak of substantial enrichment in the first intron (primer set O) correlated with an additional putative CTCF site (site 7; Fig. 4, A and B). As a test of our model of DNA methylation-regulated binding of CTCF at BCL6, we examined CTCF occupancy of these same sites in Raji cells treated with 5-Aza-C. We observed elevated CTCF occupancy at intronic sites 3–6 after 5-Aza-C treatment (Fig. 4 B), further demonstrating that DNA methylation serves as a regulator of CTCF binding at these sites.

The functional relevance to BCL6 expression of CTCF binding within the intronic region was probed by manipulation of CTCF expression levels. Lentiviral particles were prepared to deliver a short hairpin RNA designed to target CTCF and introduced into H929. After infection, cells were selected briefly for integration and live cells were purified for transcript analysis. RNA analysis indicated that depletion of CTCF transcript levels was accompanied by a corresponding increase in levels of BCL6 mRNA (Fig. 4 C). CTCF protein depletion in the presence of short hairpin (sh) RNA was also confirmed (Fig. S4 A). The level of BCL6 mRNA detected in H929 in the absence of CTCF is comparable to the level of BCL6 mRNA in B cell lines (Fig. 2, A and B), strongly implying that CTCF plays an active role in control of BCL6 expression. As BCL6 encodes a master regulator of the transcriptional program, we analyzed additional transcripts to ascertain whether CTCF depletion elicited alterations consistent with the action of BCL6. Transcript levels diagnostic (within the cell lines used) for GC identity including MTA3 and AID were elevated (Fig. 4 C). In contrast, transcript levels for multiple markers of the plasma cell transcriptional program, including IRF4, PRDM1, and XBP1, decreased after depletion of CTCF. These data are consistent with CTCF playing a key regulatory role at the BCL6 locus and, by extension, in the elaboration of cell type–specific transcription during the B cell to plasma cell transition.

Elevated DNA methylation at BCL6 intronic CTCF binding site in primary lymphoma cells

Next, we asked whether changes in intronic BCL6 DNA methylation status also occur in a similar fashion during the transition from GC B cell to plasma cell in an immune response. We performed genomic bisulfite sequencing analysis on BCL6 intronic CpG islands in primary human GC B cells and plasma cells isolated from tonsil. Little DNA methylation was detected at the intronic CpG islands in these cells (Fig. S6 A), indicating that the DNA methylation events described in this paper are likely to be either cancer or cell line associated.

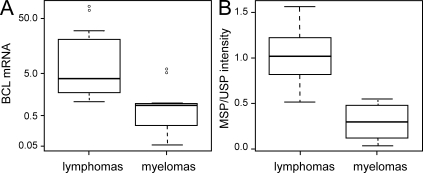

Accordingly, we investigated whether hypermethylation in BCL6 intronic region also occurs in primary lymphoma cells or if it is a cell line–specific phenomenon. Down-regulation of BCL6 expression can promote cell cycle arrest (Phan et al., 2005) and can reactivate the tumor suppressor gene p53 (Phan and Dalla-Favera, 2004); therefore, it is likely that lymphomas adapt regulatory mechanisms to ensure high expression of BCL6. To address this question, we compared the DNA methylation status at intronic CTCF sites within the BCL6 locus in a panel of B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and plasma cell myeloma samples, which express high and low levels of BCL6, respectively (Table S2, clinical data for lymphoma samples). The BCL6 transcript level in the two cancer cell types was determined by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5 A). The expression level of BCL6 in lymphoma samples was lower than that of Raji (Fig. 5 A), likely as a result of the heterogeneity of lymphoma samples (comprising both tumor and normal cell types). Despite this heterogeneity, we still detected significantly higher levels of BCL6 transcripts in lymphomas compared with myelomas (as determined by a one-tailed Student’s t test where P = 0.05; Fig. 5 A).

Figure 5.

DNA methylation analysis at CTCF binding sites in BCL6 intronic region of primary tumors. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of BCL6 mRNA abundance in lymphoma and plasma cell myeloma samples. The box-and-whisker plot illustrates the BCL6 expression level of 11 lymphoma and 8 myeloma samples as the percentage of expression level in Raji (y axis is plotted in log scale). The horizontal bar within the box represents the median (50th percentile) of the data points within each sample group, whereas the top and the bottom of the box represent the upper and lower quartile range (75th and 25th percentile), respectively. The whiskers represent the spread of data points within 1.5 interquartile range, and outliers are represented as open circles. (B) MSP analysis of CpGs at CTCF sites 3 and 4 in BCL6 intronic region. Intensities of 32P signal in the Southern blot of MSP and the corresponding unmethylated-specific PCR (USP) were quantified and represented as MSP/USP intensity ratio. MSP/USP primer locations and the CpGs being analyzed are shown in Fig. S6 B. The box-and-whisker plot compares the MSP/USP intensity ratio of the same lymphoma and myeloma samples analyzed in A.

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) was used to detect DNA methylation in the same tumor samples. We tested for the methylation status of CpGs at intronic CTCF sites 3, 4, and 5, where CTCF occupancy is highest by ChIP in H929 plasma cells (Fig. 4). Although a gain of CpG methylation signal at intronic site 5 was not detected (not depicted), we observed significantly higher signals of DNA methylation along the tandem CTCF sites 3 and 4 in lymphomas compared with the myelomas (as determined by a one-tailed Student’s t test where P = 5.53 × 10−6; Fig. 5 B). Differential methylation status at the CpG dinucleotides at CTCF sites 3 and 4 was also observed in Raji and H929 cells (Fig. S6 B and Fig. 1 B). Of the 11 lymphoma samples analyzed, only one sample had detectable level of translocation at the BCL6 locus (Fig. S6 C). This lymphoma sample had one of the lowest methylation signals at CTCF sites 3 and 4 (Fig. S6 D). This result supports the hypothesis that elevated DNA methylation is a mechanism that contributes to sustained high level transcription of BCL6 selectively in lymphomas that do not have translocation at the BCL6 locus. Altogether, the results from this paper demonstrate an intriguing new role for DNA methylation in transcriptional activation of an oncogene in cancer.

DISCUSSION

The role of DNA methylation in regulating gene expression has been extensively studied in the context of cancer, where aberrant accumulation of this epigenetic mark is strongly associated with transcriptional silencing of tumor suppressors (Feinberg et al., 2002; Jones, 2003; Baylin and Ohm, 2006). The data presented in this work provide evidence that aberrant DNA methylation in the context of cancer cells can also promote expression of an oncogene, BCL6. Presumably, the DNA methylation events described here serve to stabilize a functional chromatin state at the locus that excludes CTCF binding to intronic regulatory DNA and confers a growth advantage.

The regulatory mechanisms controlling transcription at the BCL6 locus are partially understood. BCL6 mRNA is expressed at high levels in GC B cells (Cattoretti et al., 1995; Onizuka et al., 1995) and its transcript levels are negatively controlled via autoregulatory elements in exon 1 and the first intron of the locus, sites of frequent mutation in lymphoma (Wang et al., 2002). IRF4 directly represses BCL6 expression during the transition from GC B cell to plasma cell, and by binding to regulatory DNA at the 5′ end of the transcription unit in a region that serves as a target for mutation in cancer (Saito et al., 2007). In this paper, we showed that gain of DNA methylation events at CTCF sites in the first intron of BCL6 are restricted to lymphomas and do not occur during normal B cell differentiation in the GC reaction (Fig. S6 A) when BCL6 expression is developmentally up-regulated. Our results suggest that DNA methylation acts in a cancer-specific manner to block access of CTCF to critical cis-acting regulatory DNA at BCL6 in a manner analogous to mutation of the BCL6 or IRF4 binding sites. It is likely that during a normal GC reaction, BCL6 transcription is activated in B lymphocytes, at least in part, through CTCF exclusion in a DNA methylation-independent mechanism mediated through extracellular signaling events (Lefevre et al., 2008). The gain of DNA methylation in B cell lymphomas may result from selective pressure to stably maintain BCL6 expression outside the GC microenvironment in the absence of the necessary extracellular stimuli.

We have observed differential binding of CTCF to conserved sites located in close proximity to, or contained within, the differentially methylated regions of intron 1. Binding of CTCF to these sites in plasma cells, but not in B cells, could lead to blockade of an enhancer element (Fig. S7 A), precisely as occurs at the imprinted H19/IGF2 locus (Bell and Felsenfeld, 2000; Hark et al., 2000). Alternatively, the presence of CTCF in the intronic BCL6 region can directly block transcription of the gene (Fig. S7 B) as previously described (Lobanenkov et al., 1990; Filippova et al., 1996). To our knowledge, this is the first example of differentially methylated CTCF binding sites located within the transcription unit they are proposed to regulate. This model of CTCF-regulated transcription is bolstered by depletion of CTCF by RNA interference in plasma cell lines, which leads to increased expression of BCL6 (Fig. 4 C) and alterations to the cellular transcriptional program consistent with a change in cell identity (Fig. 4 C).

Although this model explains the differential binding of CTCF to the BCL6 locus in these two cell types, it does not address the reason why BCL6 is regulated by such a complicated mechanism. The biology of genomic imprinting is embedded within evolutionary selective pressures that are not entirely understood (Tilghman, 1999; Reik and Lewis, 2005). That genes subject to complex patterns of expression, like imprinted genes, should have correspondingly complicated regulatory mechanisms is, perhaps, not surprising. BCL6, in contrast, presents an expression pattern reminiscent of many developmentally regulated genes. Transcription from the locus is maintained in a repressed state through much of development. There is a burst of activity in the developmental stage corresponding to the GC reaction, and then the gene is silenced concomitant with terminal differentiation to a plasma cell (Kusam and Dent, 2007). This pattern, OFF-ON-OFF, is recapitulated at many genes in multicellular organisms. However, two aspects of BCL6 biology suggest unique requirements for maintenance of a repressed state in most cell types. First, BCL6 functions as an oncogenic transcription factor (Melnick, 2005; Staudt and Dave, 2005). Second, high level expression of BCL6 leads to down-regulation of a set of genes integral to maintenance of genome integrity (Phan and Dalla-Favera, 2004; Ranuncolo et al., 2007). Sustained expression is sufficient to trigger lymphomagenesis, and experimental models have elegantly demonstrated this very point (Cattoretti et al., 2005). That the primary promoter used in B lymphocytes should be insulated by the action of CTCF in cells not participating in the GC reaction may be reflective of the inherent danger of expressing BCL6 protein at high levels.

The data presented in this work are consistent with a surprising role for DNA methylation in transcriptional regulation of an oncogene in cancer. Mechanistic predictions derived from these results suggest that, contrary to predominant models, DNA methylation likely contributes to transcriptional regulation in more than one capacity. The fundamental outcome of DNA methyltransferase activity is to alter the chemical properties and information content of the DNA major groove. We predict that evolution has used this information content to regulate multiple aspects of chromosomal biology, including transcriptional activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

All cell lines used in this work were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) with 10% FBS.

Nucleic acid extraction and manipulation

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomic DNA was extracted as previously described (Laird et al., 1991). cDNA was synthesized as previously described (Fujita et al., 2004). For genomic bisulfite sequencing, extracted DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite as previously described (Frommer et al., 1992). Primers used for RT-PCR and amplification of bisulfite converted DNA are listed in Table S1.

RNA analysis

For Northern analysis, total RNA was electrophoresed in agarose gels, transferred to Hybond-N+ membrane (GE Healthcare) and hybridized using ExpressHyb hybridization solution (Takara Bio Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The probe was labeled with α-[32P]dCTP using Prime-It RmT Random Primer Labeling kit (Agilent Technologies). The radiolabeled signals were detected using phosphor screen (GE Healthcare) and phosphor imager Storm 860 (Molecular Dynamics). Template DNA for random priming was prepared from a BCL6 cDNA clone (Fujita et al., 2004). The primers used are listed in Table S1.

MIRA-chip analysis

Genomic DNA purified from Raji and H929 were sonicated using a Bioruptor (Diagenode) to generate 200–500-bp fragments. Methylated CpG DNA fragments were enriched from 200 ng of sonicated DNA using the MethylCollector Ultra kit (Active Motif) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Input and methylated CpG DNA fragments were amplified (WGA2; Sigma-Aldrich), labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 random monomers (TriLink Biotechnologies), respectively, and hybridized onto a NimbleGen 2.1M Deluxe Human Promoter Array (Roche). Probe labeling, microarray hybridization, and processing were performed according to NimbleGen’s protocol. The microarray slides were scanned using a DNA microarray scanner (G2565BA; Agilent Technologies). Images were processed using the NimbleScan software. All microarray data files were deposited into GEO under accession no. GSE22884.

Data normalization.

A two-step normalization approach was used, where the first step is designed to correct for GC bias and dye bias within a chip (intrachip correction) and the second step corrects for variations across chips (interchip correction). The first step was within-chip normalization. First, all probes were binned according to their GC content. The GC content was computed as a ratio of C and G nucleotides to the total number of nucleotides in the probe sequence. The overall variability in GC content values was used to compute bin width according to zero-stage rule described in Wand (1997). These bin widths are proven to be approximate L2 optimal; i.e., they minimize mean integrated square error. The bins with fewer probes were then merged so that each bin contains at least 500 probes. Within each bin, Lowess regression (Cleveland et al., 1988; Hastie and Tibshirani, 1990) was used to predict log-transformed cy5 values as a smooth function of log-transformed cy3 values. The scaled (median of absolute residuals is used for scaling) difference between observed and predicted log(cy5) values were used as normalized signal.

The second step was between-chip normalization. Once the data were corrected for dye and GC bias as described in the first step, quantile normalization was used to correct for between sample variations. The resulting dataset was referred to as normalized data and was used for further investigations.

Identification of methylation sites across the genome.

A variant of the ACME algorithm (Scacheri et al., 2006) was used to identify peak regions. This algorithm depends on three user-specified tuning parameters: window size (w), signal threshold (s), and p-value threshold (p). Any probes in the data that are above threshold (s) are considered positive probes.

Enrichment p-value is computed using hyper geometric distribution by looking at observed number of positive probes (probes with signal > s) within a sliding window of size w centered on each probe as follows:

where N denotes total number of probes, K denotes total number of probes with signal > s (signal threshold defaults to 10th percentile), n denotes number of probes inside the sliding window of size w (defaults to 500), and x denotes number of probes inside the sliding window with signal > s.

Next, the binding sites are identified as runs of positive enrichment p-values, i.e., below threshold (default is p(x) < p). Each positive run of this sequence is considered to be a binding site. We do not correct the enrichment p-values for multiple comparisons, as they are only used as a means of finding regions of interest in the genome rather than a strict statistical significance level. The MIRA-chip data described in this paper have been deposited at the GEO database (GSE22884).

5-Aza-C and etoposide treatment

Cells were suspended at a density of 0.2 × 106 cell/ml and grown in normal culture media for 24 h. Cells were treated by addition of 0.1 or 1 µM 5-Sza-C (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24–72 h. For etoposide treatment in Raji, cells were treated with either 5 µM etoposide (Sigma-Aldrich) or equal volume of DMSO as vehicle control for 24 h. To analyze Bcl6 and phosphorylated H2A.X protein level, cells were harvested and lysed in 1 M Tris, pH 6.8, with 8 M urea and 1% SDS for SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed using anti-Bcl6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; sc-858), anti–γ-H2AX (Millipore; 05–636), and anti-actin (Millipore; MAB1501).

ChIP assay

For histone modifications and RNA Polymerase II, 107 cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde in PBS and incubated 10 min at room temperature. For CTCF, cells were incubated 15 min at room temperature. In all cases, cross-linking was terminated by addition of glycine. The cells were spun down and rinsed in ice-cold PBS three times. The cell lysates were sonicated using a Bioruptor (Diagenode) to generate 300–500 bp (histone modification mapping, RNA polymerase II) or 500–4,000-bp DNA fragments (CTCF mapping) for immunoprecipitation. The following antibodies were used for ChIP: total H3 (Millipore), acetylated H3 (Millipore), trimethyl K4 (Millipore), CTCF (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.), RNA polymerase II (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), trimethyl K36 (Abcam), dimethyl K79 (Abcam), and trimethyl K79 (Abcam). Primer sets used for ChIP experiments are listed in Table S1.

DNase I hypersensitivity

Nuclei were extracted from 2 × 108 cells using a sucrose pad and divided into 600-µg DNA aliquots. CaCl2 and MgCl2 were added to the aliquots in a final concentration of 1 mM. The samples were treated with the following amounts of DNase I: 0, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 µg for 9 min at 37°C. The DNase I digestion was stopped by using 300 µl of the stop solution (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.6 M NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, and 500 µg/ml proteinase K) at 55°C over night. The digested DNA was phenol/chloroform extracted and precipitated with isopropanol. DNA pellet was dissolved in water and was digested with the Southern blot reference enzyme. 20 µg of digested DNA per lane was transferred to the Hybond-N+ membrane (GE Healthcare). Blots were probed with the appropriate α-[32P]dCTP–labeled PCR product. The primer sequences used for generating the probes are listed in Table S1.

shRNA-mediated depletion of CTCF

pLKO.1-shCTCF (TRCN0000014551) and pLKO.1 empty lentiviral vectors were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Lentivirus was packaged in 293T cells by transfecting lentiviral vector along with psPAX2 and pMD2.G plasmids. Supernatant from transfected 293T cultures containing lentiviral particles were collected at 48 and 72 h after transfection. Lentivirus supernatant was added to H929 culture for infection in the presence of 8 µg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). After 48 h of culture, lentiviral-infected H929 cells were selected with puromycin (1 µg/ml) for an additional 3 d. Dead cells were excluded from analyses by FACS sorting of cells that do not stain positively with propidium iodide. To evaluate CTCF protein level in shCTCF knockdown cells, shCTCF or empty lentiviral vectors were transfected into 293T cells for 3 d. Cells were harvested and lysed with 1 M Tris, pH 6.8, with 8 M urea and 1% SDS for SDS-PAGE. Western blot was performed using anti-CTCF (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.; A300-544A) and anti-actin (Millipore; MAB1501).

Analysis of primary tumor samples

Cryopreserved lymphoma and myeloma samples were obtained from the Department of Pathology and the Hematology Tissue Acquisition and Banking Service at the Winship Cancer Institute at Emory University supported by the Georgia Cancer Coalition. This study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board Biomedical Committee.

Genomic DNA and total RNA were copurified using the DNA/RNA Isolation kit (QIAGEN). First-strand cDNA synthesis and quantitative RT-PCR of BCL6 were performed as described in RNA analysis. The expression level of BCL6 was normalized to GAPDH housekeeping gene level and is represented as a percentage to the expression level of Raji. To analyze DNA methylation at the BCL6 locus, genomic DNA from tumor samples were bisulfite treated using the EZ DNA Methylation Gold kit (Zymo Research). After 25 cycles of PCR, amplified products were resolved on an agarose gel and transferred onto Hybond-N+ membrane (GE Healthcare) for Southern blot analysis as described above. PCR product amplified from bisulfite-treated Raji DNA was radiolabeled and used as probe for Southern blot hybridization. The ImageQuant software was used to quantify the intensities of the DNA bands. Comparison of relative DNA methylation levels in lymphomas and myelomas was performed by calculating the ratio of MSP/USP band intensity from each individual tumor sample. Primers used for MSP/USP analyses are listed in Table S1. Analysis of BCL6 translocation status was performed according to the method described by Lossos et al. (2003).

Isolation of tonsillar B cells

Fresh human tonsil was obtained from the Emory University Pathology service. Appropriate institutional (IRB) approvals were obtained. Primary GC B cells and plasma cells were purified as previously described (Cattoretti et al., 2006) with modifications. Tonsil specimens were processed into single cell suspension in PBS, followed by mononuclear cell isolation using a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. Tonsillar mononuclear cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in PBS with 2% FBS and 0.02% NaN3. T cells were depleted by incubating sample with purified mouse anti–human CD4 (clone OKT4; eBioscience) and anti-CD8 (clone OKT8; eBioscience) antibodies, followed by sheep anti–mouse IgG Dynal beads (Invitrogen). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were then removed by magnetic separation. T cell–depleted tonsillar mononuclear cells were subsequently stained with the following monoclonal antibodies for FACS purification: PE-IgD (BD), PECy7-CD38 (clone HIT2; eBioscience), and Pacific blue–CD20 (clone 2H7; eBioscience). Cell sortings were performed using a FACSVantage (BD) with Digital Option. GC B cells were defined as CD20+CD38+IgD− cells, and plasma cells were defined as CD20loCD38hiIgD− cells.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows BCL6 mRNA transcript analysis in cell lines and validation of MIRA-chip data by PCR. Fig. S2 shows effects of 5-Aza-C treatment in BCL6 expressions in cell lines. Fig. S3 shows additional DNase I hypersensitivity sites identified at 3′ end of BCL6. Fig. S4 shows depletion of CTCF protein in shCTCF transfected cells and predicted CTCF binding sites within BCL6 locus. Fig. S5 shows intronic CTCF binding sites at BCL6. Fig. S6 shows DNA methylation analysis at CTCF binding sites and BCL6 translocation status in primary lymphoma cells. Fig. S7 shows a possible mechanism of CTCF-mediated transcriptional silencing of BCL6. Table S1 shows primer sequences used for all experiments. Table S2 shows clinical data for primary lymphoma samples used in this study. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20100204/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the members of the Wade, Archer, and Adelman laboratories for many useful discussions and comments in the course of this work. This manuscript was substantially improved by critical comments from Trevor Archer, Tom Eling, and Harriet Kinyamu. We also thank Drs. Jeff Tucker, Daniel Gilchrist, Scott Norton, Kevin Gerrish, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences microarray facility for their assistance in MIRA-chip experiments.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health (Project number Z01ES101965 to P.A. Wade, Project number Z01ES101765 to L. Li) and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK60647 to D.L. Jaye). D. Mav and R. Shah were supported in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Delivery Order Number HHSN291200555547C, GSA Contract Number GS-00F-003L.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- 5-Aza-C

- 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DLBCL

- diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- GC

- germinal center

- MIRA

- methylated CpG island recovery assay

- MSP

- methylation-specific PCR

- USP

- unmethylated-specific PCR

References

- Barski A., Cuddapah S., Cui K., Roh T.Y., Schones D.E., Wang Z., Wei G., Chepelev I., Zhao K. 2007. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 129:823–837 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylin S.B., Ohm J.E. 2006. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer - a mechanism for early oncogenic pathway addiction? Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6:107–116 10.1038/nrc1799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell A.C., Felsenfeld G. 2000. Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature. 405:482–485 10.1038/35013100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell A.C., West A.G., Felsenfeld G. 1999. The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell. 98:387–396 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81967-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor T.H. 1990. DNA methylation: evolution of a bacterial immune function into a regulator of gene expression and genome structure in higher eukaryotes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 326:179–187 10.1098/rstb.1990.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor T.H. 1998. The host defence function of genomic methylation patterns. Novartis Found. Symp. 214:187–195, discussion :195–199: 228–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor T.H. 2000. The DNA methyltransferases of mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9:2395–2402 10.1093/hmg/9.16.2395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A.P. 1995. Gene number, noise reduction and biological complexity. Trends Genet. 11:94–100 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)89009-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A.P., Wolffe A.P. 1999. Methylation-induced repression—belts, braces, and chromatin. Cell. 99:451–454 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81532-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A., Dutta A., Guigó R., Gingeras T.R., Margulies E.H., Weng Z., Snyder M., Dermitzakis E.T., Thurman R.E., et al. ; ENCODE Project Consortium; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center; Washington University Genome Sequencing Center; Broad Institute; Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute 2007. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 447:799–816 10.1038/nature05874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boultwood J., Wainscoat J.S. 2007. Gene silencing by DNA methylation in haematological malignancies. Br. J. Haematol. 138:3–11 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calame K.L., Lin K.I., Tunyaplin C. 2003. Regulatory mechanisms that determine the development and function of plasma cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:205–230 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattoretti G., Chang C.C., Cechova K., Zhang J., Ye B.H., Falini B., Louie D.C., Offit K., Chaganti R.S., Dalla-Favera R. 1995. BCL-6 protein is expressed in germinal-center B cells. Blood. 86:45–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattoretti G., Pasqualucci L., Ballon G., Tam W., Nandula S.V., Shen Q., Mo T., Murty V.V., Dalla-Favera R. 2005. Deregulated BCL6 expression recapitulates the pathogenesis of human diffuse large B cell lymphomas in mice. Cancer Cell. 7:445–455 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattoretti G., Shaknovich R., Smith P.M., Jäck H.M., Murty V.V., Alobeid B. 2006. Stages of germinal center transit are defined by B cell transcription factor coexpression and relative abundance. J. Immunol. 177:6930–6939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerchietti L.C., Lopes E.C., Yang S.N., Hatzi K., Bunting K.L., Tsikitas L.A., Mallik A., Robles A.I., Walling J., Varticovski L., et al. 2009a. A purine scaffold Hsp90 inhibitor destabilizes BCL-6 and has specific antitumor activity in BCL-6-dependent B cell lymphomas. Nat. Med. 15:1369–1376 10.1038/nm.2059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerchietti L.C., Yang S.N., Shaknovich R., Hatzi K., Polo J.M., Chadburn A., Dowdy S.F., Melnick A. 2009b. A peptomimetic inhibitor of BCL6 with potent antilymphoma effects in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 113:3397–3405 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ci W., Polo J.M., Melnick A. 2008. B-cell lymphoma 6 and the molecular pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 15:381–390 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328302c7df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland W.S., Devlin S.J., Grosse E. 1988. Regression by local fitting. J. Econom. 37:87–114 10.1016/0304-4076(88)90077-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costello J.F., Frühwald M.C., Smiraglia D.J., Rush L.J., Robertson G.P., Gao X., Wright F.A., Feramisco J.D., Peltomäki P., Lang J.C., et al. 2000. Aberrant CpG-island methylation has non-random and tumour-type-specific patterns. Nat. Genet. 24:132–138 10.1038/72785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Incalci M., Covey J.M., Zaharko D.S., Kohn K.W. 1985. DNA alkali-labile sites induced by incorporation of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine into DNA of mouse leukemia L1210 cells. Cancer Res. 45:3197–3202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M.A., Achong B.G., Barr Y.M., Zajac B., Henle G., Henle W. 1966. Morphological and virological investigations on cultured Burkitt tumor lymphoblasts (strain Raji). J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 37:547–559 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A.P., Gehrke C.W., Kuo K.C., Ehrlich M. 1988. Reduced genomic 5-methylcytosine content in human colonic neoplasia. Cancer Res. 48:1159–1161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A.P., Oshimura M., Barrett J.C. 2002. Epigenetic mechanisms in human disease. Cancer Res. 62:6784–6787 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippova G.N., Fagerlie S., Klenova E.M., Myers C., Dehner Y., Goodwin G., Neiman P.E., Collins S.J., Lobanenkov V.V. 1996. An exceptionally conserved transcriptional repressor, CTCF, employs different combinations of zinc fingers to bind diverged promoter sequences of avian and mammalian c-myc oncogenes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:2802–2813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommer M., McDonald L.E., Millar D.S., Collis C.M., Watt F., Grigg G.W., Molloy P.L., Paul C.L. 1992. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:1827–1831 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita N., Jaye D.L., Geigerman C., Akyildiz A., Mooney M.R., Boss J.M., Wade P.A. 2004. MTA3 and the Mi-2/NuRD complex regulate cell fate during B lymphocyte differentiation. Cell. 119:75–86 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner-Garden M., Frommer M. 1987. CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 196:261–282 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90689-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdar A.F., Oie H.K., Kirsch I.R., Hollis G.F. 1986. Establishment and characterization of a human plasma cell myeloma culture having a rearranged cellular myc proto-oncogene. Blood. 67:1542–1549 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther M.G., Levine S.S., Boyer L.A., Jaenisch R., Young R.A. 2007. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 130:77–88 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hark A.T., Schoenherr C.J., Katz D.J., Ingram R.S., Levorse J.M., Tilghman S.M. 2000. CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature. 405:486–489 10.1038/35013106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T.J., Tibshirani R.J. 1990. Generalized Additive Models. Chapman & Hall, New York: 356 pp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintzman N.D., Stuart R.K., Hon G., Fu Y., Ching C.W., Hawkins R.D., Barrera L.O., Van Calcar S., Qu C., Ching K.A., et al. 2007. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 39:311–318 10.1038/ng1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman A., Chess A. 2007. Gene body-specific methylation on the active X chromosome. Science. 315:1141–1143 10.1126/science.1136352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard G., Eiges R., Gaudet F., Jaenisch R., Eden A. 2008. Activation and transposition of endogenous retroviral elements in hypomethylation induced tumors in mice. Oncogene. 27:404–408 10.1038/sj.onc.1210631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenisch R., Bird A. 2003. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat. Genet. 33(Suppl):245–254 10.1038/ng1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P.A. 1999. The DNA methylation paradox. Trends Genet. 15:34–37 10.1016/S0168-9525(98)01636-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P.A. 2003. Epigenetics in carcinogenesis and cancer prevention. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 983:213–219 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb05976.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P.A., Rideout W.M., III, Shen J.C., Spruck C.H., Tsai Y.C. 1992. Methylation, mutation and cancer. Bioessays. 14:33–36 10.1002/bies.950140107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W.J., Sugnet C.W., Furey T.S., Roskin K.M., Pringle T.H., Zahler A.M., Haussler D. 2002. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12:996–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.H., Abdullaev Z.K., Smith A.D., Ching K.A., Loukinov D.I., Green R.D., Zhang M.Q., Lobanenkov V.V., Ren B. 2007. Analysis of the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF-binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 128:1231–1245 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusam S., Dent A. 2007. Common mechanisms for the regulation of B cell differentiation and transformation by the transcriptional repressor protein BCL-6. Immunol. Res. 37:177–186 10.1007/BF02697368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird P.W. 2005. Cancer epigenetics. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14(Spec No 1):R65–R76 10.1093/hmg/ddi113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird P.W., Zijderveld A., Linders K., Rudnicki M.A., Jaenisch R., Berns A. 1991. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:4293 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefevre P., Witham J., Lacroix C.E., Cockerill P.N., Bonifer C. 2008. The LPS-induced transcriptional upregulation of the chicken lysozyme locus involves CTCF eviction and noncoding RNA transcription. Mol. Cell. 32:129–139 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. 2009. GADEM: a genetic algorithm guided formation of spaced dyads coupled with an EM algorithm for motif discovery. J. Comput. Biol. 16:317–329 10.1089/cmb.2008.16TT [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E., Bestor T.H., Jaenisch R. 1992. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 69:915–926 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R., Pelizzola M., Dowen R.H., Hawkins R.D., Hon G., Tonti-Filippini J., Nery J.R., Lee L., Ye Z., Ngo Q.M., et al. 2009. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 462:315–322 10.1038/nature08514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobanenkov V.V., Nicolas R.H., Adler V.V., Paterson H., Klenova E.M., Polotskaja A.V., Goodwin G.H. 1990. A novel sequence-specific DNA binding protein which interacts with three regularly spaced direct repeats of the CCCTC-motif in the 5′-flanking sequence of the chicken c-myc gene. Oncogene. 5:1743–1753 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossos I.S., Akasaka T., Martinez-Climent J.A., Siebert R., Levy R. 2003. The BCL6 gene in B-cell lymphomas with 3q27 translocations is expressed mainly from the rearranged allele irrespective of the partner gene. Leukemia. 17:1390–1397 10.1038/sj.leu.2402997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe M.T., Brandes J.C., Vertino P.M. 2009. Cancer DNA methylation: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 15:3927–3937 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick A. 2005. Reprogramming specific gene expression pathways in B-cell lymphomas. Cell Cycle. 4:239–241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano M., Bell D.W., Haber D.A., Li E. 1999. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell. 99:247–257 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81656-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onizuka T., Moriyama M., Yamochi T., Kuroda T., Kazama A., Kanazawa N., Sato K., Kato T., Ota H., Mori S. 1995. BCL-6 gene product, a 92- to 98-kD nuclear phosphoprotein, is highly expressed in germinal center B cells and their neoplastic counterparts. Blood. 86:28–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan R.T., Dalla-Favera R. 2004. The BCL6 proto-oncogene suppresses p53 expression in germinal-centre B cells. Nature. 432:635–639 10.1038/nature03147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan R.T., Saito M., Basso K., Niu H., Dalla-Favera R. 2005. BCL6 interacts with the transcription factor Miz-1 to suppress the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 and cell cycle arrest in germinal center B cells. Nat. Immunol. 6:1054–1060 10.1038/ni1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan R.T., Saito M., Kitagawa Y., Means A.R., Dalla-Favera R. 2007. Genotoxic stress regulates expression of the proto-oncogene Bcl6 in germinal center B cells. Nat. Immunol. 8:1132–1139 10.1038/ni1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo J.M., Dell’Oso T., Ranuncolo S.M., Cerchietti L., Beck D., Da Silva G.F., Prive G.G., Licht J.D., Melnick A. 2004. Specific peptide interference reveals BCL6 transcriptional and oncogenic mechanisms in B-cell lymphoma cells. Nat. Med. 10:1329–1335 10.1038/nm1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranuncolo S.M., Polo J.M., Dierov J., Singer M., Kuo T., Greally J., Green R., Carroll M., Melnick A. 2007. Bcl-6 mediates the germinal center B cell phenotype and lymphomagenesis through transcriptional repression of the DNA-damage sensor ATR. Nat. Immunol. 8:705–714 10.1038/ni1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch T., Pfeifer G.P. 2005. Methylated-CpG island recovery assay: a new technique for the rapid detection of methylated-CpG islands in cancer. Lab. Invest. 85:1172–1180 10.1038/labinvest.3700311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch T., Li H., Wu X., Pfeifer G.P. 2006. MIRA-assisted microarray analysis, a new technology for the determination of DNA methylation patterns, identifies frequent methylation of homeodomain-containing genes in lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 66:7939–7947 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch T.A., Zhong X., Wu X., Wang M., Kernstine K.H., Wang Z., Riggs A.D., Pfeifer G.P. 2008. High-resolution mapping of DNA hypermethylation and hypomethylation in lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:252–257 10.1073/pnas.0710735105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik W., Lewis A. 2005. Co-evolution of X-chromosome inactivation and imprinting in mammals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6:403–410 10.1038/nrg1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson K.D., Wolffe A.P. 2000. DNA methylation in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 1:11–19 10.1038/35049533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C., Borgel J., Court F., Cathala G., Forné T., Piette J. 2010. CTCF is a DNA methylation-sensitive positive regulator of the INK/ARF locus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 392:129–134 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou E.P., Pilch D.R., Orr A.H., Ivanova V.S., Bonner W.M. 1998. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J. Biol. Chem. 273:5858–5868 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins R.A., Haghighi F., Edwards J.R., Das R., Zhang M.Q., Ju J., Bestor T.H. 2006. Large-scale structure of genomic methylation patterns. Genome Res. 16:157–163 10.1101/gr.4362006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y., Liang G., Egger G., Friedman J.M., Chuang J.C., Coetzee G.A., Jones P.A. 2006. Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 9:435–443 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M., Gao J., Basso K., Kitagawa Y., Smith P.M., Bhagat G., Pernis A., Pasqualucci L., Dalla-Favera R. 2007. A signaling pathway mediating downregulation of BCL6 in germinal center B cells is blocked by BCL6 gene alterations in B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 12:280–292 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxonov S., Berg P., Brutlag D.L. 2006. A genome-wide analysis of CpG dinucleotides in the human genome distinguishes two distinct classes of promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:1412–1417 10.1073/pnas.0510310103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scacheri P.C., Crawford G.E., Davis S. 2006. Statistics for ChIP-chip and DNase hypersensitivity experiments on NimbleGen arrays. Methods Enzymol. 411:270–282 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11014-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer A.L., Lin K.I., Kuo T.C., Yu X., Hurt E.M., Rosenwald A., Giltnane J.M., Yang L., Zhao H., Calame K., Staudt L.M. 2002. Blimp-1 orchestrates plasma cell differentiation by extinguishing the mature B cell gene expression program. Immunity. 17:51–62 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00335-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.F., Mahmood S., Song F., Morrow A., Smiraglia D., Zhang X., Rajput A., Higgins M.J., Krumm A., Petrelli N.J., et al. 2007. Identification of DNA methylation in 3′ genomic regions that are associated with upregulation of gene expression in colorectal cancer. Epigenetics. 2:161–172 10.4161/epi.2.3.4805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splinter E., Heath H., Kooren J., Palstra R.J., Klous P., Grosveld F., Galjart N., de Laat W. 2006. CTCF mediates long-range chromatin looping and local histone modification in the beta-globin locus. Genes Dev. 20:2349–2354 10.1101/gad.399506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt L.M., Dave S. 2005. The biology of human lymphoid malignancies revealed by gene expression profiling. Adv. Immunol. 87:163–208 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)87005-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilghman S.M. 1999. The sins of the fathers and mothers: genomic imprinting in mammalian development. Cell. 96:185–193 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80559-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand M.P. 1997. Data-Based Choice of Histogram Bin Width. Am. Stat. 51:59–64 10.2307/2684697 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Li Z., Naganuma A., Ye B.H. 2002. Negative autoregulation of BCL-6 is bypassed by genetic alterations in diffuse large B cell lymphomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:15018–15023 10.1073/pnas.232581199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M., Davies J.J., Wittig D., Oakeley E.J., Haase M., Lam W.L., Schübeler D. 2005. Chromosome-wide and promoter-specific analyses identify sites of differential DNA methylation in normal and transformed human cells. Nat. Genet. 37:853–862 10.1038/ng1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye B.H., Lista F., Lo Coco F., Knowles D.M., Offit K., Chaganti R.S., Dalla-Favera R. 1993a. Alterations of a zinc finger-encoding gene, BCL-6, in diffuse large-cell lymphoma. Science. 262:747–750 10.1126/science.8235596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye B.H., Rao P.H., Chaganti R.S., Dalla-Favera R. 1993b. Cloning of bcl-6, the locus involved in chromosome translocations affecting band 3q27 in B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Res. 53:2732–2735 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye B.H., Cattoretti G., Shen Q., Zhang J., Hawe N., de Waard R., Leung C., Nouri-Shirazi M., Orazi A., Chaganti R.S., et al. 1997. The BCL-6 proto-oncogene controls germinal-centre formation and Th2-type inflammation. Nat. Genet. 16:161–170 10.1038/ng0697-161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusufzai T.M., Tagami H., Nakatani Y., Felsenfeld G. 2004. CTCF tethers an insulator to subnuclear sites, suggesting shared insulator mechanisms across species. Mol. Cell. 13:291–298 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00029-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]