Abstract

In order to examine race-ethnic differences in the lifetime prevalence rates of common anxiety disorders, we examined data from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). The samples included 6,870 White Americans, 4,598 African Americans, 3,615 Hispanic Americans, and 1,628 Asian Americans. White Americans were more likely to be diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder than African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Asian Americans. African Americans more frequently met criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder than White Americans, Hispanic Americans and Asian Americans. Asian Americans were also less likely to meet the diagnoses for generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder than Hispanic Americans, and were less likely to receive social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder diagnoses than White Americans. The results suggest that race and ethnicity need to be considered when assigning an anxiety disorder diagnosis, and possible reasons for the observed differences in prevalence rates between racial groups are discussed.

Keywords: Anxiety disorders, cultural differences, epidemiology, National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R), Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Survey (CPES)

Introduction

It has been suggested that cultural identification is strongly associated with the expression of certain anxiety disorders (Hwang & Ting, 2008). There has been a surge in the number of studies focusing on minority mental health issues, and increasing recognition of the need to deepen the understanding of the mental health features of non-White samples versus White samples, in order to make the currently-defined diagnoses more applicable to a range of individuals (Alacón et al., 2009). Yet, while this interest is growing, there still remains a dearth of information about the mental health picture of non-White race-ethnic groups in the United States (Suinn & Borrayo, 2008).

Past studies have primarily documented lower prevalence rates of anxiety disorders in minority groups as compared to their White counterparts. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions is a large epidemiological sample which surveyed over 40,000 people across all 50 states of the United States and over-sampled African Americans and Hispanic Americans in 2001 and 2002. Using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV, it has been reported that the 12-month and lifetime national prevalence of DSM-IV social anxiety disorder (SAD) were 2.8% and 5% respectively, and that being of Asian, Hispanic American, or African American ethnicity is associated with a lower prevalence rate for SAD (Grant et al., 2005a).

Other results from this dataset have indicated a similar pattern in the prevalence of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and panic disorder (Grant et al., 2005b; Grant et al., 2006). Other surveys have found evidence for an elevated rate of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Hispanic cohorts as compared to other minority groups in the U.S. (Pole et al., 2008). In contrast, some findings indicate no differences in prevalence rates between groups of Hispanics and White Americans with regards to panic disorder or SAD (Karno et al., 1989; Katerndahl & Realini, 1993). Thus, there remains quite a mixed picture about how minority mental health relates to the overall prevalence of anxiety disorders in the United States.

The purpose of the present study was to examine differences in the lifetime prevalence rates of anxiety disorders between ethnic and racial minority groups in the U.S. We used the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Survey (CPES) database, an integrated dataset consisting of three national epidemiological studies, to examine reporting of lifetime DSM-IV social anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) across four race-ethnic groups: White Americans, African Americans, Hispanic Americans and Asian Americans. The CPES integrated datasets did not screen for obsessive-compulsive disorder and specific phobia across all three surveys. Therefore, these two anxiety disorders were not included in the analyses.

Method

Participants

The present study utilizes data drawn from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). As described elsewhere(Heeringa et al., 2004), the CPES consists of three national surveys of Americans’ mental health: the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), the National Study of American Life (NSAL), and the National Latino and Asian American Study of Mental Health (NLAAS). The CPES surveys were funded by the National Institute of Mental Heath (NIMH) and the data was collected between May 2002 and November 2003. The survey population in the NCS-R was comprised of adults (≥ 18-years-old), residing in households in the coterminous U.S. Individuals were excluded if they were institutionalized, lived on military bases, or were non-English speakers. A four-stage national area probability sample framework was used to obtain data for the NCS-R, which is a designed to be a cross-sectional replication of the original 1993 National Comorbidity Survey(NCS; Kessler et al., 1994; Kessler & Merikangas, 2004). The NCS-R screening interview was completed by 11,222 households, resulting in an initial 98% response rate. Interviews were conducted in person with 9,282 respondents (47.4% male; 52.6% female) with the mean age of respondents equaling 44.73 years (SD = 17.5), and a response rate of 70.9% (Kessler & Merikangas, 2004).

The NSAL is an integrated household probability sample survey of 3,570 African–Americans, 1,006 non-Hispanic Whites, and 1,623 African American adults of Caribbean descent, for a total interviewed sample of 6,199 participants, with an overall response rate of 71.5% (Heeringa et al., 2004). The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the NSAL were identical to those of the NCS-R, described above. Moreover, this survey was added to the CPES combined dataset in order to obtain information from Afro-Caribbean adults, a group that was not represented in the NCS-R. A similar four-stage national area probability sampling procedure as employed in the NCS-R was utilized to collect the data, with the addition of the special supplement for Afro-Caribbean adults.

The NLAAS, a nationally representative survey of Latino and Asian Americans residing in the U.S., included individuals whose primary language was English, Spanish, or 1 of 3 Asian languages (Chinese, Vietnamese, or Tagalog). Of note, this was the only survey in the CPES combined dataset that utilized trained bilingual interviewers to conduct the full assessment in one of these five languages, as compared to English-only assessments in the NCS-R and NSAL. Moreover, the NLAAS survey population included Latino and Asian-American adults (≥ 18-years-old), in the coterminous U.S., Alaska, and Hawaii. Exclusion criteria were the same as for the NCS-R and the NSAL. Additionally, the study utilized a similar four-stage national area probability sample with special supplements for adults of Puerto Rican, Cuban, Chinese, Filipino, and Vietnamese origin. The Latino sample (n = 2,554) consisted of 4 ethnic subgroups determined by respondents’ self-reported ethnicity: Cuban, Puerto Rican, Mexican and other; the final weighted response rate for the Latino sample was 75.5% (Alegría et al., 2004a). The Asian sample consisted of individuals identifying as Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese or other Asian ancestry (n = 2,095); the combined weighted response rate for the Asian sample was 65.6% (Abe-Kim et al., 2007).

Across the three surveys, study procedures were explained to all participants and written informed consent was obtained from the respondents in English (NCS-R and NSAL), or their preferred language (NLAAS)(Alegría et al., 2007). Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews with all participants in the core and high-density samples (see below), except when a telephone interview was conducted with the respondent. To ensure quality control in each survey, participants were randomly re-contacted to validate the data. An initial $50 incentive was later increased to $150 to address non-response (Abe-Kim et al., 2007).

The sampling procedure for all three surveys has been documented elsewhere (Alegría et al., 2004a; Heeringa et al., 2004) and included 4 stages: 1) core sampling, in which primary sampling units (metropolitan statistical areas or county units) and secondary sampling units (continuous groupings of census blocks) were selected with probability proportionate to size; 2) high–density supplemental sampling to oversample census block groups with 5% or greater density of target ancestry/racial groups; 3) screening of a random selection of housing units (using predetermined sampling rate) within each designated sampling unit to determine satisfaction of study eligibility criteria, followed by random selection of one respondent from each household for the study interview; 4) second respondent sampling to recruit participants from households in which one eligible member had already been interviewed. Weighting correlations were developed to take into account the joint probabilities for selection under the 4 components of the sample design(Abe-Kim et. al., 2007).

Measures

Psychiatric disorder prevalence rates were evaluated with the World Mental Health Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization Composite International Interview (WMH-CIDI), a fully structured lay-administered diagnostic interview that generates DSM-IV diagnosis(Alegria et al., 2007). The diagnoses in earlier versions of the English and Spanish CIDI diagnostic assessments were consistent with the diagnosis made independently by trained clinical interviewers(Rubio-Stipec et al., 1999; Wittchen, 1994). In the present report, we focused on lifetime prevalence rates for SAD, GAD, PD and PTSD for each of four race-ethnic groups: the Asian American subgroup (n = 1,628), consisting of respondents identifying as Chinese, Filipino, or Vietnamese; the African American subgroup (n = 4,598), which included all origins with the exception of Caribbean African; the Hispanic subgroup (n = 3,615), which included all individuals of Hispanic descent with the exception of Spanish and Portuguese; and the White subgroup (n = 6,870).

Statistical Analyses

The complex samples module of SPSS 17.0 was used to complete all analyses for the present report, in order to adequately the weighted nature of the CPES data as described above. Logistic regressions (odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals) were conducted for prevalence of lifetime DSM-IV diagnoses across six ethnic comparisons: White Americans versus Asian Americans, White Americans versus Hispanic Americans, White Americans versus African Americans, Asian Americans versus Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans versus African Americans, and Hispanic Americans versus African Americans. Three covariates were included in the final analyses: age, gender, and annual household income. Education was considered as a potential fourth covariate, but seemed redundant to include in the analyses given its significant positive correlation to annual household income level in the datasets.

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of each of the four racial groups. The White sample was the oldest (M = 46.48), whereas the African American cohort consisted of the highest proportion of women (63.9% female). Asian Americans had the highest average level of household income ($70,686). Each demographic variable was found to be significantly different across each racial group. To account for these differences across groups, all demographic variables were entered as covariates in the logistic regression analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic variables of the racial groups

| Racial Group | N | Age (Mean) | Gender (% females) | Household Income (Yearly Mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Americans | 6.870 | 46.48 | 54.31% | $62,170 |

| African Americans | 4,598 | 42.70 | 63.85% | $33,537 |

| Hispanic Americans | 3,615 | 39.67 | 55.77% | $46,618 |

| Asian Americans | 1,628 | 42.16 | 53.19% | $70,686 |

Note: The Table shows number of participants (n), participants’ mean age, percent of female participants (%F), and mean household income.

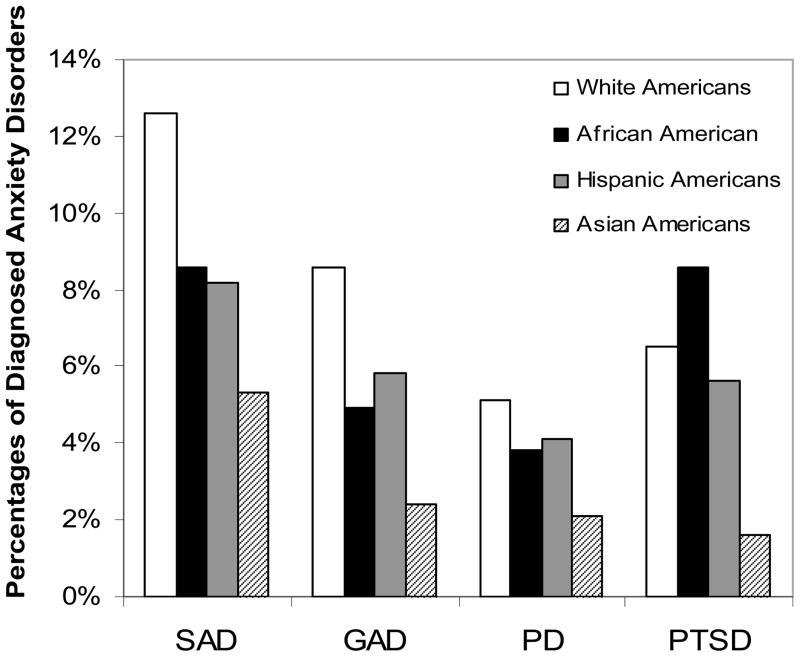

Figure 1 shows the prevalence rates of DSM-IV social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder for each individual racial group. As was found across a range of psychiatric disorders, Asian Americans consistently endorsed symptoms of all four anxiety disorders less frequently than any of the other racial groups. White Americans consistently endorsed symptoms of SAD (12.6%), GAD (8.6%) and PD (5.1%) more frequently than African Americans (8.6%, 4.9%, 3.8%, respectively), Hispanic Americans (8.2%, 5.8%, 4.1%, respectively), and Asian Americans (5.3%, 2.4%, 2.1%, respectively). African Americans more frequently met criteria for PTSD (8.6%) as compared to the White American subgroup (6.5%), Hispanic Americans (5.6%), and Asian Americans (1.6%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of DSM-IV diagnoses across racial groups (SAD = social anxiety disorder, GAD = generalized anxiety disorder, PD = panic disorder, PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder).

Table 2 shows the comparisons of odds ratios between the different ethnic groups in diagnosis of the four anxiety disorders when controlling for gender, age, and socioeconomic status. Logistic regressions revealed that even after controlling for demographic variables that White Americans were significantly more likely to endorse symptoms of all four anxiety disorders than any of the three minority racial groups, with the exception of PTSD. The African American cohort had a significantly higher chance of being diagnosed with PTSD than the Asian-American or Hispanic sample. Asian Americans were less likely to be diagnosed with GAD and PTSD than the Hispanic subgroup. These differences in the reporting of anxiety symptoms remained significant even after a Bonferroni correction to adjust for alpha inflation given the number of pair wise comparisons was made (p < 0.05/24 = 0.002).

Table 2.

Comparison between racial groups in DSM-IV diagnosis of anxiety disorders.

| White Americans vs. Asian American | White Americans vs. Hispanic Americans | White Americans vs. African Americans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-level | OR (95% CI) | P-level | OR (95% CI) | P-level | |

| SAD | 2.490* (1.896–3.269) | p<0.001 | 1.969* (1.628–2.382) | p< 0.001 | 1.789* (1.523–2.101) | p< 0.001 |

| GAD | 0.254* (0.176–0.368) | p<0.001 | 2.208* (1.761–2.767) | p<0.001 | 2.227* (1.828–2.713) | p< 0.001 |

| PD | 2.441* (1.592–3.743) | p<0.001 | 1.572* (1.214–2.035) | p<0.001 | 1.701* (1.353–2.140) | p< 0.001 |

| PTSD | 4.031* (2.432–6.680) | p<0.001 | 1.698* (1.331–2.166) | p<0.001 | 0.923 (0.762–1.117) | ns |

| Asian Americans vs. Hispanic Americans | Asian Americans vs. African Americans | Hispanic Americans vs. African Americans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-level | OR (95% CI) | P-level | OR (95% CI) | P-level | |

| SAD | 0.723 (0.524–0.997) | ns | 0.700 (0.511–0.958) | ns | 0.942 (0.767–1.157) | ns |

| GAD | 0.457* (0.293–0.711) | p< 0.001 | 0.581 (0.384–0.881) | ns | 1.018 (0.792–1.309) | ns |

| PD | 0.605 (0.385–0.952) | ns | 0.699 (0.434–1.126) | ns | 1.094 (0.815–1.468) | ns |

| PTSD | 0.334* (0.197–0.568) | p< 0.001 | 0.211* (0.127–0.351) | p<0.001 | 0.525* (0.419–0.658) | p<0.001 |

Note: The table shows odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and the statistical significance level comparing the first group vs. the second group; ns: not significant at p < .05. All analyses include gender, age, and socioeconomic status as covariates.

significant after a Bonferroni correction of 0.05/24 = 0.002; ns: not significant at p < .05. SAD = social anxiety disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; PD = panic disorder; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

Our results indicate that individuals from minority groups, especially Hispanic or Asian respondents, are less likely to meet criteria for many of the anxiety disorders than White Americans. African Americans are also less likely to endorse criteria for GAD, PD, and SAD, but are more likely to meet diagnosis for PTSD. Across the board, Asian Americans endorsed less anxiety symptomatology, regardless of type, whereas White Americans presented with increased rates of the anxiety disorders examined (except for PTSD) as compared to the three minority groups. These findings held even when demographic variables such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status were accounted for by including them as covariates in the analyses. These results support the findings of the other few large-scale epidemiological studies that have considered cross-ethnic differences in prevalence rates of single disorders(Grant et al, 2005a, b; Grant et al, 2006).

The CPES integrated database provides a unique bank of information on a representative population of the United States, along with a much-needed over-sampling of Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, and African Americans to directly counter the traditional methodological problems of unequal sample sizes typically encountered with research on minority racial groups. To our knowledge, this is the first study that systematically examined the prevalence rates of anxiety disorders where minority groups are not only compared to a White cohort, but to each other as well. Also, the CPES datasets use the WMH-CIDI, which has been shown to be a highly reliable and valid diagnostic instrument for the assessment of DSM-IV disorders(Haro et al., 2006), which, in combination with the sampling design, provide true prevalence rates that are superior to simply analogue measures of various anxiety symptoms.

There remain, however, several questions regarding the mental health picture of various minority groups in the United States. One important consideration is the possibility that the WMH-CIDI does not capture fully accurate endorsement of the disorders studied because of language or cultural differences in the conceptualization of various anxiety symptoms. Indeed, this has been a problem in other screening instruments and methods (Paradis et al., 1994; Johnson et al., 2007) where differences in meaning of worded prompts or biases towards diagnosis of other psychopathology resulted in a decreased validity and reliability of measures that had been previously validated in White samples. The differences seen among racial groups in this study might also indicate inherent deficiencies in the actual diagnostic criteria for the anxiety disorders assessed. That is, perhaps the instrument correctly diagnosed cases with each disorder, but the standards used to make these designations (i.e., current DSM-IV guidelines and specific wording of the criteria) do not capture culturally specific experiences or symptoms of the psychopathology being examined, which may have resulted in an artificial lowering of the prevalence rates of these disorders in certain groups (Alegria et al., 2004b).

That being said, several other studies using non-American samples have found prevalence rates for the various anxiety disorders (particularly social anxiety disorder and panic disorder) to be markedly different to the rates found in large-scale epidemiological studies in the U.S. (Kawakami et al., 2005; WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium, 2004), which more readily indicate methodological flaws, some type of response-bias, or as mentioned above, a difference in the perceived experience of these disorders. One other aspect that may account for differences in prevalence rates for immigrant populations versus their counterparts in native settings is the level of individualistic or collectivist identification of the individuals assessed. Several studies have noted the differences between levels of anxiety in communities aligning themselves with more collectivistic values, where focus on maintaining harmony within the group is of the highest priority, as compared to those adhering the more individualistic cultural attitudes, where individual achievement are most highly valued and rewarded by the rest of the social group (Heinrichs, et al., 2006; Caldwell-Harris & Ayicicegi, 2006; Varela et al., 2004). Thus, an assessment of the degree of adherence to predominantly individualistic or collectivistic values could impact report of anxiety symptoms.

Another area that warrants future research is the impact of acculturative stress (which refers to the stress caused by adjusting to a new cultural environment) on the development of psychopathology, as well as other related variables such as group identification. Several studies have suggested that while a greater identification with one’s minority racial or cultural status is associated with higher levels of collective self esteem (Kim & Omizo, 2006), it is conversely related to a higher endorsement of psychological distress such as clinical depression(Hwang & Ting, 2008) and PTSD symptoms(Khaylis et al., 2007). Yet, most studies have not directly studied the effects of acculturative stress on mental health outcomes, and the few that have done so have indicated a limited independent effect of acculturative stress on psychological disorders. Clearly, the impact of this factor needs to be more directly examined. A measure of acculturative stress was utilized in a portion of the CPES combined dataset, but could not be included as a covariate in the analyses because of its omission from the NCS-R portion of the data, from which the White American group was being assessed. An array of other variables (such as number of years in the U.S., citizenship status, and subjective feeling of affinity towards the U.S.) were considered as potential proxies for this measure, but none of these were systematically assessed across all three datasets for all racial groups. This raises important considerations for future methodological designs and underscores the urgency in obtaining data in a more cross-racially sensitive fashion.

Conclusions

In order to examine race-ethnic differences in the lifetime prevalence rates of common anxiety disorders, we examined prevalence data for social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) for four race-ethnic groups: White Americans, African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Asian Americans. Statistical analyses revealed that White Americans were more likely that the minority groups to be diagnosed with all the disorders examined, with the exception of post-traumatic stress disorder, which was most prevalent in African Americans. Asian Americans were also generally less likely to meet diagnosis for all disorders examined than the other racial groups. The results suggest that race and ethnicity need to be considered when assigning an anxiety disorder diagnosis.

Future studies should examine rates of disorders across ethnic groups in datasets that allow the individual to respond in their native language; some of the data sets included in our analysis did not do so. Otherwise, the sample will be slanted to acculturated groups, and potentially important cultural influence on psychopathology will be reduced(Cintrón et al., 2005). Furthermore, even though the assessments were at least conducted in five different languages to participants in the NLAAS survey, the members within each racial group are not homogenous: African Americans in the South versus African Americans in the North versus African Americans of Caribbean origin; Mexican-Americans versus Puerto Ricans (e.g., Puerto Ricans have significantly higher rates of anxiety disorders than Mexican-American populations; Alegría et al., 2007) and three Asian groups in the data sets. Thus, future studies should further examine the rate of disorders taking into consideration degree of acculturation(Breslau et al., 2007). In addition, future studies should examine rates of anxiety disorders across specific subgroups, such as Puerto Ricans versus Mexican-Americans, or Japanese Americans versus Filipino Americans.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hofmann is a paid consultant by Schering-Plough and supported by NIMH grant 1R01MH078308. Dr. Hinton is supported by NIMH grant R01MH079032.

References

- Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, Spencer MS, Appel H, Nicado E, Alegría M. Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: Results from the National Latino and Asian-American study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:91–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alacón RD, Becker AE, Lewis-Fernández R, Like RC, Desai P, Foulks E, Gonzales J, Hansen H, Kopelowicz A, Lu FD, Oquensdo MA, Primm A. Issues for DSM-V: The role of culture in psychiatric diagnosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197:559–560. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b0cbff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, Polo A, Cao Z, Canino G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2004a;97:68–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Takeuchi D, Canino G, Duan N, Shrout P, Meng X, Vega W, Zane N, Doryliz V, Woo M, Vera M, Guarnaccia P, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Sue S, Escobar J, Lin K, Gong F. Considering context, place and culture: The National Latino and Asian American Study. Int J Method Psych Res. 2004b;13:208–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo M, Torres M, Gao S, Oddo V. Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: Results from the National Latino and Asian-American study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:76–82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Borges G, Kendler KS, Su M, Kessler RC. Risk for psychiatric disorder among immigrants and their US-born descendants: Evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:189–195. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243779.35541.c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell-Harris CL, Aycicegi A. When personality and culture clash: the psychological distress of allocentrics in an individualist culture and idiocentrics in a collectivist culture. Transcult Psych. 2006;43(3):331–361. doi: 10.1177/1363461506066982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintrón JA, Carter MC, Suchday S, Sbrocco T, Gray J. Factor structure and construct validity of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index among island Puerto Ricans. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19:51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant DF, Hasin DS, Blanco C, Stinson FS, Chou P, Goldstein RB, Dawson DA, Smith S, Saha TD, Huang B. The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005a;66:1251–1361. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Smith SM, Saha TD, Huang B. Prevalence, correlates, co-morbidity, and comparative disability of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the USA: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2005b;35(12):1747–1759. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Smith SM, Huang B, Saha TD. The Epidemiology of DSM-IV Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia in the United States: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(3):363–374. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, De Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Lepine JP, Mazzi F, Reneses B, Vilagut G, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Int J Meth Psych Res. 2006;15(4):167–180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) Int J Meth Psych Res. 2004;13:221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs N, Rapee RM, Alden LA, Bogels S, Hofmann SG, Oh KJ, Sakano Y. Cultural differences in perceived social norms and social anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WC, Ting JY. Disaggregating the effects of acculturation and acculturative stress on the mental health of Asian Americans. Cult Divers Ethnic Min Psychol. 2008;14:147–154. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MR, Hartzema AG, Mills TL, De Leon JM, Yang M, Frueh C, Santos A. Ethnic differences in the reliability and validity of a panic disorder screen. Ethnic Health. 2007;12(3):283–296. doi: 10.1080/13557850701235069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karno M, Golding JM, Burnam AM, Hough RL. Anxiety disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Whites in Los Angeles. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177(4):202–209. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198904000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katerndahl DA, Realini JP. Lifetime prevalence of panic states. Am J Psych. 1993;150(2):246–249. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami N, Takeshima T, Ono Y, Uda H, Hata Y, Nakane Y, Nakane H. Twelvemonth prevalence, severity, and treatment of common mental disorders in communities in Japan: Preliminary findings fro the World Mental Health Japan Survey 2002–2003. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:441–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS–R): Background and aims. Int J Meth Psych Res. 2004;13:60–65. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalys A, Waelde L, Bruce E. The role of ethnic identity in the relationship of race-related stress to PTSD symptoms among young adults. J Traum Diss. 2007;8(4):91–105. doi: 10.1300/J229v08n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Omizo MM. Behavioral acculturation and enculturation and psychological functioning among Asian American college students. Cult Divers Ethnic Min Psychol. 2006;12:245–258. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis CM, Hatch M, Friedman S. Anxiety disorders in African Americans: An update. J Natl Med Assoc. 1994;86(8):609–612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pole N, Gone JP, Kulkarni M. Posttraumatic stress disorder among ethnoracial minorities in the United States. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15(1):35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Stipec M, Peters L, Andrews G. Test-retest reliability of the computerized CIDI (CIDI-Auto): Substance abuse modules. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(12):1569–1579. doi: 10.1080/08897079909511411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suinn RM, Borrayo EA. The ethnicity gap: The past, present, and future. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39(6):646–651. [Google Scholar]

- Varela RE, Vernberg EM, Sanchez-Sosa JJ, Riveros A, Mitchell M, Mashunkashey M. Anxiety reporting and culturally associated interpretation biases and cognitive schemas: a comparison of Mexican, Mexican American, and European American families. J Clin Child Adol Psychol. 2004;33:237–247. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Prevalence, Severity, and Unmet Need for Treatment of Mental Disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psych Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]