Abstract

We are investigating the influence of the converter and relay domains on elementary rate constants of the actomyosin cross-bridge cycle. The converter and relay domains vary between Drosophila myosin heavy chain isoforms due to alternative mRNA splicing. Previously, we found that separate insertions of embryonic myosin isoform (EMB) versions of these domains into the indirect flight muscle (IFM) myosin isoform (IFI) both decreased Drosophila IFM power and slowed muscle kinetics. To determine cross-bridge mechanisms behind the changes, we employed sinusoidal analysis while varying phosphate and MgATP concentrations in skinned Drosophila IFM fibers. Based on a six-state cross-bridge model, the EMB converter decreased myosin rate constants associated with actin attachment and work production, k4, but increased rates related to cross-bridge detachment and work absorption, k2. In contrast, the EMB relay domain had little influence on kinetics, because only k4 decreased. The main alteration was mechanical, in that work production amplitude decreased. That both domains decreased k4 supports the hypothesis that these domains are critical to lever-arm-mediated force generation. Neither domain significantly influenced MgATP affinity. Our modeling suggests the converter domain is responsible for the difference in rate-limiting cross-bridge steps between EMB and IFI myosin—i.e., a myosin isomerization associated with MgADP release for EMB and Pi release for IFI.

Introduction

Muscle contraction is driven by the conversion of chemical energy, MgATP, to force and motion by myosin's cyclic interaction with actin. Force and motion are thought to be dependent on the rotation of the light chain domain, the lever arm, relative to the catalytic domain (1–4). How this rotation occurs is not well understood. The position of the lever arm has been linked to different biochemical states of the cross-bridge cycle, but its position must also be influenced by the conformational changes of different structural elements within the myosin molecule (5,6) and by mechanical load on myosin (7–9). These structural elements must also be responsible for setting differences in myosin's force-generating capability, velocity of actin movement, and myosin's responsiveness to load. These properties help endow muscle fiber types with specific shortening velocities or differences in oscillatory work and power-generating properties.

Two myosin domains proposed to be critical for the rotation of the lever arm are the converter and relay domains (Fig. 1). These domains are likely important for myosin intramolecular communication. The relay is proposed to be involved in at least two pathways (10). One involves linking the nucleotide-binding site, through switch 2, to the actin-binding site. The other pathway, which involves switch 2, the relay, and the converter, links the myosin active site to the lever arm. A conformational kinking of the relay, predicted from dynamic simulations linking pre- and postpower stroke crystal structures, is thought to be critical for rotating the lever arm through a direct link between the converter and relay domains (5). The converter is proposed to move with the lever arm and be a major compliant element whose stiffness influences rates of cross-bridge conformational changes (11–13).

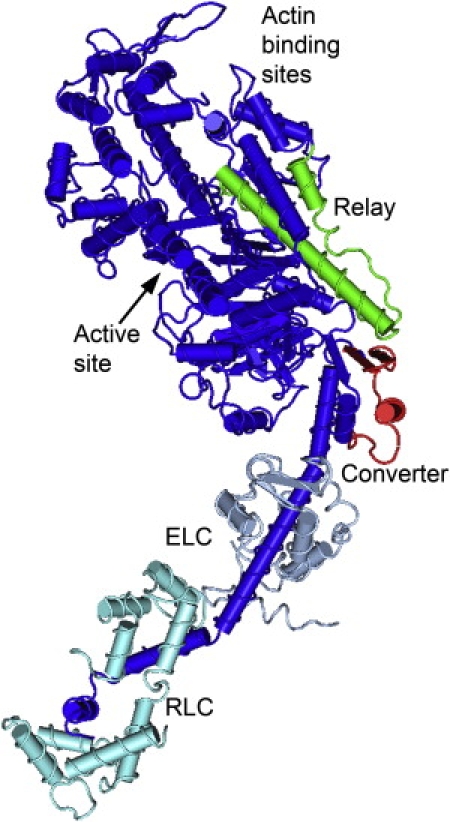

Figure 1.

Location of the Drosophila relay and converter domains. The converter domain (exon 11, red) and the relay domain (exon 9, green) are mapped onto the chicken myosin S1 structure (blue) (adapted from PDB structure 2MYS). Only five relay amino acids are changed by inserting the EMB version of the relay into IFI. Most of the changes are located at or near the end of the relay that is thought to interact with the converter (44). In contrast, 24 of 40 amino acids are changed when the EMB converter replaces the IFI converter (16). These amino acids changes are spread throughout the converter.

We have been investigating the importance of the converter and relay in setting functional differences between myosin and muscle fiber types using the Drosophila system. All Drosophila muscle myosin isoforms are produced from one gene through alternative splicing of its messenger RNA (14,15). Four domains in the myosin head have alternative versions. We have systematically exchanged these four regions between the superfast indirect flight muscle myosin isoform (IFI) and the slower embryonic myosin isoform (EMB) isoform, and transgenically expressed the resultant chimeric myosins in Drosophila indirect flight muscle (IFM) (16–18). Two of these exchanges involved the alternative exons that encode the relay, exon 9 and converter, exon 11 (16,19,20). The IFM fibers can be dissected from the fly and mechanically evaluated on skinned fiber mechanics rigs (21).

We previously found that the converter produces the greatest difference in muscle mechanical properties of the four alternative S-1 domains studied. The converter drastically affected power production levels and muscle kinetics (16). At the molecular level, it exhibited a large effect on actin motility velocity. However, transient kinetics studies in solution did not support our hypothesized cross-bridge mechanism of the converter varying ADP release rate because no correlations were observed with myosin MgADP release rates (22). Exchanging the EMB relay domain into IFI decreased power generation (19). The exchange did not affect in vitro actin motility or MgATPase rates (23), leading to the hypothesis that the relay influences myosin's kinetic responsiveness to load (19).

To determine cross-bridge level kinetic mechanisms by which the converter and relay domains exert their influence on muscle function, we employed sinusoidal analysis and a six-state cross-bridge model (Fig. 2) (24). The results are particularly revealing for very fast myosin cross-bridge mechanisms, because our recent research suggests that the fastest known muscle myosin, IFI, appears to have an unusual rate-limiting step for the cross-bridge cycle during sinusoidal work production (25). Our modeling suggests that for very fast myosins, a step associated with Pi release may become rate-limiting rather than one associated with MgADP release. Slower muscle myosins are thought to be limited by an isomerization associated with MgADP release during work production (26). We have proposed that because superfast myosins needs to detach extremely rapidly from actin, the rate of MgADP release is increased to the extent that velocity becomes limited by earlier steps of the cycle, perhaps those associated with Pi release (25). Another possibility, based on our observation that IFI has extremely low MgATP affinity (25) and recent transient kinetic studies of fast rat skeletal muscle MgADP release rate (27), is that MgATP binding and/or the subsequent myosin detachment from actin are limiting. Thus, investigating how the EMB converter and relay help set IFI muscle kinetics should provide insight into critical rate constants for setting myosin speed, particularly very fast myosin isoforms.

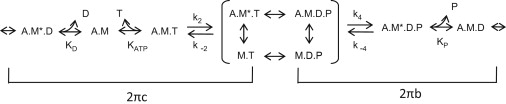

Figure 2.

Cross-bridge scheme where M is myosin, A is actin, T is MgATP, D is MgADP, and P is phosphate. The asterisk signifies a second conformational state. For conceptual purposes, the primary transitions that influence 2πb and 2πc when a myosin isomerization between Pi and ADP release is rate-limiting are bracketed. The complete relationship of the elementary rate constants and affinity constants to 2πb and 2πc for IFM fibers has been fully described (see Supporting Information in (25)).

We derived elementary cross-bridge rate constants by varying MgATP and phosphate concentrations while performing sinusoidal analysis on IFM-expressing myosin with either the EMB converter exchanged into IFI myosin, IFI-EC or the EMB relay exchanged into IFI myosin, IFI-9b. In general, the decrease in power generation caused by the EMB converter was only due to altering rates of cross-bridge kinetic steps. The EMB relay only slightly influenced myosin kinetics. Most of its influence on power resulted from decreasing the amplitude of work production. We found that the EMB converter speeds up rates of cross-bridge steps associated with actin detachment and work absorption, k2 and decreases rate constants associated with actin attachment and work production, k4. The relay slightly decreased k4. Neither domain significantly influenced IFI's association constant for MgATP. Based on a six-state cross-bridge model interpretation (24), the converter is most likely responsible for the difference in rate-limiting steps during oscillatory work production between the faster IFI and slower EMB myosin isoforms.

Methods

Exon 9 and 11 transgenic fly lines

Cloning and construction of IFI (also referred to as pWMHC2), IFI-EC and IFI-9b transgenes were described previously (16,23,28). The transgenes were crossed into a Drosophila background, Mhc10, that does not produce any myosin in its IFM or jump muscles, thus only the transgenic myosin is expressed in the IFM fibers we evaluated. Because at least two independently generated lines of all the mutants have been previously characterized (16,19), we only evaluated one line of each IFI chimera.

Mechanics protocol

Preparation and mechanical evaluation of fibers was performed as previously described (19). To evaluate the mechanical and kinetic response to Pi concentration, the muscle was activated by a complete exchange of relaxing solution with activating solution. Pi concentration was increased by exchanging predetermined amounts of a 20 mM Pi activating solution (MgATP concentration for the Pi experiments was 13 mM) that was adjusted to maintain a constant ionic strength of 260 mM using the equations of Godt and Lindley (29). To evaluate the response to changes in [MgATP], 0 mM MgATP, and 20 mM MgATP, activating solutions were made. Appropriate amounts of 0 or 20 mM MgATP activating solutions were exchanged into the 30-μL bathing solution bubble to achieve the desired MgATP concentration. After each Pi and MgATP concentration sequence, the bathing solution was returned to the starting level of Pi or MgATP concentration to determine whether fiber performance degraded. If power generation dropped by >10%, the data from that fiber was not used.

Derivation of muscle apparent and cross-bridge elementary rate constants

Sinusoidal analysis was performed to measure complex modulus, elastic modulus, viscous modulus, work, and power, as previously described (19,30). For each MgATP or Pi concentration, the complex moduli from every fiber was fitted to a three-term equation (25,31) by following the methodology of Kawai and Brandt (24),

where f is the applied frequency of oscillation (0.5–650 Hz), i is the square root of −1, α is defined as 1 Hz, and k is a unitless exponent. The first term (A) reflects the viscoelastic properties of passive structures within the fiber, whereas the second and third terms (B and C) reflect cross-bridge-dependent processes (changes in dynamic stiffness moduli due to the strain-sensitivity of cross-bridge states) that are exponential in the time domain. Processes B and C appear as hemispheres in the Nyquist plot with characteristic frequencies b and c (see Swank et al. (25); their Fig. 4 and their Supporting Information). In the time domain, these frequencies correspond to rate constants 2πb and 2πc. Varying [Pi] or [MgATP] alters the steady-state distribution of cross-bridges states, a shift observed as changes in 2πb and 2πc values (24). See Supporting Material for an error analysis of our 2πc determination.

The cross-bridge kinetic constants for each fiber type were derived by fitting algebraic expressions that relate muscle apparent rate constants to elementary rate constants of the myosin cross-bridge cycle based on a six-state model (Fig. 2) (24,32). Because the apparent rate constants are more accurately related to cross-bridge rate constants as a sum, 2πb + 2πc, and product, 2πb × 2πc, in the steady-state solution of the six state cross-bridge scheme (25), we plotted both sum and product versus [MgATP]. We fit the plots with Eqs. 12 and 13 from either Scheme 1 or 2 (described in Swank et al. (25); their Fig. 7 and their Supporting Information). Both schemes end up producing the same equations for fitting apparent rate constants versus [MgATP].

The elementary rate constant values are more accurate when derived from fits of sum and product than the simpler method of fitting 2πb versus [Pi] and 2πc versus [MgATP]. The simpler method is only valid if the muscle detachment kinetics are much faster than the attachment kinetics (i.e., k2 >> k4), or in terms of the muscle apparent rate constants, when 2πb and 2πc are well separated in value (see Swank et al. (25); their Eqs. 11–15 and their Supporting Information). This simplification is not valid for IFI and IFI-9b. However, for IFI-EC, this simplifying assumption is valid, and we can thus fit 2πb versus [Pi] to calculate the phosphate association constant (Kp) and the actin attachment rate constants, k4 and k−4 (33).

Results

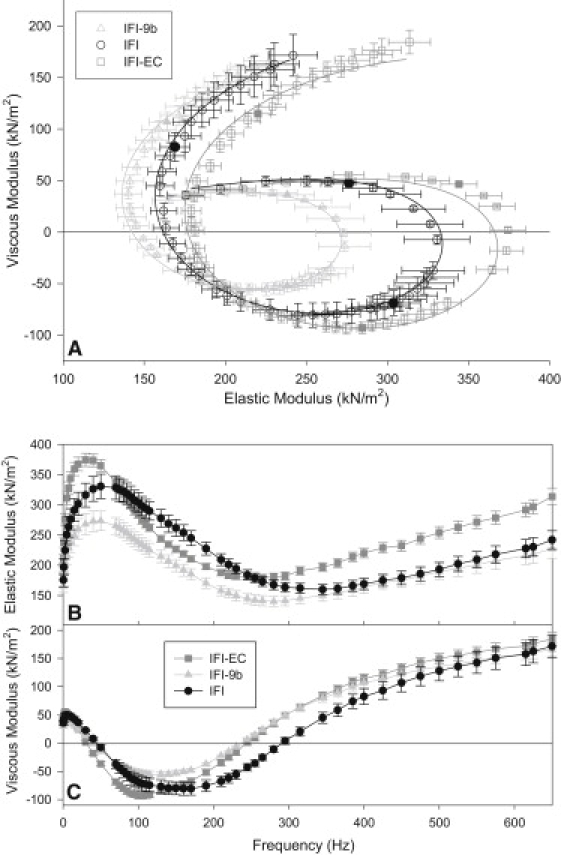

Using small amplitude sinusoidal analysis, we measured the complex stiffness of IFM fibers expressing IFI, IFI-EC, and IFI-9b transgenic myosins. At 12.5 mM MgATP, well above the concentration of MgATP where power generation saturates (25), the EMB converter and EMB relay both substantially alter IFM fiber's complex stiffness, but in different ways (Fig. 3). The EMB converter caused an increase in elastic stiffness (modulus) at high and low frequencies, but a decrease from 80 to 200 Hz (Fig. 3 B), which includes the wing-beat frequency of Drosophila at 15°C, ∼150 Hz. The EMB converter had no significant influence on the amplitude of the viscous modulus at low or high frequencies, but between 200 and 400 Hz, the viscous modulus amplitude became more negative than IFI (Fig. 3 C). The EMB relay had almost the opposite effect, compared to the EMB converter. The EMB relay decreased elastic stiffness compared to the IFI control at intermediate frequencies, but was not different at high and low frequencies (Fig. 3 B). The EMB relay caused the viscous modulus amplitude to be more positive in value at most work-producing frequencies (negative viscous modulus) and at higher frequencies up to ∼400 Hz (Fig. 3 C).

Figure 3.

(A) Complex moduli of three transgenic IFM fiber types. Frequencies used are as follows: 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 70, 75, 80, 85, 90, 95, 100, 105, 110, 115, 130, 140, 150, 160, 170, 190, 210, 220, 230, 245, 255, 265, 280, 295, 315, 345, 365, 385, 400, 425, 450, 475, 500, 525, 550, 575, 615, 625, and 650 Hz. (Solid symbols) 10, 100, and 400 Hz. The frequency with the most negative viscous modulus value is fwmax. Data points were fit with the complex modulus equation (see Methods) to yield the curve fits shown and data in Table 1. The data were obtained in activating solution with 12.5 mM MgATP and 0 mM Pi, 15°C. N = 6 for IFI, N = 7 for IFI-EC and IFI-9b. (B) Elastic modulus (instantaneous stiffness) as a function of frequency for all three IFM fiber types. (C) Viscous modulus as a function of frequency for all three IFM fiber types.

Small amplitude work and power generation

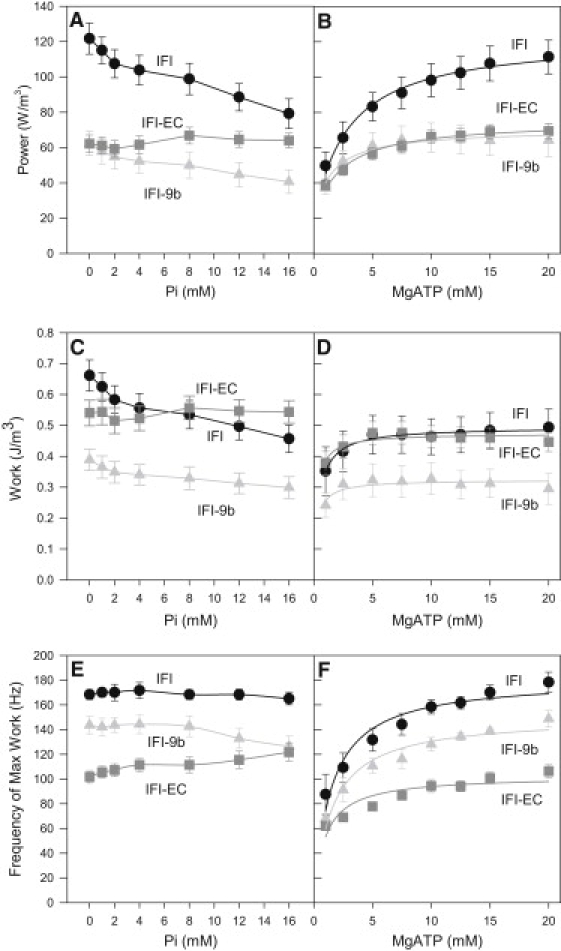

Both the EMB relay and converter caused large and similar decreases in IFM power generation (except at high Pi concentrations) by ∼50% compared to IFI fibers (Fig. 4, A and B). However, the two chimeric fibers differed in the amount of work they could produce. Expressing IFI-9b in IFM reduced work production to 60% of IFI, while the IFI-EC did not significantly decrease work production (Fig. 4, C and D).

Figure 4.

Power generated by transgenic IFM fiber types as a function of (A) phosphate and (B) MgATP concentrations. Work generations by three transgenic IFM fiber types as a function of (C) phosphate and (D) MgATP concentrations. Effect of (E) phosphate and (F) MgATP concentrations on the frequency at which maximum work (fwmax) is generated. MgATP concentration for the phosphate experiments was 13 mM, and Pi concentration was near zero for the MgATP experiments. 15°C. Mean ± SE. N = 6 for IFI, N = 7 for IFI-EC and IFI-9b.

The influence of [Pi] on work and power amplitude of IFI and IFI-9b fibers was very similar. Increasing [Pi] decreased power and work production (Fig. 4, A and C). At 16 mM Pi, power and work generation was 70% of the power and work at 0 mM Pi. In contrast, IFM expressing IFI-EC was not responsive to changes in [Pi]. No changes in power or work amplitude for IFI-EC occurred in response to increasing [Pi]. The response of the two chimeras and control fibers to [MgATP] all showed increasing power and work amplitudes with increasing [MgATP] (Fig. 4, B and D).

Both substitutions slowed myosin kinetics, but the EMB converter effect was much greater. IFI-EC's frequency at which maximum work (fwmax) was generated decreased to 60% of IFI fwmax (Fig. 4, E and F) at most MgATP and Pi concentrations. In contrast, IFI-9b fwmax was only decreased by a small amount, to 84% of IFI fwmax. Thus, the decrease in power generation by IFI-9b fibers was primarily due to a decrease in work generation with a small contribution from kinetics, whereas in IFI-EC fibers, the decrease in power appears exclusively driven by cross-bridge kinetics.

A nearly opposite kinetic response of the IFM fibers to [Pi] was observed from the EMB relay substitution compared to the EMB converter substitution. There was no change, or perhaps a slight decrease, in fwmax with increasing [Pi] for IFI and IFI-9b (Fig. 4 E). In contrast, IFI-EC fwmax displayed a slight upward trend with increasing [Pi] (Fig. 4 E). Fwmax of all three fiber types increased with increasing [MgATP] (Fig. 4 F).

Muscle apparent rate constants

We determined the influence of the converter and relay on muscle apparent rate constants using the complex stiffness fitting method and model employed by Kawai and Brandt (24), which we have refined for Drosophila IFM (25). We fit individual fiber's complex moduli (plotted as Nyquist plots; see Fig. 3) with our complex modulus equation (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material for representative plots showing the quality of the fits at high and low MgATP and Pi concentrations). Under conditions where maximum power is produced, 12.5 mM MgATP and 0 mM Pi (Table 1), the EMB converter had no effect on A, but decreased B and C (Table 1). The converter decreased IFI's apparent rate constant for work production, 2πb, while increasing the apparent rate constant for work absorption, 2πc. Substituting the EMB relay had no effect on A, but it decreased B and C amplitudes and decreased 2πb. It had no effect on 2πc compared to IFI values (Table 1).

Table 1.

Apparent rate constants and parameters of exponential processes for three transgenic fiber types under maximal power-generating conditions, 12.5 mM MgATP and 0 mM Pi

| A, kN/m2 | k | B, kN/m2 | 2πb s−1 | C, kN/m2 | 2πc s−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFI | 174 ± 17 | 0.150 ± 0.007 | 1877 ± 286 | 1846 ± 88 | 1680 ± 274 | 2499 ± 107 |

| IFI-EC | 185 ± 10 | 0.122 ± 0.006∗ | 563 ± 84∗ | 760 ± 44∗ | 469 ± 66∗ | 3165 ± 213∗ |

| IFI-9b | 139 ± 12 | 0.137 ± 0.003 | 898 ± 97∗ | 1463 ± 63∗ | 814 ± 105∗ | 2405 ± 57 |

The values were obtained under maximum power generating conditions at 12.5 mM MgATP and 0 mM Pi. The complex moduli were fit with the equation Y(f) = A (2π if/α)k – B if/(b +if) + C if/(c+if), where f is the applied frequency of oscillation (0.5–650 Hz), i is the square-root of −1, α is defined as 1 Hz, and k is a unitless exponent. Mean ± SE, N = 6 for IFI, N = 7 for IFI-EC and IFI-9b.

Statistically different from IFI, Student's t test (p < 0.05).

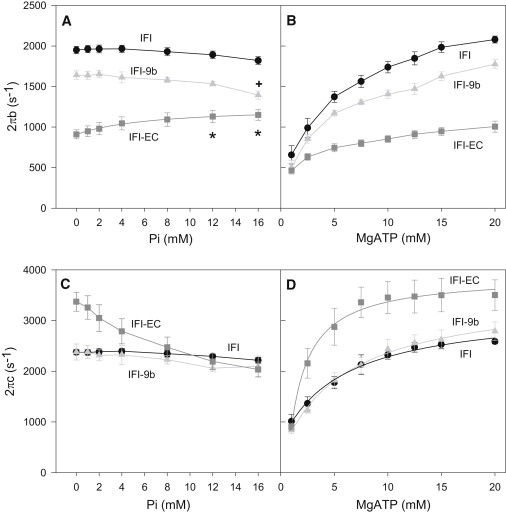

Converter's influence on apparent rate constants

IFI-EC 2πb values were much lower than the corresponding IFI values at all MgATP and Pi concentrations, more than twofold under some conditions (Fig. 5, A and B). Therefore, the decrease in IFI-EC muscle kinetics, fwmax, is principally due to a decrease in the rate of work producing cross-bridge transitions. IFI-EC 2πb rates increased with increasing [Pi] compared to IFI's flat or slightly decreased response (Fig. 5 A). IFI-EC 2πb increased with increasing [MgATP], but not nearly as much as IFI or IFI-9b (Fig. 5 B).

Figure 5.

The response of sinusoidal apparent rate constant 2πb to (A) phosphate and (B) MgATP concentrations. The response of sinusoidal apparent rate constant 2πc to (C) phosphate and (D) MgATP concentrations. MgATP concentration for the Pi experiments was 13 mM, and Pi concentration was near zero for the MgATP experiments. The IFI-EC curve in panel A was fit with a Scheme 2 derived fit (25), 2πb = k4+(k−4∗ (Kp∗P))/(1+Kp∗P) where P = [phosphate], Kp = affinity constant for phosphate. Other plots in panel A were not fit with an equation because their responses were essentially flat with a slight decrease at higher Pi concentrations due to competition between Pi and MgATP for the A.M.D state. This competitive inhibition likely also attenuates the slope of the IFI-EC curve. Curves in panels B and C were not fit. Curves in panel D were fit with equations relating [MgATP] to apparent rate constant 2πc. These equations are identical whether derived from Scheme 1 or 2: 2πc = (k2∗KT∗T)/(1+KT ∗T) + k−2. 15°C. Mean ± SE. N = 6 for IFI, N = 7 for IFI-EC and IFI-9b. (Star) Statistically different from 0 and 1 mM Pi IFI-EC values (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05). (Cross) Statistically different from 0, 1, and 2 mM Pi IFI-9b values (one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05).

IFI-EC 2πc values (set by work absorbing cross-bridge transition rates) were similar to IFI rates at the lowest tested [MgATP], but IFI-EC 2πc rates increased with [MgATP] more than IFI 2πc rates, becoming 1.5-fold higher than IFI 2πc at 20 mM MgATP (Fig. 5 D). Addition of Pi decreased IFI-EC 2πc (Fig. 5 C). By 8 mM Pi, IFI-EC 2πc was nearly identical to IFI 2πc and remained nearly identical up to our highest tested concentration, 16 mM Pi. Thus, rates of cross-bridge work absorbing transitions are faster in IFI-EC fibers than IFI except at high Pi concentrations.

Relay's influence on apparent rate constants

The EMB relay decreased 2πb, but not 2πc (Table 1 and Fig. 5). IFI-9b 2πb values were ∼85% of IFI values at almost all Pi and MgATP concentrations, except at very low MgATP concentrations where the values were similar. These values suggest that the slightly slower IFI-9b muscle kinetics, fwmax, are due to work-producing steps of the cross-bridge cycle and not work-absorbing steps. IFI and IFI-9b 2πb rates showed an initial flat response to increasing [Pi]. The response of 2πb slightly decreased at higher [Pi], likely due to competition with MgATP for the actomyosin rigor state. Both IFI and IFI-9b 2πc rates increased similarly with increasing [MgATP] (Fig. 5 D).

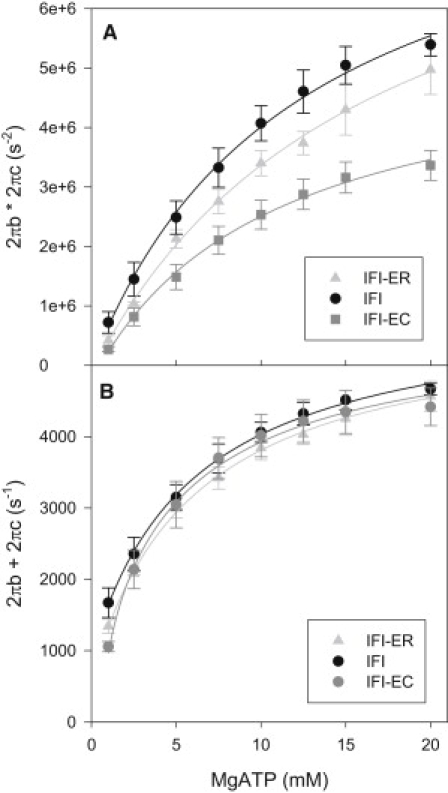

Cross-bridge rate constants from 2πb × 2πc and 2πb + 2πc versus [MgATP]

To determine elementary cross-bridge rate constants from sinusoidal analysis, we used algebraic derivations that relate muscle apparent rate constants, 2πb and 2πc, to affinity and rate constants of a six-state cross-bridge scheme (Fig. 2). We fitted the sum and product of 2πb and 2πc versus [MgATP] (Fig. 6). This is more accurate than separately fitting 2πb versus [Pi] and 2πc versus [MgATP] because fitting apparent rate constants individually requires a simplifying assumption, that 2πc >> 2πb (24). This simplifying assumption is likely not valid for two of the three fiber types as the difference between 2πb and 2πc values is low for IFI and IFI-9b. For example, at 20 mM MgATP, IFI 2πb is ∼2100 s−1 and 2πc ∼2400 s−1 (Fig. 5, B and D). Thus, we used the full equations described in the legend of Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

The response of (A) 2πb × 2πc and (B) 2πb + 2πc to [MgATP] for three transgenic IFM fiber types. The equations used to fit the curves were 2πb + 2πc = B/(1+(1/KT∗T)) + A where T = [MgATP], KT = affinity constant for MgATP, A = k-2 + k4+ k-4 and B = k2, and 2πb × 2πc = C/(1+(1/KT∗T)) + D where C = k2∗(k4+k-4) and D = k-2∗k-4. The same equations result from derivations based on either Scheme 1 or 2 (25). Mean ± SE. N = 6 for IFI, N = 7 for IFI-EC and IFI-9b.

Both the EMB relay and converter caused decreases in k4, the attachment to actin and work production portion of the cross-bridge cycle (Table 2). When compared to IFI, the value of k4 for IFI-EC decreased 45%, while IFI-9b only decreased 10%. The forward detachment rate constant, k2, was significantly increased 1.25-fold by the EMB converter, while the EMB relay did not show a significant effect on detachment rate. The affinity for MgATP (KATP) was not significantly changed by either the EMB relay or the EMB converter, suggesting that neither the converter nor relay is responsible for the much greater ATP affinity of EMB fibers compared to IFI fibers (25). The value k−4 cannot be accurately calculated (the values are near zero) from the MgATP data because Pi was not included in the bathing solution when we varied [MgATP]. Pi was excluded in order to minimize any competition of Pi with MgATP for the rigor (A.M.) state. Thus, the reversal of that step is highly unlikely to occur with very little Pi present (except for minor amounts from myosin's hydrolysis of MgATP) to bind to the ADP-bound (A.M.D) state. Another possible method to determine k−4 could have been to fit 2πb × 2πc and 2πb + 2πc versus [Pi]. However, we could not fit IFI and IFI-9b [Pi] plots due to the insensitivity of their apparent rate constants to [Pi].

Table 2.

Kinetic constants of the elementary steps associated with work-producing cross-bridge attachment (k4, and k−4) and work-absorbing cross-bridge detachment (k2 and k−2)

| Constants | Units | IFI | IFI-EC | IFI-9b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KATP | mM−1 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.26 ± 0.03 |

| k2 | s−1 | 4368 ± 210 | 5612 ± 402∗ | 4130 ± 157 |

| k−2 | s−1 | 669 ± 117 | 1401 ± 283∗ | 692 ± 134 |

| KP | mM−1 | NA | 0.15 ± 0.05† | NA |

| k4 | s−1 | 1720 ± 56 | 1072 ± 64∗ | 1564 ± 61∗ |

| k−4 | s−1 | ND | 346 ± 21† | ND |

| KATPk2 | μM−1 s−1 | 1.22 ± 0.06 | 1.79 ± 0.09∗ | 1.07 ± 0.04 |

KATP and KP are MgATP and Phosphate association constants, respectively. Most values were calculated by fitting apparent rate constants 2πb × 2πc versus [MgATP] and 2πb + 2πc versus [MgATP] with equations (see legend for Fig. 6) derived from a six-state cross-bridge model (details of the equation derivations are in Swank et al. (25), their Supporting Information). Mean ± SE, N = 6 for IFI, N = 7 for IFI-EC and IFI-9b. Temperature, 15°C, NA, not available as these curves could not be fit (see Fig. 5 legend). ND, not determined due to low [Pi] (see Results).

Statistically different from IFI, Student's t test (p < 0.05).

Calculated with Scheme 2 (25) derived fit, 2πb = k4 + (k−4∗ (Kp∗P))/(1+Kp∗P) where P = [phosphate], Kp = affinity constant for phosphate.

Rate constants from 2πb versus [Pi] and 2πc versus [MgATP]

We can calculate k-4, k4, and Pi affinity, KP, from the 2πb versus [Pi] data if the data are not essentially a flat line, and 2πb and 2πc are well separated in value. These conditions were present in the data of IFI-EC fibers. Using Scheme 2 from Swank et al. (25), we found that KP = 0.15 ± 0.05 mM−1, k4 = 906 ± 48 s−1, and k−4 = 346 ± 21 s−1. Typical fast muscle values are ∼0.2 mM−1 for Pi affinity (33). Comparing KATP and Kp suggests that MgATP affinity is only twice that of IFI-EC Pi affinity. The value k4 from this fit is ∼90% of the k4 value derived from fitting the combined response to [MgATP] (Table 2). Fitting IFI 2πb or IFI-9b 2πb versus [Pi] is not possible because these are essentially straight lines, as predicted when Pi release is rate-limiting (25).

To determine whether an alternative method of calculating k2, k−2, and KATP would give qualitatively similar results, we derived these values using 2πc versus [MgATP] (33). The k2, k−2, and KATP values from 2πc versus [MgATP] fits for IFI-EC were quantitatively different, calculated at 10% less than the values shown in Table 2. For IFI and IFI-9b, the values were ∼40% less. However, the qualitative relationships did not change (e.g., IFI-EC k2 value was still greater than both IFI-9b and IFI k2 values). The reason for the greater difference in values from the two methods for IFI and IFI-9b is most likely that 2πb and 2πc are not well separated in value for these two fiber types, while 2πb and 2πc are well separated for IFI-EC fibers (see Methods for full explanation).

Discussion

We determined how the converter and relay domains affect cross-bridge rate constants, especially constants that have evolved to enable myosin to power superfast muscle contractions, by exchanging versions of these domains from the slower EMB isoform into the superfast IFI. We have previously shown that the converter and relay are critical for setting functional differences between muscle fiber types, particularly differences in power production of muscle (16). Our results demonstrate that the two domains influence cross-bridge mechanisms. Both the converter and relay are involved in slowing cross-bridge steps associated with 2πb, supporting the hypothesis that the relay and converter are part of the critical intermolecular communication pathway involved in lever-arm movement (5). However, that just the converter influences 2πc and only the relay affects work amplitude, suggests that these regions also independently influence different steps of the cross-bridge cycle.

Converter's influence on rate constants

Inserting the EMB converter into IFI produced an unusual myosin isoform. The IFI-EC isoform is not used by the fly in any muscle type examined to date (34), but it is very informative with regards to the functional importance and cross-bridge mechanisms influenced by the converter domain. Our first indication that IFI-EC was unusual was when we observed a decrease in actin motility and muscle power kinetics, to less than half of IFI control values (16), but the insertion also caused a 1.7-fold increase in actin-activated MgATPase rate (20); the mechanics and biochemistry appeared uncoupled. We hypothesized the decrease in actin motility and muscle fmax was caused by slowed detachment kinetics; perhaps the EMB converter indirectly decreased the MgADP release rate (16). The predominant theory at the time was that actin motility and fmax are most strongly influenced by MgADP release rate or an isomerization before MgADP release rate (35,36). However, transient kinetics studies of IFI-EC compared to IFI did not support MgADP release rate as being the cause (22). Instead, the opposite trend was observed, showing that the MgADP affinity for IFI-EC was half that of IFI. Similarly, MgATP-mediated detachment kinetics, k2KT, were ∼15% faster for IFI-EC compared to IFI (22).

Our observed 1.25-fold increases in IFI-EC 2πc and k2 when compared to IFI support the solution transient kinetic measurements that suggest MgADP release and subsequent detachment kinetics are not responsible for the decreased fmax of IFI-EC. We interpret 2πc to be set by the rates of work-absorbing steps of the cycle during strong binding states. These states incorporate the sequence of steps from MgADP release to myosin detachment from actin (Fig. 2). Increased k2 and decreased time in these strongly bound states would normally be expected to increase muscle kinetics, because these steps of the cross-bridge cycle are thought to have a strong influence on setting speeds for most muscle mechanical functions (35). Thus, IFI-EC myosin is unusual in that steps associated with detachment kinetics are not the primary influence on muscle kinetics during near isometric, oscillatory work production. A recent interpretation of 2πc is of its being equivalent to 1/tatt, the reciprocal of the time myosin is strongly attached to actin, which would predict a reduced attachment time for IFI-EC and thus support our interpretation of increased detachment rate (37).

Our current sinusoidal analysis data suggests that step(s) earlier than MgADP release are contributing to the slowing of IFI-EC muscle power generation kinetics, fmax. IFI-EC cross-bridge steps that set 2πb were dramatically decreased compared to IFI. Using the six-state cross-bridge model interpretation, IFI-EC k4 decreased 45% compared to IFI. In this model, the rate constant 2πb is primarily influenced by actin binding, Pi release, and work-producing isomerizations before, during, or after Pi release (Fig. 2) (24,25,32). Although any or all of these steps could be contributing to the decrease in 2πb, our data suggests that at least the rate of isomerization after Pi release has decreased. Based on previous modeling (25), the increase in 2πb with increasing [Pi] suggests that an isomerization between Pi release and MgADP release is rate-limiting for IFI-EC, while the flat response of IFI to [Pi] suggests Pi release is limiting for IFI. Thus, we propose that a myosin isomerization between Pi and MgADP release has been slowed by the EMB converter. That the converter can influence steps associated with Pi release has been demonstrated by two point mutations in Dictyostelium that disrupted the converters interface with the N-terminal subdomain. These mutations caused an increased in Pi release rate (38).

IFI-EC 2πc displayed a sharply decreasing response from 0 to 8 mM Pi, while the other two fiber type's responses were flat at these low Pi concentrations (Fig. 5 C). At higher Pi concentrations, there was a slight decreasing trend for IFI, IFI-9b, and IFI-EC as 2πc values for all three became similar at high Pi concentrations. We interpret these effects on 2πc being due to the very low MgATP affinity of all three myosins (Table 2) and IFI-EC's higher k2. The very low MgATP affinity results in a substantial competitive inhibition effect of Pi with MgATP for the A.M. state as we and others have shown previously (25,33,39). Because IFI-EC k2 is much higher than IFI and IFI-9b k2 values, the inhibition is immediately apparent for IFI-EC as its MgATP binding step is slower than its k2 rate over the range of MgATP concentrations used in this study. Thus, the Pi competition for A.M. (slowing MgATP binding) has an immediate, dramatic effect on IFI-EC 2πc, but it is not until higher concentrations of Pi are added that IFI and IFI-9b MgATP binding rates are slowed enough to impact 2πc. Performing the experiments at higher MgATP concentrations would have alleviated the competitive inhibition by Pi for the A.M. state (25). All three 2πc values would then have been relatively flat, but increasing MgATP higher than 13 mM would have increased the ionic strength to levels that would negatively impact actomyosin binding and force generation.

Relay's influence on rate constants

We found that the EMB relay decreased power generation amplitude as much as the converter (Fig. 4, A and B). However, while the EMB relay's effect on power occurred primarily because of a decrease in work production amplitude, a mechanical effect, the EMB converter had no effect on the amplitude of work production. The EMB relay also caused a slight decrease in muscle kinetics (fwmax decreased by 15%), but this was much less than the converter's 50% decrease in fwmax. The 15% decrease was caused by work-generating cross-bridge steps as the EMB relay decreased 2πb, but not 2πc compared to IFI. The value 2πb is set by work-producing steps of the cross-bridge cycle, mostly involving attachment to actin and Pi release (Fig. 2). We previously proposed that the relay exerts its influence by altering myosin's responsiveness to load (19). Because MgADP release and MgATP binding are sensitive to load (7,8), we had postulated that the relay is likely to influence these step(s) of the cycle (19). However, our current data shows no change in KATP, k2, or 2πc, suggesting the EMB relay does not change rates associated with MgATP binding and detachment kinetics.

Further evidence that the relay does not have as large an influence on muscle kinetics as the converter is that IFI-9b still appears to have the same rate-limiting step as IFI. The responses of IFI-9b 2πb and 2πc to [Pi] and [MgATP] all follow the same trends as IFI fibers. Particularly important is the flat response of IFI-9b 2πb to increasing [Pi]. Based on our modeling and the six-state cross-bridge model, this suggests that a step associated with Pi release is rate-limiting for IFI-9b kinetics, which is the same limiting step as IFI fibers (25). Thus, we suggest that the main reason for the 15% decrease in kinetics likely involves a slowing of this rate-limiting step.

Because the relay influences the amount of work produced, it must be changing myosin force production, inasmuch as the sinusoidal length changes were the same for all fibers tested. Duty cycle is not responsible for the observed decreased force generation because IFI-9b's decreased k4 suggests that the duty cycle has slightly decreased compared to IFI fibers, which would increase muscle force. Cross-bridge recruitment is unlikely to have been altered, leaving myosin stiffness or conformational changes associated with the power stroke as the most likely causes of decreased work production. The relay is postulated to undergo significant structural changes during the power stroke (5,6).

Recent transient kinetic data and associated structural modeling suggest the relay communicates with myosin's actin binding sites (40). Decreased actin affinity could be a mechanism by which the EMB relay decreased k4. Transient kinetic measurements also found that the EMB relay decreased actomyosin MgADP affinity and slowed MgATP-induced actin detachment kinetics (40). However, our data does not support these observations because IFI-9b 2πc was not altered compared to IFI. Perhaps this is again due to the relay responding differently under high and low loads (19). Our measurements were made under high oscillatory loads in a muscle while the transient kinetics measurements were made in solution with only actin and myosin present. In contrast, all of our results for IFI-EC agree with transient kinetic measurements of IFI-EC MgADP release rate and MgATP-associated detachment rate (22).

Combined relay and converter pathway

Our findings that the converter and relay domains both influence steps associated with force generation in the cross-bridge cycle, i.e., 2πb, support the proposal that proper interactions between the converter and relay are critical for the work-generating power stroke. Modeling the reversal of the power stroke suggests relay and converter domain interactions are essential for movement of the lever arm (5,41). Other studies have suggested that these two domains need to be linked throughout the cross-bridge cycle (42,43). However, they also can affect myosin function independently of each other. The relay influenced load sensitivity and work generation, while the converter increased the rates of cross-bridge steps associated with detachment. Continued use of the Drosophila system will further elucidate the structural mechanism by which these domains influence the cross-bridge cycle and vary muscle fiber type properties.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Brad Palmer, Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics at the University of Vermont, for the custom-written mechanics data acquisition software and helpful suggestions regarding data analysis. We thank Joan Braddock for assistance with initial IFI-EC data collection and analysis.

Financial support to D.M.S. was provided by National Institutes of Health grant No. AR055611 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and American Heart Association Scientist Development grant No. 0635058N.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Rayment I., Holden H.M., Milligan R.A. Structure of the actin-myosin complex and its implications for muscle contraction. Science. 1993;261:58–65. doi: 10.1126/science.8316858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dominguez R., Freyzon Y., Cohen C. Crystal structure of a vertebrate smooth muscle myosin motor domain and its complex with the essential light chain: visualization of the pre-power stroke state. Cell. 1998;94:559–571. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81598-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warshaw D.M., Guilford W.H., Trybus K.M. The light chain binding domain of expressed smooth muscle heavy meromyosin acts as a mechanical lever. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:37167–37172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes K.C. The swinging lever-arm hypothesis of muscle contraction. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:R112–R118. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer S., Windshügel B., Smith J.C. Structural mechanism of the recovery stroke in the myosin molecular motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6873–6878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408784102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes K.C., Schröder R.R., Houdusse A. The structure of the rigor complex and its implications for the power stroke. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004;359:1819–1828. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kad N.M., Patlak J.B., Warshaw D.M. Mutation of a conserved glycine in the SH1-SH2 helix affects the load-dependent kinetics of myosin. Biophys. J. 2007;92:1623–1631. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veigel C., Molloy J.E., Kendrick-Jones J. Load-dependent kinetics of force production by smooth muscle myosin measured with optical tweezers. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:980–986. doi: 10.1038/ncb1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith D.A., Geeves M.A. Strain-dependent cross-bridge cycle for muscle. Biophys. J. 1995;69:524–537. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79926-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geeves M.A., Fedorov R., Manstein D.J. Molecular mechanism of actomyosin-based motility. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:1462–1477. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5015-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geeves M.A., Holmes K.C. The molecular mechanism of muscle contraction. Adv. Protein Chem. 2005;71:161–193. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)71005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Köhler J., Winkler G., Kraft T. Mutation of the myosin converter domain alters cross-bridge elasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3557–3562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062415899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seebohm B., Matinmehr F., Kraft T. Cardiomyopathy mutations reveal variable region of myosin converter as major element of cross-bridge compliance. Biophys. J. 2009;97:806–824. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George E.L., Ober M.B., Emerson C.P., Jr. Functional domains of the Drosophila melanogaster muscle myosin heavy-chain gene are encoded by alternatively spliced exons. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989;9:2957–2974. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.2957. (published erratum appears in Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989 Sep;9(9):4118) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernstein S.I., Mogami K., Emerson C.P., Jr. Drosophila muscle myosin heavy chain encoded by a single gene in a cluster of muscle mutations. Nature. 1983;302:393–397. doi: 10.1038/302393a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swank D.M., Knowles A.F., Bernstein S.I. The myosin converter domain modulates muscle performance. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:312–316. doi: 10.1038/ncb776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swank D.M., Braddock J., Maughan D.W. An alternative domain near the ATP binding pocket of Drosophila myosin affects muscle fiber kinetics. Biophys. J. 2006;90:2427–2435. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.075184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swank D.M., Kronert W.A., Maughan D.W. Alternative N-terminal regions of Drosophila myosin heavy chain tune muscle kinetics for optimal power output. Biophys. J. 2004;87:1805–1814. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.032078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang C., Ramanath S., Swank D.M. Alternative versions of the myosin relay domain differentially respond to load to influence Drosophila muscle kinetics. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5228–5237. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Littlefield K.P., Swank D.M., Bernstein S.I. The converter domain modulates kinetic properties of Drosophila myosin. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C1031–C1038. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00474.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maughan D.W., Vigoreaux J.O. An integrated view of insect flight muscle: genes, motor molecules, and motion. News Physiol. Sci. 1999;14:87–92. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1999.14.3.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller B.M., Nyitrai M., Geeves M.A. Kinetic analysis of Drosophila muscle myosin isoforms suggests a novel mode of mechanochemical coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:50293–50300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kronert W.A., Dambacher C.M., Bernstein S.I. Alternative relay domains of Drosophila melanogaster myosin differentially affect ATPase activity, in vitro motility, myofibril structure and muscle function. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;379:443–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawai M., Brandt P.W. Sinusoidal analysis: a high resolution method for correlating biochemical reactions with physiological processes in activated skeletal muscles of rabbit, frog and crayfish. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1980;1:279–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00711932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swank D.M., Vishnudas V.K., Maughan D.W. An exceptionally fast actomyosin reaction powers insect flight muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17543–17547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604972103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawai M., Zhao Y., Halvorson H.R. Elementary steps of contraction probed by sinusoidal analysis technique in rabbit psoas fibers. In: Sugi H., Pollack G.J., editors. Mechanisms of myofilament sliding in muscle contraction. Plenum Press; New York: 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyitrai M., Rossi R., Geeves M.A. What limits the velocity of fast-skeletal muscle contraction in mammals? J. Mol. Biol. 2006;355:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swank D.M., Wells L., Bernstein S.I. Determining structure/function relationships for sarcomeric myosin heavy chain by genetic and transgenic manipulation of Drosophila. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2000;50:430–442. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20000915)50:6<430::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Godt R.E., Lindley B.D. Influence of temperature upon contractile activation and isometric force production in mechanically skinned muscle fibers of the frog. J. Gen. Physiol. 1982;80:279–297. doi: 10.1085/jgp.80.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickinson M.H., Hyatt C.J., Maughan D.W. Phosphorylation-dependent power output of transgenic flies: an integrated study. Biophys. J. 1997;73:3122–3134. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78338-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulieri L.A., Barnes W., Maughan D.W. Alterations of myocardial dynamic stiffness implicating abnormal crossbridge function in human mitral regurgitation heart failure. Circ. Res. 2002;90:66–72. doi: 10.1161/hh0102.103221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawai M. Correlation between exponential processes and cross-bridge kinetics. In: Twarog B.M., Levine R.J.C., Dewey M.M., editors. Basic Biology of Muscles: A Comparative Approach. Raven Press; New York: 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galler S., Wang B.G., Kawai M. Elementary steps of the cross-bridge cycle in fast-twitch fiber types from rabbit skeletal muscles. Biophys. J. 2005;89:3248–3260. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.056614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang S., Bernstein S.I. Spatially and temporally regulated expression of myosin heavy chain alternative exons during Drosophila embryogenesis. Mech. Dev. 2001;101:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00549-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss S., Rossi R., Geeves M.A. Differing ADP release rates from myosin heavy chain isoforms define the shortening velocity of skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:45902–45908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujita H., Sasaki D., Kawai M. Elementary steps of the cross-bridge cycle in bovine myocardium with and without regulatory proteins. Biophys. J. 2002;82:915–928. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75453-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer B.M., Suzuki T., Maughan D.W. Two-state model of acto-myosin attachment-detachment predicts C-process of sinusoidal analysis. Biophys. J. 2007;93:760–769. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Málnási-Csizmadia A., Tóth J., Kovács M. Selective perturbation of the myosin recovery stroke by point mutations at the base of the lever arm affects ATP hydrolysis and phosphate release. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:17658–17664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pate E., Cooke R. Addition of phosphate to active muscle fibers probes actomyosin states within the powerstroke. Pflugers Arch. 1989;414:73–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00585629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bloemink M.J., Dambacher C.M., Bernstein S.I. Alternative exon 9-encoded relay domains affect more than one communication pathway in the Drosophila myosin head. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;389:707–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mesentean S., Koppole S., Fischer S. The principal motions involved in the coupling mechanism of the recovery stroke of the myosin motor. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;367:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shih W.M., Spudich J.A. The myosin relay helix to converter interface remains intact throughout the actomyosin ATPase cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:19491–19494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sasaki N., Ohkura R., Sutoh K. Dictyostelium myosin II mutations that uncouple the converter swing and ATP hydrolysis cycle. Biochemistry. 2003;42:90–95. doi: 10.1021/bi026051l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernstein S.I., Milligan R.A. Fine tuning a molecular motor: the location of alternative domains in the Drosophila myosin head. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;271:1–6. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.