Abstract

Reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines contribute to cardiovascular diseases. Inhibition of downstream transcription factors and gene modifiers of these components are key mediators of hypertensive response. Histone acetylases/deacetylases can modulate the gene expression of these hypertrophic and hypertensive components. Therefore, we hypothesized that long-term inhibition of histone deacetylase with valproic acid might attenuate hypertrophic and hypertensive responses by modulating reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines in SHR rats. Seven week-old SHR and WKY rats were used in this study. Following baseline blood pressure measurement, rats were administered valproic acid in drinking water (0.71% wt/vol), or vehicle, with pressure measured weekly thereafter. Another set of rats were treated with hydralazine (25mg/kg/day orally) to determine the pressure-independent effects of HDAC inhibition on hypertension. Following 20 weeks of treatment, heart function was measured using echocardiography, rats were sacrificed and heart tissue collected for measurement of total reactive oxygen species as well as pro-inflammatory cytokine, cardiac hypertrophic and oxidative stress gene and protein expressions. Blood pressure, pro-inflammatory cytokines, hypertrophic markers and reactive oxygen species were increased in SHR versus WKY rats. These changes were decreased in valproic acid treated SHR rats, while hydralazine treatment only reduced blood pressure. These data indicate that long-term histone deacetylase inhibition, independent of the blood pressure response, reduces hypertrophic, pro-inflammatory and hypertensive responses by decreasing reactive oxygen species and angiotensin-type1 receptor expression in the heart, demonstrating the importance of uncontrolled histone deacetylase activity in hypertension.

Keywords: Ang II, cardiac hypertrophy, cytokines, hypertension, oxidative stress, HDAC

Introduction

Essential hypertension is a condition associated with increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (PICs)1, 2. Studies from our lab and others have shown that PICs lead to an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS), which up-regulates Nuclear Factor-kappaB (NFκB) activity, thus further increasing PIC and ROS transcription and amplifying their subsequent actions3–5. Along with renin-angiotensin system (RAS) components, PICs also activate hypertrophic mediators, which can result in cardiac hypertrophy and altered cardiac remodeling and function6, 7.

There are many triggers of hypertensive-induced inflammation resulting in both hypertrophic and hypertensive responses, many of which are through transcription factor NFκB activation, ultimately resulting in alterations of gene transcription and perpetuation of the hypertensive state5, 8. In order for transcription factors such as NFκB to activate their target genes, DNA and chromatin remodeling must occur. Post-translational modifications of histone cores through a tightly regulated addition/removal of an acetyl tag on their N-terminal tails plays a major role in gene expression modulation9. These additions/removals are accomplished by several members of the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and histone deacetylase (HDAC) families, which either open or close DNA strands to the actions of transcription factors10, 11.

Normally, this balance is tightly controlled, but during conditions of stress and inflammation, activation of PICs can result in increased HDAC activation and histone acetylation, correlating with an increase in NFκB activity and further increases in PIC expression, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) and the interleukins (ILs) 12, 13. Though HDACs would appear to repress inflammatory responses through reduced gene expression, this view is too simplistic in regards to their non-histone protein acetylation/deacetylation abilities, often times having quite opposite effects in regards to the inflammatory response14–17.

Recent evidence indicates that the various HDAC classes respond differently towards inducing cardiac hypertrophy in non-hypertensive animal models16, 18, 19 and that global HDAC inhibition (HDACi) can prevent these hypertrophic changes20. However, it is not known whether HDACi protects against cardiac hypertrophy and hypertensive response by modulating PICs and oxidative stress in spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats. A previous study used valproate, a derivative of valproic acid (VPA), to study hypertension in SHR rats. Though they showed a reduction in systolic blood pressure21, the treatment was only carried out to 9 weeks of age, which is still 3 weeks too young to display the full systemic changes associated with hypertension in this animal model, including cardiac hypertrophy and inflammation. This study was established to assess the role of HDAC blockade on the inflammatory response and its effect on the pathogenesis of hypertension. Therefore, we hypothesize that chronic HDACi will attenuate the inflammatory and hypertensive responses associated with the hypertensive state. To test this, we administered VPA, a fairly novel HDAC inhibitor22, especially Class I HDACs, as a long-term treatment in SHR rats, for assessment of inflammatory, hypertrophic and hypertensive changes associated with essential hypertension.

Materials and Methods

All the procedures in this study were approved by the Louisiana State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Animals and Experimental Design

Male Wistar-Kyoto (WKY; n=20) and SHR (n=20) rats were randomly assigned to vehicle (water) or VPA (0.71% wt/vol23, dissolved in water, prepared and provided daily) treatment groups. Another set of rats were treated with hydralazine (HYD; 25mg/kg/day in drinking water8). Rats received drug or vehicle for 20 weeks starting from 7 weeks of age. Rats were euthanized at 27 weeks of age with left ventricular (LV) tissue collected for molecular analyses. We performed the following experimental procedures: blood pressure measurements, echocardiographic analysis, real time RT-PCR, western blot analysis, electron paramagnetic spin resonance (EPR) studies, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA), colorimetric assays, immunofluorescence, immunohistochemical and statistical analysis. For an expanded Materials and Methods section, please see the online Data Supplement at http://hyper.ahajournals.org.

Results

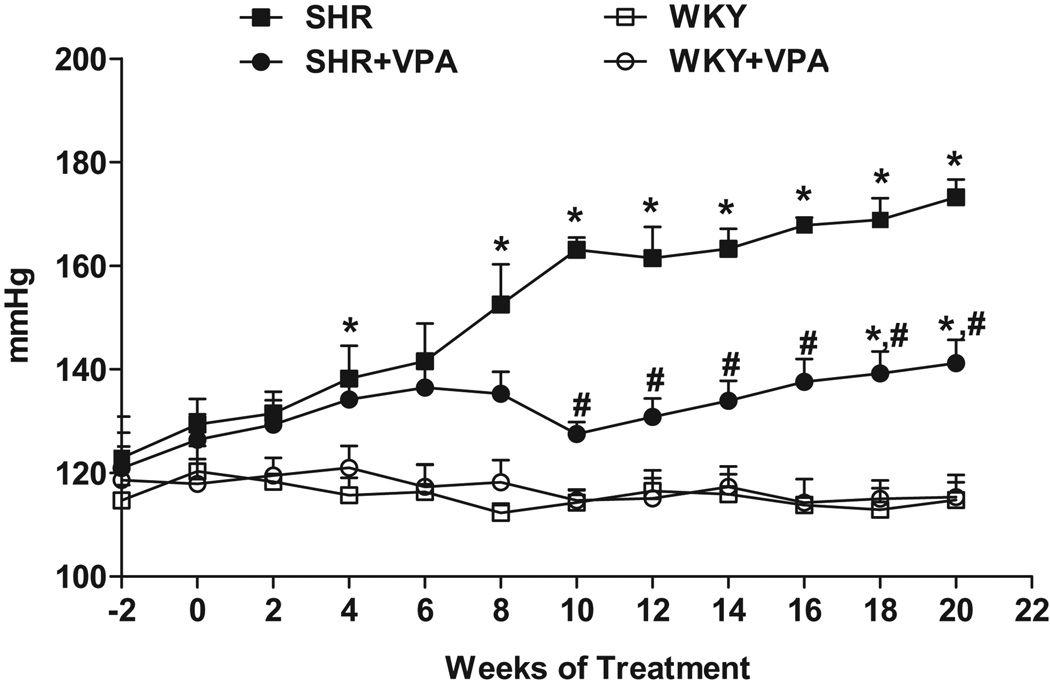

VPA treatment attenuates the blood pressure changes in SHR rats

Blood pressure recordings show that SHR+VPA maintained a lower blood pressure level from the pre-hypertensive to the more advanced hypertensive phases as compared to SHR controls (Figure 1). Following 10 weeks of treatment, SHR control MAP continued to rise while SHR+VPA rats plateaued at a lower pressure (163.1±2.32 vs. 127.5±2.35mmHg, respectively, p<0.05). The MAP of SHR+VPA rose slightly throughout the course of the study, becoming significantly elevated above WKY controls towards the end of the treatment period (141.2±4.5 vs. 114.8±3.41, respectively, p<0.05), but still was significantly lower than the MAP of SHR controls (141.2±4.5 vs. 173.2±3.47, respectively, p<0.05). Mean diastolic and systolic pressures followed the same pattern as the MAP (data not shown), indicating that VPA attenuated all phases of blood pressure in SHR rats. Furthermore, VPA did not have any adverse effects on the health of the animals used in this study.

Figure 1.

Effects of VPA treatment on MAP. VPA attenuated the increase in MAP seen in untreated SHR rats. VPA: valproic acid, MAP: mean arterial pressure. n=7–8 in each group, *P<0.05 vs WKY, #P<0.05 vs SHR.

Another set of animals (n=5 for each SHR and WKY) were treated with HYD, a direct smooth muscle relaxant and vasodilator, to compare their effects against treatment with VPA (Online Data Supplement, Figure S1). SHR+HYD saw a decrease similar to SHR+VPA in MAP as compared to SHR (142.57±4.906 vs. 173.2±3.47). WKY+HYD had no change in MAP. Mean diastolic and systolic followed the same pattern as the MAP in HYD treated rats (data not shown), indicating that HYD similarly attenuated all phases of increased blood pressure seen in SHR rats.

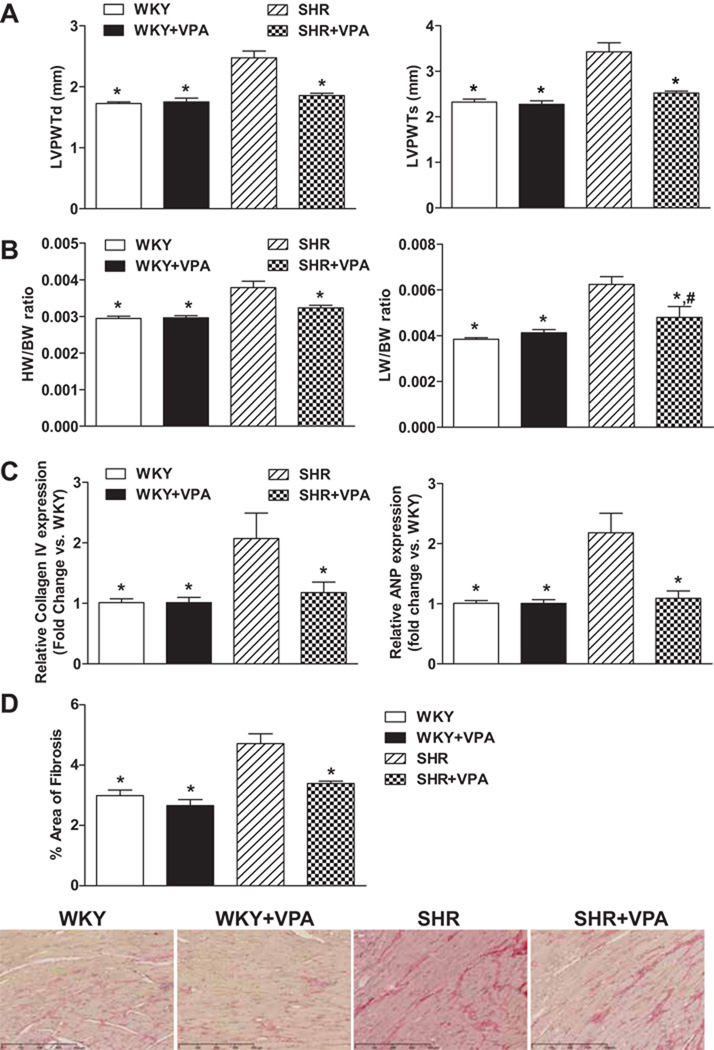

VPA attenuates cardiac hypertrophy in SHR rats

Echocardiographic assessment showed that SHR controls had significantly more concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricular posterior wall (LVPWT) during diastole and systole (Figure 2A) (2.48±0.11 and 3.43±0.2mm, respectively) when compared to WKY controls (1.73±0.02 and 2.32±0.06, respectively). However, SHR+VPA (1.85±0.03, 2.52±0.04mm) rats displayed no change in ventricular thickness as compared to WKY and WKY+VPA (1.75±0.06, 2.28±0.07mm) rats, indicating that VPA had a beneficial effect on preventing the increased LVPWTd/s that is typically observed in SHR rats.

Figure 2.

Effects of VPA treatment on cardiac hypertrophy. VPA attenuated ventricular wall thickness as assessed by echocardiography (2A) during both diastole and systole. VPA also attenuated the HW/BW (indicating reduction in cardiac hypertrophy) and LW/BW (indicating reduction in lung edema due to reduced cardiac function) ratio in SHR rats (2B). SHR rats had increased levels of ANP and Collagen IV mRNA expression which were reduced with VPA treatment (2C). Graphs expressed as fold change versus WKY rats. VPA reduced cardiac fibrosis versus SHR rats as indicated by picrosirius red staining collagen versus total area (2D). Stained slides are representative of typical results for each group (n=3/group). VPA: valproic acid, LVPWT: left ventricular parietal wall thickness, d: diastole, s: systole, HW: heart weight, LW: lung weight, BW: body weight, ANP: atrial natriuretic peptide. n=7–8 in each group, *P<0.05 vs SHR, #P<0.05 vs WKY.

Heart weight (HW)/body weight (BW) and lung weight (LW)/BW ratios are often used to show phenotypic changes due to hypertension such as increased heart mass due to hypertrophy (HW/BW) and increased edema of the lungs (LW/BW) due to cardiac dysfunction and increased systemic circulatory resistance. Treatment with VPA or HYD alone did not have any effects on BW (Figure S2). SHR+VPA normalized both HW/BW and LW/BW indices versus SHR control rats (0.0032 and 0.0048 vs. 0.0039 and 0.0062, respectively, p<0.05) as compared to WKY (0.0029 and 0.0038), reinforcing that VPA reduces cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction (Figure 2B). However, the HW/BW ratio assessed for SHR+HYD did not improve cardiac hypertrophy (Figure S3) as compared to SHR controls (0.0036 vs. 0.0039), indicating that improvements in cardiac hypertrophy due to VPA treatment were not pressure dependent.

VPA reduces hypertrophic response elements in the LV tissue of SHR rats

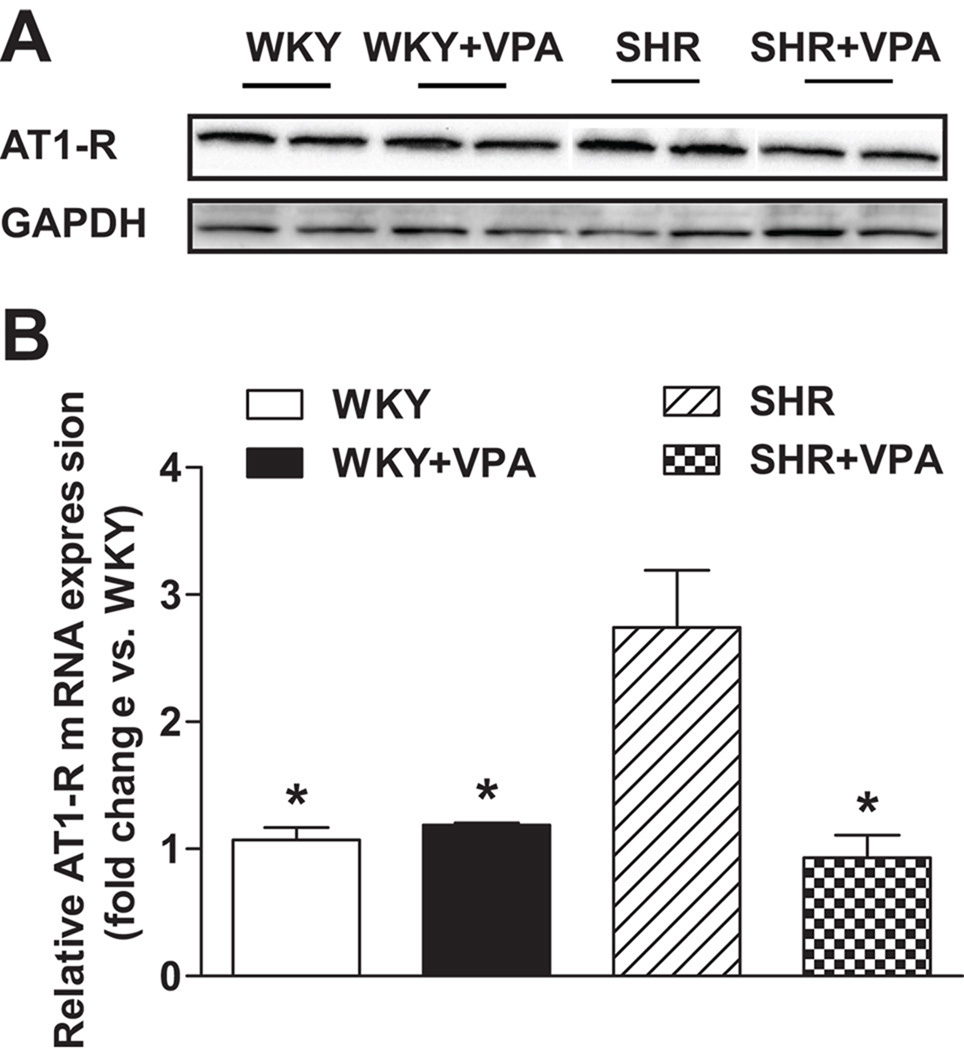

To further demonstrate the effects of VPA on hypertrophy, RT-PCR analysis was undertaken on hypertrophic response genes in the LV. Compared to WKY, untreated SHR rats had elevated levels of collagen IV and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) - two markers of LV remodeling associated with cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 2C), as well as angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1-R). SHR+VPA reduced these levels to that of normotensive WKY controls (p<0.05), indicating HDACi has a positive effect on reducing molecular markers of cardiomyocyte and interstitial growth normally attributed to systemic hypertension. Furthermore, SHR+VPA had reduced % fibrosis staining (Figure 2D) as compared to SHR rats (3.395±0.07 vs 4.713±0.32), signifying a reduction in total fibrosis within the heart following HDACi. The mRNA expression of AT1-R was significantly increased within the LV of SHR rats versus that of normotensive WKY controls (2.7±0.5 fold vs WKY) (Figure 3B), which was fully attenuated in SHR+VPA rats (2.7±0.5 vs. 0.9±0.1 fold vs WKY, respectively) and reconfirmed by western blot of the LV tissues (Figure3A). HYD had no effect on the mRNA expression of either ANP or AT1-R (Figure S4A, B), demonstrating the effect that HDACi has on controlling these locally activated hypertrophic mediators in the LV of SHR rats.

Figure 3.

Effect of VPA on AT1-R mRNA and protein expression. Untreated SHR rats showed higher mRNA (3B) and protein expression (3A) levels of the AT1-R in the LV when compared to WKY controls. SHR+VPA attenuated this increase. Western blot protein expression bands were normalized to GAPDH. VPA: valproic acid, AT1-R: angiotensin II type 1 receptor. n=7–8 in each group, *P<0.05 vs SHR.

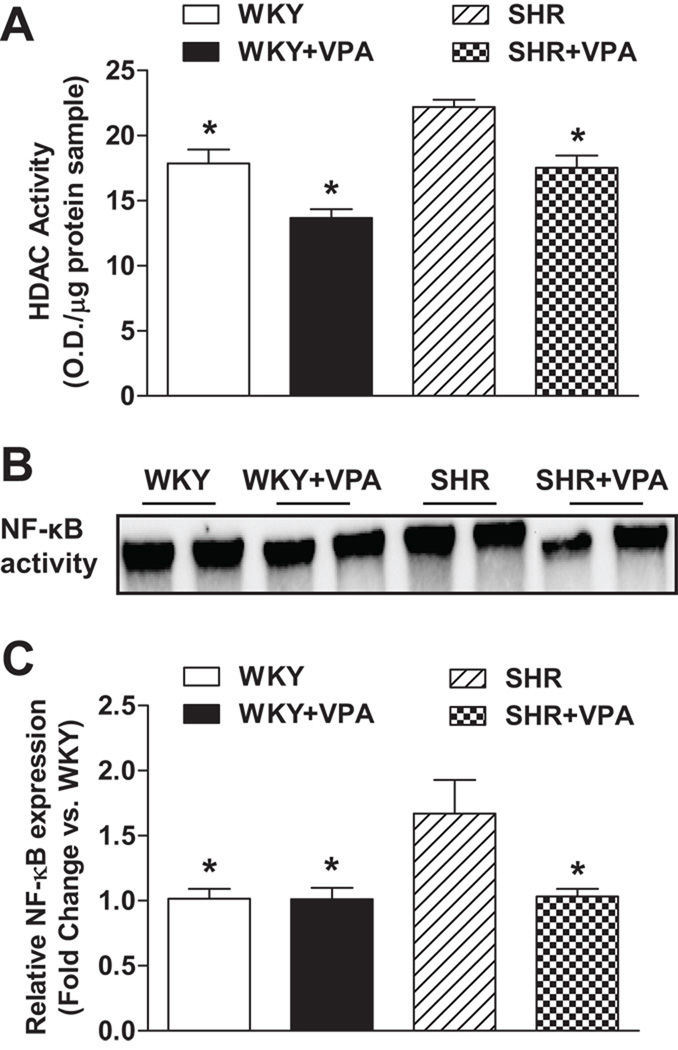

VPA reduces HDAC activity in the LV of treated groups

To assess the effectiveness of VPA on HDAC activity in LV tissue, a colorimetric assay kit was used to analyze differences between the VPA treated and untreated groups (Figure 4A). Global HDAC activity was reduced in untreated WKY versus untreated SHR rats (17.87±1.06 vs. 22.19±0.57 O.D./mg protein sample, respectively, p<0.05). Furthermore, WKY+VPA and SHR+VPA groups both exhibited a lower HDAC activity level (not significant and p<0.05, respectively) as compared to their own strain controls. Conversely, SHR and WKY rats treated with HYD did not have a decrease in HDAC activity when compared with their respective controls (Figure S5).

Figure 4.

Effects of VPA on HDAC activity as assessed through a colorimetric detection assay and NFκB activity and expression via EMSA and real-time RT-PCR, respectively, in the LV. HDAC activity was elevated in both WKY and SHR rats versusWKY+VPA and SHR+VPA rats (4A). Untreated SHR HDAC activity was elevated versus untreated WKY rats. Untreated SHR rats had an increased activity (as determined by EMSA) and mRNA expression of NF-κB which was attenuated in SHR+VPA (4B). VPA: valproic acid, HDAC: histone deacetylase, NF-κB: nuclear factor-kappaB, EMSA: Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay. n=7–8 in each group, *P<0.05 vs SHR.

VPA normalizes inflammatory response in the LV tissue of SHR rats

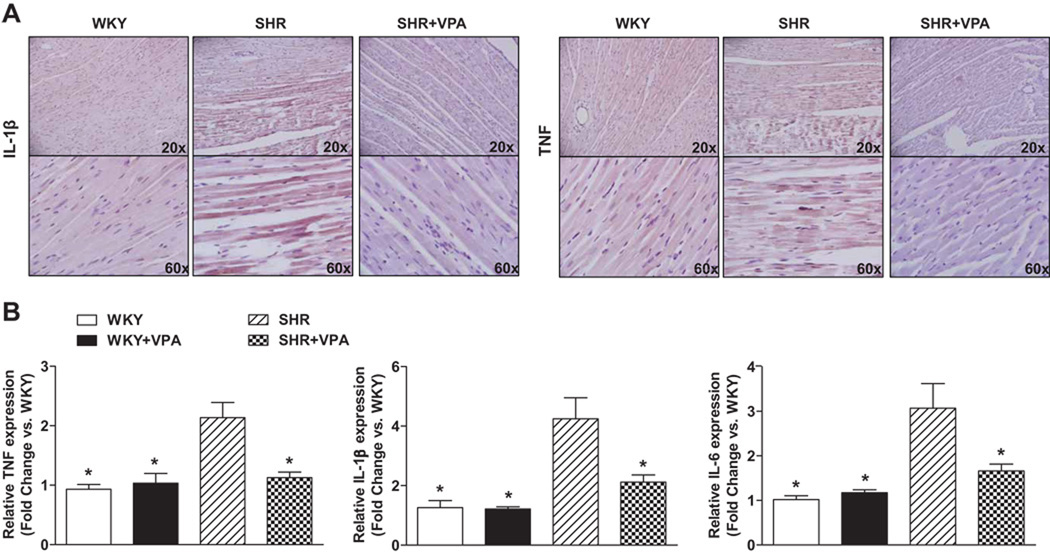

Immunohistochemistry revealed that SHR controls had increased protein expression of TNF and IL-1β in the LV as compared to WKY controls. This protein expression was reduced in SHR+VPA rats (Figure 5A). RT-PCR similarly indicated that SHR controls had increased expression of TNF, IL-1β, IL-6 (Figure 5B) and NFκB (Figure 4C) mRNA in LV tissue when compared to WKY controls. This increase was attenuated in SHR+VPA rats, while WKY+VPA exhibited no change. Furthermore, HYD had no effect on the PIC mRNA expression of TNF or IL-1β (Figure S6A, B). These combined results indicate that VPA treatment reduces and normalizes the inflammatory response observed in SHR rats.

Figure 5.

Effects of VPA treatment on TNF and IL-1β protein and mRNA expression. SHR rats had notably increased protein staining of TNF and IL-1β in the LV when compared to WKY rats as shown through immunohistochemical staining (5A). This staining increase was markedly reduced in SHR+VPA. Images shown represent results observed in preparations from 4 to 6 rats. Untreated SHR rats had increased levels of PIC expression compared to WKY rats (5B). SHR+VPA reduced this increased expression in the LV tissue. VPA: valproic acid, TNF: tumor necrosis factor, IL-1β: interleukin-1beta, IL-6: interleukin-6, PIC: pro-inflammatory cytokines. n=7–8 in each group, *P<0.05 vs SHR.

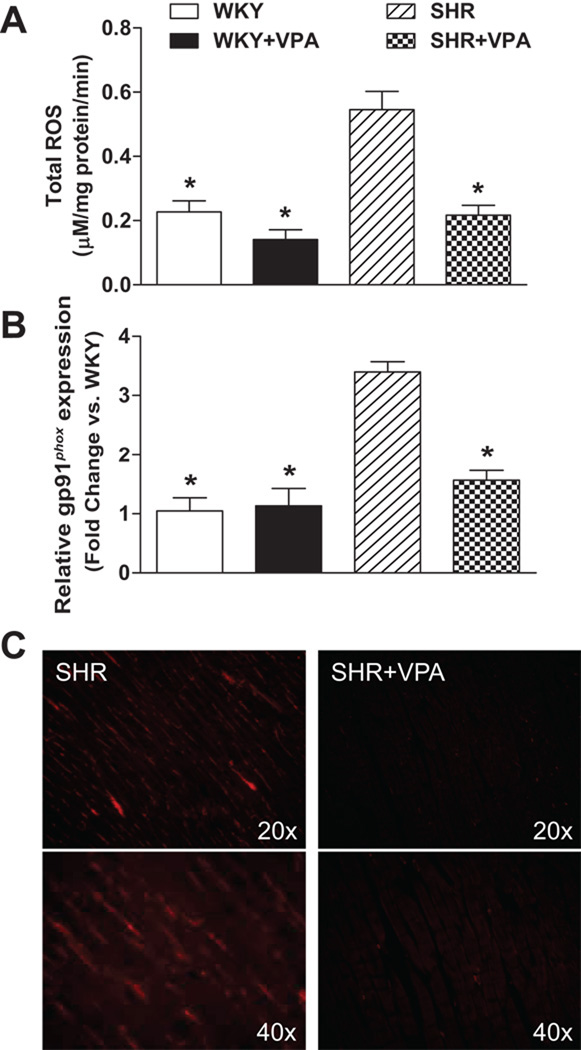

VPA reduces ROS and gp91phox in the LV of SHR rats

As inflammation during hypertensive response is associated with an increase in oxidative stress, both total ROS as assessed by EPR (Figure 6A) and the expression of gp91phox (Figure 6B, 6C) were examined in the LV. Untreated SHR rats experienced a significant increase in ROS when compared to WKY rats (0.54±0.05 vs. 0.22±0.03mM/mg protein/min). SHR+VPA normalized this ROS increase (0.54±0.05 vs. 0.21±0.03mM/mg protein/min). Furthermore, gp91phox, the major catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase and a ROS contributor, was increased in untreated SHR rats versus WKY controls. This was subsequently reduced in SHR+VPA (3.39 vs. 1.56 fold change/WKY), but not SHR+HYD (Figure S6C). The reduction in protein expression was confirmed by immunofluorescence of the LV tissue. These results indicate that treatment of SHR rats with VPA had beneficial effects in reducing oxidative stress in the LV tissue.

Figure 6.

Effects of VPA treatment on tROS and gp91phox in the LV. SHR rats had increased tROS levels as assessed by EPR. These levels were normalized in SHR+VPA (6A). SHR rats also showed increased mRNA (6B) and protein (6C) expression of gp91phox, the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase, in the LV versus WKY rats. This was attenuated in SHR+VPA. Immunofluorescence of LV cardiomyocytes shows increased presence of gp91phox in SHR rats versus SHR+VPA. VPA: valproic acid, ROS: reactive oxygen species, EPR: electron paramagnetic spin resonance. n=7–8 in each group, *P<0.05 vs SHR.

Discussion

The major findings in this study are as follows: 1) HDACs played an important role in hypertensive drive by modulating inflammatory and oxidative stress actions and contributed to hypertrophic and hypertensive responses in SHR rats, 2) HDACi attenuated MAP in SHR rats, 3) HDACi also attenuated LVPWT and HW/BW ratio in SHR rats, demonstrating that HDACi reduces cardiac hypertrophy, possibly in part through modulation of ANP, Collagen IV and AT1-R expression, 4) untreated SHR rats had an increase in inflammatory markers, including TNF and NFκB, as well as an increase in ROS and gp91phox expression, which were decreased through long-term HDACi using VPA, and 5) HDACi reduced AT1-R expression, thereby limiting the role that angiotensin II (Ang II) plays in mediating hypertension. These findings suggest that long-term treatment with VPA reduces hypertension-induced PICs, thereby attenuating hypertrophic and hypertensive responses in SHR rats.

HDACs play an important role in inducing the structural remodeling of chromatin that exposes DNA to transcription factors, ultimately yielding changes in gene expression. Along with HATs, HDACs maintain a relative balance in cellular systems during normal physiology that allows typical function9. However, during diseased conditions, this balance is tilted in favor of HDACs, which can lead to an elevation in inflammatory and immune responses11, 13, 24–27. In this study, we also observed an elevated HDAC activity which was accompanied by increased PIC and oxidative stress gene expression in the hearts of SHR rats.

Cardiac hypertrophy is a well described consequence of systemic hypertension. Studies have shown the role of HDACi on controlling cardiac growth and remodeling28. However, little is known about the holistic role of HDACi on hypertrophy during hypertensive response. As evidence indicates16, 18, 20, 28, 29, pathological cardiac hypertrophy and function rely upon the balanced abundance of α- and β-myosin heavy chain (MHC) protein throughout the heart. During the progression of cardiac hypertrophy, the adult isoform of MHC (α-MHC) undergoes a stressed-trigger switch to the fetal isoform (β-MHC), contributing to cardiac hypertrophy. HDACi blunts MHC isoform switching, therefore preserving ventricular function14, 16, 19. These results are contradictory to earlier experiments showing that class II HDACs block pro-growth genes through interaction with transcription factor myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2)30. More recently though, research has indicated that the pro-hypertrophic class I HDACs, when activated, are more potent and take priority over the anti-hypertrophic class II HDACs28, thus explaining how global HDACi can attenuate cardiac hypertrophy in various animal models16, 29. From these changes, it has been suggested that within the hypertrophied heart, hypertrophic stress signals cause the phosphorylation of HDACs bound to MEF2, causing their disassociation into the cytoplasm. Since these HDACs are not bound to the chromatin structure, their inhibition would have no overt effect on MEF2 transcription, indicating that HDACi has no direct effect on the depression of MEF2 controlled pro-hypertrophic genes and signifying that another mechanism must be in place16.

HDACi using Trichostatin A, an inhibitor of Class I and II HDACs, either induced31 or blunted28 agonist-induced expression of ANP, a hypertrophic growth factor, in cultured neonatal myocytes. The present study also demonstrated that HDACi in SHR rats showed a significant reduction in ANP, suggesting that in SHR rats, ANP possibly plays an important role in attenuating cardiac hypertrophy, and that HDACi silences/blunts this signaling mechanism. Moreover, collagen IV, an indicator of cardiac remodeling, especially within the failing heart32, was increased in SHR rats, but not SHR+VPA rats. Finally, AT1-R, an important component of the RAS which, when acted upon by Ang II in the LV, causes cardiac hypertrophy33, has been shown to be attenuated with VPA treatment29, 34, but the mechanism involved has not been fully investigated. The present study showed significantly reduced AT1-R expression in SHR+VPA rats versus SHR controls, indicating that a possible hypertrophic mechanism more intimately involves AT1-R activation.

There are several well known modulators of pressure-independent cardiac hypertrophy including Ang II and sympathetic neurohormones35. Recently, it was also shown that Ang II-induced cardiac hypertrophy can be prevented using HDACi29. To determine if the current study’s effects on cardiac hypertrophy were pressure-independent or -dependent of HDACi, we looked at the effect of HYD on blood pressure and cardiac hypertrophy, as well as on ANP and AT1-R expression. HYD reduced MAP in SHR rats similar to VPA; however, cardiac hypertrophy was unaffected, including hypertrophic mediators ANP and AT1-R. This indicates a possible pressure-independent mechanism regarding VPA’s effect on cardiac hypertrophy. These results are in agreement with a recent study where NFκB inhibition reduces cardiac hypertrophy in a pressure-independent manner8. This may offer another mechanism whereby HDACi reduces cardiac hypertrophy, for results herein show a decrease in NFκB activity and expression following VPA treatment. Therefore, from these results, not only was cardiac hypertrophy alleviated through long-term VPA treatment, but several possible mechanisms that induce cardiac remodeling were also attenuated.

We and others have recently demonstrated that hypertensive drive is partially controlled through the over-expression of PICs, especially TNF, along with downstream alterations in NFκB, ROS and RAS components, as regulated through AT1-R activation3–5, 36. This study demonstrates that chronic HDACi attenuates PIC response in SHR+VPA rats. Moreover, VPA reduces the presence of ROS and AT1-R, two components implicated in the inflammatory response observed in hypertension. HDACi has been increasingly identified as a possible therapeutic approach towards many inflammatory conditions11, 14, 22, 37, including cardiovascular diseases12. Though this mechanism has not yet been entirely delineated, it is suggested that the use of a HDACi, such as VPA, blocks HDAC actions on protein function outside of its normal action on altering transcription17, 38, as subsets of these families possess the ability to act on non-histone proteins, further complicating their roles in gene modulation39. A recent study showed that HDACi can deactivate Akt, a potential mediator of cardiac hypertrophy and oxidative stress, via dephosphorylation by HDAC-protain phosphatase 1 complexes17. However, other studies have shown that specific sets of Toll-like receptor-inducible genes are targeted by HDACi in macrophages and dendritic cells, and that one of these is through the NFκB pathway24, 25, which concurs with the present study. It underscores the role of HDACi on PIC activation of NFκB, preventing a further, cyclically driven up-regulation of PICs, including TNF, IL-1β and IL-6.

The effect of inflammation on ROS in hypertension has been previously demonstrated3, 40. A number of pro-inflammatory mediators of this increased ROS have been identified, including TNF and IL-6, which, as demonstrated here, are attenuated with HDACi, confirming the roles of HDACs on inflammatory and oxidative stress responses on hypertension in SHR rats. Though the signaling pathway is not entirely clear on how HDACi attenuates ROS in SHR rats, either directly or indirectly through its blockade of PICs and the NFκB pathway, we postulate that by blocking PIC activation, with its subsequent down-regulation of NFκB activity and gp91phox expression, ROS is inhibited.

The interaction between the RAS, PICs and ROS has also been demonstrated by work in our lab5 and others41–43. Presently we show that untreated SHR rats have increased AT1-R expression, an important component of the pro-hypertensive portion of the RAS. HDACi through VPA treatment attenuated this increase concomitant with that of PICs. The pathophysiological mechanism of hypertension intimately involves the action of Ang II, including vasoconstriction, increased aldosterone secretion, increased sympathetic nerve activity, tissue remodeling and increased sodium and water intake, all of which are mediated through AT1-Rs that are distributed throughout most organ systems, including the liver, brain, kidney, heart and blood vessels44. Reports indicate that Ang II is controlled by, and controls, HDAC-induced changes in gene and protein response29, 34. Here we show a possible new mechanism involving the regulation of Ang II responses as directed through the AT1-R. HDACi reduces AT1-R gene expression and receptor density, thereby ameliorating the actions of Ang II. This alteration in AT1-R expression could be either through direct HDACi effects on the receptor’s production and function, or through the effects of HDACi on inflammatory gene response during hypertension. This mechanism must be further investigated in order to determine the full effect of HDACi in attenuating hypertensive response.

In conclusion, the present study’s results show that long-term HDACi through VPA attenuated MAP and cardiac hypertrophy, possibly through modulation of ANP, Collagen IV and AT1-R. HDAC inhibition also attenuated the increased inflammatory response, including TNF and NFκB, as well as the increase in ROS and gp91phox. These findings suggest that HDACi with VPA reduced inflammation, ROS, and AT1-R, thereby attenuating hypertension and its secondary consequences in SHR rats.

Perspectives

We chose to use VPA due to its current use in clinical settings as an anti-seizure and bipolar drug, demonstrating its availability to patients. In our study, VPA was administered long-term without any adverse effects towards the treated animal groups. This outlines the importance of the continuous drug administration necessary for the successful treatment of hypertension and its consequences, including cardiac hypertrophy, systemic inflammation and end organ damage due to ROS. While we cannot rule out the effects of VPA on blood pressure from its GABAergic actions or non-histone protein interactions, we feel confident that this study provides sufficient evidence that the use of HDACi can reduce not only blood pressure, but cardiac hypertrophy and the inflammatory state associated with hypertension. The specific mechanisms involved in HDACi must be studied more closely. However, as the quest to find new therapeutic strategies in hypertensive control is ever pressing, this could present a possible new approach in future treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

These studies were supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Grant HL-80544 (to J. Francis).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Phillips MI, Kagiyama S. Angiotensin II as a pro-inflammatory mediator. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:569–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrario CM, Strawn WB. Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and proinflammatory mediators in cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elks CM, Mariappan N, Haque M, Guggilam A, Majid DS, Francis J. Chronic NF-{kappa}B blockade reduces cytosolic and mitochondrial oxidative stress and attenuates renal injury and hypertension in SHR. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F298–F305. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90628.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mariappan N, Elks CM, Fink B, Francis J. TNF-induced mitochondrial damage: a link between mitochondrial complex I activity and left ventricular dysfunction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:462–470. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sriramula S, Haque M, Majid DS, Francis J. Involvement of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in angiotensin II-mediated effects on salt appetite, hypertension, and cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2008;51:1345–1351. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.102152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kudo H, Kai H, Kajimoto H, Koga M, Takayama N, Mori T, Ikeda A, Yasuoka S, Anegawa T, Mifune H, Kato S, Hirooka Y, Imaizumi T. Exaggerated blood pressure variability superimposed on hypertension aggravates cardiac remodeling in rats via angiotensin II system-mediated chronic inflammation. Hypertension. 2009;54:832–838. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.135905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tokuda K, Kai H, Kuwahara F, Yasukawa H, Tahara N, Kudo H, Takemiya K, Koga M, Yamamoto T, Imaizumi T. Pressure-independent effects of angiotensin II on hypertensive myocardial fibrosis. Hypertension. 2004;43:499–503. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000111831.50834.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta S, Young D, Sen S. Inhibition of NF-kappaB induces regression of cardiac hypertrophy, independent of blood pressure control, in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H20–H29. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00082.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Ruijter AJ, van Gennip AH, Caron HN, Kemp S, van Kuilenburg AB. Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem J. 2003;370:737–749. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsberg EC, Bresnick EH. Histone acetylation beyond promoters: long-range acetylation patterns in the chromatin world. Bioessays. 2001;23:820–830. doi: 10.1002/bies.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halili MA, Andrews MR, Sweet MJ, Fairlie DP. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in inflammatory disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9:309–319. doi: 10.2174/156802609788085250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keslacy S, Tliba O, Baidouri H, Amrani Y. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-inducible inflammatory genes by interferon-gamma is associated with altered nuclear factor-kappaB transactivation and enhanced histone deacetylase activity. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:609–618. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HJ, Rowe M, Ren M, Hong JS, Chen PS, Chuang DM. Histone deacetylase inhibitors exhibit anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects in a rat permanent ischemic model of stroke: multiple mechanisms of action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:892–901. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.120188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bush EW, McKinsey TA. Targeting histone deacetylases for heart failure. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:767–784. doi: 10.1517/14728220902939161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, Fischle W, Verdin E, Greene WC. Duration of nuclear NF-kappaB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Science. 2001;293:1653–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.1062374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong Y, Tannous P, Lu G, Berenji K, Rothermel BA, Olson EN, Hill JA. Suppression of class I and II histone deacetylases blunts pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2006;113:2579–2588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.625467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen CS, Weng SC, Tseng PH, Lin HP. Histone acetylation-independent effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors on Akt through the reshuffling of protein phosphatase 1 complexes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38879–38887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang CL, McKinsey TA, Chang S, Antos CL, Hill JA, Olson EN. Class II histone deacetylases act as signal-responsive repressors of cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 2002;110:479–488. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00861-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee TM, Lin MS, Chang NC. Inhibition of histone deacetylase on ventricular remodeling in infarcted rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H968–H977. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00891.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis FJ, Pillai JB, Gupta M, Gupta MP. Concurrent opposite effects of trichostatin A, an inhibitor of histone deacetylases, on expression of alpha-MHC and cardiac tubulins: implication for gain in cardiac muscle contractility. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1477–H1490. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00789.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki S, Nakata T, Kawasaki S, Hayashi J, Oguro M, Takeda K, Nakagawa M. Chronic central GABAergic stimulation attenuates hypothalamic hyperactivity and development of spontaneous hypertension in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1990;15:706–713. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottlicher M, Minucci S, Zhu P, Kramer OH, Schimpf A, Giavara S, Sleeman JP, Lo Coco F, Nervi C, Pelicci PG, Heinzel T. Valproic acid defines a novel class of HDAC inhibitors inducing differentiation of transformed cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:6969–6978. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kook H, Lepore JJ, Gitler AD, Lu MM, Wing-Man W, Mackay Yung J, Zhou R, Ferrari V, Gruber P, Epstein JA. Cardiac hypertrophy and histone deacetylase-dependent transcriptional repression mediated by the atypical homeodomain protein Hop. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:863–871. doi: 10.1172/JCI19137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aung HT, Schroder K, Himes SR, Brion K, van Zuylen W, Trieu A, Suzuki H, Hayashizaki Y, Hume DA, Sweet MJ, Ravasi T. LPS regulates proinflammatory gene expression in macrophages by altering histone deacetylase expression. FASEB J. 2006;20:1315–1327. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5360com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brogdon JL, Xu Y, Szabo SJ, An S, Buxton F, Cohen D, Huang Q. Histone deacetylase activities are required for innate immune cell control of Th1 but not Th2 effector cell function. Blood. 2007;109:1123–1130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-019711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito K, Charron CE, Adcock IM. Impact of protein acetylation in inflammatory lung diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;116:249–265. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wade PA. Transcriptional control at regulatory checkpoints by histone deacetylases: molecular connections between cancer and chromatin. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:693–698. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antos CL, McKinsey TA, Dreitz M, Hollingsworth LM, Zhang CL, Schreiber K, Rindt H, Gorczynski RJ, Olson EN. Dose-dependent blockade to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28930–28937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kee HJ, Sohn IS, Nam KI, Park JE, Qian YR, Yin Z, Ahn Y, Jeong MH, Bang YJ, Kim N, Kim JK, Kim KK, Epstein JA, Kook H. Inhibition of histone deacetylation blocks cardiac hypertrophy induced by angiotensin II infusion and aortic banding. Circulation. 2006;113:51–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.559724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKinsey TA, Zhang CL, Olson EN. MEF2: a calcium-dependent regulator of cell division, differentiation and death. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:40–47. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuwahara K, Saito Y, Ogawa E, Takahashi N, Nakagawa Y, Naruse Y, Harada M, Hamanaka I, Izumi T, Miyamoto Y, Kishimoto I, Kawakami R, Nakanishi M, Mori N, Nakao K. The neuron-restrictive silencer element-neuron-restrictive silencer factor system regulates basal and endothelin 1-inducible atrial natriuretic peptide gene expression in ventricular myocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2085–2097. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.2085-2097.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimm D, Huber M, Jabusch HC, Shakibaei M, Fredersdorf S, Paul M, Riegger GA, Kromer EP. Extracellular matrix proteins in cardiac fibroblasts derived from rat hearts with chronic pressure overload: effects of beta-receptor blockade. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:487–501. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makino N, Sugano M, Otsuka S, Hata T. Molecular mechanism of angiotensin II type I and type II receptors in cardiac hypertrophy of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1997;30:796–802. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.4.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Y, Yang S. Angiotensin II induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy probably through histone deacetylases. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;219:17–23. doi: 10.1620/tjem.219.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang YM, Ma Y, Zheng JP, Elks C, Sriramula S, Yang ZM, Francis J. Brain nuclear factor-kappa B activation contributes to neurohumoral excitation in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:503–512. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilcox CS, Welch WJ. Oxidative stress: cause or consequence of hypertension. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2001;226:619–620. doi: 10.1177/153537020222600702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adcock IM. HDAC inhibitors as anti-inflammatory agents. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:829–831. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bode KA, Schroder K, Hume DA, Ravasi T, Heeg K, Sweet MJ, Dalpke AH. Histone deacetylase inhibitors decrease Toll-like receptor-mediated activation of proinflammatory gene expression by impairing transcription factor recruitment. Immunology. 2007;122:596–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walkinshaw DR, Tahmasebi S, Bertos NR, Yang XJ. Histone deacetylases as transducers and targets of nuclear signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:1541–1552. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paravicini TM, Touyz RM. Redox signaling in hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arenas IA, Xu Y, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Davidge ST. Angiotensin II-induced MMP-2 release from endothelial cells is mediated by TNF-alpha. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C779–C784. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00398.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brasier AR, Li J, Wimbish KA. Tumor necrosis factor activates angiotensinogen gene expression by the Rel A transactivator. Hypertension. 1996;27:1009–1017. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.4.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sasamura H, Nakazato Y, Hayashida T, Kitamura Y, Hayashi M, Saruta T. Regulation of vascular type 1 angiotensin receptors by cytokines. Hypertension. 1997;30:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen AM, Zhuo J, Mendelsohn FA. Localization and function of angiotensin AT1 receptors. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13 doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00249-6. 31S–38S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.