Abstract

Background

Residents are evaluated using Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies. An Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) is a potential evaluation tool to measure these competencies and provide outcome data.

Objective

Create an OSCE to evaluate and demonstrate improvement in intern core competencies of patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice before and after internship.

Methods

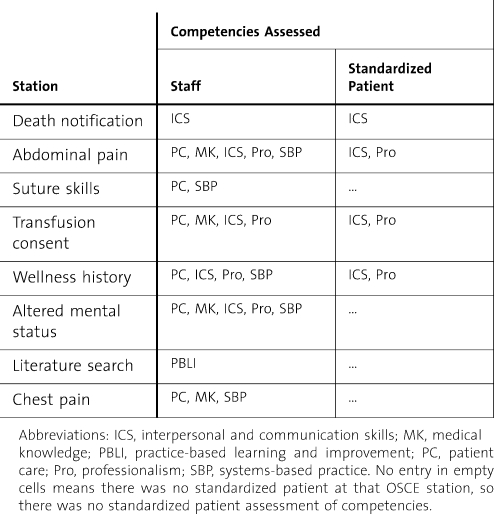

From 2006 to 2008, 106 interns from 10 medical specialties were evaluated with a preinternship and postinternship OSCE at Madigan Army Medical Center. The OSCE included eight 12-minute stations that collectively evaluated the 6 ACGME core competencies using human patient simulators, standardized patients, and clinical scenarios. Interns were scored using objective and subjective criteria, with a maximum score of 100 for each competency. Stations included death notification, abdominal pain, transfusion consent, suture skills, wellness history, chest pain, altered mental status, and computer literature search. These stations were chosen by specialty program directors, created with input from board-certified specialists, and were peer reviewed.

Results

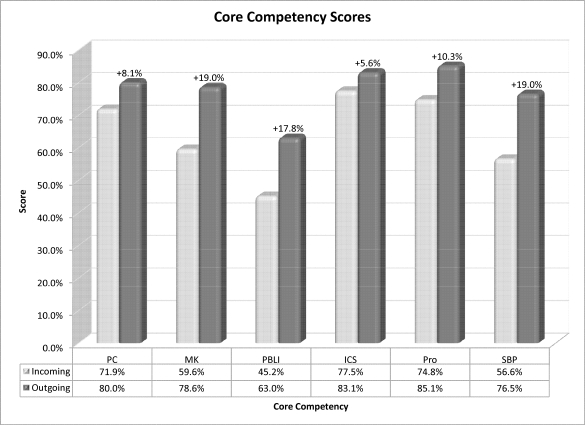

All OSCE testing on the 106 interns (ages 25 to 44 [average, 28.6]; 70 [66%] men; 65 [58%] allopathic medical school graduates) resulted in statistically significant improvement in all ACGME core competencies: patient care (71.9% to 80.0%, P < .001), medical knowledge (59.6% to 78.6%, P < .001), practice-based learning and improvement (45.2% to 63.0%, P < .001), interpersonal and communication skills (77.5% to 83.1%, P < .001), professionalism (74.8% to 85.1%, P < .001), and systems-based practice (56.6% to 76.5%, P < .001).

Conclusion

An OSCE during internship can evaluate incoming baseline ACGME core competencies and test for interval improvement. The OSCE is a valuable assessment tool to provide outcome measures on resident competency performance and evaluate program effectiveness.

Introduction

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) began a long-term initiative known as the Outcome Project in 1996 by first identifying the 6 general core competencies of patient care (PC), medical knowledge (MK), professionalism (Pro), systems-based practice (SBP), practice-based learning and improvement (PBLI), and interpersonal and communication skills (ICS). As part of the ACGME Outcome Project, programs will be required to use more objective methods to assess resident attainment of competency-based objectives. These objective evaluation tools should then be used to improve resident and program performance.1 The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) with the use of standardized patients and simulation is rated as the most desirable or next best method in assessing most required skills within the 6 ACGME core competencies.2

The OSCE was first conceptualized in 1975 when students were given patient-oriented tasks to complete in a controlled setting while their clinical competence was assessed.3 Since that time, OSCEs have been used in medical schools to assess medical student performance of clinical skills.4–6 The clinical skills examination that was incorporated into the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 2 in 2004 is, in essence, a national OSCE for all US allopathic medical students.7 The OSCE is traditionally administered using multiple simulated clinical encounters lasting 10 to 15 minutes.8 An OSCE most often uses standardized patients to portray a particular disease or condition; however, other simulation tools may be used, including data interpretation, technical skills stations, and clinical scenarios with human patient simulators.9 Examinees may also perform various tasks such as test interpretation, history taking, physical examination, patient education, or order writing.10,11

There are growing, but limited, OSCE data in the area of graduate medical education, especially as it relates to the core competencies. Some studies have tested the baseline knowledge and skill levels of incoming residents, but did not repeat the OSCE at the end of the year to look for interval improvement.12,13 Several studies have demonstrated the ability of sequential OSCEs to show improvement after specific educational interventions such as “breaking bad news” training,14 “integration of health education principles” training,15 substance abuse training,16 osteoporosis17 and breastfeeding workshops,18 a critical care medicine clinical elective,19 and the Advanced Trauma Life Support course.20 All of these educational interventions, however, have been short-duration courses focusing on specific educational topics. The ability of the OSCE to show sequential improvement and to detect both positive and negative interval change over time has been demonstrated.21,22 Data showing how an OSCE can be used for competency-based improvement among postgraduate year-1 residents have not been established.

The purpose of this study was to create and administer an OSCE to evaluate interns on the 6 ACGME core competencies before and after internship to provide educational outcomes data that may be used to improve individual resident and overall program performance.

Methods

A total of 106 interns from 10 medical specialties underwent a preinternship and postinternship OSCE between June 2006 and May 2008. The preinternship OSCE was conducted in June during intern orientation and prior to training. The postinternship OSCE was conducted 10 months later at the end of the academic year. Interns were entering ACGME-accredited programs in emergency medicine, internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, neurology, general surgery, orthopedics, otolaryngology, and transitional year. Interns completed the standard rotations for their specialty training program during the intern year.

The OSCE Stations

The OSCE consisted of eight 12-minute stations using standardized patient scenarios, high-fidelity human patient simulators, and a computer-based simulation. The scenarios collectively evaluated the 6 ACGME core competencies (table 1). The station topics were selected by a multidisciplinary panel of board-certified physician educators at Madigan Army Medical Center to evaluate medical skill areas that would be expected of any medical school graduate. Station scenarios and evaluation forms were created by a board-certified physician and reviewed for accuracy and content by 4 additional physician educators. The stations were standardized to ensure that all interns received the same information without hints, reminders, or recommendations from the evaluator or the standardized patient. The timing of each station was strictly enforced by the OSCE coordinator. Interns did not receive feedback on their performance after the initial OSCE, nor were they or their program directors notified of their scores. Interns were not informed that the end-of-year OSCE would consist of the same stations.

Table 1.

Stations and Assessed Competencies

Death Notification Station

This station used a standardized family member scenario, and the ICS competency was evaluated by a staff internist and a certified social worker. The intern was directed to a private room to notify a family member that her mother had died from a large-volume intracranial hemorrhage.

Abdominal Pain Station

This station used a standardized patient, and the PC, MK, ICS, Pro, and SBP competencies were evaluated by a staff gynecologist. The intern assessed, examined, and provided an initial management plan for a 17-year-old adolescent girl with intense right lower quadrant abdominal pain.

Suture Skills Station

This station used tissue simulation with pig's feet, and the PC and SBP competencies were evaluated by a staff surgeon. The intern managed a deep thigh laceration of a 19-year-old man. Procedure preparation, technique, instructions, and precautions were evaluated.

Transfusion Consent Station

This station used a standardized patient, and the PC, MK, ICS, and Pro competencies were evaluated by a staff pathologist who is the director of the hospital blood bank. The intern obtained consent from a patient for 2 units of packed red blood cells for symptomatic anemia, and discussed the risks and complications of a blood transfusion on patient questioning.

Wellness Visit History Station

This station used a standardized patient, and the PC, ICS, Pro, and SBP competencies were evaluated by a staff family physician. The intern obtained a wellness history on a 65-year-old woman, and ordered the appropriate laboratory tests, radiographs, and consults for a routine preventive visit.

Altered Mental Status Station

This station used a human patient simulator, and the PC, MK, ICS, Pro, and SBP competencies were evaluated by a staff neurologist. The intern evaluated an agitated and confused patient on the ward, listed a differential diagnosis, and recommended laboratory tests, other tests, studies, and a management plan.

Literature Search Station

This station used a web-based computer search, and the PBLI competency was evaluated by a staff pediatrician. The intern searched for 2 references to answer a clinical question, and compared these articles for the evaluator. There were different clinical questions for the preinternship and postinternship OSCE: antibiotic use in otitis media and cranberry juice for urinary tract prophylaxis.

Chest Pain Station

This station used a human patient simulator, and evaluated the PC, MK, and SBP competencies. The intern managed chest pain, ventricular fibrillation, and hyperkalemia in a 67-year-old man who presented to the emergency department.

Evaluation Forms and Data Interpretation

The physician evaluator at each station evaluated resident competency performance on computerized evaluation forms using both objective and subjective criteria. Standardized patients evaluated resident performance in the ICS and Pro competencies (table 1). The objective measurements were graded in a binomial (yes/no) format, and were predominately used for PC and MK areas. Subjective measurements were graded using a 5-point Likert scale, and were predominately used for Pro and ICS competencies. Each of the 8 stations contributed to the overall ACGME core competency scores and provided for the ability to weight each of the ACGME core competencies equally. The individual ACGME core competency scores were reported as a percentage of the maximum score attained by any intern on the outgoing OSCE for the 2-year study period. Individual station data performance was also calculated, and reflects either the PC or MK component of the stations evaluating more than 1 competency, or the single competency assessed at that station.

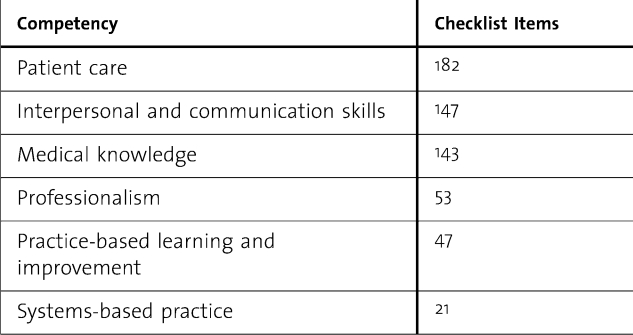

Data were collected on standardized InfoPath forms (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) and consolidated into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft). It was imported into an Access database (Microsoft) for data manipulation, and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 14 (SPSS Science Inc, Chicago, IL). Preinternship and postinternship OSCE scores were compared for each individual intern, by residency department, and overall for each core competency. Before and after training aggregate scores were also calculated. Significance on the ACGME competency scores was determined using parametric paired sample testing based on individual resident scores. Reliability of this OSCE as an assessment tool was strengthened by using the same evaluators for the preinternship and postinternship OSCE for each year group, providing standardized instructions and education to evaluators on how to use evaluation forms, and using multiple checklist items to evaluate each core competency (table 2).

Table 2.

Checklist Items for Each Competency

This study received institutional review board approval from Madigan Army Medical Center, Fort Lewis, Washington. There was no outside funding for this study.

Results

There were 112 interns from 10 residency programs who participated in the incoming OSCE from 2006 to 2008. There were 6 interns who participated in the incoming OSCE, but were not able to participate in the outgoing OSCE because of scheduling conflicts such as away clinical rotations or maternity leave. The data analysis for this study was based on the 106 interns who participated in both the incoming and outgoing OSCE. The participant ages ranged from 25 to 44 years, with an average age of 28.6. There were more men than women, 70 (66%) versus 42 (34%). All were US medical school graduates with more allopathic than osteopathic interns, 65 (58%) versus 47 (42%). The represented programs included transitional year (n = 19), emergency medicine (n = 16), internal medicine (n = 17), family medicine (n = 12), pediatrics (n = 12), obstetrics and gynecology (n = 8), neurology (n = 5), general surgery (n = 8), orthopedics (n = 5), and otolaryngology (n = 4).

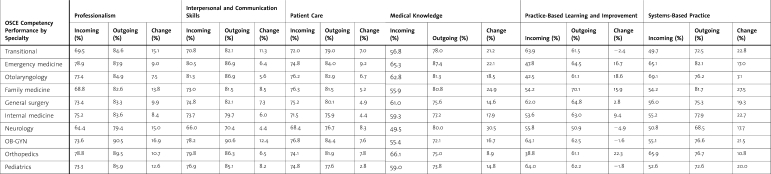

There was statistically significant improvement in all 6 ACGME core competency scores among the 106 interns (figure 1): PC (71.9% to 80.0%, P < .001), MK (59.6% to 78.6%, P < .001), PBLI (45.2% to 63.0%, P < .001), ICS (77.5% to 83.1%, P < .001), Pro (74.8% to 85.1%, P < .001), and SBP (56.6% to 76.5%, P < .001). Scores and improvement by specialty program are listed in table 3.

Figure 1.

Core Competency Scores

Table 3.

Competency-Based Scores by Specialty

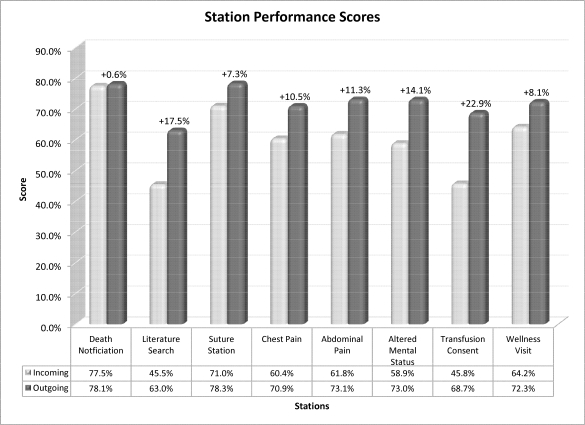

There was also statistically significant improvement in station performance for 7 of the 8 stations (figure 2): death notification (77.5% to 78.1%, P = .66), abdominal pain (61.8% to 73.1%, P < .001), suture station (71.0% to 78.3%, P < .001), transfusion consent (45.8% to 68.7%, P < .001), wellness visit (64.2% to 72.3%, P < .001), altered mental status (58.9% to 73.0%, P < .001), literature search (45.5% to 63.0%, P < .001), and chest pain (60.4% to 70.9%, P < .001).

Figure 2.

Station Performance Scores

Discussion

The OSCE and Program Effectiveness

A competency-based OSCE can be a valuable tool to assess program performance and provide educational outcome data to residency programs. This research significantly contributes to the current OSCE literature by showing statistically significant competency improvement of intern performance after repeat testing at the end of the academic year. Competency performance by specialty, however, did not consistently improve after the intern year (table 3). Programs not showing significant improvement in some competency areas can use these data to implement changes in their program curriculum. A low resident mean score in PBLI, for example, may prompt a program to implement tools to teach residents how to locate evidence-based medicine articles and critically evaluate those articles. Resident improvement on a subsequent OSCE can then provide evidence that the program made a meaningful difference in teaching that competency. Using the OSCE as an outcome assessment tool allows programs to meet the intent of the ACGME outcome project, and be better prepared for future accreditation site visits that focus on actual program accomplishments.

The OSCE and Individual Resident Performance

Our next step is to determine if the OSCE can be a reliable summative assessment tool for individual residents achieving program benchmarks. The OSCE does provide meaningful formative data to compare residents to their local peer groups, which can assist program directors in modifying curriculum to meet individual resident needs. Using the OSCE as a high-stakes final assessment will require more data to determine validity and reliability.

The OSCE Challenges

When creating an OSCE, one size does not fit all. At the intern level, in our smaller institution, it was useful to create a single OSCE that worked for all specialty programs within our facility. This allowed sharing of resources and volunteers to make the process more efficient. For programs wishing to create an OSCE to measure residency-specific performance, the OSCE would need to be tailored to fit the needs of that program. For example, the OSCE described in this study would be useful for graduates in family medicine or emergency medicine programs. Modifications would be needed before testing graduates of pediatric and surgical specialty programs.

Using the same OSCE stations for the before and after examinations was one potential bias in this study.23 This “practice effect” bias was minimized by not providing interns with feedback after their initial OSCE, and not informing interns that the second OSCE would have the same stations. This bias was also decreased by the time between testing. Even if a small benefit was gained by retaking the same test, residents more importantly showed competency improvement at the end of the year as a result of clinical practice and familiarity with these commonly encountered scenarios. A second potential bias in this study was that evaluators were not blinded to the intern's specialty. Evaluators knew which interns were from primary care and surgical specialties.

In summary, the creation and use of a competency-based OSCE can evaluate intern performance before and after internship to provide educational outcomes data that may be used to improve individual resident and overall program performance. Tracking of OSCE scores over time can provide an objective measurement of resident and program improvement.

Footnotes

MAJ Matthew W. Short, MD, FAAFP; Director, Transitional Year Program, Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, WA; Adjunct Assistant Professor of Family Medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Bethesda, MD; Clinical Instructor of Family Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle,WA; Jennifer E. Jorgensen, MD, FACP; Gastroenterology Fellow, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, MI; LTC John A. Edwards, MD, MPH, FAAFP; Director, Intern Training, Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, WA; Clinical Instructor of Family Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA; Robert B. Blankenship, MD, FACEP; Medical Director, St. Vincent Medical Center Northeast, Fishers, IN; COL Bernard J. Roth, MD, FACP, FACCP; Director, Graduate Medical Education, Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, WA; Associate Professor of Medicine, Uniformed Services University of Health Science, Bethesda, MD; Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of Washington, Division of Pulmonary/Critical Care Medicine, Seattle, WA.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the US Government.

Previous presentations: poster presentation, Central Simulation Committee Annual Meeting; May 12–15, 2009; San Antonio, Texas; poster presentation, National Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physicians Annual Meeting; April 3–8, 2009; Orlando, Florida (received the staff category Clinical Investigations Committee (CIC) chair award for previously presented research); poster presentation, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education annual educational conference; March 5–8, 2009; Grapevine, Texas; oral presentation, 2008 Joint Service Graduate Medical Education Selection Board; December 4, 2008; Washington, DC; poster presentation, American Academy of Family Physicians Scientific Assembly; September 17–21, 2008; San Diego, California; poster presentation, Association for Hospital Medical Education Spring Educational Institute; May 7, 2008; San Diego, California (received first place for Viewer's Choice Award for poster presentations); oral presentation, Western Regional Medical Command Madigan Research Day; April 25, 2008; Fort Lewis, Washington; and poster presentation, Annual State of the Military Health System Conference; January 29, 2008; Washington, DC.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Outcome project. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Outcome/. Accessed April 16, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and American Board of Medical Specialties Joint Initiative. Toolbox of assessment methods. Version 1.0, Summer 2000. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Outcome/assess/Toolbox.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2009.

- 3.Harden R., Stevenson M., Downie W. W., Wilson G. M. Clinical competence in using objective structured examination. Br Med J. 1975;1:447–451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5955.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casey P. M., Goepfert A. R., Espey E. L. To the point: reviews in medical education–the Objective Structured Clinical Examination. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon S. R., Bui A., Day S., Berti D., Volkan K. The relationship between second-year medical students' OSCE scores and USMLE Step 2 scores. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(6):901–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tervo R. C., Dimitrievich E., Trujillo A. L., Whittle K., Redinius P., Wellman L. The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in the clinical clerkship: an overview. S D J Med. 1997;50(5):153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Medical Licensing Examination. Step 2 clinical skills. Content description and general information. Available at: http://download.usmle.org/2009/2009CSinformationmanual.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2009.

- 8.Turner J. L., Dankoski M. E. Objective structured clinical exams: a critical review. Fam Med. 2008;40(8):574–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J. D., Erickson J. C., Short M. W., Roth B. J. Education research: evaluating acute altered mental status: are incoming interns prepared? Neurology. 2008;71(18):e50–e53. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327880.58055.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howley L. Performance assessment in medical education: where we've been and where we're going. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):285–303. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Vleuten C. P. M., Swanson D. B. Assessment of clinical skills with standardized patients: state of the art. Teach Learn Med. 1990;2(2):58–76. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.842916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lypson M. L., Frohna J. G., Gruppen L. D., Woolliscroft J. O. Assessing residents' competencies at baseline: identifying the gaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(6):564–570. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner D. P., Hoppe R. B., Lee C. P. The patient safety OSCE for PGY-1 residents: a centralized response to the challenge of culture change. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(1):8–14. doi: 10.1080/10401330802573837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amiel G. E., Ungar L., Alperin M., Baharier Z., Cohen R., Reis S. Ability of primary care physicians to break bad news: a performance based assessment of an educational intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hafler J. P., Connors K. M., Volkan K., Bernstein H. H. Developing and evaluating a residents' curriculum. Med Teach. 2005;27:276–282. doi: 10.1080/01421590400029517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews J., Kadish W., Barrett S. V., Mazor K., Field D., Jonassen J. The impact of a brief interclerkship about substance abuse on medical students' skills. Acad Med. 2002;77:410–426. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis P., Kvern B., Donon N., Andrews E., Nixon O. Evaluation of a problem-based learning workshop using pre- and post-test objective structured clinical examinations and standardized patients. J Cont Educ Health Prof. 2000;20:164–170. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haughwout J. C., Eglash A. R., Plane M. B., Mundt M. P., Fleming M. F. Improving residents' breastfeeding assessment skills: a problem-based workshop. Fam Pract. 2000;17:541–546. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.6.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers P. L., Jacob H., Thomas E. A., Harwell M., Willenkin R. L., Pinskey M. R. Medical students can learn the basic application, analytic, evaluative, and psychomotor skills of critical care medicine. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:550–554. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200002000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali J., Cohen R., Adam R. Teaching effectiveness of the advanced trauma life support program as demonstrated by an objective structured clinical examination for practicing physicians. World J Surg. 1996;20:1121–1125. doi: 10.1007/s002689900171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan C. S., Wun Y. T., Cheung A. Communication skill of general practitioners: any room for improvement? How much can it be improved? Med Educ. 2003;37:514–526. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prislin M. D., Giglio M., Lewis E. M., Ahearn S., Radecki S. Assessing the acquisition of core clinical skills through the use of serial standardized patient assessments. Acad Med. 2000;75:480–483. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200005000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss E., Sherman E., Spreen O. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 11. [Google Scholar]