Abstract

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder caused by an expanded polyglutamine repeat within the N-terminus of the huntingtin protein. It is characterized by a selective loss of medium spiny neurons in the striatum. It has been suggested that impaired proteasome function and ER stress play important roles in mutant huntingtin (mHtt) induced cell death. However, the molecular link involved is poorly understood. In the present study, we identified the essential role of the extra long form of Bim (Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death), BimEL, in mHtt-induced cell death. BimEL protein expression level was significantly increased in cell lines expressing the N-terminus of mHtt and in a mouse model of HD. Although quantitative RT-PCR analysis indicated that BimEL mRNA was increased in cells expressing mHtt, we provided evidence showing that, at the post-translational level, phosphorylation of BimEL played a more important role in regulating BimEL expression. Up-regulation of BimEL facilitated the translocation of Bax to the mitochondrial membrane, which further led to cytochrome c release and cell death. On the other hand, knocking down BimEL expression prevented mHtt-induced cell death. Taken together, these findings suggest that BimEL is a key element in regulating mHtt-induced cell death. A model depicting the role of BimEL in linking mHtt-induced ER stress and proteasome dysfunction to cell death is proposed.

Keywords: Huntington’s disease, BimEL, protein degradation, ubiquitin-proteasome system, phosphorylation

Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an inherited neurological disorder caused by an expanded polyglutamine (polyQ) repeat within the N-terminus of the huntingtin protein (Htt). It is characterized by a selective loss of medium spiny neurons in the striatum. In HD, polyQ fragments derived from the N-terminus of mutant Htt (mHtt) have been shown to form nuclear or perinuclear aggregations in HD patients (DiFiglia et al., 1997) and in different cell types (Krobitsch & Lindquist, 2000; Li et al., 2000a; Nishitoh et al., 2002). mHtt aggregates inhibit the activity of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), due to the fact that it can sequester ubiquitin, an essential component of the UPS (de Pril et al., 2004). In addition, Htt aggregates also trigger ER stress. It has been suggested that impaired proteasome function and ER stress play important roles in mHtt-induced cell death (Jana et al., 2001). However, the molecular link involved is poorly understood.

Bim (Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death) belongs to a subgroup of pro-apoptotic proteins that only resemble other Bcl-2 family members within the short BH3 domain (Ley et al., 2005). Bim has three major isoforms: Bim short (BimS), Bim long (BimL) and Bim extra long (BimEL), which are generated by alternative splicing. They have different pro-apoptotic potencies with BimS being the most effective killer and BimEL being the least effective killer (Ley et al., 2005). However, BimEL is the most abundant form and is widely expressed in hematopoietic, epithelial, neuronal and germ cells (O’Reilly et al., 2000). BimEL is expressed at a low level in healthy cells but is greatly up-regulated in apoptotic cells.

BimEL expression is regulated at both transcriptional and post-translational levels. Several transcription factors are involved in regulating BimEL transcription. Forkhead box, class O (FOXO) transcription factor, FKHRL1 (FOXO3a), was found to directly activate bim promoter via two conserved FOXO binding sites and promote apoptosis in sympathetic neurons after nerve growth factor withdrawal (Gilley et al., 2003). In another report, it was suggested that GADD153 (growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 153) and C/EBP heterodimers bind to a site within the first intron of the bim gene to increase its transcription during ER stress (Puthalakath et al., 2007). At the post-translational level, BimEL is phosphorylated by extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK). Phosphorylation of BimEL by ERK1/2 promotes its degradation via the proteasome pathway and thus antagonizes its pro-apoptotic activity (Luciano et al., 2003; Ley et al., 2004). On the other hand, phosphorylation of BimEL by JNK potentiates its pro-apoptotic activity (Lei & Davis, 2003; Becker et al., 2004).

BimEL is critical for neuronal apoptosis induced by nerve growth factor deprivation (Putcha et al., 2001). More recently, it has been shown that ER stress requires BimEL for initiating apoptosis in diverse range of cell types (Puthalakath et al., 2007). In the present study, we present evidence showing that BimEL is up-regulated as a result of impaired UPS function in response to mHtt and up-regulation of BimEL plays an important role in mHtt-induced cell death.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, plasmid and transfection

Plasmid cDNA encoding the N-terminal region of human Htt (1-69) with polyQ repeat length of 25Q (Addgene plasmid 1187), 72Q (Addgene plasmid 1183) and 103Q (Addgene plasmid 1186) fused to EGFP were obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA) (Krobitsch & Lindquist, 2000). They were subcloned into a mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1/HisB (Invitrogen, CA) and designated as pcDNA3.1/HisB-Htt25Q, pcDNA3.1/HisB-Htt72Q and pcDNA3.1/HisB-Htt103Q, respectively. Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells and Neuro-2a cells (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) were cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mM MEM non-essential amino acid (NEAA), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1 mM MEM sodium pyruvate. HEK293 cells or Neuro-2a cells were transiently transfected with the above plasmid constructs using the standard lipofectamine LTX method according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Unless stated elsewhere, the cells were harvested 48 hours after transfection.

Animals, genotyping and sample preparation

Breeding pairs of R6/2 transgenic mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), and the line was maintained by backcrossing to CBA3 C57BL/6 F1 in the animal facilities of Florida Atlantic University (FAU). All animals were maintained under temperature-and light- controlled conditions (20–23°C, 12-hour-light/12-hour-dark cycle) with continuous access to food and water. Primer sequences used for genotyping were: 5′-ATG AAG GCC TTC GAG TCC CTC AAG TCC TTC -3′ and 5′-GGC GGC TGA GGA AGC TGA GGA -3′. PCR program was: 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec; 58°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 1.5 min; 72°C for 10 min as the final elongation step. The PCR product was run on a 2% agarose gel. A single band at ~524 bp indicated the hemizygous type. Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of FAU.

For sample preparation, 13-week-old R6 2 mice and their control littermates were rapidly euthanized under halothane anesthesia and the brains were quickly removed. striatum was then dissected and lysed in lysis buffer at 4°C for 30 min (50mM Tris, pH=7.5, 5mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail). After lysis, the samples were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to remove any insoluble materials. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

RNA was isolated using MasterPure™ RNA purification kit as instructed by the manufacturer (Epicentre, WI, USA). First-strand cDNA was prepared with Protoscript® II RT-PCR kit (New England Biolabs, MA, USA). The amounts of BimEL transcripts in cells transfected with different polyQ constructs were analyzed by quantitative PCR using the SYBR green method (Stratagene, CA, USA). The samples were analyzed in triplicates using the Mx3005P™ Real-Time PCR System and compared using EGFP as a normalizer gene. Fold increase was calculated using the relative Ct method. The forward and reverse primers used for human BimEL (NM_138621) were: 5 ′-TCCCTGCTGTCTCGATCCTC-3 ′ and 5 ′-GGTCTTCGGCTGCTTGGTAA-3′ respectively. The forward and reverse primers used for EGFP were: 5′-ACAACTACAACAGCCACAAC-3′ and 5′-GACTGGGTGCTCAGGTAG-3′ respectively.

Proteasome activity assay

Proteasome activity assay was performed as described with minor modifications (Wang et al., 2008). Cell pastes were homogenized in homogenization buffer (15 mM Tris-HCl, pH=8.0, 60 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA and 2 mM ATP) at 4°C. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,300 × g for 10 min to remove unbroken tissues and nuclei fractions. Protein concentration was measured and adjusted to 0.5 mg/ml total protein by dilution with homogenization buffer. All assays were done in triplicate. Chymotrypsin-like activity of 20S proteasome was determined using substrate Suc-LLVY-aminomethycoumarin (AMC) (50 μM, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Caspase-like activity was measured using Z-LLE-AMC (50 μM, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Trypsin-like activity was measured using Z-ARR-AMC (50 μM, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). 10 μg of cell lysate was incubated with each of the substrate in 100μl proteasome activity assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH=8.0, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1mM ATP, 1mM DTT) for 30 min at 37°C. The reactions were stopped by addition of 100 μl of stop solution (2% SDS). Released fluorogenic AMC was measured at 360 nm excitation and 460 nm emission in a microplate luminometer (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). Fluorescence units were converted to AMC concentration using standard curves generated from free AMC.

MG-132 treatment

MG-132, a proteasome inhibitor, was purchased from Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ, USA) and dissolved in DMSO. HEK293 cells or N2a cells were incubated with different concentration of MG-132 (1 μM and 20 μM) for 4 hours before harvest. 1% DMSO was used in the control group to account for the 1% DMSO introduced by the MG-132 treatment.

Immunofluorescence

Forty-eight hours after transfection, HEK293 cells grown on coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min at room temperature. After fixation, 4% PFA was removed and 1 ml cold methanol stored at −20°C was added and incubated for 1 min to permeablize the membrane. Cells were first blocked in blocking buffer (1% normal goat serum, 1% BSA in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature followed by incubation with GADD153 antibodies (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. For fluorescent visualization, cells were incubated with the secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa 594 (1:2000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Between steps, cells were washed 3 times for 10 min in PBS. Cells were then mounted on a slide using Prolong® Gold antifade Reagent (Invitrogen) and observed under an Olympus AX70 fluorescent microscope.

Mitochondria preparation

The mitochondria fraction was prepared using a well-established procedure as described (Biagioli et al., 2008). Briefly, cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice in ice-cold PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in five volumes of resuspension buffer (20 mM HEPES–KOH, pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM sodium EDTA, 1 mM sodium EGTA, 1 mM dithioerytrol, 250 mM sucrose, 1X complete protease inhibitor cocktail, 1X phosphatase inhibitor cocktail) and homogenized followed by centrifugation at 750 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged again at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. The resulting mitochondria pellet was washed twice with cold PBS and dissolved in an appropriate volume of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH=7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton-X-100, 1X complete protease inhibitor cocktail, 1X phosphatase inhibitor cocktail) and the supernatant was collected to get the cytosolic fraction. Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were used for immunoblotting analysis.

Immunoblotting analysis

After transfection, cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice in cold PBS. The cell pellet was then lysed in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris, pH=7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1X complete protease inhibitor cocktail from Sigma, 1X phosphatase inhibitor cocktail from Pierce). Whole cell lysates (20–50μg), brain striatal lysate (20–50 μg) or mitochondrial extracts (~20μg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked with blocking buffer for 2 hours at room temperature. The membrane was then incubated with different antibodies against BimEL (1:500), phospho-BimEL (Ser69) (1:500); JNK (1:500), phospho-JNK (1:500), ERK (1:500), phospho-ERK (1:500), cleaved caspase-3 (1:500), PARP (1:500), cytochrome c (1:500), GADPH (1:1000), Bid (1:500, mouse specific) and Puma (1:500, the above antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), GADD153 (1:200), GFP (1:1000), COX IV (1:500, the above antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or Bax (1:500, Chemicon, Billerica, MA, USA) followed by incubating with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies. Signals were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence and analyzed with NIH image J.

siRNA transfection

Mouse BimEL ON-TARGET PLUS SMARTpool siRNA was obtained from Dharmacon (Chicago, IL, USA). Bim siRNA duplex and different Htt plasmid constructs were co-transfected into Neuro-2a cells using lipofectamine LTX method according to the manufacturer’s instruction. A FITC-conjugated fluorescent oligo (Invitrogen, CA, USA) was used to monitor the transfection efficiency. A transfection efficiency of ~90% was routinely obtained.

ATP assay

Cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at 1 × 105 cells/well and transfected with different Htt plasmids in the presence or absence of BimEL siRNA duplex using lipofectamine LTX method. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were trypsinized and counted using a hemocytometer. Cells were further diluted into 1 × 104 cells/ml using culture medium and 100 μl of cells were transferred to a well in a 96-well plate. ATP content was measured in accordance with the protocol of the CellTiter-Glo™ luminescent cell viability assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Briefly, 100μl of assay reagent was added to the wells and mixed for 2 min followed by further incubation for 10 min at room temperature. ATP content was measured using a microplate luminometer (Molecular Devices, CA, USA). The background luminescence of the culture medium was subtracted.

Trypan blue exclusion assay

Cell viability was also determined using the trypan blue exclusion assay. Briefly, Forty-eight hours after transfection with Htt plasmids in the presence or absence of BimEL SiRNA, Neuro-2a cells were trypsinized and resuspended in Neuro-2a media. Ten microliters of the cell suspension was diluted (1:2) using 4% trypan blue solution (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA). Trypan blue stains only non-viable cells leaving viable cells clear. Ten microliters of the diluted suspension was loaded to a hemocytometer and observed under a light microscope. The number of stained (dead) cells and unstained (live) cells was counted. The percentage of dead cells in each group was calculated by dividing the number of dead cells by the total number of cells present.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as means ± S.E.M. To establish significance, data were subjected to unpaired student’s t-tests using the GraphPad Prism software statistical package (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The criterion for significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

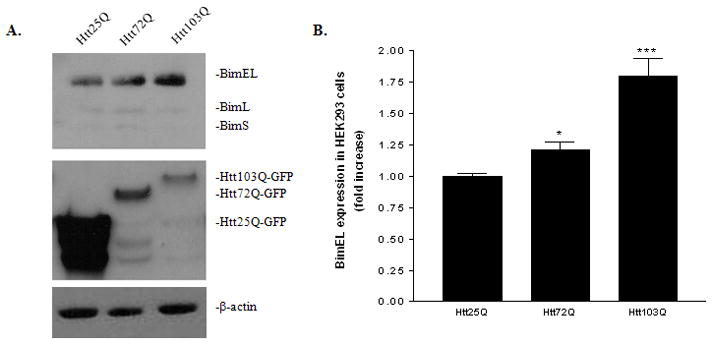

Up-regulation of BimEL expression in response to mHtt expression in HEK293 cells

BimEL has been shown to play an important role in ER stress induced apoptosis in a diversity of cell types (Puthalakath et al., 2007) and is critical for neuronal apoptosis (Putcha et al., 2001). We first investigated whether mHtt expression in HEK293 cells would induce an increase in BimEL expression by western blot. Although HEK293 cells are not neuronal cells, it has been extensively used in HD studies (Cornett et al., 2005; Iwata et al., 2005). As shown in Fig. 1A, a gradual increase of BimEL expression was observed in HEK293 cells expressing Htt72Q-EGFP and Htt103Q-EGFP compared with those cells expressing Htt25Q-EGFP (top panel). EGFP antibodies were used to detect the expression of Htt. Cells transfected with Htt103Q-EGFP showed much lower expression of Htt than those cells transfected with Htt25Q-EGFP (Fig. 1A, middle panel). The transfect efficiencies among these plasmids are similar as revealed by a fluorescent microscope (~80–90% transfect efficiency). Therefore, it is likely due to the fact that Htt103Q easily forms aggregates which could be partially insoluble in our preparations as reported (King et al., 2008). BimEL expression was quantified with densitometry over β-actin expression. Htt103Q-EGFP expression in HEK293 cells caused a significant increase in BimEL protein level by ~75% (Fig. 1B, t-test, P = 0.0006, n = 5). Htt72Q expression also led to a 25% increase in BimEL expression (Fig. 1B, t-test, P = 0.03, n = 5), indicating that increase of BimEL expression correlates with the length of polyQ.

Figure 1.

Up-regulation of BimEL in response to mHtt expression in HEK293 cells. A, Immunoblotting analysis of BimEL expression in HEK293 expressing Htt25Q, Htt72Q or Htt103Q. Total cell lysates were probed with antibodies against Bim or EGFP which is fused to the C-terminus of the Htt.β-actin was used as a loading control. B, Quantitative analysis of BimEL expression. BimEL protein expression level from five independent immunoblottings was quantified with densitometry and normalized with β-actin expression. *p<0.05; ***p<0.001 as compared with cells expressing Htt25Q, n=5.

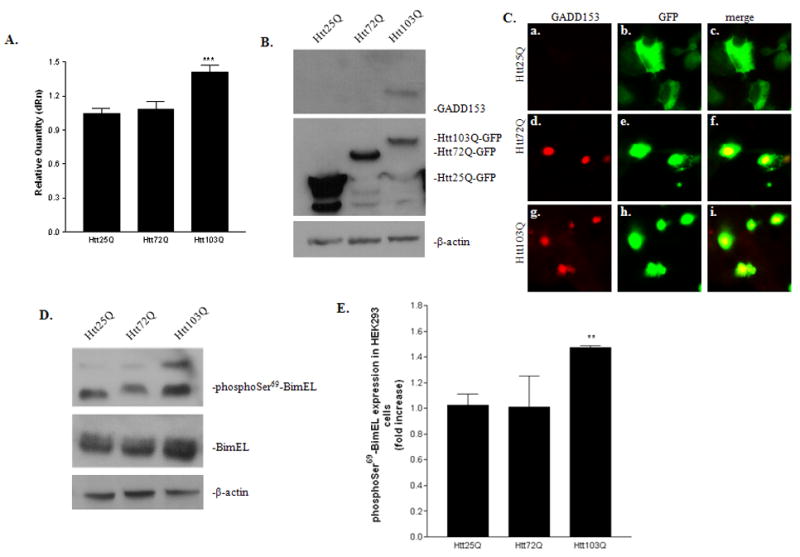

Regulation of BimEL at transcriptional and post-translational levels in HEK293 cells

We next investigated whether the up-regulation of BimEL expression is due to an increase in BimEL mRNA. The level of BimEL mRNA in different samples was quantified using quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 2A, Htt103Q-EGFP expression increased BimEL mRNA by ~40% (Fig. 2A, t-test, P = 0.0002, n = 8). Although transfection of Htt72Q also caused a slight increase in BimEL mRNA expression, statistical analysis revealed that it was not significant (Fig. 2A, t-test, P = 0.67, n = 8). GADD153 and C/EBP heterodimers have been shown to bind to a site within the first intron of the bim gene to increase its transcription during ER stress (Puthalakath et al., 2007). We therefore examined whether mHtt expression triggered ER stress and induced GADD153 expression. Overexpression of Htt103Q led to a significant increase in GADD153 protein expression as shown by western blot (Fig. 2B). Immunofluorescent staining of the transfected cells also showed that GADD153 expression was greatly increased in cells expressing mHtt (Fig. 2C). The presence of EGFP at the end of the N-terminal region of Htt allowed us to follow its subcellular localization and aggregation formation. Consistent with most reported studies, expression of Htt103Q-EGFP formed nuclear or perinuclear aggregates as shown by intense fluorescent signals, while cells expressing Htt25Q-GFP showed diffuse EGFP signal in the cell body (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Regulation of BimEL at transcriptional and post-translational levels in HEK293 cells. A, Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of BimEL mRNA expression. BimEL mRNA expression from different samples were analyzed using EGFP as a normalizer gene and the relative quantity was compared with cells expressing Htt25Q. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p<0.001 as compared with cells expressing Htt25Q, two-tailed unpaired t-test. n=8 for Htt25Q and n=8 for Htt103Q. B, Up-regulation of GADD153, an ER stress marker, in cells expressing Htt103Q. Total cell lysates were probed with antibodies against GADD153, EGFP and β-actin. C, Detection of GADD153 expression by immunofluorescent staining. Cells were labeled with anti-GADD153 and observed under a fluorescent microscopy. D, Up-regulation of phospho-BimEL in cells expressing Htt103Q. The expression of BimEL or phosphorylated BimEL at Ser69 was analyzed by immunoblotting using a specific phospho-antibody against Bim or phophoSer69-BimEL. E, Quantitative analysis of phospho-BimEL expression. PhosphoSer69-BimEL protein expression level from three independent immunoblottings was quantified with densitometry and normalized with β-actin expression. **p<0.01 as compared with cells expressing Htt25Q, n=3.

BimEL expression is also regulated through protein phosphorylation (Luciano et al., 2003; Ley et al., 2004; Ley et al., 2005). Therefore, we next examined whether there were any changes in the status of BimEL phosphorylation. Treatment of the cell lysate with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP) resulted in a mobility shift of BimEL to a lower single band, indicating that BimEL was phosphorylated (data not shown). We then used a specific phospho-antibody against phosphorylated Ser69 of BimEL (phophoSer69-BimEL) to detect the endogenous level of phospho-BimEL. The level of phophoSer69-BimEL was also increased in cells expressing Htt103Q (Fig. 2D). Statistical analysis indicated an increase of 40% in phophoSer69-BimEL expression in Htt103Q cells compared to Htt25Q cells (Fig. 2E, t-test, P = 0.0056, n = 3). Interestingly, we also noticed that there was a mobility shift with phophoSer69-BimEL in cells expressing Htt72Q and Htt103Q, compared with cells expressing Htt25Q, indicating that some other sites were also phosphorylated in addition to Ser69 (Fig. 2D).

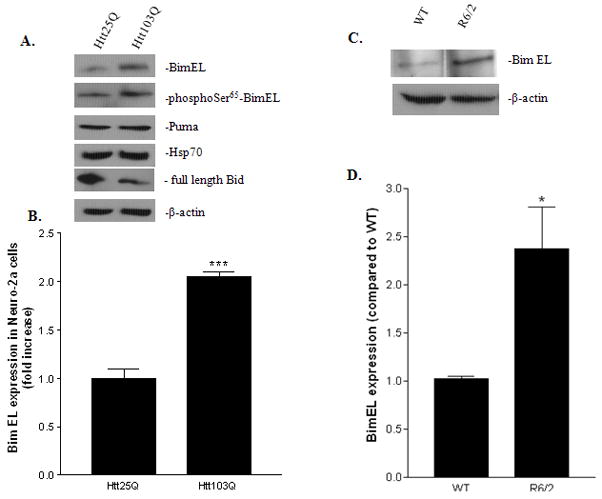

Up-regulation of BimEL expression in response to mHtt expression in Neuro-2a cells and a mouse model of HD

Since HD is a neurological disorder, we further tested our hypothesis in a neuronal cell line, neuro-2a (N2a). As shown in Fig. 3A, BimEL and phophoSer65-BimEL (Ser65 in rodent BimEL and Ser69 in human BimEL) expression were significantly increased in cells expressing Htt103Q compared with cells expressing Htt25Q. To check whether mHtt expression also affects the expression level of other BH3-only protein, we re-probed the membrane with antibodies against Puma. Puma expression was not changed in the two different groups of cells (Fig. 3A). The expression of another BH3-only protein, Bid, was shown to be elevated in two mouse models of HD (Zhang et al., 2003; Garcia-Martinez et al., 2007). We therefore tested the expression of Bid in our system. Interestingly, we detected a decrease in full length Bid in Htt103Q (Fig. 3A). Full length Bid can be cleaved into truncated Bid by caspase-8 which further induce apoptosis (Li et al., 1998; Luo et al., 1998). Since the antibody we used only detects full length Bid, we reasoned that full length Bid is cleaved into truncated Bid in cells expressing Htt103Q. In addition, Hsp70 has been shown to function as molecular chaperones to help restore cellular homeostasis (Krobitsch & Lindquist, 2000). However, we did not detect any significant changes in Hsp70 expression in our study (Fig. 3A). Densitometry analysis revealed that there is nearly a two-fold increase in BimEL expression in cells expressing Htt103Q compared with cells expressing Htt25Q (Fig. 3B, t-test, P = 0.0007, n = 3). We next examined the expression of BimEL in the striatum of 13-week-old R6/2 mice, a mouse model of HD. Compared with age-matched wild type animals, BimEL expression was significantly higher in R6/2 mice (Fig. 3C–3D, t-test, P = 0.04, n = 3).

Figure 3.

Up-regulation of BimEL expressing in response to mHtt in N2a cells and R6/2 mice. A, Immunoblotting analysis of BimEL expression in N2a cells expressing Htt25Q, or Htt103Q. Total cell lysates were probed with antibodies against BimEL, phosphoSer65-BimEL, Puma, Hsp70, full length Bid or β-actin. B, Quantitative analysis of BimEL expression. BimEL protein expression level from three independent immunoblottings was quantified with densitometry and normalized with β-actin expression. ***p<0.001 as compared with cells expressing Htt25Q, n=3. C, Immunoblotting analysis of BimEL expression in 13 weeks old R6/2 mice. Total striatal lysates from wild type or R6/2 mice were probed with antibodies against BimEL or β-actin. D, Quantitative analysis of BimEL expression in R6/2 mice. BimEL protein expression level from three independent immunoblottings was quantified with densitometry and normalized with β-actin expression. *p<0.05 as compared with the wild type group, n=3.

Our data suggest that BimEL is significantly increased in different cell lines that express mHtt and R6/2 mice. In the following studies, we used N2a cell lines to further investigate the role of BimEL in the pathogenesis of HD.

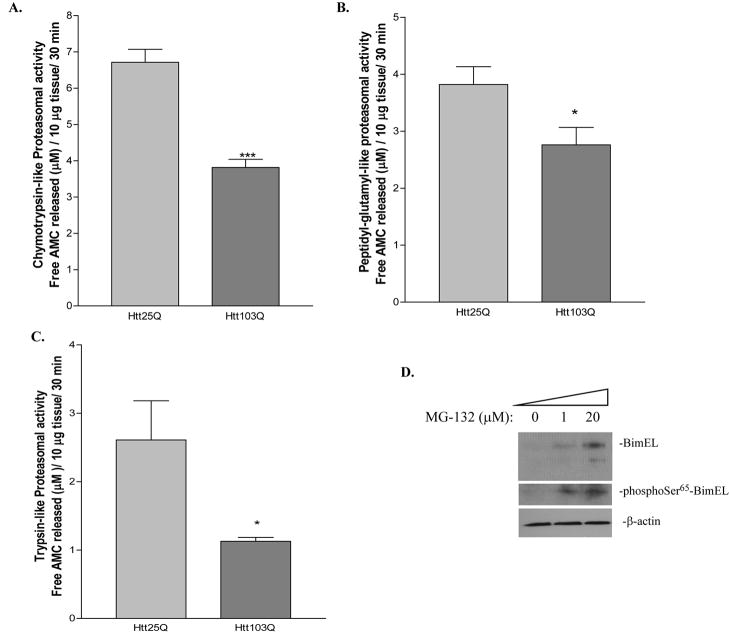

Impaired proteasome activity in N2a cells expressing mHtt

Phosphorylation of BimEL at Ser65 has been reported to target BimEL for proteasome degradation (Luciano et al., 2003; Ley et al., 2004). However, we observed an increase of BimEL and phophoSer65-BimEL in cells expressing Htt103Q (Fig. 2D, 3A). To explain this discrepancy, we hypothesize that proteasome activity in Htt103Q-expressed cells was impaired and thus could not degrade phophoSer65-BimEL. To test this hypothesis, we first assayed the chymotrypsin-, peptidyl-glutamyl- and trypsin-like proteasome activity using three different luminogenic proteasome substrates. As shown in Fig. 4A, the chymotrypsin-like activity was significantly reduced by 50% in N2a cells expressing Htt103Q compared with cells expressing Htt25Q (Fig. 4A, t-test, P = 0.0001, n = 5). Similarly, the peptidyl-glutamyl- and trypsin-like activities were also decreased in N2a cells expressing Htt103Q (Fig. 4B and C, t-test, peptidyl-glutamyl-like: P = 0.048, n = 4 for Htt25Q and n = 5 for Htt103Q; trypsin-like: P = 0.027, n = 6;).

Figure 4.

Impairment of proteasome activity in N2a cells expressing Htt103Q. A, Chymotrypsin-, B, Peptidyl-glutamyl- and C, Trypsin-like proteasome activity in N2a cells expressing Htt25Q or Htt103Q. The data are represented as free AMC (μM) released from 10 μg cell lysate in 30 minutes (mean ± SEM). *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 as compared with cells expressing Htt25Q. D, Accumulation of BimEL and phophoSer65-BimEL in MG-132 treated cells. N2a cells were treated with increasing concentrations of MG-132 as indicated for 4 hours. Changes in BimEL and phophoSer65-BimEL levels were analyzed by immunoblotting.

To further confirm that impaired proteasome activity results in increased expression of phophoSer65-BimEL and BimEL, we investigated whether MG-132, a proteasome inhibitor, is sufficient to promote the phosphorylation and accumulation of BimEL. N2a cells were treated with increasing concentrations of MG-132 for 4 hours. As expected, BimEL and phophoSer65-BimEL were increased in a concentration-dependent manner as revealed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4D).

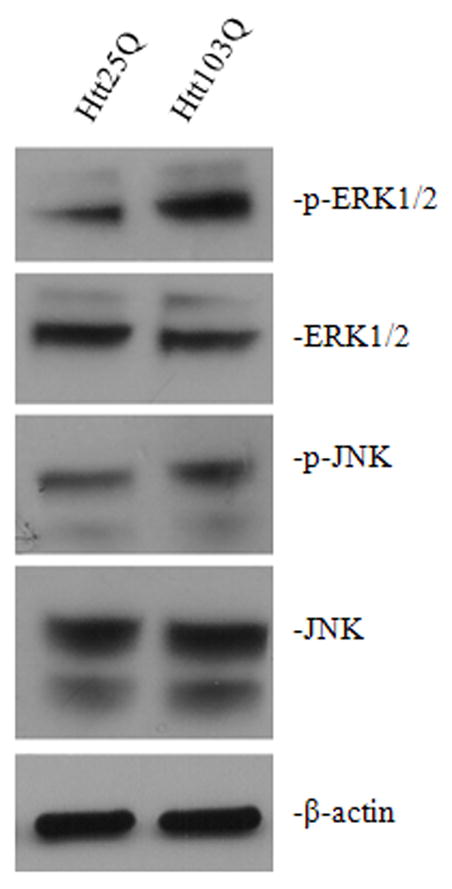

Activation of JNK and/or ERK in N2a cells expressing mHtt

We next investigated the kinases that are responsible for phosphorylating BimEL. To date, two major protein kinases have been identified to phosphorylate BimEL: ERK1/2 and JNK (Lei & Davis, 2003; Luciano et al., 2003). We therefore focused on these two kinases. N2a cells were transfected with Htt25Q or Htt103Q plasmids and harvested 48 hours later. The activation of ERK1/2 or JNK was determined by western blot using antibodies against phospho-ERK1/2 or phospho-JNK. As shown in Fig. 5, both ERK1/2 and JNK are activated in cells expressing Htt103Q. Total ERK1/2 or JNK expression was determined with anti-pan-ERK1/2 or anti-pan-JNK antibodies. No significant changes in the total ERK1/2 and JNK expression were noticed (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Activation of ERK1/2 and JNK activity. Forty-eight hours after transfection, N2a cells were harvested and analyzed by immunoblotting. Total cell lysates were probed with antibodies against p-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) and p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) to assay the level of activated ERK1/2 and JNK respectively, antibodies against ERK1/2 and JNK to determine the total level of ERK1/2 and JNK expression.

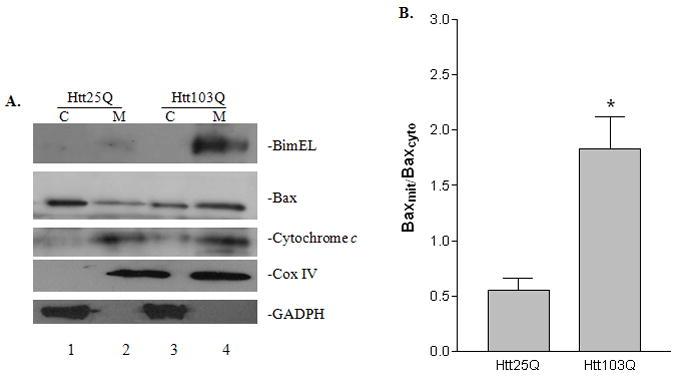

Effect of BimEL on the translocation of Bax to the mitochondrial membrane

We further investigated the downstream target of BimEL up-regulation. BimEL has been shown to facilitate the translocation of Bax to the mitochondrial membrane which leads to cytochrome c release and apoptosis (Putcha et al., 2003). We first showed that BimEL expression was increased in mitochondrial fraction of cells expressing Htt103Q (Fig. 6A). Moreover, Htt103Q expression clearly induced a translocation of Bax to the mitochondrial membrane (Fig. 6A, lane 4 vs. lane 2). We performed a quantitative analysis of the translocation of Bax from cytosol to mitochondria. As shown in Fig. 6B, there was a significant increase in mitochondrial Bax in cells expressing Htt103Q (t-test, P = 0.0144, n = 3). In addition, we also assayed the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to cytosol. As shown Fig 6A, more cytochrome c was released from mitochondria into cytosol in cells expressing Htt103Q (lane 3 vs. lane 1). The purity and enrichment of mitochondrial fractions were verified by the presence of cytochrome c oxidase complex IV (COX IV), a specific mitochondrial marker, and the absence of GADPH, a cytosolic marker (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Effect of BimEL on the translocation of Bax to the mitochondrial membrane and cytochrome c release. Forty-eight hours after transfection, N2a cells were harvested and separated into cytosolic (cyto) and mitochondrial (mito) fractions. A, The samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against Bim, Bax, cytochrome c, COXIV and GADPH as indicated. B, Quantitative analysis of Bax translocation from cytosolic to mitochondrial fraction by densitometry. *p<0.05 as compared with cells expressing Htt25Q, n=3.

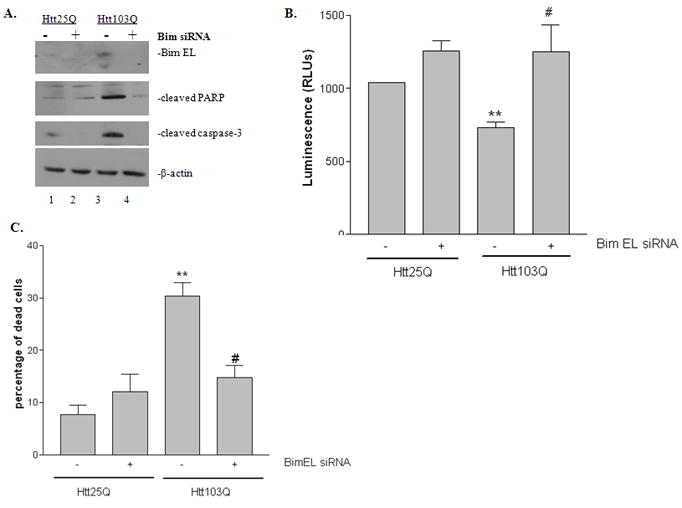

Effect of silencing BimEL on mHtt-induced cell death

To addressed whether BimEL is important for mHtt-induced cell death, we co-transfected Htt plasmids and mouse BimEL on-target plus SMARTpool siRNA into N2a cells. First, the silencing of BimEL was confirmed with western blot using BimEL antibodies (Fig. 7A). We then analyzed the expression of apoptotic-related proteins by immunoblotting. During apoptosis, poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) is effectively cleaved from its native 113-kDa form to an 89-kDa fragment. Therefore, the cleavage pattern of PARP is used as an indication of apoptosis progression (Oliver et al., 1998; Mullen, 2004). PARP cleavage was detected by immunoblotting using a specific antibody against PARP. As shown in Fig. 7A, cells expressing Htt103Q (lane 3) had more PARP cleavage compared with cells expressing Htt25Q (lane 1). Knocking down BimEL expression reduced PARP cleavage in cells expressing Htt103Q (lane 3 vs. lane 4). In addition, we also assayed the level of active caspase-3 as another indicator of apoptosis. Similarly, cells expressing Htt103Q had more active caspase-3 compared with cells expressing Htt25Q, and this increase was blocked by knocking down BimEL expression (Fig. 7A). To investigate the effect of mHtt on cell viability, we first performed an ATP assay which determines the number of viable cells in culture based on quantitation of the ATP present. Htt103Q expression reduced cell viability by ~30% compared with cells expressing Htt25Q (Fig. 7B, t-test, P = 0.0011, n = 4). Knocking down BimEL in cells expressing Htt103Q significantly increased the cell viability compared with cells expressing Htt103Q alone (Fig. 7B, t-test, P = 0.03, n = 4). We next determined the percentage of dead cells in different conditions by the trypan blue exclusion method. Similarly, the population of dead cells increased to 30% in cells expressing Htt103Q compared with 10% in cells expressing Htt25Q (Fig. 7C, t-test, P = 0.0022, n = 3). Knocking down BimEL in cells expressing Htt103Q significantly reduced cell death to 15% (Fig. 7C, t-test, P = 0.011, n = 3). Taken together, our data suggest that BimEL is necessary for mHtt-induced apoptosis.

Figure 7.

Effect of knocking down BimEL expression on mHtt-induced cell death. N2a cells were co-transfected with Htt plasmid and mouse Bim siRNA duplex. Cells were analyzed 48 hours after co-transfection. A, Immunoblotting analysis of the effect of silencing BimEL expression in mHtt-induced cell death by PARP cleavage and active caspase-3 staining. Knocking down of BimEL expression was also confirmed by immunoblotting using antibodies against BimEL. B, Analysis of the effect of silencing BimEL expression in mHtt-induced cell death by cell viability assay. C, Analysis of the effect of silencing BimEL expression in mHtt-induced cell death by the trypan blue exclusion assay. **P < 0.01 compared with cells expressing Htt25Q in the absence of BimEL silencing. #P<0.05 compared with cells expressing Htt103Q in the absence of BimEL silencing.

Discussion

Evidences of apoptosis as a cause of cell death in HD remain conflicting. While no evidence of cell death was found in a mouse model of HD until very late in disease development (Turmaine et al., 2000), it has been reported that viral vectors encoding long CAG repeats induced apoptosis and cell death in vivo (Senut et al., 2000). It is thus suggested that the progress involved in initiating apoptosis maybe extremely important for HD despite the lack of evidence linking HD to apoptosis (Hickey & Chesselet, 2003). Moreover, cleavage of mHtt by caspases releases a more toxic N-terminal fragment. Therefore, apoptosis has been clearly demonstrated with cell culture studies that express high levels of N-terminal fragment of mHtt, as in our present study. For example, expression of N-terminal fragment of mHtt in transfected PC12 cells or HEK293 cells induced DNA fragmentation, caspase-1 activity and cytochrome c release (Li et al., 2000b). However, it is unclear how polyQ-induced proteasome dysfunction and protein misfolding can be molecularly converted to neuronal death. In the present study, we showed that the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein, BimEL, is involved in relaying the signal from mHtt-induced protein misfolding and ER stress to cell death.

We found that BimEL was significantly up-regulated in response to mHtt expression in HEK293 and Neuro-2a cell lines. Our observations are also supported by the recent report showing that BimEL expression was greatly increased in a Htt knock-in mutant STHdh(Q111) striatal cell line compared with the wild type STHdh(Q7) (Kong et al., 2009). In addition, we also showed that BimEL expression was increased in R6/2 mice. Consistent with our observation, it is reported that BimEL expression was found to be enhanced in the striatum of R6/1 mice (Garcia-Martinez et al., 2007) and R6/2 mice (Zhang et al., 2003).

In mammals, there are at least seven BH3-only proteins including Bim (Huang & Strasser, 2000). Although Puma expression was not changed, we did detect a significant reduction of full length Bid expression in cells expressing Htt103. Increase of truncated Bid expression was also reported (Zhang et al., 2003). It is likely that Bim and Bid initiate distinct apoptotic pathways by responding to different stress signal. Increased ER stress and proteasome dysfunction in HD may specifically activate BimEL. This is consistent with the report that ER stress caused only a minor or no increase in Bid or puma expression (Puthalakath et al., 2007). It is also reported that activation of Bim occurs early during apoptosis in a caspase-independent manner (Puthalakath et al., 1999). It is therefore likely that Bim initiates the caspase cascade. Bid probably serves to amplify the caspase signal rather to initiate it (Yin et al., 1999). It is also reported that expression of mutant huntingtin in sympathetic superior cervical ganglion (SCG) neurons caused Hsp70 accumulation in the insoluble fractions which were prepared from cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (King et al., 2008). However, we did not detect any changes in Hsp70 expression in our preparations which were obtained from soluble cell lysates. Therefore, the discrepancy could be explained by different sample preparations. It remains interesting to see whether Hsp70 increases in our insoluble fractions.

Our data suggest that phosphorylation of BimEL plays an important role in regulating BimEL expression. ERK1/2 and JNK are the two major protein kinases identified to phosphorylate BimEL (Lei & Davis, 2003; Luciano et al., 2003; Ley et al., 2005). Phosphorylation of Ser65 in rodent BimEL (Ser69 in human BimEL) mediated by ERK1/2 promotes BimEL ubiquitination and proteasome degradation, therefore antagonizing its pro-apoptotic activity (Luciano et al., 2003; Ley et al., 2004). JNK phosphorylates BimEL at other sites, possibly Thr112, and potentiates its apoptotic activity (Hubner et al., 2008). In our present study, we have shown that both ERK1/2 and JNK are activated in cells expressing mHtt103Q. Consistently, it has also been shown that mHtt expression activated both ERK and JNK signaling pathways in PC12 and striatal cells (Apostol et al., 2006). ERK activity is protective against Htt-mediated cell death, whereas JNK promotes cell death (Apostol et al., 2006). Although the downstream target was not identified in their study, we suggest that phosphorylation of BimEL is the key event as shown by the increase of phophoSer65-BimEL. Therefore, it seems that the balance between these two opposing pathways determines the ultimate fate of the cell. We believe that there is a temporal difference in regulating ERK1/2 and JNK activity in HD. During the early stages of HD, activation of ERK1/2 phosphorylates BimEL at Ser65 and targets BimEL for proteasome degradation. When the disease progresses, mHtt forms aggregates and impairs proteasome activity, resulting in the accumulation of phosphoSer65-BimEL, contributing to the total BimEL expression. In the later stages of HD, JNK is activated and phosphorylates BimEL at other sites. This aspect of the study is currently under investigation using specific inhibitors for ERK1/2 and JNK.

It is unlikely that increased phosphoSer69-BimEL could directly increase its pro-apoptotic activity. One possible explanation is that upon phosphorylation of Ser65, ERK1/2 and JNK further induce different phosphorylation patterns at other sites which provide different signals to regulate BimEL function. Ser55 and Ser73 in addition to Ser65 was also found to be phosphorylated by ERK1/2 in transgenic mice with a series of mutant alleles that express phosphorylation-defective Bim protein and play a role in regulating Bim protein stability (Hubner et al., 2008). They also found that JNK could also phosphorylate BimEL at Thr112 and promote its pro-apoptotic activity. Consistent with these findings, a mobility shift was also observed for phosphoSer65-BimEL in cells expressing mHtt72Q and mHtt103Q when compared with cells expressing Htt25Q in our study, suggesting that some other sites were also phosphorylated in addition to Ser65. Based on the current evidence to date, we believe that phosphorylation of BimEL at Ser65 could further induce BimEL phosphorylation at Thr112 by JNK, which leads to apoptosis. This aspect of the study will be further investigated using newly reported phospho-antibodies against BimEL at Thr112 (Hubner et al., 2008).

We showed that phophoSer65-BimEL was increased in cells expressing mHtt103Q due to an impairment of proteasome activity. Nevertheless, the impairment of the UPS in HD is controversial. Most studies in cell models that express mHtt showed a decrease in proteasome activity (Bence et al., 2001; Verhoef et al., 2002; Bennett et al., 2005). However, biochemical assays on brain homogenate from the HD94 conditional mouse model of HD (Diaz-Hernandez et al., 2003) and 13-week-old R6/2 mice (Bett et al., 2006) revealed increased trypsin- and chymotrypsin-like activities. Recently, using targeted fluorescent reporters for the UPS to presynaptic or postsynaptic terminals of neurons and biochemical assays of isolated synaptosomes, Wang et al. (2008) reported impaired UPS activity in the synapses of R6/2 mice at 9 weeks. Thus it is possible that the effect of polyQ proteins on UPS activity is dependent on its accumulation and subcellular localization, which may not be detected by examining whole cell homogenates (Wang et al., 2008). Indeed, a more sensitive measurement of polyubiquitin chains by mass spectrometry revealed accumulation in polyubiquitination in R6/2 mice, a knock-in model of HD, and human HD patients, suggesting the presence of impaired UPS activity in HD brains (Bennett et al., 2007).

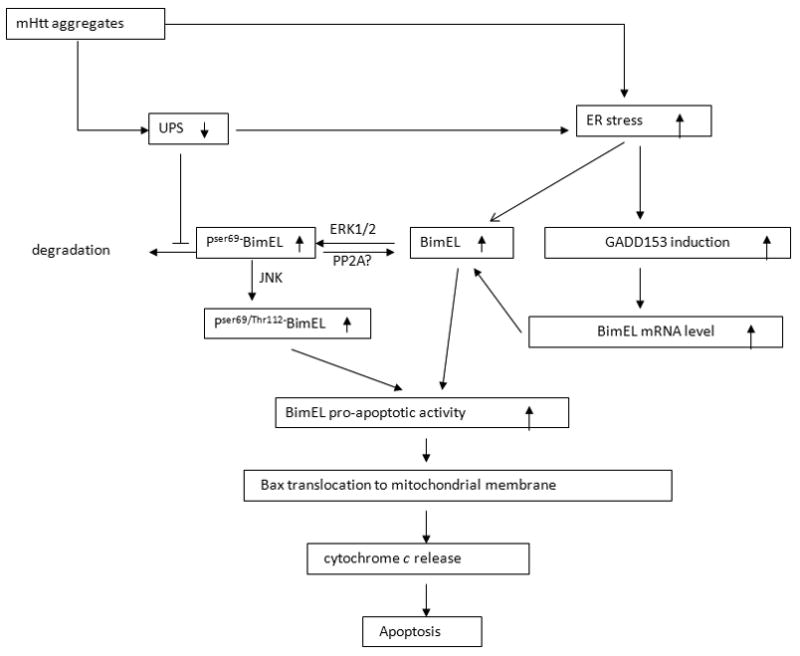

Taken together, our data suggest a novel mechanism for mHtt-induced cell death (Fig. 8). In healthy cells, BimEL is maintained at a low level, and this is achieved by low transcriptional activity and continuous phosphorylation of BimEL at Ser65 for proteasome degradation. In HD, mHtt forms aggregates and impairs UPS activity. This leads to the accumulation of phophoSer65-BimEL, which could in turn facilitate the phosphorylation of BimEL at another site, possibly Thr112, by JNK. This phosphorylation potentiates the pro-apoptotic activity of BimEL. Moreover, mHtt accumulation leads to ER stress which also increases GADD153 expression levels. This pro-apoptotic transcription factor up-regulates BimEL mRNA expression. ER stress also directly activates BimEL (Puthalakath et al., 2007). As a net result, BimEL expression is elevated which facilitates the translocation of Bax to the mitochondrial membrane and induces Bax-dependent apoptosis. Activation of other BH3-only proteins such as Bid may be involved in the later apoptotic stage (not shown in Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed model for the role of BimEL in mHtt-induced cell death. See discussion for details.

Our proposed model improves the current understanding of the molecular pathways that are altered in response to mHtt in HD. Notably, BimEL is also found to be important in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Biswas et al., 2007; Perier et al., 2007). BimEL is an essential mediator of β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity, and the expression of BimEL is found to be elevated in postmortem brains derived from AD patients (Biswas et al., 2007). In a MPTP mouse model of PD, up-regulation of BimEL was found, and loss of BimEL in transgenic mice significantly attenuated MPTP-induced dopaminergic neuronal death in the substantia nigra, a brain area specifically affected in PD (Perier et al., 2007). Since protein misfolding and UPS dysfunction have been implicated in these diseases (Lam et al., 2000; McNaught et al., 2001), our proposed model may represent a universal mechanism in the pathology of the neurodegenerative diseases that are involved with protein misfolding and aggregation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Charles E. Schmidt Family foundation, New Project Award through FAU (J.W.) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R15NS066339 (JW).

Abbreviations

The abbreviations used are:

- Bim

Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death

- BimEL

Bim extra long form

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2

- GADD153

growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 153

- Htt

Huntingtin

- PARP

poly ADP ribose polymerase

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- UPS

ubiquitin-proteasome system

References

- Apostol BL, Illes K, Pallos J, Bodai L, Wu J, Strand A, Schweitzer ES, Olson JM, Kazantsev A, Marsh JL, Thompson LM. Mutant huntingtin alters MAPK signaling pathways in PC12 and striatal cells: ERK1/2 protects against mutant huntingtin-associated toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:273–285. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker EBE, Howell J, Kodama Y, Barker PA, Bonni A. Characterization of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase-BimEL signaling pathway in neuronal apoptosis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8762–8770. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2953-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bence NF, Sampat RM, Kopito RR. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by protein aggregation. Science’s STKE. 2001;292:1552–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5521.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett E, Bence N, Jayakumar R, Kopito R. Global impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by nuclear or cytoplasmic protein aggregates precedes inclusion body formation. Molecular Cell. 2005;17:351–365. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett EJ, Shaler TA, Woodman B, Ryu KY, Zaitseva TS, Becker CH, Bates GP, Schulman H, Kopito RR. Global changes to the ubiquitin system in Huntington’s disease. Nature. 2007;448:704–708. doi: 10.1038/nature06022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bett J, Goellner G, Woodman B, Pratt G, Rechsteiner M, Bates G. Proteasome impairment does not contribute to pathogenesis in R6/2 Huntington’s disease mice: exclusion of proteasome activator REG as a therapeutic target. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:33–44. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagioli M, Pifferi S, Ragghianti M, Bucci S, Rizzuto R, Pinton P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and alteration in calcium homeostasis are involved in cadmium-induced apoptosis. Cell Calcium. 2008;43:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SC, Shi Y, Vonsattel JPG, Leung CL, Troy CM, Greene LA. Bim Is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease neurons and is required for {beta}-amyloid-induced neuronal apoptosis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:893–900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3524-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornett J, Cao F, Wang CE, Ross CA, Bates GP, Li SH, Li XJ. Polyglutamine expansion of huntingtin impairs its nuclear export. Nat Genet. 2005;37:198–204. doi: 10.1038/ng1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pril R, Fischer DF, Maat-Schieman MLC, Hobo B, de Vos RAI, Brunt ER, Hol EM, Roos RAC, van Leeuwen FW. Accumulation of aberrant ubiquitin induces aggregate formation and cell death in polyglutamine diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1803–1813. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Hernandez M, Hernandez F, Martin-Aparicio E, Gomez-Ramos P, Moran M, Castano J, Ferrer I, Avila J, Lucas J. Neuronal induction of the immunoproteasome in Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11653–11661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11653.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, Davies SW, Bates GP, Vonsattel JP, Aronin N. Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science. 1997;277:1990–1993. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Martinez JM, Perez-Navarro E, Xifro X, Canals JM, Diaz-Hernandez M, Trioulier Y, Brouillet E, Lucas JJ, Alberch J. BH3-only proteins Bid and Bim (EL) are differentially involved in neuronal dysfunction in mouse models of Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2756–2769. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J, Coffer PJ, Ham J. FOXO transcription factors directly activate bim gene expression and promote apoptosis in sympathetic neurons. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:613–622. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey MA, Chesselet MF. Apoptosis in Huntington’s disease. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2003;27:255–265. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Strasser A. BH3-only proteins-ssential initiators of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 2000;103:839–842. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubner A, Barrett T, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Multisite phosphorylation regulates Bim stability and apoptotic activity. Molecular Cell. 2008;30:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata A, Christianson JC, Bucci M, Ellerby LM, Nukina N, Forno LS, Kopito RR. Increased susceptibility of cytoplasmic over nuclear polyglutamine aggregates to autophagic degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2005;102:13135–13140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505801102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana NR, Zemskov EA, Wang G, Nukina N. Altered proteasomal function due to the expression of polyglutamine-expanded truncated N-terminal huntingtin induces apoptosis by caspase activation through mitochondrial cytochrome c release. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1049–1059. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.10.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Goemans C, Hafiz F, Prehn J, Wyttenbach A, Tolkovsky A. Cytoplasmic Inclusions of Htt Exon1 Containing an Expanded Polyglutamine Tract Suppress Execution of Apoptosis in Sympathetic Neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14401–14415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4751-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong PJ, Kil MO, Lee H, Kim SS, Johnson GV, Chun W. Increased expression of Bim contributes to the potentiation of serum deprivation-induced apoptotic cell death in Huntington inverted exclamation mark s disease knock-in striatal cell line. Neurol Res. 2009;31:77–83. doi: 10.1179/174313208X331572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krobitsch S, Lindquist S. Aggregation of huntingtin in yeast varies with the length of the polyglutamine expansion and the expression of chaperone proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2000;97:1589–1594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YA, Pickart CM, Alban A, Landon M, Jamieson C, Ramage R, Mayer RJ, Layfield R. Inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2000;97:9902–9906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170173897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei K, Davis RJ. JNK phosphorylation of Bim-related members of the Bcl2 family induces Bax-dependent apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2003;100:2432–2437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438011100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R, Ewings KE, Hadfield K, Cook SJ. Regulatory phosphorylation of Bim: sorting out the ERK from the JNK. Cell Death Differentiation. 2005;12:1008–1014. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R, Ewings KE, Hadfield K, Howes E, Balmanno K, Cook SJ. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 are serum-stimulated “Bim(EL) kinases” that bind to the BH3-only protein Bim(EL) causing its phosphorylation and turnover. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8837–8847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311578200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Li SH, Johnston H, Shelbourne PF, Li XJ. Amino-terminal fragments of mutant huntingtin show selective accumulation in striatal neurons and synaptic toxicity. Nature Genetics. 2000a;25:385–389. doi: 10.1038/78054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhu H, Xu C, Yuan J. Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 1998;94:491–502. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SH, Lam S, Cheng AL, Li XJ. Intranuclear huntingtin increases the expression of caspase-1 and induces apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2000b;9:2859–2867. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.19.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano F, Jacquel A, Colosetti P, Herrant M, Cagnol S, Pages G, Auberger P. Phosphorylation of Bim-EL by Erk1//2 on serine 69 promotes its degradation via the proteasome pathway and regulates its proapoptotic function. Oncogene. 2003;22:6785–6793. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Budihardjo I, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. Bid, a Bcl2 interacting protein, mediates cytochrome c release from mitochondria in response to activation of cell surface death receptors. Cell. 1998;94:481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81589-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaught KSP, Olanow CW, Halliwell B, Isacson O, Jenner P. Opinion: Failure of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in Parkinson’s disease. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:589–594. doi: 10.1038/35086067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen P. PARP cleavage as a means of assessing apoptosis. Methods in Molecular Medicine. 2004;88:171–182. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-406-9:171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitoh H, Matsuzawa A, Tobiume K, Saegusa K, Takeda K, Inoue K, Hori S, Kakizuka A, Ichijo H. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes & Development. 2002;16:1345–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.992302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly LA, Cullen L, Visvader J, Lindeman GJ, Print C, Bath ML, Huang DCS, Strasser A. The proapoptotic BH3-only protein Bim is expressed in hematopoietic, epithelial, neuronal, and germ Cells. American Journal of Pathology. 2000;157:449–461. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64557-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver FJ, de la Rubia G, Rolli V, Ruiz-Ruiz MC, de Murcia G, Murcia JM-d. Importance of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and its cleavage in apoptosis. Lesson from an uncleavable mutant. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33533–33539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perier C, Bove J, Wu DC, Dehay B, Choi DK, Jackson-Lewis V, Rathke-Hartlieb S, Bouillet P, Strasser A, Schulz JB, Przedborski S, Vila M. Two molecular pathways initiate mitochondria-dependent dopaminergic neurodegeneration in experimental Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2007;104:8161–8166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609874104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putcha GV, Le S, Frank S, Besirli CG, Clark K, Chu B, Alix S, Youle RJ, LaMarche A, Maroney AC. JNK-mediated BIM phosphorylation potentiates BAX-dependent apoptosis. Neuron. 2003;38:899–914. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putcha GV, Moulder KL, Golden JP, Bouillet P, Adams JA, Strasser A, Johnson EM. Induction of BIM, a proapoptotic BH3-Only BCL-2 family member, is critical for neuronal apoptosis. Neuron. 2001;29:615–628. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H, Huang DCS, O’Reilly LA, King SM, Strasser A. The proapoptotic activity of the Bcl-2 family member Bim is regulated by interaction with the dynein motor complex. Mol Cell. 1999;3:287–296. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H, O’Reilly LA, Gunn P, Lee L, Kelly PN, Huntington ND, Hughes PD, Michalak EM, McKimm-Breschkin J, Motoyama N. ER Stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell. 2007;129:1337–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senut MC, Suhr ST, Kaspar B, Gage FH. Intraneuronal aggregate formation and cell death after viral expression of expanded polyglutamine tracts in the adult rat brain. J Neurosci. 2000;20:219–229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00219.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turmaine M, Raza A, Mahal A, Mangiarini L, Bates GP, Davies SW. Nonapoptotic neurodegeneration in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8093–8097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110078997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef LGGC, Lindsten K, Masucci MG, Dantuma NP. Aggregate formation inhibits proteasomal degradation of polyglutamine proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2689–2700. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.22.2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang CE, Orr A, Tydlacka S, Li SH, Li XJ. Impaired ubiquitin-proteasome system activity in the synapses of Huntington’s disease mice. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:1177–1189. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Wang K, Gross A, Zhao Y, Zinkel S, Klocke B, Roth K, Korsmeyer S. Bid-deficient mice are resistant to Fas-induced hepatocellular apoptosis. Nature. 1999;400:886–891. doi: 10.1038/23730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Ona V, Li M, Drozda M, Dubois-Dauphin M. Sequential activation of individual caspases, and of alterations in Bcl-2 proapoptotic signals in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1184–1192. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]