Abstract

Two studies examined the effects of alcohol and relationship type on women’s sexual assault risk perception. Study 1 participants (N=62) consumed a moderate alcohol dose or non-alcoholic beverage, then rated their awareness of and discomfort with sexual assault risk cues in a hypothetical encounter with a new or established dating partner. Study 2 (N=351) compared control, placebo, low and high alcohol dose conditions using a similar scenario. Intoxicated women reported decreased awareness of and discomfort with risk cues. An established relationship decreased discomfort ratings. Findings indicate that alcohol may increase women’s sexual victimization likelihood through reduced sexual assault risk perception.

Keywords: Sexual Assault, Risk Perception, Alcohol Consumption

At least half of acquaintance sexual assaults occur after the victim, the assailant, or most commonly, both have been drinking (Abbey, Zawacki, Buck, Clinton, & McAuslan, 2004; Ullman, 1997). Early responding to risk can increase the possibility of a woman’s avoidance of sexual assault by leaving a dangerous situation before it escalates (Rozee, Bateman, & Gilmore, 1991). Therefore, understanding determinants of risk perception is an important area of inquiry. Risk appraisal can be compromised both by excessive alcohol consumption and by the type of relationship that a woman has with a man (Gidycz, McNamara, & Edwards, 2006). This paper presents two experimental studies of women's sexual assault-related risk perception examining the effects of both alcohol dosage and relationship type.

Detecting and feeling risk

Nurius and Norris (1996) presented a Cognitive Ecological Model of Women's Responses to Male Sexual Coercion. According to this model, women’s responses to male sexual coercion are mediated through cognitive processing of situational information. A woman first appraises the situation for the presence of risk and degree of threat. In other words a woman has to detect environmental cues that are associated with risk and then appraise them for their threat potential. After becoming aware of these environmental cues, the process of threat appraisal can result in feelings of discomfort (Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, 2001). Ultimately the appraisal process leads to evaluating the risks and benefits of responding to the threat, which determines the strength and type of women’s resistance.

Researchers have identified several factors associated with an increased likelihood of acquaintance sexual assault (Gidycz et al., 2006; Muehlenhard & Linton, 1987). To understand how women perceive a variety of sexual assault risk cues, Norris, Nurius, and Graham (1999) conducted a study in which women judged to what extent known risk factors made them feel “on guard.” Analyses showed that they clustered into two groups – clear and ambiguous. Clear, or unambiguous, sexual assault risk cues include direct actions by a man that indicate likely coercive or forceful sexual intent, such as brash sexual comments and persistent unwanted fondling (i.e., not taking no for an answer). Ambiguous cues include events or actions that are often a typical part of male-female social interactions, such as male-female size differential and an isolated setting. Norris et al. (1999) termed these cues “ambiguous” because in one situation, such cues could be completely innocuous, whereas in another, they could be harbingers of sexual assault (Muehlenhard & Linton, 1987).

Because of their alternative meanings, ambiguous cues can be particularly difficult to appraise. In reacting to risk cues, especially ambiguous ones, women may first attend to their most basic feelings of discomfort to determine whether they are at risk before they go on to make a full cognitive evaluation of whether further action is necessary. Norris et al. (1999) found that women develop feelings of being "on guard" in response to clear risk cues much more readily than they do to ambiguous ones, and such feelings can be an important source of information about how to react during the escalation of a threatening event. Because the different types of risk cues (ambiguous vs. clear) have been shown to result in different affective reactions, it is important to distinguish between these types of cues in assessments of women’s sexual assault risk perception.. Moreover, affective reactions to risk are especially influenced by the vividness of threat cues and their temporal proximity (Loewenstein et al., 2001). Thus, a situation that presents an increasing likelihood of harm over time, such as found in escalating male sexual aggression, is likely to evoke increasing feelings of discomfort as the risk cues shift from ambiguous to clear and the threat becomes more real and closer to fruition. For this reason, the present studies examined women’s feelings of discomfort regarding both ambiguous and clear risk cues. Additionally, because of the strong co-occurrence of alcohol consumption and sexual assault, we also investigated the extent to which alcohol consumption might influence women’s assessment of both clear and ambiguous risk cues.

Alcohol consumption and risk appraisal

Cognitive impairment models (Steele & Josephs, 1990; Taylor & Leonard, 1983) have been useful in explaining the effects of alcohol on risk judgments. These models state that as an individual becomes more intoxicated, the ability to process information from the environment deteriorates. Attention becomes more narrowly focused on the most salient cues. Several experimental studies have shown that moderate to high alcohol intoxication interferes with the ability to evaluate the consequences of high risk situations (Fromme, D'Amico, & Katz, 1999; Fromme, Katz, & D'Amico, 1997; Testa, Livingston, & Collins, 2000). However, no studies have examined what level of intoxication interferes with the detection of risk cues. This question is primary to understanding the process of risk appraisal. Because of alcohol’s established impairment effects on cognitive processes, we expected that detection of risk cues associated with sexual assault would be increasingly hampered as alcohol intoxication increased. Moreover, because clear risk cues are more salient and easier to interpret than ambiguous risk cues, we expected that alcohol intoxication would particularly compromise the perception of ambiguous sexual assault risk cues.

A second line of research important to understanding alcohol’s effects on threat appraisal involves its effects on affective responses. Alcohol consumption can reduce feelings of tension or anxiety (for a review see Greeley & Oei, 1999), a phenomenon known as tension reduction or stress response dampening (SRD). This effect has implications for risk appraisal to the extent that reactions to risk generate anxiety or feelings of internal discomfort. In his appraisal-disruption model of SRD, Sayette (1993) posits that alcohol consumption interferes with the ability to appraise stress or anxiety-related cues from the environment, if alcohol is consumed before the introduction of such cues. With decreased ability to process this information, an intoxicated person's stress response would be lower than if she or he were sober. The theory specifies that the SRD effect increases with greater impairment and is most likely to occur when stressors are difficult to appraise. Thus, alcohol-related SRD can be expected to attenuate feelings of discomfort with sexual assault risk cues, particularly ambiguous ones.

Alcohol consumption can also affect behavior through its learned, or expectancy, effects (Marlatt & Rohsenow, 1980), which can be examined by administering a placebo in place of a drink containing alcohol. Convincing subjects that they have consumed alcohol when they have not evokes previously learned expectations about alcohol’s effects on behavior. Any responses manifested as a result of consuming a placebo can be attributed to alcohol’s learned effects rather than to physiological ones. In their examination of alcohol’s physiological versus expectancy set effects on expected consequences of entering a potential sexual assault situation, Testa et al. (2000) found that a placebo increased women’s perceived benefits and decreased their perceptions of negative outcomes in a way similar to but weaker than an alcoholic beverage. Following this line of study, we examined alcohol expectancy set effects on women’s detection of and comfort with sexual assault risk cues.

Relationship and risk perception

Because sexual assaults often occur after a woman and a man have socialized together (Koss, 1988), it stands to reason that the closer a woman feels to a man, the less she would expect him to assault her (Gidycz et al., 2006). Actions that would evoke concern if committed by a newly met acquaintance might not do so if the couple was well acquainted. In an experimental study, VanZile-Tamsen, Testa, and Livingston (2005) compared the risk appraisals of women assigned to one of four levels of intimacy – just met, friend, date, or boyfriend - with a man who became sexually aggressive. They found that as intimacy level increased, women's judgments that the man posed a severe threat decreased. In a similar vein, we predicted that feelings of discomfort would vary as a function of relationship type.

Overview

Drawing on these converging theoretical underpinnings, two experiments were conducted to examine the effects of alcohol consumption and relationship type on women's awareness of and feelings of discomfort with sexual assault risk cues. In these studies female participants consumed an alcoholic, a placebo, or a control beverage and then projected themselves into a dating scenario that culminated in attempted sexual assault. Study 1 compared a moderate dose of alcohol (target BAC = .06%) to a control beverage, along with a casual versus a serious relationship. To determine whether alcohol effects occur at other dosages, Study 2 compared a placebo dose, a low (target BAC = .04%) dose, and a high dose (target BAC = .08%) of alcohol to a control. In an initial attempt to understand which of several relationship elements that were combined in Study 1 might be the key element in determining relationship effects, Study 2 held constant two of these – amount of prior consensual sex and future relationship prospects – and manipulated only length of the relationship (no previous dates versus four).

STUDY 1

Based on cognitive impairment models, we predicted that intoxicated women would be less likely to recognize risk cues, particularly ambiguous ones, than sober women. Previous work on SRD led us to predict that intoxicated women would express less discomfort with ambiguous cues than sober women would, but that clear risk cues, because of the greater ease with which they can be appraised, would not engender different levels of comfort. Finally, we predicted that, compared to those in the casual relationship condition, women in the serious relationship condition would report less discomfort overall.

Method

Participants

Participants were 62 women from a large western university who were recruited through an advertisement in the university newspaper. Participants’ mean (SD) age was 22.6 (2.1) years. Their self-reported ethnicity was 75% White, 20% Asian American, 3.3% African American, and 1.7% “other”. When women called the laboratory, they were given a brief description of the study by a female interviewer in which they were told that the study examined alcohol consumption and social interactions, involved the possible consumption of alcohol, and required approximately 3–4 hours of their time for which they would be paid $10 an hour. Participants were screened to ensure that they were free of health problems that would contraindicate alcohol consumption. Abstainers and heavy drinkers were also excluded. Scheduled participants were instructed not to drive to the lab, not to eat for four hours prior to the experimental session, and not to consume alcohol on that day. They received $10 per hour for their participation and an additional $5 for returning a mailed follow-up survey concerning their reactions to the study; no negative reactions were reported.

Procedure

Each participant was conducted through the study procedures individually by a female experimenter who checked the participant’s identification and verified her age and compliance with pre-experimental requirements. The participant signed an informed consent form and was weighed in preparation for the subsequent alcohol administration. To ensure that no alcohol would be administered to pregnant women, all alcohol condition participants completed a pregnancy screening. Each participant was then given an initial breathalyzer test (CMI Intoxilyzer 5000) to confirm that her blood alcohol concentration (BAC) was .00 %.

The experimenter then informed the participant of her beverage condition and poured three drinks, the contents of which differed according to experimental condition. Participants in the alcohol condition were administered .477 g ethanol per kg body weight in the form of 80-proof vodka mixed in a 1:4 ratio with orange juice. This dosage was chosen to reach a target peak BAC of .06 %. Control participants received an isovolemic amount of plain orange juice per kg body weight. Each participant was given three minutes to consume each drink and was told to pace her drinking evenly over the consumption periods.

During a fifteen-minute absorption period, breathalyzer tests were administered once every five minutes. The experimenter then gave the participant one of the stimulus stories and left the room so that she could read the story and complete the paper and pencil measures in privacy. The pre-story mean BAC was .047% (SD=.018), and the post-story mean BAC was .052% (SD=.011). Upon completion, the participant was offered food and water, debriefed, given a resource sheet listing available services for acquaintance rape victims, and paid. Participants who had consumed alcohol were required to remain in the laboratory until their BACs dropped below .03 %.

Materials

Stimulus story

The stimulus story was developed to portray a realistic social encounter between a man and a woman in which the man escalated his sexual demands over the course of the evening. The story was written in the second person (“You…”), and the participant was instructed to project herself into it as if it were happening to her at her current level of intoxication. In the casual dating relationship condition, the participant was described as having gone on a couple of dates with “Jeff,” as having a casual relationship with him, and as liking him but not being in love with him. In the story, the participant experienced uncertainty about how serious she would like the relationship to become. She and Jeff had kissed on their last date, but the story clearly described the participant as not wanting to have sex with him. In the serious dating relationship condition, the participant was described as having a boyfriend whom she had been dating for a couple of months. Their relationship was “getting serious,” and she believed she might be in love with him. Sexually, they had engaged in heavy petting, but she was clearly described as wanting to wait to have intercourse with him until they discussed their relationship together. She was depicted as wanting their relationship to last long-term.

The story then described a single dating episode between the participant and the male character. In the first part of the story, ambiguous risk cues were presented: the couple was isolated from others, the woman was dependent on the man for transportation, and the man was drinking alcohol. Previous research has demonstrated that similar circumstances commonly precede date rapes (Muehlenhard & Linton, 1987; Norris et al., 1999). In the second part of the story, clear risk cues were presented: continued unwanted sexual advances, the use of physical restraint, and verbal demands for intercourse. The woman’s response to the cues was not indicated in the story.

Dependent measures

The first assessment point occurred after the first part of the story; participants rated their awareness of and discomfort with the nine ambiguous risk cues that were presented in the story. The second assessment point occurred at the end of the story; at this point, participants rated their awareness of and discomfort with the six clear risk cues. For each cue, participants were first asked “How AWARE were you that this happened in the story?” and then asked “How COMFORTABLE did you feel about this while reading the story?” Awareness was rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0, completely unaware to 6, highly aware. Discomfort was rated on a scale ranging from 0, very comfortable, to 6, very uncomfortable.

Data Analytic Approach

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistical Software (version 11) for Windows. Inspection of the distributions of the awareness items revealed a high degree of negative skew. In general, participants rated themselves as being highly aware of the cues presented in the stories. The medians for all of the clear risk cue items and most of the subtle cue items were 6 on Likert scales ranging from 0 = "completely unaware" to 6 = "highly aware." This degree of skew precluded the use of customary parametric statistical analyses. Thus, Pearson chi-square analyses were performed to examine the data from two complementary perspectives. Within each assessment point, analyses investigated what proportion of participants: 1) endorsed a 6 (highest awareness) on all of the items combined (i.e., complete awareness of all cues); and 2) endorsed a 0 on any of the items (i.e., complete unawareness of at least one cue).

Inspection of the comfort items revealed reasonably normal distributions. Two scales were created from the discomfort items: discomfort with ambiguous cues (α = .91) and discomfort with clear cues (α = .87). A repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVAs) was conducted on the discomfort scales; Pillai’s trace was examined to determine multivariate significance. Where appropriate, Fisher’s LSD post hoc tests were conducted to determine which means differed from one another.

Results

Awareness of risk cues

Overall, 30.0% of women reported the highest awareness on every ambiguous risk cue item while 53.3% did so for clear risk cues. Conversely, 18.3% reported a complete lack of awareness of at least one ambiguous risk cue while only 3.3% did so for clear risk cues. As illustrated in Table 1, fewer intoxicated women than sober women reported complete awareness of all ambiguous risk cues. Additionally, a greater number of intoxicated women than sober women reported complete unawareness of at least one ambiguous risk cue. For clear risk cues, there were no significant differences between sober and intoxicated women's self-reports of awareness. Chi-square analyses comparing relationship condition for awareness of risk cues were also conducted; there were no significant findings for relationship condition.

Table 1.

Study 1. Percentage of women by alcohol condition reporting complete awareness of all cues and unawareness of one cue at each time point

| No Alcohol (n = 30) |

Alcohol (n = 30) |

χ2(1) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambiguous Risk Cues | ||||

| Complete awareness of all cues | 43.3 | 16.7 | 5.08 | .024 |

| Complete unawareness of at least one cue | 6.7 | 30.0 | 5.46 | .020 |

| Clear Risk Cues | ||||

| Complete awareness of all cues | 63.3 | 43.3 | 2.41 | ns |

| Complete unawareness of at least one cue | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0.00 | ns |

Discomfort with risk cues

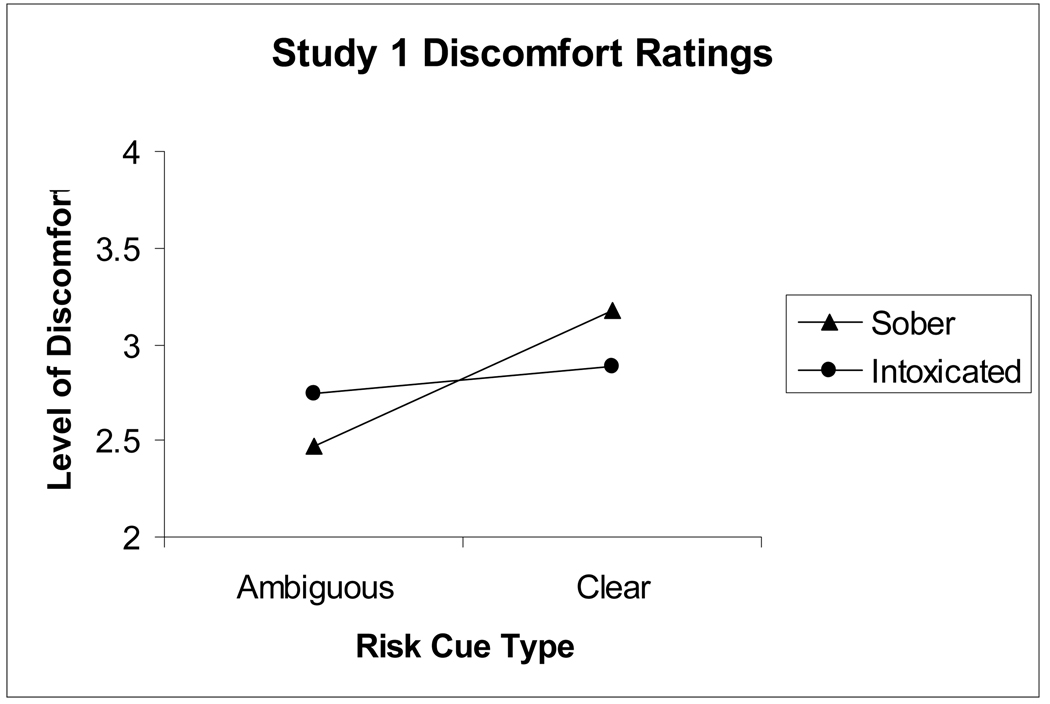

The repeated measures MANOVA on the discomfort scales revealed a significant multivariate two-way interaction of alcohol condition by cue type, F (1, 56) = 4.96, p < .05. As depicted in Figure 1, a post hoc examination of the means indicated that sober women reported greater discomfort with the clear risk cues than the ambiguous risk cues. Intoxicated women reported similar levels of discomfort for both types of cues. Additionally, there was a significant between-subjects main effect for relationship condition (F (1, 56) = 13.53, p = .001), with women in the casual relationship condition (M = 3.36) reporting greater overall discomfort than did women in the serious relationship condition (M = 2.27). There were no other significant effects.

Figure 1.

Study 1 Discomfort Ratings as a Function of Alcohol Condition and Cue Type.

Discussion

Hypotheses for this study were partially supported. Consistent with cognitive impairment models, a moderate dose of alcohol appeared to interfere with recognition of ambiguous, but not clear, risk cues. Moreover, while sober women become increasingly uncomfortable as the risk cues became clearer, intoxicated women showed no such increase in discomfort, perhaps indicating a stress response dampening effect. As expected, too, women in the serious relationship condition expressed greater comfort overall with both ambiguous and clear risk cues compared to those in the casual relationship condition.

It is possible that the alcohol dosage examined in this study was insufficient to interfere with recognition of clear risk cues but more than sufficient to interfere with recognition of ambiguous risk cues. Additionally, because the moderate alcohol dosage used in this study appears to have achieved a SRD effect regarding levels of comfort, it was unclear if a lesser alcohol dosage might achieve a similar effect. Consequently, Study 2 employed both a lower and a higher dosage level than that employed in Study 1. A placebo condition was also used to examine the influence of alcohol expectancy effects on women’s sexual assault risk perception. The relationship manipulation used in this study combined elements of both intimacy level and length of the relationship; Study 2 was limited to examining only length of relationship.

STUDY 2

The second study was designed to examine in more depth the effects of alcohol on risk awareness and discomfort, as well as to deconstruct which elements of the relationship factor played a role in decreasing discomfort level. First, we expanded the range of alcohol dosages to include a control dose (BAC = .00%), a low dose (target BAC = .04%, approximately 2–3 drinks), and a high dose that represent the legal limit for driving in the United States (target BAC = .08%, approximately 4–5 drinks). This range permitted us to evaluate the effects of two additional dosages - one above and one below the dosage used in Experiment 1. Second, we also included a placebo condition (actual BAC = .00%, expected BAC = .04%) in order to test whether a woman’s psychological set or belief that she is drinking alcohol could lead to both ignoring signs of potential danger and increased comfort with the situation. Third, because in Study 1 level of commitment and length of relationship were conflated, this study kept commitment level constant, while varying the number of dates the couple had been on. As in Study 1, we hypothesized that intoxicated women would be less likely to recognize both ambiguous and clear risk cues than sober women. We expected that this effect would be more pronounced at the higher dosage and nonexistent with a placebo. Similarly we predicted that discomfort ratings would decrease across dosage levels, with no differences between control and placebo. Finally, we predicted that women in the established relationship condition would express less discomfort than women in the new relationship condition.

Method

Participants

Participants in Study 2 were 351 women 21 to 35 years of age, recruited from both the university, as in Study 1, and the community, through advertisements in local and campus newspapers and posted flyers. Telephone screening excluded potential participants who were currently in a steady relationship, or who reported no interest in having a relationship with a man, to ensure that all participants would find the stimulus story relevant to their current social dating status. Callers with medical conditions contraindicating alcohol consumption, abstainers, and heavy drinkers were again screened out, and participants were given the same pre-experimental guidelines about eating, consuming alcohol, and driving.

Participants’ mean age was 24.8 years (SD = 3.8). Fifty-three percent were non-students; 68% were employed. Their self-identified ethnicities were 79% European-American, 8% Asian/Pacific Islander, 5% multi-racial or other, 5% Latina, 3% African-American, and 1% Native American. Participants were paid $10 per hour for two laboratory sessions, with total payment ranging from $25 to $75. As in Study 1 participants received an additional $5 for returning a mailed follow-up survey; no negative reactions were reported.

Procedure

The procedure consisted of two laboratory sessions spaced at least one week apart: a questionnaire session and an experimental session. Two sessions were used to minimize the effect of exposure to the background questionnaires. The second occurred a mean of 14.1 days (SD = 19.3) after the first. Both were conducted by female experimenters.

Questionnaire session

As in Study 1, a female experimenter checked the participant’s identification and obtained informed consent. The experimenter explained the computerized questionnaires to the participant and left the room to provide maximum privacy. Upon completion, the participant was debriefed, paid $10.00, and scheduled for the second session.

Experimental session

All procedures for the alcohol administration protocol were identical to those of Study 1 except for the following. Women assigned to the .04% target BAC received .325 g ethanol per kg body weight while those assigned to the .08% condition received .681 g ethanol per kg body weight. After a 5-minute initial absorption period, low-dose participants were breathalyzed approximately every 2 minutes until they reached a criterion BAC of .025%; high dose participants were breathalyzed approximately every 5 minutes until they reached a criterion BAC of .055%. These criterion BACs were selected to insure that participants began reading the stimulus story while their BACs were ascending. Post-story mean BACs were .035% (SD = .008) for low dose participants and .076% (SD = .011) for high dose.

To control for variation in the time it took participants in the alcohol conditions to reach their criterion BACs, each participant in an alcohol condition had a no-alcohol participant yoked to her timeframe. The yoked control participant began reading the same story containing the same relationship condition after the same amount of time as her counterpart in the alcohol condition. The control participant was breathalyzed at the same intervals as the alcohol participant to whom she had been yoked to control for the physical exertion of breath analysis (Giancola & Zeichner, 1997). Each placebo participant also had a corresponding control participant yoked to her timeframe.

In the placebo condition, flat tonic with a small amount of vodka mixed in was substituted for vodka. Several steps were taken to enhance the deception. The experimenter informed the participant that she had been randomly assigned to the low alcohol condition. To blunt the participant’s ability to taste and discern the absence of alcohol, she was directed to rinse with a non-alcoholic cinnamon-mint mouthwash, ostensibly to allow a more accurate breathalyzer reading. To enhance the odor of alcohol, the placebo beverage cup was misted with vodka out of view of the participant, and a trace amount of vodka was floated on top of the beverage, disguised as a squirt of pure lime juice. The breath alcohol analyzer was rigged to print out a card bearing a bogus BAC of .027%, which was shown and read aloud to the participant.

After beverage administration, the experimenter left the room, and the participant completed the dependent measures in private. At the end of the session, the participant was offered food and water, debriefed, and provided a resource list for acquaintance rape victims. Control and placebo participants were then paid and released; alcohol-receiving participants remained in the lab until their BACs fell below .03%. Special care was taken in debriefing those who had been assigned to the placebo condition to explain the necessity of the deception.

Materials

Stimulus story

The stimulus story used for Study 1 was modified for Study 2 to refine the relationship variable and maximize the realism of the situation described in the story. Based on feedback from 18 pilot participants, who were interviewed after reading the story, minor changes were made, including changing the setting, some wording choices, and the characters’ names. The story retained the same basic organization whereby similar ambiguous cues were presented in the first part while similar clear risk cues were presented in the second part.

The two types of prior relationship between the woman and the male story character (Michael) were operationalized as the number of dates they had hypothetically had. In both relationship conditions (new = 0 dates vs. established = 4 dates in the past month), the woman was clearly portrayed as being interested in having it become long-term, but the couple had had no sexual contact beyond kissing. This change allowed new and established relationships to be examined while controlling for prior level of sexual intimacy. Whether the woman consumed alcohol in the story was matched with whether the participant had been randomly assigned to receive alcohol in the laboratory; alcohol- and placebo-receiving participants were portrayed as drinking alcohol in the story whereas controls were portrayed as drinking soft drinks. The participant was told to project herself into the story at her current level of intoxication. As in Study 1, awareness and discomfort were assessed at two points: ambiguous cues were rated after the first part of the story while clear risk cues were rated at the end of the story.

Dependent measures

At the first assessment point, participants rated their awareness of and discomfort with eight ambiguous risk cues similar to those in Study 1. At the second assessment point, participants rated their awareness of and discomfort with six clear risk cues also similar to those in Study 1. For each cue, participants were first asked “How AWARE were you that this happened in the story?” and then asked “How COMFORTABLE did you feel about this while reading the story?” Awareness was rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0, completely unaware to 6, highly aware.1 All participants received each of the items assessing awareness; however, unlike in Study 1, only those women who indicated awareness greater than zero for any particular cue received the corresponding comfort question for that cue. Discomfort was rated on a scale ranging from 0, completely uncomfortable, to 6, completely comfortable. Responses were recoded for analysis so that, as in Study 1, higher scores indicated higher discomfort. For the discomfort subscales, alphas were .80 for the ambiguous cues, .90 for the clear risk cues,

Results

Participants completed manipulation checks regarding alcohol consumption and relationship condition. For alcohol consumption, participants were asked “In terms of alcohol content, how many alcoholic drinks was the beverage you consumed here today equivalent to?” All participants passed manipulation checks for alcohol condition, meaning that women in the control beverage condition reported consuming no alcohol, while women in the placebo, low dose, or high dose conditions reported having consumed at least one alcoholic drink. For relationship condition, participants were asked “In the story, how involved were you with Michael?”, with the response options of knew him from Susan’s house, but hadn’t dated and knew him from Susan’s house and had gone on 4 dates. Six women, five in the control condition and one in the placebo condition, failed manipulation check for relationship condition and were excluded from further analyses. The remaining sample consisted of 345 women. Mean pre- and post-story BACs were .030% and .032% in the low dose condition and .059% and .070% in the high dose condition, respectively.

Data analytic approach

Distributions of items were very similar to those found in Study 1; thus, the same general data analytic approach was used but expanded upon due to the multiple beverage conditions. Preliminary Pearson chi-square analyses were conducted to screen for placebo effects on the awareness variables; women in the placebo condition were compared to the subset of controls to whom they had been yoked (i.e. matched on beverage protocol time), irrespective of relationship condition assignment. No placebo effects were found; thus, the control and placebo groups were combined for subsequent analysis of the awareness. This provides a highly conservative test for physiological alcohol effects because the combined control/placebo group simultaneously controls for random and alcohol expectancy effects. Logistic regression analyses were then used to examine the independent and interactive effects of the alcohol intoxication and relationship type on awareness. The alcohol variable corresponded to the dosage of alcohol received: 0 for control and placebo participants, 1 for those dosed to reach .04%, and 2 for those dosed to reach .08%. The alcohol and relationship variables were entered on step 1, and their interaction was entered on step 2. The interaction was not found to be a significant predictor for any dependent variable; therefore, results are presented for step 1 only.

Awareness of risk cues

Overall, 18.8% of women reported complete awareness of ambiguous risk cues while 50.4% did so for clear risk cues. On the other hand, 24.9% reported complete unawareness of at least one ambiguous risk cue while only 7.2% did so for clear risk cues. Results of logistic regression analyses are shown in Table 2. Increasing intoxication was associated with lower likelihood of complete awareness of all ambiguous risk cues (OR = 0.204, p < .001) and higher likelihood of complete unawareness of at least one ambiguous risk cue (OR = 1.807, p = .022). There were no alcohol effects for awareness of clear risk cues. Additionally, there were no significant effects of relationship type on either ambiguous or clear risk cues.

Table 2.

Study 2. Results of logistic regression analyses.

| Wald | Omnibus | HLT | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE B | χ2 | p | OR | χ2 | p | χ2 | p | C-S R2 | N R2 | |

| Ambiguous Cues | ||||||||||||

| Awareness | Alcohol | −1.59 | 0.42 | 14.32 | .000 | 0.204 | ||||||

| Relationship | −0.55 | 0.29 | 3.59 | .058 | 0.579 | |||||||

| Constant | −0.87 | 0.19 | 19.85 | .000 | 0.420 | |||||||

| Model | 22.81 | < .001 | 0.19 | .909 | .064 | .103 | ||||||

| Unawareness | Alcohol | 0.59 | 0.26 | 5.23 | .022 | 1.807 | ||||||

| Relationship | 0.26 | 0.25 | 1.10 | .294 | 1.302 | |||||||

| Constant | −1.44 | 0.21 | 48.32 | .000 | 0.236 | |||||||

| Model | 6.20 | .045 | 0.00 | 1.000 | .018 | .026 | ||||||

| Clear Risk Cues | Alcohol | −0.35 | 0.23 | 2.24 | .135 | 0.707 | ||||||

| Awareness | Relationship | −0.04 | 0.22 | 0.03 | .866 | 0.964 | ||||||

| Constant | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.75 | .387 | 1.157 | |||||||

| Model | 2.27 | .321 | 2.86 | .240 | .007 | .009 | ||||||

| Unawareness | Alcohol | −0.43 | 0.49 | 0.80 | .372 | 0.648 | ||||||

| Relationship | −0.96 | 0.46 | 4.38 | .036 | 0.382 | |||||||

| Constant | −2.05 | 0.28 | 54.93 | .000 | 0.128 | |||||||

| Model | 5.63 | .060 | 3.08 | .214 | .016 | .040 | ||||||

Note. HLT = Hosmer and Lemeshow Test, C-S R2 = Cox and Snell R-Squared; N R2 = Nagelkerke R-Squared. Predictor χ2 statistics are evaluated with 1 degree of freedom. Model χ2 statistics are evaluated with 2 degrees of freedom.

Discomfort with risk cues

Repeated measures MANOVA on the discomfort scales revealed a significant multivariate main effect for cue type, F (1, 337) = 71.03, p < .001. Participants were significantly more uncomfortable with the clear risk cues (M = 2.65) than with the ambiguous risk cues (M = 2.06). There was also a significant main effect for relationship, F (1, 337) = 13.23, p < .001. Participants in the new relationship condition (M = 2.56) were significantly more uncomfortable than those in the established relationship condition (M = 2.15). These main effects were qualified by a significant cue type by relationship interaction, F (1, 337) = 4.75, p = .030; inspection of the means showed that the increase in discomfort from ambiguous to clear risk cues was blunted in the established relationship condition (ambiguous M = 1.93, clear M = 2.37) compared to the new relationship condition (ambiguous M = 2.20, clear M = 2.93). Aside from these effects, the main effect for alcohol condition was significant, F (3, 337) = 3.75, p = .011. Post-hoc tests indicated that low- (M = 2.22) and high-dose participants (M = 2.13) did not differ but reported significantly less (p < .05) discomfort than control participants did (M = 2.53). Placebo participants (M = 2.55) did not differ from control participants but reported significantly more discomfort than high-dose participants did (p < .05) and marginally more discomfort than low-dose participants (p < .057).

Discussion

Similar to Study 1, in this study alcohol consumption interfered with awareness of ambiguous risk cues but not clear risk cues. No differences were found by dose. Alcohol also decreased feelings of discomfort across both ambiguous and clear risk cues, but again these findings not vary significantly by dose. Although the findings for this study are once again consistent with a cognitive impairment interpretation of risk cue recognition, the lack of a dosage effect did not extend findings from Study 1.

Also consistent with Study 1, those in the established relationship condition expressed less discomfort overall than those in the new relationship condition. Moreover, women in the new relationship became increasingly uncomfortable as the risk cue became clearer, but women in the established relationship condition showed no such effect. Thus, the length of a relationship appears to be an important element in women feeling more comfortable with a man’s sexual advances, even as they become more clearly risky.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Using Nurius and Norris’s (1996) Cognitive Ecological Model as a theoretical foundation, these experiments examined two situational factors that were expected to influence women’s cognitive appraisals of sexual assault risk cues. A consistent pattern of relationships emerged among alcohol, type of relationship, and awareness of and discomfort with sexual assault risk cues indicating that two types of alcohol effects may influence different aspects of risk appraisal. Whereas detection of risk cues was affected by cognitive impairment related to alcohol (Steele & Josephs, 1990), affective reactions were seemingly influenced by alcohol’s anxiolytic effects (Sayette, 1993). While further research is needed to replicate and build upon these findings, these results point to the importance of taking a multifaceted approach to the investigation of risk appraisal.

Alcohol and risk appraisal

In both studies a smaller proportion of intoxicated women reported complete awareness of ambiguous risk cues than did sober women, and a larger proportion of intoxicated women also reported complete unawareness of at least one ambiguous risk cue. Thus alcohol consumption made it less likely that women would be maximally aware of ambiguous risk cues and more likely that women would be minimally aware of at least one. It thus appears that alcohol myopia effects impaired the intoxicated women’s perception of less salient ambiguous cues that might indicate increased sexual assault risk (Steele & Josephs, 1990). Alcohol did not, however, diminish women’s perceptions of clear sexual assault risk cues, indicating that at these levels of intoxication, these clear risk cues had enough salience for both sober and intoxicated women to perceive them equally. That these effects did not occur when manipulating the expectation of drinking is another clear indication that cognitive impairment, rather than learned associations between alcohol consumption and ambient cues related to male-female socializing, is instrumental in the detection of risk cues.

This finding is consistent with earlier research on evaluating risk. Previous studies have demonstrated that cognitive impairment resulting from alcohol intoxication interferes with the cognitive evaluation of risk (Fromme et al., 1997; Fromme et al., 1999; Testa et al., 2000). The present studies have shown that, even at a basic level of cue recognition, a BAC as low as .04% can dampen the ability to recognize key environmental events associated with a potential sexual assault. Thus, the entire process of cognitive appraisal of risk – from recognition of cues to cognitively evaluating their consequences – appears to be hampered by alcohol’s physiological impairment effects even at fairly low doses.

The impairment of risk perception when intoxicated may account for some of the relationship between alcohol consumption and sexual assault. Because intoxicated women are less likely than sober women to perceive risk early in the situation when cues are typically ambiguous, they may also be less likely to take precautions early in the dating episode, thereby increasing their vulnerability as the situation progresses (Abbey, 1991). Sober women who have the cognitive capacity to detect ambiguous risk cues early in the situation may have a greater opportunity to avoid potential danger before the situation develops beyond their control (Rozée, et al., 1991). Thus, intoxicated women, even at fairly low levels of intoxication, may be more likely to be assaulted than sober women because they cannot be proactive through an early perception of ambiguous risk indicators. They may only recognize that they are at risk once it is too late to engage in effective risk reduction measures.

In Study 1, only sober women evidenced increased discomfort as sexual aggression cues escalated; intoxicated women did not feel more uncomfortable even as the risk in the situation grew clearer. In Study 2, intoxicated women reported less discomfort overall than did sober women. These findings are consistent with a stress response dampening (i.e. anxiety reduction) explanation (Sayette, 1993). Because the detection of risk was disrupted by alcohol consumption, feelings of discomfort or anxiety that would have otherwise been generated may have been dampened. Although there were no dosage effects, the lack of an expectancy effect provides further support for this model's relevance to these findings.

The applicability of the SRD model to alcohol-involved sexual victimization has implications for women's ability to defend themselves against sexual aggression that occurs in the context of consuming alcohol. Unless a woman is able to recognize events that put her in danger, she will not be able to mount an effective resistance to a sexual assault (Rozee et al., 1991). Beyond recognizing that potentially threatening actions are occurring, women also need to sense that these events are not in her best interest. Even a small increase in her comfort with sexual aggression might delay taking any defensive action. Thus, women need to become informed about how alcohol consumption, even at low dosages, might prevent reacting in a self-protective manner to risk cues and thus could lead to ineffective resistance to a sexual assault.

The role of relationship

Although type of relationship did not affect awareness of either ambiguous or clear risk cues, as expected, women in the established relationship condition expressed more comfort with both ambiguous and clear risk cues. This is consistent with VanZile et al.'s (2005) finding that degree of intimacy with a man was related to decreased judgments of threat severity. It is not surprising that a woman would feel more comfortable with a well-acquainted man than with one who is less well-known. Unfortunately this may work to her detriment in the case where a man more familiar to her betrays her trust by sexually assaulting her. In this type of situation a woman might feel completely caught off guard and thus may experience considerable delay in expressing her lack of consent, let alone outright resistance. Especially telling is the Study 2 finding that only women in the new relationship condition reported increased discomfort as risk cues became clearer; women in the established relationship condition did not report growing discomfort even in the face of clear sexual assault risk cues. This result in particular highlights the importance of examining types of risk cues, in that it provides more specific information about how relationship context influences particular facets of sexual assault risk perception and thus suggests potential targets for intervention programming.

Our results suggest that it is important for sexual assault risk reduction programs to convey to women the need to be vigilant about both their alcohol consumption and their dating partners. It is also essential to convey to men how alcohol influences perception, the power this gives them in dating situations, and the ultimate responsibility they bear for preventing sexual assault. Rape risk reduction programs face challenges in addressing the role of alcohol in young adult dating relationships, particularly given the strong, typically positive, association between alcohol consumption and sexual relationships in Western culture (George & Stoner, 2000). However, because our results indicate that women’s sexual assault risk perception may be hampered at even low levels of alcohol consumption, these efforts remain critical.

Although a laboratory situation is limited in how realistically it can convey the events leading up to a potential sexual assault, the ability to control the dosage and the timing of an alcoholic beverage can help to elucidate the role of alcohol in such a situation. Thus, as with previous studies (Fromme et al., 1997; Fromme et al., 1999; Maisto, Carey, Carey, Gordon, & Schum, 2004; Testa et al., 2000), experimental methodology provides the opportunity to draw causal inferences about alcohol’s effects on women’s judgments of risky events. Nevertheless, caution should be taken in interpreting and generalizing these findings to situations outside the laboratory. Despite their limitations, these findings contribute to understanding in part the processes by which women’s alcohol consumption may influence detection of and affective reactions to sexual assault risk. Given the high prevalence of alcohol-facilitated sexual assault, continued research that further delineates these processes is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants AA12219 to Jeanette Norris and AA13565 to William H. George.

Biographies

Kelly Cue Davis, Ph.D. is a Research Assistant Professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Washington. She received her doctorate in clinical psychology in 1999 from the University of Washington. Dr. Davis currently serves as Chair of the Society for the Psychology of Women’s Task Force on Violence against Women. Dr. Davis has received both foundation and federal grants to support her research, which investigates the effects of alcohol on sexual decision making, sexual risk taking, sexual violence, and sexual health.

Susan A. Stoner received her Ph.D. in clinical psychology from the University of Washington in 2003. Formerly a research scientist in the Psychology Department at the University of Washington, she is now a research scientist at Talaria, Inc. Her primary research focus is along the nexus of alcohol use, relationships, sexuality, decision-making, and health.

Jeanette Norris, Ph.D. is a senior research scientist at the University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute. She received her doctorate in social psychology from the University of Washington in 1983 and has conducted research on sexual issues for more than twenty years. Her current research interests include the effects of alcohol consumption on sexual assault victimization and perpetration, as well as alcohol's effect on high risk sexual decision making.

William H. George, Ph.D. is Professor of Psychology and Adjunct Professor of American Ethnic Studies at the University of Washington. He completed his doctorate in clinical psychology and his postdoctoral training in addictive behaviors at the University of Washington in 1984. Between 1984 and 1991, he served as Assistant to Associate Professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo. Dr. George is also Director of the UW’s Institute for Ethnic Studies in the United States, which funds intramural faculty grants and an Associate Editor for the journal Psychology of Addictive Behaviors.

Tatiana Masters is a doctoral candidate in social welfare at the University of Washington in Seattle. Her dissertation research articulates how macro-level gendered sexual norms that limit female agency and choice in heterosexual negotiations are enacted or resisted at the micro-level of an individual woman or sexual interaction, using mixed methods to theorize female sexual agency and investigate its implications for preventing STIs and HIV. Tatiana's doctoral training is supported by a fellowship from the National Institute of Mental Health (F31 MH078732-01).

Footnotes

At the first assessment point, two cues that did not occur in the story were included as validity items; 1 participant endorsed awareness above the midpoint of the scale on both items. Analyses were repeated with this participant excluded, and the pattern of results was unaffected; therefore, her data were retained for the presented analyses.

Contributor Information

Kelly Cue Davis, Email: kcue@u.washington.edu, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 4101 15th Ave NE, Box 354900, Seattle, WA 98105 USA; Voice: 206.616.2174 Fax: 206.543.5760.

Susan A. Stoner, Email: sstoner@talariainc.com, Talaria, Inc., 1121 34th Ave, Seattle, WA 98122 USA; Voice: 206.748,0443 ex.22 Fax: 206.748.0504.

Jeanette Norris, Email: norris@u.washington.edu, Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute, University of Washington, 1107 NE 45th Street, Suite 120, Seattle, WA 98105-4631 USA, Voice: 206.685.3835 Fax: 206.543.5473.

William H. George, Email: bgeorge@u.washington.edu, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Box 351525, Seattle, WA 98195 USA; Voice: 206.543-6792 Fax: 206.543.5760.

N. Tatiana Masters, Email: tmasters@u.washington.edu, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 4101 15th Ave NE, Box 354900, Seattle, WA 98105 USA; Voice: 206.685.1748, Fax: 206.543.5760.

REFERENCES

- Abbey A. Acquaintance rape and alcohol consumption on college campuses: How are they linked? Journal of American College Health. 1991;39:165–169. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck P, Clinton AM, McAuslan P. Sexual assault and alcohol consumption: What do we know about their relationship and what types of research are still needed? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9:271–303. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00011-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, D'Amico EJ, Katz EC. Intoxicated sexual risk taking: An expectancy or cognitive impairment explanation? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:54–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Katz E, D'Amico E. Effects of alcohol intoxication on the perceived consequences of risk taking. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1997;5:14–23. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Stoner SA. Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behavior. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2000;11:92–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Zeichner A. The biphasic effects of alcohol on human physical aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:598–607. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, McNamara JR, Edwards KM. Women's risk perception and sexual victimization: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:441–456. [Google Scholar]

- Greeley J, Oei TPS. Alcohol and tension reduction. In: Leonard K, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 1999. pp. 14–53. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP. Hidden rape: Incidence, prevalence, and descriptive characteristics of sexual aggression in a national sample of college students. In: Burgess AW, editor. Sexual Assault. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Garland; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein GF, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N. Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:267–286. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Schum JL. Effects of alcohol and expectancies on HIV-related risk perception and behavioral skills in heterosexual women. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12:288–297. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Rohsenow DJ. Cognitive processes in alcohol use: Expectancy and the balanced placebo design. In: Mello NK, editor. Advances in Substance Abuse. Vol. 1. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, Inc; 1980. pp. 159–199. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard CL, Linton MA. Date rape and sexual aggression in dating situations: Incidence and risk factors. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34:186–196. [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Nurius PS, Graham TL. When a date changes from fun to dangerous: Factors affecting women's ability to distinguish. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:230–250. doi: 10.1177/10778019922181202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurius PS, Norris J. A cognitive ecological model of women's response to male sexual coercion in dating. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 1996;8:117–139. doi: 10.1300/J056v08n01_09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozee PD, Bateman P, Gilmore T. The personal perspective of acquaintance rape prevention: A three-tier approach. In: Parrot A, Bechhofer L, editors. Acqaintance Rape: The Hidden Crime. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 1991. pp. 337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA. An appraisal-disruption model of alcohol's effects on stress responses in social drinkers. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:459–476. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP, Leonard KE. Alcohol and human physical aggression. In: Geen RG, Donnerstein EJ, editors. Aggression: Theoretical and Empirical Reviews, Issues in Research. Vol. 2. New York: Harper Collins; 1983. pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, Collins RL. The role of women's alcohol consumption in evaluation of vulnerability to sexual aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:185–191. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Review and critique of empirical studies of rape avoidance. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1997;24:177–204. [Google Scholar]

- VanZile-Tamsen C, Testa M, Livingston JA. The impact of sexual assault history and relational context on appraisal of and responses to acquaintance sexual assault risk. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:813–832. doi: 10.1177/0886260505276071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]