Abstract

This report summarizes the findings and recommendations of an expert consensus workgroup that addressed the endangered pipeline of geriatric mental health (GMH) researchers. The workgroup was convened at the Summit on Challenges in Recruitment, Retention, and Career Development in Geriatric Mental Health Research in late 2007. Major identified challenges included attracting and developing early-career investigators into the field of GMH research; a shortfall of geriatric clinical providers and researchers; a disproportionate lack of minority researchers; inadequate mentoring and career development resources; and the loss of promising researchers during the vulnerable period of transition from research training to independent research funding. The field of GMH research has been at the forefront of developing successful programs that address these issues while spanning the spectrum of research career development. These programs serve as a model for other fields and disciplines. Core elements of these multicomponent programs include summer internships to foster early interest in GMH research (Summer Training on Aging Research Topics–Mental Health Program), research sponsorships aimed at recruitment into the field of geriatric psychiatry (Stepping Stones), research training institutes for early career development (Summer Research Institute in Geriatric Psychiatry), mentored intensive programs on developing and obtaining a first research grant (Advanced Research Institute in Geriatric Psychiatry), targeted development of minority researchers (Institute for Research Minority Training on Mental Health and Aging), and a Web-based clearinghouse of mentoring seminars and resources (MedEdMentoring.org). This report discusses implications of and principles for disseminating these programs, including examples of replications in fields besides GMH research.

The “graying of America”—the growth of the oldest cohorts of the U.S. population—constitutes one of the greatest public health challenges of our generation. By the year 2030, it is predicted that approximately 20% of the U.S. population will be more than 65 years old,1 and one-fifth of that older population—some 15 million persons—will have a mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorder.2 Mental disorders threaten functional independence and quality of life in older age and are associated with poor health outcomes, excess mortality, and increased use and costs of acute and long-term care. At the same time, we are experiencing a “research recession” that threatens the next generation of researchers. These troubling trends have converged to decrease the number of grants awarded and have made obtaining a first research award increasingly difficult. To address this urgent problem, we need a concerted focus consisting of effective strategies for the recruitment, development, and retention of the next generation of scientific investigators in the field of geriatric mental health (GMH) research.

Despite a remarkable track record of development over the past two decades, GMH research is now at a crossroads. Funding for the career development of new investigators is becoming increasingly competitive, and early-career investigators are especially vulnerable. The future of research in mental health and aging and the welfare of aging Americans are in peril because of a failing “pipeline” of upcoming researchers. Our purpose in this report is to describe the findings and recommendations of a multidisciplinary summit designed to address the paucity of investigators who are entering the field of GMH research. We highlight a primary recommendation to support, sustain, and promote successful multicomponent programs that strengthen early career development in GMH research. First, we provide the context for these programs by summarizing six critical issues and related recommendations of a consensus workgroup initiated at the 2007 Summit on Challenges in Recruitment, Retention, and Career Development in Geriatric Mental Health Research, which addressed of the shortfall of new GMH researchers. Second, we describe programs developed by persons in our field that span research career development from the earliest stages of generating interest to the later stages of mentoring investigators in the procurement of independent funding. Finally, we discuss how these programs maybe promulgated or adapted to other areas beyond GMH research.

The Summit on Challenges in Recruitment, Retention, and Career Development in Geriatric Mental Health Research

In response to the need to support the development of the next generation of GMH researchers, a summit was convened and took place from November 30 to December 2, 2007, in Potomac, Maryland. Participants ranged from early-career investigators to senior research mentors. The purposes of this summit were to identify key challenges in developing and advancing early-career GMH researchers and to formulate specific recommendations for addressing those challenges. An executive planning committee invited 22 people to ensure similar representation of MDs (n = 10) and PhDs (n = 12) as well as representation by women and minority researchers, including researchers representing different content areas and in various stages of career development. All of the invited guests attended the summit. Participants included early-career investigators with National Institutes of Health (NIH) research career development (e.g., K01, K07, and K23) awards, junior faculty investigators, and senior investigators. Participants also were selected to reflect a range of academic positions, including professors ranking from assistant to full professor, center directors, an adult psychiatry residency training director, geriatric psychiatry residency training directors, a medical school associate dean, and representatives from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Participants were assigned to workgroups designed to incorporate the perspectives of early-career investigators at different stages of research career development, federal program officers administering current and evolving funding mechanisms, and directors of mentoring programs in GMH research. Workgroups generally were cochaired by both an MD and a PhD researcher, who led conference calls before the summit to define the primary issues for their group and to develop potential strategies to address these issues. At the summit, the cochairs led a discussion by a panel of their peers, which was followed by commentary from a senior investigator and discussion among the larger group of summit participants. The titles of each of the sessions and the names of the session chairs, panel members, and discussants are provided in the Appendix. The summit was funded by a grant from the NIMH Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR) program, which aims to provide information and Web-based interactive resources to support the development of researchers in GMH.

At the close of each session, two of us (S.J.B. and B.D.L.) summarized the primary recommendations, and these summaries became part of the record of the summit. The final sessions of the summit consisted of group discussions to identify consensus recommendations. All sessions were audiotaped and transcribed in their entirety. A written summary of all issues and recommendations was then distributed to the summit members for comment. A subsequent meeting to finalize the recommendations was conducted at the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP) meeting on March 15, 2008, in Orlando, Florida. For the purposes of this report, the term geriatric mental health research (or GMH research) applies to basic, clinical, health services, and translational research focusing on late-life mental disorders. Participants achieved consensus on the following key issues and specific recommendations.

Key Issues and Specific Recommendations

Issue 1: The challenge of attracting and developing early-career investigators during a research recession

Six consecutive NIH budgets without any increase have meant less funding for new awards, increased numbers of grant applications, fewer approved proposals, and longer delays from first submission to final approval for funding—in short, a research recession. The overall rate of NIH approval of research grants has decreased from 32% in 1999 to 24% in 2007.3 Because more than three-quarters of research proposals are not being funded, researchers have sought other sources of salary support (e.g., clinical work or contracts) and have considered alternative careers. Overall productivity has also decreased, with researchers needing to spend more time writing and revising grants rather than conducting research. With fewer applications being funded on first submission (12% in 2007, down from 29% in 19993), early-career investigators have been forced to further delay, or entirely abandon, entry into the workforce of independently funded investigators. Accordingly, the average age at which a researcher receives his or her first major NIH-funded research grant (i.e., R01) has risen from 39 years old in 1990 to 43 years old in 2007.3 Further compounding the impact of this four-year delay is the unprecedented burden of student loans that come due soon after completion of undergraduate and graduate degrees.

Academic departments across the country have downsized as fewer grants are being awarded, and grant applications frequently require multiple submissions before funding is awarded. Research infrastructure support has been further eroded as established centers are experiencing greater difficulty in sustaining long-term funding, and fewer new centers are being funded. Over the past several years, early-career-development awards have witnessed a decrease from 10% to 8.6% of NIMH-funded grants.4 At the same time, the pharmaceutical industry has manifested less capacity and less willingness to invest in research on psychiatric treatments targeting the elderly that is conducted by academic institutions, and, more recently, philanthropic foundations have experienced a declining capacity to invest in research and service demonstrations because of diminished financial resources in the current economic recession.

Federal funding has not made the specific area of research on mental health and aging a high priority. For example, an analysis by the President’s Commission on Mental Health documented that the proportion of NIMH funding dedicated to grants for research on aging actually decreased from 8% in 1995 to 6% in 2000.5 More recently, the 2008 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, “Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce,”1 documented an emerging workforce crisis associated with the rapidly growing geriatric population and a similar failure to highly prioritize research on and evaluation of the health issues of aging persons. Less than 2% of Medicare’s $2 billion operations budget is spent on research, demonstration, and evaluation.1 Among the IOM’s recommendations is a call for greater support for research into new models of care for older adults that are aimed at improving the effectiveness and efficiency of health care in the context of skyrocketing annual Medicare expenditures. Overall, the aggregate of these disturbing trends creates the conditions for a “perfect storm” that threatens to diminish the future of a field that depends on a steady stream of early-career investigators and innovative research programs. The larger context of the current research recession presents the unique challenge of identifying mechanisms that will be successful in ensuring the development of future leaders in the field of GMH research.

Specific recommendations

Support and expand the program for federally funded career development awards

During this time of increasingly competitive research funding, research career development awards (i.e., “K grant” awards from the NIH) are essential to preserving the pipeline that will supply the next generation of researchers.

Support and expand the NIH Loan Repayment Program

The burden of undergraduate and graduate student loans is identified as a major threat to the survival of early-career investigators, especially during a time of diminishing grant support. The NIH Loan Repayment Program6 offers a highly valued resource that helps to offset the substantial financial burdens of graduate and undergraduate student loans that undermine the capacity of promising early-career investigators to remain in research rather than leaving to pursue more lucrative clinical or other careers.

Increase funding for postdoctoral programs offering two to three years of sponsored support to qualified persons in GMH research

Innovative approaches to pooling and virtually connecting different research sites can help overcome the research recession while also improving access to mentors and career development. For example, a multisite Postdoctoral Training Program in Geriatric Mental Health Services Research (funded via the NIH T32 institutional training grant program) links participants at Dartmouth, Cornell, and the University of Washington through biweekly, Web-based research presentations.7 These presentations are led by the trainees, in consultation with cross-site faculty and other trainees, to enhance the effectiveness and breadth of the training experience.

Maintain support for centers that emphasize mentored research opportunities for early-career investigators

The Advanced Centers for Interventions and Services Research program that is funded by NIMH has provided fertile settings for launching and supporting young investigators through research training, infrastructure, pilot studies, and salary support. More recently, the NIMH strategic plan has identified translational research as a priority area for future development.8 Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSAs) support the development of linkages between basic science and research on clinical interventions and services to bring together seemingly unrelated disciplines spanning bench to bedside to population research.9 Institutional career development awards (K12 grant awards), which are a component of the CTSA, should be encouraged to consider a life-span approach, including interdisciplinary research training pertaining to mental health and aging.

Issue 2: A shortfall of clinical providers with expertise in geriatrics and the potential to become future researchers

The recruitment of promising young investigators to careers in GMH research is made especially difficult by a lack of graduates in health care professions who have advanced training in geriatrics, including geriatric medicine, psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Recent trends clearly underscore the fact that training programs are experiencing increasing difficulty in recruiting applicants. For example, in 2001, 39% of geriatric psychiatry fellowship slots went unfilled, and this vacancy rate has continued to grow, to 52% in 2006.10

Specific recommendations

Support the Geriatrics Loan Forgiveness Act

The summit recommended supporting the Geriatrics Loan Forgiveness Act of 2009 that amends the Public Health Services Act to designate geriatric health care training, including GMH professions (e.g., psychiatry, psychology, and social work) and medical geriatrics, as eligible for the National Health Service Corps Loan Repayment Program.11 This step would allow each year of fellowship training in geriatric medicine or geriatric psychiatry to be treated as a year of obligated service, which would forgive the debt incurred by medical students for each year of advanced training that is required to obtain a certificate of added qualifications in geriatric medicine or psychiatry.

Support the recommendations for recruitment and retention of geriatric health care professionals described by the 2008 IOM report

Recommendations of the IOM report1 included enhancing financial incentives and reimbursement for practitioners with certification of expertise in geriatrics. They also include the institution of programs for loan forgiveness, scholarships, and direct financial incentives for professionals who become geriatric specialists.

Issue 3: An unmet need for research on ethnic minority elderly and on the scarcity of minority early-career investigators

Increasing the number of minority investigators and those from other underrepresented groups is crucial to the development of a diverse body of researchers that reflects the larger population. Minority elderly make up a growing segment of the older adult population in the United States. The proportion of nonwhite Americans at least 65 years old has been projected to increase to 36% by the year 2050 (from 16% in 2000).12 Minority elderly are disproportionately affected by health disparities and economic challenges, yet little research focuses on this high-risk group.

Specific recommendations

Support and enhance existing mechanisms that specifically promote diversity in research on aging and GMH

Racial-ethnic minorities are underrepresented among the mental health research workforce. Efforts to increase the number of minority early-career investigators (i.e., minority supplements, mentored minority research training awards, and postdoctoral training programs aimed at minority groups) are an urgent priority for developing researchers who are likely to have a particular commitment to addressing health care disparities.13

Establish a national mental health research mentoring program devoted to training racial-ethnic minority investigators in GMH research

Consistent with the recommendations of the National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Racial/Ethnic Diversity in Research Training and Health Disparities Research,13 programs should be supported that provide national training and mentoring resources focused on advancing racial-ethnic minority investigators in GMH.

Issue 4: The loss of promising researchers during the vulnerable period of transition from research training to being an independently funded junior investigator

Junior investigators who have achieved early success by receiving research development support (e.g., NIH or Veterans Affairs [VA] career development awards or postdoctoral fellowships) are especially likely to leave research careers if they are unable to successfully transition from receiving a training award to receiving funding as an independent investigator. Junior faculty members who have achieved advanced levels of research training are a critical resource. The investment of training dollars and time spent in mentoring junior faculty must be protected by mechanisms that ensure maximum success for these faculty members in obtaining independent funding. Supporting and advancing junior investigators at the assistant and associate professor levels constitutes a critical priority.

Specific recommendations

Enhance assistive programs that are particularly crucial to supporting early-career investigators during highly vulnerable stages of development

Current measures that are critical for early research career development should be sustained and expanded. These measures include the designation of investigators’ first R01 grant awards as a priority for NIH funding; loan repayment programs; institutional center grants emphasizing the development of early-career researchers; incentives to create academic positions that entail research administration, training, or clinical roles in an investigator’s chosen research area; support for obtaining funding from diverse sources (e.g., foundation, federal, state, and local); and the development of local departmental “bridge” funding.

Remove current restrictions on career development awards that do not allow complementary funding from other federal research grants

The restriction of “K awards” to disallow complementary funding from other federal grants, such as R01 grants, presents a particular challenge at the end of the award, when an investigator must abruptly transition from having 75% to 100% of his or her salary covered by the K award to having a much smaller portion (e.g., 30%) covered by a typical R01 grant. The transition from research development awards to independent research grants would be facilitated by flexibility in allowing the researcher to exchange a portion of salary support from the K award for partial support as a coinvestigator from other grants in the last three years of the career development K award.

Issue 5: An inadequate workforce of GMH research mentors and a need for successful career development resources and strategies

The relationship between a junior investigator and a supportive and experienced senior mentor is an essential component of successful development of a research career.14 An emerging challenge is the approaching retirement of many senior investigators. Full professors in 35% of U.S. medical schools now have an average age of more than 60 years; in departments of psychiatry, this percentage is even higher.15 In addition, a progressive erosion of funding for teaching has resulted in increasing pressure to generate direct revenue and to limit unfunded activities. Despite the well-recognized value of mentoring as a critical component in the career development of junior investigators, this function is essentially an unfunded mandate. For example, the T32 postdoctoral fellowships and research career development awards (K awards) provide funding for the trainees but do not provide salary support for the mentors. Developing the next generation of mentors will require viable financial models that support time for mentoring and include a formal strategy for the teaching of mentoring skills. Currently funded research training programs should be reconfigured to support the needs of the young investigator as well as the training needs of the developing mentor.

Specific recommendations

Develop the mentoring skills of promising junior faculty who will be the next generation of GMH research mentors

National programs aimed at providing mentoring to promising early-career investigators (e.g., the Advanced Research Institute in Geriatric Psychiatry [ARI]) also provide group-based opportunities and structured tools to support the development of mentoring skills by junior faculty. In addition to adapting and implementing these approaches to develop mentoring skills, interactive Web sites aimed at career development and mentoring (e.g., MedEd Mentoring16) should be expanded and sustained.

Support and expand existing federal mechanisms and local university support for mentoring in graduate training programs

Despite broad consensus on the importance of research mentoring for developing investigators, few mechanisms other than the K24 midcareer mentoring awards exist to support protected time for research mentoring, particularly within medical school and academic health center settings. In addition to supporting and expanding limited funding for the K24 awards and related mechanisms for GMH research, departments within academic medicine should develop clear incentives and expectations and should designate protected time for research mentoring.

Summary of Findings and Recommendations From the Summit on Challenges in Recruitment, Retention, and Career Development in Geriatric Mental Health Research

Proceedings from the two-day summit and a follow-up meeting of participants identified these five issues: (1) the challenge of attracting and developing early-career investigators during the current research recession, (2) a shortfall of clinical providers with expertise in geriatrics and the potential to become researchers, (3) an unmet need for research on ethnic minority elderly and a lack of minority early-career investigators, (4) the loss of promising researchers during the vulnerable period of transition from research training to being an independently funded junior investigator, and (5) an inadequate workforce of GMH research mentors and the need for successful career development resources and strategies.

Primary recommendation: Support, sustain, and promote successful programs to help GMH researchers progress from early interest to independent funding

Specific recommendations by the participants included a variety of training and funding programs designed to support both the development of early-career investigators and the mentoring process during the most vulnerable periods in career development. The primary consensus recommendation of the group was to support, sustain, and promote the successful series of programs that have been developed in the fields of geriatric psychiatry and GMH across the continuum of research career development.

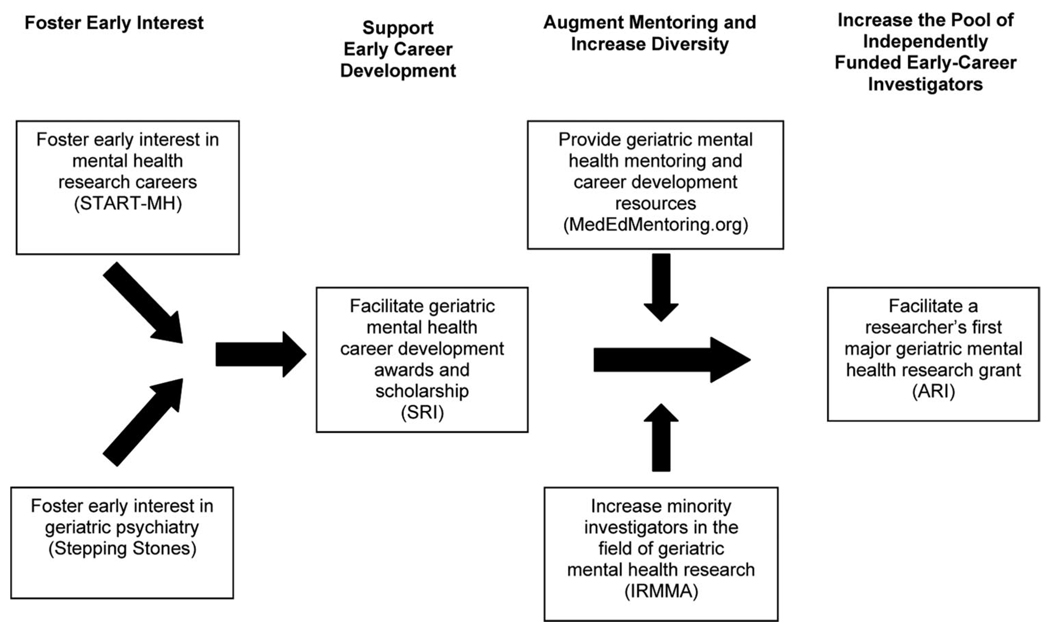

As illustrated in Figure 1, many of the key issues and challenges identified during the summit are addressed by the components of a series of programs that have been successful in engaging and supporting the development of early-career investigators in GMH research. These programs augment and support the local training environment for early-career investigators by providing resources that draw on experts from multiple centers, disciplines, and areas of research expertise in geriatrics and mental health research.

Figure 1.

Multicomponent programs supporting early-career investigator development. The text in bold indicates stages of the career development programs, and the text inside boxes refers to programs offered at each stage of professional advancement to support career development. START-MH indicates Summer Training on Aging Research Topics–Mental Health; SRI, Summer Research Institute in Geriatric Psychiatry; ARI, Advanced Research Institute in Geriatric Psychiatry; IRMMA, Institute for Research Minority Training on Mental Health and Aging. Descriptions of the START-MH, Stepping Stones, SRI, MedEdMentoring.org, IRMMA, and ARI programs can be found in Table 1.

Details of the primary recommendation

Fostering early interest in mental health research careers

Programs are needed that develop students’ interest in research at the earliest academic stages. To address this need, the Summer Training on Aging Research Topics–Mental Health (START-MH) program on mentored research was designed to promote the development of interest in mental health research careers that focus on older adults. START-MH offers aspiring researchers and undecided students the opportunity to explore careers in research while making an essential connection with a research mentor. This NIMH-funded program engages undergraduate, graduate, and medical students in a supervised research experience by matching them with a mentor and a research site, in conjunction with stipend support for a 7- to 10-week summer research internship. At the end of the research internship, students come together to present a poster at a weekend conference sponsored by the program.17 During the past six years, there have been 158 participants: 20% were undergraduate students, 41% were graduate students, and 39% were medical students. Half (49%) of the participants are from minority backgrounds. One-third (33%) have published peer-reviewed articles (20% as first author), almost half (47%) have made presentations at national research conferences, and one-third (33%) have gained special recognition by receiving research awards. On completing the summer program, 97% of the participants reported that they believed “that the field of geriatric mental health research is an excellent career choice,” and 99% reported that the internship experience positively affected their “attitude toward a career in the field of geriatric mental health research.” Unfortunately, a recent NIMH regulation precludes the awarding of stipends to undergraduate participants. According to survey responses confirming the impact of the program on enhancing participants’ interest in GMH research careers, an expansion of eligibility to include undergraduate potential investigators would further enhance opportunities to identify and foster interest among promising investigators during the critical early-development stages.

Fostering early interest in the field of geriatric psychiatry

The Stepping Stones program was developed and sponsored by the AAGP to foster interest among general psychiatry residents in pursuing fellowship training in geriatrics. Stepping Stones provides financial support to approximately 60 to 70 psychiatry residents from the United States and Canada so that they can attend the annual scientific meeting of the AAGP. In addition to attending symposia and paper sessions, fellows participate in a daylong workshop focused on clinical, teaching, and research careers in geriatric psychiatry. To date, there have been 476 participants in the Stepping Stones program. Results from a follow-up survey found that most respondents (70%) subsequently entered a geriatric psychiatry fellowship program.18 This number reflects a potentially favorable impact in fostering an interest in advanced training in geriatrics and related GMH research careers.

Supporting early development by facilitating successful career development awards and early scholarship

The Summer Research Institute in Geriatric Psychiatry (SRI) was developed in 1994 to advance early career development spanning a variety of disciplines and interest areas in GMH research. This program, funded by the NIMH, targets promising early-career individuals with MDs and PhDs who have not yet obtained federal grant support. Developed through a collaborative effort of the AAGP and the University of California at San Diego, the SRI consists of a one-week intensive program focused on research career development, grant-writing strategies, funding mechanisms, research methods, working with institutional review boards, peer review, manuscript preparation, career survival skills, and balancing life and work. In addition to attending didactic presentations, participants meet individually with faculty to discuss their research ideas, early proposals, and career development. According to follow-up surveys completed by 54% of SRI graduates, the vast majority (91%) of SRI participants have pursued full-time academic careers. More than two-thirds (68%) have been principal investigators of peer-reviewed federally funded grants: 35% of the participants have acquired a federally funded early-career-development award, 24% have acquired a major research award, and 9% have acquired both.19

Providing resources for GMH mentoring and career development

MedEdMentoring.org16 is an NIMH-funded Web site dedicated to providing resources to experienced and developing mentors and early-career investigators in GMH research. Online resources include a calendar of events, career-planning software, podcasts, presentations, medical updates, and journal articles. Links to funding and training opportunities, government resources, and additional online support are also available to investigators. The Web site provides researchers with a full range of online support and is considered to be a content clearinghouse that serves as an important tool for the cultivation of GMH investigators. It includes descriptions of career development programs (e.g., START-MH, Stepping Stones, SRI, ARI), T32 postdoctoral training programs, the NIH Loan Repayment Program, VA career development programs, and K grant programs. This Web site currently receives more than 5,000 visits each month. A related Web site, CommunityGMHResearch.org, provides monthly Webinars focused on assisting mentors and early-career investigators in developing the necessary skills and methods to successfully conduct research incorporating older adults in the community.20

Increasing training opportunities for minority early-career investigators

The Institute for Research Minority Training on Mental Health and Aging (IRMMA) was funded in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) with the goal of increasing the number of minority early-career investigators in the field. The three-year postdoctoral program included mentored research training and a master’s degree curriculum. During its five-year term, IRMMA trained 10 students from minority backgrounds: 1 Asian, 3 Latino, and 6 African American participants. Unfortunately, IRMMA was unable to obtain renewal funding. Nonetheless, it is a prime example of a program that was explicitly focused on addressing a shortfall of minority investigators in the field of GMH research. In response to this need, other programs have emphasized recruiting minority applicants. For example, approximately half of START-MH and one-quarter of SRI participants are members of ethnic minority groups.

Facilitating successful transition from K award funding to independent research funding

The ARI was developed to address the gap that is commonly experienced by promising early-career investigators between receipt of career development awards and of their first major R01 research grant. The ARI is an NIMH-funded fellowship that matches early-career investigators who have K awards or VA merit awards with a senior research mentor from another institution who has similar research interests. This process begins with an intensive research retreat that includes formal presentations by the fellow of his or her developing research proposal, in conjunction with individual meetings with the assigned mentor and other ARI faculty. Subsequently, the mentor and mentee continue to work together to revise and advance the research grant application during a two-year period through long-distance mentoring and face-to-face encounters at the annual ARI retreat and at annual scientific research meetings. To date, four cohorts of 42 participants have been trained. The success rate of ARI participants in achieving a first major federally funded research grant (71%) is almost double the average for NIMH K awardees overall (38%).21 The six programs reviewed throughout this section are presented, including descriptions and outcomes of each program, in Table 1.

Table 1.

Components and Outcomes of U.S. National Programs for Early-Career Development in Geriatric Mental Health Research*

| Objective | Program | Description | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foster early interest in mental health research |

START-MH | • Undergraduate (20%), graduate (41%), and medical (39%) students matched with a research mentor and site for 7- to 10-week geriatric mental health research internship |

• 158 participants, 49% from minority groups |

| • Group meeting for poster presentations and seminars |

• 33% of participants pulished articles (20% as first authors) |

||

| • Funded by NIMH | • 47% of participants made conference presentations |

||

| • 99% of participants began to think positively about a career in geriatric mental health research |

|||

| Foster interest in the field of geriatric psychiatry |

Stepping Stones | • One-day workshop at annual research meeting on geriatric psychiatry careers, meetings with geriatric fellowship training directors |

• 476 participants |

| • Supported by American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry |

• 34% of participants responded to the survey: of these, 86% intended to pursue geriatric psychiatry; 70% of those in psychiatry residencies had completed a geriatric fellowship |

||

| Obtain K award or other career development grant |

Summer Research Institute in Geriatric Psychiatry |

• MDs and PhDs without NIH funding participate in one-week intensive research training program including didactics on research career development, individual presentations of developing research by participants, and individual meetings with senior faculty from leading research sites |

• 331 participants trained: 53% MDs, 39% PhDs; 25% minorities, 50% women |

| • Funded by NIMH | • 75% of participants pursued academic careers |

||

| • 90% of participants published ≥1 peer- reviewed article |

|||

| • 68% of participants awarded federally funded grants |

|||

| • 44% of participants obtained career development award funding |

|||

| Increase access to mentoring and career development resources |

MedEd Mentoring Web site | • Web-based seminars and resource materials on geriatric mental health mentoring, early career development, grant opportunities, meetings, and publication |

• 2,149 visits per month (average) since launch in November 2005 |

| • Funded by NIMH SBIR | • 4,733 visits per month in 2008 |

||

| • 5,485 visits in the fourth quarter of 2008 |

|||

| Increase minority early-career investigators |

Institute for Research Minority Training on Mental Health and Aging |

• Three-year postdoctoral program of mentored research at applicant’s institution; centralized group meetings of all fellows for presentation of work in progress |

• 10 participants trained: 1 Asian, 3 Hispanic, and 6 African American participants |

| • Masters degree support | • Nine PhDs and one MD trained | ||

| • Funded by NIA | |||

| Obtain first R01, R34, or R21 grant |

Advanced Research Institute in Geriatric Psychiatry |

• Early career investigators with K awards or VA merit awards are matched with a senior research mentor (outside of their own institution) who has same research interests |

• 42 participants trained (4 cohorts) |

| • Long-distance mentoring for two years | • 71% of participants received R01, R34, or R21 NIH grants, compared with an average of 38% for NIMH K awardees overall |

||

| • Meet with mentor once per year and attend intensive spring research retreat |

|||

| • Funded by NIMH | |||

START-MH indicates Summer Training on Aging Research Topics-Mental Health; NIMH, National Institute of Mental Health; K award, NIH Career Development Award; NIH, National Institutes of Health; SBIR, Small Business Innovative Research; NIA, National Institute on Aging; R01, NIH Major Research Grant; R34, NIH Pilot Intervention and Services Research Grants; R21, NIH Exploratory/Developmental Research Grant.

Implications for the Research Pipeline: Adapting the Successful Programs of GMH Research Career Development to Other Areas

The longitudinal GMH research career development programs (summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1) have significant implications for the development, support, and sustainability of researchers in fields other than GMH. As evidence of this potential application, a variety of similar programs have been directly adapted from the SRI and ARI models outside of the field of GMH research. Specific examples of three- to five-day intensive research development institutes include the Child Intervention, Prevention and Services Summer Research Institute,22 the Career Development Institute for Psychiatry,23 and the Career Development Institute for Bipolar Disorder.24 Another example of an adaptation of the SRI and ARI components is exemplified by the Critical Research Issues in Latino Mental Health conference hosted by the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.25 This three-day conference is specifically targeted at Latino mental health researchers and is intended to connect early-career investigators with senior research mentors from around the nation to improve skills such as grant writing and to provide mentoring opportunities.

As previously described, a longitudinal process can be identified that includes a series of developmental steps warranting programmatic support. These steps include (1) developing opportunities for high school, undergraduate, and master’s degree students to gain exposure to the field at an early age, (2) establishing in-depth learning opportunities that support students in obtaining an early-career-development award, (3) ensuring ongoing support and development of researchers by connecting them with effective mentors and access to a resource clearinghouse (e.g., MedEdMentoring.org), (4) identifying explicit strategies to support the recruitment and participation of minorities and other researchers from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds, and (5) assisting early-career researchers as they transition through each stage of career development from early support to the awarding of their first research grant. The core principles and characteristics incorporated into each of these steps for the design and implementation of career development support are adaptable to other fields and research areas. These core characteristics are described below.

Multidisciplinary, cross-site national programs

GMH research career development programs are cross-site, multicomponent programs that bring together senior researchers, faculty, and students from around the country and across disciplines in an effort to develop future investigators. The collective participation of leaders in research and of faculty members from around the United States serves to increase the impact of each institution as leaders come together to form a critical mass of expertise, training, and support for the benefit of students and the field of GMH research. This approach augments, enhances, and complements local institutional mentoring and training programs.

Small-group and one-to-one consultations and mentoring that emphasize the development of research ideas and proposals

The primary ingredient of the SRI and ARI programs is the opportunity for participants to present their ideas and receive feedback from senior mentors in small-group presentations and one-to-one meetings. In contrast to conventional research meetings that emphasize formal posters or oral presentations of completed research, under this structure, participants are directed to present and seek advice on developing research ideas and proposals. Early-career investigators have the unique opportunity to have protected time to meet with leaders in the field, develop their ideas over the course of the SRI or ARI meeting, and follow up by e-mail and telephone afterward.

Didactics that emphasize the research skills and knowledge that are vital to successful career development and grantsmanship

Didactic presentations are limited to presenting critical information needed to successfully navigate a developing research career, in contrast to conventional research meetings that focus on scientific findings and content areas. Examples of such process-oriented topics include (1) formulation of a clear research question, (2) fundamentals of writing a successful career development award or R01 proposal, (3) manuscript preparation skills, (4) responses to reviews of manuscripts and grants, (5) funding mechanisms, (6) consultation with federal project officers, (7) work with a mentor, (8) project management, (9) consultation with biostatisticians, (10) negotiation of one’s first job offer with a department chair, (11) career advancement and promotion, and (12) the balance of life and work. In addition, mock study sessions and verbal reviews of formative proposals provide a unique opportunity for early-career investigators to gain a firsthand view of the peer-review process.

Shared commitment to research career development as a priority

The university staff, administrators, mentors, and professors share a commitment to developing and supporting early-career investigators as a top institutional priority. Successful mentoring is recognized as an important part of a person’s qualifications for academic promotion, and faculty members are also encouraged to sponsor and support promising early-career investigators. Program funding is dedicated to supporting travel, meeting, and administrative expenses.

Diverse funding strategies

A commitment to seeking and obtaining diverse sources of funding is crucial to the sustainability of the model over time. Funding sources include the government (NIMH, NIA, SBIR, and the National Center for Research Resources), foundations (e.g., The Hartford Foundation), and institutional grants from colleges and universities.

Conclusions

The development, support, and sustaining of researchers are widely recognized as essential components of improving the quality of the nation’s health care by developing the best scientific evidence available and translating that best evidence into clinical practice.26–28 The findings and recommendations of the Summit on Challenges in Recruitment, Retention, and Career Development in Geriatric Mental Health Research present a picture of multicomponent programs for early-career research development that address the endangered flow of future investigators in the field of GMH research. Such longitudinal programmatic initiatives comprise key components and core principles that considerably enhance the field of GMH research. These programs have demonstrated positive outcomes, and yet they are in danger of disappearing in the current, challenging funding environment that prioritizes conventional research grant mechanisms before research training programs. Despite these challenges, the components, principles, and characteristics of these programs hold promise for continued growth in the emerging field of GMH research while also providing a potential blueprint for the development of early-career research in other fields and disciplines.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable contributions of the other participants in the 2007 Summit on Challenges in Recruitment, Retention, and Career Development in Geriatric Mental Health Research: Olusola Ajilore, Colin A. Depp, Jovier Evans, Hochang Benjamin Lee, Jeffrey M. Lyness, Susan McCurry, Jennifer Morse, Christopher F. Murphy, George Neiderehe, Jason T. Olin, Barton W. Palmer, Brian Shanahan, Gwenn Smith, Joel E. Streim, and Warren D. Taylor. We also appreciate the editorial contribution of Monique Miles in preparing this manuscript.

Funding/Support: The authors received honoraria as participants in a workshop organized by MediSpin, Inc. (the developer of MedEdMentoring.org) and supported by Small Business Innovative Research contract no. HHSN278200444084C from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. MediSpin, Inc., also provided logistical support for the workshop. This report is the result of that workshop.

Appendix A

Overview of the Summit on Challenges in Recruitment, Retention, and Career Development in Geriatric Mental Health Research

Overview and Goals of the Summit

Co-Chairs: Barry D. Lebowitz, PhD, and Stephen J. Bartels, MD, MS

Part 1: The Current State of the Research Environment

1.1 The Fragility of the Scientific Infrastructure and the Scope of Emerging Opportunities

Chair: Barry D. Lebowitz, PhD

Part 2: Different Perspectives

2.1 Getting Started: Experiences, Challenges, Concerns, Impressions, and Targeting Opportunities in “Launching Careers” (Early-Career Investigator Session)

Co-Chairs: Olusola Ajilore, MD, PhD, and Colin A. Depp, PhD

Panel: Warachel E. Faison, MD, Jennifer Morse, PhD, and Christopher F. Murphy, PhD

Open Discussion, Summary of Preliminary Recommendations: Jeffrey M. Lyness, MD, Chair

2.2 Keeping Going: Experiences, Challenges, Concerns, Impressions, and Targeting Opportunities in “Advancing Careers” (Junior Faculty Investigator Session)

Co-Chairs: Helen C. Kales, MD, and Susan McCurry, PhD

Panel: Hochang Benjamin Lee, MD, Barton W. Palmer, PhD, and Warren D. Taylor, MD

Open Discussion, Summary of Preliminary Recommendations: Gwenn Smith, PhD, Chair

2.3 Alternate Career Paths: Perspective From Industry

Chair and Open Discussion: Jason T. Olin, PhD

2.4 National Institute of Mental Health Perspective: Challenges and Opportunities

Co-Chairs: George T. Niederehe, PhD, and Jovier Evans, PhD

Part 3: National Training and Mentoring Programs and Resources

3.1 Start-MH, Stepping Stones, SRI, IRMMA, ARI

Chair: Charles F. Reynolds, III, MD

Panel: Martha Bruce, PhD, Warachel E. Faison, MD, Maureen Halpain, MA, and Paul Kirwin, MD

Open Discussion, Summary of Preliminary Recommendations: Charles F. Reynolds, III, MD

4.2 Use of Web-based Technologies: MedEdMentoring, Multi-site Web-based Mentoring

Chair and Open Discussion: Brian Shanahan

Part 4: Solutions and Strategies

4.1 Discussion of Primary Issues, Consensus Recommendations, and Opportunities

Co-Chairs and Open Discussion: Martha Bruce, PhD, and Joel E. Streim, MD

4.3 Priority Issues and Consensus Recommendations

Chair: Stephen J. Bartels, MD

Summary of Recommendations from the Sessions and Next Steps

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Disclaimer: The conclusions in this report represent the consensus judgment of the participants and do not necessarily reflect the policies or programs of MediSpin, Inc., or the National Institute of Mental Health.

Contributor Information

Stephen J. Bartels, Dartmouth Centers for Health and Aging, and professor, Department of Psychiatry and Department of Community and Family Medicine, Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, New Hampshire..

Barry D. Lebowitz, Department of Psychiatry, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, La Jolla, California, and deputy director, Sam and Rose Stein Institute for Research on Aging, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, La Jolla, California..

Charles F. Reynolds, III, Department of Geriatric Psychiatry and Department of Neurology and Neuroscience, and senior associate dean, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania..

Martha L. Bruce, Department of Sociology in Psychiatry, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, White Plains, New York..

Maureen Halpain, Division of Geriatric Psychiatry and Stein Institute for Research on Aging, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, La Jolla, California..

Warachal E. Faison, Alzheimer’s Research and Clinical Programs, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina..

Paul D. Kirwin, Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship Program, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut..

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. Committee on the Future Health Care Workforce for Older Americans. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeste DV, Alexopoulos GS, Bartels SJ, et al. Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health: Research agenda for the next 2 decades. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:848–853. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown University, Duke University, Harvard University et al. A Broken Pipeline? [Accessed June 2, 2009];Flat Funding of the NIH Puts a Generation of Science at Risk: A Follow-up Statement by a Group of Concerned Universities and Research Institutions. Available at: http://www.brokenpipeline.org/brokenpipeline.pdf.

- 4.National Institute of Mental Health. [Accessed October 2, 2009];U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. FY 2007 Funding Strategy for Research Grants. Available at: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-funding/training/overview-of-nimhs-funding-strategy-for-research-training.shtml.

- 5.Bartels SJ. Improving system of care for older adults with mental illness in the United States: Findings and recommendations for the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:486–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed May 22, 2008];NIH Loan Repayment Programs. Available at: http://www.lrp.nih.gov/about/index.htm.

- 7.Training Geriatric Mental Health Services Researchers. NIMH Grant No. T32 MH 073553 (SJ Bartels, Principal Investigator). National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. Awarded July 18, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zerhouni EA. [Accessed October 1, 2009];FY 2009 director’s budget request statement. Available at: http://www.nih.gov/about/director/budgetrequest/fy2009directorssenatebudgetrequest.htm.

- 9.National Center for Research Resources. [Accessed October 1, 2009];Clinical and Translational Science Awards. Available at: http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/clinical_research_resources/clinical_and_translational_science_awards.

- 10.Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs (ADGAP) [Accessed October 1, 2009];The Status of Geriatrics Workforce Study. Fellows in geriatric medicine and geriatric psychiatry programs. Training Pract Update. October 2007;5. Available at: http://129.137.5.214/GWPS/files/ADGAP%20Training%20and%20Practice%20Update%205_2.pdf.

- 11.OpenCongress HR. [Accessed October 1, 2009];Geriatrics Loan Forgiveness Act of 2009. 1457 Available at: http://www.opencongress.org/bill/111-h1457/text.

- 12.Hinrichsen GA. Why multicultural issues matter for practitioners working with older adults. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2006;37:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Racial/Ethnic Diversity in Research Training and Health Disparities Research. An Investment in America’s Future: Racial/Ethnic Diversity in Mental Health Research Careers. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn CR. Picking a research problem: The critical decision. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1530–1533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405263302113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed October 2, 2009];U. S. Medical School Faculty. Available at: http://www.aamc.org/data/facultyroster/reports.htm.

- 16. [Accessed October 1, 2009];National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. MedEd Mentoring. Available at: http://www.mededmentoring.org.

- 17.The START-MH Program. San Diego: University of California; [Accessed October 1, 2009]. Available at: http://startmh.ucsd.edu. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sewell DD. The American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry: My professional family. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31:103–104. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.31.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.University of California at San Diego. [Accessed October 1, 2009];Summer Research Institute. Available at: http://sri.ucsd.edu.

- 20. [Accessed October 1, 2009];Medispin. Community GMH Research. Available at: www.communitygmhresearch.org.

- 21.Weill Medical College of Cornell University. [Accessed October 1, 2009];Advanced Research Institute in Geriatric Mental Health. Available at: http://www.cornellpsychiatry.org/research/ari.html.

- 22.University of Pittsburgh. [Accessed October 1, 2009];Child Intervention, Prevention, and Services Summer Research Institute. Available at: http://www.wpic.pitt.edu/research/chips.

- 23.National Institute of Mental Health. [Accessed October 1, 2009];Career Development Institute for Psychiatry. Available at: http://www.cdipsych.org.

- 24.National Institute of Mental Health. [Accessed October 1, 2009];Career Development Institute for Bipolar Disorder. Available at: http://www.cdibipolar.org.

- 25.Robert Wood Johnson Medical School Department of Psychiatry. [Accessed October 1, 2009];Critical Research Issues in Latino Mental Health. 2009 Available at: http://www2.umdnj.edu/crlmhweb/background.htm.

- 26.Wyngaarden JB. The future of clinical investigation. Cleve Clin Q. 1984;51:567–574. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.51.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko CY, Whang EE, Longmire WP, Jr, et al. Improving the surgeon’s participation in research: Is it a problem of training or priority? J Surg Res. 2000;91:5–8. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones RS, Debas HT. Research: A vital component of optimal patient care in the United States. Ann Surg. 2004;240:573–577. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000140742.22643.0b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]