Abstract

Objective. This study was designed to determine the effects of different short-term exercise programs on menopausal symptoms, psychological health, and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Material and Methods. Forty-two women were chosen from volunteering postmenopausal women presenting to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Bayındır Hospital between March and December 2009. The women aged 45–60 years and experiencing menopause naturally were included in the study. They were randomly divided into aerobic (n = 18) and resistance (n = 18) exercise groups. The women exercised 3 days per week for 8 weeks under the supervision of a physiotherapist. Aerobic exercise training was performed through a bicycle ergometer. Before and after the training, lipid profiles were measured and menopausal symptoms, psychological health, depression, and the quality of life were assessed through questionnaires. Results. In both exercise groups, no significant changes in lipid profiles were observed. In the resistance exercise group, excluding the urogenital complaints, there were significant improvements in all subscales of Menopausal Rating Scale (MRS). In the resistance exercise group, excluding the phobic anxiety, there were significant improvements in all subscales of The Symptom Checklist. Depression levels significantly decreased in both groups. Improvements were observed in all subscales of menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire in both groups except for sexual symptoms. Conclusion. Resistance exercise and aerobic exercise were found to have a positive impact on menopausal symptoms, psychological health, depression, and quality of life.

1. Introduction

Menopause is an adaptation process during which women go through a new biological state. This process is accompanied by many biological and psychosocial changes. During menopause, loss of skin flexibility, a decrease in libido, sexual dysfunction, an increase in the risk of cardiovascular diseases, urinary tract infections, incontinence, bone loss, and somatic and vasomotor symptoms may appear [1, 2]. Depressed mood, sleep disorders, and other psychological problems reduce the quality of life in postmenopausal women [3].

Due to the complexity of menopausal symptoms, many different alternatives to hormone replacement therapy have been developed to control menopausal symptoms. They include the use of herbal drugs, diet/nourishment, exercise programs, and lifestyle modification programs [4]. It is evident that exercise is becoming one of the most important alternative treatment procedures [3, 5]. There are studies in the literature that deal with the effect of exercise on menopausal symptoms. It is worth noting that in most of the studies aerobic and resistance exercises are used together [6]. It is also noteworthy that there are a limited number of studies that compare and contrast different types of exercise for postmenopausal women in terms of effectiveness. The aim of this study is to determine the effects of different short-term exercise programs on menopausal symptoms, psychological health, and quality of life in postmenopausal women and to evaluate the results in the light of the literature.

2. Material and Methods

Forty-two women were chosen from volunteering postmenopausal women presenting to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Bayındır Hospital between March and December 2009. Written approval was obtained from the ethical committee. The women fulfilling the inclusion criteria were informed as to the purpose, method, content, usefulness, and duration of the study and were included in the study after they gave written consent. The women aged 45–60 years and experiencing menopause naturally were included in the study. The exclusion criteria were severe metabolic and endocrine diseases, receiving hormone replacement treatment, and surgical menopause. Furthermore, the patients taking selective estrogen receptor agonists (raloxifene), the patients receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy for any cancer types, patients taking antidepressants or antipsychotics, patients unable to exercise, and those exercising regularly for the past 6 months were not included in the study.

Prior to the study, 42 postmenopausal women were randomly divided into two different exercise groups: aerobic and resistance. Three cases from each group were unable to complete the study because of personal reasons. Data collected from these cases were not included in statistical analyses. Both groups attended the exercise programs 3 days per week for 8 weeks under the supervision of a physiotherapist.

Before evaluation, ages, heights, and body mass indexes (BMI) of the cases were recorded. They were asked their professions, personal and family histories, educations and marital statuses, the ages when they went through menopause, their most serious health complaints, and medications they were using regularly. Before and after the study, of both groups blood lipid profiles and menopausal symptoms (Menopause Rating Scale-MRS), psychological symptoms (SCL-90-R The Symptom Checklist), depression (Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), quality of life regarding health evaluations; Menopause-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MENQOL) were carried out. MRS, MENQOL ve BDI questionnaires were done before the end of the study by only a physiotherapist as face to face and answer to question. It was taken blood samples of patients were taken before and after the study for lipid profile analyses. Lipid values of those included in the study were measured by using Beckman Coulter (SYNCHRON/Clinical system CX9 PRO) criteria. For evaluating menopausal symptoms, menopause symptoms evaluation scale was used [7]. Evaluation of psychological symptoms was carried out by using Symptom Scan List (SCL-90-R) [8]. Evaluation of depression was carried out by using Beck Depression Inventory [9, 10]. In evaluation of quality of life regarding health Menopause-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MENQOL) was used [11, 12].

Prior to aerobic exercise training, a submaximal and symptom-limited test on an ergonomic bike was carried out in patients with the aim of determining instructional workload. For the training, an ergonomic bike test was carried out in patients, ECG and a pulse controlled ergometric bike (Tunturi 460 ECG Pulse Controlled Ergometer) were used (Figure. Bike). Following warm up exercises, each case was trained on the bike for 40–45 minutes. Cases in the resistance exercise group were trained with elastic bands on big muscle groups. Prior to resistance exercise training, perceived exertion scale and multimax repeated system were used so as to determine the elastic resistance regime of cases [13, 14].

Exercises used in the resistance exercise (figure regime):

Standing chess press;

Strengthening back muscles in sitting position;

Standing strengthening abduction of both shoulders;

Standing strengthening flexion of both shoulders;

Standing strengthening flexion of both forearms;

Standing strengthening extension of both forearms;

Strengthening extension of both knees in sitting position;

Strengthening flexion of both knees in sitting position;

Strengthening dorsiflexion of both ankles in sitting position.

Data collected were analyzed by using SPSS edition 13.0. Whether or not data fit the normal distribution was evaluated by using Shapiro-Wilk test and distortion and perpendicularity coefficients. Fisher's Exact Chi-Square test or Chi-Square test was utilized with the aim of comparing two or more classes qualitative variables between groups. Comparison of data collected before and after the exercise programs, which are presented as average, in and among groups, was made by using, respectively, Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance level was accepted as <0.05.

3. Results

While the average age of cases in resistance exercise group was 52.6 ± 3.5 years, average age of cases in aerobic exercise group was 52.4 ± 4.7 years. Groups were similar to one another in terms of age, educational background, marital status and, job status (P > .05). While the average age of those in resistance exercise group when they went through menopause age was 46.6 ± 4.5, it was 45.2 ± 4.1 in aerobic group. They were also similar to one another in terms of obstetrical features, first and last pregnancy ages, pregnancy, number of children, and the ages when they went through menopause (P > .05). None of the cases in both groups had any habit of exercising (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of groups.

| Demographics | Exercise groups | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance | Aerobic | ||

| (N = 18) | (N = 18) | ||

| Age, X ± SD, years | 52.6 ± 3.5 | 52.4 ± 4.7 | .751† |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Married | 14 (77.8) | 14 (77.8) | |

| Single | — | 2 (11.1) | .411‡ |

| Divorced | 4 (22.2) | 2 (11.1) | |

|

| |||

| Smoking Habitus, n (%) | |||

| Smoker | 9 (50.0) | 7 (38.9) | .502‡ |

| Non-Smoker | 9 (50.0) | 11 (61.1) | |

| Alcohol, n(%) | |||

| Drinker | 4 (22.2) | 8 (44.4) | .157‡ |

| Non-Drinker | 14 (77.8) | 10 (55.6) | |

| Exercise Habit, n (%) | |||

| Yes | — | — | NA |

| No | 18 (100.0) | 18 (100.0) | |

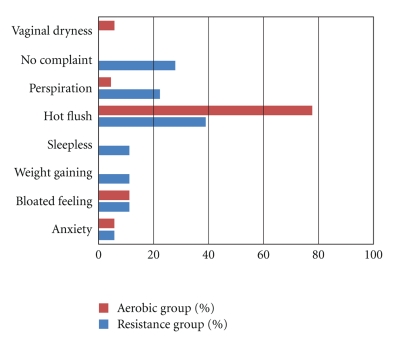

38,9% of cases in resistance exercise group and 77,8% of cases in aerobic exercise group stated that their most serious health complaint in postmenopausal period was “hot flush”. The rate of those whose most serious complaint in postmenopausal period was “perspiration” was 22,2% in resistance exercise group and 44,4% in aerobic exercise group. 27,8% of cases in resistance exercise group had no complaints pertaining to postmenopausal period (Figure 1). Prior to exercise programs, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups with respect to body mass index and waist hip ratio (P > .05). The change ratio in both BMI and Waist-Hip Ratio(WHR) values of cases in aerobic exercise group obtained before and after the exercise programs was found to be not statistically significant (P > .05). The change ratio in BMI values of cases in resistance group obtained before (26.7 ± 4.2 kg/m2) and after (26.3 ± 4.3 kg/m2) the program was found to be statistically significant (P < .05).

Figure 1.

Most serious complaints of cases in resistance and aerobic exercise groups in postmenopausal period.

Before the program began, the groups were similar in terms of triglyceride, total cholesterol, High Density Lipoprotein (HDL), and Low Density Protein (LDL) values (P > .05). In triglyceride, total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL values of cases in aerobic exercise group, no statistically significant difference was detected compared to before (P > .05). The change in triglyceride values (155.9 ± 69.5 mg/dl; 106.4 ± 56.2 mg/dl) of cases in resistance exercise group compared to before was found to be statistically significant (P < .05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lipid profile in groups.

| Into Resistance Before | Into Resistance After | P † | Into Aerobic before | Into Aerobic after | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triglyceride | 155.9 ± 69.5 | 106.4 ± 56.2 | .006 | 126.9 ± 42.3 | 126.5 ± 43.9 | .383 |

| Total Cholesterol | 238.9 ± 50.5 | 212.2 ± 42.9 | .053 | 218.7 ± 26.1 | 226.9 ± 30.2 | .210 |

| HDL | 53.4 ± 10.3 | 53.8 ± 10.9 | .419 | 58.6 ± 13.5 | 60.7 ± 17.2 | .305 |

| LDL | 153.9 ± 38.1 | 136.3 ± 37.4 | .071 | 134.3 ± 23.1 | 140.6 ± 31.0 | .286 |

Before the exercise program began, the groups were similar in terms of MRS subscale points (P > .05). In MRS “Psychological complaints” and “somatic-vegetative complaints” subscale points and total points of cases in resistance exercise group, a statistically significant decrease was found when compared to before (P < .05). Yet, in “Urogenital complaints” subscale points, no statistically significant change was found when compared to before (P > .05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

MRS scale subscale points of cases in resistance group before and after the program X ± SD, N = 18.

| Subscales of Menopausal Symptoms Evaluation Scale | Before resistance exercise program | After resistance exercise program | P Value† | Before aerobic exercise program | After aerobic exercise program | P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological complaints | 5.9 ± 3.4 | 3.5 ± 2.1 | .001 | 7.6 ± 3.8 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | .001 |

| Somatic-vegetative complaints | 6.1 ± 3.3 | 5.0 ± 3.4 | .015 | 7.2 ± 3.7 | 2.3 ± 1.6 | .001 |

| Urogenital complaints | 2.2 ± 1.7 | 1.9 ± 1.6 | .197 | 3.6 ± 2.9 | 2.7 ± 2.5 | .016 |

| Total | 14.2 ± 6.2 | 10.4 ± 4.4 | .001 | 18.3 ± 8.3 | 8.1 ± 4.9 | .001 |

†: Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

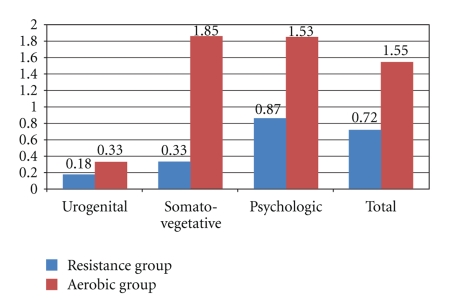

In MRS subscale points and total points of cases in aerobic exercise group, a statistically significant decrease was found when compared to before (P < .05) (Table 3). The influence quantity calculated for MRS scale subscale points of cases in aerobic exercise group was found to be higher than that of resistance exercise group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Influence Quantity calculated for changes in subscales of MRS scale. IQ: Influence Quantity.

Before the exercise program began, groups were similar in terms of SCL-90 subscale and BDI points (P > .05). In all SCL-90 R subscale points of cases in resistance exercise group except “phobic anxiety” subscale, a statistically significant decrease was found when compared to before (P < .05) (Table 4). In all SCL-90 R subscale points of cases in aerobic exercise group, a statistically significant decrease was found when compared to before (P < .05). The influence quantity calculated for changes in BDI points of resistance exercise group was found to be higher than that of aerobic exercise group (resistance IQ: 1,26; Aerobic IQ: 1,12) (Table 4).

Table 4.

SCL-90-R subscale and BDI points of Aerobic and Resistance exercise groups before and after the exercise program X ± SD, N = 18.

| SCL-90-R Subscales-BDI | Before resistance exercise program | After resistance exercise program | P Value† | IQ | Before Aerobic exercise program | After aerobic exercise program | P Value† | IQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatization | 1.06 ± 0.7 | 0.61 ± 0.5 | .001 | 0.75 | 1.09 ± 0.9 | 0.56 ± 0.5 | .001 | 0.76 |

| Anxiety | 0.61 ± 0.5 | 0.39 ± 0.4 | .001 | 0.49 | 0.71 ± 0.5 | 0.38 ± 0.4 | .001 | 0.73 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Dimension | 0.87 ± 0.6 | 0.59 ± 0.5 | .001 | 0.51 | 1.26 ± 0.7 | 0.74 ± 0.5 | .001 | 0.87 |

| Depression | 0.77 ± 0.6 | 0.49 ± 0.5 | .001 | 0.51 | 0.97 ± 0.8 | 0.56 ± 0.4 | .001 | 0.68 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.50 ± 0.4 | 0.33 ± 0.4 | .005 | 0.43 | 0.81 ± 0.6 | 0.50 ± 0.4 | .001 | 0.62 |

| Psychoticism | 0.25 ± 0.3 | 0.19 ± 0.3 | .039 | 0.20 | 0.59 ± 0.5 | 0.32 ± 0.3 | .001 | 0.68 |

| Paranoid Thoughts | 0.52 ± 0.5 | 0.41 ± 0.4 | .011 | 0.24 | 0.80 ± 0.5 | 0.45 ± 0.4 | .002 | 0.78 |

| Anger-Hostility | 0.42 ± 0.4 | 0.28 ± 0.4 | .007 | 0.35 | 0.63 ± 0.6 | 0.30 ± 0.3 | .003 | 0.73 |

| Phobic anxiety | 0.39 ± 0.5 | 0.32 ± 0.4 | .068 | 0.16 | 0.31 ± 0.4 | 0.18 ± 0.2 | .029 | 0.43 |

|

| ||||||||

| Additional Scale | 0.70 ± 0.6 | 0.55 ± 0.6 | .008 | 0.25 | 1.24 ± 0.8 | 0.55 ± 0.4 | .001 | 1.15 |

|

| ||||||||

| Average General Symptoms | 0.64 ± 0.4 | 0.43 ± 0.4 | .001 | 0.53 | 0.86 ± 0.6 | 0.44 ± 0.3 | .001 | 0.93 |

|

| ||||||||

| Beck Depression Inventory | 10.7 ± 5.8 | 5.1 ± 3.1 | .001 | 1.26 | 11.9 ± 8.5 | 4.7 ± 4.4 | .001 | 1.12 |

IQ: Influence Quantity, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, †Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Before the program began, groups were similar in terms of MENQOL scale subscale points (P > .05). In all MENQOL subscale points of cases in both groups except “Sexual Symptoms” subscale, a statistically significant decrease was found when compared to before (P < .05). The influence quantity calculated for changes in MENQOL subscale points of aerobic exercise group was found to be higher than that of resistance exercise group (Table 5). In the comparison of first and last values of exercise test parameters in aerobic exercise group cases, it was found that total test duration and workload reached had decreased statistically and significantly (P < .05) (Table 6).

Table 5.

MENQOL scale subscale points of Aerobic and Resistance exercise groups before and after the exercise program X ± SD, N = 18.

| MENQOL scale subscales | Before resistance exercise program | After resistance exercise program | P Value† | IQ | Before aerobic exercise program | After aerobic exercise program | P Value† | IQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vasomotor symptoms | 11.3 ± 5.9 | 10.5 ± 5.6 | .006 | 0.14 | 14.2 ± 5.4 | 11.3 ± 12.7 | .005 | 0.32 |

| Psychosocial symptoms | 22.6 ± 9.5 | 17.8 ± 7.5 | .002 | 0.56 | 29.3 ± 12.0 | 20.7 ± 8.8 | .001 | 0.83 |

| Physical symptoms | 55.7 ± 18.6 | 46.8 ± 17.5 | .004 | 0.49 | 64.2 ± 15.6 | 52.7 ± 13.7 | .001 | 0.78 |

| Sexual symptoms | 10.1 ± 7.0 | 10.1 ± 7.0 | 1.000 | 0 | 10.2 ± 7.9 | 9.7 ± 7.6 | .088 | 0.06 |

IQ: Influence Quantity, †: Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Table 6.

Exercise test parameters in aerobic group.

| Exercise test parameters | First test | Last test | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total test into Duration, sec. | 890.0 ± 168.8 | 1110.0 ± 224.7 | .001 |

| Workload reached, watt. | 64.4 ± 9.4 | 76.7 ± 12.5 | .001 |

| Heart rate recovery, pulse/min. | 85.8 ± 13.0 | 84.8 ± 11.2 | .432 |

| Diastolic blood pressure recovery, mmHg | 7.0 ± 1.3 | 6.8 ± 1.6 | .388 |

| Systolic blood pressure recovery, mmHg | 11.5 ± 1.9 | 11.2 ± 1.6 | .509 |

†: Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

4. Discussion

Physically active lifestyle can reduce the perceived intensity of menopausal symptoms and increase the state of being psychologically fine [15]. The fact that the medical staff dealing with women in menopausal period gets women adopt different habits and lifestyle in this critical period will be helpful in overcoming symptoms related to menopausal period. Recently it has been confirmed in the studies which evaluate the effects of exercise programs which contain aerobic and muscle strength training and exercise training programs accompanied by weight loss attempts that exercise has positive effects on the body composition of postmenopausal women [16, 17].

In the studies, it was found that short-term resistance exercise training in postmenopausal women does not make a significant change on BMI and waist hip ratio [18, 19]. In addition to the fact that in our study there was a slight decrease in BMI in both groups, this decrease in resistance exercise group reached the level of statistical significance. In terms of waist hip ratio, however, no significant change was observed in both exercise groups. It is reported that high levels of physical activity and particularly severe exercise are related to reduced body fat percentage and waist circumference [20]. It was considered that the intensity of exercise training being kept low and the duration of the training being short in aerobic exercise group might be an important reason why no positive effects of the exercise on the body composition was observed. In our study, BMI and waist hip ratio values were taken into consideration with the aim of evaluating the effects of aerobic and strength training on the body composition.

It is well known that exercise reduces the risk of the development of coronary arterial disease in menopausal women and is effective on other health problems occurring frequently in menopausal period [21]. In postmenopausal women, as LDL and triglyceride levels increase, HDL level decreases [22]. In our study, it was observed that HDL, LDL, triglyceride, and total cholesterol levels of cases in aerobic group did not change significantly. In a study, it is stated that for a significant increase in HDL level to be obtained, a moderately intense activity which contains 16–24 km run for at least 4 months is needed [23]. According to another report, one should walk 3.2 km most days of the week in order to obtain the best health benefits from the activity [24]. According to the results of a comprehensive meta analysis, an exercise training that can affect the lipid levels of the exercise should last at least 12 weeks and be arranged in an intensity that it can provide weekly energy consumption (approx. 1200 cal.) [25]. Of cases in resistance exercise training, only in triglyceride values there was a significant decrease, but in other lipid parameters no significant change was observed. In our study, the fact that the duration of training being short (8 weeks)—each aerobic training session was approximately 30 min—and the intensity of the exercise being low was considered to explain why no positive effect on lipid profiles was observed.

In the exercise test done for aerobic exercise group after the training program, total test duration with maximum heart beat rate and workload increased. It was considered that in the light of these findings, short term low-intensity exercise training might increase the cardiovascular suitability of postmenopausal women.

It is stated in various studies and compilations in Cochrane database that physical activity and the participation in exercise have some significant positive effects on symptoms related to menopause [26]. The result of our study supported the idea that regular exercise has positive effects on somatic symptoms as stated in literature. In MRS points of cases in resistance and aerobic exercise groups after the training, significant decreases were observed. These decreases showed that the intensity of somatic complaints such as hot flush, cardiac problems, sleep disorders, and muscle-joint problems decreased in both postmenopausal women. This decrease in aerobic exercise group was found to be more significant than in resistance group in terms of influence quantity. According to MRS points after the training period, psychological symptoms of both groups had improved. After the training program, no significant change was observed in MRS points of postmenopausal women in resistance exercise group in terms of urogenital complaints. Although there were significantly improvements in MRS points of cases in aerobic exercise group in terms of urogenital complaints, it was noted that its influence quantity was low. It is emphasized that use of local low-dose estrogen is effective and safe in treatment of vaginal symptoms [27]. In our study, no special treatment or suggestion was made for urogenital complaints of cases in both groups.

At the end of our study, the effect of resistance and aerobic exercise trainings on menopausal symptoms was analyzed in general terms on the basis of changes in MRS. It was found that positive effects of aerobic exercise on menopausal symptoms were superior in terms of influence quantity.

It is emphasized that menopausal symptoms affect the quality of life in connection with their duration and intensity. Moriyama et al. showed that the quality of life of postmenopausal women who had bicycle training for 6 months in moderate intensity improved [28]. Ueda et al. obtained significant improvements in the quality of life after 12-week moderate aerobic exercise training [29]. In the study of Daley et al., it is stated that life scores related to health of women who had regular exercise more than 20 minutes, 3 days or more per week, in moderate intensity significantly increased when compared to those who did not [30]. MENQOL scale used in our study allows for evaluation of menopausal symptoms, associating them with the quality of life. Significant changes in all subscale points of the scale expect for sexual symptoms showed that both exercise programs increased the quality of life of the cases. It was found that aerobic exercise was slightly more effective in terms of influence quantity. It was concluded that the increase obtained in the quality of life might be parallel to improvement observed in menopausal symptoms of both groups. No studies that compare and contrast the effects of aerobic and resistance trainings on menopausal symptoms in postmenopausal women were found. However, the results we obtained support the studies that show the positive effects of exercise on the quality of life [28, 29].

In some studies it is stated that exercise has effect on psychological health of old women having appetite, weight, motivation loss, and low energy level. However, it is worth noting that the effect of exercise on health postmenopausal women is not mentioned [31, 32]. On the basis of this knowledge, psychological effects of two different exercise programs on women in postmenopausal period were analyzed in our study. Significant decreases in all subscale points of psychological symptoms scan list of cases in both groups showed the positive effects of both resistance and aerobic exercise training on psychological health of postmenopausal women. It was noted that psychological benefit observed in aerobic exercise group was slightly more evident. According to the results of epidemiologic studies, approximately 8% and 47% of women who have gone through menopause suffer from depression symptoms [33]. In a study that deals with postmenopausal women, it was shown that depression symptoms are seen more in women suffering from sleep disorders, and similarly there is a correlation between vasomotor and depression symptoms [34]. Asbury and his friends (Asbury et al.) reported that quality of life and depression level of postmenopausal women improved after 12-week aerobic exercise training [35]. The results related to depression of our study are in concordance with studies in literature. It was found that depression values of cases who had both aerobic and resistance training decreased significantly.

It was seen that both resistance and aerobic exercise training have similar positive effects on menopausal symptoms, psychological health and quality of life, however aerobic exercise is slightly more effective in terms of influence quantity. The thing that matters more than getting postmenopausal women to participate in physical activity programs is to motivate them to do regular exercise throughout their lives. It becomes difficult for women in menopausal period to accommodate themselves to exercise because of the presence of some symptoms. For the exercise to be able maintain long-term health benefits, it has to be planned depending on the needs, preferences, and limitations of women particularly in relation with musculoskeletal system and cardiovascular suitability. In this sense, an active lifestyle should be established among women in postmenopausal period and suitable exercise programs should be designed. Our results are considered to be promising for studies that will be planned in the future with the aim of evaluating the effects of different exercise trainings on postmenopausal women.

In the resistance exercise group, excluding the urogenital complaints, there were significant improvements in all subscales of Menopausal Rating Scale (MRS). In the resistance exercise group, excluding the phobic anxiety, there were significant improvements in all subscales of The Symptom Checklist. Depression levels significantly decreased in both groups. Improvements were observed in all subscales of Menopause-Specific Quality of Life questionnaire in both groups except for sexual symptoms. Resistance exercise and aerobic exercise were found to have a positive impact on menopausal symptoms, psychological health, depression and, quality of life.

References

- 1.Bernis C, Reher DS. Environmental contexts of menopause in Spain: comparative results from recent research. Menopause. 2007;14(4):777–787. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31803020ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Utian WH. Psychosocial and socioeconomic burden of vasomotor symptoms in menopause: a comprehensive review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2005;3, article 47 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindh-Åstrand L, Nedstrand E, Wyon Y, Hammar M. Vasomotor symptoms and quality of life in previously sedentary postmenopausal women randomised to physical activity or estrogen therapy. Maturitas. 2004;48(2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5122(03)00187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daley A, MacArthur C, McManus R, et al. Factors associated with the use of complementary medicine and non-pharmacological interventions in symptomatic menopausal women. Climacteric. 2006;9(5):336–346. doi: 10.1080/13697130600864074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nedstrand E, Wijma K, Wyon Y, Hammar M. Applied relaxation and oral estradiol treatment of vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2005;51(2):154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teoman N, Özcan A, Acar B. The effect of exercise on physical fitness and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2004;47(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(03)00241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinemann K, Ruebig A, Potthoff P, et al. The Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) scale: a methodological review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2004;2, article 45 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derogatis LR. SCL-90: Administration, Scoring and Procedure Manual-I for the Revised Version. Baltimore, Md, USA: Clinical Psychometrics Unit, School of Medicine, John Hopkins University; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frymoyer JW, Rosen JC, Clements J, Pope MH. Psychologic factors in low-back-pain disability. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1985;195:178–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck depression inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilditch JR, Lewis J, Peter A, et al. A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: development and psychometric properties. Maturitas. 1996;24(3):161–175. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(96)82006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis JE, Hilditch JR, Wong CJ. Further psychometric property development of the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life questionnaire and development of a modified version, MENQOL-Intervention questionnaire. Maturitas. 2005;50(3):209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colado JC, Triplett NT. Effects of a short-term resistance program using elastic bands versus weight machines for sedentary middle-aged women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2008;22(5):1441–1448. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31817ae67a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borg G. Borg’s Perceived Exertionand Pain Scales. Champaign, Ill, USA: Human Kinetics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elavsky S, McAuley E. Personality, menopausal symptoms, and physical activity outcomes in middle-aged women. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;46(2):123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Lang W, Janney C. Effect of exercise on 24-month weight loss maintenance in overweight women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(14):1550–1559. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuller LH, Kinzel LS, Pettee KK, et al. Lifestyle intervention and coronary heart disease risk factor changes over 18 months in postmenopausal women: the women on the move through activity and nutrition (WOMAN study) clinical trial. Journal of Women's Health. 2006;15(8):962–974. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bemben DA, Bemben MG. Effects of resistance exercise and body mass index on lipoprotein-lipid patterns of postmenopausal women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2000;14(1):80–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott KJ, Sale C, Cable NT. Effects of resistance training and detraining on muscle strength and blood lipid profiles in postmenopausal women. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2002;36(5):340–345. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.5.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sternfeld B, Bhat AK, Wang H, Sharp T, Quesenberry CP., Jr. Menopause, physical activity, and body composition/fat distribution in midlife women. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2005;37(7):1195–1202. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000170083.41186.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campos H, McNamara JR, Wilson PWF, Ordovas JM, Schaeffer EJ. Differences in low density lipoprotein subfractions and apolipoproteins in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1988;67(1):30–35. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-1-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Notelovitz M. Exercise, nutrition, and the coagulation effects of estrogen replacement on cardiovascular health. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 1987;14(1):121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the centers for disease control and prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273(5):402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leon AS, Sanchez OA. Response of blood lipids to exercise training alone or combined with dietary intervention. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2001;33(6):S502–S515. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daley A, MacArthur C, Mutrie N, Stokes-Lampard H. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006108.pub2. Article ID CD006108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blake J. Menopause: evidence-based practice. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;20(6):799–839. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriyama CK, Oneda B, Bernardo FR, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the effects of physical exercises and estrogen therapy on health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2008;15(4):613–618. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181605494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueda M. A 12-week structured education and exercise program improved climacteric symptoms in middle-aged women. Journal of Physiological Anthropology and Applied Human Science. 2004;23(5):143–148. doi: 10.2114/jpa.23.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daley A, MacArthur C, Stokes-Lampard H, McManus R, Wilson S, Mutrie N. Exercise participation, body mass index, and health-related quality of life in women of menopausal age. British Journal of General Practice. 2007;57(535):130–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grant S, Todd K, Aitchison TC, Kelly P, Stoddart D. The effects of a 12-week group exercise programme on physiological and psychological variables and function in overweight women. Public Health. 2004;118(1):31–42. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(03)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagey AR, Warren MP. Role of exercise and nutrition in menopause. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;51(3):627–641. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318180ba84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt PJ. Mood, depression, and reproductive hormones in the menopausal transition. American Journal of Medicine. 2005;118(12):54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bromberger JT, Meyer PM, Kravitz HM, et al. Psychologic distress and natural menopause: a multiethnic community study. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(9):1435–1442. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asbury EA, Chandrruangphen P, Collins P. The importance of continued exercise participation in quality of life and psychological well-being in previously inactive postmenopausal women: a pilot study. Menopause. 2006;13(4):561–567. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000196812.96128.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]