Abstract

Context

Chief residents play a crucial role in internal medicine residency programs in administration, academics, team building, and coordination between residents and faculty. The work-life and demographic characteristics of chief residents has not been documented.

Objective

To delineate the demographics and day-to-day activities of chief residents.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Survey Committee of the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine (APDIM) developed a Web-based questionnaire. A link was sent in November 2006 by e-mail to 381 member programs (98%). Data collection ended in April 2007.

Measurements

Data collected include the number of chief residents per residency, the ratio of chief residents per resident, demographics, and information on salary/benefits, training and mentoring, and work life.

Results

The response rate was 62% (N = 236). There was a mean of 2.5 chief residents per program, and on average there was 1 chief resident for 17.3 residents. Of the chief residents, 40% were women, 38% international medical graduates, and 11% minorities. Community-based programs had a higher percentage of postgraduate year 3 (PGY-3)–level chief residents compared to university-based programs (22% versus 8%; P = .02). Mean annual salary was $60 000, and the added value of benefits was $21 000. Chief residents frequently supplement their salaries through moonlighting. The majority of formal training occurs by attending APDIM meetings. Forty-one percent of programs assign academic rank to chief residents.

Conclusion

Most programs have at least 2 chief residents and expect them to perform administrative functions, such as organizing conferences. Most programs evaluate chief residents regularly in administration, teaching, and clinical skills.

Background

The chief resident plays an important role in internal medicine residencies, being positioned at the nexus between faculty and residents. The position is considered one of honor and prestige and provides a mark of distinction when applying for fellowship positions.1,2 The job description may differ from one program to the next, ranging from a junior faculty position with high clinical demands to a more administrative office with expectations to lead recruiting efforts. It traditionally has a heavy didactic responsibility.

Administrative, management, and personnel skills are crucial for a successful chief resident.3 Chief residents act as role models,4 build teamwork,5 identify problem residents, and give constructive feedback.6 Chief residents act as a link and advocate for residents to the program administration—comparable to a “middle manager.”7,8 They also organize grand rounds, facilitate morning reports, and provide bedside teaching while attending on hospital wards.9 To date, no studies have addressed the demographics and day-to-day work life of chief residents. Our study attempted to provide these data using a nationwide survey of internal medicine program directors.

Methods

The Survey Committee of the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine (APDIM) is charged with developing questionnaires to track the baseline characteristics of the internal medicine residencies in the United States and to address current issues facing residencies and residency directors. The Survey Committee designed the questionnaire used in this study to include a section with questions specific to the chief residents' demographics, selection, training, job expectations, salary, mentoring, and job evaluation. The survey was pilot tested with small-group program directors to ensure face validity, and questions were assessed and modified prior to full distribution. In November 2006, we sent an e-mail notification with a program-specific hyperlink to the questionnaire to 381 of 388 (98%) APDIM member programs, representing US categorical internal medicine residency programs. Nonresponders were contacted by e-mail in December 2006 and January 2007. Data collection ceased in April 2007. Programs were assigned a US region,10 and we obtained the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) 3-year rolling pass rate for each program from the ABIM website.11 Programs identified were then blinded. The study was approved by the Mayo Foundation Internal Review Board.

Data Analysis

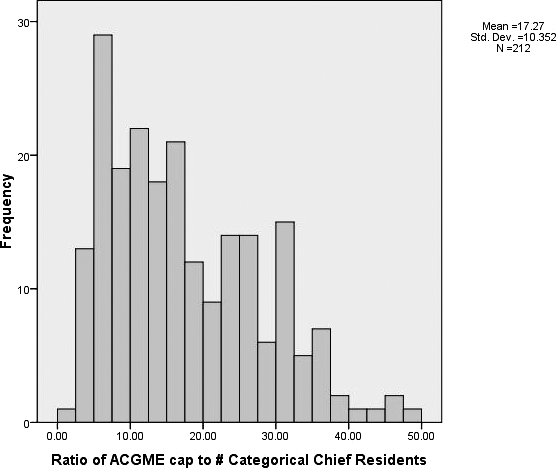

We used SPSS Statistics 17.0.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) for all analyses. Each residency was categorized by setting (university-based, community-based, military, Veterans Administration, multispecialty group), and the number of residents (using the total number of positions approved by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education [ACGME] 12). We combined response categories for variables when we found sparsely selected responses. We examined continuous variables for evidence of skewness, outliers, and nonnormality. One of our main variables of interest, the program's ratio of residents to chief residents, was not a normal distribution (figure), and we used nonparametric equivalency tests for associations with this variable: the Spearman rank correlation to look for correlation with the ABIM pass rate and the Kruskal-Wallis test to compare the averages for categorical variables (region and institution type). The ABIM pass rate was used as a surrogate for program quality as it is one of the strongest predictors of accreditation cycle length.13 For all the analyses we used 2-sided tests.

Figure.

The Ratio of the Total Number of Residents to the Chief Resident in Their Respective Internal Medicine Residency Program (n = 212)

Results

Two hundred and thirty-six program directors (62%) completed the survey in 2007. There were no significant differences in the percentage of respondents versus nonrespondents between the different regions of the United States. Responding residency programs had a significantly higher ABIM pass rate than nonrespondents (93% versus 91%; P = .004).

There was a mean of 2.5 chief residents (SD = 1.4) per residency program (the mode was 2, and 6 programs reported 6 chief residents); on average there was 1 chief resident for every 17.3 residents (SD = 10.4; see the figure). The ratio of chief residents to total residents did not differ between regions of the United States and did not correlate with the programs' ABIM pass rates. We also found no significant difference in the ratio based on the program type (ie, university or community program), job duties of the chief resident (ie, hospital attending, clinic preceptor, clinical duties without learners, allowed to moonlight), their academic rank, or the amount of salary and benefits.

Programs reported that over the past 3 years, 40% of their chief residents have been women (mean = 3.1, SD = 2.1), 38% were international medical graduates (mean = 2.8, SD = 3.2), and 11% were underrepresented minorities (mean = 0.8, SD = 1.3).

Thirty-seven programs (16%) reported using postgraduate year 3 (PGY-3)–level residents to perform duties usually assigned to chief residents, and this was more common in community-based programs than in university-based ones (22% versus 8%; P = .02). Only four programs had chief residents that returned after fellowships or after working for a time in the community. Fifty-one programs (23%) accept chief residents from outside of their own institution.

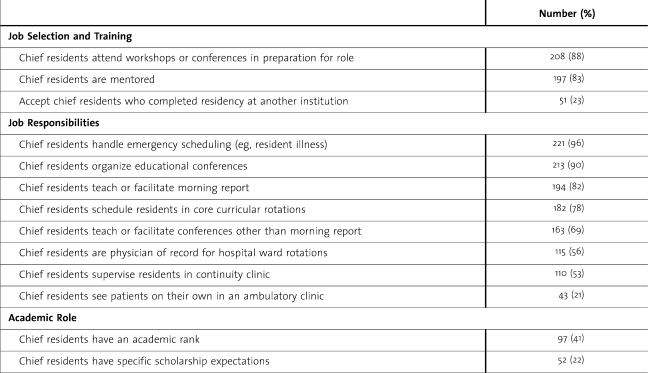

Table 1 describes the selection, training, responsibilities (clinical, academic, and administrative), and academic role of the chief residents. Only 47 programs (21%) have any specific scholarship expectations for this position. Of these, 29 (62%) require grand round presentations, 18 (38%) require research projects, 7 (15%) require national presentations, and 3 (6%) require publications. Two-hundred and eight programs (88%) send their chief residents to job training workshops or conferences in preparation for their chief residency year. Most of the formal training occurs by attending the national APDIM meetings (93%), which host special sessions for chief residents.

Table 1.

The Selection, Training, Responsibilities (Clinical, Academic, and Administrative), and Academic Role of Chief Residents in Internal Medicine Residency Programs in the United States, 2007 (n = 236)

Ninety-seven programs (41%) assign an academic rank to chief residents, most of these being ranked as “Instructor” (N = 84) and a small number as Assistant Professor (N = 3). In 115 programs (56%), chief residents are the physician of record on hospital ward rotations. These chief residents on average attend 10.4 weeks (SD = 8.6) per year. One-hundred and ten programs (53%) have chief residents supervise residents in a continuity clinic setting. These on average spend 1.6 half-day sessions (SD = 1.5) in clinic per week. Seventy-five programs (36%) report having chief residents serve as hospital ward attendings and as continuity clinic preceptors. In 43 programs (21%), chief residents spend on average 1.1 half-day clinic sessions (SD = 0.5) seeing patients on their own without learners.

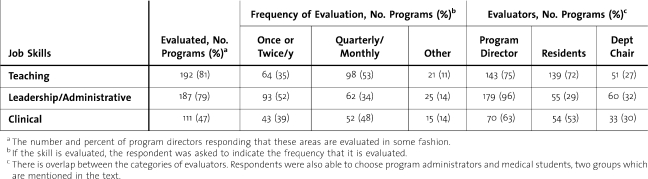

Table 2 demonstrates how often certain chief resident job skills are evaluated and who evaluates them. Teaching skills are evaluated most frequently (53% quarterly or monthly), while clinical skills are evaluated less frequently (only 47% of programs evaluate them). The majority of programs (72%) utilize residents to evaluate chief residents' teaching skills. Other notable responses not seen in Table 2 include program administrators evaluating chief residents' administrative skills in 37 programs (16%) and medical students evaluating chief residents' teaching skills in 88 programs (37%). One hundred and ninety-seven program directors (83%) report that chief residents are mentored during their training.

Table 2.

Internal Medicine Chief Resident Job Evaluation: Skills Evaluated, the Frequency of Evaluation, and the Evaluators, 2007 (n = 236)

The mean annual salary for chief residents was approximately $60 000 (SD = $33, 000) with mean a mean value of annual benefits of $20, 000. One-hundred and ninety-four programs (82%) allow chief residents to moonlight in order to supplement their income. Eighty programs (41%) that permit moonlighting limit the number of moonlighting hours to a mean of 33 hours per month (SD = 22).

Discussion

There are no ACGME internal medicine program requirements, not even with their latest updates effective July 2009, that touch on any aspect of chief residents.14 And yet this role is ubiquitous and necessary to the day-to-day functioning of nearly every residency. If governing organizations are to understand how residencies function optimally, it is important to study this pivotal role.

This survey confirmed that chief residents hold primary roles as educators and managerial heads. They organize and facilitate a variety of conferences and are required to perform both primary and emergency scheduling. The evaluation of chief residents' teaching and administrative skills is performed mainly by the program director and the department chair. However, what is evaluated and who completes the evaluation show a wide amount of variability across programs. Future work might solicit programs for their best practices in evaluative processes to distribute among other residencies.

If one views salary recognition alone as a measure of the position of chief resident, then certainly these individuals may appear to be underappreciated. A chief resident receives a salary less than half of what graduating internists make in the community15 and which usually is supplemented by moonlighting. The survey did not address the sources of funding for chief resident salaries. Since most are board-certified graduates, the residencies likely recoup some of the salaries and benefits of chief residents through the clinical revenue generated by attending on hospital wards and supervising residents in the clinic, but this should be confirmed in a future study. During the course of a chief residency, gaining administrative and teaching skills along with becoming better positioned for fellowships may balance the discussion about salary recognition.

The last study of internal medicine residencies that touched on chief residents was from the “Benchmarks” survey16 published 7 years ago, which documented the relative proportions of chief residents in 1999. At that time there was on average 1 chief resident for every 27 residents, 10 more residents than the current ratio. The figure demonstrates a wide range in this ratio, and we failed to demonstrate a significant association, with many possible variables in our study that might explain the difference. Also, a lower proportion of chief residents are at the PGY-3 level now compared to then—16% in 2007 and 22% in 1999. The reasons for the changes in these proportions and the differences between institutions will require further study, but potential hypotheses include the increasing administrative complexity of keeping up with accreditation regulations17 and a greater pool of potential chief residents who wish to use the job as a springboard toward subspecialty fellowships.18 Additional reasons may include the need for additional board-eligible or board-certified chief residents to undertake clinical and teaching roles.

There are some limitations of this study. First, these results are based on self-report by the program directors, and we may have had different results had the chief residents been surveyed directly on items related to daily work life. This also limited the types of questions that could be asked, and some important and interesting information on the chief resident experience could not be addressed. However, we believe that the program directors are the primary supervisors for these individuals and should know detailed information about most of their job expectations. Future surveys of chief residents are needed to further delineate their experiences and to compare the perceptions of program directors with those of the actual chief residents (eg, on the role of the program director in mentoring the chief resident and number of hours moonlighting).

Secondly, the response rate, while sufficient, was not as high as the Committee had hoped. We did, however, attempt to compare respondents versus nonrespondents on variables that were readily available (region and ABIM pass rate) to demonstrate representativeness of the data set. While there were no significant differences in regions, the ABIM pass rate of respondents was a bit higher than nonrespondents—perhaps an indicator that lower-performing programs lack the resources that would allow the program director time to complete such a survey; however, the survey was not designed to determine such a causal relationship, and the board scores may be a confounder in the interpretation of respondents versus nonrespondents.

Overall, the results update our benchmarks on the mean numbers and proportions of chief residents in the United States and add to our understanding of their daily work activities. The average chief resident might be expected to schedule the residents' rotations, organize their teaching conferences, round 10 weeks per year on hospital wards, precept in clinic 1 day per week, conduct their own clinic 1 half-day per week, and moonlight an extra 8 hours per week. While challenging, we believe the chief resident role is individually rewarding as well as vital to the education of internal medicine residents.

Footnotes

Dushyant Singh, MD, is Chief Resident at University of Missouri–Kansas City; Furman S. McDonald, MD, is Program Director and Associate Professor at the Mayo Clinic; and Brent W. Beasley, MD, is Associate Professor of Medicine and Program Director of Internal Medicine at University of Missouri–Kansas City.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the efforts of the Mayo Clinic Survey Research Center for assistance with survey design and data collection.

References

- 1.Colenda C. C., III The psychiatry Chief Resident as information manager. J Med Educ. 1986;61(8):666–673. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198608000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin L. F., Asher E. F., Richardson J. D., Polk H. C., Jr Life after general surgery residency: subsequent practice patterns of chief residents. South Med J. 1984;77(12):1548–1550. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198412000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilder J. F., Plutchik R., Conte H. R. The role of the Chief Resident: expectations and reality. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133(3):328–331. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain S. S., DeLisa J. A., Campagnolo D. Chief Residents in physiatry. Expectations v training. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;72(5):262–265. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoller J. K., Rose M., Lee R., Dolgan C., Hoogwerf B. J. Teambuilding and leadership training in an internal medicine residency training program. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):692–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao D. C., Wright S. M. National survey of internal medicine residency program directors regarding problem residents. JAMA. 2000;284(9):1099–1104. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.9.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Susman J., Gilbert C. Family medicine residency directors' perceptions of the position of Chief Resident. Acad Med. 1992;67(3):212–213. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199203000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg D. N., Huot S. J. Middle manager role of the chief medical resident: an organizational psychologist's perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(12):1771–1774. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0425-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser E. M., Kothari N., Stagnaro-Green A. Chief Residents as educators: an effective method of resident development. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20(4):323–328. doi: 10.1080/10401330802384722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Census Bureau. Census regions and divisions of the United States. Available at: http://www.census.gov/geo/www/us_regdiv.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2008.

- 11.American Board of Internal Medicine. Residency program pass rates 2004–2006. Available at: http://www.abim.org/pdf/pass-rates/residency-program-pass-rates.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2007.

- 12.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accreditation data system. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/adspublic. Accessed April 15, 2009.

- 13.Chaudhry S. I., Caccamese S. M., Beasley B. W. What predicts residency accreditation cycle length? Results of a national survey. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):356–361. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819707cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Internal medicine program requirements. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/RRC_140/140_prIndex.asp. Accessed April 20, 2009.

- 15.Ebell M. H. Future salary and U.S. residency fill rate revisited. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1131–1132. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfsthal S. D., Beasley B. W., Kopelman R., Stickley W., Gabryel T., Kahn M. J. Benchmarks of support in internal medicine residency training programs. Acad Med. 2002;77(1):50–56. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200201000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhry S. I., Caccamese S. M., Beasley B. W. What predicts residency accreditation cycle length? Results of a national survey. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):356–361. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819707cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodenheimer T. Primary care—will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):861–864. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]