Abstract

A hallmark of the common Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the pathological conversion of its amphiphatic amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide into neurotoxic aggregates. In AD patients, these aggregates are often found to be tightly associated with neuronal GM1 ganglioside lipids, suggesting an involvement of GM1 not only in aggregate formation but also in neurotoxic events. Significant interactions were found between micelles made of newly synthesized fluorescent GM1 gangliosides labeled in the polar headgroup or the hydrophobic chain and Aβ(1–40) peptide labeled with a BODIPY-FL-C1 fluorophore at positions 12 and 26, respectively. From an analysis of energy transfer between the different fluorescence labels and their location in the molecules, we were able to place the Aβ peptide inside GM1 micelles, close to the hydrophobic-hydrophilic interface. Large unilamellar vesicles composed of a raftlike GM1/bSM/cholesterol lipid composition doped with labeled GM1 at various positions also interact with labeled Aβ peptide tagged to amino acids 2 or 26. A faster energy transfer was observed from the Aβ peptide to bilayers doped with 581/591-BODIPY-C11-GM1 in the nonpolar part of the lipid compared with 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1 residing in the polar headgroup. These data are compatible with a clustering process of GM1 molecules, an effect that not only increases the Aβ peptide affinity, but also causes a pronounced Aβ peptide penetration deeper into the lipid membrane; all these factors are potentially involved in Aβ peptide aggregate formation due to an altered ganglioside metabolism found in AD patients.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most prominent member of the family of devastating neurodegenerative disorders that affect millions of people worldwide (1,2). A hallmark of these diseases is the presence of aberrantly folded protein deposits (1,3). These proteins often have little or no sequence homology, but their conversion from a native state into toxic aggregates is the common feature for these disorders. Therefore, numerous studies have focused on the identification of the protein misfolding processes. However, the molecular mechanisms behind the neurotoxic action of these protein species still remain unknown.

The most studied neurodegenerative disease is AD, which is characterized by amyloidogenic plaques, mainly containing the 39- to 42-residue amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide (4). This amphiphatic peptide is the cleavage product of the >770-residue-long amyloid precursor protein, a single type-1 transmembrane protein whose function is not yet clarified (5,6). Oligomeric aggregates of Aβ peptide are assumed to be the main culprit in AD, as shown by their toxic impact on neuronal cells in cultures and in aged brains (1,3,7). But how can Aβ peptide undergo conversion from a soluble, nontoxic monomer into these aggregates? Even though it is assumed that the conversion into toxic aggregates is an intrinsic property of the peptide (2,8), the actual folding fate is controlled by its immediate surrounding. This environment contains numerous cellular membranes, and these membranes are ideal targets for the amphiphatic Aβ peptide, which contains a hydrophilic (residues 1–28) nonspecific extramembranous part and a hydrophobic helixlike transmembrane part (residue 29–40/42). The membrane anchoring ability (4,5,9) comes from these properties.

It was shown in vitro that the presence of various target membranes could induce accelerated aggregation of Aβ-peptide monomers into amyloidogenic aggregates (10–17), a potential key process in AD pathology (7,18). In general, the presence of charged lipid components induced an electrostatically driven surface accumulation of Aβ-peptide monomers, followed by a much faster conversion into aggregates than would occur in a membrane-free environment (10,15,16).

Many recent studies of AD have focused on the specific role of neuronal membranes, whose interaction with the Aβ peptide might be crucial in the onset and development of the disease (19,20), a research hypothesis that is based on the abundance of amyloid precursor proteins in neurons and the pathologically altered lipid composition observed in many AD patients (21,22). These changes were most dramatic for the lipid family of gangliosides, which are neuronal-membrane-specific sialic-acid-containing glycosphingolipids involved in numerous neurobiological events, including synaptic transmission (23).

Gangliosides have even been found to associate with Aβ peptide in vivo, which make them a prime suspect in pathological Aβ peptide interactions with membranes (14,24). The role of gangliosides in amyloidogenic diseases has been intensely studied by a variety of approaches (11–14,24). A connection between neuronal gangliosides and an accelerated aggregation of Aβ peptide was monitored using a Trp-labeled Aβ(1–40) peptide (25,26). Matzusaki et al. used fluorescence spectroscopy and specifically labeled gangliosides to provide molecular insights into ganglioside-containing raftlike membranes and their role in the pathological behavior of Aβ peptides (13,27–30). It was recently demonstrated that the monosialoganglioside GM1 released from damaged cells can trigger the formation of Aβ fibrils (29). These fibrils are much more toxic than GM1-free fibrils.

Although it is established that gangliosides potentially exhibit a pathological role in the aggregation of Aβ peptides, the molecular nature of the specific ganglioside interactions with Aβ peptide monomers and the subsequent lipid-peptide assemblies during the aggregation process are not yet unraveled. This is also true for the mechanism by which the Aβ peptide interacts with GM-containing membranes, either by surface association or by insertion (27), the latter of which might prevent aggregation inside membranes or enable the formation of potentially toxic transmembrane ion channels (21). However, there is no structural evidence of Aβ peptides inserted into membranes or the impact of such insertion on the surrounding lipids. Only theoretical models exist, and these predict a mutant-dependent partial insertion, which might increase ion-channel formation (34). A recent simulation suggests that the peptide is localized at the interface of the membrane upon proteolytic cleavage (31). In addition, there is even an ongoing discussion concerning the possible role of Aβ-ganglioside micellar structures as in vivo seeds for peptide aggregation (32).

Here, fluorescence methods were used to address the location and behavior of the Aβ peptide in/at ganglioside-containing membrane interfaces on a molecular level, as well as fundamental differences in Aβ peptide behavior upon transfer to a micellar environment (33–35). To obtain information regarding the spatial preference between Aβ(1–40) peptide and gangliosides in micellar and membranous systems, the electronic energy transfer between BODIPY-labeled Aβ(1–40) peptides and BODIPY-labeled GM1 lipids was studied. To study membrane interactions without interference, site-specific mutations within the hydrophilic region (residues 1–28) were used, where a natural amino acid residue was replaced by a Cys residue. This enabled the incorporation of a sulfhydryl-specific fluorescent reporter group. In this study, the BODIPY-FL label was covalently attached to positions 2, 12, and 26, which represent the initial, middle, and ending parts of the postulated hairpin region (36,37). The studied fluorophore-labeled peptides served as donors of electronic energy to either the 564/571-BODIPY or the 581/591-BODIPY acceptor group, localized in the GM1 lipid (cf. Fig. 1). For an effective energy transfer, the peptide-GM1 distances must not exceed ∼60 Å. We observed a strong affinity of Aβ peptides to micelles composed of GM1. In phosphatidylcholine (PC) bilayers containing GM1, the ability of Aβ to bind to the membrane is closely correlated with the clustering of GM1 and its specific location.

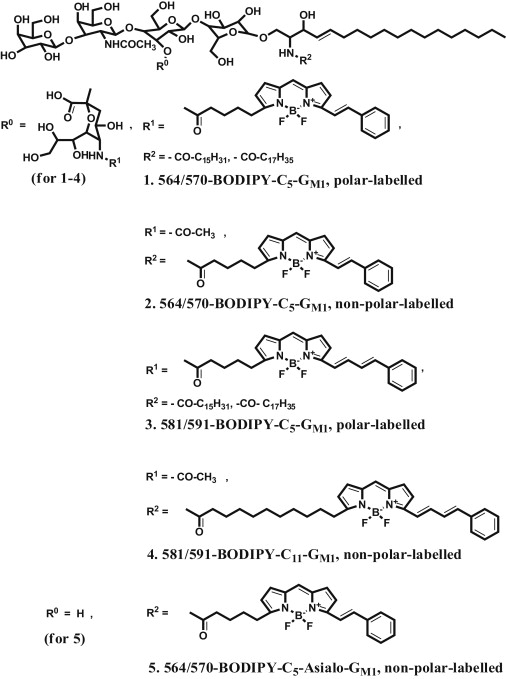

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the BODIPY-labeled gangliosides GM1(1–4) and the BODIPY-labeled Asialo-ganglioside GM1(5).

Materials and Methods

Aβ(1–40) mutants with Cys in positions 2, 12, and 26 were obtained from Alexotech (Umeå, Sweden), with the correct molecular weight verified by MALDI-TOF. To accomplish an efficient dissolution of all peptides before labeling, a procedure described elsewhere (38) was used. The sulfhydryl-specific BODIPY-FL-C1-iodoacetamide (Invitrogen, Gothenburg, Sweden) was linked covalently, as described previously (39). Removal of free probe was achieved by peptide precipitation in 10 volumes of 90% cold acetone. The pellet was dissolved in hexafluoroisopropanol and upon removal was stored as peptide film at −20°C. Before use, the film was treated by the NaOH/dimethylsulfoxide procedure described above. The degree of labeling was determined from absorbance measurements at 280 and 505 nm.

All fluorescent BODIPY-labeled gangliosides were synthesized as described elsewhere (40) The BODIPY-labeled fatty acids and the lipids were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL), respectively. The gangliosides GM1 and GD1a were isolated from bovine brain, as described by Svennerholm (41). The chemical structures of the different BODIPY-labeled gangliosides are displayed in Fig. 1.

Exposure to light was avoided in all handling of the dyes. All solvents used were reagent grade and freshly distilled. A Tris-HCl buffer (20 mM) containing 1 mM EDTA disodium salt, pH 7.4, was used in all experiments with Aβ peptides, micelles, and vesicle systems.

Preparation of micelles

Ganglioside GM1 spontaneously forms micelles in water or buffer at concentrations above the critical micelle concentration (1 μM). In this work, the concentrations used were 3–4 orders of magnitude higher. The concentration of BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβs was ∼1 μM in all experiments, as determined from spectral absorption experiments.

All samples were thermostated at 20°C

Technical details concerning the preparation of vesicles and the spectroscopic experiments are given in the Supporting Material.

Results and Discussion

BODIPY-FL-Aβ(1–40) and micelles of GM1

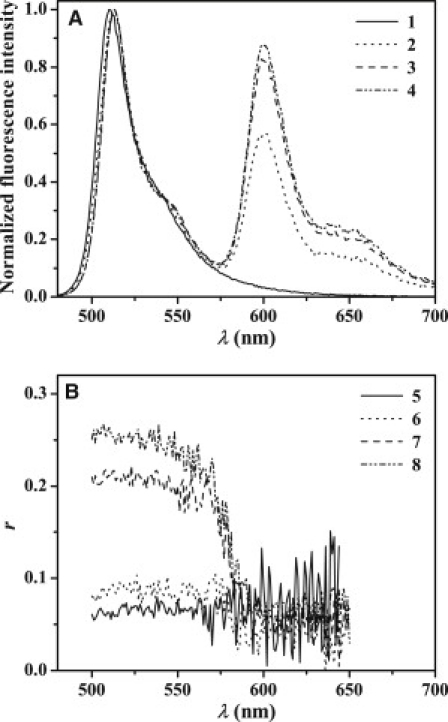

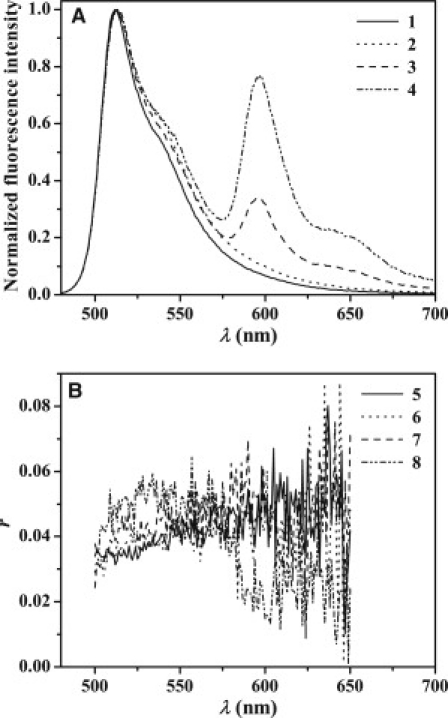

Each of the BODIPY-FL-labeled mutants of the Aβ(1–40) peptide was added to GM1 micelles, which were doped with the 581/591-BODIPY- or 564/570-BODIPY-labeled ganglioside. The location of these fluorescent groups in the ganglioside molecule (Fig. 1) strongly suggests that the fluorescent moieties of the C5-GM1 and C11-GM1 molecules are located in the polar and nonpolar parts of a lipid bilayer, respectively. Upon interaction of BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβ peptides with the micelles, the labeled gangliosides act as acceptors of electronic energy from the donor group BODIPY-FL located in Aβ peptides. Different combinations of donor and acceptor pairs were studied using steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy. The obtained results exhibit very similar patterns. Interactions between the BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβ peptide and micelles are evident from the observed increase of the labeled GM1 fluorescence upon the excitation of BODIPY-FL (Fig. 2). Electronic energy transfer from the BODIPY-FL-labeled peptide (donor) to the 581/591-BODIPY-labeled GM1 (acceptor) explains the relative increase of the fluorescence intensity observed for the latter. Changes of the physicochemical properties in the vicinity of the BODIPY moiety upon addition of micelles to the peptides in water buffer, are indicated by a red shift of the BODIPY-FL absorption spectrum.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence spectra (A) and fluorescence steady-state anisotropy, r (B) of BODIPY-FL-Aβ-Cys12, 0.45 μM in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4 (1 and 5, respectively) and with GM1 micelles containing 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1 (1 mol %), 1:20 mol/mol (2 and 6, respectively), 1:120 mol/mol (3 and 7, respectively), and 1:240 mol/mol (4 and 8, respectively). The excitation wavelength was 470 nm.

To estimate any potential influence of the BODIPY groups attached to lipids, additional experiments were carried out with micelles containing reduced fractions of acceptor-labeled GM1. In these experiments, the Cys26-mutated Aβ peptide labeled with BODIPY-FL was used, whereas the micelles were doped with 564/570-BODIPY-C5-GM1 at a molar ratio of 1 probe-GM1/3000 GM1 molecules. This corresponds to approximately one 564/570-BODIPY-C5-GM1 molecule/18 micelles. Upon addition of micelles to the BODIPY-FL-Aβ peptide, the pattern observed was very similar to that shown in Fig. 2. That is, the fluorescence steady-state anisotropy of the peptide increases rapidly and the fluorescence band of the acceptor 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1 appears.

In addition, to elucidate any influence of the gangliosides on the studied interactions, micelles composed of the GD1a were also prepared. The negatively charged BODIPY-labeled GM1 was replaced with electrically neutral 564/570-BODIPY-C5-Asialo-GM1. The interaction between BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβ peptides and 564/570-BODIPY-C5-Asialo-GM1 in GD1a micelles reveals the same pattern as that obtained for GM1 micelles. Thus, the observed interactions are caused neither by specific interactions with the GM1 lipid nor by specific interactions between the charged labeled lipid (564/570-BODIPY-C5-GM1) and the Aβ peptide.

Fluorescence depolarization in the absence of energy transfer

Time-resolved and steady-state fluorescence depolarization experiments were performed on BODIPY-FL-Cys26-Aβ upon interactions with GM1 micelles that did not contain any acceptor-labeled gangliosides. Here, the acronym BODIPY-FL-Cys26-Aβ stands for the Cys26 mutant of the Aβ(1–40) peptide, which is labeled by a sulfhydryl-specific BODIPY-FL reagent. The studied molar ratios of GM1/BODIPY-FL-Cys26-Aβ were 325:1, 50:1, and 25:1, for which the obtained steady-state anisotropy values were 0.239, 0.162, and 0.124, respectively. Using the recently determined value for the micellar GM1 aggregation number (168 ± 4) (40), the above ratios correspond to average numbers of peptides/micelle of 0.51, 3.4, and 6.7, respectively. In the absence of micelles, the steady-state anisotropy of the peptide is much lower, typically ∼0.06 (vide infra). Therefore, the much higher anisotropy values suggest an efficient association of the peptide molecules to the micelles, a conclusion further supported by the results presented in the following subsections. The lowered anisotropy values obtained with increasing numbers of peptides per micelles can be explained by an increasing rate in electronic energy migration among the BODIPY-FL groups in the micelles. For the most diluted system (1:350), however, it is reasonable to neglect the influence of energy migration. This implies that the steady-state and time-resolved anisotropy are determined by the reorientational motions and local order of the BODIPY-FL group (43). From analyses of these data, an average rotational correlation time of 12.1 ns is obtained. The influence of micellar rotational motion is negligible on the studied fluorescence timescale, since the rotational correlation time of a GM1 micelle is ∼50–60 ns. The negligibility of this influence is also supported by the residual nonzero anisotropy in the decay of the fluorescence anisotropy. Therefore, the obtained average correlation time can be ascribed to local reorienting motions of the BODIPY-FL group in the GM1 micelle. A local order parameter value of 0.66 was calculated from the residual nonzero anisotropy. The high value of the order parameter is compatible with a rather restricted orientation of the BODIPY group.

Fluorescence depolarization and energy transfer

Interactions between Aβ peptides and GM1 micelles are evident from fluorescence depolarization experiments, from which the calculated emission anisotropies (cf. Figs. 2 and 3) were calculated. The anisotropy value of BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ in buffer is rather low, ∼0.06. Using this value and the measured fluorescence lifetime of 4.6 ns, an effective reorientation correlation time of the BODIPY group can be estimated to be ∼1 ns. Assuming that the peptide reorients like a spherical particle, and by using the molecular mass of the BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ (i.e., ∼4500 Da), the calculated rotational correlation time is ∼4 ns. The obtained shorter correlation time is, however, compatible with a flexible peptide structure (9), as well as rapid internal reorientations of the BODIPY group. The steady-state anisotropy of the BODIPY-FL group increases upon adding GM1 micelles, as well as upon increasing the molar ratios between the GM1- and BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβ peptide (cf. Fig. 3). The steady-state anisotropy increases to a maximum value of r ≈ 0.24 for ratios of ∼250:1, which corresponds to an average number of 0.7 Aβ peptides/micelle. The concentration range studied corresponds to an average number of ∼1–8 peptides/micelle. In these experiments, the concentration of the BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ was kept constant (0.45 μM), whereas the micelle concentration was varied. The average fluorescence lifetime of BODIPY-FL increases slightly, with increasing micelle concentration. Upon association between BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβ peptides and micelles, the reorienting rates of the BODIPY-FL group should become slower. Thus, higher anisotropy values are expected and also observed (cf. previous subsection).

Figure 3.

Steady-state fluorescence anisotropy (r) of BODIPY-FL-Aβ-Cys12, 0.45 μM in Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4 with GM1 micelles, containing 1 mol % of 581/591-BODIPY-C5- GM1 (open symbols) and -C11-GM1 (solid symbols) in the range 500–575 nm (circles) and 590–660 nm (triangles). The excitation wavelength was 470 nm.

Micellar bulk phase distributions of BODIPY-labeled GM1 and BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβ peptides

In all experiments, the fraction of BODIPY-labeled GM1 in the micelles was 1 mol % of the total lipid content. Since previous studies have revealed no preferential affinity between BODIPY-labeled and nonlabeled GM1 (34), a Poissonian distribution of the BODIPY-labeled GM1 can be assumed for calculating the probability of finding 0, 1, 2, or more peptides in a micelle. These probabilities are denoted by P0, P1, P2, … . With knowledge of the average number of BODIPY-labeled GM1 molecules/micelle (), the probability of finding an empty micelle is given by . In our particular case, , which corresponds to the probability of . Thus, the probability of finding micelles populated by at least one acceptor (A = BODIPY-labeled GM1) is given by . For electronic energy transfer between a BODIPY-FL group and the acceptor 581/591-BODIPY group connected with GM1, the Förster radius is 60 Å (34). Since the hydrodynamic radius of a GM1 micelle is 54 Å (40), a substantial probability is given for the electronic energy transfer from a BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβ peptide, localized, for instance, at the micellar surface, to a 581/591-BODIPY-labeled GM1. The probability of finding one acceptor/micelle is P1 = 0.313. Taken together, one concludes that the probability of finding at least two acceptors/micelle in the presence of 1 mol % labeled GM1 is 0.5. For electronic energy migration among 581/591-BODIPY groups connected with GM1, the Förster radius is 68 Å (34). Therefore, energy migration among 581/591-BODIPY groups is highly probable within 50% of the micelles. We assume now also a Poissonian peptide distribution among the micelles, and that the bulk-phase concentration is negligible. The studied molar ratio between BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβ peptides and micelles typically ranges from 1 to 8. Under these conditions, the probability of finding at least one peptide (donor (D))/micelle () is limited to . Thus, the joint probability of finding at least one donor and one acceptor localized in a micelle varies between 0.52 and 0.81 for the systems investigated. As is shown in the next section, hardly any dependence on the molar ratio of peptide to micelle is found. This is compatible with a strong affinity for peptide association to GM1 micelles.

Fluorescence lifetime and intensity data

The fluorescence lifetime of BODIPY-FL-Aβ peptides and labeled GM1 lipids was measured by means of the time-correlated single-photon counting technique. For different mixtures of lipid systems and differently labeled peptides, the mean lifetimes of the donor and the acceptors were calculated from the fluorescence decays, which were collected under the magic-angle condition (44). The mean lifetime of the donor increases very weakly with decreasing mole fraction of the BODIPY-FL-Aβ-peptide. For instance, the average lifetime of BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ increases from 4.5 to 5.0 ns upon decreasing the mole fraction from 1:20 to 1:240 in a micelle labeled with 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1. This is compatible with electronic energy transfer, as well as with the presence of excitation traps formed by possible dimerization of BODIPY-FL groups at high local concentrations (45). The fluorescence decay of the acceptor, 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1, is biexponential, with one preexponential factor being negative, as expected in the presence of donor-acceptor energy transfer. Actually, this proves that 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1 molecules are indirectly excited via electronic energy transfer from the donor groups. For pure GM1 micelles (i.e., without any labeled GM1), the mean lifetime decreases for the lowest concentrations of micelles, that is, for the highest number of peptides/micelle. There are two possible explanations for this: either a quenching process due to the formation of ground-state dimers of BODIPY-FL (45) or/and partial donor-donor energy migration (46). For instance, dimer formation cannot be excluded at the BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ/GM1 molar ratio of 1:50, since this corresponds to 5–6 peptides/micelle. On the other hand, the fluorescence (i.e., the photophysics) relaxation of the BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ is not a monoexponential function and the Förster radius of energy migration among BODIPY-FL groups is 58 Å (47). Therefore, partial donor-donor energy migration within a micelle will reduce the observed mean lifetime upon an increase in the number of peptide molecules.

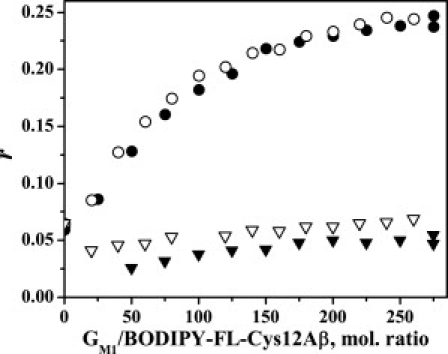

The corrected fluorescence spectra obtained for different molar ratios of BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ and GM1 micelles, doped with the acceptor 581/591-BODIPY are shown in Fig. 2. The efficiency of donor-acceptor energy transfer can be characterized by the intensity ratio , where and denote the peak fluorescence of the donor and acceptor groups. The calculated values of and the probability of finding more than one peptide per micelle () for different donor/acceptor molar ratios are displayed in Fig. 4. For each of the acceptor molecules, 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1 and 581/591-BODIPY-C11-GM1, the dependence on is weak and the two distinct levels obtained are = 0.8 and = 1.1, respectively. A reasonable explanation for the distinct levels reached for probabilities < 0.8 is that most peptide molecules are associated with micelles, i.e., a negligible fraction of peptides are residing in the bulk phase. Note that the and values decrease for probabilities > 0.8, which corresponds to an average number of three or more peptide molecules/micelle. This is compatible with an increased distance between the surfaces of the micelles and the peptides due to the peptide molecule size, whereby the rate of energy transfer would decrease. However, self-quenching of the BODIPY-FL groups at higher concentrations is a more likely explanation (45) and is also supported by the shortened lifetimes observed for BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ in nonlabeled GM1 micelles. In a simplified description, can be modeled according to

| (1) |

where and stand for the time-dependent excitation probabilities of the donor and the acceptor, obtained by solving the master equation of electronic energy transfer probability (48). Furthermore, and ω denote the donor fluorescence lifetime in the absence of energy transfer and the effective rate of energy transfer, respectively. The plateau values of and inserted into Eq. 1 imply that , since . This means that the energy transfer from the BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ peptide is 37.5% faster to a 581/591-BODIPY-C11-GM1 molecule. The effective transfer rate depends on spatially (R) and orientationally distributed donor-acceptor pairs according to

| (2) |

where R0 and stand for the Förster radius and the mean-squared orientation dependence of dipole-dipole coupling, respectively. For the studied donor-acceptor pairs, the value of R0 is the same. For spherical micelles, it is reasonable to assume that , whereby one obtains . For donor-acceptor groups at a fixed distance (i.e., for a distribution), this corresponds to . What are the average locations of the BODIPY-FL group in Cys12-Aβ that would correspond to the observed higher transfer rate to the 581/591-BODIPY group, which is covalently attached to the C11 in the GM1? By inspecting the chemical structure of the GM1 derivatives labeled in the headgroup (C5) and in the acyl chain (C11) together with the known radius of a micelle, one can estimate the distances from the center of a micelle to and , respectively. The obtained average radial distance from the micellar center to the BODIPY-FL group of Cys12-Aβ is 32 Å. This value was calculated using the model described in the Supporting Material.

Figure 4.

The ratio () between the fluorescence intensities of acceptor (FA) and donor (FD) plotted versus the probability of finding at least one donor molecule (BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ) in a GM1 micelle. The acceptors are 581/591-C5-BODIPY-GM1 (black inverted triangles) and 581/591-C11-BODIPY-GM1 (gray triangles) labeled in the hydrophilic and the hydrophobic parts, respectively, of GM1. The acceptor concentration is kept constant at 1 mol % of the total lipid content.

In addition, the transfer rate between the BODIPY-FL-Cys26-Aβ-labeled peptide and the 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1 was studied. The obtained rate () has been compared to that between BODIPY-FL-Cys12-Aβ labeled peptide and the 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1 (). From the ratio of , the distance between the BODIPY-FL group of Cys26-Aβ and the center of a micelle can be calculated by using Eq. S3 in the Supporting Material. Two possible solutions are found, which correspond to distances of 5.6 and 46.7 Å. These distances imply a radial displacement of 26.4 or 14.7 Å between the BODIPY-FL groups attached to mutants Cys12-Aβ and Cys26-Aβ.

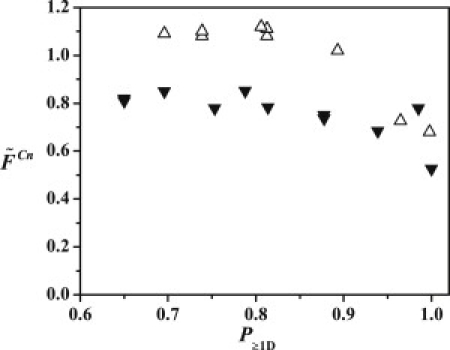

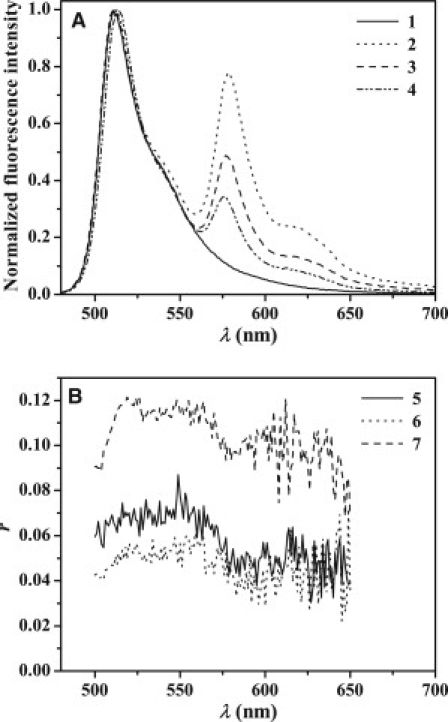

BODIPY-FL-Aβ(1–40) and vesicles containing GM1

We also examined potential interactions between BODIPY-FL-amyloid-β-peptides and large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) of composition GM1/bSM/Chol = 30:40:30 (mol %). In three separate preparations, vesicles were doped with 0.3 mol % of 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1, 581/591-BODIPY-C11-GM1, and 564/571-BODIPY-C5-GM1. In the first and last cases, the BODIPY-FL group is localized in the polar part of the lipid bilayer. This was done with 581/591-BODIPY-C11-GM1, with the fluorophore residing in the nonpolar region. Within a week after the addition of BODIPY-FL-Cys2-Aβ and -Cys26-Aβ to the LUVs, electronic energy transfer was observed from the BODIPY-FL-labeled peptide to each of the labeled GM1 lipids (Fig. 5). In contrast to the studies of GM1 micelles, no significant red shift was observed in the absorption spectra of BODIPY-FL-labeled peptides. It is interesting that a higher efficiency of energy transfer () was observed from BODIPY-FL-Cys2-Aβ to the nonpolar labeled 581/591-BODIPY-C11-GM1 than to the polar-labeled 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1. The decrease in BODIPY-FL emission and the increase in 581/591-BODIPY emission were stronger for the acceptor localized in the nonpolar region (cf. Fig. 5). This observation indicates a penetration of the Aβ peptide into the lipid bilayer of the studied LUV. A penetration is also revealed by the transfer efficiencies obtained for BODIPY-FL-Cys26-Aβ. Furthermore, these observations indicate shorter average distances from the labels in the 2nd and 26th positions of the peptide to the acceptor localized in the nonpolar part of the ganglioside compared to the acceptors localized in the polar region. Therefore, the efficiency of energy transfer (i.e., the values) for the studied positions were analyzed by a model similar to that used for the GM1 vesicles. However, the values obtained were unphysical for distances between the center of the lipid bilayer and the labeling positions. This can be expected if the mutual lateral distribution of the peptides and/or the lipid components is nonrandom. Since the transfer efficiency was greater for BODIPY-FL-Cys2-Aβ than for BODIPY-FL-Cys26-Aβ, the former residue appears to be located closer to the acceptor connected with the hydrophobic ganglioside region.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence spectra (A) and steady-state fluorescence anisotropy, r (B) of BODIPY-FL-Cys2-Aβ, 5 μM in Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4 (1 and 5, respectively) and of LUV:s composed of GM1/bSM/Chol at molar ratio 3:4:3 (250 μM GM1) unlabeled (2 and 6, respectively), and doped with 0.3 mol % 581/591-BODIPY-C5-GM1 (3 and 7, respectively) and 581/591-BODIPY-C11-GM1 (4 and 8, respectively). The excitation wavelength was 470 nm.

As seen here, the presence of gangliosides in the lipid membranes has major consequences for the behavior of the Aβ peptide. Normally, the peptide does not penetrate into bilayers composed of simple mixed phospholipids, such as phosphatidylcholine/phosphatidylglycerol, but prefers the surface region, as various biophysical studies suggest (9,16). However, the presence of charged gangliosides, with their specific headgroup regions, enables the peptide to pass the membrane surface barrier and partially penetrate into the membrane interior. This behavior is not unusual, as has been indicated by earlier work on ganglioside-containing lipid systems (9–16), as well as from molecular dynamics simulations (49). Therefore, it is clear that upon release of the Aβ peptide in vivo into a membrane-free aqueous environment, it still can reinsert itself into membranes if in contact with target membranes containing ganglioside. As indicated by our experiments, there seems to be a two-step mechanism. In the first step, the peptide can bind to the membrane surface, a process severely enhanced by a clustering of the gangliosides in phosphatidylcholine lipid membranes, as discussed further below. In the second step, the surface-adsorbed peptide molecules can penetrate partially into the neuronal membrane system, as indicated by our fluorescence data.

In LUVs, the steady-state anisotropy of the BODIPY-FL group in Aβ is relatively low compared to the values found for GM1 micelles. Even in the absence of labeled GM1, one obtained low and very similar anisotropy values. Addition of the detergent Triton X-100 converted vesicles into mixed micelles (50). As a consequence, the peptide molecules were distributed over many micelles, a process that should decrease the influence of energy transfer, whereas the fluorescence anisotropy of the BODIPY-FL group in Aβ should increase. However, it turns out that the anisotropy was not reaching the same high level as in the experiments carried out with GM1 micelles, as illustrated in Fig. 6. Taken together, these results clearly suggest different spatial distributions of the peptides in a water-lipid interface of GM1 micelles, as compared to mixed micelles formed by Triton X-100 solubilization of lipid vesicles.

Figure 6.

(A) Fluorescence spectra of BODIPY-FL-Cys26-Aβ, 4 μM in Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4 (1), directly after addition of LUVs composed of GM1/bSM/Chol in the molar ratio 3:4:3 (470 μM GM1) and containing 0.6 mol % 564/571-BODIPY-C5-GM1 (2), after 6 days incubation (3), and after addition of Triton X-100 (4). (B) Steady-state fluorescence anisotropy, r, of systems 2–4 in A. The excitation wavelength was 470 nm.

A comparison between Aβ interactions with micelles and lipid bilayers

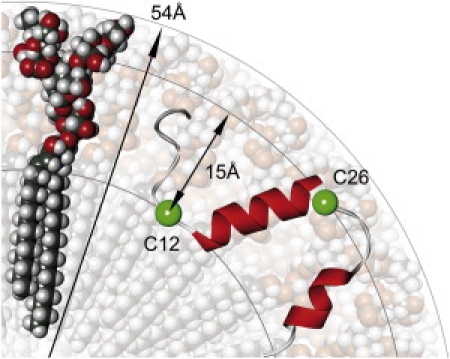

It has been suggested that charged lipids are needed to bind the Aβ peptide to the lipid surface (10,16). In this work, energy-transfer experiments clearly reveal strong interactions between Aβ peptides and GM1 micelles, in agreement with previous studies (51). Yanagisawa et al. (51) assumed that the peptides form aggregates in solution, and that these aggregates are destroyed by the presence of GM1 micelles. It is likely that the peptides can incorporate into the micelles themselves, a process that would be consistent with the observed changes in energy transfer and steady-state anisotropy of the BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβ peptide. Upon incorporation of the peptides, the rate of energy transfer reaches a maximum, whereas the rate decreases upon further addition of micelles, because the number of peptides per micelle decreases. This is very similar to the results obtained for the same peptide with GM1 micelles in the absence of labeled GM1 lipids. From our analysis of the obtained energy-transfer data, it is possible to position the BODIPY-FL groups of the Aβ-peptide in GM1 micelles. The most probable localization (Fig. 7) has been derived from distances calculated between the center of a micelle and the BODIPY-FL groups, as well as from structural data obtained from NMR experiments with the Aβ peptide in micellar systems (52–55). In contrast to the behavior of the Aβ peptide in micelles of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), with its small hydrophilic interface (52,55), the peptide in GM1 micelles is located much deeper. This can be ascribed to the thick hydrophilic region (∼27 Å) of GM1 micelles, which is created by the voluminous carbohydrate lipid headgroups. In this region, there is enough space to locate the hydrophilic N-terminus, whereas in SDS micelles this part already extends into the aqueous environment (52). The first helix is still part of the extramembranous segment (1–28) of Aβ peptide and is therefore, not surprisingly, oriented toward the more polar part of the headgroup region, in agreement with our measurements. Additional support for this positioning of the peptide was recently obtained from NMR studies using lyso-GM1 micelles (53,54). The results strongly suggest peptide-induced changes of the NMR signals from the carbohydrate region, which indicate perturbations exactly in the area where our peptide is located. Supplementary NMR experiments using labeled peptide in these micelles provided a more molecular view of these perturbations (54). Moreover, the type of up-and-down topology they observed is reflected in our model, where the hydrophobic, helical part of the peptide is pointing toward the more hydrophobic center of the micelle. Recent MD simulations on the structure of the Aβ(1–40) peptide in model membranes reflect a similar location and topology at the interface (31). Nevertheless, because of the smaller interface region in these membranes and in SDS micelles, the hydrophobic parts of the peptides are positioned deeper in the hydrophobic membrane region, as compared to GM1 micelles, with their much larger carbohydrate region and less steep gradient from hydrophobic to hydrophilic environment.

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of the Aβ peptide position in GM1 micelles. A space-filling model of the ganglioside GM1 is indicated in the segmental volume of a spherical micelle. The hydrodynamic radius of the micelle is 54 Å, and the radial distance between the BODIPY-FL groups, indicated by the green spheres labeled C12 and C26, is 15 Å.

The interactions between the Aβ peptide and bilayers of LUVs appear more complex compared to ganglioside micelles. Despite the presence of negatively charged phosphatidylglycerol in bilayers (composed of DOPC/DOPG at a molar ratio of 2:1), no energy transfer was observed. For this composition, however, Matsuzaki et al. (28) have reported interactions with Aβ peptides. On the other hand, no interaction was reported for the composition of DOPC/GM1 = 10:1 (molar ratio) (13). The same report also claimed that the Aβ peptide interacts with GM1/bSM/Chol = 20:64:16 (mol %). In the study presented here, no interactions were observed for the latter mixture. However, upon addition of GM1 to lipid bilayers composed of GM1/bSM/Chol = 30:40:30 (mol %), energy transfer was observed from Aβ peptides to the labeled GM1, accompanied by a small increase in the steady-state anisotropy of the Aβ peptide. This is compatible with an increased reorientational restriction of the peptide.

For a comparison among the different observed interactions between Aβ peptide and micelles or LUVs, the average surface density of the peptide in the membrane was estimated. By using the hydrodynamic GM1 micellar radius of 5.4 nm (40), one obtains an average surface area of 42,250 Å2/micelle. The average aggregation number, i.e., the number of GM1 molecules that form a micelle, is 167 (40). Considering the studies of interactions between Aβ peptide and GM1 micelles for peptide/ganglioside molar ratios ranging between 1:20 and 1:240, the average surface density lies within the range of one peptide per 4970–60,360 Å2. For the LUV system studied, the corresponding surface density is 9380 Å2/peptide. Note that these numbers are based on the assumption of a random distribution of peptides on the surface. However, the steady-state emission anisotropy of the BODIPY-FL-labeled Aβ peptide is much lower in interactions with LUVs (0.044) than in those with GM1 micelles (0.127). The anisotropy value obtained for the LUV system is very similar to that obtained for the peptide in bulk solution, i.e., in the absence of vesicles. Such an efficient depolarization is not expected if the peptides are associated with the lipid surface as they are for micelles. This reduction in anisotropy can be ascribed to a more efficient energy migration, which is possible if gangliosides tend to cluster in the bilayer. Therefore, the mean distance between the BODIPY-FL groups becomes shorter, whereby a more rapid energy migration occurs and a lower anisotropy should be obtained.

As our results show, gangliosides as important neuronal membrane compounds exert interactions with Aβ peptides quite differently from common membrane-forming lipids, e.g., phosphatidylserines. The nature of this specific ganglioside-Aβ-peptide interplay might therefore be crucial in AD accompanying aggregate formation in humans, caused by alterations in ganglioside metabolism that are age- and/or disease-related.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Malgorzata Wilzynska for valuable help in labeling of the peptides and to Dr. Natalia Gretskaya for valuable help in the synthesis of ganglioside probes. We are also grateful to Oleg Opanasuyk, MS, for drawing Fig. 7 and to Erik Rosenbaum, MS, for the linguistic review.

This work was financially supported by the Swedish Research Council and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (L.B.-Å.J.).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Selkoe D.J. Cell biology of protein misfolding: the examples of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:1054–1061. doi: 10.1038/ncb1104-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glabe C.G. Common mechanisms of amyloid oligomer pathogenesis in degenerative disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2006;27:570–575. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh D.M., Tseng B.P., Selkoe D.J. The oligomerization of amyloid β-protein begins intracellularly in cells derived from human brain. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10831–10839. doi: 10.1021/bi001048s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masters C.L., Simms G., Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haass C., Selkoe D.J. Cellular processing of β-amyloid precursor protein and the genesis of amyloid β-peptide. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 1993;75:1039–1042. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90312-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheuermann S., Hambsch B., Multhaup G. Homodimerization of amyloid precursor protein and its implication in the amyloidogenic pathway of Alzheimer's disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:33923–33929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haass C., Selkoe D.J. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid β-peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucciantini M., Giannoni E., Stefani M. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature. 2002;416:507–511. doi: 10.1038/416507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bokvist M., Lindström F., Gröbner G. Two types of Alzheimer's β-amyloid (1–40) peptide membrane interactions: aggregation preventing transmembrane anchoring versus accelerated surface fibril formation. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:1039–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aisenbrey C., Bechinger B., Gröbner G. Macromolecular crowding at membrane interfaces: adsorption and alignment of membrane peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;375:376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chi E.Y., Frey S.L., Lee K.Y. Ganglioside G(M1)-mediated amyloid-β fibrillogenesis and membrane disruption. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1913–1924. doi: 10.1021/bi062177x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kakio A., Nishimoto S.-I., Matsuzaki K. Interactions of amyloid β-protein with various gangliosides in raft-like membranes: importance of GM1 ganglioside-bound form as an endogenous seed for Alzheimer amyloid. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7385–7390. doi: 10.1021/bi0255874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuzaki K. Physicochemical interactions of amyloid β-peptide with lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1935–1942. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaurin J., Chakrabartty A. Membrane disruption by Alzheimer β-amyloid peptides mediated through specific binding to either phospholipids or gangliosides. Implications for neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:26482–26489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy R.M. Kinetics of amyloid formation and membrane interaction with amyloidogenic proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1923–1934. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terzi E., Hölzemann G., Seelig J. Interaction of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptide(1–40) with lipid membranes. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14845–14852. doi: 10.1021/bi971843e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeow E.K.L., Clayton A.H.A. Enumeration of oligomerization states of membrane proteins in living cells by homo-FRET spectroscopy and microscopy: theory and application. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3098–3104. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.099424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartmann T., Kuchenbecker J., Grimm M.O.W. Alzheimer's disease: the lipid connection. J. Neurochem. 2007;103(Suppl 1):159–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simons M., Keller P., Simons K. Cholesterol depletion inhibits the generation of beta-amyloid in hippocampal neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:6460–6464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawamura N., Morishima-Kawashima M., Ihara Y. Mutant presenilin 2 transgenic mice. A large increase in the levels of Aβ 42 is presumably associated with the low density membrane domain that contains decreased levels of glycerophospholipids and sphingomyelin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:27901–27908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kracun I., Kalanj S., Cosovic C. Cortical distribution of gangliosides in Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem. Int. 1992;20:433–438. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(92)90058-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kracun I., Kalanj S., Talan-Hranilovic J. Brain gangliosides in Alzheimer's disease. J. Hirnforsch. 1990;31:789–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagai Y. Functional roles of gangliosides in bio-signaling. Behav. Brain Res. 1995;66:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yanagisawa K. Role of gangliosides in Alzheimer's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:1943–1951. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choo-Smith L.P., Garzon-Rodriguez W., Surewicz W.K. Acceleration of amyloid fibril formation by specific binding of Aβ-(1–40) peptide to ganglioside-containing membrane vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:22987–22990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.22987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choo-Smith L.P., Surewicz W.K. The interaction between Alzheimer amyloid β(1–40) peptide and ganglioside GM1-containing membranes. FEBS Lett. 1997;402:95–98. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kakio A., Nishimoto S.I., Matsuzaki K. Cholesterol-dependent formation of GM1 ganglioside-bound amyloid β-protein, an endogenous seed for Alzheimer amyloid. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:24985–24990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuzaki K., Horikiri C. Interactions of amyloid β-peptide (1–40) with ganglioside-containing membranes. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4137–4142. doi: 10.1021/bi982345o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada T., Wakabayashi M., Matsuzaki K. Formation of toxic fibrils of Alzheimer's amyloid β-protein-(1–40) by monosialoganglioside GM1, a neuronal membrane component. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;371:481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakabayashi M., Matsuzaki K. Formation of amyloids by Aβ-(1–42) on NGF-differentiated PC12 cells: roles of gangliosides and cholesterol. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;371:924–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyashita N., Straub J.E., Thirumalai D. Structures of β-amyloid peptide 1–40, 1–42, and 1–55—the 672–726 fragment of APP—in a membrane environment with implications for interactions with γ-secretase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17843–17852. doi: 10.1021/ja905457d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto N., Hasegawa K., Yanagisawa K. Environment- and mutation-dependent aggregation behavior of Alzheimer amyloid β-protein. J. Neurochem. 2004;90:62–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mikaelsson T., Sachl R., Johansson L.B.-Å. Electronic energy transport and fluorescence spectroscopy for structural insights into proteins, regular protein aggregates and lipid systems. In: Geddes C.D., editor. Reviews in Fluorescence 2007. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 53–86. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marushchak D., Gretskaya N., Johansson L.B. Self-aggregation—an intrinsic property of G(M1) in lipid bilayers. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2007;24:102–112. doi: 10.1080/09687860600995235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bogen S.-T., de Korte-Kool G., Johansson L.B.-Å. Aggregation of an α-helical transmembrane peptide in lipid phases, studied by time resolved fluorescence spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:8344–8352. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Durell S.R., Guy H.R., Pollard H.B. Theoretical models of the ion channel structure of amyloid β-protein. Biophys. J. 1994;67:2137–2145. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80717-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Y., Shen J., Jiang H. Conformational transition of amyloid β-peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:5403–5407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501218102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stine W.B., Jr., Dahlgren K.N., LaDu M.J. In vitro characterization of conditions for amyloid-β peptide oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11612–11622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fa M., Bergström F., Ny T. The structure of a serpin-protease complex revealed by intramolecular distance measurements using donor-donor energy migration and mapping of interaction sites. Structure. 2000;8:397–405. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sachl R., Mikhalyov I., Johansson L.B. A comparative study on ganglioside micelles using electronic energy transfer, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and light scattering techniques. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:4335–4343. doi: 10.1039/b821658d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svennerholm L. In: Methods in Carbohydrate Chemistry. Gangliosides, isolation. Whistler R.L., BeMiller J.N., editors. vol. 6. Academic Press; New York: 1972. pp. 464–474. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reference deleted in proof.

- 43.Heyn M.P. Determination of lipid order parameters and rotational correlation times from fluorescence depolarization experiments. FEBS Lett. 1979;108:359–364. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lakowicz J.R. 3rd ed. Springer; Singapore: 2006. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergström F., Mikhalyov I., Johansson L.B. Dimers of dipyrrometheneboron difluoride (BODIPY) with light spectroscopic applications in chemistry and biology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:196–204. doi: 10.1021/ja010983f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalinin S., Johansson L.B.-Å. Utility and considerations of donor-donor energy migration as a fluorescence method for exploring protein structure-function. J. Fluoresc. 2004;14:681–691. doi: 10.1023/b:jofl.0000047218.51768.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karolin J., Johansson L.B.-Å., Ny T. Fluorescence and absorption spectroscopic properties of dipyrrometheneboron difluoride (BODIPY) derivatives in liquids, lipid membranes, and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:7801–7806. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalinin S.V., Molotkovsky J.G., Johansson L.B.-Å. Partial donor-donor energy migration (PDDEM) as a fluorescence spectroscopic tool for measuring distances in biomacromolecules. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2002;58:1087–1097. doi: 10.1016/s1386-1425(01)00613-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mobley D.L., Cox D.L., Longo M.L. Modeling amyloid β-peptide insertion into lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2004;86:3585–3597. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.032342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shnyrova A.V., Ayllon J., Frolov V.A. Vesicle formation by self-assembly of membrane-bound matrix proteins into a fluidlike budding domain. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:627–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanagisawa K., Odaka A., Ihara Y. GM1 ganglioside-bound amyloid β-protein (A β): a possible form of preamyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Med. 1995;1:1062–1066. doi: 10.1038/nm1095-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jarvet J., Danielsson J., Gräslund A. Postioning of the Alzheimer Aβ(1–40) peptide in micelles using NMR and paramagnetic probes. J. Biomol. NMR. 2007;39:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Utsumi M., Yamaguchi Y., Kato K. Up-and-down topological mode of amyloid β-peptide lying on hydrophilic/hydrophobic interface of ganglioside clusters. Glycoconj. J. 2009;26:999–1006. doi: 10.1007/s10719-008-9216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yagi-Utsumi M., Kameda T., Kato K. NMR characterization of the interactions between lyso-GM1 aqueous micelles and amyloid β. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:831–836. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coles M., Bicknell W., Craik D.J. Solution structure of amyloid β-peptide(1–40) in a water-micelle environment. Is the membrane-spanning domain where we think it is? Biochemistry. 1998;37:11064–11077. doi: 10.1021/bi972979f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.