Abstract

Findings regarding the link between body image and sexuality have been equivocal, possibly because of the insensitivity of many of body image measures to potential variability across sensory aspects of the body (e.g., appearance versus odor), individual body parts (e.g., genitalia versus thighs), and social settings (e.g., public versus intimate). The current study refined existing methods of evaluating women’s body image in the context of sexuality by focusing upon two highly specified dimensions: satisfaction with the visual appearance of the genitalia and self-consciousness about the genitalia during a sexual encounter. Genital appearance dissatisfaction, genital image self-consciousness, and multiple facets of sexuality were examined with a sample of 217 undergraduate women using an online survey. Path analysis revealed that greater dissatisfaction with genital appearance was associated with higher genital image self-consciousness during physical intimacy, which, in turn, was associated with lower sexual esteem, sexual satisfaction, and motivation to avoid risky sexual behavior. These findings underscore the detrimental impact of negative genital perceptions on young women’s sexual wellbeing, which is of particular concern given their vulnerability at this stage of sexual development as well as the high rates of sexually transmitted infections within this age group. Interventions that enhance satisfaction with the natural appearance of their genitalia could facilitate the development of a healthy sexual self-concept and provide long-term benefits in terms of sexual safety and satisfaction.

Keywords: body image, physical attractiveness, sexuality, sexual satisfaction, female genitalia, self esteem, sexual risk taking

Within the United States, women are socialized to value physical appearance as an integral component of their sexuality as well as their more general self-concept. Beginning at an early age, women internalize social constructions of attractiveness and learn that increased proximity to these prescribed appearance ideals is often associated with greater desirability and opportunity across sexual, social, and occupational domains (e.g., Eagly, Ashmore, Makhijani, & Longo, 1991; Morrow, McElroy, Stamper, & Wilson, 1990; Singh & Young, 1995). Furthermore, exposure to the visual scrutiny of others continually reinforces the pressure that women experience to fit the physical prototype. According to Fredrickson and Roberts’ (1997) objectification theory, such repeated subjection to physical inspection and evaluation causes women to adopt an observer’s perspective on their bodies; women come to regard themselves as merely objects, or a collection of parts, intended for use by others. This self-objectification leads to multiple negative health outcomes, both physical (e.g., disordered eating) and psychological (e.g., depression) in nature.

Body Image and Sexuality

Body image has been identified as a primary means through which self-objectification produces such undesirable health sequelae (Noll & Fredrickson, 1998; Syzmanski & Henning, 2007). Body image is a multidimensional construct used in reference to affective (e.g., shame, dysphoria), cognitive (e.g., discontent, desire for change), and behavioral (e.g., avoidance, concealment) aspects of an individual’s reaction to his or her perceived physical being (Cash & Pruzinsky, 2002; Davison & McCabe, 2005). Levels of body dissatisfaction are high among young women, with 42% of female middle- and high-school students reporting disturbance with their body shape (Ackard, Fulkerson, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2007) and with 90% of female college students reporting dissatisfaction with their body weight (Neighbors & Sobal, 2007). Furthermore, body image plays an important role in sexual wellbeing, relating to facets of both sexual safety (Gillen, Lefkowitz, & Shearer, 2006; Littleton, Breitkopf, & Berenson, 2005; Schooler, Ward, Merriwether, & Caruthers, 2005) and sexual satisfaction (Sanchez & Kiefer, 2007).

Proposed mechanisms through which body image operates to determine various sexual health outcomes include body image self-consciousness during a sexual encounter and sexual esteem, two constructs that have been consistently associated with poor body image (Sanchez & Kiefer, 2007; Weaver & Byers, 2006; Wiederman, 2000; Wiederman & Hurst, 1998) as well as repeatedly linked to various sexual health outcomes (Dove & Wiederman, 2000; Sanchez & Kiefer, 2007; Snell, Fisher, & Walters, 1993). Body image self-consciousness during a sexual encounter refers to a sense of heightened awareness about how one’s body appears to a sexual partner during physical intimacy (Wiederman, 2000). Such cognitive absorption may lead to dissociation from the immediate interaction and detract from overall physical sensation (Masters & Johnson, 1970). The extent to which women experience body image self-consciousness during sexual activity may be contingent upon their perceived deviation from physical appearance standards, such that greater perceived deviation results in heightened mental preoccupation with their perceived physical flaws. Accordingly, previous research with women has linked lower self-rated body attractiveness, greater body dissatisfaction, and increased body shame to heightened body image self-consciousness during coupled heterosexual activity (Sanchez & Kiefer, 2007; Wiederman, 2000).

Women’s cognitive preoccupation with the appearance of their bodies during sexual activity may compromise the quality of their sexual experiences indirectly by impeding their sexual esteem. Sexual esteem, or sexual self-esteem, has been described as “the value one places on oneself as a sexual being” (Mayers, Heller, & Heller, 2003, p. 270) or, alternatively, “positive regard for and confidence in the capacity to experience one’s sexuality in a satisfying and enjoyable way” (Snell & Papini, 1989, p. 256). Sexual esteem may refer specifically to one’s self-evaluation in relation to others (e.g., as a sexual partner; Wiederman & Allgeier, 1993) or include aspects of one’s own sexuality (e.g., sexual identity; Mayers et al., 2003; Rosenthal, Moore, & Flynn, 1991). Body image self-consciousness during sexual activity has been negatively related to the former conceptualization of sexual self esteem (Wiederman, 2000). Cognitive distraction during sexual activity (i.e., self-consciousness related to both appearance and performance within a sexual context) has also been negatively related to sexual esteem, explaining statistical variance above and beyond general affect, general self-focus, sexual attitudes, and body dissatisfaction (Dove & Wiederman, 2000). These findings suggest that women’s self-consciousness about their physical appearance during a sexual encounter uniquely affects their sexual esteem, at least in terms of their self-evaluation as a sexual partner.

Sexual esteem, in turn, has been linked to numerous psychological and behavioral aspects of sexual wellbeing (O’Sullivan, Meyer-Bahlburg, & McKeague, 2006; Snell et al., 1993; Van Bruggen, Runtz, & Kadlec, 2006), with higher levels of sexual esteem being related to higher levels of sexual health and satisfaction. However, research on sexual esteem as related to sexual safety in particular has been sparse and inconsistent, with some findings suggesting a positive association between sexual esteem and sexual risk-taking within “regular” (but not casual) sexual relationships (Rosenthal et al., 1991; Seal, Minichiello, & Omodei, 1997). Regardless, within the realm of sexual risk-taking, little is known about the relationship of sexual esteem to sexual motivation, a discrete and perhaps more relevant outcome to sexual esteem. Irrespective of their actual behavior (e.g., condom use), women may be increasingly motivated to protect their sexual health to the extent that they value their sexuality; thus, greater sexual esteem may lead to greater motivation to avoid risky behavior. This link merits further exploration.

The Importance of Genital Perceptions

In theory, and as outlined above, there is a clear path that links body image to body image self-consciousness, body image self-consciousness to sexual esteem, and sexual esteem to both psychological and physical components of sexual wellbeing among women. That is, a woman’s dissatisfaction with her physical appearance is likely to heighten her self-consciousness about the way she appears, resulting in the devaluation of herself as a sexual being and ultimately threatening her sexual safety and satisfaction. However, empirical findings regarding body image as a precursor to sexual wellbeing have been equivocal. For instance, Gillen et al. (2006), studying female college students, found some relationships between body image variables and sexual risk outcomes to be significant (e.g., appearance self-evaluation in relation to lifetime frequency of condom use), but not others (e.g., body dissatisfaction in relation to number of lifetime sexual partners). Davison and McCabe (2005) failed to find a significant relationship between body image and sexual satisfaction among adult women of any age. These inconsistencies cast doubt on the relevance of body image to sexual safety and satisfaction.

One explanation for this inconsistency within the literature is the insensitivity of many body image measures to attitudes toward individual body parts. Rather, existing measures commonly present the body as a single entity that survey respondents are asked to evaluate as a whole. However, from the premise that women learn to consider themselves as a collection of body parts to be used by others (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), the assumption that logically follows is that women conceive of their bodies in fragmented versus holistic terms. Accordingly, body parts may be evaluated separately and unequally. Studies of body image measuring dissatisfaction with discrete physical attributes confirm that discontent with specific features does not always parallel overall body discontent and that some body parts are more vulnerable to negative self-evaluation than others. For instance, fewer women express dissatisfaction with their face (11–20%) than with their mid-torso (50–57%) or lower torso (47–50%) (Berscheid, Walster, & Bohrnstedt, 1973; Cash & Henry, 1995; Cash, Winstead, & Janda, 1986).

As one of the regions of the female body highly eroticized within U.S. culture, the external female genitalia (i.e., vulva), including the labia minora, the labia majora, clitoris, vulval vestibule, and mons pubis, may be a physical feature that is especially salient to women when thinking about their bodies during a sexual encounter (Braun, 2005). Consequently, women’s dissatisfaction with their genital appearance may have profound implications for their sexual experience independent of the way they feel about the appearance of their body in general (or other body parts), and may be a more relevant predictor in the aforementioned pathway. Likewise, genital image self-consciousness, or heightened awareness of and preoccupation with the appearance of one’s genitals (rather than general body image self-consciousness), may be a more germane outcome of genital appearance dissatisfaction and a more significant determinant of women’s sexual esteem and, in turn, sexual wellbeing.

Women may be particularly prone to developing genital image concerns as a result of contemporary cultural influences, including media imagery and trends in cosmetic surgery. Technological advances have provided increased public access to pornographic images, many of which reflect a narrow and unrealistic range of genital appearances (Braun & Tiefer, 2010; Davis, 2002; Green, 2005). Even more mainstream sexually explicit media images, such as those published in Playboy Magazine, idealize an exclusive set of genital attributes (Schick, Rima & Calabrese, 2010), despite the fact that there is considerable variability in the size, shape, and color of women’s vulvas across the general population (Lloyd, Crouch, Mino, Liao, & Creighton, 2005). Such media representations enhance the likelihood of women developing negative feelings about their genital appearance (Braun, 2005).

The increasing popularity and publicity associated with female genital cosmetic surgery (FGCS), commonly marketed as a means of attaining a “designer vagina,” may also contribute to women’s vulnerability to genital image disturbance by encouraging conformity to genital appearance ideals via surgical modification (Braun & Tiefer, 2010; Davis, 2002). FGCS refers to a set of procedures performed on the external female genitalia, vagina, and surrounding structures that are intended to augment appearance, improve sexual functioning, and/or enhance sexual satisfaction (Goodman, 2009). Although some surgeries are sought to improve women’s genital functionality, most are undertaken without functional indications in order to address perceived flaws in appearance (Braun, 2009; Likes, Sideri, Haefner, Cunningham, & Albani, 2008). FGCS encompasses a range of techniques, including labiaplasty (the shortening of the labia minora to reduce size or increase symmetry), clitoral hood reduction (the reduction of the female clitoral prepuce), hymenoplasty (tightening of the hymenal ring), and vaginal reconstructive surgery (tightening of the vaginal introitus/canal also referred to as perineoplasty or vaginoplasty), among others (Goodman, 2009). FGCS is increasing despite the lack of rigorous scientific studies validating such procedures, inadequate training regulations and patient protections, and widespread condemnation by professional medical associations (Goodman, 2009; Liao & Creighton, 2007; Tiefer, 2008). Thus, cultural phenomena that embrace an unnatural genital appearance ideal and promote surgical efforts to attain it may threaten women’s satisfaction with the natural appearance of their own genitalia.

Within the sparse literature pertaining to genital perceptions available to date, only a few empirical studies have examined the relevance of such perceptions to sexual health outcomes, and a clear theme has yet to emerge. Positive genital perceptions have been linked to increased sexual esteem, experience, and enjoyment (Morrison, Bearden, Ellis, & Harriman, 2005; Reinholtz & Meuhlenhard, 1995) as well as to lower sexual distress, anxiety, and body image self-consciousness during sexual activity (Berman, Berman, Miles, Pollets, & Powell, 2003; Morrison et al., 2005). However, other research has found genital perceptions to be unrelated to aspects of sexual enjoyment and experience, including sexual satisfaction, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, functioning, and pain (Berman et al., 2003). This lack of clear consensus among studies may be due to variability in the psychological constructs (e.g., satisfaction, embarrassment, and shame) and sensory aspects (e.g., appearance, smell, and taste) assessed by the genital perception measures employed. Nonetheless, findings collectively suggest that genital perceptions impact women’s sexuality and overall sexual experience and that the nature of this influence is complex and poorly understood at present.

The Current Study

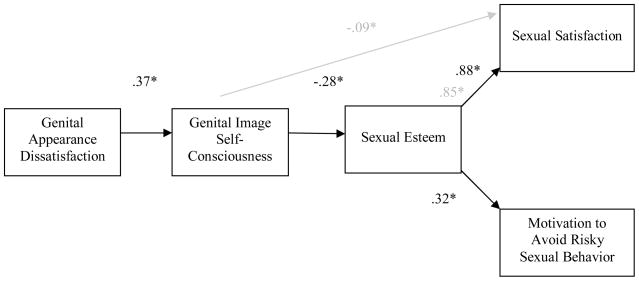

In the present study, we sought to clarify the implications of body image for women’s sexuality and extend previous work on genital perceptions by examining genital image in relation to reported genital image self-consciousness during physical intimacy, sexual esteem, sexual satisfaction, and motivation to avoid risky sex. The proposed model is displayed in Figure 1. In contrast to previous studies, the conceptualization and measurement of genital perceptions within the current study was highly specific, focusing on dissatisfaction related to a single sensory aspect of the genitals – visual appearance. Additionally, the measure used to examine self-consciousness during a sexual encounter was similarly genital-specific. We hypothesized that genital appearance dissatisfaction would be associated with greater reported genital image self-consciousness during sexual activity. We further expected that this mental preoccupation would, in turn, compromise women’s sexual esteem, ultimately limiting their motivation to avoid risky sexual behavior and jeopardizing their overall sexual satisfaction.

Figure 1.

Standardized coefficients for the original path-analytic model from genital appearance dissatisfaction to sexual wellbeing outcomes and the modified path-analytic model (indicated in gray).

* p < .05.

Method

Participants

Participants were 217 female undergraduate students attending a large, private university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. Participants were included in the study if they completed a minimum of two measures (n = 188). The sample ranged in age from 18 to 28 years (M = 19.39, SD = 1.41) and consisted of 26% freshmen, 37% sophomores, 19% juniors, and 19% seniors. Participants were predominately White (80%), and the majority reported an annual family income greater than or equal to $100,000 (73%). Ratings of present sexual orientation identity on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (other sex only) to 6 (same sex only) indicated that 96% identified as mostly or exclusively heterosexual and 1% identified as mostly or exclusively homosexual. The majority (63%) reported having ever engaged in vaginal intercourse.

Measures

Vulva appearance satisfaction

We developed the 5-itemVulva Appearance Satisfaction Scale (VASS) for our study by modifying the Body Satisfaction Scale (Rapport, Clark, & Wardle, 2000) – replacing body parts (e.g., waist) with specific components of the genitalia (e.g., labia minora). Participants rated their degree of satisfaction with the appearance of their genitalia, including the labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vaginal canal, and pubic hair. Participants were provided with a labeled anatomical diagram of the external female genitalia as a reference while completing this measure. Participants rated their satisfaction on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). Rapport et al. (2000) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .91 for the original Body Satisfaction Scale; a Cronbach’s alpha of .91 was found for the modified scale in our study. A factor analysis produced a one-factor solution with all items meeting the fair factor loading criterion, which was identified as above .45 (Comrey, 1973).

Genital image self-consciousness

Genital image self-consciousness was measured using a modified version of the Body Image Self-Consciousness Scale (BISC; Wiederman, 2000) in which the word “body” was replaced by the word “genitals” for each of the ten items included. For example, the item “I would feel very nervous if a partner were to explore my body before or after having sex” was changed to “I would feel very nervous if a partner were to explore my genitals before or after having sex.” The measure assessed the degree of self-consciousness the participants reported feeling about their genitalia while engaging in various sexual activities. Items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (always). Wiederman (2000) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .94 for the original BISC scale; a Cronbach’s alpha of .94 was found for the modified scale in our study. Factor analysis results indicated a one-factor solution with all items meeting the fair factor loading criterion.

Motivation to avoid risky sex, sexual esteem, and sexual satisfaction

The Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept Questionnaire (MSSCQ; Snell, 1998) is a 101-item self-report measure that assesses sexual health. For our study, subscales measuring motivation to avoid risky sex, sexual esteem, and sexual satisfaction were used, each of which consisted of five items. All sexual outcome measures did not specify the activities involved and included both imagined and actual events. Sample items include: “I am motivated to avoid engaging in risky (i.e., unprotected) sexual behavior” (motivation to avoid risky sex); “I am pleased with how I handle my own sexual tendencies and behaviors” (sexual esteem); and “I am satisfied with the status of my own sexual fulfillment” (sexual satisfaction). Participants rated the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (very characteristic of me). Several items were reverse scored so that higher scores indicated increased endorsement of the construct for all items. Item scores were averaged in order to compute subscale scores. Cronbach’s alphas in our study were consistent with past reports (Snell, 1998). Cronbach alphas for our total sample [motivation to avoid risky sex (α = .75), sexual esteem (α = .90), and sexual satisfaction (α = .93)], our sexually active subsample [motivation to avoid risky sex (α = .70), sexual esteem (α = .89), and sexual satisfaction (α = .89)], and our non-sexually active subsample [motivation to avoid risky sex (α = .80), sexual esteem (α = .88), and sexual satisfaction (α = .93)] were all acceptable.

Design and Procedure

Our study was part of a larger data collection examining young women’s genital discontent and sexuality. Participants were recruited through an undergraduate psychology participant pool and compensated with course credit. Informed consent and survey questions were completed on a secure online data collection site. By administering a web-based survey, participants were able to complete the study in a private setting. All data collection procedures were anonymous, and survey access by others who had not registered through the psychology research system was prohibited.

Results

Means and standard deviations for all scales are presented in Table 1. In order to investigate the bivariate relationships among the paths in the model, we conducted several Pearson Product Moment Correlation analyses (see Table 1). With the exception of the relationship of motivation to avoid risky sex to both vulva appearance dissatisfaction and genital image self-consciousness, all variables were significantly related to one another in the hypothesized directions.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations and Intercorrelations amongst Measures of Genital Perception and Sexual Wellbeing

| Measure | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Vulva Appearance Dissatisfaction | 17.74 | 4.52 | - | .39*** | −.21** | .00 | −.22** |

| 2. Genital Image Self-Consciousness | 23.15 | 11.62 | - | - | −.28*** | −.01 | −.34*** |

| 3. Sexual Esteem | 3.30 | 1.12 | - | - | - | .30*** | .88*** |

| 4. Motivation to Avoid Risky Sex | 4.19 | .92 | - | - | - | - | −.34** |

| 5. Sexual Satisfaction | 3.19 | 1.22 | - | - | - | - | - |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Prior to testing the full path, we tested for mediation amongst the variables using Baron and Kenny’s (1986) four-step test of mediation with Amos 5.0 (Arbuckle, 2003). First, we investigated whether genital image self-consciousness mediated the relationship between vulva appearance dissatisfaction and sexual esteem. In accordance with Baron and Kenny’s four steps, vulva appearance dissatisfaction was related to both genital image self-consciousness, β = .97, t(176) = −5.22, p < .001, and sexual esteem, β = −.06,t(176) = 3.11, p =.002, at the bivariate level. However, when both vulva appearance dissatisfaction and genital image self-consciousness were entered into the model predicting sexual esteem, the relationship between genital image self-consciousness and sexual esteem was significant, β = −.02, t(176) = −.2.98, p =.004, but the previously negative relationship between vulva appearance dissatisfaction and sexual esteem became nonsignificant,β = .03, t(176) = 1.41, p =.161, indicating that genital image self-consciousness fully mediated the relationship between vulva appearance dissatisfaction and sexual esteem.

Similarly, sexual esteem was tested as a mediator of the relationships between genital image self-consciousness and both sexual outcome variables. The nonsignificant bivariate relationship between genital image self-consciousness and motivation to avoid risky sex, β = .00, t(176) = .09, p =.931, failed to meet Baron and Kenny’s (1986) first criterion for establishing sexual esteem as a mediator of the relationship between genital image self-consciousness and motivation to avoid risky sex. However, genital image self-consciousness and sexual satisfaction were significantly related to one another at the bivariate level, β = −.04, t(176) = −4.70, p < .001, as was genital image self-consciousness and sexual esteem, β = −.03, t(176) = −3.91, p < .001. Further, when both genital image self-consciousness and sexual esteem were entered into the model predicting sexual satisfaction, the relationship between sexual esteem and sexual satisfaction was significant, β = .92, t(169) = 22.75, p < .001, and the relationship between genital image self-consciousness and sexual satisfaction became less significant than it was at the bivariate level, β = −.01, t(176) = −2.44, p =.016, indicating partial mediation according to the Sobel test (p < .001). Thus, sexual esteem was not established as a mediator of the relationship between genital image self-consciousness and motivation to avoid risky sex, but it was established as a mediator of the relationship between genital image self-consciousness and sexual satisfaction.

Next, the hypothesized path was tested using structural equation modeling in order to control for correlated error terms. All variables in the model were tested as manifest variables. As seen in Figure 1, all paths in the model reached significance in the hypothesized directions. The nonsignificant chi-square indicated that the model was an adequate fit of the data. In addition, we also assessed the fit of the model to the data by comparing several goodness-of-fit indicators to preset criteria. A model with a comparative fit index (CFI) or incremental fit index (IFI) over .90 is considered to be an adequate fit for the data, whereas a model with fit indices over .95 is considered to be a good fit (Byrne, 2001). Additionally, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value below .05 indicates a good fit of the model (Kenny, 2008). In accordance with the stated criteria, two of the goodness-of-fit measures in our study indicated that the model was a good fit for the data; however, the RMSEA did not meet the preset criterion (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Path-Analytic Models Testing the Relationship between Genital Perceptions and Sexual Health

| Path-Analytic Models | Fit Indices |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFI | IFI | RMSEA | X2 | |

| Original Path-Analytic Model | .98 | .98 | .08 | 12.39 |

| Modified Path-Analytic Model | 1.00 | 1.00 | .04 | 6.22 |

| Reverse Path-Analytic Model. | .95 | .95 | .13 | 22.41*** |

| Alternative Model: Reversed Modified Model | .97 | .97 | .11 | 16.42** |

| Alternative Model: Reversed Genital Appearance Dissatisfaction and Genital Image Self-Consciousness | .96 | .96 | .11 | 17.59** |

| Alternative Model: Reversed Sexual Esteem and Sexual Satisfaction | .97 | .97 | .09 | 14.38* |

| Original model excluding all participants who reported no prior history of heterosexual vaginal intercourse | 1.00 | 1.00 | .00 | 4.26 |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Although the goodness-of-fit measures generally indicated that the model was a good fit of the data, we examined the modification indices in order to investigate the fit of alternative models. All paths in the original model were statistically significant, precluding their removal. However, an examination of the modification indices suggested that the addition of a path from genital image self-consciousness to sexual satisfaction would increase the overall fit (see Figure 1). As with the previous model, the non-significant chi-square indicated that the alternative model was a good fit of the data. However, unlike in the previous model, all three fit measures indicated that the model was a good fit of the data (see Table 2). We calculated the change in fit between the models in order to assess whether the alternative model was a significantly better model than the original model. The significant change in χ2 indicates that the alternative model was a significantly better fit of the data than the original model, χ2 (1) = 6.17, p < .001.

Because the dataset were cross-sectional, we wished to test several alternate models, with reversed causal order including two paths from sexual satisfaction/motivation to avoid risky sex to genital appearance dissatisfaction, to investigate whether they fit equally well. With the exception of the relationship of sexual esteem to genital image self-consciousness, all paths were significant related in the hypothesized direction. However, as compared to the previous model, the significant chi-squares and fit indices indicated that the fit of these models were inferior. Thus, we can conclude that the reversed paths did not fit the data as well as the path depicted in Figure 1.

Next, we assessed whether participants’ reported heterosexual vaginal intercourse experience moderated the relationships among the variables. Prior to testing for moderation, we centered all the variables, as recommended by Aiken & West (1991). The interaction between vulva appearance dissatisfaction and sexual intercourse history was not significantly related to genital image self-consciousness, F (11, 166) = 1.57, p =.114, and the interaction between genital image self-consciousness and sexual intercourse history was not significantly related to sexual esteem, F (21, 169) = .78, p =.731. Similarly, the interaction between sexual esteem and sexual intercourse history was not significantly related to either sexual motivation to avoid risky sex, F (17, 185) = 1.40, p =.135, or sexual satisfaction, F (17, 185) = .95, p =.527. Thus, sexual intercourse did not moderate the relationship between any of the paths in our model.

Finally, we reassessed the model after excluding all participants who reported no prior history of heterosexual vaginal intercourse. All paths were significant with the exception of the relationship from genital image self-consciousness to sexual esteem. However, as with the larger sample, the fit measures and the non-significant chi-square indicated that the model was a good fit of the data (see Table 2).

Discussion

The current findings underscore the importance of women’s perceived genital attractiveness to multiple aspects of their sexuality. Our results support the proposed theoretical model, indicating genital appearance dissatisfaction may have harmful consequences for both sexual satisfaction and sexual risk among college women due to its detrimental impact on genital image self-consciousness and sexual esteem. Our findings are consistent with extant research linking negative genital perceptions to greater body image self-consciousness during physical intimacy, reduced sexual esteem, and decreased enjoyment of sexual activities (Morrison et al., 2005; Reinholtz & Muehlenhard, 1995). However, they are not unanimously supported within the genital perception literature (e.g., Berman et al., 2003), which may be explained methodologically.

A major strength of our study was the sensitivity of the measures we employed. Notably, we explored attitudes and cognitions specific to the visual appearance of the external genitalia in relation to sexual wellbeing given that this sensory aspect and this set of physical features are likely to be particularly salient within a sexual encounter. In addition, sexual context was specified in measuring genital image self-consciousness because such self-consciousness is likely to be substantially elevated during sexual interactions relative to other situations in which genital exposure is generally limited. Our study builds upon previous research highlighting the importance of context specificity in studying body image in relation to sexuality (Yamamiya, Cash, & Thompson, 2006).

The implications of genital appearance dissatisfaction for both physical and psychological aspects of sexual wellbeing are of particular concern within the college student population because young women may be especially vulnerable to forming negative genital perceptions at this stage of their development. According to Fredrickson and Roberts (1997), it is during adolescence that women first experience the “culture of sexual objectification” as a result of the physical changes they undergo throughout their teenage years. For the first time, young women become aware of being appraised as a body or a collection of body parts as opposed to a complete, integrated person. This realization may prompt women to become especially concerned with the presentation of their body and its individual parts. Moreover, because women’s sexual exploration and experimentation often parallel their physical maturation, young adulthood may be a time that women are not only focused on their physical appearance in general but also concerned with their genital appearance in particular. Furthermore, increased access to pornography (likely exposing women to images of unrealistic vulvas) and the rising popularity of FGCS (promoting physical modification to attain the vulva ideal) may enhance feelings of distress about genital appearance (Braun & Tiefer, 2010; Davis, 2002; Green, 2005) and may make this cultural shift most likely to impact younger generations of women.

The vulnerability of young women to genital appearance dissatisfaction is especially disconcerting because these negative repercussions may be exceptionally damaging to women’s sexual wellbeing at this developmental stage. First, women’s early sexual experiences may be extremely meaningful to the development of their sexual self-concept, or sense of themselves as sexual beings. These initial experiences may guide their understanding of both physical and emotional aspects of their sexuality. Reduced sexual satisfaction during these formative years may impinge upon the development of a healthy sexual self-concept and set the stage for future sexual difficulties and concerns. Second, decreased motivation to avoid risky sex may lead to greater exposure to HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and, hence, a greater likelihood of infection. This possibility is of particular concern given the growing prevalence rates of HIV/AIDS and other STIs among young people. In 2006, 15% of all newly diagnosed cases of HIV occurred among people ages 15–24; among women, the vast majority of infections occurred via heterosexual contact (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008). Further, recent surveillance data suggest that within the U.S. female population, adolescents and young adults have the highest rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and human papillomavirus (CDC, 2007). In addition to increasing susceptibility to STIs, reduced motivation to avoid risky sex increases the risk of unwanted pregnancy, an occurrence that may be particularly difficult for young women to cope with given their potential lack of financial resources at this age. Thus, the sexual health outcomes associated with genital appearance dissatisfaction have the potential to be far-reaching, long-lasting, and particularly devastating among young women.

There were several methodological limitations in the current study. First, the cross-sectional design prohibits inferences about causality. For instance, although we assumed that genital appearance dissatisfaction caused reduced sexual satisfaction, it is possible that unsatisfactory sexual experiences drove women to feel less positively about their genitalia. Alternatively, women with low motivation to avoid risky behavior may have been more likely to contract an STI; certain STIs that are externally visible, such as genital warts or herpes, may have contributed to lower genital appearance satisfaction. However, statistical testing of alternative models within the current data set suggested that the hypothesized path was a better fit of the data than the inversed model.

Second, when we restricted the sample to women who were sexually active only, the path from genital image self-consciousness to sexual esteem was no longer significant. It is possible that this was due to the smaller sample size. Another possible explanation is that the women included in the full sample who had not yet engaged in vaginal intercourse may have limited their sexual activity because of their strong genital image self-consciousness or low levels of sexual esteem. If so, this decreased variation could explain why the negative relation between self-consciousness and sexual esteem was higher when thse women were included in the analyses. Future research should examine the relation between these two constructs and attend to possible variation based on the participants’ level of sexual experience.

Third, the sample consisted primarily of heterosexual, Caucasian college students, aged 18 to 28, who were attending an expensive, private university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. Generalization of findings to other segments of the female population in the United States or women of other cultures is accordingly compromised. For example, genital appearance may be more or less salient within a sexual encounter in different cultures depending on the way sexual encounters are scripted to unfold and the specific emphasis placed on the genitalia within a sexual context. Specifically, women may feel less self-conscious about the appearance of their genitals during sexual activity if cunnilingus or other acts that enhance genital visibility are not common. Alternatively, appearance in general may be less central to women’s sexuality among other populations, such that even if women are dissatisfied with the appearance of their genitalia, such dissatisfaction does not substantially affect their sexual experience or motivations. Furthermore, genital appearance ideals presented in other cultures may be more inclusive of the wide variability in size, shape, and color of the female genitalia within the regular population (Lloyd et al., 2005), and consequently, genital appearance dissatisfaction may be less common and less relevant to sexual wellbeing. For instance, Green (2005) posited that in Japan the condition of extremely large labia is not seen as unattractive as it is in many Western nations, but rather accepted and regarded as a sexual “delicacy.”

Finally, the implications of the current study for sexual health are limited by the measure of sexual risk employed. Although findings highlight the relevance of genital appearance satisfaction to sexual safety intentions, motivation to engage in safer sex does not necessarily translate into safer sexual behavior. This disconnect between intention and behavior in the realm of sexuality has been documented previously and has been explained by barriers such as concerns about discussing or using condoms and fear of partner reaction (e.g., Amaro, 1995; Gavey, McPhillips, & Doherty, 2001).

Our paper examined satisfaction with one sensory aspect of the genitalia (i.e., visual appearance) in relation to sexual health outcomes. Women may also be inclined to develop dissatisfaction with other aspects of their genitals (e.g., odor and taste) given sociocultural representations of the female genitalia not only as unattractive, but also as dirty, malodorous, and generally unpleasant (Braun & Wilkinson, 2001; Merskin, 1999; Simes & Berg, 2001) – a point illustrated by the multimillion dollar industry marketing “corrective” products such as deodorant sprays, feminine wipes, and douching kits (Martino, Youngpairoj, & Vermund, 2004). Odor has been identified as one of women’s primary loci of concern regarding their genitalia, with more than one in five female students expressing dissatisfaction with the odor of their genitalia (Morrison et al., 2005). Moreover, negative perceptions about the smell and taste of one’s genitalia have previously been linked to lower participation in and enjoyment of various sexual activities (Reinholtz & Muehlenhard, 1995). Further research examining the relative contribution of women’s dissatisfaction with these other facets of their genitalia to genital image self-consciousness and sexual wellbeing is warranted.

In addition to examining a woman’s dissatisfaction with various aspects of her own genitalia in regard to sexual outcomes, it may also be useful to explore her perceptions about her sexual partner’s dissatisfaction with her genitalia relative to these same outcome variables. Previous research has linked women’s anxiety about a male sexual partner’s response to their genitalia with reduced enjoyment during sexual activity. Although, in reality, men typically rate their female partners’ genitalia more favorably than women rate their own genitalia (Reinholtz & Muehlenhard, 1995), women may nonetheless perceive or anticipate a negative response from their partners irrespective of their partners’ actual reactions. Similar to personal dissatisfaction with genital appearance, perceived partner dissatisfaction may increase genital image self-consciousness during sexual activity and detrimentally impact sexual esteem, sexual satisfaction, and motivation to avoid risky sexual behavior, and it therefore is an intriguing point for future inquiry.

Furthermore, it will be important to examine these issues not only within a heterosexual context but also among women who have sexual relations with other women. Although we are unaware of such studies, the literature addressing general body image concerns among women who have sexual relations with women is equivocal. Some studies suggest that lesbians are protected in this domain (e.g., less dissatisfied with their body image [Polimeni, Austin, & Kavanagh, 2009] and least concerned with physical appearance [Strong, Williamson, Netemeyer, & Geer, 2000]), which might imply that women who have sexual relations with women have less to fear about their partners’ reactions to their genitals. However, other studies found no advantage of one sexual orientation over another in the body image domain (e.g., Hill & Fischer, 2008; Striegel-Moore, Tucker, & Hsu, 1990). Thus, future research among women with diverse sexual orientations and behaviors is necessary.

In addition to examining the influence of men’s perceptions of women’s genitalia on women’s sexual wellbeing, the influence of men’s perceptions of their own genitalia on their own sexual wellbeing is worthy of examination. Men’s sexual wellbeing may be similarly vulnerable to negative perceptions about their genital appearance, particularly given the cultural emphasis on penis size and its alleged ties to masculinity (Lever, Frederick, & Peplau, 2006). Thus, although we expect the nature of dissatisfaction to differ across the sexes (e.g., men desiring bigger penises and women desiring smaller labia minora), it stands to reason that both sexes are negatively affected by cultural prescriptions regarding genitalia and may experience sexual consequences as a result of internalizing such norms (e.g., Braun & Tiefer, 2010).

In light of the potential gravity of the sexual consequences stemming from genital appearance dissatisfaction, it is important to address cultural factors contributing to the development and maintenance of such dissatisfaction among young women, including unrealistic genital representations in the media and public promotion of FGCS. Genital appearance dissatisfaction may be dispelled by exposing women to images of female genitalia of a variety of colors, shapes, and sizes in order to minimize their perceived deviation from the norm and to broaden their conceptualization of the ideal. In addition, increasing public awareness of the health risks and questionable merits of FGCS may help to curtail its growing popularity (Braun & Tiefer, 2010). Finally, strengthening women’s own resistance to threats to their sexual well-being, for example by promoting feminist attitudes (Schick, Zucker, & Bay-Cheng, 2008), may reduce body monitoring. Ultimately, enhancing women’s satisfaction with the natural appearance of their genitalia and reducing the pressure they experience to seek physical modification would facilitate the development of a healthy sexual self-concept and maximize sexual safety and satisfaction among women.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Kristin Mann for her assistance with the data collection. Sarah K. Calabrese was supported by Award Number F31MH085584 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this paper was presented at presented at the 117th Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association Annual Meeting: Toronto, Canada.

Contributor Information

Vanessa R. Schick, Department of Psychology, The George Washington University

Sarah K. Calabrese, Department of Psychology, The George Washington University

Brandi N. Rima, Department of Psychology, The George Washington University

Alyssa N. Zucker, Department of Psychology and Women’s Studies, The George Washington University

References

- Ackard DM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Prevalence and utility of DSM-IV eating disorder diagnostic criteria among youth. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(5):409–417. doi: 10.1002/eat.20389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H. Love, sex, and power: Considering women’s realities in HIV prevention. American Psychologist. 1995;50:437–447. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.6.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 5.0 [Computer Software] Chicago: SPSS; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman L, Berman J, Miles M, Pollets D, Powell JA. Genital self-image as a component of sexual health: Relationship between genital self-image, female sexual function, and quality of life measures. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2003;29(1):11–21. doi: 10.1080/713847124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, Walster E, Bohrnstedt G. The happy American body: A survey report. Psychology Today. 1973;7:119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V. ‘The women are doing it for themselves’: The rhetoric of choice and agency around female genital ‘cosmetic surgery’. Australian Feminist Studies. 2009;24:233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V. In search of (better) sexual pleasure: Female genital ‘cosmetic’ surgery. Sexualities. 2005;8(4):407–427. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Wilkinson S. Socio-cultural representations of the vagina. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2001;18(1):17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Tiefer L. The ‘designer vagina’ and the pathologisation of female genital diversity: Interventions for change. Radical Psychology. 2010;8(1) [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, Henry PE. Women’s body images: The results of a national survey in the U.S.A. Sex Roles. 1995;33(1/2):19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, Pruzinsky T, editors. Body image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, Winstead BA, Janda LH. The great American shape-up. Psychology Today. 1986;20:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. 2008 Retrieved June 2, 2008, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. 2007 Retrieved June 2, 2008, from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/pdf/Surv2006.pdf.

- Comrey AL. A first course in factor analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Davis SW. Loose lips sink ships. Feminist Studies. 2002;28:7–35. [Google Scholar]

- Davison TE, McCabe MP. Relationships between men’s and women’s body image and their psychological, social, and sexual functioning. Sex Roles. 2005;52(7/8):463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Dove NL, Wiederman MW. Cognitive distraction and women’s sexual functioning. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2000;26:67–78. doi: 10.1080/009262300278650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Ashmore RD, Makhijani MG, Longo LC. What is beautiful is good, but…: A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(1):109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Roberts TA. Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21:173–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gavey N, McPhillips K, Doherty M. If it’s not on it’s not on-or is it? Discursive constraints on women’s condom use. Gender & Society. 2001;15:917–934. [Google Scholar]

- Gillen MM, Lefkowitz ES, Shearer CL. Does body image play a role in risky sexual behavior and attitudes? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(2):243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MP. Female cosmetic genital surgery. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009;113(1):154–159. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318190c0ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green FJ. From clitoridectomies to ‘designer vaginas’: The medical construction of heteronormative female bodies and sexuality through female genital cutting. Sexualities, Evolution, and Gender. 2005;7:153–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hill MS, Fischer AR. Examining objectification theory: Lesbian and heterosexual women’s experiences with sexual- and self-objectification. Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:745–776. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Measuring model fit. 2008 Retrieved June 10, 2008, from http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm.

- Lever J, Frederick DA, Peplau LA. Does size matter? Men’s and women’s views on penis size across the lifespan. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2006;7:129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Liao LM, Creighton SM. Requests for cosmetic genitoplasty: How should healthcare providers respond? British Medical Journal. 2007;334:1090–1092. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39206.422269.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likes WM, Sideri M, Haefner H, Cunningham P, Albani F. Aesthetic practice of labial reduction. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2008;12:210–216. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318161f9ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Breitkopf CR, Berenson A. Body image and risky sexual behaviors: An investigation in a tri-ethnic sample. Body Image. 2005;2:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J, Crouch NS, Minto CL, Liao LM, Creighton SM. Female genital appearance: ‘Normality’ unfolds. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;112:643–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino JL, Youngpairoj S, Vermund SH. Vaginal douching: Personal practices and public policies. Journal of Women’s Health. 2004;13:1048–1065. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters WJ, Johnson VE. Human sexual inadequacy. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Mayers KS, Heller DK, Heller JA. Damaged sexual self-esteem: A kind of disability. Sexuality and Disability. 2003;21(4):269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Merskin D. Adolescence, advertising, and the ideology of menstruation. Sex Roles. 1999;40:941–957. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison TG, Bearden A, Ellis SR, Harriman R. Correlates of genital perceptions among Canadian post-secondary students. Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality. 2005;8 Retrieved from http://www.ejhs.org/volume8/GenitalPerceptions.htm.

- Morrow PC, McElroy JC, Stamper BG, Wilson MA. The effects of physical attractiveness and other demographic characteristics on promotion decisions. Journal of Management. 1990;16(4):723–736. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors LA, Sobal J. Prevalence and magnitude of body weight and shape dissatisfaction among university students. Eating Behaviors. 2007;8:429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll SM, Fredrickson BL. A mediational model linking self-objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1998;22:623–636. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, McKeague IW. The development of the sexual self-concept inventory for early adolescent girls. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2006;30:139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Polimeni AM, Austin SB, Kavanagh AM. Sexual orientation and weight, body image, and weight control practices among young Australian women. Journal of Women’s Health. 2009;18:355–362. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapport L, Clark M, Wardle J. Evaluation of a modified cognitive-behavioural programme for weight management. International Journal of Obesity. 2000;24:1726–1737. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinholtz RK, Muehlenhard CL. Genital perceptions and sexual activity in a college population. The Journal of Sex Research. 1995;32(2):155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal D, Moore S, Flynn I. Adolescent self-efficacy, self-esteem, and sexual risk-taking. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 1991;1:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez DT, Kiefer AK. Body concerns in and out of the bedroom: Implications for sexual pleasure and problems. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;3:808–820. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick VR, Zucker AN, Bay-Cheng LY. Safer, better sex through feminism: The role of feminist ideology in women’s sexual well-being. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Schick VR, Rima BN, Calabrese SK. Evulvalution: The portrayal of women’s external genitalia and general physique across time and the current Barbie doll ideals. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47:1–9. doi: 10.1080/00224490903308404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler D, Ward ML, Merriwether A, Caruthers A. Cycles of shame: Menstrual shame, body shame, and sexual decision making. The Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(4):324–334. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal A, Minichiello V, Omodei M. Young women’s sexual risk taking behaviour: Re-visiting the influences of sexual self-efficacy and sexual self-esteem. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1997;8:159–165. doi: 10.1258/0956462971919822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simes MR, Berg DH. Surreptitious learning: Menarche and menstrual product advertisements. Health Care for Women International. 2001;22:455–469. doi: 10.1080/073993301317094281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D, Young RK. Body weight, waist-to-hip ratio, breasts, and hips: Role in judgments of female attractiveness and desirability for relationships. Ethology and Sociobiology. 1995;16:483–507. [Google Scholar]

- Snell WE., Jr . The Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept Questionnaire. In: Davis CM, Yarber WL, Baurerman R, Schreer G, Davis SL, editors. Sexuality-related measures: A compendium. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 521–524. [Google Scholar]

- Snell WE, Jr, Fisher TD, Walters AS. The Multidimensional Sexuality Questionnaire: An objective self-report measure of psychological tendencies associated with human sexuality. Annals of Sex Research. 1993;6:27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Snell WE, Jr, Papini DR. The Sexuality Scale: An instrument to measure sexual self-esteem, sexual-depression, and sexual-preoccupation. The Journal of Sex Research. 1989;26(2):1989. [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Tucker N, Hsu J. Body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating in lesbian college students. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1990;9:493–500. [Google Scholar]

- Strong SM, Williamson DA, Netemeyer RG, Geer JH. Eating disorder symptoms and concerns about body differ as a function of gender and sexual orientation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2000;19:240–255. [Google Scholar]

- Syzmanski DM, Henning SL. The role of self-objectification in women’s depression: A test of objectification theory. Sex Roles. 2007;56:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tiefer L. Female genital cosmetic surgery: Freakish or inevitable? Analysis from medical marketing, bioethics, and feminist theory. Feminism & Psychology. 2008;18:466–479. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bruggen LK, Runtz MG, Kadlec H. Sexual revictimization: The role of sexual self-esteem and dysfunctional sexual behaviors. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11(2):131–145. doi: 10.1177/1077559505285780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver AD, Byers ES. The relationships among body image, body mass index, exercise, and sexual functioning in heterosexual women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2006;30:333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman MW. Women’s body image self-consciousness during physical intimacy with a partner. The Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37(1):60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman MW, Allgeier ER. The measurement of sexual-esteem: Investigation of Snell and Papini’s (1989) Sexuality Scale. Journal of Research on Personality. 1993;27:88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman MW, Hurst SR. Body size, physical attractiveness, and body image among young adult women: Relationships to sexual experience and self-esteem. The Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35(3):272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamiya Y, Cash TF, Thompson JK. Sexual experiences among college women: The differential effects of general versus contextual body images on sexuality. Sex Roles. 2006;55:421–427. [Google Scholar]