Abstract

Objective

The Helping Older People Experience Success (HOPES) program was developed to improve psychosocial functioning and reduce long-term medical burden in older people with severe mental illness (SMI) living in the community. HOPES includes 1-year intensive skills training and health management, followed by a 1-year maintenance phase. To evaluate effects of HOPES on social skills and psychosocial functioning, a randomized controlled trial was conducted with 183 older adults with SMI (58% schizophrenia-spectrum) age 50 and older at 3 sites who were assigned to HOPES or treatment as usual (TAU) with blinded follow-up assessments at baseline and 1- and 2-year follow-up.

Results

Retention in the HOPES program was high (80%). Intent-to-treat analyses showed significant improvements for older adults assigned to HOPES compared to TAU in performance measures of social skill, psychosocial and community functioning, negative symptoms, and self-efficacy, with effect sizes in the moderate (.37-.63) range. Exploratory analyses indicated that men improved more than women in the HOPES program, whereas benefit from the program was not related to psychiatric diagnosis, age, or baseline levels of cognitive functioning, psychosocial functioning, or social skill.

Conclusions

The results support the feasibility of engaging older adults with SMI in the HOPES program, an intensive psychiatric rehabilitation intervention that incorporates skills training and medical case management, and improves psychosocial functioning in this population. Further research is needed to better understand gender differences in benefit from the HOPES program.

Many individuals with severe mental illnesses (SMI) such as schizophrenia and treatment-refractory mood disorders have prominent impairments in psychosocial functioning as they age (Bartels, Mueser, & Miles, 1997; Meeks & Murrell, 1997). Poor functioning in social relationships and independent living skills, combined with growing medical comorbidity (Druss, Bradford, Rosenheck, Radford, & Krumholz, 2000) and the loss of natural supports, makes this population highly vulnerable to long-term institutionalization in nursing homes and state hospitals (Meeks et al., 1990; Semke, Fisher, Goldman, & Hirad, 1996). Most older people with SMI live in the community (Meeks et al., 1990) and want to remain there (Bartels, 2003). In addition to the loss of independence and social dislocation inherent to institutionalization, the high cost of institutional care is concerning given the rapidly growing numbers of older people with SMI (Jeste et al., 1999). There is clearly a need to improve psychosocial functioning and to better prevent or manage chronic medical conditions of older people with SMI to improve long-term outcomes and minimize institutionalization (Atkinson & Coia, 1995; Blackmon, 1990).

Substantial advances have been made in psychiatric rehabilitation for person with SMI (Corrigan, Mueser, Bond, Drake, & Solomon, 2008). However, the age-specific rehabilitative needs of older adults have been largely neglected. Patterson and colleagues (2003) developed the group-based, 24-week Functional Adaptation Skills Training (FAST) program designed to teach independent living, communication, and illness management skills. A small randomized controlled trial of FAST found that participants showed greater improvements in living skills on the UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment (UPSA) (Patterson, Moscona, McKibbin, Hughs, & Jeste, 2001) and in negative symptoms than a usual care group (Patterson et al., 2003). An adaptation of FAST for Spanish speaking older adults, PEDAL, was evaluated in a quasi-experimental study in which two mental health centers randomized to provide the program were compared to a center randomized to provide a support group (Patterson et al., 2005). PEDAL produced greater improvements on the UPSA at post-treatment, but group differences were no longer significant at 6- and 12-month follow-ups.

Granholm, McQuaid, McClure, Pedrelli, and Jeste (2002) developed a 12-week program for middle-aged and older people with schizophrenia combining social skills training with cognitive restructuring. A small randomized controlled trial (N = 15) found that program participants showed greater improvements in overall symptoms and depression than the usual care group, but paradoxically worse negative symptoms. A larger scale controlled trial (N = 76) comparing the program with usual care found that program participants improved more in insight and in leisure and transportation skills at 6 months follow-up, but did not differ in overall living skills, symptoms, or hospitalizations (Granholm et al., 2005).

These results are encouraging because they showed that older people with SMI can be engaged and retained in skills training, and that some improvements in symptoms or skills may result. However, several limitations should be noted. None of the studies evaluated social functioning (e.g., interpersonal relationships), an important focus of social skills training programs and a stated priority for many older individuals (Auslander & Jeste, 2002). Second, the studies lacked validated strategies for fostering the generalization of targeted skills to daily living, such as in vivo practice (Glynn et al., 2002) and the use of indigenous supporters (Tauber, Wallace, & Lecomte, 2000). A final limitation is the lack of attention to health concerns, despite the fact that poorly managed comorbid medical illness is a major contributor to institutionalization in aging people with SMI (Burns & Taube, 1990; Meeks et al., 1990).

To address the rehabilitation needs of older people with SMI, we developed and pilot tested a combined skills training and health management intervention (Bartels et al., 2004; Pratt, Bartels, Mueser, & Forester, 2008). This program was designed to improve functioning and reduce institutionalization by teaching social, community living, and health maintenance skills. Based on promising results of this pilot program, the Helping Older People Experience Success (HOPES) program was developed. The HOPES program consists of a one-year intensive skills training phase, followed by a one-year maintenance phase. In addition to the core skills training component, the program also provides health care management by a nurse aimed at ensuring that participants receive preventive health care and management of chronic medical conditions.

This report focuses on the two-year psychosocial outcomes of a randomized controlled trial comparing HOPES with treatment as usual (TAU). Because HOPES is aimed at teaching specific skills critical for effective psychosocial functioning, we used separate measures of each construct. Social skills were evaluated during performance-based role play tests. Psychosocial functioning was assessed based on participant interviews and clinician/informant ratings. We hypothesized that older adults receiving HOPES would show greater improvement in both social skills and psychosocial functioning. Within the domain of psychosocial functioning, we also speculated that HOPES would produce greater improvements in leisure and recreation skills because the program specifically targets this domain. We hypothesized that we would obtain stronger effects on performance measures of skill, which are more proximal to the intervention, than measures of psychosocial functioning, which are more distal. We also hypothesized that HOPES would produce greater improvements in self-efficacy, because the program was designed to teach skills to empower people to take greater care of themselves, and greater reductions in negative symptoms, because they are strongly related to psychosocial functioning (Pogue-Geile & Harrow, 1985).

Methods

A randomized controlled trial was conducted at three mental health centers comparing HOPES with TAU. Assessments were conducted at baseline, and at 1-, 2-, and 3-year follow-up.

Study Participants

Inclusion criteria were: 1) age 50 or older (based on the definition of older adult by the American Association of Retired Persons; AARP, 2004); 2) designated by the state of NH or MA as SMI, defined as a DSM-IV Axis I disorder and persistent impairment in multiple areas of functioning (e.g., work, school, self-care); 3) diagnosis of major depression, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophrenia, based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996); and 4) able and willing to provide informed consent for participation. Exclusion criteria were: 1) residing in a nursing home or other institution; 2) primary diagnosis of dementia or significant cognitive impairment as defined by Mini Mental Status Exam (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score less than 20; 3) terminal physical illness expected to cause death within one year; and 4) current substance dependence (based on administration of the substance abuse module of the SCID).

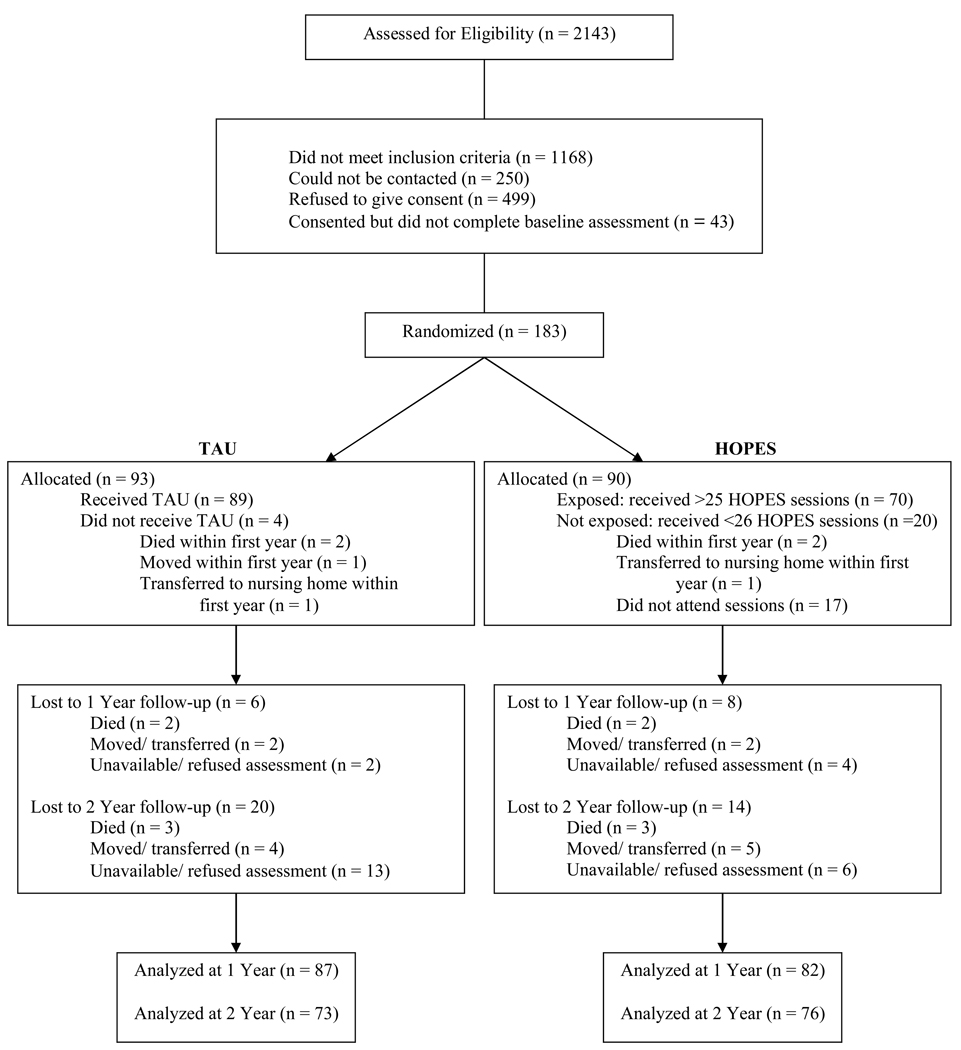

A total of 183 participants were recruited between August 2002 and August 2004 from three public mental health agencies, including two in Boston and one in NH. Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. The flow of participants through the study is summarized in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Diagnostic Characteristics of the Study Sample

| Characteristic | Total | TAU | HOPES | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 60.17 | 7.92 | 60.05 | 7.10 | 60.29 | 7.98 |

| Number of days in hospital | 20.66 | 39.56 | 21.07 | 45.05 | 20.16 | 31.14 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 77 | 42.1 | 40 | 43.0 | 37 | 41.1 |

| Female | 106 | 57.9 | 53 | 57.0 | 53 | 58.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-white | 26 | 14.2 | 15 | 16.1 | 11 | 12.2 |

| White | 157 | 85.8 | 78 | 83.90 | 79 | 87.8 |

| Latino | ||||||

| No | 171 | 93.4 | 88 | 94.6 | 83 | 92.2 |

| Yes | 12 | 6.6 | 5 | 5.4 | 7 | 7.8 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 65 | 35.5 | 34 | 36.6 | 31 | 34.4 |

| Never married | 118 | 64.5 | 59 | 63.4 | 59 | 65.6 |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than High school | 49 | 26.8 | 29 | 31.2 | 20 | 22.2 |

| High school graduate | 134 | 73.2 | 64 | 68.8 | 70 | 77.8 |

| Residential | ||||||

| Living independent | 94 | 51.4 | 49 | 52.7 | 45 | 50.0 |

| Supervised/Supported Housing | 89 | 48.6 | 44 | 47.3 | 45 | 50.0 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 51 | 27.9 | 26 | 28.0 | 25 | 27.8 |

| Schizoaffective | 52 | 28.4 | 28 | 30.1 | 24 | 26.7 |

| Depression | 44 | 24.0 | 20 | 21.5 | 24 | 26.7 |

| Bipolar | 36 | 19.7 | 19 | 20.4 | 17 | 18.9 |

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study.

Measures

Assessments were conducted by two interviewers who were trained to ensure high quality administration of all study measures, and to establish good inter-rater reliability. Training included didactic presentations, role-play practice, and observations of an experienced interviewer. Interviewers then practiced administration with older adults at a mental health center not participating in the study before performing baseline assessments. One of the co-investigators listened to audiotapes and provided weekly supervision throughout the study.

This report focuses on four domains of outcome including performance on tests of social skill, psychosocial functioning, self-efficacy, and negative symptoms. In addition, cognitive functioning was assessed to evaluate whether it predicted response to the HOPES program.

Functional skills performance

Our primary measure of community skills was the UPSA, which was developed for with older people with psychosis and functional impairments (Patterson et al., 2001) and involves a series of role plays or simulated tasks designed to assess living skills in five areas (communication, trip planning, transportation, finances, and shopping). Skill is rated based on a standardized manual, with total scores ranging from 0 to 57 and higher scores denoting better performance. The UPSA was recently recommended along with only one other multidomain measure of functioning in a review of 31 performance-based measures of living skills (Moore Palmer, Patterson, & Jeste, 2007), and has demonstrated discriminant (Mausbach et al., 2008; Patterson et al., 2001) and predictive validity, including a study in which UPSA performance predicted real world functioning in three domains (interpersonal skills, work skills and community activities as rated by an informant) (Bowie et al., 2008).

Psychosocial functioning

Our primary measure of psychosocial functioning was the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (Barker, Barron, & McFarlane, 1994), a 17-item instrument completed by an informant who is familiar with the participant’s functioning in the community. This scale uses 5-point Likert rating scales to assess social appropriateness, behavioral problems, degree of interference of physical and psychiatric symptoms, and adaptation to the mental illness. The Multnomah was usually completed by a treatment provider, but in some instances by a family member. The total score ranges from 17 to 85, with higher scores reflecting better functioning.

We also included two secondary measures of psychosocial functioning, the Social Behavior Schedule (SBS; Wykes & Sturt, 1986) and the Independent Living Skills Survey (ILSS; Wallace et al., 2000). The SBS assesses behaviors related to psychosocial functioning such as social avoidance, appropriateness of interactions, and manners. The original SBS was designed to be completed by line staff for psychiatric inpatients. We used the SBS as adapted by Schooler (1997), which contains 23 of the original 30 items. In addition to dropping items not relevant to outpatients, probe questions for participants and informants were added, and the rating scale was modified to use a consistent 1–5 scale for all items. SBS scores in this study represent a blending of self-report and informant ratings and range from 23 to 115, with higher scores reflecting worse functioning. The self-report ILSS includes 10 subscales that assess appearance and clothing, personal hygiene, care of personal possessions, food preparation, health management, leisure and recreation, money management, use of public transportation, job seeking, and job maintenance. Each of the 62 items is rated on a binary scale (no = 0, yes = 1), with higher scores reflecting better functioning. The mean score for each subscale and the total score were used in the statistical analyses. Reliability (coefficient α) of the ILSS subscales ranged from .35 to .77 (leisure = .46) and were similar to the values obtained by the authors of the scale (Wallace et al., 2000).

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was rated with the Revised Self-efficacy Scale (RSES). Designed for use with people with schizophrenia (McDermott, 1995),the RSES contains 57 statements that require respondents to rate their confidence in their ability to perform social behaviors and to manage positive and negative symptoms on a scale from 0–100, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy. Coefficient α for the RSES at baseline was .91.

Negative symptoms

Severity of negative symptoms was assessed with the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS; Andreasen, 1984). A 24-item scale evaluating negative symptoms over the prior 2 weeks, the SANS yields a total score ranging from 0 to 120, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Coefficient α for the SANS (based on the five global subscale scores) at baseline was .78. Inter-rater reliabilities for the total scores on the SANS across 18 assessments (representing three live reliability interviews for each of the six years that the study took place) were high (ICC = .84).

Cognitive functioning

Cognitive functions were assessed using several selected subtests taken from a collection of commonly used cognitive measures that were co-normed and published together as the Delis-Kaplan Executive Functioning System (DKEFS; Delis, Kaplan, & Kramer, 2001). The DKEFS includes: standard measures of verbal fluency (Letter Fluency, which is the FAS test, Category Fluency, Category Switching; Reitan & Wolfson, 1993); Color-Word Interference, which is similar to a classically used measure of attention and mental flexibility, the Stroop Test (Stroop, 1935); an expanded version of the Trails Test (Reitan & Wolfson, 1993), a test of visual conceptual and visuomotor tracking; the California Verbal Learning Test-II (Delis, Kramer, Kaplan, & Ober, 2000), a widely used measure of verbal learning and memory; a card sorting task; a modified Tower of London task; a proverbs test; a word context test, which involves defining a made-up word based on its use in a series of sentences; and a “twenty questions” test. The subtests used in this study included: the fluency measures, Color-Word Interference, the California Verbal Learning Test-II, and the Trails tests. We formed a composite cognitive score by standardizing and summing seven specific test scores that span the broad range of cognitive functions, including attention (Color-Word Interference Inhibition), verbal fluency (Letter Fluency & Category Fluency), psychomotor speed (Trails 2), memory (CVLT Trials 1–5, CVLT Long Delay Free Recall), and executive functions (Color-Word Interference Inhibition/Switching, Trails 4). Coefficient α for this composite score was .72, indicating good internal reliability.

Study Procedures

All procedures were approved by local institutional review boards. After informed consent was received and participants completed the baseline assessments, they were randomized to: 1) HOPES, or 2) TAU. Assessors were blind to treatment group. Before each follow-up interview, participants were reminded not to reveal their treatment assignment.

Randomization to HOPES or TAU within each site was stratified by diagnosis (mood disorder or schizophrenia-spectrum) and gender. Randomization was performed using a computer program and no clinical or treatment staff had access to the randomization sequence. Participants were paid for completing assessment but not for HOPES sessions.

Interventions

TAU

All participants (in both study arms) continued to receive their usual mental health services. TAU did not include medical care management or any systematic involvement of indigenous community supporters. The array of routine mental health services at all study sites included: pharmacotherapy, case management or outreach by non-nurses, individual therapy, and rehabilitation services, such as groups and psycho-education. However, the frequency and intensity of services that most participants received differed by site. In NH, the majority of participants had a case manager with whom they met for functional support weekly or at least monthly depending on impairment. Most NH participants saw a psychiatrist or nurse practitioner for medication every 6 weeks. Due to staffing constraints, a limited number of therapy groups, usually supportive psychotherapy, were offered. One skills training group and one DBT group were offered during the HOPES study, but fewer than 5 HOPES participants and fewer than 5 TAU participants were exposed to these. Staffing constraints also limited the number of HOPES and TAU participants (<25%) who received individual therapy.

Receipt of services in Boston was more variable given the array of different mental health service providers in MA. All clients received some mental health services from either North Suffolk Mental Health Association or Massachusetts Mental Health Center. Participants received pharmacotherapy every 1–6 months. Few received intensive outreach or functional support on a regular basis; however, group home residents (20% of participants) could access in-house staff support and participants living in supervised apartments (6%) could access intermittent support from staff. Few in Boston received individual therapy. A minority (30–40%) received group therapy; however, none received skills training. All study participants were taking at least one psychotropic medication, with the majority taking several, in addition to medications for physical health problems. No medication guidelines were provided as part of the study.

HOPES

HOPES includes a social rehabilitation component and a health management component delivered over a 2-year period. This report addresses the psychosocial outcomes of this intervention. The first, intensive year included weekly skills classes, twice monthly community practice trips, and monthly 1:1 meetings with a nurse. The second, maintenance year included monthly skills classes, community practice trips, and meetings with a nurse. HOPES classes were conducted using the principles of social skills training (modeling, role playing, positive and corrective feedback, home work assignments) with most of the curriculum developed specifically for older persons with SMI and some of it adapted from the Bellack et al. (2004) curriculum. The curriculum was organized into seven modules: Communicating Effectively, Making and Keeping Friends, Making the Most of Leisure Time, Healthy Living, Using Medications Effectively, and Making the Most of a Health Care Visit. Each module included 6–8 component skills, with one skill taught each week.

Skills training sessions were co-led by rehabilitation specialists (one master’s level clinician and one bachelor’s level clinician) and were conducted either at the mental health center or a local senior citizens center. Two skills training sessions were taught in a single day to accommodate older adults with limited access to transportation and difficulties with mobility, with a 90-minute morning session and a 60-minute afternoon session separated by a lunch period, which provided opportunities for informal socialization among the group members and leaders. During the intensive phase of the program, mean attendance at the 50 weekly skills classes for all participants assigned to HOPES differed across sites, with 68% attendance for the NH site, and 66% and 90% for each of the Boston sites. The best attendance was obtained at the site where clients had the lowest need for transportation assistance. During the maintenance phase, mean attendance at the 12 monthly skills classes (70%) was similar across sites.

Community practice trips were planned collaboratively by the group participants and leaders, and involved an outing to a location in which skills related to the module topic could be practiced (e.g., riding the subway or bus to practice using public transportation). During the intensive phase, mean attendance at the 26 community trips for all participants assigned to HOPES was 44%. Mean attendance at the 12 monthly community trips during the maintenance phase (55%) was somewhat better; however, we observed that it was much more challenging to engage older adult consumers in the outings than in the skills classes. Many participants avoided trips because they feared being identified as a “mental health group” in public settings. Others feared losing control of bladder or bowel functions in public. Although participants were given $5 to spend on each outing, some felt they could not “afford” the trips.

Although HOPES was provided as a two-year program, the seven HOPES modules were designed as stand-alone interventions and the program was offered on a rotating basis to allow participants to join at any time and to receive all intensive classes at the end of one calendar year. Class size typically ranged from 6–8, but as many as 12–14 were occasionally accommodated. When possible, individual sessions with one of the leaders were scheduled to make up for missed group sessions. All clients identified an indigenous supporter (e.g., family member, friend, clinician) who could help them practice targeted skills in the natural environment. Leaders had monthly contact with them to provide a summary of each skill, to discuss situations in which participants could practice the skills, and to provide suggestions for how to prompt and reinforce the use of skills. Although we did not track amount of contact between participants and their indigenous supporters, we encouraged all participants to identify someone with whom they had at least weekly contact. Many participants struggled to identify family members or friends and therefore relied on paid professionals as supporters.

HOPES is standardized in a manual and each participant was given a workbook that summarized the skill areas and included home practice assignments. Fidelity to the manual was evaluated using a fidelity scale designed for the study. Ratings on a 0–2 scale (0 = no implementation, 1 = partial implementation, 2 = full implementation) were completed based on videotapes of group sessions by the two co-investigators (Mueser and Pratt), who had expertise in skills training and who also provided weekly phone supervision in all 5 years of the study to all rehabilitation specialists and periodic live supervision at the research sites. Based on reviews of 47 videotaped sessions, the leaders at all sites demonstrated full adherence to the manual.

The health management component of HOPES was delivered by RNs and began with a medical history and evaluation of health care needs, including preventive health care. The RNs and participants then collaboratively set health-related goals for obtaining recommended preventive care and for managing medical conditions. Across all three sites, participants attended an average of 66% of the scheduled nurse sessions. During the maintenance year, monthly 1:1 meetings were held for the first 6 months, followed by an alternating schedule of monthly group and 1:1 meetings. Attendance at these meetings was 59%. The skills training leaders and RNs met weekly to coordinate the two components of the HOPES program.

Statistical Analyses

Sample size was determined by computing statistical power to detect effect sizes based on our pilot study of HOPES (Bartels et al., 2004) for three of the primary outcome measures, the SBS (ES = .78), the ILSS (ES = .63), and the health maintenance subscale of the ILSS (ES = .45). A sample size of 160 was initially established, based on an anticipated attrition rate of 20% over two years, which would yield power of 99%, 96%, and 72% for the three outcomes respectively (Borenstein & Rothstein, 1999). The planned sample size was increased to 180 to increase power to detect significant differences in outcomes.

Two tailed t-tests and χ2 analyses were used to compare the HOPES and TAU groups on demographic characteristics, psychiatric history, and outcome measures at baseline. Similar tests were used to compare men and women on the same measures at baseline, and to compare the diagnostic groups. “Exposure” to HOPES was set at participation in more than one-half of the 50 scheduled sessions during the first year, either in group or individually. There was no a priori theoretical approach to defining exposure. Instead, we examined the frequency distribution of attendance and found that 20 participants attended less than 26 sessions (M = 8.6), with 4 participants attending no sessions, and 70 participants attended more than half (M = 43.7). In order to evaluate whether clients exposed to HOPES during the first year differed from those who did not, we computed t-tests and χ2 analyses on the demographic and background characteristics, and the baseline dependent variables.

For the analysis of treatment effects, the total score for each outcome measure was the dependent measure (e.g., Multnomah). In addition, differences in the leisure subscale of the ILSS were evaluated because the HOPES program specifically targeted this domain. Treatment effects were evaluated by conducting intent-to-treat analyses on the full sample of randomized participants, regardless of exposure. Because there were no significant differences between HOPES and TAU at baseline and there were only two follow-up assessments, rather than fitting parametric curves with random effects we included the baseline as a covariate and fit baseline adjusted mean response profile models (Fitzmaurice, Laird, & Ware, 2004) using the SAS PROC MIXED procedure (SAS Institute Inc., 2006). This approach, also referred to as covariance pattern models (Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006), is similar to a traditional analysis of covariance except that it can accommodate correlated data by selecting appropriate covariance structures as well as missing data with maximum likelihood estimation (Jennrich & Schluchter, 1986). Rather than fitting models for different outcomes with possibly different covariance structures, we obtained estimates of standard error in PROC MIXED by using the “empirical” estimate option. This method is based on “sandwich estimation” (Diggle, Liang, & Zeger, 2002), and yields robust and asymptotically consistent estimates of variance and covariance regardless of the data’s actual covariance structure. For these analyses, treatment group, diagnosis, gender, time, and their interactions were included in the model, with the baseline score as a covariate, and 1-year and 2-year scores as the dependent variables. Site was included in the initial analyses but was dropped from the final models because it did not interact with treatment group or alter the main effects. Because the baseline was statistically adjusted, treatment effects were evaluated with group main effects (i.e., differences in group mean response profiles).

In order to evaluate change from baseline to the 1- and 2-year follow-ups in the measures, we performed similar analyses using SAS PROC MIXED to model time effects across all three assessments, including diagnosis, gender, and their interactions. Two-tailed statistical tests were conducted and differences were considered statistically significant based on a p-value of .05 or less. Effect sizes were computed using Cohen’s d and employing an ANCOVA approach to adjust for covariates and the correlation between baseline and the outcome year.

Results

Participants assigned to the HOPES program did not differ significantly from those assigned to TAU on any demographic, diagnostic, or baseline measures.

Gender and Diagnostic Differences at Baseline

Comparisons of male and female participants indicated several significant demographic and diagnostic differences. Women (M = 61.25, N = 106, SD = 8.39) were significantly older than men (M = 58.67, N = 77, SD = 7.00), t(181) = 2.196, p = .029, were less likely to be Latino (3/103 or 3% vs. 9/68 or 12%, respectively), χ2(1) = 5.712, p = .017, were more likely to have been married (81/106 or 77% vs. 37/77 or 48%, respectively), χ2(1) = 15.667, p = .000, were more likely to be living independently (68/106 or 64% vs. 26/77 or 34%, respectively), χ2(1) = 16.483, p = .000, and were more likely to have major depression (33/106 or 31% vs. 11/77 or 14%, respectively) or bipolar disorder (26/106 or 25% vs. 10/77 or 13%, respectively), and less likely to have schizophrenia (19/106 or 18% vs. 32/77 or 42%, respectively) or schizoaffective disorder (28/106 or 26% vs. 24/77 or 31%, respectively), χ2(3) = 17.578, p = .001. Women (M = 41.84) also performed significantly better than men (M = 38.62), t(181) = 2.179, p = .031, on the UPSA Total score, and had better independent living skills on the ILSS total (Ms = .68 vs. .62), t(181) = 3.190, p = .002, but did not differ on other outcome measures at baseline.

Several diagnostic differences were also present. The mood disorder group (M = 61.91, N = 80, SD = 8.47) was significantly older than the schizophrenia-spectrum disorder group (M = 58.81, N = 103, SD = 7.21), t(181) = 2.668, p = .008, was more likely to have been married (69/80 or 86% vs. 49/103 or 48%, respectively), χ2(1) = 29.410, p = .000, and was more likely to be living independently (54/80 or 68% vs. 40/103 or 39%, respectively), χ2(1) = 14.810, p = .000. The mood disorder group also performed better on the UPSA (Ms = 43.24 and 38.35, Ns = 80 and 103, SDs = 10.19 and 9.27, respectively), t(181) = 3.387, p = .001, and the MMAA (Ms = 8.41 and 7.34, Ns = 80 and 103, SDs = 3.49 and 3.51, respectively), t(181) = 2.056, p = .041.

Treatment Exposure and Outcome Analyses

Among the 88 participants assigned to HOPES who remained in the study during the first year, 70 (80%) were exposed to HOPES (attended 26 or more sessions), with these individuals attending an average of 84% of the 50 scheduled sessions. The 70 clients exposed to HOPES did not differ on any demographic, history, diagnostic, or outcome variables at baseline from the people who were available (i.e., did not die or move) but attended fewer than 26 sessions.

Analyses comparing the outcomes of HOPES versus TAU indicated main group effects favoring HOPES for the UPSA, Multnomah, ILSS leisure and recreation subscale, RSES, and SANS, but not the SBS, ILSS Total, the other ILSS subscales or the UPSA subscales. Table 2 summarizes the main group effects on the primary outcome measures, as well as descriptive statistics for baseline, 1- and 2-year assessments, and effect sizes.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and Treatment Group Effects for Primary Outcomes of HOPES and TAU

| Group Effect* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Condition | Base | 1 Year | 2 Year | Effect Size Baseline to Year 1 |

Effect Size Baseline to Year 2 |

df | F | P |

| Performance Skills | |||||||||

| UPSA Total | HOPES | 41.32 (9.84) | 43.91 (7.82) | 44.51 (7.82) | 0.51 | 0.45 | 1,159 | 4.94 | < .05 |

| TAU | 39.68 (10.06) | 40.53 (9.00) | 41.11 (10.67) | ||||||

| Psychosocial Functioning | |||||||||

| Multnomah Community Ability Scale | HOPES | 62.22 (8.67) | 63.92 (7.65) | 64.26 (8.67) | 0.44 | 0.37 | 1,150 | 6.17 | < .05 |

| TAU | 62.73 (8.67) | 60.86 (8.50) | 61.88 (9.01) | ||||||

| Social Behavior Schedule | HOPES | 51.42 (8.94) | 49.30 (8.54) | 46.74 (8.41) | −0.20 | −0.29 | 1,161 | 2.85 | NS |

| TAU | 51.17 (7.97) | 50.75 (9.23) | 49.14 (9.58) | ||||||

| ILSS Total | HOPES | 0.66 (0.10) | 0.68 (0.09) | 0.68 (0.11) | 0.25 | 0.32 | 1,164 | 2.28 | NS |

| TAU | 0.65 (0.11) | 0.66 (0.11) | 0.65 (0.12) | ||||||

| ILSS Leisure & Recreation | HOPES | 0.40 (0.15) | 0.45 (0.17) | 0.43 (0.14) | 0.62 | 0.63 | 1,158 | 8.78 | < .01 |

| TAU | 0.38 (0.15) | 0.37 (0.16) | 0.35 (0.14) | ||||||

| Symptoms | |||||||||

| SANS | HOPES | 2.42 (0.54) | 2.29 (0.49) | 2.26 (0.55) | −0.54 | −0.53 | 1,154 | 4.59 | < .05 |

| TAU | 2.50 (0.54) | 2.51 (0.57) | 2.52 (0.65) | ||||||

| Self-efficacy | |||||||||

| Revised Self-efficacy Scale | HOPES | 66.24 (19.16) | 71.35 (17.70) | 71.46 (16.37) | 0.24 | 0.01 | 1,155 | 6.54 | < .05 |

| TAU | 68.99 (18.61) | 68.76 (17.74) | 71.33 (18.49) | ||||||

Group effects based on mixed effects linear models with baseline as covariate, and with time, treatment group, diagnosis, gender, and their interactions as fixed effects. Degrees of freedom vary across analyses due to missing data.

Abbreviations: HOPES- Helping Older People Experience Success program, ILSS- Independent Living Skills Survey, SANS- Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, TAU- Treatment as Usual, UPSA- University of California at San Diego Performance - based Skills Assessment.

The analyses also indicated interactions for the SBS and ILSS between treatment group and gender, F (1, 161) = 5.24, p < .05 and F (1, 160) = 5.37, p < .05. For the SBS, women in HOPES (Ms = 51.15, 49.49, 46.65) and TAU (Ms = 49.87, 48.87, 45.85) improved from baseline, whereas for the men only those in HOPES improved (Ms = 51.81, 49.00, 46.90) but not men in TAU (Ms = 52.9, 53.38, 52.62). For the ILSS, men functioned worse at baseline and improved more over time in HOPES (Ms = .63, .67, .67) but not TAU (Ms = .63. .62, .62), whereas women in both HOPES (Ms = .68, .69, .69) and TAU (Ms = .67, .69, .69) were stable over time. Finally, there was one significant interaction between group and diagnosis for the ILSS, F (1, 160) = 4.69, p < .05, indicating that the mood disorder group benefited more from HOPES than the schizophrenia group.

The analyses of time effects indicated significant improvements over time in most of the outcomes, including the SBS, F(2, 319) = 9.94, p = .0000, ILSS Total, F(2, 306) = 2.96, p = .0534, UPSA Total, F(2, 306) = 5.86, p = .0032, and self-efficacy, F(2, 293) = 5.26, p = .0057, but not the ILSS Leisure, or the SANS.

Exploratory Analyses of Subgroup Treatment Responders

Because the analyses described above indicated a consistent pattern of modest beneficial effects favoring the HOPES program, exploratory analyses were conducted to evaluate whether subgroups of participants could be identified who benefited more strongly from the program. We identified six factors that we speculated could be related to differential response, based on either theory or prior research: gender, diagnosis (schizophrenia-schizoaffective vs. mood disorder), cognitive functioning, age (< 60 vs. >60), level of psychosocial functioning, and level of social skill. Gender was selected because some research has found then men with schizophrenia benefit more from skills training than women (Mueser, Levine, Bellack, Douglas, & Brady, 1990). The preponderance of research on social skills training has focused on schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, raising the question of whether HOPES would be more effective for these disorders than mood disorders. Cognitive functioning was examined because prior research has shown that greater cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is associated with reduced skills acquisition in social skills training (Mueser, Bellack, Douglas, & Wade, 1991; Smith, Hull, Romanelli, Fertuck, & Weiss, 1999). As people age, cognitive decline, physical infirmities, and health problems have the potential to reduce response to learning-based interventions. Finally, level of psychosocial functioning and social skill were explored because those with higher functioning or better skill have a more limited range of potential improvement from treatment than those with lower functioning or skill.

Each of the six variables was dichotomized into subgroups. For cognitive functioning, we divided the sample into low or high functioning based on the mean cognitive composite score. For psychosocial functioning, we formed a composite functioning score by standardizing the total scores of the Multnomah, SBS, ILSS, and SANS (reversing the signs of the SBS and SANS so that higher scores reflect better functioning), and then computing the average score across the four scales. Coefficient α for this composite was .73 indicating good internal reliability. Low and high subgroups were formed based on the mean psychosocial functioning composite score for each subgroup, and analyses were performed on the outcome measures as described above. For social skill, high and low groups were based on a median split of the UPSA Total score. Effect sizes for HOPES at 2 years for each subgroup were visually inspected to explore consistent patterns favoring one subgroup over the other. To maximize sample size for the subgroup comparisons, effect sizes for the first year assessment were used for participants who were missing from the second year assessment.

Table 3 summarizes the treatment effect sizes within each of the subgroups. Only gender was consistently related to different effect sizes, with men benefiting more than women on all seven outcomes. Descriptive statistics and time analyses for the male participants in HOPES compared to TAU are summarized in Table 4.

Table 3.

Effect Sizes for HOPES Program Compared to TAU for Different Subgroups of Clients

| Subgroup Variable | Outcome | Variable | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size |

Multnomah | SANS | SBS | ILSS Total |

ILSS Leisure |

Self- Efficacy |

UPSA Total |

||

| Gender: | |||||||||

| Male | 71 | 0.67 | −0.70 | −0.71 | 0.42 | 0.78 | 0.37 | 0.69 | |

| Female | 99 | 0.14 | −0.30 | 0.19 | −0.11 | 0.31 | −0.18 | 0.29 | |

| Diagnosis: | |||||||||

| Schizophrenia-Schizoaffective | 98 | 0.25 | −0.26 | −0.18 | −0.11 | 0.56 | −0.03 | 0.54 | |

| Mood Disorder | 73 | 0.53 | −0.82 | −0.20 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.42 | |

| Age: | |||||||||

| Younger (< 60 ) | 95 | 0.20 | −0.26 | −0.15 | 0.24 | 0.76 | 0.15 | 0.37 | |

| Older ( > 60 ) | 75 | 0.56 | −0.71 | −0.23 | 0.18 | 0.13 | −0.06 | 0.59 | |

| Cognitive Functioning: | |||||||||

| High | 85 | 0.31 | −0.39 | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.36 | −0.28 | 0.22 | |

| Low | 86 | 0.26 | −0.42 | −0.20 | 0.11 | 0.57 | 0.27 | 0.41 | |

| Psychosocial Functioning: | |||||||||

| High | 90 | 0.34 | −0.59 | −0.49 | 0.17 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.21 | |

| Low | 81 | 0.32 | −0.34 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.54 | 0.26 | −0.07 | |

| Social Skill: | |||||||||

| High | 94 | 0.15 | −0.46 | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.29 | −0.11 | 0.20 | |

| Low | 76 | 0.35 | −0.24 | −0.08 | −0.04 | 0.69 | 0.18 | 0.33 |

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics and Treatment Group Effects for Primary Outcomes of Male Participants (N = 77) in HOPES Program or TAU at Baseline, 1-Year, and 2-Years

| Group Effect* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Condition | Base | 1 Year | 2 Year | df | F | P |

| Performance Skills | |||||||

| UPSA Total | HOPES | 39.57(8.94) | 42.62(8.54) | 42.86(7.71) | 1,66 | 4.33 | 0.0412 |

| TAU | 37.75(9.29) | 37.13(9.52) | 38.86(9.64) | ||||

| Psychosocial Functioning | |||||||

| Multnomah Community Ability Scale | HOPES | 3.74(0.46) | 3.80(0.43) | 3.83(0.42) | 1,60 | 4.20 | 0.0448 |

| TAU | 3.70(0.53) | 3.52(0.48) | 3.50(0.57) | ||||

| Social Behavior Schedule | HOPES | 51.81(8.77) | 49.00(7.41) | 46.90(8.10) | 1,66 | 7.62 | 0.0075 |

| TAU | 52.90(7.76) | 53.39(8.72) | 52.62(9.74) | ||||

| ILSS Total | HOPES | 0.63(0.09) | 0.67(0.11) | 0.67(0.11) | 1,66 | 5.92 | 0.0176 |

| TAU | 0.63(0.11) | 0.62(0.13) | 0.62(0.12) | ||||

| ILSS Leisure & Recreation | HOPES | 0.38(0.17) | 0.46(0.19) | 0.43(0.16) | 1,64 | 5.52 | 0.0219 |

| TAU | 0.34(0.13) | 0.32(0.15) | 0.34(0.13) | ||||

| Symptoms | |||||||

| SANS Total | HOPES | 2.44(0.56) | 2.34(0.56 | 2.40(0.57) | 1,64 | 3.05 | 0.0854 |

| TAU | 2.60(0.50) | 2.72(0.59) | 2.69(0.50) | ||||

| Self-efficacy | |||||||

| Revised Self-efficacy Scale | HOPES | 67.32(20.63) | 74.73(19.06) | 1,65 | 6.13 | 0.0159 | |

| TAU | 65.83(19.48) | 67.93(20.75) | |||||

Group effects based on mixed effects linear model with baseline as covariate, and with time, treatment group, diagnosis, and their interactions as fixed effects.

Abbreviations: HOPES- Helping Older People Experience Success program, ILSS- Independent Living Skills Survey, SANS- Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, TAU- Treatment as Usual, UPSA- University of California at San Diago Performance - based Skills Assessment.

Discussion

As hypothesized, participants in HOPES showed significantly greater improvement across many of the psychosocial outcomes. Specifically, HOPES participants improved more in social skills, community functioning, negative symptoms, self-efficacy, and leisure and recreation. The improved social skill of the HOPES participants and the greater reduction in negative symptoms are consistent with a smaller trial of social skills training with older persons with psychosis (Patterson et al., 2003). Similarly, improved leisure functioning is consistent with a prior study evaluating combined social skills training and cognitive restructuring in middle aged-older adults (Granholm et al., 2005). This study extends prior research by demonstrating these effects in a mixed sample of older adults with schizophrenia-spectrum and major mood disorders, and by showing effects on a broad measure of community functioning. These findings confirm that psychosocial rehabilitation can benefit older adults with SMI who have long-standing impairments in community functioning.

Participants in HOPES did not differ from those in TAU on any of the independent living subscales of the ILSS other than the leisure and recreation subscale. The lack of differences in these areas may reflect the limited attention to these skill areas in the HOPES program. While one six-week module focused on leisure and recreation skills, only one or two sessions were spent on transportation, money management, and food preparation, and none addressed work, personal hygiene, or home maintenance. Furthermore, while two HOPES modules addressed health self-management, their focus was on healthy living (e.g., sleep habits, diet and exercise) and effective skills for interacting with health care providers. In contrast, the ILSS health maintenance subscale reflects such areas as self-reported medication adherence, safe cigarette smoking, and knowledge about insurance for medical benefits.

Participants in HOPES demonstrated significantly greater improvements in negative symptoms. These findings are consistent with those reported by Patterson and colleagues (2003) in their skills training program for older persons with schizophrenia, although similar effects were not found in Granholm et al’s (2005) combined skills training and cognitive behavioral intervention. Negative symptoms are strongly related to social skill and psychosocial functioning (Mueser, Douglas, Bellack, & Morrison, 1991; Pogue-Geile & Harrow, 1985), including in older people with schizophrenia (McGurk et al., 2000). Skills training has been shown to improve negative symptoms in other studies of schizophrenia, with a recent meta-analysis reporting an effect size of .40 in controlled studies (Kurtz & Mueser, 2008). The effect size of .53 at two years in this study was slightly higher, although the sample was diagnostically heterogeneous. The findings suggest that skills training may help address the challenging problem of negative symptoms (Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter, & Marder, 2006) both in older persons with schizophrenia, as well as those with severe mood disorders.

HOPES had a significant impact on self-efficacy during the first year, although by the second year participants who had received TAU had improved and the groups were no longer different. This improvement in the TAU group is puzzling, considering that no specific social rehabilitation services were provided to target this domain. Self-efficacy has been hypothesized to contribute to psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia (Liberman et al., 1986). However, one study found that self-efficacy did not mediate the relationship between negative symptoms and functioning, but rather negative symptoms mediated the relationship between self-efficacy and functioning (Pratt et al., 2005). The present findings are consistent with that mediation analysis because both participants in HOPES and TAU improved in self-efficacy, but only those in HOPES improved in both negative symptoms and psychosocial functioning.

Our findings provide some support for our hypothesis that HOPES would have stronger effects on performance-based measures of skills training than community functioning. Effect sizes for the UPSA were stronger at both one (.51) and two (.45) years than the corresponding effect sizes for overall functioning measured on the Multnomah (.44, 37), the SBS (−.20, −.29), or the ILSS (.25, .32). Interestingly, this same hypothesis was not supported in the recent meta-analysis of social skills training for schizophrenia, which found the same magnitude of effect sizes (.52) for both measures of skill performance and community functioning (Kurtz & Mueser, 2008). Perhaps factors other than skills play a role in improving community functioning, such as instilling hope and providing encouragement to pursue social and related goals.

The heterogeneous diagnostic composition of our study sample is representative of persons with SMI commonly served by public sector mental health service providers. Thus, results from this study are likely to generalize to populations, services, and usual care providers that commonly provide services to a broad range of persons with SMI, rather than diagnosis-specific services. Although there was one significant diagnosis by treatment group interaction, the lack of other such interactions, combined with moderately strong statistical power, suggests that HOPES was equally beneficial to participants with both mood and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, and thus may be applicable to the broad population of older persons with SMI.

The impact of HOPES on functioning was significant, with most effect sizes in the moderate range. This is comparable to the impact of social skills training on functioning for younger people with schizophrenia (Kurtz & Mueser, 2008), and other psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia mainly evaluated with younger individuals, including cognitive remediation (McGurk, Twamley, Sitzer, McHugo, & Mueser, 2007) and cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychosis (Wykes, Steel, Everitt, & Tarrier, 2008). However, the clinical significance of the observed improvements in functioning is difficult to determine. All of the participants had SMI, and therefore remission of mental illness or elimination of functional impairment was not an anticipated effect of treatment. A 2-point change on the Multnomah is relatively small considering the range of possible scores between 17 and 85, and could correspond to an improvement on just one of the 17 items. Nevertheless, significant changes were observed in some clients who participated in HOPES. For example, one man with schizophrenia who lived in a group home and was socially isolated before HOPES spent began to socialize with others and made several friends with whom he played chess regularly. One woman in HOPES with bipolar disorder who lived with her daughter and was extremely dependent upon her for basic social and living needs moved out into her own apartment, learned how to budget and use public transportation, and became actively involved in her local senior citizens center. These gains were unique and important to each individual, yet are not easily captured with the currently available measures of psychosocial functioning.

In order to explore whether certain factors predicted differential response to HOPES we compared effect sizes at two years for subgroups based on gender, diagnosis, age, cognitive functioning, psychosocial functioning, and social skill. Only gender was consistently related to effect size across all seven outcome measures, with a median effect size for males of .69 compared to only .19 for women. Furthermore, statistical analyses evaluating gender by treatment group interactions were significant for the ILSS and SBS. Two other non-controlled studies of social skills training in younger persons with schizophrenia have reported that men fared better than women (Mueser, Levine et al., 1990; Schaub et al., 1998).

It is unclear why men appeared to benefit more from HOPES than women. Men with SMI tend to have more severe psychosocial impairment than women (Angermeyer, Kuhn, & Goldstein, 1990; Mueser, Bellack, Morrison, & Wade, 1990; Usall, Haro, Ochoa, Marquez, & Araya, 2002), and in this study men had lower functioning at baseline on some but not all measures. The better outcomes for HOPES males does not appear to be due their worse functioning and greater potential for improvement because subgroup analyses based on overall level of psychosocial functioning or social skill failed to find consistent differences in response to HOPES. Social skills training approaches for SMI may have been developed with greater attention to the needs of men than women because of their more pronounced impairments. For example, in the Kurtz and Mueser (2008) meta-analysis of social skills training, 71% of study participants were male, with an average age of 37.7 years. Another possibility is that gender differences in the social functioning of persons with SMI may have led to the development of measures that are more attuned to the characteristic impairments of men, and hence are more sensitive to change. Further research is needed to explore these and other possible explanations for the gender difference in response to the HOPES program.

HOPES was relatively intensive to implement, and the overall duration of the program was relatively long, raising the question of whether it could be abbreviated and achieve the same benefits. As previously described, HOPES included seven discrete modules, which were designed as stand-alone modules, obviating the need to provide an entire year of skills training. Future research is needed to evaluate more efficient methods for delivering psychiatric rehabilitation, as well as tailoring curriculum and teaching methods so they can be delivered to individuals who may have difficulty accessing groups.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the control group received only usual services, with no attempt to control for the non-specific effects of clinician contact. The decision to compare HOPES to TAU, rather than an “attention control” treatment, was based on the fact that there is no compelling evidence supporting any intervention for improving the community functioning of older people with SMI, suggesting that what the field needs most is a standardized program capable of making those changes. Subsequent research could dismantle the intervention by evaluating the additive benefit of skills training to non-specific clinical contact. Another limitation was the relative lack of ethnic and racial diversity in the sample. Additional work is needed to evaluate HOPES in more diverse populations, and to explore the need for cultural adaptations, such as those developed by Patterson et al. (2005) for older Latino individuals with SMI. Finally, we have limited ability to speculate about the generalizability of the findings to the larger population of older people with SMI. Of the 725 individuals who were invited to join the study, approximately two-thirds declined. We were not able to collect any information about those individuals who declined other than their reason for declining, therefore, it is unclear whether those who chose to participate differed in any substantive, important ways from those who refused. The most frequently stated reasons for declining, among those who provided a reason (N = 309), were: 1) commitments that competed with the group day and time such as work or other mental health services (37%), unwillingness to join a group or receive additional mental health services (27%), lack of feasibility due to mobility, legal, medical, and other issues (17%), and lack of engagement in any services (14%).

These limitations notwithstanding, several strengths of the study are notable. Multiple methods were used to evaluate social skill and community functioning, including performance-based, self-report, and informant ratings, overcoming the limitations inherent in relying on a single source of data. The duration of HOPES allowed for an assessment of the sustainability of functional improvement over time. Prior skills training studies with older participants have been conducted for shorter periods and with briefer follow-up periods (Granholm et al., 2005; Patterson et al., 2003), which may partly account for their mixed results. Also, HOPES was implemented across three different treatment centers, with no evidence of differential effectiveness between sites, with a diagnostically heterogeneous sample, and with a large enough sample size to have sufficient statistical power to detect effects on community functioning. These characteristics support the potential effectiveness of HOPES in different settings serving the broad population of older adults with SMI. There was an excellent rate of exposure to HOPES (80%) and retention in research at the follow-up assessments. This is especially remarkable considering the age of the participants (mean age = 60), supporting the feasibility and robustness of the program for older adults. Finally, whereas other psychosocial rehabilitation programs developed for older people focus on skills training alone, the HOPES program also incorporated medical case management, responding to the critical need to address physical health of older adults with SMI.

In summary, participation in the HOPES program was associated with significantly greater improvements in social skill, community functioning, and negative symptoms compared to TAU in older persons with SMI. Social and community functioning are critical to the well-being of older people with SMI. The HOPES program has the potential to improve functioning and sustain community living in aging adults with SMI and to reduce critical risk factors associated with high rates of institutionalization and disability. The time duration of this report (two years) was too brief to detect any possible advantages of HOPES in extending community tenure, but we plan to examine this in a subsequent paper with a longer follow-up. With the rapidly growing population of older people with SMI, there is a pressing need for development and implementation of effective and age-appropriate psychosocial rehabilitation interventions aimed at improving community functioning and tenure.

5.

Appendix: CONSORT Checklist Items to include when reporting a randomized trial

|

PAPER SECTION and topic |

Item | Descriptor | Reported on Page # |

|---|---|---|---|

|

TITLE & ABSTRACT |

1 |

How participants were allocated to interventions (e.g., "random allocation", "randomized", or "randomly assigned"). |

2 |

| INTRODUCTION Background |

2 | Scientific background and explanation of rationale. | 3–6 |

| METHODS Participants |

3 |

Eligibility criteria for participants and the settings and locations where the data were collected. |

6–7 |

| Interventions | 4 |

Precise details of the interventions intended for each group and how and when they were actually administered. |

10–15 |

| Objectives | 5 | Specific objectives and hypotheses. | 6 |

| Outcomes | 6 |

Clearly defined primary and secondary outcome measures and, when applicable, any methods used to enhance the quality of measurements (e.g., multiple observations, training of assessors). |

8–10 |

| Sample size | 7 |

How sample size was determined and, when applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping rules. |

15 |

| Randomization Sequence generation |

8 |

Method used to generate the random allocation sequence, including details of any restrictions (e.g., blocking, stratification) |

10 |

| Randomization Allocation concealment |

9 |

Method used to implement the random allocation sequence (e.g., numbered containers or central telephone), clarifying whether the sequence was concealed until interventions were assigned. |

10 |

| Randomization Implementation |

10 |

Who generated the allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to their groups. |

10 |

| Blinding (masking) | 11 |

Whether or not participants, those administering the interventions, and those assessing the outcomes were blinded to group assignment. If done, how the success of blinding was evaluated. |

10 |

| Statistical methods | 12 |

Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary outcome(s); Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses. |

15–17 |

|

RESULTS Participant flow |

13 |

Flow of participants through each stage (a diagram is strongly recommended). Specifically, for each group report the numbers of participants randomly assigned, receiving intended treatment, completing the study protocol, and analyzed for the primary outcome. Describe protocol deviations from study as planned, together with reasons. |

Figure 1 |

| Recruitment | 14 | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up. | 7 |

| Baseline data | 15 |

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of each group. |

Table 2 |

| Numbers analyzed | 16 |

Number of participants (denominator) in each group included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by "intention-to-treat". State the results in absolute numbers when feasible (e.g., 10/20, not 50%). |

13–14, Figure 1 |

| Outcomes and estimation |

17 |

For each primary and secondary outcome, a summary of results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision (e.g., 95% confidence interval). |

Table 2 |

| Ancillary analyses | 18 |

Address multiplicity by reporting any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, indicating those pre-specified and those exploratory. |

None |

| Adverse events | 19 |

All important adverse events or side effects in each intervention group. |

None |

| DISCUSSION Interpretation |

20 |

Interpretation of the results, taking into account study hypotheses, sources of potential bias or imprecision and the dangers associated with multiplicity of analyses and outcomes. |

16–22 |

| Generalizability | 21 | Generalizability (external validity) of the trial findings. | 20 |

| Overall evidence | 22 |

General interpretation of the results in the context of current evidence. |

20–22 |

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by NIMH grant R01 MH62324. We wish to thank the following individuals for their assistance with this project: Kay Allen, Therese Andrews, Rachel Berman, Bruce Bird, Sarah Bishop-Horton, Alice Cassidy, Sara Castillo, Martha Curtis, Vanessa D’Anna, Meghan Driscoll, Carol Farmer, Susan Fitzpatrick, Anne Fletcher, Carol Furlong, Severina Haddad, Carol Johnson, Sarah Kelly, Lisa Kennedy, Meghan McCarthy, Gregory J. McHugo, Cynthia Meddich, Katie Merrill, Krystal Murray, Brenda Nickerson, Thomas Patterson, Reni Poulakos, Christina Riggs, Brenda Wilbert, Joanne Wojcik, Haiyi Xie, and Valerie Zelonis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/ccp

References

- AARP. Acronyms in aging: Organizations, agencies, programs, and laws. Washington, DC: AARP Research Information Center; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. Modified Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Kuhn L, Goldstein JM. Gender and the course of schizophrenia: Differences in treated outcome. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1990;16:293–307. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson JM, Coia DA. Families Coping with Schizophrenia. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Auslander L, Jeste DV. Perceptions of problems and needs for service among middle-aged and elderly outpatients with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Community Mental Health Journal. 2002;38:391–402. doi: 10.1023/a:1019808412017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker S, Barron N, McFarlane B. Multnomah Community Ability Scale: Users Manual. Portland, OR: Western Mental Health Research Center, Oregon Health Sciences University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ. Improving the United States' system of care for older adults with mental illness: findings and recommendations for the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11:486–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Forester B, Mueser KT, Miles KM, Dums AR, Pratt SI, et al. Enhanced skills training and health care management for older persons with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40:75–90. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000015219.29172.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Miles KM. Functional impairments in elderly patients with schizophrenia and major affective illness in the community: Social skills, living skills, and behavior problems. Behavior Therapy. 1997;28:43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS, Mueser KT, Gingerich S, Agresta J. Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia: A Step-by-Step Guide. Second ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmon AA. South Carolina's Elder Support Program: An alternative to hospital care for elderly persons with chronic mental illness. Adult Residential Care Journal. 1990;4(2):119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A, McClure MM, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, et al. Predicting schizophrenia patients' real-world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measures. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Taube CA. Mental health services in general medical care and in nursing homes. In: Fogel BS, Furino A, Gottlieb GL, editors. Mental Health Policy for Older Americans: Protecting Minds at Risk. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1990. pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, Solomon P. The Principles and Practice of Psychiatric Rehabilitation: An Empirical Approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Examiner’s Manual, Delis Kaplan Executive Function System. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test-Second Edition. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle P, Liang K, Zeger S. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford: Oxford Science Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:506–511. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice G, Laird N, Ware J. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn SM, Marder SR, Liberman RP, Blair K, Wirshing WC, Wirshing DA, et al. Supplementing clinic-based skills training with manual-based community support sessions: Effects on social adjustment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:829–837. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, Auslander LA, Perivoliotis D, Pedrelli P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for middle-aged and older outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:520–529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, Pedrelli P, Jeste DV. A randomized controlled pilot study of cognitive behavioral social skills training for older patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2002;53:167–169. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jennrich R, Schluchter M. Unbalanced repeated-measures models with structured covariance matrices. Biometrics. 1986;42:805–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Alexopoulus GS, Bartels SJ, Cummings JL, Gallo JL, Gottlieb GL, et al. Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health: Research agenda for the next decade. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;556:848–858. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT, Jr, Marder SR. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:214–219. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz MM, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of controlled research on social skills training for schizophrenia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:491–504. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman RP, Mueser KT, Wallace CJ, Jacobs HE, Eckman T, Massel HK. Training skills in the psychiatrically disabled: Learning coping and competence. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1986;12:631–647. doi: 10.1093/schbul/12.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Bowie CR, Harvey PD, Twamley EW, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, et al. Usefulness of the UCSD performance-based skills assessment (UPSA for predicting residential independence in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2008;42:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott BE. Development of an instrument for assessing self-efficacy in schizophrenic spectrum disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51:320–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Moriarty PJ, Harvey PD, Parrella M, White L, Davis KL. The longitudinal relationship of clinical symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive life in geriatric schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;42:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, McHugo GJ, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1791–1802. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks S, Carstensen LL, Stafford PB, Brenner LL, Weathers F, Welch R, et al. Mental health needs of the chronically mentally ill elderly. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5(2):163–171. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks S, Murrell SA. Mental illness in late life: Socioeconomic conditions, psychiatric symptoms, and adjustment of long-term sufferers. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12(2):298–308. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Bellack AS, Douglas MS, Wade JH. Prediction of social skill acquisition in schizophrenic and major affective disorder patients from memory and symptomatology. Psychiatry Research. 1991;37:281–296. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90064-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Bellack AS, Morrison RL, Wade JH. Gender, social competence, and symptomatology in schizophrenia: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:138–147. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Douglas MS, Bellack AS, Morrison RL. Assessment of enduring deficit and negative symptom subtypes in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1991;17:565–582. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Levine S, Bellack AS, Douglas MS, Brady EU. Social skills training for acute psychiatric patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1990;41:1249–1251. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Bucardo J, McKibbin CL, Mausbach BT, Moore D, Barrio C, et al. Development and pilot testing of a new psychosocial intervention for older Latinos with chronic psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005;31:922–930. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Klapow JC, Eastham JH, Heaton RK, Evans JD, Koch WL, et al. Correlates of functional status in older patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 1998;80:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, McKibbin C, Taylor M, Goldman S, Davila-Fraga W, Bucardo J, et al. Functional Adaption Skills Training (FAST): A pilot psychosocial intervention study in middle-aged and older patients with chronic psychotic disorders. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Moscona S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA): Development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001;27:235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogue-Geile MF, Harrow M. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Their longitudinal course and prognostic importance. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1985;11:427–439. doi: 10.1093/schbul/11.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt SI, Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Forester B. Helping Older People Experience Success (HOPES): An Integrated Model of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Health Care Management for Older Adults with Serious Mental Illness. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2008;11:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt SI, Mueser KT, Smith TE, Lu W. Self-efficacy and psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia: A mediational analysis. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;78:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT User's guide, Version 9.1.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schaub A, Behrendt B, Brenner HD, Mueser KT, Liberman RP. Training schizophrenic patients to manage their symptoms: Predictors of treatment response to the German Version of the Symptom Management Module. Schizophrenia Research. 1998;31:121–130. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semke J, Fisher WH, Goldman HH, Hirad A. The evolving role of the state hospital in the care and treatment of older adults: State trends, 1984 to 1993. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47(10):1082–1087. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.10.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, Hull JW, Romanelli S, Fertuck E, Weiss KA. Symptoms and neurocognition as rate limiters in skills training for psychotic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1817–1818. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reaction. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935;18:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- Tauber R, Wallace CJ, Lecomte T. Enlisting indigenous community supporters in skills training programs for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:1428–1432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.11.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA. Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;42:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usall J, Haro JM, Ochoa S, Marquez M, Araya S. Influence of gender on social outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;106:337–342. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, Tauber R, Wallace J. The Independent Living Skills Survey: A comprehensive measure of the community functioning of severely and persistently mentally ill individuals. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26:631–658. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N. Cognitive behavior therapy (CBTp) for schizophrenia: Effect sizes, clinical models and methodological rigor. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34:523–537. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes T, Sturt E. The measurement of social behaviour in psychiatric patients: An assessment of the reliability and validity of the SBS Schedule. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;148:1–11. doi: 10.1192/bjp.148.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]