Abstract

Orientation, dynamics, and packing of transmembrane helical peptides are important determinants of membrane protein structure, dynamics, and function. Because it is difficult to investigate these aspects by studying real membrane proteins, model transmembrane helical peptides are widely used. NMR experiments provide information on both orientation and dynamics of peptides, but they require that motional models be interpreted. Different motional models yield different interpretations of quadrupolar splittings (QS) in terms of helix orientation and dynamics. Here, we use coarse-grained (CG) molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to investigate the behavior of a well-known model transmembrane peptide, WALP23, under different hydrophobic matching/mismatching conditions. We compare experimental 2H-NMR QS (directly measured in experiments), as well as helix tilt angle and azimuthal rotation (not directly measured), with CG MD simulation results. For QS, the agreement is significantly better than previously obtained with atomistic simulations, indicating that equilibrium sampling is more important than atomistic details for reproducing experimental QS. Calculations of helix orientation confirm that the interpretation of QS depends on the motional model used. Our simulations suggest that WALP23 can form dimers, which are more stable in an antiparallel arrangement. The origin of the preference for the antiparallel orientation lies not only in electrostatic interactions but also in better surface complementarity. In most cases, a mixture of monomers and antiparallel dimers provides better agreement with NMR data compared to the monomer and the parallel dimer. CG MD simulations allow predictions of helix orientation and dynamics and interpretation of QS data without requiring any assumption about the motional model.

Introduction

Integral membrane proteins perform a variety of vital cellular functions. Features such as orientation, oligomerization, protein dynamics, and specific and aspecific interactions between lipids and transmembrane helices are encoded in the amino acid sequence of membrane proteins and the lipid composition, but it is a challenge to understand the main determinants of membrane protein structure based on complex natural sequences and heterogeneous membranes (1–3). Biophysical characterization of model membrane proteins is a powerful approach to dissecting all contributing factors (4–6). Synthetic peptides in particular have been widely used to investigate aspects of membrane protein structure and dynamics (7–11).

The concept of hydrophobic matching between the hydrophobic part of the protein and the hydrophobic core of the bilayer was introduced with the so-called mattress model (12). Many experimental studies have shown that it plays an important role in regulating the structure of biological membranes and the function of transmembrane proteins (1,13,14). To study this effect in detail, Killian and co-workers developed systematic series of model peptides consisting of a poly-(leucine-alanine) stretch of variable length flanked by two tryptophans (WALP), lysines (KALP), or other residues at the N-terminus and C-terminus (15). Both WALP and KALP peptides adopt a transmembrane α-helical conformation in lipid bilayers (16). Under positive hydrophobic mismatch (i.e., when the hydrophobic length of the peptide is larger than the hydrophobic thickness of the lipid bilayer), these peptides undergo a reorientation that depends on the nature of the lipid bilayer and the flanking residues (16–19).

The orientation of a transmembrane helix within a bilayer is generally defined in terms of the helix tilt angle, τ, between the helix axis and the bilayer normal and the azimuthal rotation, ρ, which describes the direction in which the peptide tilts with respect to a reference residue, e.g., Gly1 (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). These angles can be estimated from experimentally measured quadrupolar splittings (QS) obtained from 2H solid-state NMR experiments using the so-called geometric analysis of labeled alanine (GALA) method (18,19). Recent studies showed a systematic increase of the tilt angle upon membrane thinning (i.e., increasing positive hydrophobic mismatch), but gave surprisingly small values for the tilt angle (e.g., ∼5° for WALP23 in dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC) (17,18)). Moreover, the direction of the peptide tilt (the azimuthal rotation) depended on the nature of the flanking residues around the hydrophobic stretch of the peptide (i.e., Trp or Lys) (17).

Numerous atomistic simulation studies of WALP and KALP peptides in lipid bilayers have been reported (20–24). In all cases, the tilt angle predicted by the simulations was significantly larger (e.g., ∼30° for WALP23 in DMPC (24)) than that determined from 2H NMR (17–19). Fuchs and co-workers, as well as Salgado and co-workers, hypothesized that the small tilt angles obtained experimentally with the GALA method could be the result of averaging effects in the interpretation of the NMR data, and that higher instantaneous values of the tilt angle are more likely (20,24). The basic problem is that extracting the orientation of a peptide from QS requires knowledge of the peptide motion within the timescale of the experiment (which typically is on the order of the inverse of the frequency of the interaction, e.g., 1/10 kHz ∼ 100 μs for 2H QS). Recently, an approach was proposed that takes this motion into account by assuming Gaussian distributions around a mean tilt and rotation instead of a single value for both angles (25). This led to significantly larger values of tilt (e.g., ∼14–18° for WALP23 in DMPC) compared to those from the static GALA method. Alternatively, simulations can help interpret experimental data by directly simulating the motions that occur within the timescale of the experiment. However, this requires extension of the simulation timescale to observe the slowest motions, i.e., rotational motion about the helix axis, which occurs on the hundreds-of-microseconds regime.

In this work, we calculate the orientation of the WALP23 peptide in different phosphatidylcholine (PC) lipid bilayers using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with the coarse-grained (CG) MARTINI force field (26,27). The advantage of these CG simulations is that a timescale of tens of microseconds can easily be reached, approaching the timescale of motional averaging in NMR experiments. This timescale is also sufficient to obtain a near-equilibrium sampling of rotational motions of transmembrane helices, at a level of detail that still includes side chains. We compare 2H QS data calculated from CG simulations with previous atomistic simulations and with NMR data. The significantly better sampling obtained with the CG approach results in an improved agreement of calculated QS with experimental results. The simulations give distributions of helical orientations without the need for any assumption about motional models. These distributions can be used for the interpretation of NMR data. We also investigate the effect of peptide dimerization on QS and the peptide orientation. An equilibrium between monomeric and dimeric forms of WALP23 yields QS values compatible with experimental results.

Methods

System setup

We simulated the WALP23 peptide in three different lipid bilayers of 72 lipids, namely dilaureylphosphatidylcholine (DLPC), dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC), and dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DOPC). For each bilayer, we carried out simulations of a single peptide (peptide/lipid (P/L) ratio of 1:72) and of a preassembled dimer (P/L ratio of 1:36) using both parallel (P) and antiparallel (AP) orientations of the peptides. We thus performed three simulations of the monomer, three of the P dimer, and three of the AP dimer. The peptides were embedded in the bilayers using the approach described by Kandt et al. (28). The dimers were constructed on the basis of previous modeling in vacuum (29). In all simulations, the termini (Gly1 and Ala23) were not charged, to mimic the capped neutral termini in the experiments (18). One additional set of simulations of dimers was performed in DLPC and DOPC starting from two separated peptides. Four simulations were run for P and AP dimers.

Force field and simulation details

The simulations were carried out using the MARTINI coarse-grained force field (26,27). In this force field, each particle represents four nonhydrogen atoms, with the exception of ring-containing molecules, which are mapped with higher resolution (up to two nonhydrogen atoms per particle). Both electrostatic and Lennard-Jones interactions were calculated using a 1.2-nm cutoff with switch function; the distances to start switching Coulomb and Lennard-Jones interactions were 0 and 0.9 nm, respectively. The neighbor list was updated every 10 steps and the relative dielectric constant for the medium was set to 15. This is the standard procedure for the MARTINI force field (26). Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all dimensions. The temperature for each group (peptide, lipid, water) was kept at 300 K using the Berendsen temperature coupling algorithm (30) with a time constant of 1 ps. Note that all three bilayers are fluid at 300 K with the MARTINI force field, including DPPC, which has a gel-to-fluid phase transition temperature of 295 K in this model and cannot be distinguished from DMPC (31). The pressure was kept constant using the Berendsen algorithm. Pressure coupling was semiisotropic, with a pressure of 1 bar independently in the plane of the membrane and perpendicular to the membrane, and a time constant of 4 ps. The integration time step was 40 fs, and structures were saved every 100 ps for analysis. Note that due to lower friction, the dynamics in simulations using the CG model is faster compared to atomistic simulations.

All CG simulations were carried out for 1 μs for WALP23 monomers and either 5 (preassembled dimers) or 10 μs (starting from separated peptides) for the dimers, using GROMACS 3.3.1 (32,33).

Trajectory analysis

The peptide orientation was defined in terms of tilt angle, τ, and azimuthal rotation, ρ (see Fig. S1, consistent with work by others (17–19,24).). The tilt angle was calculated from the first eigenvector of the inertia matrix of all backbone beads. The azimuthal rotation corresponds to the angle between the direction of the tilt and a vector orthogonal to the helix axis that passes through the Cα of Gly1. The anticlockwise direction is taken as positive.

In simulations performed with an atomistic model, it is possible to calculate directly the 2H-NMR QS (Δνiq (kHz)) as if the side chain of each alanine i were labeled with 2H:

| (1) |

where θi is defined as the angle between the magnetic field (taken as the z axis) and the Cα−Cβ bond of alanine i. The angled brackets indicate an average over all the conformations generated in the MD trajectory, whereas in the NMR experiment this corresponds to an ensemble and time average. K is the product of the quadrupolar coupling constant (e2qQ/h), which has the dimension of a frequency (Q is the nuclear quadrupole moment, q is the principal component of the electric field gradient tensor (i.e., qzz), e is the electronic charge, and h is Planck's constant) times an order parameter (S). For K, we used the same value of 49 kHz as in the experiment with which we compare our simulations (18). This value was obtained from an experiment on a dry powder sample of WALP23-Ala-d4 peptide and corresponds to S = 0.875.

In the CG force field, alanine is represented by a single particle including both the backbone and the side chain, with no explicit Cα−Cβ bond. To calculate QS from CG simulations, we used the equation of the GALA method, which relates QS to the orientation of the peptide:

| (2) |

where τ is the tilt angle, ɛi‖ is the angle between the helix axis and the Cα-Cβ bond vector of alanine i and δi describes the azimuth of alanine i (δi is directly related to the azimuthal rotation, ρ, defined above (see Supporting Material, especially Fig. S1, for details on ɛi‖ and δi). In summary, calculations of QS from CG-MD rely on two angles obtained directly from the simulations (τ and ρ) and the assumption of an ideal α-helical geometry. Notice that simulations provide instantaneous values of QS; therefore, time averaging is performed on QS as in Eq. 2, not on the angle θ.

The hydrophobic length of the peptide was calculated as the distance between the center of mass of residues Leu4 and Leu20, whereas the hydrophobic thickness of the lipid bilayers was evaluated as the average distance between the centers of mass of the first hydrophobic bead in the lipid tails in the two leaflets. The dimer population was evaluated based on the minimum distance between any atoms of the two peptides. A threshold distance of 0.5 nm was used.

Molecular docking

Rigid body docking of all-atom WALP23/WALP23 dimer was performed using FTDock (34) with standard parameters. The calculations were done in vacuum and electrostatic interactions were excluded so that only surface complementarity was considered. To improve statistics, we ran 40 calculations with initial structures taken from a clustering of previous all-atom dimer simulations (27) (20 P and 20 AP). Different rotamers were used as initial structures for the docking calculations.

Other details on the docking procedure, the analysis of orientation distributions, and the GALA analysis are described in the Supporting Material.

Results

CG MD simulations reproduce experimental QS better than atomistic simulations

Table 1 shows a comparison between the QS values calculated from CG MD, the experimental values (measured in an unoriented sample (18); see also the right panels of Fig. S2), and previous results from all-atom simulations on DMPC (24). CG simulations of monomeric peptides yield on average a deviation of ∼2 kHz from experimental QS, significantly less than that obtained from atomistic simulations. To verify the reproducibility of our CG simulations, 10 independent runs of the WALP23 monomer in DLPC were carried out. Results were very reproducible, with a standard deviation of 1 kHz for the calculated QS. In contrast, individual atomistic simulations of a few tens to hundreds of nanoseconds gave deviations of 10–20 kHz (24). Only the concatenation of the atomistic trajectories, corresponding to 1.1 μs of sampling, yielded a relatively small deviation (3.1 kHz), comparable to CG MD results. This illustrates the importance of sampling in the accurate prediction of QS from molecular simulations.

Table 1.

Average deviation from experimental QS for monomer and dimer CG and some all-atom simulations

| System | Simulation method | Force field/Method | Lipid | Simulation time (ns) | % Dimer | δΔνq (kHz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer | CG | MARTINI (v2.1) | DOPC | 1000 | — | 2.0 |

| DPPC | 1000 | — | 2.2 | |||

| DLPC | 1000 | — | 2.6 | |||

| Parallel dimer | CG | MARTINI (v2.1) | DOPC | 5000 | 98.4 | 1.3 |

| DPPC | 5000 | 99.2 | 7.9 | |||

| DLPC | 5000 | 91.6 | 7.4 | |||

| Antiparallel dimer | CG | MARTINI (v2.1) | DOPC | 5000 | 100 | 1.3 |

| DPPC | 5000 | 100 | 1.8 | |||

| DLPC | 5000 | 100 | 2.1 | |||

| Monomer | Atomistic | SemiRF | DMPC | 500 | 10.3 | |

| SemiRF2 | 150 | 19.5 | ||||

| SemiPME | 250 | 9.7 | ||||

| AniRF | 150 | 13.1 | ||||

| AniRF2 | 100 | 14.0 | ||||

| AniPME | 70 | 13.7 | ||||

| Concatenated | 1100 | 3.1 |

Both the experimental and atomistic simulation study were carried out at a P/L ratio of 1:100, lower than in our CG simulations (1:72 and 1:36), but it has been shown that in this range, concentration has no effect on QS (18). Since in the CG force field each bead represents four carbons, there is no difference between acyl chains with 18 and 20 (or 14 and 16) carbons. Acyl chains with five, four, and three coarse-grained beads correspond to 11Z-eicosenoyl (20 carbon atoms and one double bond), palmitoyl, and lauryl esters, respectively. Since experiments were done in DOPC, DMPC, and DLPC (18) bilayers, the comparison should take into account the limited resolution of the CG model.

Hydrophobic mismatch increases helical tilt and slows down the dynamics

To characterize the effect of hydrophobic mismatch on the peptide orientation, we calculated a number of structural features for the simulated systems: the hydrophobic thickness of the bilayer, the hydrophobic length of the peptides, the tilt and azimuthal angles (see Table 2). Small fluctuations in the peptide hydrophobic length are consistent with minor deformations of the helical secondary structure. The hydrophobic mismatch between WALP23 and a DPPC bilayer is negligible. The mismatch is small and negative in DOPC (the hydrophobic portion of the bilayer is thicker than the hydrophobic stretch of the peptide) and positive in DLPC.

Table 2.

Structural features of lipid bilayers in the presence of monomeric and dimeric WALP23 and tilt angle of the peptides calculated from coordinates

| System | Lipid | Bilayer hydrophobic thickness | Peptide hydrophobic length | % Dimer | Tilt peptide 1 | Tilt peptide 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer | DOPC | 2.92 (0.01) | 2.67 (0.01) | — | 11.4 (5.8, 0.2) | — |

| DPPC | 2.63 (0.01) | 2.62 (0.01) | — | 12.3 (6.5, 0.5) | — | |

| DLPC | 1.94 (0.01) | 2.57 (0.02) | — | 23.7 (8.8, 0.5) | — | |

| Parallel dimer | DOPC | 2.91 (0.01) | 2.66 (0.01) | 98.4 | 13.7 (6.4, 0.2) | 15.1 (6.4, 0.3) |

| DPPC | 2.63 (0.01) | 2.64 (0.01) | 99.2 | 16.3 (6.4, 0.3) | 15.9 (6.3, 0.2) | |

| DLPC | 1.94 (0.01) | 2.62 (0.02) | 91.6 | 24.2 (9.1, 0.9) | 22.8 (8.4, 0.8) | |

| Antiparallel dimer | DOPC | 2.91 (0.01) | 2.67 (0.01) | 100 | 14.2 (6.2, 0.6) | 16.5 (6.4, 0.2) |

| DPPC | 2.63 (0.01) | 2.64 (0.01) | 100 | 15.4 (6.4, 0.2) | 18.0 (6.6, 0.2) | |

| DLPC | 1.94 (0.01) | 2.61 (0.01) | 100 | 23.6 (7.9, 0.2) | 25.7 (9.3, 0.9) |

Dimer simulations were started from preassembled dimers. For the bilayer thickness and peptide length, the average values are reported with the standard error in parentheses. For the tilt angle, the average value is reported with the standard deviation and standard error in parentheses.

The average tilt increases with decreasing bilayer thickness (DOPC > DPPC > DLPC), as expected (see Fig. 1 A). However, the increase in tilt angle between DOPC and DPPC is very small. In contrast, when the mismatch is large and positive (in DLPC), the tilt increases significantly. These data are in good agreement with those of all-atom simulations: a tilt angle of ∼10° is observed with zero or negative mismatch, whereas when the positive mismatch increases, so does the tilt (23). This is also in agreement with previous predictions from continuum models (35).

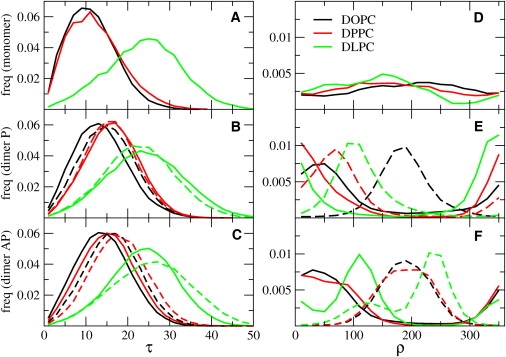

Figure 1.

Normalized distributions of tilt, τ (A–C), and azimuthal rotation, ρ (D–F), angles, in degrees, for simulations of monomers and preassembled parallel and antiparallel dimers, respectively. Simulation data for DOPC, DPPC, and DLPC are in black, red, and green, respectively. For the dimer simulations, the distributions for the first peptide are depicted with solid lines and those for the second with dashed lines. As in Table 2, all properties of dimers were calculated on the intact dimers only. (See online version for colors.)

The distribution of azimuthal rotation in the monomer simulations is shown in Fig. 1 D. The preference for a certain azimuthal angle is small in DOPC and DPPC (where the tilt angle is also small). Thanks to the extensive sampling, we could estimate the free energy difference between the most and least probable rotation angle (see Table S1). The value is less than thermal energy in both DPPC and DOPC, indicating that the peptide can rotate easily but that all rotations are not equally likely. The free energy difference between different rotational states is higher in DLPC (∼2 kT), where the helices are more tilted. The existence of preferential rotation angles leads to the nonequivalence of QS values for different alanines in the sequence, and is therefore consistent with experimental data (18). At the same time, we observe that the rotation of the peptide about its helical axis is fast compared to the experimental timescale. The rotational autocorrelation time is in the nanosecond timescale in all lipid bilayers (see Fig. S3). Rotation dynamics is faster in DOPC and DPPC than in DLPC. Fast rotation implies that only one signal should be observed for each alanine, which again is consistent with NMR experiments.

Monomer-dimer equilibrium is compatible with experimental QS data

We carried out 5-μs simulations of WALP23 dimers (starting from preassembled dimers) in the same lipid bilayers used for the monomers. Dimers with an antiparallel arrangement are stable in all lipids on the timescale of the simulations. On the other hand, parallel dimers are less stable and sometimes separate during the simulations (2–9% of the time in DOPC and DLPC, respectively).

The effect of dimerization on the tilt is small (see Fig. 1, B and C, and Table 2). The instantaneous tilt and rotation of the two peptides in the dimer are generally different, indicating an asymmetric arrangement of the helices. Although the average tilt of each helix is very similar after ∼5 μs, the average rotation is still different (see Table 2) and distributions of rotational angles have different shapes for each peptide (see Fig. 1, E and F). Moreover, the rotational dynamics is significantly slower than in the monomer (see Fig. S3). Both the increased rotational preference and the slower rotational dynamics depend on the presence of peptide-peptide interactions. Orientational distributions indicate that sampling is not sufficient to reach equilibrium (see Fig. S7) and raise an important question on the dimer dynamics: is the exchange dynamics sufficiently fast to yield a single signal for each alanine in the NMR spectrum? Slow exchange on the NMR timescale would lead to different QS values for alanines, which is not compatible with experimental results. To better understand the dynamics of WALP23 dimers, we carried out multiple simulations of dimers at lower concentration (1:72 P/L ratio, closer to experimental conditions). The peptides were separated at the beginning of the simulations to avoid bias toward particular structures. We simulated four replicas for each orientation (P and AP) in DLPC and DOPC, and each run lasted 10 μs. In all cases, we observed the formation of stable dimer within 3 μs (see Fig. S4 and Fig. S5), but there were few or no disaggregation-reaggregation events within 10 μs. Despite this, peptides in the dimers do exchange their orientation multiple times during the simulations (Fig. 2), indicating that exchange dynamics is faster than the NMR timescale (hundreds of microseconds). Simulations therefore predict that WALP23 dimers would give rise to only one average signal for each alanine.

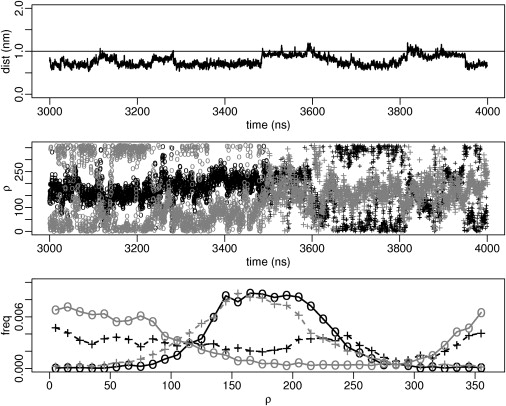

Figure 2.

Orientational exchange in dimers. (Upper) Peptide-peptide distance between centers of mass in a WALP23 dimer in DOPC as a function of simulation time (3000–4000 ns). (Middle) Azimuthal rotation of each peptide over the same time frame, with one peptide in black and the other in gray. The first half of the plot (3000–3500 ns) is shown with open circles and the other half (3500–4000 ns) with crosses. (Lower) Distribution of the azimuthal rotation calculated over the different time frames (3000–3500 ns and 3500–4000 ns) for each peptide. Colors and symbols follow the same rules as for the middle panel. The peptides exchange their orientation on a timescale of hundreds of nanoseconds, even if the dimer is very stable. All curves are taken from a dimer simulation (Fig. S4, AP4) started from two separated peptides.

Having analyzed the structure and dynamics of the dimers, we calculated the QS values (from the simulations started from the preassembled dimers (see Table 1)). The average deviation of the calculated QS from experimental values is very small in DOPC (∼1 kHz) for both the parallel and the antiparallel orientation. Deviations are systematically larger for the P dimer (7.4 and 7.9 kHz) compared to the AP one (1.8 and 2.1 kHz) in DPPC and DLPC. Averaging over both peptides always provides a better match with experimental data (see Fig. S2 and Fig. S6).

To confirm the possibility of an equilibrium between monomeric and dimeric forms of WALP23, we also evaluated the QS for a number of selected mixtures of monomer and P and AP dimers (see Table S2). In all cases, we find that some mixtures of monomeric and dimeric forms are in reasonable agreement with experimental data. In DOPC, any mixture between the monomer and P and AP dimers is compatible with experimental data. In contrast, in DPPC and DLPC, only mixtures of monomer and AP dimer give low deviations from experiments. In all the mixtures compatible with experimental data, the difference between the average QS for the monomer and the dimer is <2 kHz.

Discussion

Comparison between simulations and experiments

The extent of helix tilt for WALP peptides in lipid bilayers has been a matter of debate in the recent literature (36), due to discrepancies between results obtained with different experimental and computational techniques. An ATR-FTIR spectroscopy study first proposed moderate tilt angles (∼12° for WALP23 in DMPC) (16), but with a nonlinear relationship between the tilt and the extent of positive mismatch. Solid-state 2H NMR predicted increasing tilts upon increasing positive mismatch, but with very low values (∼5° for WALP23 in DMPC) (17,18). Very recently, a fluorescence spectroscopy study determined a tilt angle of 23.6° for WALP23 in DOPC (37)—a result that differs greatly from previous NMR studies. The authors were surprised to find a very modest increase in tilt (i.e., 24.8° in di-C16:1) upon going to a thinner bilayer. Moreover, no reliable result could be obtained in di-C14:1 lipids, possibly due to distortions of peptide structure. Obtaining the helical tilt from fluorescence techniques requires complex interpretations of experimental data and, notably, knowledge of the position of the probe relative to the helix axis. Despite the low resolution of the technique, this work suggests the existence of tilt angles larger than previously estimated, even in near-matching conditions.

In most computational studies, WALP peptides display larger tilt angles compared to solid-state 2H-NMR results. MD simulations provided values in the range 20–35° (20–24). This difference appears to be independent of the force field and other details of methods used in simulations. For example, in a recent study using the CHARMM force field, an angle of 28° was found for WALP23 in DMPC (38). A study using a CG approach with no sequence specificity gave tilt angles of 10–15°, lower than those reported in atomistic simulations (39,40). The average tilt angle found in our CG simulations is smaller than those reported from all-atom simulations of similar peptides under similar mismatch conditions, but still significantly larger than those reported from 2H-NMR experiments interpreted with the static GALA method.

Two recent studies explained the discrepancy between simulations and the GALA method (20,24) with averaging effects due to the fluctuations in peptide orientation. Due to nonlinear averaging of trigonometric functions, a peptide with a fluctuating rotation angle and a tilt angle of 30° can yield the same QS as a motionless peptide with a tilt of 5°. The same effect is also found in our work: for example, the tilt evaluated using the static GALA equation (using QS back-calculated from the simulations) is 1° in DOPC, although the value calculated from the coordinates is 10.4° (see Table S3). This highlights the need to take into account fluctuations in peptide orientation when analyzing solid-state NMR experiments.

Other works also emphasized the importance of fluctuations in the interpretation of PISEMA spectra (15N chemical shift versus 15N-1H dipolar coupling) (41–44), as well as 2H-NMR data. Esteban-Martin et al. evaluated the probability of all possible peptide orientations using an implicit potential based on the free energy of insertion of amino acids in a membrane (45). Only when they used the whole distribution of orientations could the experimental 2H QS be reproduced. The extent of tilt found by this method was rather high, e.g., 36° for WALP23 in DMPC. Alternatively, Strandberg et al. proposed to include fluctuations in the GALA method (25) by introducing Gaussian distributions for the tilt, τ, and/or rotation, ρ, in the GALA equation (Eq. 2). The widths of the Gaussian distributions (στ and σρ) were used, together with τ and ρ, as fitting parameters (determined by minimizing the root-mean-squared deviation between experimental values and those obtained from the GALA equation). Table 3 shows a comparison of the angles found by that method with those found in our simulations. The tilt predicted by our simulations matches within 5° the model that describes fluctuations of both τ and ρ (Model 6 in Strandberg et al. (25)). It is interesting that the agreement is good also for the azimuthal rotation.

Table 3.

Comparison of CG MD helical orientations with dynamic GALA model orientations

| Tilt (°) |

Rotation (°) |

RMSD (kHz) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG coord∗ | GALA ρ fluct† | GALA τ,ρ fluct‡ | CG coord∗ | GALA ρ fluct† | GALA τ,ρ fluct‡ | GALA ρ fluct† | GALA τ ρ fluct‡ | |

| DPPC | 12.3 | 115 | ||||||

| DMPC | 18 | 14 | 158 | 158 | 0.9 | 0.9 | ||

| DLPC | 23.7 | 34 | 29 | 155 | 143 | 143 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

CG MD helical orientations are from this study, and GALA model orientations are from Strandberg et al. (25). Note that we use here the original convention for the rotation (Gly1 as a reference), which corresponds to the values in parentheses in Table 2 of Strandberg et al. (25).

CG coord indicates the values obtained directly from the coordinates in our monomer CG MD simulations.

Fluctuations of rotation only (ρ) correspond to model 4 of Strandberg et al. (25).

Fluctuations of both tilt and rotation (τ,ρ) correspond to model 6 of Strandberg et al. (25).

Although the most probable values of tilt and rotation calculated from our simulations match well the results of Strandberg (25), our simulations raise the question of the suitability of the use of Gaussian distributions to describe the peptide motion, especially for the rotation about the helical axis. Previous all-atom simulations yielded complex distributions, including multimodal distributions, but it was not clear whether these were a result of insufficient sampling (24). The work reported here shows that the distributions of both τ and ρ generally present only one maximum (Fig. 1) but are not strictly Gaussian. This is particularly evident for the azimuthal angle, which has periodic distributions that are far from Gaussian.

We notice here that each QS value is determined by the precise shape of the distributions for τ and ρ, not by tilt and rotation dynamics (as long as they are faster than the experimental timescale; intermediate dynamics would broaden NMR signals and slow dynamics would result in multiple, possibly overlapping signals). Although peptide dynamics in our simulations is probably faster than in real systems (due to the smoother interactions in the CG force field (26,27)), this has no effect on the calculated QS values. When analyzing simulations, randomizing the order of the frames would yield the same QS.

Based on this work and on previous work by other groups (20,24,25,45), it is clear that different motional models (static rigid helices, dynamic rigid helices with some distribution of fluctuations and/or of aggregation states) can yield a good fit of 2H QS with different values of peptide tilt and rotation. Therefore, QS values are not sufficient to unambiguously determine peptide orientation and dynamics. The use of additional experimental data (for example, 15N solid-state NMR) seems a promising alternative. Koeppe and co-workers used 2H NMR and PISEMA to assess the orientation of the GWALP23 peptide (46). Their analysis did not take into account the possible fluctuations in the peptide orientation, and a rather small tilt was found (∼10° in DLPC). We note that the small tilt could also be the result of peptide aggregation (promoted by the high P/L ratio, 1:20). We also note that dynamic averaging could improve the fit of 15N NMR data (41). Recently, Milon and co-workers studied the orientation of WALP23 in DMPC using 2H-NMR QS together with 13C and 15N chemical shifts and 13C-15N dipolar couplings (47). Using a fitting procedure similar to dynamic GALA, i.e., including Gaussian or uniform distributions for tilt and rotation (as in works by Strandberg and co-workers (25,41)), those authors found a larger helical tilt, ∼21°, whereas the rotation (145°) was similar to previous results obtained with static GALA (18). To further validate our CG approach, it would be interesting to back-calculate these newly determined experimental observables (47) from the simulations. Work in this direction is ongoing.

The use of CG MD simulations provides a different, independent route for the prediction of orientation and dynamics of helical transmembrane segments. CG MD does not require any motional model and, being ∼3 orders of magnitude faster than atomistic simulations, allows for near-equilibrium sampling of molecular motions for monomeric peptides. Back-calculation of QS provides a simple way to validate CG MD results. Since QS depends only on the shape of τ and ρ distributions, possible (minor) alterations of peptide dynamics do not affect the accuracy of CG MD predictions.

WALP dimerization

Determining peptide aggregation in lipid bilayers is a challenge not only for simulation studies but also for experiments. Recent experimental studies indicate that WALP23 dimerization is strongly concentration- and phase-dependent. It has been shown via electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy that at low temperature, aggregates of WALP23 are present at a 1:100 P/L ratio when the lipids are in the gel phase, whereas no sign of aggregation is observed in the fluid phase (48). Fluorescence data on WALP23 suggest the presence of AP dimers at a P/L ratio of 1:25 and above (29). At a 1:36 ratio, it was possible to detect experimentally a low concentration of excimers (i.e., dimers) (49), whereas our simulations predict stable dimers. The discrepancy might be due to the CG force field overestimating the stability of the dimer. It could also be that the large pyrene probe (used in the fluorescence experiments) compromises the stability of the dimer.

In DPPC and DLPC, a combination of monomer and AP dimer give the best agreement with experimental results, whereas in DOPC all combinations of monomer and AP and P dimers give good agreement with experiments. Is the presence of dimers compatible with experimental results? Is it plausible to think of a monomer-dimer equilibrium? In 2H-NMR experiments on WALP23, each alanine gives rise to a single QS in the 2H-NMR spectrum, different from the other alanines (18). This requires that 1), not all rotation angles are equally probable; 2), if different aggregation states exist, the peptides must exchange on a timescale shorter than the 2H-NMR timescale (hundreds of microseconds); if this were not the case, the different species would give rise to multiple signals for each alanine. We verified that our simulations meet both conditions. Despite the great stability of the dimers, the exchange rates between different peptides in the dimers are fast enough to justify averaging the QS values (see Fig. 2 and Fig. S7). Moreover, QS values predicted by simulations for monomers and AP dimers are very similar (within 2 kHz or less)—in other words, monomers and dimers are predicted to have very similar 2H-NMR spectra. It is also possible that larger aggregates would form and contribute to the NMR signal. Further work to assess the structure and dynamics of other aggregation states is currently ongoing.

Simulations of WALP23 dimers suggest that the AP arrangement is more stable than the P arrangement, independent of the lipid bilayer. No disruption of the dimer is observed when the arrangement is AP, whereas the P dimer can fall apart and reform within the simulation timescale. The presence of AP dimer is compatible with FRET experiments and with previous computer modeling studies in vacuum (29,49). The greater stability of the AP dimer has been observed before in helix-helix association of transmembrane model peptides (29,49,50). Adjacent helices in membrane proteins also appear to prefer an AP orientation (51–53). The attractive electrostatic interaction between helix macrodipoles has been proposed to be at the origin of the preference for the AP orientation (29). In the case of our CG simulations, such dipoles are not present (no charges are present on the peptides) and other factors must contribute to the higher stability of the AP orientation. In the CG simulations, the greater stability of the AP over the P dimer can be related to the peptide-peptide Lennard-Jones energy, as shown in Fig. S8. In the absence of electrostatic interactions, the Lennard-Jones potential energy is the main contribution to dimer stability (lipid-peptide and lipid-lipid interactions being approximately equal in both arrangements). Due to its short-range nature, a more negative Lennard-Jones energy essentially reflects a higher number of close contacts between the peptides and therefore better surface complementarity (see Fig. 3, C and D).

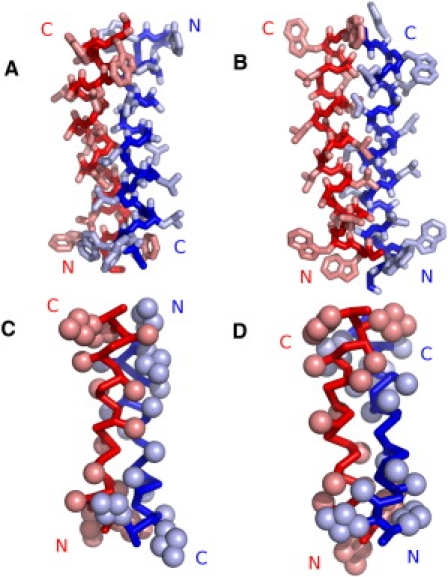

Figure 3.

Snapshot of dimers obtained by docking atomistic structures and from CG simulations. (A and B) Best AP (A) and P (B) dimers in terms of SC (SC scores of 367 and 278, respectively). (C and D) Snapshots of CG dimers (started from preassembled dimers) with the most favorable Lennard-Jones interpeptide energy in DOPC for AP (C) and P (D) orientations (−422.8 and −401.5 kJ mol−1, respectively). The backbone is rendered as a Cα trace and the side chains are drawn as spheres representing the CG beads. The radii of the beads have been scaled down to visualize the interdigitation of side chains. The different peptides in the dimers are colored blue and red. The orientation of the peptides is indicated by N and C labels. All snapshots were rendered with Pymol (54). (See online version for colors.)

To check whether a similar effect is also observed with an atomistic description, we carried out molecular docking calculations using an all-atom model. Electrostatic interactions were switched off, so that only surface complementarity (SC) was considered. Table 4 reports SC scores for the 10 most stable dimers. Clearly the AP arrangement yields structures with better SC, related to better packing of the side chains (see Fig. 3, A and B). We conclude that the preference for the AP orientation originates also from better SC, in addition to the helix macrodipole attraction. We note that despite the lower level of detail and the greater smoothness of the representation, the CG model appears to capture the better SC of the AP dimer shown in the atomistic docking calculations.

Table 4.

Surface complementarity score and orientation of the 10 best dimers

| Rank | SC score | AP | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 368 | x | |

| 2 | 311 | x | |

| 3 | 307 | x | |

| 4 | 284 | x | |

| 5 | 278 | x | |

| 6 | 274 | x | |

| 7 | 274 | x | |

| 8 | 272 | x | |

| 9 | 262 | x | |

| 10 | 260 | x |

Dimers were obtained using FTDock without electrostatic contributions. Higher scores indicate better surface complementarity. SC, surface complementarity; AP, antiparallel orientation; P, parallel orientation.

Conclusions

We presented coarse-grained simulations of the WALP23 peptide in monomeric form and in dimeric form with both parallel and antiparallel arrangements, in three different lipid bilayers at two different concentrations. We calculated different properties that can be compared to experiments, in particular 2H-NMR QS and metrics describing peptide orientation. The agreement with experimental QS is significantly improved compared with previous atomistic simulations, indicating that the extent of sampling is more important than atomic detail for the reproduction of experimental QS. The general trend of peptide orientation as a function of hydrophobic mismatch agrees well with predictions by continuum theory. Simulations also predict that mixtures of monomer and dimer species can provide good fits to experimental QS data. In dimers, SC appears to contribute significantly to the higher stability of the AP arrangement, as do electrostatic interactions between helical backbone dipoles.

It is known that the GALA analysis performed with different motional models provides different tilt and rotation angles. Our approach, on the other hand, does not require any assumption on the motion of the peptide, as the latter is predicted by the force field. CG MD simulation results can be validated by direct comparison of calculated with experimental QS values. Because calculated QS values depend only on the distributions of tilt and azimuthal rotation, the possible overestimation of peptide dynamics has no effect on the predicted QS. Finally, our results provide further validation of the MARTINI force field.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Walter Ash for providing molecular models of WALP dimers. L.M. and P.F.J.F. thank Catherine Etchebest and the group of Alain Milon for fruitful discussions.

This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). D.P.T. is an AHFMR Senior Scholar and CIHR New Investigator. P.F.J.F. dedicates this work to the memory of Professor A. M. Tamburro.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Lee A.G. How lipids affect the activities of integral membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1666:62–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nyholm T.K., Özdirekcan S., Killian J.A. How protein transmembrane segments sense the lipid environment. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1457–1465. doi: 10.1021/bi061941c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palsdottir H., Hunte C. Lipids in membrane protein structures. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1666:2–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora A., Tamm L.K. Biophysical approaches to membrane protein structure determination. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:540–547. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Groot H.J. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy applied to membrane proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:593–600. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loll P.J. Membrane protein structural biology: the high throughput challenge. J. Struct. Biol. 2003;142:144–153. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis J.H., Clare D.M., Bloom M. Interaction of a synthetic amphiphilic polypeptide and lipids in a bilayer structure. Biochemistry. 2002;22:5298–5305. [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Planque M.R., Killian J.A. Protein-lipid interactions studied with designed transmembrane peptides: role of hydrophobic matching and interfacial anchoring. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2003;20:271–284. doi: 10.1080/09687680310001605352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Killian J.A. Synthetic peptides as models for intrinsic membrane proteins. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis R.N., Zhang Y.P., McElhaney R.N. Mechanisms of the interaction of α-helical transmembrane peptides with phospholipid bilayers. Bioelectrochemistry. 2002;56:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5394(02)00012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White S.H., Wimley W.C. Hydrophobic interactions of peptides with membrane interfaces. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1376:339–352. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(98)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouritsen O.G., Bloom M. Mattress model of lipid-protein interactions in membranes. Biophys. J. 1984;46:141–153. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84007-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumas F., Lebrun M.C., Tocanne J.F. Is the protein/lipid hydrophobic matching principle relevant to membrane organization and functions? FEBS Lett. 1999;458:271–277. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Killian J.A. Hydrophobic mismatch between proteins and lipids in membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1376:401–415. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(98)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Planque M.R., Bonev B.B., Killian J.A. Interfacial anchor properties of tryptophan residues in transmembrane peptides can dominate over hydrophobic matching effects in peptide-lipid interactions. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5341–5348. doi: 10.1021/bi027000r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Planque M.R., Goormaghtigh E., Killian J.A. Sensitivity of single membrane-spanning α-helical peptides to hydrophobic mismatch with a lipid bilayer: effects on backbone structure, orientation, and extent of membrane incorporation. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5000–5010. doi: 10.1021/bi000804r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Özdirekcan S., Rijkers D.T., Killian J.A. Influence of flanking residues on tilt and rotation angles of transmembrane peptides in lipid bilayers. A solid-state 2H NMR study. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1004–1012. doi: 10.1021/bi0481242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strandberg E., Özdirekcan S., Killian J.A. Tilt angles of transmembrane model peptides in oriented and non-oriented lipid bilayers as determined by 2H solid-state NMR. Biophys. J. 2004;86:3709–3721. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.035402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Wel P.C., Strandberg E., Koeppe R.E., 2nd Geometry and intrinsic tilt of a tryptophan-anchored transmembrane α-helix determined by 2H NMR. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1479–1488. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73918-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esteban-Martín S., Salgado J. The dynamic orientation of membrane-bound peptides: bridging simulations and experiments. Biophys. J. 2007;93:4278–4288. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.113043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodyear D.J., Sharpe S., Morrow M.R. Molecular dynamics simulation of transmembrane polypeptide orientational fluctuations. Biophys. J. 2005;88:105–117. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Im W., Brooks C.L., 3rd Interfacial folding and membrane insertion of designed peptides studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6771–6776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408135102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandasamy S.K., Larson R.G. Molecular dynamics simulations of model trans-membrane peptides in lipid bilayers: a systematic investigation of hydrophobic mismatch. Biophys. J. 2006;90:2326–2343. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Özdirekcan S., Etchebest C., Fuchs P.F. On the orientation of a designed transmembrane peptide: toward the right tilt angle? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15174–15181. doi: 10.1021/ja073784q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strandberg E., Esteban-Martín S., Ulrich A.S. Orientation and dynamics of peptides in membranes calculated from 2H-NMR data. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3223–3232. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marrink S.J., Risselada H.J., de Vries A.H. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monticelli L., Kandasamy S.K., Marrink S.-J. The MARTINI coarse-grained force field: extension to proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:819–834. doi: 10.1021/ct700324x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kandt C., Ash W.L., Tieleman D.P. Setting up and running molecular dynamics simulations of membrane proteins. Methods. 2007;41:475–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sparr E., Ash W.L., Killian J.A. Self-association of transmembrane α-helices in model membranes: importance of helix orientation and role of hydrophobic mismatch. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:39324–39331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., Haak J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marrink S.J., Risselada J., Mark A.E. Simulation of gel phase formation and melting in lipid bilayers using a coarse grained model. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2005;135:223–244. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berendsen H.J.C., van der Spoel D., van Drunen R. GROMACS: a message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindahl E., Hess B., van der Spoel D. GROMACS 3.0: a package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. J. Mol. Model. 2001;7:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabb H.A., Jackson R.M., Sternberg M.J. Modelling protein docking using shape complementarity, electrostatics and biochemical information. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;272:106–120. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duque D., Li X.-j., Schick M. Molecular theory of hydrophobic mismatch between lipids and peptides. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:10478–10484. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holt A., Killian J.A. Orientation and dynamics of transmembrane peptides: the power of simple models. Eur. Biophys. J. 2010;39:609–621. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0567-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holt A., Koehorst R.B., Killian J.A. Tilt and rotation angles of a transmembrane model peptide as studied by fluorescence spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2258–2266. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Im W., Lee J., Rui H. Novel free energy calculations to explore mechanisms and energetics of membrane protein structure and function. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1622–1633. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venturoli M., Smit B., Sperotto M.M. Simulation studies of protein-induced bilayer deformations, and lipid-induced protein tilting, on a mesoscopic model for lipid bilayers with embedded proteins. Biophys. J. 2005;88:1778–1798. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sperotto M.M., May S., Baumgaertner A. Modelling of proteins in membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2006;141:2–29. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Esteban-Martín S., Strandberg E., Salgado J. Influence of whole-body dynamics on 15N PISEMA NMR spectra of membrane proteins: a theoretical analysis. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3233–3241. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Page R.C., Kim S., Cross T.A. Transmembrane helix uniformity examined by spectral mapping of torsion angles. Structure. 2008;16:787–797. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi L., Cembran A., Veglia G. Tilt and azimuthal angles of a transmembrane peptide: a comparison between molecular dynamics calculations and solid-state NMR data of sarcolipin in lipid membranes. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3648–3662. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Straus S.K., Scott W.R.P., Watts A. Assessing the effects of time and spatial averaging in 15N chemical shift/15N-1H dipolar correlation solid state NMR experiments. J. Biomol. NMR. 2003;26:283–295. doi: 10.1023/a:1024098123386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esteban-Martín S., Giménez D., Salgado J. Orientational landscapes of peptides in membranes: prediction of 2H NMR couplings in a dynamic context. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11441–11448. doi: 10.1021/bi901017y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vostrikov V.V., Grant C.V., Koeppe R.E., 2nd Comparison of “polarization inversion with spin exchange at magic angle” and “geometric analysis of labeled alanines” methods for transmembrane helix alignment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12584–12585. doi: 10.1021/ja803734k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holt A., Rougier L., Milon A. Order parameters of a transmembrane helix in a fluid bilayer: case study of a WALP peptide. Biophys. J. 2010;98:1864–1872. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scarpelli F., Drescher M., Huber M. Aggregation of transmembrane peptides studied by spin-label EPR. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:12257–12264. doi: 10.1021/jp901371h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sparr E., Ganchev D.N., de Kruijff B. Molecular organization in striated domains induced by transmembrane α-helical peptides in dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine bilayers. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2–10. doi: 10.1021/bi048047a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yano Y., Takemoto T., Matsuzaki K. Topological stability and self-association of a completely hydrophobic model transmembrane helix in lipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3073–3080. doi: 10.1021/bi011161y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bowie J.U. Helix packing in membrane proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;272:780–789. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gimpelev M., Forrest L.R., Honig B. Helical packing patterns in membrane and soluble proteins. Biophys. J. 2004;87:4075–4086. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walters R.F., DeGrado W.F. Helix-packing motifs in membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13658–13663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605878103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeLano W.L. DeLano Scientific; Palo Alto, CA: 2002. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.