Abstract

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) provide an unprecedented opportunity for modeling of human diseases in vitro, as well as for developing novel approaches for regenerative therapy based on immunologically compatible cells. In this study we employed an OP9 differentiation system to characterize the hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation potential of seven human iPSC lines obtained from human fetal, neonatal, and adult fibroblasts through reprogramming with POU5F1, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 and compared it with the differentiation potential of five human embryonic stem cell lines (hESC, H1, H7, H9, H13, and H14). Similar to hESCs, all iPSCs generated CD34+CD43+ hematopoietic progenitors and CD31+CD43− endothelial cells in coculture with OP9. When cultured in semisolid media in the presence of hematopoietic growth factors, iPSC-derived primitive blood cells formed all types of hematopoietic colonies, including GEMM-CFCs. hiPSC-derived CD43+ cells could be separated into the following phenotypically defined subsets of primitive hematopoietic cells: CD43+CD235a+CD41a+/− (erythro-megakaryopoietic), lin−CD34+CD43+CD45− (multi-potent) and lin−CD34+CD43+CD45+ (myeloid-skewed) cells. While we observed some variations in the efficiency of hematopoietic differentiation between different hiPSCs, the pattern of differentiation was very similar in all seven tested lines obtained through reprogramming of human fetal, neonatal or adult fibroblasts with three or four genes. Although several issues remain to be resolved before iPSC-derived blood cells can be administered to humans for therapeutic purposes, patient-specific iPSCs can already be used for characterization of mechanisms of blood diseases and for identification of molecules that can correct affected genetic networks.

Keywords: induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells, hematopoietic cells, endothelial cells

Direct reprogramming of somatic cells allows the generation of patient-specific pluripotent cell lines and provides an unprecedented opportunity for modeling of human diseases in vitro, as well as for development of novel approaches for regenerative therapy based on immunologically compatible cells. It has been shown that four transcription factors (Pou5f1, Sox2, Myc, and Klf4) are sufficient to reprogram mouse fibroblasts [1–4] and other terminally differentiated cells [5,6]. Recently pluripotent cell lines have been obtained through reprogramming of human fibroblasts [7–9]. Human induced pluripotent cells (hiPSC) behave similar to human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), i.e. capable of self-renewal and large-scale expansion and differentiation toward all three germ layers, including cardiac, neural and erythroid cells [7–9]. However, the differentiation potential of iPSCs is still uncharacterized and it is not yet clear whether iPSCs undergo a series of cellular changes similar to hESCs following differentiation to specific lineages. We have shown that hESC differentiation in coculture with mouse bone marrow stromal cell line OP9 proceeds through formation of population of CD34+ cells that include CD34+CD43+ hematopoietic cells, CD34+CD31+KDR+CD43− endothelial cells, and CD34+CD31+KDR− CD43- cells of mesenchymal lineage. The first-appearing CD43+ hematopoietic cells generated from hESCs express CD235a, CD41a, and possess restricted erythro-megakaryocytic potential. The earliest hematopoietic cells with broad lymphomyeloid differentiation potential to appear from hESCs differentiating in vitro are identified as lin−CD34+CD43+CD45− cells. Later, lin−CD34+CD43+CD45+ myeloid-skewed cells emerge [10]. In the present study we employed the OP9 differentiation system to characterize the hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation patterns of seven hiPSC lines obtained from human fetal, neonatal and adult fibroblasts through reprogramming with POU5F1, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 [7]. While we observed some variations in efficiency of hematopoietic differentiation between different hiPSCs, the pattern of differentiation was very similar in all tested hiPSC and hESC lines. This data provides additional evidence that hiPSCs resemble hESCs.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

H1 (NIH code WA01), H7 (WA07), H9 (WA09), H13 (WA13), and H14 (WA14) hES cells (passages 27–45; WiCell Research Institute, Madison, WI) were maintained as undifferentiated cells in cocultures with mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) [11]. iPS(IMR90)-4 and iPS(foreskin)-1 hiPSC lines were obtained by reprogramming IMR90 fetal and newborn foreskin fibroblasts with POU5F1, SOX2, and NANOG; iPS(IMR90)-1, iPS(foreskin)-2, were obtained by reprogramming of fetal and newborn foreskin fibroblasts (ATCC) with POU5F1, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 as described [7]. iPS(SK46)-M3-6, iPS(SK46)-M4-8, and iPS(SK46)-M4-10 hiPSC lines were obtained by reprogramming adult skin fibroblasts with POU5F1, SOX2, and NANOG (M3-6) or POU5F1, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 (M4-8 and M4-10). Characterization of SK-46 derived cell lines is provided in STable 1 and SFig.1. The hiPSC lines (Foreskin: passages 21–45; IMR90: passages 21–45; SK46: passages 9–33) were maintained in an undifferentiated state in coculture with MEFs essentially in the same conditions as hESCs [11], but with higher concentration of bFGF (100 ng/ml; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) [7]. A mouse bone marrow stromal cell line OP9 was obtained from Dr. Toru Nakano (Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University, Japan). This cell line was maintained on gelatinized 10 cm dishes (BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA) in the OP9 growth medium consisting of α-MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 20% defined FBS (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT) [12].

Differentiation of hiPSCs and hESCs in coculture with OP9

Hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation of hiPSCs and hESCs was induced by transferring the cells onto OP9 feeders, as we previously described in details [12,13]. Briefly, undifferentiated hESC/iPSCs were harvested by treatment with 1 mg/ml collagenase IV (Invitrogen) and added to OP9 cultures at an approximate density of 1.2×106/20 ml per 10 cm dish in α–MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Logan, Utah) and 100 µM monothioglycerol (MTG; (MTG; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The cocultures of OP9 with pluripotent cells were incubated for 8 days, with a half medium change on days 4 and 6 without added cytokines. Differentiated hESCs/hiPSCs were harvested by treatment with collagenase IV (Invitrogen; 1 mg/ml in α-MEM) for 20 min at 37°C, followed by treatment with 0.05% Trypsin-0.5 mM EDTA (Invitrogen) for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were washed twice in PBS-5%FBS and filtered through a 70 µm cell strainer (BD) and used for further analysis.

Assessment of hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation by FACS analysis

Cells were prepared in PBS-2%FBS containing 0.05% sodium azide, 1mM EDTA and 1% mouse serum (Sigma), and labeled with multicolor monoclonal antibody combinations. Samples were analyzed using FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD) and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). 7-aminoactinomycin (7AAD) staining solution (Via-Probe, BD) is used for dead cell exclusion. Human cells in OP9 coculture were identified using TRA-1-85-APC monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) which detects the OK, a blood group antigen expressed by virtually all human cells [14]. The percentage of hematopoietic (CD43+) and endothelial (CD31+CD43−) cells is determined within the population of viable human cells (7AAD−TRA-1-85+). Absolute numbers of each studied cell population were calculated based on the total number of cells harvested from one 10 cm dish in OP9 coculture, the percentage of total viable human cells, and the percentage of the cell population of interest [12]. The fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies used for identification and characterization of cell subsets included CD11b-FITC, CD13-PE, myeloperoxidase (MPO)-FITC, CD105-PE (CALTAG-Invitrogen); CD49d-PE, CD54-PE (BioLegend, San Diego, CA); KDR-PE, CD117-PE (R&D, Minneapolis, MN); CD15-FITC, CD31-APC, (Miltenyi biotec, Bergisch Gladbch, Germany); CD2-FITC, CD3-FITC, CD7-PE, CD16-FITC, CD19-FITC, CD31-PE, CD34-PE, APC, CD41a-FITC, PE, APC, CD43-FITC, APC (Clone 1G10), CD45-FITC, PE, APC, CD66b-FITC, CD90-APC, CD133-PE, CD146-PE, CD235a-FITC, PE, APC, and CXCR4-PE. For indirect staining unconjugated SSEA-3, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), vWF (von Willebrand factor; BD Biosciences) and goat anti-mouse IgM-FITC (BD Pharmingen), goat anti-mouse-FITC (BD Pharmingen) or -PE (CALTAG-Invitrogen) as secondary antibody, were used. FIX&PERM cell permeabilization reagents (CALTAG-Invitrogen) were utilized for intracellular staining for vWF.

Cell sorting

CD34+ cells were isolated using magnet-activated cell sorting (MACS) with CD34 Multisort direct microbeads (Milteneyi Biotech). After labeling with CD43 and CD31 monoclonal antibodies CD34+CD43+, CD34+CD31+CD43− and CD34+CD31−CD43− subsets were purified using FACSVantage (Becton Dickenson) cell sorter. For isolation of hematopoietic cell subsets, CD43+ cells were selected by MACS using CD43-FITC antibodies/anti-FITC microbeads (Milteneyi Biotech). Separated CD43+ cells were labeled with CD235a, CD41a and CD45 monoclonal antibodies, and subsequently subjected to a FACS sorting to isolate three subsets of hematopoietic progenitors: CD235a/CD41a+CD43+CD45−, CD235a/CD41a−CD43+CD45− and CD235a/CD41a−CD43+CD45+ cells. In some experiments, CD31+CD43− cells were isolated from CD43− cell fraction by positive selection of cells labeled with CD31-PE antibodies and anti-PE microbeads (Milteneyi Biotech) [12].

Clonogenic progenitor cell assay

Hematopoietic clonogenic assays were performed in 35mm low-adherent plastic dishes (greiner Bio-one, Monroe, NC) using 1 ml/dish of MethoCult GF+ H4435 semisolid medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) containing SCF, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-3, IL-6 and EPO according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell plating densities for CFC assays were optimized according to cell subsets tested [10]. Colonies were scored after 14–21 days of incubation based on the morphological criteria as erythroid (E-CFC), granulocyte/erythrocyte/macrophage/megakaryocyte (GEMM-CFC), granulocyte/macrophage (GM-CFC), granulocyte (G-CFC) and macrophage (M-CFC).

Endothelial cell culture, immunofluorescent staining, and vascular tube formation assay

For endothelial cultures, cells were plated onto fibronectin (GIBCO-Invitrogen)-coated plastic dishes (BD Falcon) at 2×104 cells/cm2 in endothelial serum-free medium (ESFM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; Invitrogen) and 1/100 dilution of endothelial cell growth factor (acidic FGF+heparin; Sigma). Cells were cultured until confluence for 5–7 days, and detached by HyQTase (HyClone) for analysis. For immunofluorescent staining, endothelial cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) and blocked with Image-iT-FX signal enhancer (Molecular Probes-Invitrogen). Samples were stained with indicated VE-cadherin antibodies, and examined using Olympus IX71 Inverted Research Microscope (Leeds Precision Instruments, Minneapolis, MN), equipped with Retiga 2000R FireWire digital camera (QImaging, Surray BC, Canada). For vascular tube formation, growth factor reduced Matrigel (BD Falcon) was added into a 24-well plate (0.5 ml/well) and allowed to solidify for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells prepared in ESFM with 40 ng/ml vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; Peprotech) were plated onto gel matrix (5×104 cells/well in 0.5 ml medium) and incubated 24 hours at 37°C.

Results and Discussion

Human iPSCs differentiate into CD43+ hematopoietic and CD31+CD43− endothelial cells

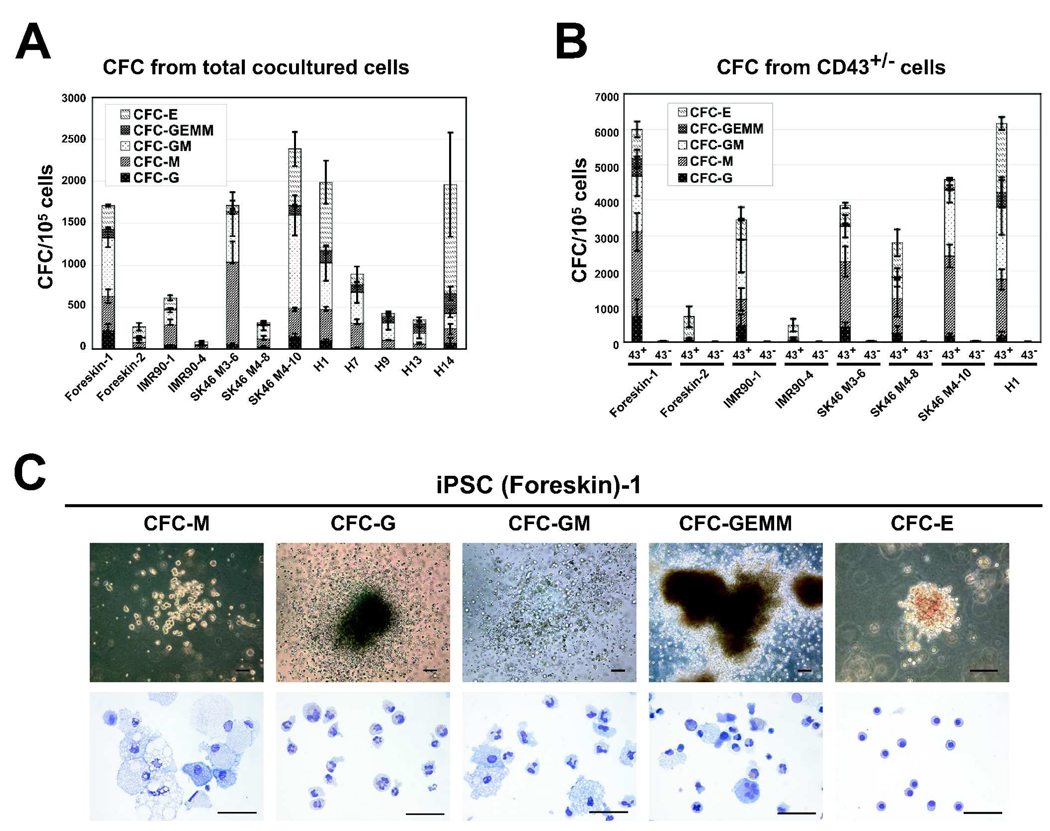

Previously we demonstrated that human H1 and H9 hESC lines in coculture with OP9 undergo a series of changes with formation of CD34+ cell population that include CD34+CD43+ hematopoietic cells, CD34+CD31+CD43− endothelial cells and CD34+CD31−CD43− cells of mesenchymal lineage (Fig. 1) [10]. Other tested hESC lines (H7, H13, and H14) were capable of differentiation toward endothelial and hematopoietic CD34+ cells as well; however, the most robust hematoendothelial differentiation was observed from H1 and H14 cells (Table 1, Fig. 2). To characterize the differentiation potential of seven different hiPSC lines, we cocultured these cells with OP9 feeders for 8 days. As shown in Fig. 1 and 2, hiPSCs in these conditions generated all types of colony forming cells (CFCs) as well as CD34+ cells that can be separated into distinct subsets based on differential expression of CD43 and CD31 similar to hESC progeny. The efficiency of differentiation was variable among seven tested hiPSC lines, with iPS(foreskin)-1 and iPS(SK46)-M4-10 cells showing the highest number of CD43+ cells and CFCs, and iPS(IMR90)-4 the lowest number of cells with hematopoietic potential (Table 1). In this work, we used iPSCs obtained through reprogramming somatic fibroblasts at different stages of ontogeny (fetal iPS(IMR90), neonatal iPS(foreskin), and adult iPS(SK46)) with a set of three (POU5F1, SOX2, NANOG; iPS(IMR90)-4, iPS(foreskin)-1, and iPS(SK46)-M-3-6) or four (POU5F1, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28; iPS(IMR90)-1, iPS(foreskin)-2, and iPS(SK46)-M-4-8, and M4-10) reprogramming factors. However, no correlation between the origin of fibroblasts or number of reprogramming factors used and the efficiency of hematopoietic differentiation was observed. For example, iPS(SK46)-M-4-8 and M4-10 cell lines were derived from the same donor using the same four factors, and nevertheless significant differences in hematopoietic differentiation potential was observed between these two cell lines. It is possible that these differences could be related to distinct viral integration sites in these clones that can influence activation of the hematopoietic differentiation program. In our prior [7] and current work we examined the differentiation potential of 3–4 different clones obtained from the same starting material (fetal, newborn, or adult fibroblasts) and were able to generate at least one clone with good differentiation potential toward all three germ cell layers including blood and endothelial cells. Based on this experience we could estimate that generation of 3–4 iPSC clones from single donor would be sufficient to ensure that at least one clone could efficiently differentiate toward tissue of interest.

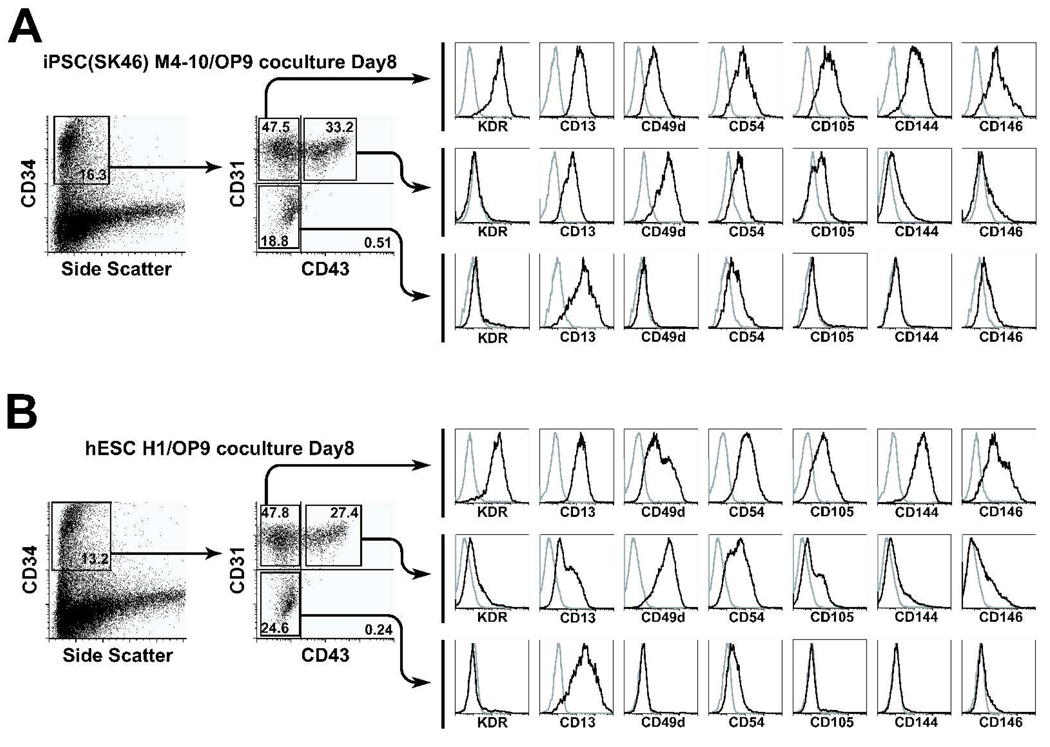

Figure 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD34+ and CD43+ subsets generated in OP9 coculture from (A) hiPSCs (IPS(SK46)-M4-10) and (B) hESCs (H1). There are striking similarities between the subsets of hematopoietic cells developed from these two types of pluripotent cells. Representative analysis of 5 independent experiments is shown.

Table 1.

Hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation of human induced pluripotent and embryonic stem cells*

| Human induced pluripotent stem cells | Human embryonic stem cells | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreskin-1 | Foreskin-2 | IMR90-1 | IMR90-4 | SK46 M3-6 | SK46 M4-8 | SK46 M4-10 | H1 | H7 | H9 | H13 | H14 | |

| Human cells (TRA-1-85+7-AAD−), ×105 | 86.8 ± 19.3 | 68.5 ± 8.8 | 78.5 ± 6.7 | 84.3 ± 13.7 | 97.5 ± 13.1 | 60.2 ± 8.2 | 96.6 ± 9.6 | 130.4 ± 10.2 | 101.7 ± 16.3 | 121.3 ± 19.8 | 106.5 ± 18.3 | 86.0 ± 11.4 |

| CD31+CD43− Endothelial cells, ×105 (%within gated human cells) |

4.0 ± 0.9 (5.2 ± 0.3) |

4.1 ± 0.5 (6.0 ± 0.2) |

2.7 ± 0.3 (3.4 ± 0.3) |

2.4 ± 0.5 (2.8 ± 0.4) |

4.5 ± 0.5 (4.7 ± 0.4) |

2.1 ± 0.5 (3.5 ± 1.1) |

0.37 ± 0.6 (4.2 ± 0.2) |

7.2 ± 0.6 (5.3 ± 0.4) |

5.3 ± 0.9 (5.5 ± 0.9) |

5.6 ± 1.6 (4.3 ± 1.5) |

4.6 ± 0.6 (4.6 ± 0.6) |

4.2 ± 0.9 (4.7 ± 0.5) |

| CD43+ Hematopoietic cells, ×105 (%within gated human cells) |

11.8 ± 3.0 (16.1 ± 2.7) |

3.8 ± 1.1 (5.7 ± 1.7) |

6.7 ± 1.4 (8.7 ± 1.5) |

1.5 ± 0.1 (1.9 ± 0.3) |

4.2 ± 0.7 (4.2 ± 0.2) |

1.8 ± 0.7 (3.1 ± 1.4) |

9.4 ± 1.6 (11.5 ± 1.9) |

12.2 ± 3.0 (9.6 ± 1.9) |

9.7 ± 3.0 (9.6 ± 2.5) |

6.3 ± 1.7 (5.1 ± 2.2) |

3.0 ± 0.9 (3.1 ± 1.0) |

16.8 ± 5.2 (18.1 ± 4.1) |

| CD41a+CD235a+CD45− cells, ×105 (% within gated CD43+cells) |

9.9 ± 2.7 (69.5 ± 6.1) |

3.2 ± 1.0 (84.7 ± 2.0) |

5.5 ± 1.7 (76.0 ± 5.0) |

1.3 ± 0.1 (81.7 ± 0.8) |

2.8 ± 0.4 (67.4 ± 3.8) |

1.3 ± 0.5 (73.2 ± 4.9) |

6.4 ± 1.4 (66.9 ± 2.3) |

9.72 ± 3.4 (72.4 ± 4.9) |

8.7 ± 2.9 (83.4 ± 2.5) |

4.8 ± 1.2 (77.4±7.1) |

2.3 ± 0.6 (79.4 ± 3.5) |

14.9 ± 5.9 (87.0 ± 3.6) |

| CD41a−CD235a−CD45− cells, ×105 (%within gated CD43+cells) |

1.4 ± 0.4 (9.8 ± 0.9) |

0.2 ± 0.0 (6.9 ± 0.8) |

0.4 ± 0.1 (5.8 ± 0.5) |

< 0.1 (5.6 ± 1.0) |

0.8 ± 0.2 (17.6 ± 2.0) |

0.1 ± 0.0 (5.7 ± 0.5) |

1.0 ± 0.2 (11.0 ± 0.7) |

1.2 ± 0.1 (11.7 ± 2.8) |

0.6 ± 0.2 (5.5 ± 0.5) |

0.8 ± 0.3 (10.4± 3.3) |

0.2 ± 0.1 (6.2 ± 3.5) |

0.8 ± 0.3 (4.9 ± 0.7) |

| CD41a−CD235a−CD45+ cells, ×105 (%within gated CD43+cells) |

1.9 ± 0.7 (15.9 ± 5.7) |

0.1 ± 0.0 (2.9 ± 0.5) |

0.7 ± 0.3 (10.8 ± 4.2) |

< 0.1 (1.3 ± 0.2) |

0.4 ± 0.1 (9.9 ± 1.1) |

0.3 ± 0.1 (11.9 ± 3.5) |

1.4 ± 0.4 (14.9 ± 2.1) |

1.5 ± 0.4 (11.8 ± 3.3) |

0.6 ± 0.3 (4.3 ± 1.7) |

0.8 ± 0.3 (8.3 ± 1.0) |

0.2 ± 0.1 (6.0 ± 2.6) |

0.9 ± 0.6 (4.2 ± 2.3) |

The absolute number of cells generated from one 10 cm dish of hESC/OP9 coculture is shown. The percentage of cells within indicated cell population is displayed in parentheses. Results are mean±SE of 3 to 5 independent experiments.

Figure 2.

CFC potential of hESC and hiPSC lines. (A) CFC potential of total cells obtained at day 8 of OP9 coculture. (B) CFC potential of CD43+ and CD43− MACS sorted cells. Results are mean±SE of 3–5 independent experiments. (C) Morphology (upper row, bars are 100 µm) and Wright-stained cytospins (lower row, bars are 50 µm) of CFCs obtained from (SK46)-M4-10 hiPSCs.

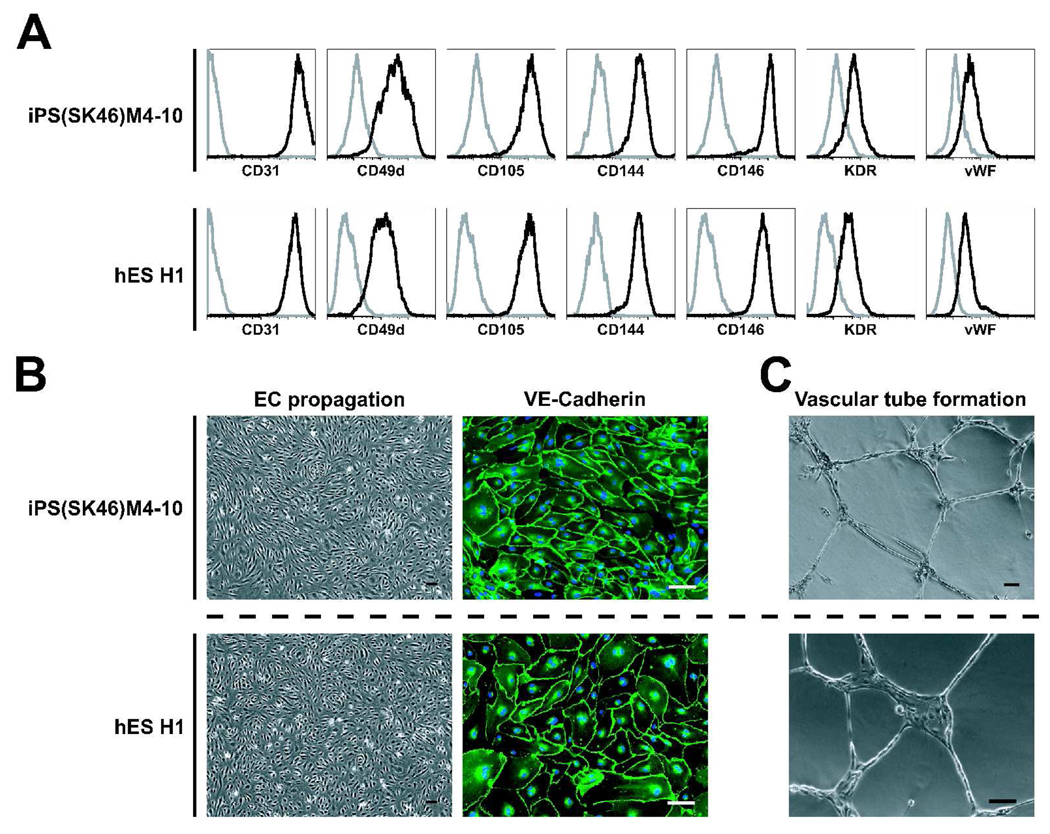

To determine whether phenotypic differences within the hiPSC-derived CD34+ subpopulation reflect a distinct differentiation potential of these subsets, we isolated CD34+CD31+CD43−, CD34+CD43+ and CD34+CD31−CD43− cells generated following their differentiation in OP9 coculture. As expected, CD34+CD31+CD43− cells obtained from all hiPSC lines expressed molecules present on endothelial cells (Fig.1) and readily formed a monolayer when placed in endothelial conditions (Fig.3). Expanded endothelial cells expressed VE-cadherin (CD144), vWF, KDR, CD31, CD49d, and CD105 and formed capillary-like structures when seeded in Matrigel in the presence of VEGF (Fig.3). At the same time, no viable cells were detected when CD43+ cells were cultured in endothelial conditions for 7–9 days, indicating a lack of endothelial potential within this population. CD34+CD31−CD43− cells displayed the phenotypic features of mesenchymal lineage cells (Fig.1) and were lacking of hematopoietic and endothelial potential (not shown).

Figure 3.

Phenotype and function of hiPSC- and hESC-derived endothelial cells. Isolated CD31+CD43− cells were cultured for 7 days in endothelial conditions. (A) Expression of markers of endothelial cells by flow cytometry. (B) Typical morphology of endothelial cell monolayer formed by CD31+CD43− cells (left panels) and immunofluorescent staining of monolayer for VE-cadherin (right panel); cell nuclei visualized by DAPI staining. (C) Vascular tube formation by expanded endothelial cells. All bars are 100µm. Representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown.

The standard CFC assay was performed to evaluate the hematopoietic potential of hiPSC-derived CD43+ and CD31+CD43− cells. Similar to hESCs, hematopoietic activity generated from all studied hiPSCs was essentially confined to the CD43+ cell population (Fig 2B).

To find out whether reprogramming viruses expressed or were silent in differentiated cells, we analyzed the expression of total and endogenous POU5F1, SOX2, and NANOG genes in undifferentiated H1 hESCs and three selected hiPSC lines, as well CD43+ cells derived from corresponding pluripotent stem cells. As shown in SFig.2A, significant downregulation of pluripotency genes was observed following hematopoietic differentiation of both hESCs and hiPSCs. Interestingly, both endogenous and retrovirally introduced pluripotency genes were silenced in hiPSC-derived CD43+ cells, although exogenous NANOG expression was still detectable in these cells. However, no expression of markers of undifferentiated hESCs (SSEA-3, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81) was detected in hESC- as well as hiPSC-derived hematopoietic (CD43+) and endothelial cells (CD31+CD43−) cells by flow cytometry (SFig.2B).

Cytogenetic analysis demonstrated that hiPSCs and CD43+ cells derived from them maintained normal karyotype (SFig.3). In addition, short tandem repeat analysis of CFCs generated from iPS(IMR90)-1 cells was performed to confirm that blood cells were in fact derived from reprogrammed IMR90 cells, and not from potentially contaminating hESCs (STable 2).

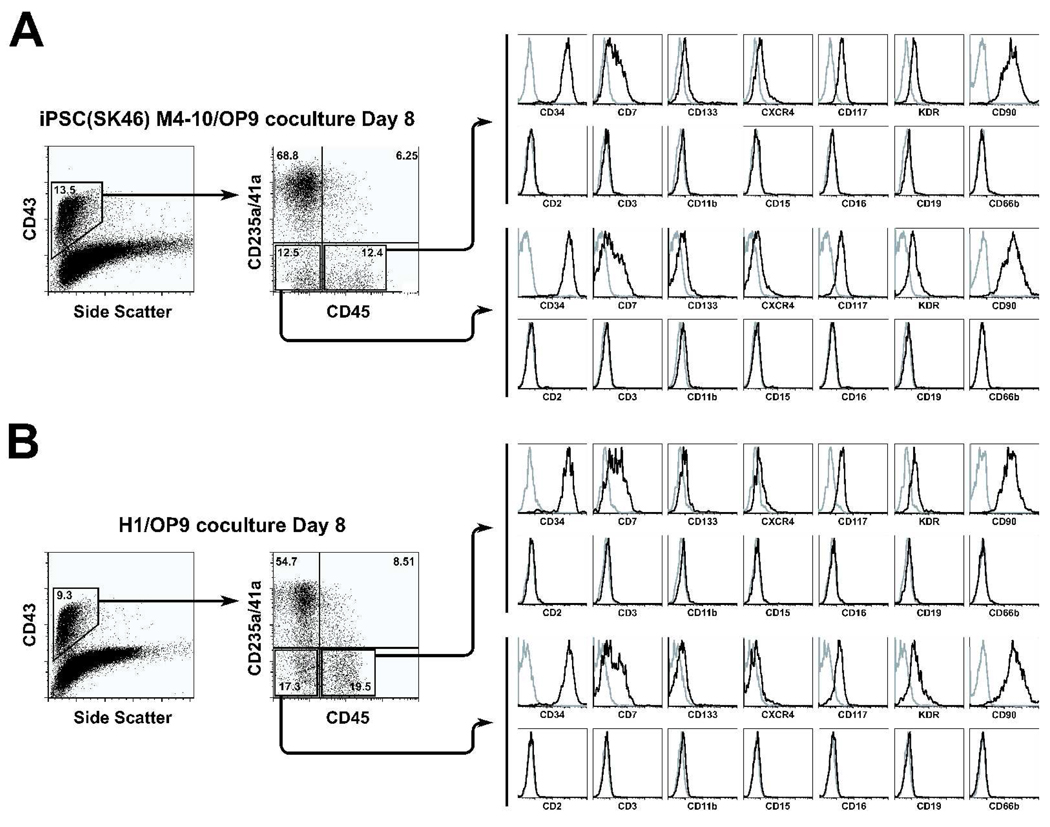

The hiPSCs generate distinct subsets of the primitive hematopoietic cells in OP9 coculture

Based on differential expression of CD235a/CD41a and CD45, three major populations of CD43+ hematopoietic cells can be discriminated in OP9 coculture with pluripotent cells: CD235a/CD41a+, CD235a/CD41a−CD45− and CD235a/CD41a−CD45+. Because CD235/CD41a− cells generated during 8 day of coculture with OP9 were essentially lacking other lineage markers and expressed CD34 (Fig.4), we designated these two subsets as lin−CD34+CD43+CD45− and lin−CD34+CD43+CD45+ cells.

Figure 4.

Flow cytometric analysis of phenotype of hiPSC- (A) and hESC-derived (B) CD34+CD43+CD45− and CD34+CD43+CD45+ primitive hematopoietic cells. Plots show isotype control (open gray) and specific antibody (open black) histograms. The representative experiment of 3–5 independent experiments is shown.

The proportion and absolute number of erythro-megakaryocytic progenitors and pluripotent cells were variable between different hiPSC and hESC lines. H1, H9, iPS(foreskin)-1, iPS(SK46)-M3-6, and iPS(SK46)-M4-10 cells produced the highest number of lin−CD34+CD43+CD45+/− multipotent cells, while H14, iPS(foreskin)-2, iPS(IMR90)-1 and iPS(IMR90)-4 generated the highest number of CD43+CD235a/CD41a+ cells (Table 1).

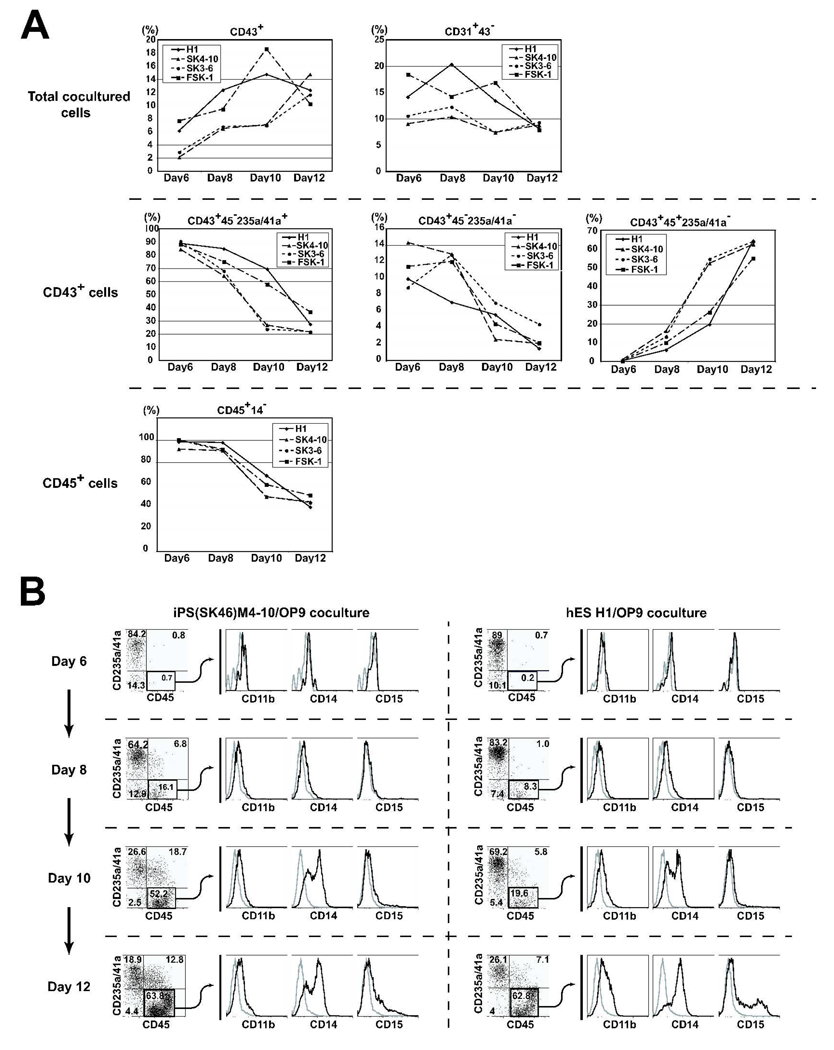

In present work we examined the differentiation potential of pluripotent stem cells on day 8 of OP9 coculture because we found that on days 8–9 of differentiation the highest numbers of endothelial cells, the most primitive hematopoietic cells (CD43+CD235a/CD41a+, lin−CD34+CD43+CD45−, lin−CD34+CD43+CD45+) and CFCs are generated from hESCs [10,13]. To address the question of whether observed differences in the differentiation potential of hESCs and iPSCs could be related to a distinct kinetic of hematopoietic development, we evaluated indicated subsets of hematopoietic cells over a 6–12 days of differentiation in OP9 coculture. Similar to prior findings with hESCs, we found that endothelial cells and all types of hematopoietic cells were detected on day 6 of differentiation in OP9 cocultures with all three studied hiPSCs. However the percentage of CD31+CD43− endothelial cells, CD43+CD235a/CD41a+ eryhro-megakaryocytic progenitors, and lin−CD34+CD43+CD45− multipotent cells substantially decreased after 10 days of differentiation (Fig.5). While the number of CD43+CD45+CD235a/CD41a− cells dramatically increased over a longer time-course, these cells acquired expression of CD11b, CD14 and CD15, indicative of their progressive differentiation/maturation toward myelomonocytic lineage. In fact, the percentage of lin-CD45+ (CD43+CD45+CD235a/CD41a−CD14−) primitive hematopoietic cells substantially decreased if hiPSCs were cultured with OP9 for more than 10 days (Fig.5). These data provide further evidence of similarity in patterns of hematopoietic differentiation of hESCs and hiPSCs.

Figure 5.

Kinetic analysis of hematopoietic and endothelial development from pluripotent stem cells in OP9 coculture (days 6–12 of differentiation). (A) Percentages of CD43+ hematopoietic and CD31+CD43− endothelial cells within live human (TRA-1-85+7-AAD−) cells (upper row), CD235a/CD41a+, CD235a/CD41a−CD45− and CD235a/CD41a−CD45+ within gated CD43+ cells (middle row) and CD14− cells within gated CD45+ cells (lower row) are shown. (B) Expression of myeloid lineage markers on hiPSC- and hESC-derived CD45+ cells following differentiation in OP9 cocluture.

Direct reprogramming of somatic cells to the pluripotent state paves the way to the future of patient-specific stem cell based therapies. However, many hurdles remain to be overcome before hiPSC-based therapy can be moved to the clinic. The reprogramming of cells without using retroviruses would be the most important milestone in this direction. Recent success with the generation of mouse iPSCs without viral integration strongly suggests that reprogramming of cells without insertional mutagenesis could be accomplished in humans, as well [15,16]. In addition, the differentiation potential of iPSCs has to be evaluated, and methods for large scale production of cells of specific lineage from iPSCs in defined xenogenic-free conditions must be developed. The major stages of hematopoietic development from hESCs were identified in studies with mouse and human ESCs [10,17–20] and demonstrated that almost all blood lineages, including red blood cells [21,22], neutrophils [13,23], megakaryocytes [24–26], lymphocytes [13,27–30], and dendritic cells [31–33] can be generated from these pluripotent cells. Recent work has shown that blood cells can be obtained from mouse iPSCs, as well [34,35]. The present work is aimed to demonstrate the hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation potential of different hiPSC lines, and determine whether the pattern of differentiation observed with hiPSCs is similar to hESCs. Our data demonstrated that subsets of cells with phenotype and hematopoietic and endothelial activity similar to corresponding hESC-derived counterparts are generated in OP9 coculture. These findings provide strong evidence that hiPSCs are very similar to hESCs, and differentiation systems established for hESCs can be readily applied to hiPSCs. While several issues remain to be resolved before hiPSC-derived blood cells can be administered to humans, hiPSCs can already be used for characterization of mechanisms of blood diseases and to identify molecules that can correct genetic networks.

Summary

We demonstrated that seven hiPSC lines are capable of differentiation into blood and endothelial cells with a differentiation pattern very similar to that observed with hESCs. Further transcriptional, epigenetic and functional in vivo analysis of iPSC-derived blood progenitors would be essential to determine the extent of possible applications of these cells for blood replacement therapies and bone marrow transplantation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr Toru Nakano for providing OP9 cells, Mitchell Probasco for assistance in the cell sorting, and Joan Larson for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by NIH grants HL081962 and HL085223 (to IS), and NIH grant P51 RR000167 to the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Footnotes

Author Contribution:

Kyung-Dal Choi, Giorgia Salvagiotto, Maxim Vodyanik: collection and assembly of data, conception and design, data analysis.

William Rehrauer: collection of data

James Thomson: conception, generation of iPSC lines

Junying Yu, Kim Smuga-Otto: generation of iPSC lines

Igor Slukvin: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

References

- 1.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. Epub 2006 Aug 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maherali N, Sridharan R, Xie W, et al. Directly reprogrammed fibroblasts show global epigenetic remodeling and widespread tissue contribution. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. Epub 2007 Jun 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. Epub 2007 Jun 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanna J, Markoulaki S, Schorderet P, et al. Direct reprogramming of terminally differentiated mature B lymphocytes to pluripotency. Cell. 2008;133:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aoi T, Yae K, Nakagawa M, et al. Generation of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Mouse Liver and Stomach Cells. Science. 2008;321:699–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1154884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. Epub 2007 Nov 1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. Epub 2007 Dec 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vodyanik MA, Thomson JA, Slukvin II. Leukosialin (CD43) defines hematopoietic progenitors in human embryonic stem cell differentiation cultures. Blood. 2006;108:2095–2105. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amit M, Carpenter MK, Inokuma MS, et al. Clonally derived human embryonic stem cell lines maintain pluripotency and proliferative potential for prolonged periods of culture. Developmental Biology. 2000;227:271–278. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vodyanik MA, Slukvin II. Chapter Hematoendothelial differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2007;(Unit 23.26) doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb2306s36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vodyanik MA, Bork JA, Thomson JA, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived CD34+ cells: efficient production in the coculture with OP9 stromal cells and analysis of lymphohematopoietic potential. Blood. 2005;105:617–626. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams BP, Daniels GL, Pym B, et al. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the OKa blood group antigen. Immunogenetics. 1988;27:322–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00395127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okita K, Nakagawa M, Hyenjong H, et al. Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells without viral vectors. Science. 2008;322:949–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1164270. Epub 2008 Oct 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stadtfeld M, Nagaya M, Utikal J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science. 2008;322:945–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1162494. Epub 2008 Sep 2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishikawa SI, Nishikawa S, Hirashima M, et al. Progressive lineage analysis by cell sorting and culture identifies FLK1+VE-cadherin+ cells at a diverging point of endothelial and hemopoietic lineages. Development. 1998;125:1747–1757. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy M, D'Souza SL, Lynch-Kattman M, et al. Development of the hemangioblast defines the onset of hematopoiesis in human ES cell differentiation cultures. Blood. 2007;109:2679–2687. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller G, Kennedy M, Papayannopoulou T, et al. Hematopoietic commitment during embryonic stem cell differentiation in culture. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:473–486. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zambidis ET, Peault B, Park TS, et al. Hematopoietic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells progresses through sequential hematoendothelial, primitive, and definitive stages resembling human yolk sac development. Blood. 2005;106:860–870. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4522. Epub 2005 Apr 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakano T, Kodama H, Honjo T. In vitro development of primitive and definitive erythrocytes from different precursors. Science. 1996;272:722–724. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu C, Hanson E, Olivier E, et al. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into hematopoietic cells by coculture with human fetal liver cells recapitulates the globin switch that occurs early in development. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:1450–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieber JG, Webb S, Suratt BT, et al. The in vitro production and characterization of neutrophils from embryonic stem cells. Blood. 2004;103:852–859. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eto K, Murphy R, Kerrigan SW, et al. Megakaryocytes derived from embryonic stem cells implicate CalDAG-GEFI in integrin signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:12819–12824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202380099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaur M, Kamata T, Wang S, et al. Megakaryocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells: a genetically tractable system to study megakaryocytopoiesis and integrin function. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:436–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takayama N, Nishikii H, Usui J, et al. Generation of functional platelets from human embryonic stem cells in vitro via ES-sacs, VEGF-promoted structures that concentrate hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 2008;111:5298–5306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117622. Epub 2008 Apr 5293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho SK, Webber TD, Carlyle JR, et al. Functional characterization of B lymphocytes generated in vitro from embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9797–9802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt TM, de Pooter RF, Gronski MA, et al. Induction of T cell development and establishment of T cell competence from embryonic stem cells differentiated in vitro. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:410–417. doi: 10.1038/ni1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woll PS, Martin CH, Miller JS, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived NK cells acquire functional receptors and cytolytic activity. J Immunol. 2005;175:5095–5103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galic Z, Kitchen SG, Kacena A, et al. T lineage differentiation from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11742–11747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604244103. Epub 12006 Jul 11714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senju S, Hirata S, Matsuyoshi H, et al. Generation and genetic modification of dendritic cells derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. Blood. 2003;101:3501–3508. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairchild PJ, Brook FA, Gardner RL, et al. Directed differentiation of dendritic cells from mouse embryonic stem cells. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1515–1518. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00824-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slukvin II, Vodyanik MA, Thomson JA, et al. Directed Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells into Functional Dendritic Cells through the Myeloid Pathway. J Immunol. 2006;176:2924–2932. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, et al. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318:1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. Epub 2007 Dec 1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schenke-Layland K, Rhodes KE, Angelis E, et al. Reprogrammed mouse fibroblasts differentiate into cells of the cardiovascular and hematopoietic lineages. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1537–1546. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0033. Epub 2008 May 1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.