Abstract

Atmospheric dynamics strongly influence the migration of flying organisms. They affect, among others, the onset, duration and cost of migration, migratory routes, stop-over decisions, and flight speeds en-route. Animals move through a heterogeneous environment and have to react to atmospheric dynamics at different spatial and temporal scales. Integrating meteorology into research on migration is not only challenging but it is also important, especially when trying to understand the variability of the various aspects of migratory behavior observed in nature. In this article, we give an overview of some different modeling approaches and we show how these have been incorporated into migration research. We provide a more detailed description of the development and application of two dynamic, individual-based models, one for waders and one for soaring migrants, as examples of how and why to integrate meteorology into research on migration. We use these models to help understand underlying mechanisms of individual response to atmospheric conditions en-route and to explain emergent patterns. This type of models can be used to study the impact of variability in atmospheric dynamics on migration along a migratory trajectory, between seasons and between years. We conclude by providing some basic guidelines to help researchers towards finding the right modeling approach and the meteorological data needed to integrate meteorology into their own research.

Introduction

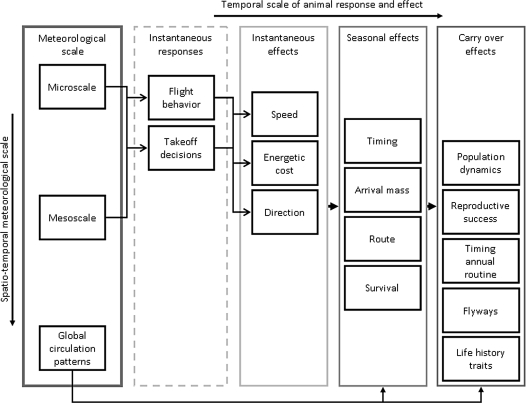

For flying organisms, such as insects, bats and birds, atmospheric dynamics play an important role in their migratory movements (e.g. Richardson 1990; Dingle 1996; Liechti 2006; Kunz et al. 2008). Animals move through a dynamic and heterogeneous environment where conditions from the microscale through the mesoscale and even global circulation patterns are relevant (Drake and Farrow 1988; Nathan et al. 2005; Kunz et al. 2008). The effects of atmospheric dynamics on migration are complex and may differ depending on the temporal and spatial scale being considered as well as on the species, region, season and year. For example, instantaneous responses to changing wind speeds due to microscale and/or mesoscale dynamics may affect the flight speed, course and energetic cost at that point in time, as well as the conditions that will be experienced later en-route (e.g. Chapman et al. 2010; Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2010). These effects may also be cumulative throughout the season, finally resulting in carry-over effects such as an impact on survival (e.g. Erni et al. 2005; Newton 2006), timing of migration or breeding success. Although global patterns of atmospheric circulation may not affect instantaneous responses of individual migrants directly, they will shape atmospheric conditions at smaller scales. At the same time they are likely to have more long term and cumulative effects on migration by affecting migration routes and seasonal timing of long distance movements. We provide a simplified representation of these multi-scale interactions in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A simplified representation of the different spatio-temporal scales of atmospheric dynamics that may influence instantaneous behavioral responses, resulting in short-term (instantaneous) and longer-term effects. Carry-over effects include not only inter-annual effects (e.g. population size or breeding success), but longer-term effects that may have evolutionary consequences (e.g. shaping migration routes). For example, instantaneous changes in flight behavior would influence instantaneous flight speed, the timing of migration within a migration season and could also lead to carry-over effects such as the timing of breeding or breeding success.

Meteorology should be integrated into research on migration, especially when trying to understand natural variability observed in aspects like the timing of migration; migratory routes; orientation; use of stopover sites; or population trends such as effects on survival or breeding success as a result of changes in arrival time or physiological condition. Meteorology is also of interest at longer time scales when trying to understand the evolution of particular migratory systems. Thus, integrating meteorology and research on animal migration will help us better understand both short- and long-term organismal–environmental linkages, one of the grand challenges identified in organismal biology (Schwenk et al. 2009). However, linking mechanisms at the individual level to these longer-term, or larger-scale consequences remains challenging.

During the past few decades numerous empirical and theoretical studies have addressed the influence of atmospheric dynamics on animals’ migrations (for overviews see Richardson 1978, 1990; Drake and Farrow 1988; Dingle 1996; Liechti 2006; Newton 2008). Atmospheric conditions are known to influence the onset of migration (Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2006; Gill et al. 2009), migration phenology (Hüppop and Hüppop 2003; Jonzen et al. 2006; Bauer et al. 2008), stopover decisions (Åkesson and Hedenström 2000; Dänhardt and Lindström 2001; Schaub et al. 2004; Wikelski et al. 2006; Brattström et al. 2008), flight speeds (Garland and Davis 2002; Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2003a; Kemp et al. in review), flight altitudes (Bruderer et al. 1995; Wood et al. 2006, 2010; Reynolds et al. 2009; Schmaljohann et al. 2009), flight strategy (Gibo and Pallett 1979; Pennycuick et al. 1979; Gibo 1981; Spaar and Bruderer 1997; Spaar et al. 1998; Sapir 2009), orientation and trajectories (Thorup et al. 2003; Chapman et al. 2008; Srygley and Dudley 2008; Chapman et al. 2010), migration intensity or probability (Erni et al. 2002; Reynolds 2006; Cryan and Brown 2007; Stefanescu et al. 2007; van Belle et al. 2007; Leskinen et al. 2009), as well as migratory success (Erni et al. 2005; Reilly and Reilly 2009).

Modeling approaches

Different modeling techniques have been used to study the influence of atmospheric dynamics on migration. We would like to distinguish between ‘concept-driven’ and ‘data-driven’ models. The structure of concept-driven models can only be conceived if extensive prior knowledge of the system is available and cannot be discovered in an automated fashion. Calibration of parameters of concept-driven models is possible if measurements of model output are available, but this is not always required to use the model. Reasonable values of parameters can often be found by using expert knowledge or information from experiments or biophysical calculations. Concept driven models can then be run as thought experiments, without any observations.

The structure of data-driven models, however, can be derived via (highly) automated procedures but does not necessarily represent cause and effect relations in nature. These models need relatively little prior knowledge of the system before they can be constructed, but always require calibration of the parameters because the parameters do not necessarily match physical entities that can be independently observed in nature. Because of the necessity to calibrate, data-driven models always need observations on both input and output variables of the model.

Table 1 specifies three different types of concept-driven modeling techniques and two different types of data-driven modeling techniques with some of their main characteristics. These definitions are of course not specific for models of migration, but are applicable to ecological models in general. Table 2 provides several examples of the various techniques of measurement and modeling applied in studying the influence of atmospheric dynamics on migration.

Table 1.

An overview of different types of concept- and data-driven models and their characteristics

| Requirement for creating the model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Description | Conceptual understanding of the system | Numerical and data processing skills | Observations on state variables | Possibilities for calibration | Frequency of use |

| Concept-driven | ||||||

| SC | Static Concept-based modela | Intermediate | Low | Few | Easy, many methods | Intermediate |

| DI | Dynamic IBMb | Intermediate | Intermediate | Intermediate | Difficult, few methods | Intermediate |

| DC | Dynamic Continuum-based modelb | High | High | Intermediate | Intermediate, few methods | Low |

| Data-driven | ||||||

| SD | Static Data-based model | Low | Low | Intermediate | Easy, many methods | High |

| DD | Dynamic Data-based model | Low | High | Many | Intermediate, few methods | Low |

Frequency of use in migration studies is provided in the last column; for references to specific studies see Table 2.

aIn this context, static means that the process being studied is either in steady state or that there is no influence of previous states on the current state.

bIndividual-based: model state variables refer to properties of an individual; continuum based: model state variables refer to population properties. State variables are model-entities which are updated at each model time step with a difference equation in dynamic models and are usually comparable to the dependent variables in static models.

Table 2.

A selection of studies on the influence of atmospheric conditions on animal migration, including focal species or group, types of data used, geographic region of study, type of model, and relevant reference

| Effects on migration | Species/group | Migration data | Meteorological variable: data source | Geographic region | Model type | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flight behavior: altitude | Nocturnal migratory birds | Tracking radar | Winda: radiosonde NCEP reanalysis data | Sahara | SC | Schmaljohann et al. 2009 |

| Flight behavior: altitude | Soaring avian migrantsb | Motorized glider | Boundary layer height and vertical lift: boundary layer convective model | Israel | SD | Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2003b,c |

| Flight behavior: altitude | Nocturnal migratory insects | Radar | Various: numerical weather prediction model, the Unified Model | UK | SD | Wood et al. 2010 |

| Take off decisions | Arctic geese | Ringing data | Onset of spring proxy: NDVIc | Palearctic flyway | DI | Bauer et al. 2008 |

| Take off decisions | Bar tailed godwit | Satellite telemetry | Sea level pressure, winda: NCEP reanalysis data GEOS-5 global atmospheric model | Pacific ocean flyway | Descriptive no computer model | Gill et al. 2009 |

| Take off decisions | Not relevant | None | Wind assistance or no assistance: no data | Not relevant | SC | Weber et al. 1998 |

| Take off decisions | Green darners | Radio telemetry | Winda and temperature: weather station observations | Northeast USA | SD | Wikelski et al. 2006 |

| Migration intensityd | Nocturnal migratory birds | Radar | Winda, barometric pressure, temperature, precipitation: weather station observations | The Netherlands | SD | van Belle et al. 2007 |

| Migration intensityd | Nocturnal passerine migration | Radar and visual observations | Winda, temperature, synoptic weather index: weather station observations | Southeastern USA | SD | Able 1973 |

| Migration intensity | Black-cherry aphids and diamond-back moths | Radar and insect traps | Winda: HIRLAM and ECMWF numerical weather prediction models | Finland | DC | Leskinen et al. 2009 |

| Speed | Turkey vulture | Satellite telemetry | Wind speed, turbulent kinetic energy, cloud height: North American regional reanalysis data | Eastern North American flyway | DD | Mandel et al. 2008 |

| Speed | Red knots | Visual observations | Winda: NCEP reanalysis data | Afro–Siberian flyway | DI | Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2010 |

| Direction/Orientation | Reed warbler | Radio telemetry | Winda: weather station observations | Sweden | SD | Åkesson et al. 2002 |

| Direction/Orientation | Moths and butterflies | Radar | Winda: numerical weather prediction model, the Unified Model | UK | SD | Chapman et al. 2010 |

| Timing | Soaring avian migrantsb | Visual observations, Satellite telemetry | Barometric pressure, temperature, precipitable water: NCEP reanalysis data | Western Palearctic (eastern) flyway | SC | Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2006 |

| Timing | Passerine migrants | Ringing data | North Atlantic Oscillation | Europe and Scandinavia | SD | Jonzen et al. 2006 |

| Arrival mass | Western sandpipers | Biometric measurements | Winda: weather station observations | North American Pacific Coast | DI | Butler et al. 1997 |

| Route | Silver Y (noctuid moth) | Radar | Winda: numerical weather prediction model, the Unified Model | United Kingdom, Northwest Europe | DI | Chapman et al. 2010 |

| Route | Golden Eagles | Visual observations | Wind (implicit): digital elevation model | Central Pennsylvania | DC | Brandes and Ombalski 2004 |

| Survival | Simulated nocturnal passerine migrant | Literature | Winda: NCEP reanalysis data | Western Palearctic migration | DI | Erni et al. 2005 |

| Mass, population dynamics | Houbara bustard Stonechat | Literature | Winter severity (implicit): no data | Not directly relevant | DC | Stöcker and Weihs 1998 |

Type of model is described in more detail in Table 1. The terms used in the column entitled ‘Effects on migration’ are adapted to roughly follow the framework provided in Fig. 1 for comparative purposes and, thus, do not always follow the exact terms used in the original study. Similarly, although many effects may be studied with one model, we generally highlight the effect that was the focus of the study. For suggestions on where to find different sources of meteorological data, some of which are mentioned in this table, see Table 3.

aWind speed and direction.

bWhite stork, honey buzzard, lesser spotted eagle.

cNDVI, normalized difference vegetation index.

dMigration intensity can also be considered a proxy for takeoff decisions.

We think that especially concept-driven dynamic simulations of migration provide a suitable framework for integrating scattered knowledge about migration, systematically addressing complex questions about system feedbacks and scale, comparing theories and observations, and identifying avenues for new research. By modeling the influence of atmospheric conditions en-route we can study emergent patterns of migration at the individual and population level as well as study the importance of the variability in individual behavior and the variability in atmospheric conditions, between days, seasons, years or regions. The models are tools to better understand underlying mechanisms, but not goals in themselves. In such models, measurements gathered from field research or from laboratory experiments can either be implicitly integrated into the models to formulate model assumptions and to parameterize models, or explicitly to compare to model results. Furthermore, atmospheric conditions from observations, reanalysis data, numerical models, or artificial data (see Table 3 for examples) are needed as input to the models.

Table 3.

An overview of the most relevant temporal scales (indicated by an X) for different types of meteorological data that can be incorporated into models of bird migration. Examples of on-line resources for such data are also provided

| Temporal scale | Large eddy simulation | Regional numerical mesoscale models | Station observations | Global/continental reanalysis data | Global circulation indices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minutes | X | X | – | – | – |

| Hourly | – | X | X | X | – |

| Daily | – | X | X | X | – |

| Seasonal | – | – | X | X | X |

| On-line resource | Generally none | MM5a | ECA&Db | NCEP reanalysis datac | NAO indexd |

The higher the spatial and temporal resolution of the data, generally the harder it is to find on the internet and such models must be run for the study of interest.

aPSU/NCAR mesoscale model (MM5); http://www.mmm.ucar.edu/prod/rt/pages/rt.html; Grell et al. 1994.

bECA&D European climate and assessment dataset; http://eca.knmi.nl/; Klok and Klein Tank 2009.

cNCEP-NCAR reanalysis data; http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/reanalysis/reanalysis.shtml; Kalnay et al. 1996.

dNAO (North Atlantic Oscillation) index; http://www.cgd.ucar.edu/cas/jhurrell/indices.html; Hurrell et al. 2003.

In this article we describe the development and application of two studies using dynamic models of migration (‘concept-driven’, dynamic individual-based models; DI, Table 1) as examples of how and why to integrate meteorology into research on migration. We use the models to better understand underlying mechanisms at the individual level to help explain the patterns that emerge at the population level. We provide some basic guidelines to help researchers towards integrating meteorology into their research on migration and we discuss the opportunities and limitations of different sources of data that can be used for such studies. We thus hope to facilitate further integration of field biology, meteorology and modeling.

Case study of the migration of red knots: The importance of wind

From numerous studies over the years it is clear that of all atmospheric conditions wind plays the most important role in avian migration (Åkesson and Hedenström 2000; Åkesson et al. 2002; Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2003a; van Belle et al. 2007; Schmaljohann et al. 2009; Kemp et al. in review; for review see Liechti 2006). Yet, quantifying the cumulative effect of wind en-route for an entire migration trajectory, as well as the effect of variability in space and time has rarely been done in avian research (Stoddard et al. 1983; Erni et al. 2005; Vrugt et al. 2007; Reilly and Reilly 2009).

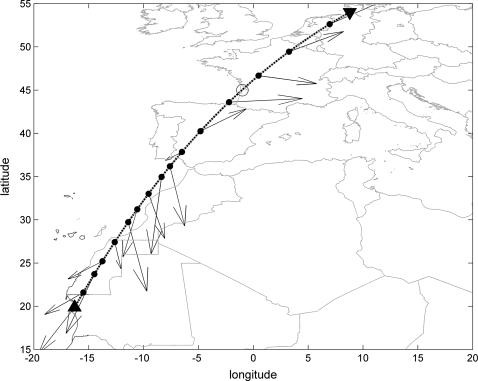

The Afro–Siberian red knot (Calidris canutus canutus) is an intensively studied long-distance migrant (e.g. Piersma et al. 1992; Piersma and Lindström 1997; van de Kam et al. 2004). These birds migrate north in two non-stop flights of approximately 4400 km each from their wintering grounds in Mauritania via the German Wadden Sea to the Siberian breeding grounds in only four weeks (Piersma et al. 1992; van de Kam et al. 2004). From previous studies, favorable winds were considered essential along this flyway (Piersma and van de Sant 1992). Field observations have shown that red knots erratically use an extra stopover site on the French Atlantic coast (Leyrer et al. 2009). One hypothesis to explain this phenomenon was that birds experiencing unfavorable winds would use this area as an emergency stopover site. Therefore, a dynamic individual-based model (IBM) of northbound migration, incorporating winds experienced en-route, was developed to study whether use of this intermediate stopover site could be explained by stochastic wind conditions (Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2010). In the model, birds are moved forward in 6-h time steps along the great-circle route between their wintering site in Mauritania and their stopover site at the Wadden Sea. The wind experienced at the beginning of each time step determines the ground speed of the bird which is subsequently used to calculate flight times and the birds’ locations at the next time step (Fig. 2). Data on speed and direction of wind at four different levels of pressure were used in this study to represent wind conditions experienced at different altitudes during flight. The data were extracted from the global NCEP-Reanalysis dataset which has a spatial resolution of 2.5° × 2.5° and a 6-h temporal resolution (Kalnay et al. 1996). The advantages of the NCEP reanalysis dataset for this type of analysis are the homogenous spatial and temporal coverage, global and long term coverage and free availability on the internet. After running simulations, results from the migration model can be compared to observations.

Fig. 2.

A forward simulation of the migration of red knots taking off on May 1, 1986. Upward-pointing and downward-pointing triangles indicate wintering site (simulated start location) and Wadden sea stopover site (simulated end location) respectively. The open circle marks the location of the emergency stopover site on the French Atlantic coast. Black circles indicate location at each time step. Arrows indicate the speed and direction of the wind at each location and the dotted line shows the flight trajectory. The shorter the distance between circles, the slower is the ground speed due to disadvantageous winds.

A comparison between simulated flight times and the number of birds observed stopping over at the French staging site showed how unpredictable winds affect flight times and that wind is a predominant driver of the use of an emergency stopover site along the French Atlantic coast. Wind clearly plays an important and quantifiable role in this, and probably many other, migratory systems. The study also indicates the importance of this emergency stopover site for conservation. Although the Wadden Sea is an obligatory staging area in this system, the French Atlantic coast may be essential for ensuring the survival of individuals that have encountered very unfavorable winds en-route. Thus, in the long term, this emergency stopover site may influence, and help stabilize, migratory population dynamics. These ideas, however, require further research that can be conducted with appropriate modeling techniques and field measurements.

One of the main advantages of such a modeling framework is the ability to also explore the effect of variability of wind conditions across years, starting dates, and altitudes of flight, all resulting in different wind conditions and flight times. Furthermore, the potential effects of spatial and temporal auto-correlation in wind conditions could be studied along the migratory route. For example, wind conditions experienced in France were spatially and temporally auto-correlated for >18 h and sometimes over hundreds of kilometers. Spatio-temporal correlation in atmospheric dynamics could provide migrants with information on what to expect further along their trajectory and may enable them to fine-tune their decisions based on their physiological state, geographic location, and immediate and expected environmental conditions.

In the future, the model can be extended by integrating the energetics of flight to model the expenditure of energy due to the wind conditions experienced en-route. These results then can be compared to field measurements. The model is not only designed to enable further extensions but can be applied to other species where sufficient data are available. The model framework presented here is quite similar to meteorological trajectory analysis used to estimate the flight paths of migrating insects (e.g. Scott and Achtemeier 1987; Chapman et al. 2010) as a result of meteorological dynamics experienced en-route. Although in contrast to migrating insects, the location of the departure and destination are known for the red knots.

Case study of migration by white storks: The importance of thermal convection

Atmospheric dynamics strongly influence the migration of soaring birds; particularly thermal convection which influences daily flight schedules and migration routes (Kerlinger 1989; Leshem and Yom-Tov 1998), flight speeds (Leshem and Yom-Tov 1996a; Mandel et al. 2008) and flight altitudes (Leshem and Yom-Tov 1996a; Shannon et al. 2002a, 2002b; Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2003b, 2003c). Many soaring species are known to migrate in large single-species or mixed-species flocks aggregating in both space and time (e.g. Kerlinger 1989; Leshem and Yom-Tov 1996a, 1996b). Large-scale aggregations along well established and narrow migratory corridors are often attributed to natural leading lines like the Appalachian Mountains or to circumvention of large bodies of water, resulting in geographic bottlenecks such as those seen in Panama, Gibraltar, the Bosporus and Israel (Kerlinger 1989; Leshem and YomTov 1996b; Bildstein and Zalles 2005; Bildstein 2006). However, the mechanisms that result in small scale convergence and the potential benefits of flocking remain largely unknown. With our model, which is described below, we explore the hypothesis that flocking improves the identification and utilization of thermals (e.g. Kerlinger 1989).

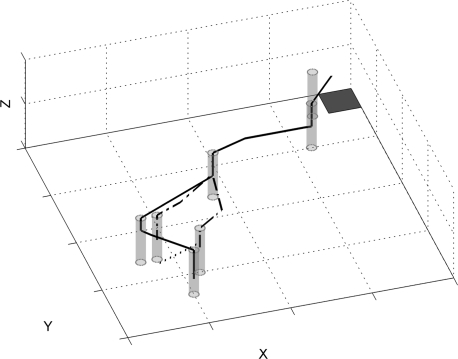

In order to identify the mechanisms leading to convergence and the importance of individual decision rules, a spatially explicit IBM named ‘Simsoar’ was developed to simulate migration of soaring birds (van Loon et al. in review). The model was parameterized for the white stork and for atmospheric conditions in Israel based on extensive information from visual observations, motorized glider flights, radar (e.g. Leshem and YomTov 1996a, 1996b, 1998; Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2003b, 2003c) and satellite telemetry studies on the migration of this species along the eastern Palearctic flyway (e.g. Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2003a, 2006). In the model, birds strive to reach their destination using soaring flight and select thermals based on several physical constraints and on pre-determined behavioral rules which differentiate between thermals with and without birds (Fig. 3). At each time step birds are either climbing in a thermal or gliding to their current target (a thermal or their destination). This design of the model provides a framework for virtual experiments which can be used to explore the patterns that emerge due to different decision rules, flight parameters, convective conditions, or takeoff and destination areas, and to test different scenarios. The study shows that under the convective conditions simulated, social-decision rules lead to stronger convergence and slightly more efficient flight then do non-social decisions. Furthermore, under equally dense thermal fields, the spatial distribution of thermals has a significant impact on the efficiency of migration.

Fig. 3.

3D trajectories of simulated migration of white storks. Thermals are indicated as grey cylinders; the destination is indicated by a gray box. Each trajectory represents the movement of an individual during the simulation. When in a thermal, birds climb vertically until they reach the top; they then glide (losing altitude) towards the next thermal if it can be sensed and reached by the birds. Otherwise the bird glides first to the destination, until another thermal can be utilized. In this simulation, a bird first searches for the most distant thermal containing other birds.

Although the model was initially run with static thermal conditions, the model can be extended in the future with an additional module to simulate dynamic convective conditions (e.g. Allen 2006). Currently, we do not expect to have systematic measurements of individual thermals; however, the model can be parameterized with local meteorological conditions and the properties of landscapes to provide dynamic information on the density of thermals, the areas where thermals are most likely to develop, height of the boundary layer, and vertical lift (e.g. Shannon et al. 2002a, 2002b; Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2003b, 2003c). Simulated spatial and temporal patterns can be compared to field data such as visual observations, radar observations and tracking of individual birds. The model can also be used to compare different avian species or insects that use soaring flight during migration (e.g. Gibo and Pallett 1979; Gibo 1981; Garland and Davis 2002). Furthermore, with the appropriate extensions, the model can be applied to entire migratory trajectories and help identify the mechanisms that lead to regional and seasonal differences in migration.

Using IBMs in research on migration

By developing modeling frameworks with flexible structure and explicit spatial and temporal dynamics we can study the importance of atmospheric conditions and individual decision rules in different migratory systems. In the case studies presented above we showed how studying individual responses to atmospheric dynamics along a trajectory could help explain emergent patterns such as the use of emergency stopover sites or convergence of flight paths as well as understand and quantify the importance of the variability in atmospheric conditions (within a year, along a trajectory, between years, or at different altitudes). The two case studies we presented were examples of dynamic IBMs (DI, Table 1). This is a relatively large and diverse group of models with varying ranges of complexity. Depending on the aim and structure of the model, IBMs may (e.g. the white stork case study), or may not (e.g. the red knot case study), include interactions between individuals. IBMs may also include an aspect of heritability, where traits are transferred between generations and can evolve during a simulation (e.g. Erni et al. 2003). In order to develop these dynamic IBMs, data are essential, not only to parameterize models with information such as flight speeds, departure dates, but also to develop reasonable decision rules. Results from the model, in turn can, and should, be compared to measurements which can be at the individual or population level or consider local or more global patterns. The integration of models and measurements has shown that atmospheric conditions can play a central role in shaping migratory success and efficiency. Often rather simple decision rules can enable animals to adapt to a very dynamic environment.

Guidelines for integrating atmospheric conditions into migration models

For many empirical researchers perhaps the biggest hurdle in such an approach is how and where to get started. Following, we provide some guidelines, and although we provide these in a particular order, the process is often iterative.

(1) Data quantity and quality: Consider the quantity and quality of the available animal and atmospheric data. Data are needed as input for models and to compare with the output from models at the relevant space and time. Table 3 provides a brief overview of what types of meteorological data are available and for which spatial and temporal scales they would be most suitable. It is important to try to consider atmospheric conditions at the temporal and spatial scale most suitable for the ecological processes being studied (Fig. 1, see also Hallett et al. 2004).

(2) Model framework: Consider the aim of your model and select the most suitable modeling framework. When using models to integrate scientific knowledge, there is a major distinction between the aim of making adequate (reliable, accurate and precise, at the right scale) predictions and the aim of enhancing understanding. When the aim is to make adequate predictions, it is generally desirable to match the resolution and extent of the model with the units and domain at which the predictions are required (‘scale of prediction’ for brevity), as well as gather data at the scale of prediction. In this way, errors due to mismatches of scale are avoided. If the scale at which the most important processes operate does correspond with the scale of the prediction, try to build a concept-driven model. However, if the scale at which key processes operate is much finer than the scale of prediction, it will be very hard (if possible at all) to build a concept-driven model from expert knowledge and first principles. In that case a data-driven model is the most suitable option.

In case the aim is to gain understanding about a certain aspect of a migration system, the question becomes relevant whether you are in an explorative or a confirmative phase of your research. In the explorative phase, the aim is to identify patterns, attempt to find cause-and-effect relationships and compare alternative models. Currently it is not feasible to conduct such explorative activities with concept-based models because it requires too much effort to generate a single model. In the future, however, more flexible modeling systems may be built that do, in fact, allow such activities (Taylor et al. 2007). So, data-driven models are the tools of choice in the explorative research phase. When a specific idea or hypothesis can be formulated, research enters a confirmative phase where some sort of formal comparison of that idea against observations or other ideas has to be made. In this phase, both concept- and data-driven models can be used effectively.

Determining which type of model can be used under a given set of research aims and of constraints with regard to availability of data (the variables that are available, as well as their resolution and extent), cannot be answered in general; it depends a lot on the precise nature of a research question. However, Table 1 specifies the main properties and limitations of the various modeling techniques and can provide guidance about which modeling technique to use, after a researcher has specified her/his research question. Table 2 provides some examples of studies of migration with a reference to the different types of model applied.

(3) Communication and collaboration: During this process and the research itself, consider communicating and collaborating with the necessary experts, e.g. modelers or meteorologists. Keep in mind that the models themselves are also vehicles for communication. Communication can be facilitated by developing common terminology and using conceptual frameworks for the description and design of models (e.g. Grimm et al. 2006; Nathan et al. 2008) as well as by research workshops dedicated to collaboration (Bauer et al. 2009).

Future perspectives

Several advances in different fields will strongly facilitate the integration of meteorology into migration research. First, meteorological data are becoming more available and accessible, with numerous sources of data freely available on the internet (Table 3). Some of these sources are even archived globally for several decades (e.g. NCEP-NCAR reanalysis data, Kalnay et al. 1996). More recently, atmospheric models that can provide data at the temporal and spatial scale of interest have been developed and will greatly enhance migration research (Scott and Achtemeier 1987; Nathan et al. 2005). At very fine scales this will often require that atmospheric models are run specifically for the research project (e.g. Shannon et al. 2002a, 2002b; Shamoun-Baranes et al. 2003b, 2003c; Sapir 2009). Advances in technologies to collect data on animal movement (e.g. Robinson et al. in press) will also facilitate the integration of meteorology into migration research. Miniaturization of tracking technologies (e.g. Wikelski et al. 2006,2007; Stuchbury et al. 2009) and collection of precise locations using the Global Positioning system (GPS) improves the tracking of individual animals. High-resolution GPS may help revolutionize this field by providing detailed information on how animals respond to atmospheric dynamics en-route or even to help reveal animals’ decision rules. Furthermore, collecting additional data such as heart rate or 3-axial acceleration can provide information on behavior and the expenditure of energy (e.g. Ropert-Coudert and Wilson 2005; Rutz and Hays 2009) in relation to atmospheric conditions. In addition to individual tracking, radar is an excellent tool for observing long-term spatial and temporal patterns of migration at specific locations and has been used for several decades in studies of the migration of birds (e.g. Erni et al. 2005; van Belle et al. 2007; Schmaljohann et al. 2009), bats (e.g. Kunz et al. 2008) and insects (e.g. Chapman et al. 2003; Reynolds et al. 2005;). Weather radar networks are particularly promising as they provide multiple stations and can potentially help study larger-scale patterns and trajectories more effectively then single locations. Although weather-surveillance Doppler radar has been used in the United States for such studies (e.g. Diehl et al. 2003; Gauthreaux et al. 2008; Westbrook 2008), only recently have several radars in the OPERA network in Europe (Operational Programme for the Exchange of Weather Radar Information; Kock et al. 2000) been successfully tested for studying bird migration (Holleman et al. 2008; van Gasteren et al. 2008; Doktor et al. in review) and it will become a valuable resource when studying Palearctic migration systems.

Atmospheric dynamics can affect migration systems at many different levels, from instantaneous changes in flight speed and direction to influencing breeding success. We hope to see meteorology more strongly integrated into future research on migration across multiple taxa. Such an interdisciplinary approach will help advance research on migration as well as address some of the grand challenges in organismal biology (Schwenk et al. 2009; Bowlin et al. this issue).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. Bowlin, I. A. Bisson and M. Wikelski for organizing, and inviting J.S.B. to give a talk at the Integrative Migration Biology symposium at the 2010 Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology meeting in Seattle, Washington. SICB’s Divisions of Animal Behavior, Neurobiology, and Comparative Endocrinology all donated money to the symposium. The authors thank J. Leyrer as well as two anonymous reviewers for discussions and constructive feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript. They thank M. Duyvendak, for retrieving articles we did not have direct access to. Our migration studies are facilitated by the BiG Grid infrastructure for eScience (http://www.biggrid.nl).

References

- Able KP. The role of weather variables and flight direction in determining the magnitude of nocturnal bird migration. Ecology. 1973;54:1031–41. [Google Scholar]

- Åkesson S, Hedenström A. Wind selectivity of migratory flight departures in birds. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2000;47:140–4. [Google Scholar]

- Åkesson S, Walinder G, Karlsson L, Ehnbom S. Nocturnal migratory flight initiation in reed warblers Acrocephalus scirpaceus: effect of wind on orientation and timing of migration. J Avian Biol. 2002;33:349–57. [Google Scholar]

- Allen MJ. Updraft Model for Development of Autonomous Soaring Uninhabited Air Vehicles. Forty Fourth AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; Reno, Nevada. 2006 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S, van Dinther M, Høgda K-A, Klaassen M, Madsen J. The consequences of climate-driven stop-over sites changes on migration schedules and fitness of Arctic geese. J Anim Ecol. 2008;77:654–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S, Barta Z, Ens BJ, Hays GC, McNamara JM, Klaassen M. Animal migration: linking models and data beyond taxonomic limits. Biol Lett. 2009;5:433–5. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bildstein KL. Migrating raptors of the world: their ecology and conservation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bildstein KL, Zalles JI. Old world versus new world long-distance migration in accipiters, buteos, and falcons. In: Greenberg R, Marra PP, editors. The interplay of migration ability and global biogeography. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. pp. 154–67. Birds of two worlds: the ecology and evolution of migration. Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlin M, et al. In press. Grand challenges in migration biology. Integr Comp Biol. doi: 10.1093/icb/icq013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes D, Ombalski DW. Modeling raptor migration pathways using a fluid-flow analogy. J Raptor Research. 2004;38:195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Brattström O, Kjellén N, Alerstam T, Åkesson S. Effects of wind and weather on red admiral, Vanessa atalanta, migration at a coastal site in southern Sweden. Anim Behav. 2008;76:335–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bruderer B, Underhill LG, Liechti F. Altitude choice by night migrants in a desert area predicted by meteorological factors. Ibis. 1995;137:44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Butler RW, Williams TD, Warnock N, Bishop M. Wind assistance a requirement for migration of shorebirds? Auk . 1997;114:456–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JW, Reynolds DR, Smith AD. Vertical-looking radar: a new tool for monitoring high-altitude insect migration. Bioscience. 2003;53:503–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JW, Nesbit RL, Burgin LE, Reynolds DR, Smith AD, Middleton DR, Hill JK. Flight orientation behaviors promote optimal migration trajectories in high-flying insects. Science. 2010;327:682–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1182990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JW, Reynolds DR, Mouritsen H, Hill JK, Riley JR, Sivell D, Smith AD, Woiwod IP. Wind selection and drift compensation optimize migratory pathways in a high-flying moth. Curr Biol. 2008;18:514–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan PM, Brown AC. Migration of bats past a remote island offers clues toward the problem of bat fatalities at wind turbines. Biol Conserv. 2007;139:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dänhardt J, Lindström Å. Optimal departure decisions of songbirds from an experimental stopover site and the significance of weather. Anim Behav. 2001;62:235–43. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl RH, Larkin RP, Black JE. Radar observations of bird migration over the Great Lakes. Auk. 2003;120:278–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dingle H. Migration: the biology of life on the move. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Drake VA, Farrow RA. The influence of atmospheric structure and motions on insect migration. Ann Rev Entomol. 1988;33:183–210. [Google Scholar]

- Erni B, Liechti F, Bruderer B. How does a first year passerine migrant find its way? Simulating migration mechanisms and behavioural adaptations. Oikos. 2003;103:333. [Google Scholar]

- Erni B, Liechti F, Bruderer B. The role of wind in passerine autumn migration between Europe and Africa. Behav Ecol. 2005;16:732–40. [Google Scholar]

- Erni B, Liechti F, Underhill LG, Bruderer B. Wind and rain govern the intensity of nocturnal bird migration in central Europe – a log-linear regression analysis. Ardea. 2002;90:155–66. [Google Scholar]

- Garland MS, Davis AK. An examination of Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) autumn migration in coastal Virginia. American Midland Naturalist. 2002;147:170–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthreaux SA, Jr, Livingston JW, Belser CG. Detection and discrimination of fauna in the aerosphere using Doppler weather surveillance radar. Integr Comp Biol. 2008;48:12–23. doi: 10.1093/icb/icn021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibo DL. Some observations on soaring flight in the Mourning Cloak Butterfly (Nymphalis antiopa L.) in southern Ontario. J New York Entomol S. 1981;89:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gibo DL, Pallett MJ. Soaring flight of monarch butterflies, Danaus plexippus (Lepidoptera: Danaidae), during late summer migration in southern Ontario. Can J Zool. 1979;57:1393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Gill RE, Tibbitts TL, Douglas DC, Handel CM, Mulcahy DM, Gottschalck JC, Warnock N, McCaffery BJ, Battley PF, Piersma T. Extreme endurance flights by landbirds crossing the Pacific Ocean: ecological corridor rather than barrier? Proc R Soc B. 2009;276:447–57. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grell G, Dudhia J, Stauffer D. NCAR Technical Note. NCAR; 1994. A description of the fifth-generation Penn State/NCAR Mesoscale Model (MM5) p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm V, et al. A standard protocol for describing individual-based and agent-based models. Ecol Model. 2006;198:115–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett TB, Coulson T, Pilkington JG, Clutton-Brock TH, Pemberton JM, Grenfell BT. Why large-scale climate indices seem to predict ecological processes better than local weather. Nature. 2004;430:71–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holleman I, van Gasteren H, Bouten W. Quality assessment of weather radar wind profiles during bird migration. J Atmospheric Oceanic Technol. 2008;25:2188–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hüppop O, Hüppop K. North Atlantic Oscillation and timing of spring migration in birds. Proc R Soc B. 2003;270:233–40. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell J, Kushnir Y, Ottersen G, Visbek M. An overview of North Atlantic Oscillation. In: Hurrell J, Kushnir Y, Ottersen G, visbek M, editors. The North Atlantic Oscillation: climate significance and environmental impacts. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union; 2003. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jonzen N, et al. Rapid advance of spring arrival dates in long-distance migratory birds. Science. 2006;312:1959–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1126119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalnay E, et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 1996;77:437–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlinger P. Flight strategies of migrating hawks. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kock K, Leitner T, Randeu WL, Divjak M, Schreiber KJ. First results and outlook for the future. Vol. 25. Phys Chem Earth B: Hydrol Oceans Atmosphere; 2000. OPERA: Operational Programme for the Exchange of Weather Radar Information; pp. 1147–51. [Google Scholar]

- Klok EJ, Klein Tank AMG. Updated and extended European dataset of daily climate observations. Int J Climatol. 2009;29:1182–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz TH, et al. Aeroecology: probing and modeling the aerosphere. Integr Comp Biol. 2008;48:1–11. doi: 10.1093/icb/icn037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshem Y, YomTov Y. The use of thermals by soaring migrants. Ibis. 1996a;138:667–74. [Google Scholar]

- Leshem Y, YomTov Y. The magnitude and timing of migration by soaring raptors, pelicans and storks over Israel. Ibis. 1996b;138:188–203. [Google Scholar]

- Leshem Y, YomTov Y. Routes of migrating soaring birds. Ibis. 1998;140:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Leskinen M, Markkula I, Koistinen J, Pylkkö P, Ooperi S, Siljamo P, Ojanen H, Raiskio S, Tiilikkala K. Pest insect immigration warning by an atmospheric dispersion model, weather radars and traps. J Appl Entomol. 2009 published online (doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2009.01480.x) [Google Scholar]

- Leyrer J, Bocher P, Robin F, Delaporte P, Goulevent C, Joyeux E, Meunier F, Piersma T. Northward migration of Afro-Siberian Knots Calidris canutus canutus: High variability in Red Knots numbers visiting stopover sites on French Atlantic coast (1979–2009) Wader Study Group Bull. 2009;116:145–51. [Google Scholar]

- Liechti F. Birds: blowin’ by the wind? J Ornithol. 2006;147:202–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel JT, Bildstein KL, Bohrer G, Winkler DW. Movement ecology of migration in turkey vultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19102–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801789105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan R, Getz WM, Revilla E, Holyoak M, Kadmon R, Saltz D, Smouse PE. A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19052–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800375105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan R, et al. Long-distance biological transport processes through the air: can nature's complexity be unfolded in silico? Divers Distrib. 2005;11:131–7. [Google Scholar]

- Newton I. Can conditions experienced during migration limit the population levels of birds? J Ornithol. 2006;147:146–66. [Google Scholar]

- Newton I. The migration ecology of birds. Oxford: Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pennycuick CJ, Alerstam T, Larsson B. Soaring migration of the common crane Grus grus observed by radar and from an aircraft. Ornis Scand. 1979;10:241–51. [Google Scholar]

- Piersma T, Lindström Å. Rapid reversible changes in organ size as a component of adaptive behaviour. Trends Ecol Evol. 1997;12:134–8. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(97)01003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piersma T, van de Sant S. Pattern and predictability of potential wind assistance for waders and geese migrating from West Africa and the Wadden Sea to Siberia. Ornis Svecica. 1992;2:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Piersma T, Prokosch P, Bredin D. The migration system of Afro-Siberian knots Calidris canutus canutus. Wader Study Group Bull. 1992;64(Suppl):52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly JR, Reilly RJ. Bet-hedging and the orientation of juvenile passerines in fall migration. J Anim Ecol. 2009;78:990–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds AM, Reynolds DR, Riley JR. Does a ‘turbophoretic’ effect account for layer concentrations of insects migrating in the stable night-time atmosphere? J R Soc Interface. 2009;6:87–95. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DR, Chapman JW, Edwards AS, Smith AD, Wood CR, Barlow JF, Woiwod IP. Radar studies of the vertical distribution of insects migrating over southern Britain: the influence of temperature inversions on nocturnal layer concentrations. B Entomol Res. 2005;95:259–74. doi: 10.1079/ber2004358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DS. Monitoring the potential impact of a wind development site on bats in the northeast. J Wildlife Manag. 2006;70:1219–27. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson WJ. Timing and amount of bird migration in relation to weather: a review. Oikos. 1978;30:224–72. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson WJ. Timing of bird migration in relation to weather: updated review. In: Gwinner E, editor. Bird migration. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 78–101. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson WD, Bowlin MS, Bisson I-A, Shamoun-Baranes J, Thorup K, Diehl RH, Kunz TH, Mabey S, Winkler DW. Integrating concepts and technologies to advance the study of bird migration. Front Ecol Environ. In press [Google Scholar]

- Ropert-Coudert Y, Wilson RP. Trends and perspectives in animal-attached remote sensing. Front Ecol Environ. 2005;3:437–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rutz C, Hays GC. New frontiers in biologging science. Biol Lett. 2009;5:289–92. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir N. The effect of weather on Bee-eater (Merops apiaster) migration. Jerusalem: Hebrew University. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Schaub M, Liechti F, Jenni L. Departure of migrating European robins, Erithacus rubecula, from a stopover site in relation to wind and rain. Anim Behav. 2004;67:229–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schmaljohann H, Liechti F, Bruderer B. Trans-Sahara migrants select flight altitudes to minimize energy costs rather than water loss. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2009;63:1609–19. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk K, Padilla DK, Bakken GS, Full RJ. Grand challenges in organismal biology. Integr Comp Biol. 2009;49:7–14. doi: 10.1093/icb/icp034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RW, Achtemeier GL. Estimating pathways of migrating insects carried in atmospheric winds. Environ Entomol. 1987;16:1244–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shamoun-Baranes J, Leshem Y, Yom-Tov Y, Liechti O. Differential use of thermal convection by soaring birds over central Israel. Condor. 2003b;105:208–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shamoun-Baranes J, Liechti O, Yom-Tov Y, Leshem Y. Using a convection model to predict altitudes of white stork migration over central Israel. Bound-Lay Meteorol. 2003c;107:673–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shamoun-Baranes J, van Loon E, Alon D, Alpert P, Yom-Tov Y, Leshem Y. Is there a connection between weather at departure sites, onset of migration and timing of soaring-bird autumn migration in Israel? Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2006;15:541–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shamoun-Baranes J, Baharad A, Alpert P, Berthold P, YomTov Y, Dvir Y, Leshem Y. The effect of wind, season and latitude on the migration speed of white storks Ciconia ciconia, along the eastern migration route. J Avian Biol. 2003a;34:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shamoun-Baranes J, Leyrer J, van Loon E, Bocher P, Robin F, Meunier F, Piersma T. Stochastic atmospheric assistance and the use of emergency staging sites by migrants. Proc R Soc B. 2010 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.2112. published online (doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.2112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon HD, Young GS, Yates MA, Fuller MR, Seegar WS. American White Pelican soaring flight times and altitudes relative to changes in thermal depth and intensity. Condor. 2002a;104:679–83. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon HD, Young GS, Yates MA, Fuller MR, Seegar WS. Measurements of thermal updraft intensity over complex terrain using American White Pelicans and a simple boundary-layer forecast model. Bound-Lay Meteorol. 2002b;104:167–99. [Google Scholar]

- Spaar R, Bruderer B. Migration by flapping or soaring: Flight strategies of Marsh, Montagu's and Pallid Harriers in southern Israel. Condor. 1997;99:458–69. [Google Scholar]

- Spaar R, Stark H, Liechti F. Migratory flight strategies of Levant sparrowhawks: time or energy minimization? Anim Behav. 1998;56:1185–1197. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1998.0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srygley RB, Dudley R. Optimal strategies for insects migrating in the flight boundary layer: mechanisms and consequences. Integr Comp Biol. 2008;48:119–33. doi: 10.1093/icb/icn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanescu C, Alarcón M, Àvila A. Migration of the painted lady butterfly, Vanessa cardui, to north-eastern Spain is aided by African wind currents. J Anim Ecol. 2007;76:888–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöcker S, Weihs D. Bird migration – an energy-based analysis of costs and benefits. IMA J Math Appl Med. 1998;15:65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard PK, Marsden JE, Williams TC. Computer simulation of autumnal bird migration over the western North Atlantic. Anim Behav. 1983;31:173–80. [Google Scholar]

- Stutchbury BJM, Tarof SA, Done T, Gow E, Kramer PM, Tautin J, Fox JW, Afanasyev V. Tracking long-distance songbird migration by using geolocators. Science. 2009;323:896. doi: 10.1126/science.1166664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor IJ, Deelman E, Gannon DB, Shields M, editors . Workflows for e-Science. London: Springer-Verlag; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thorup K, Alerstam T, Hake M, Kjellen N. Bird orientation: compensation for wind drift in migrating raptors is age dependent. Biol Lett. 2003;270:8–11. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Belle J, Shamoun-Baranes J, van Loon E, Bouten W. An operational model predicting autumn bird migration intensities for flight safety. J Appl Ecol. 2007;44:864–74. [Google Scholar]

- van de Kam J, Ens B, Piersma T, Zwarts L. Shorebirds: an illustrated behavioural ecology. Utrecht: KNNV Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- van Gasteren H, Holleman I, Bouten W, Van Loon E, Shamoun-Baranes J. Extracting bird migration information from C-band Doppler weather radars. Ibis. 2008;150:674–86. [Google Scholar]

- Vrugt JA, van Belle J, Bouten W. Pareto front analysis of flight time and energy use in long-distance bird migration. J Avian Biol. 2007;38:432–42. [Google Scholar]

- Weber TP, Alerstam T, Hedenström A. Stopover decisions under wind influence. J Avian Biol. 1998;29:552–60. [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook JK. Noctuid migration in Texas within the nocturnal aeroecological boundary layer. Integr Comp Biol. 2008;48:99–106. doi: 10.1093/icb/icn040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikelski M, Kays RW, Kasdin NJ, Thorup K, Smith JA, Swenson GW., Jr Going wild: what a global small-animal tracking system could do for experimental biologists. J Exp Biol. 2007;210:181–6. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikelski M, Moskowitz D, Adelman JS, Cochran J, Wilcove DS, May ML. Simple rules guide dragonfly migration. Biol Lett. 2006;2:325–9. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood CR, Chapman JW, Reynolds DR, Barlow JF, Smith AD, Woiwod IP. The influence of the atmospheric boundary layer on nocturnal layers of noctuids and other moths migrating over southern Britain. Int J Biometeorol. 2006;50:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s00484-005-0014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood CR, Clark SJ, Barlow JF, Chapman JW. Layers of nocturnal insect migrants at high-altitude: the influence of atmospheric conditions on their formation. Agric For Entomol. 2010;12:113–21. [Google Scholar]