Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 were used with MF59 adjuvant as a candidate vaccine for a phase 1 safety and immunogenicity trial. Ten of 41 vaccinee serum samples displayed a neutralization titer of ⩾1:20 against vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-HCV pseudotype, 15 of 36 serum samples tested had a neutralization titer of ⩾1:400 against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-HCV pseudotype, and 10 of 36 serum samples tested had a neutralization titer of ⩾1:20 against cell culture-grown HCV genotype 1a. Neutralizing serum samples had increased affinity levels and displayed >2-fold higher specific activity levels to well-characterized epitopes on E1/E2, especially to the hypervariable region 1 of E2.

Chimpanzees vaccinated with recombinant hepatitis C virus (HCV) envelope glycoproteins induce high-titer antibodies and display a strong neutralizing activity [1, 2]. However, the neutralizing activity of HCV-specific antibodies is low in infected patients [3, 4]. The Saint Louis University National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit conducted a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study to determine the safety and immunogenicity of purified HCV E1/E2 glycoproteins as a vaccine with MF59 adjuvant among healthy volunteers. Antibody-mediated pseudotype neutralization and neutralization of HCV genotype 1a grown in cell culture [5, 6] were examined in characterizing the humoral immune response associated with HCV vaccination. Serum samples from vaccinees were also examined for avidity, subclass distribution, and reactivity to linear epitopes of E1 and E2.

Methods

A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study was completed after approval by the Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board. Immunizations included 4 doses of purified Chinese hamster ovarian cell-derived fulllength recombinant E1/E2 glycoproteins of HCV genotype 1a along with the MF59 adjuvant (Novartis) in 3 different volunteer groups. The volunteers in each group were vaccinated 4 times (at 0, 4, 24, and 48 weeks) with 4, 20, or 100 µg of E1/E2 per vaccine dose and MF59 adjuvant. Sixteen volunteers were vaccinated and 4 received a placebo control. Serum samples were collected from the volunteers at different time points and heat inactivated, and the nature of the antibody responses was characterized.

The avidity index of HCV E1/E2 antibodies was determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent elution assay using sodium thiocyanate as a chaotropic agent [7]. Four biotinylated peptides representing known linear B cell epitopes on E1 and E2 glycoproteins [8–11] were synthesized (AnaSpec) and used to determine the epitope-specific antibody response by enzymelinked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed for statistical analyses with the use of Prism software (version 4; GraphPad).

Pseudotypes derived from vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were generated using HCV envelope glycoproteins from genotype 1 (GenBank accession no. M62321) and were used as surrogates for virus neutralization [6]. Sulfated sialyl lipid (NMSO3) was used for the VSV-HCV pseudotype assay to inhibit any potential effect from residual uptake of parental G glycoprotein to the VSVts045 backbone. Serial dilutions of antibodies were added to a predetermined titer of VSV-HCV pseudotype (100 plaque-forming units per reaction) or HIV-HCV pseudotype (5 × 104 relative luciferase units per reaction) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C before addition to the cell monolayer. Cells were washed, and the level of infectivity was determined as described elsewhere [5, 12].

HCV genotype 1a (clone H77) was grown in immortalized human hepatocytes (IHH) as described elsewhere [6]. RNA was quantified by real-time polymerase chain reaction (Prism 7000 real-time thermocycler; ABI) with the use of HCV analytespecific reagents (ASR; Abbott). Virus growth was also measured by fluorescent focus forming assay. The neutralization of cell culture-grown HCV in the presence or absence of vaccinee serum was determined by infection of IHH. A human monoclonal antibody to HCV E2 glycoprotein (CBH5) was used as a neutralizing positive control. The assay was repeated 3 times, and the results were read independently by 2 different individuals.

Results

We examined serum samples from volunteers who completed the study to determine the neutralizing activity against HCV surrogate virus. Prevaccination serum samples from each of these volunteers displayed neutralization titers of ⩽1:5 when tested with VSV-HCV pseudotype. Ten of 41 serum samples from immunized volunteers displayed a detectable and specific neutralization activity level (⩾1:20) against VSV-HCV pseudotype at the close of the study. Five of these 41 serum samples had a titer of 1:20, and 5 had a titer of 1:40. Seven of 9 serum samples from placebo control volunteers had a titer of <1:5. The remaining 2 serum samples from placebo control volunteers exhibited a detectable neutralizing titer and were excluded. An increased dosage level for the candidate vaccine did not correlate with an increase in neutralizing antibody titers among the volunteers who received vaccination. A statistically significant number of serum samples (9 of 12) from volunteers who were vaccinated with the lowest dose of vaccine antigen (4 <g) tested positive for VSV-HCV pseudotype neutralization following vaccination.

Vaccinee serum samples were subsequently tested against HIV-HCV pseudotype and HCV grown in cell culture for neutralization. One of these 36 vaccinee serum samples that were tested had a titer of 1:1600, 5 had a titer of 1:800, and 9 had a titer of 1:400 against HIV-HCV pseudotype. Ten of 36 vaccinee serum samples tested displayed neutralization of HCV genotype 1a grown in cell culture. Two of these serum samples had a titer of 1:20, 5 had a titer of 1:40, and 3 had a titer of 1:80 with the cell culture-grown virus. Interestingly, 9 of these 10 serum samples neutralized VSV-HCV pseudotype, whereas all 10 displayed neutralizing activity against HIV-HCV pseudotype. Overall, the neutralization activity level against the HIV-HCV pseudotype was higher than that of the other 2 neutralization assays employed here, and it was observed in all vaccinee serum samples. Virus neutralization titers to HCV grown in cell culture could not be ascertained from 2 of the 36 serum samples, because their use at a lower dilution (1:10–1:20) disrupted the monolayer of IHH and titers were not clear at higher dilutions. On the other hand, serum samples from placebo control volunteers failed to neutralize surrogate virus or HCV grown in cell culture. Thus, the results suggested an agreement among the detectable neutralization activity levels with the surrogate models and virus grown in cell culture, although the titers varied (likely because of different readouts).

The antibody response to HCV E1/E2 envelope glycoproteins among serum samples from vaccinated volunteers and placebo control volunteers was primarily distributed in the immunoglobulin G1 and G2 subclass, and no difference was observed in immunoglobulin G subclass between neutralizing serum samples and nonneutralizing serum samples. The avidity index reflects the combined functional affinities of antibodies formed during a polyclonal humoral immune response and is considered to be a parameter that describes the efficacy of antibodies at eliminating or neutralizing an antigen. Vaccinee serum samples were investigated to correlate the neutralization activity level with the avidity index of antibodies to E1/E2. The avidity index was evaluated using 2 M of sodium thiocyanate, and the majority of the serum samples (33 of 41) obtained 16 weeks after the fourth vaccination dose from vaccinated volunteers displayed a high avidity index (>75). The acquisition of a high avidity index in serum samples from volunteers vaccinated with any 1 of the 3 escalating doses of immunogens indicated that antibody maturation was not correlated with the level of immunogen used. An analysis of serum samples from individuals over the time course of the study indicated that an increase in the antibody avidity index was established after the third dose of immunogen and was not affected by the dosage level of immunogen delivered during vaccination.

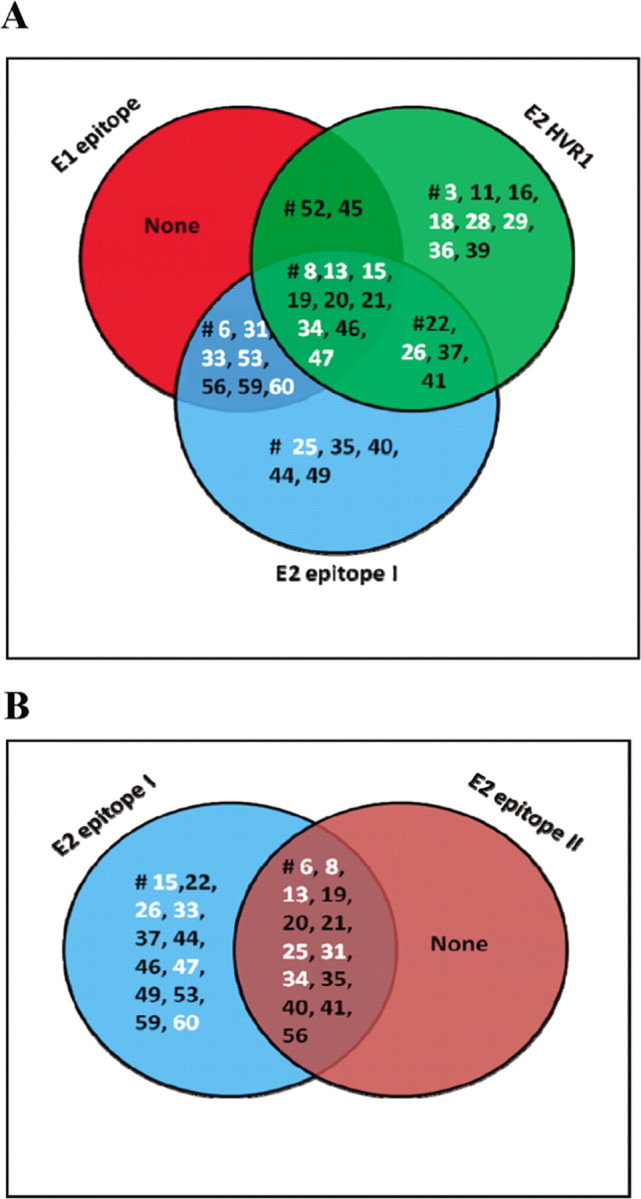

A human-derived monoclonal antibody against E1 that encompassed amino acid residues 313–327 was recently described to neutralize HCV pseudotype or virus grown in cell culture from genotypes 1a and 2a [8, 9]. Induction of a broadly crossreactive immune response to hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) of the E2 glycoprotein was suggested for the generation of protective immunity [10]. On the other hand, 2 linear antibody epitopes in the E2 protein, encompassing amino acid residues 412–426 (epitope 1) and 434–446 (epitope 2), were identified recently [11]. Epitope 1 was implicated in HCV neutralization, whereas the binding of antibodies to epitope 2 was suggested to disrupt virus neutralization associated with epitope 1 antibodies. We evaluated the reactivity levels of vaccinee serum samples at a dilution of 1:100 to the linear E1 epitope by ELISA. Fifteen of 41 serum samples exhibited a >2-fold increase in optical density to the conserved E1 epitope. Nine of these positive serum samples to the conserved E1 epitope displayed neutralization activity against an HCV pseudotype. The vaccinee serum samples were similarly examined for reactivity to the E2 epitopes. Twenty-one of the 41 serum samples from vaccinated volunteers displayed a measurable reactivity level for HVR1, with a >2-fold increase in optical density compared with a matched preimmune control sample. Eleven of the 21 HVR1-reactive serum samples displayed a detectable neutralizing activity level against the VSV-HCV pseudotype. Twenty-three of 41 vaccinee serum samples displayed reactivity with epitope 1, with an increase in optical density of >2-fold compared with serum samples from control volunteers. Of these 23 serum samples, 10 displayed neutralizing activity against VSV-HCV pseudotype. The percentage of vaccinee serum samples (43%) that displayed a positive reaction to epitope 1 was significantly higher than that observed among serum samples from patients with chronic HCV infection. In addition, 13 of 41 vaccinee serum samples reacted to epitope 2 with an optical density of >2-fold compared with preimmune or placebo control serum samples; these 13 vaccinee serum samples also displayed reactivity to epitope 1 (Figure 1). Preimmune or placebo control serum samples did not exhibit a detectable level of reactivity to the synthetic peptides used. Of these 13 positive serum samples, only 5 displayed a neutralizing titer to VSV-HCV pseudotype.

Figure 1.

Venn diagrams representing unique and shared epitope recognition of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 by serum samples from volunteers who were vaccinated with E1/E2. The reactivity level of a panel of serum samples from vaccinees was tested at a 1: 100 dilution against biotinylated peptides representing linear epitopes of E1 or E2 immobilized on an avidin-coated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate. The E1 epitope encompassing amino acid residues 313–327 (Ile-Thr-Gly-His-Arg-Met-Ala-Trp-Asp-Met-Met-Met-Asn-Trp-Ser-OH), the E2 hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) epitope encompassing amino acid residues 384–411 (Glu-Thr-His-Val-Thr-Gly-Gly-Ser-Ala-Gly-His-Thr-Val-Ser-Gly-Phe-Val-Ser-Leu-Leu-Ala-Pro-Gly-Ala-Lys-Gln-Asn-OH), the E2 epitope 1 encompassing amino acid residues 412–419 (Gln-Leu-Ile-Asn-Thr-Asn-Gly-Ser-Trp-His-Ile-Asn-Ser-Thr-Ala-OH), and the E2 epitope 2 encompassing amino acid residues 434–446 (Leu-Asn-Thr-Gly-Trp-Leu-Ala-Gly-Leu-Phe-Tyr-Gln-His-Lys-Phe-OH) were immobilized (20 ng per well) on avidin-coated ELISA plates. The plates were incubated with 1:50 dilutions of test serum samples overnight at 4°C and washed, and bound antibody was detected by adding streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase- conjugated antibody to human immunoglobulin and peroxidase substrate. The color intensity was measured by absorbance at 492 nm. Results that displayed reactivity with an increase in optical density of >2-fold compared with a matched preimmune or placebo control serum sample were considered positive. The overlapping regions represent serum samples that concomitantly recognized epitopes on E1 and E2 (A). Serum samples that recognized E2-neutralizing epitope 1 and nonneutralizing epitope 2 are also shown (B). Serum samples that displayed neutralizing activity are labeled in white.

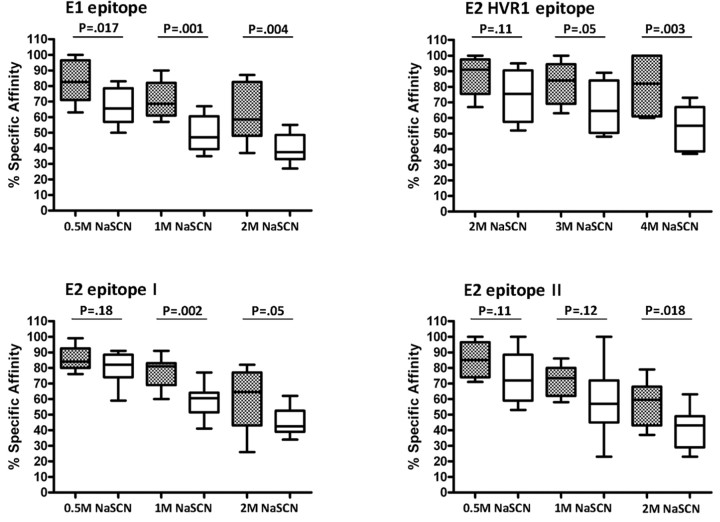

Vaccinee serum samples were characterized as neutralizing or nonneutralizing and evaluated for antibody affinity to specific epitopes. Serum samples that had the ability to neutralize HCV displayed higher epitope-specific affinity than that displayed by nonneutralizing serum samples (Figure 2). However, unlike the affinity displayed by the identified neutralizing epitopes, specific affinity for the neutralization activity that disrupted epitope 2 in the presence of up to 1 Mof sodiumthiocyanate was comparable in both groups. Interestingly, the level of antibody affinity to the HVR1 epitope was significantly higher than that to the other epitopes tested, even in the presence of up to 4 M of sodium thiocyanate. The results suggested that antibodies with a strong affinity to neutralizing epitopes are associated with E1 and E2 HVR1 and may correlate with the level of HCV neutralization.

Figure 2.

Antibody affinity to the linear epitopes of hepatitis C virus (HCV) envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 in serum samples from volunteers vaccinated with E1/E2. Neutralizing and nonneutralizing vaccinee serum samples were analyzed for affinity to synthetic peptides representing HCV E1 and E2 epitopes (hypervariable region 1 [HVR1], epitope 1, and epitope 2) immobilized on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate. Biotin-conjugated synthetic peptides were immobilized on an avidin-coated ELISA plate. Antibody affinity levels to the synthetic peptides were determined by adding individual neutralizing serum samples (gray boxes) or nonneutralizing serum samples (white boxes) at a 1:50 dilution in the presence of varying concentrations of sodium thiocyanate (NaSCN; 0.5, 1, and 2 M for E1, E2 epitope 1, and E2 epitope 2; 2, 3, and 4 M for HVR1). Bound antibody was detected with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody to human immunoglobulin and peroxidase substrate. Reactivity levels were compared in the absence of NaSCN. The resulting levels of reactivity to each of the 4 epitopes are expressed as the percentage of specific affinity and calculated as the optical density in the presence of NaSCN divided by the optical density in the absence of NaSCN, multiplied by 100. Results are shown as the mean values with standard deviations from 3 independent experiments. The boxes indicate the upper and lower quartiles, and the lines inside the boxes indicate the median values. P values were determined by the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Discussion

Our study highlights the findings that a significant number of serum samples from vaccinees display high avidity for HCV E1/E2 and approximately half of the serum samples react to the E2 HVR1. Some of the serum samples also recognized other linear epitopes on E1 and E2 envelope glycoproteins. We did not observe a statistically significant correlation between the level of neutralizing activity and the dose of the immunogen among samples from vaccinated volunteers. Our results suggest that the avidity of HCV E1/E2-specific antibodies increased after priming and boosting during the course of vaccination. Furthermore, an increase in the avidity index by 2 weeks after the fourth vaccination dose suggests a selective stimulation of high-avidity memory B cells. The neutralization activity levels of vaccinee serum samples against VSV-HCV pseudotype were also similar at the middle time point of testing (2 weeks after dose 3; data not shown), which indicates that the avidity and the ability to neutralize are established relatively quickly after vaccination. The functional importance of avidity maturation was not fully reflected in the low HCV neutralizing activity levels of the antibodies in the vaccinee serum samples.

We used 2 different HCV pseudotypes as surrogate models and HCV genotype 1a (clone H77) grown in cell culture to analyze the neutralizing activity of vaccinee serum samples. Both of the pseudotypes have advantages and disadvantages. VSV-derived pseudotypes have an easy readout of virus plaque formation and have been used extensively in our laboratory [2, 3, 5]. Some of these results were further verified with HCV grown in cell culture. Furthermore, a highly sensitive luciferase assay with the use of an HIV-derived pseudotype also exhibited neutralizing activity of serum samples from vaccinated volunteers but apparently at higher serum dilutions. The results of this investigation and those of other studies indicate a higher degree of sensitivity to antiserum-mediated inhibition of the HIV-based system compared with the VSV-based system or HCV grown in cell culture. A similar observation has been noted with the use of a severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV)-lentivirus assay in comparison with native SARS-CoV neutralization assays [13].

The lack of a strong correlation between the presence of antibodies to an E1-specific epitope, E2 HVR1, and epitope 1 in vaccinee serum samples and the neutralization of HCV indicates that the ability to generate a neutralizing response is not wholly reliant on antibodies binding to previously characterized epitopes. The generation of a neutralizing antibody response to more conserved epitopes in a vaccine preparation would be preferable, as this would limit the potential for this genotypically diverse virus to escape immune surveillance by means of selective pressure. A recombinant cell culture-grown virus derived from H77 (genotype 1a) envelope sequences replacing those of a JFH1 (genotype 2a) backbone was neutralized at a reciprocal dilution of up to 1:1600 by use of a serum sample from a patient with chronic infection (patient H), from whose sample the sequence for H77 was derived [14]. This result indicates a potential for a high neutralization titer in patients with chronic HCV infection. However, an extensive longitudinal study of neutralizing antibodies in patient H against HIV-HCV pseudotype found neutralization activity only in serum samples taken after the specific envelope gene sequence was used in that assay [15], which indicates that immune variance within a single individual could dramatically alter the antibody response to individual neutralizing epitopes. Thus, the divergence of viral proteins used in our assays may contribute to a difference in the antibody response. Distinct mechanisms of HCV entry and escape from antibody-mediated neutralization may also be the key determinants in the progression of the infection process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rajen Koshy, Leslye Johnson, Helen Quill, Robert H. Purcell, Adrian M. Di Bisceglie, Kevin Crawford, Christine Dong, Mark Wininger, and Yiu-Lian Fong for help during the study. We appreciate the help from Leonard E. Grosso for analysis of HCV genome copy number, Chen Liu for the monoclonal antibody HL1126 to HCV nonstructural protein 5A, and Steven Foung for the monoclonal antibody CBH5 to HCV glycoprotein E2.We appreciate the help from Heather Hill and Mark C.Wolff of EMMES (Rockville, MD) for statistical data analysis and Lin Cowick for preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: S.C., S.A., and M.H. were scientists at Chiron Corporation, currently owned by Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

Financial support: National Institutes of Health (grant AI068769 and contract N01-AI-25464).

References

- 1.Choo QL, Kuo G, Ralston R, et al. Vaccination of chimpanzees against infection by the hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1294–1298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagging M, Meyer K, Owens RJ, et al. Functional role of hepatitis C virus chimeric glycoproteins in the infectivity of pseudotyped virus infectivity. J Virol. 1998;72:3539–3546. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3539-3546.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lagging M, Meyer K, Westin J, et al. Neutralization of pseudotyped VSV expressing HCV E1 or E2 by sera from patients. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1165–1169. doi: 10.1086/339679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothman AL, Morishima C, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Associations among clinical, immunological, and viral quasispecies measurements in advanced chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:617–625. doi: 10.1002/hep.20581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer K, Basu A, Beyene A, et al. Coexpression of hepatitis C virus E1 and E2 chimeric envelope glycoproteins display separable ligand sensitivity and increases pseudotype infectious titer. J Virol. 2004;78:12838–12847. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12838-12847.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanda T, Basu A, Steele R, et al. Generation of infectious hepatitis C virus in immortalized human hepatocytes. J Virol. 2006;80:4633–4639. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4633-4639.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermont CL, van Dijken HH, van Limpt CJ, et al. Antibody avidity and immunoglobulin G isotype distribution following immunization with a monovalent meningococcal B outer membrane vesicle vaccine. Infect Immun. 2002;70:584–590. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.584-590.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray R, Khanna A, Lagging LM, et al. Peptide immunogen mimicry of putative E1 glycoprotein specific epitopes in hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 1994;68:4420–4426. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4420-4426.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meunier JC, Russell RS, Goossens V, et al. Isolation and characterization of broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to the E1 glycoprotein of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2008;82:966–973. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01872-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiner AJ, Geysen HM, Christopherson C, et al. Evidence for immune selection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) putative envelope glycoprotein variants: potential role in chronic HCV infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:3468–3472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang P, Zhong L, Struble EB, et al. Depletion of interfering antibodies in chronic hepatitis C patients and vaccinated chimpanzees reveals broad cross-genotype neutralizing activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7537–7541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902749106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu M, Zhang J, Flint M, et al. Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate pH-dependent cell entry of pseudotyped retroviral particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7271–7276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832180100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nie Y, Wang G, Shi X, et al. Neutralizing antibodies in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus infection. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1119–1126. doi: 10.1086/423286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottwein JM, Scheel TK, Jensen TB, et al. Development and characterization of hepatitis C virus genotype 1–7 cell culture systems: role of CD81 and scavenger receptor class B type I and effect of antiviral drugs. Hepatology. 2009;49:364–377. doi: 10.1002/hep.22673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Hahn T, Yoon JC, Alter H, et al. Hepatitis C virus continuously escapes from neutralizing antibody and T-cell responses during chronic infection in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:667–678. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]