Abstract

Objective

To assess the value of a faculty and resident medical education development program.

Study Design

Modules on Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies and evaluation, teaching methods, and Residency Review Committee guidelines were created, beta tested, and installed on a website. Pretests and posttests were developed. Faculty and residents were required to complete the course. At initiation and 6 months after training, residents completed a feedback perception survey. Statistical analysis was performed using Student t test. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Forty-nine voluntary faculty members and residents completed the course. The posttest scores on all the ACGME competencies were significantly higher than the pretest scores (P < .05). The results of the residents' survey indicated that the educational development program significantly improved their perceptions of corrective and immediate feedback by faculty.

Conclusion

A formal Internet-based program significantly increases short-term cognitive knowledge about the ACGME competencies among participants and improves trainees' perceptions of the quality of faculty feedback up to 6 months after training.

Introduction

Residency programs are responding to the challenge of developing the best processes for transforming practicing clinicians into skilled teachers in medical education. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) instituted training in 6 general competencies to improve the quality of graduate medical education, with a focus on educational outcomes.1 Teaching the ACGME competencies has further emphasized the importance of and need for developing faculty as effective medical educators. Many institutions have developed formal teaching programs in which a select group of motivated and interested clinicians are enrolled in a course comprising didactics, curriculum design, assessment, and research. These programs have been shown to be useful in developing educational leaders.2–5 A comprehensive approach to faculty development should include instruction on educational scholarship and leadership, organizational skills, teaching methods, and personal improvement.6,7 The time commitment required to create programs to motivate and develop the teaching skills of voluntary faculty (members of the medical staff involved with the training of residents and medical students who are not employed by the department) makes this more challenging. Many institutions are concerned about the recruitment and retention of nonsalaried physicians who volunteer their time to teach.8–10

The Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Cedars Sinai Medical Center embarked on a project to improve the teaching abilities of its faculty and residents. Major goals included improving the consistency and teaching ability of the voluntary faculty and creating a supportive environment for teaching. Faculty education would increase awareness of the residency program's goals and provide instruction on effective teaching tools, with the objective of linking educational outcomes with program improvement. A major challenge is that voluntary faculty members do not receive financial support from the institution and usually have busy clinical services that preclude extensive time commitments for “educational advancement.”

It is essential to prepare the residents as teachers. Residents are the major teachers of medical students and junior residents.11 Training residents would increase their awareness of faculty and program expectations, which would improve their ability to be effective learners,12 increase faculty and resident alignment, and reduce the likelihood of conflict and confusion.

This study reports on the development and implementation of a didactic and Internet-based educational program to teach voluntary faculty and residents how to promote the ACGME competencies and Residency Review Committee (RRC) guidelines and how to be effective teachers to improve the quality of medical education. We hypothesized that a structured faculty development program would increase cognitive knowledge about the ACGME competencies and that residents would receive useful and timely feedback.

Methods

The department includes 20 residents in an ACGME-accredited training program in obstetrics and gynecology and 21 full-time faculty physicians, all of whom are subspecialists. Annually, about 36 third-year medical students from the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA complete their core rotation in obstetrics and gynecology at the department. There are approximately 60 voluntary faculty physicians, about 90% of whom are generalists. The generalists teach and supervise residents and medical students on general obstetrics and gynecology rotations.

This study was exempted from institutional review board approval. We used the 6-step approach by Kern et al13 that has been demonstrated as an effective method of curriculum development.

Step 1: Problem Identification and General Needs Assessment

The initiative sought to improve teaching skills and awareness of the ACGME competencies. Our first step was to select voluntary faculty who were interested in teaching. After extensive consultation and dialogue, the department created teaching and nonteaching faculty categories. Teaching faculty comprised those who allowed residents to do 50% of surgical cases on the gynecology service or who agreed to involve residents in at least 50% of their vaginal deliveries on the obstetrics service. The minimum number of cases to remain on the teaching faculty was 10 gynecologic surgical cases or 10 vaginal deliveries with involvement of residents in the course of 1 year. Faculty could be teaching on 1 or both services. Residents participated in the management of all patients of the teaching faculty. Teaching faculty were evaluated annually to ensure that the minimum number of cases with resident participation was met, and they were required to be involved in educational programs.

Step 2: Needs Assessment of Targeted Learners

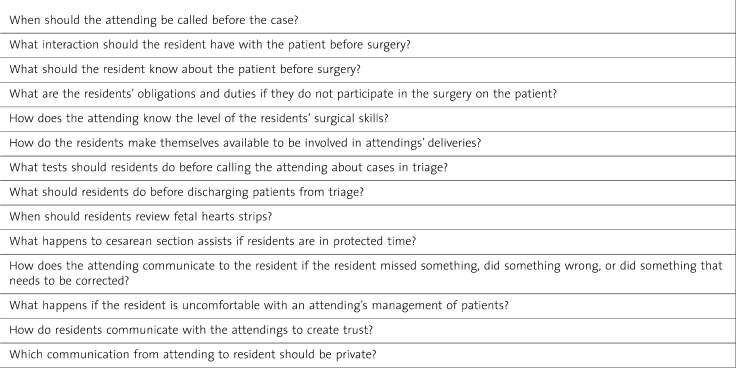

Needs assessment of targeted learners was accomplished by a faculty and resident task force that included residents and full-time and voluntary faculty. Initial meetings identified a lack of shared clear expectations between teachers and learners that resulted in communication based on unknown and nonnegotiated goals, with consequent confusion, conflict, and frustration. To foster a positive educational climate, a relationship was needed between faculty and residents that emphasizes communication and cooperation, as well as an environment of trust in which teachers and learners understand the goals of the learning experience. During subsequent meetings, an organizational coach acted as the facilitator and the program director as the moderator. A list of questions regarding faculty and resident expectations on all clinical services was developed, with all parties contributing and deciding by consensus. Sample questions are given in table 1. Two areas were identified for further education, namely, giving effective feedback and understanding “regulatory” aspects of the program requirements such as those related to resident duty hours.

Table 1.

Sample Questions Addressed by the Faculty and Resident Task Force

Step 3: Goals and Objectives

Once the needs of the target population of learners were identified, the consensus effort developed goals and objectives for the curriculum. They included the following: (1) to improve faculty knowledge of the ACGME competencies, (2) to improve resident feedback, and (3) to improve faculty knowledge of the RRC guidelines and regulations for the residency program.

Step 4: Educational Strategies

A course to teach faculty and residents was developed by the program director with input from the faculty. Three PowerPoint (Microsoft, Seattle, Washington) slide modules on assessing and teaching the ACGME competencies and on selected RRC program requirements were created and installed on a website. Faculty and residents participated in beta testing the course and gave feedback. In addition, the course was presented to a group of administrators and faculty who reviewed the content and format. Feedback resulted in several refinements to the course. The website also included video clips on feedback and teaching in the operating room that were developed specifically for this course. A pretest and posttest were developed and included with each module.

Step 5: Implementation

Initially, the course was piloted as a didactic session mainly through evening dinner seminars to a group of 15 to 20 faculty members and during resident didactic sessions. Faculty and residents were then asked to take the online course.

Step 6: Evaluation and Feedback

Improvement in cognitive knowledge was assessed by the pretest and posttest. Residents' perception of feedback was assessed through a survey that they completed at the initiation of the course and 6 months later. Assessment also included a satisfaction survey completed by faculty during a grand rounds session held after the intervention. An online postprogram satisfaction survey was completed at the conclusion of the course.

Problem identification started in February 2005, and the faculty and resident task force met from October to December 2007. The teaching modules were developed during the same period, and the online program was implemented in January 2008. The residents' survey on feedback was conducted in January and August 2008 using SurveyMonkey.com. The sample sizes for faculty and residents vary because assessments were completed at different times.

Results

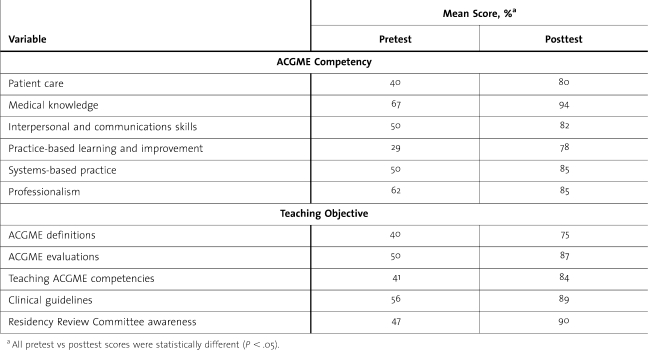

This study analyzes data for 38 voluntary faculty physicians and 11 residents who completed the course. The results of faculty and residents were similar and are presented together. table 2 summarizes the significant improvement in cognitive knowledge for all ACGME competencies and teaching objectives. The most marked improvement was in the area of practice-based learning and improvement, with a mean score of 29% on the pretest compared with 78% on the posttest.

Table 2.

Pretest and Posttest Scores Among 49 Voluntary Faculty and Residents by Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Competencies and Teaching Objectives (N = 49)

Twenty-five faculty physicians completed the program assessment during a grand rounds session after the intervention. Using a Likert-type scale with scores ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), the overall mean score for the program was 4.4, and 100% of the participants thought that the program had improved their ability to teach. Specific written comments on how the information changed the participants' practice included “giving feedback,” using the RIME (reporter, investigator, manager, educator) technique, “remembering to ask residents to perform self-assessments before giving feedback,” and “giving learner information about what they can improve on.”

An online survey completed by 9 faculty and residents showed that most agreed that the course improved their knowledge on all 3 modules and that they perceived the course had improved their teaching. One concern expressed was that the course was too long. The residents' regular semiannual evaluations of their training were an additional assessment of the effect of the course on residents' perceptions of the program. Two questions assessed faculty teaching, and residents' assessment scores after the faculty development program were compared with scores from the prior academic year. For the question “Does the teaching staff properly educate the resident?”, the mean score was 0.94 compared with 0.88 before initiation of the teaching program. For the question “Does the teaching staff provide timely, clear, and pertinent feedback?”, the mean score was 0.92 compared with 0.85 before initiation of the teaching program.

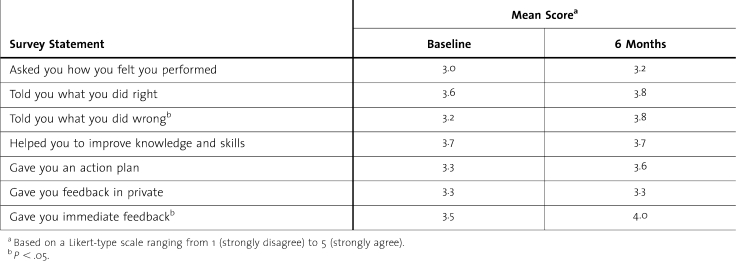

table 3 summarizes resident survey data on their perception of faculty feedback at baseline and 6 months after implementation of the teaching program. Statistically significantly improvement was found in the aspects of immediacy of feedback and of instruction about what the resident did wrong. Faculty provision of an action plan demonstrated a trend toward improvement (P = .06). After the intervention, residents perceived no change in privacy of feedback or assistance to improve their knowledge and skills.

Table 3.

Perception of Faculty Feedback at Initiation and 6 Months After the Intervention Among 13 Residents

Discussion

In the faculty development program outlined herein, organizational improvement was accomplished by creating an intervention targeting voluntary teaching faculty and residents. The recruitment and retention of nonsalaried physicians who volunteer their time to teach represents a challenging undertaking. In our study, we asked physicians to self-select for inclusion as teaching faculty, as these individuals are likely to be the most motivated to teach. Notably, our teaching faculty benefit from departmental recognition and from coverage of their patients by residents 24 hours a day.

A tenet of learning is that expectations and objectives have to be set in advance.12 Creation of the faculty and resident task force allowed faculty and residents to set expectations. This experience not only was invaluable in creating clear expectations but also served to improve the interpersonal communication and relationships between faculty and residents. Dunstone14 published qualitative data indicating that educational workshops for voluntary faculty in psychiatry encouraged collaboration and enhanced teaching. The present study builds on previous work by including quantitative data and 6 months of follow-up data.

Instructional development was accomplished by the development of a curriculum, the provision of pilot group seminars, and the Internet-based online course for faculty and residents. Scores on posttests vs pretests from the Internet-based online program demonstrated acquisition of knowledge. The importance of feedback is well established as being crucial to learning. For this reason, our instructional material focused on feedback. More than half of the module on teaching reviewed the importance of proper feedback relative to the efficacy of teaching, as well as techniques on accomplishing this objective.

The survey data suggest that the program was beneficial and improved the participants' ability to teach. The semiannual survey found improvement in residents' perceptions of the amount of feedback they receive. Compared with baseline, the survey after the intervention showed statistically significant improvement in corrective and immediate feedback, with a trend toward significance for receipt of an action plan. These observations highlight aspects that may need targeted educational interventions. Our results suggest that the faculty educational development program contributed to improving the educational environment of the residency program.

Limitations of this study include its small sample size and the use of a single academic department as the test site; therefore, the results may not be generalizable. In addition, a subset of the faculty and residents took the online course, and there may be some self-selection bias in our results. Also, it is possible that factors not studied may have contributed to improvement in the residents' perceptions of their experience and of faculty feedback. Confounding factors that could be relevant include variability in formal knowledge, continuing medical education activities, expertise, experience, and motivation and desire of the voluntary faculty. Finally, we did not assess long-term knowledge retention or feedback perception beyond 6 months.

In conclusion, it is feasible to develop a structured “teaching the teachers” program that can facilitate a positive and nurturing educational climate. This was accomplished by creating a teaching faculty and by implementing a didactic online educational curriculum, which included information on the ACGME competencies, the RRC guidelines, and methods for improving efficacy as teachers. The program is ongoing, and faculty and residents at the beginning of each academic year who have not taken the course are requested to complete it. To maintain ongoing faculty development, it is proposed that faculty and residents will be asked to view educational videos or presentations at intervals of 1 to 2 years. Our positive results of an innovative approach to teaching a large number of voluntary faculty may encourage other programs to explore the development of systematic and structured teaching programs, with the goal of improving the quality of medical education at their institutions.

Footnotes

Dotun Ogunyemi, MD, Ewina Fung, MD, Carolyn Alexander, MD, David Finke, MD, Jonathan Solnik, MD, and Ricardo Azziz, MD, MBA, are with the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles.

This 2008–2009 project was supported by the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics/Solvay Pharmaceuticals Educational Scholars Development Program.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/home/home.asp. Accessed January 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Steinert Y., McLeod P. J. From novice to informed educator: the Teaching Scholars Program for Educators in the Health Sciences. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):969–974. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000242593.29279.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller J. H., Irby D. M. Developing educational leaders: the Teaching Scholars Program at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):959–964. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000242588.35354.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkerson L., Uijtdehaage S., Relan A. Increasing the pool of educational leaders for UCLA. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):954–958. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000242477.01887.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheilds H. M., Guss D., Somers S. C. A faculty development program to train tutors to be discussion leaders rather than facilitators. Acad Med. 2007;82(5):486–492. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31803eac9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sachdeva A. K. Faculty development and support needed to integrate the learning of prevention in the curricula of medical schools. Acad Med. 75(7)(suppl):S35–S42. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200007001-00006. 200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkerson L., Irby D. M. Strategies for improving teaching practices: a comprehensive approach to faculty development. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):387–396. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar A., Kallen D. J., Mathew T. Volunteer faculty: what rewards or incentives do they prefer? Teach Learn Med. 2002;14(2):119–123. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1402_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vath B. E., Schneeweiss R., Scott C. S. Volunteer physician faculty and the changing face of medicine. West J Med. 2001;174(4):242–246. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.174.4.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irby D. M. Where have all the preceptors gone? erosion of the volunteer clinical faculty [commentary] West J Med. 2001;174(4):246. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.174.4.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann K. V., Sutton E., Frank B. Twelve tips for preparing residents as teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29(4):301–306. doi: 10.1080/01421590701477431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heidenreich C., Lye P., Simpson D., Lourich M. The search for effective and efficient ambulatory teaching methods through the literature. Pediatrics. 105(1, pt 3):231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kern D. E., Thomas P. A., Howard D. M., Bass E. B. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunstone D. A pilot study for integrating volunteers with core psychiatry faculty. Acad Psychiatry. 2005;29(3):262–266. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.29.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]