Abstract

For patients with relapsed Hodgkin Lymphoma, high dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue may improve survival over chemotherapy alone. We assessed outcomes of HDCT-SCT in 37 consecutive adolescent and young adult patients with relapsed HL whose malignancy was categorized based on sensitivity to chemotherapy. We determined whether current outcomes supported the use of HDCT-SCT in all of our patients or just those patients with lower risk characteristics such as chemosensitivity. With a median follow up of 6.5 years, the 2 year overall survival was 89% (95% CI: 62%–97%) for the chemo-sensitive patients (n=21). Whereas for patients with resistant disease (n=16) OS was 53% (95%CI: 25%–74%). Both autologous and allogeneic transplants were well tolerated, with 100 day treatment related mortality under 10%. Our data show encouraging outcomes for patients with chemosensitive relapsed HL who receives HSCT and supports the value of the procedure even when the disease is chemoresistant.

Keywords: Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, Stem Cell Transplant, Salvage Therapy

INTRODUCTION

Overall survival rates for patients diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) approach 90% irrespective of stage at initial diagnosis. (SEER data1996–2003) However, outcomes for patients with primary refractory or relapsed disease after conventional salvage therapy are less favorable, at 20% or less at 5 years.1,2 The current standard of care for most relapsed patients is high dose chemotherapy (HDCT) with autologous stem cell transplant (ABMT), which produces overall survival rates of 30–65% at 5 years.3–14 Randomized controlled studies have validated the benefit of ABMT particularly in adult patients with HL.9,15 It remains controversial, however, whether pediatric and young adult patients with primary refractory or chemo-resistant disease, who are at the highest risk of progression, can truly benefit from transplantation. 16,17

The purpose of this study was to evaluate HDCT-SCT outcomes for pediatric and young adult patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma who were treated at our institution between 1997 and 2008. Prognostic models have defined risk factors that correlate with poorer outcome; conversely patients without these risk factors tend to have good outcomes. Established risk factors include: B symptoms, extra-nodal disease, less than 12 months of sustained remission, and resistance to chemotherapy1,3,5,10,11,13,14,18,19. Our results confirm that patients with chemo-sensitive disease have an excellent outcome after HDCT and SCT, and that benefits, albeit more modest, are obtained even for those with chemo-resistant disease.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

This study is a retrospective review of 37 pediatric and young adult patients (age range: 12–35.1 at time of transplant) who received their initial transplant for Hodgkin’s lymphoma between October of 1997 and October of 2008 at the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy in Houston, Texas. Patients were all < 31 years old at the time of diagnosis. Patient demographics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Characteristic | All n=37 | Autologous n=27 | Allogeneic n=10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Median) | 20.8 (12.0–35.1) | 21.9 (12.0–34.0) | 19.3 (14.9–35.1) |

| Ethnicity, n(%) | |||

| Caucasian | 17(46.0) | 13(48.2) | 4(40.0) |

| Black | 5(13.5) | 3(11.1) | 2(20.0) |

| Hispanic | 11(29.7) | 7(25.9) | 4(40.0) |

| Other | 4(10.8) | 4(14.8) | 0(0.0) |

| Initial Stage, n(%) | |||

| Low | 8(21.6) | 6(22.2) | 2(20.0) |

| Intermediate | 20(54.1) | 15(55.6) | 5(50.0) |

| High | 9(24.3) | 6(22.2) | 3(30.0) |

| Extra lymphatic at relpase, n(%) | |||

| Yes | 17(47.2) | 9(34.6) | 8(80.0) |

| No | 19(52.8) | 17(65.4) | 2(20.0) |

| Chemotherapy response | |||

| Resistant | 16(43.2) | 7(25.9) | 9(90.0) |

| Sensitive | 21(56.8) | 20(74.1) | 1(10.0) |

| Conditioning | |||

| CBV | 13(48.2) | ||

| BEAM | 7(25.9) | ||

| BEAM plus Rituximab | 7(25.9) | ||

| Flu/Campath/TBI | 5(50.0) | ||

| Flu/Mel | 4(40.0) | ||

Definitions

We used the standard definitions of the Children’s Oncology Group 20 (COG): Complete Response (CR): At least 80% reduction in size of tumor or return to normal size with resolution of extra nodal masses. Partial Response (PR): At least 50% reduction in size of tumor but does not qualify as a complete response. Progressive Disease (PD): At least 50% increase in size of any involved node or mass. Stable Disease (SD): less than PR but not PD. Resistant Relapse: less than 50% response to first line salvage therapy. Sensitive Relapse: 50% or greater response to first line salvage chemotherapy. Low Risk Disease: Stages IA, IIA (without bulk disease) Intermediate Risk Disease: Stages IA, IIA (with bulk), Stages IB, IIB, Stage IIIA, IVA. High Risk Disease: Stage IIIB, IVB.

Transplant Regimens

27 patients received high dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue and 10 patients received alllogeneic HLA related or unrelated donor stem cell transplants. One patient (who also had MDS) received an allogeneic transplant after myeloablative conditioning. The other 9 allogeneic transplant patients received submyeloablative conditioning regimens. Table 1 describes the number of patients who received these regimens. 10/27 autologous patients received additional involved field radiation after transplant.

Standard conditioning regimens were used. For recipients of autologous HSCTs the regimens CBV and BEAM were used as follows: (i) CBV: Carmustine 150mg/m2 on days -6,-5,-4; Etoposide 60mg/m2 on day -4 and Cylophophomide 100mg/kg (with MESNA) on day -2. (ii) BEAM: Carmustine 300mg/m2 day -6; Etoposide 200mg/m2 every 12 hours on days -5,-4,-3; Ara-C 100mg/m2 every 12 hours on days -5,-4,-3,-2; Melphalan 140mg/m2 on day -1; with or without Rituximab (anti CD20) 375mg/m2.

For recipients of allogeneic HSCTs the following regimens were used: (i) Flu/TBI/Campath: Fludarabine 30mg/m2 on days -5,-4,-3,-2; Alemtuzamab 10mg on day -5,-4,-3,-2; and TBI 450cGy day -1. (ii) Flu/Mel/ATG: Fludarabine 25mg/m2 on days -6,-5,-4,-3,-2; Melphalan 90mg/m2 on day -2; ATG 30mg/kg on days -3,-2,-1. Indications for allogeneic transplant were chemoresistant disease or presence of MDS, young age (<36 years) and available related or unrelated donor.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics such as median for continuous variables and percentage for categorical variables were provided. Times to overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method, along with the Greenwood pointwise confidence intervals. The log-rank test was performed for comparing probability of survival among groups. For each of the prognostic factors, the univariate Cox model was fitted to calculate the unadjusted hazard ratio. Multivariate Cox analysis started with relevant prognostic factors in the model including graft type, disease staging at diagnosis, extra-nodal disease at relapse, chemo-sensitivity, disease status at time for transplant. The final Cox model included the variables with p-value less than 0.15 or potential confounders. Removed variables were replaced into the model one-by-one to check whether there were any magnitude or p-value changes for the coefficient estimates. Proportional hazards assumptions were also checked. Multiple comparison adjustment was not attempted. Statistical estimate is declared significant if its associated p-value is <0.05.

RESULTS

Overall Response and effect of ethnicity

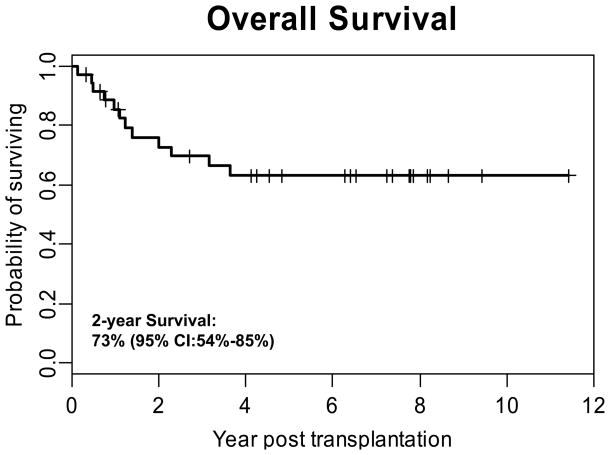

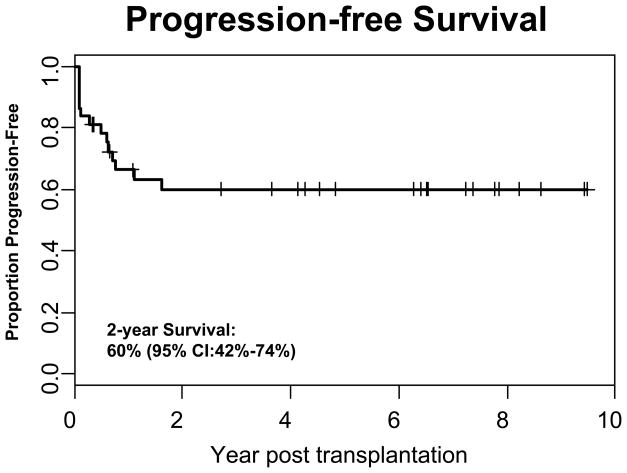

Of the 37 patients who received an HSCT for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, 32 (86%) either sustained or achieved a complete remission, including 26/27 (96.3%) recipients of autologous grafts and 6/10 (60.0%) allogeneic HSCT recipients. The median time of follow-up for all patients is 3.6 years (range 2 months to 11.4 years) and remission was sustained in 76% of the responding patients. For the entire cohort the 2-year OS was 73% (95% CI: 54%–85%) with a PFS of 60% (95% CI: 42%–74%) (Figures 1 and 2). Ethnicity had little impact on OS. Two year OS for whites versus non-whites was 76% (95% CI: 47%–90%) and 71% (95% CI: 43%–87%) respectively, which was not statistically significant (p=0.5287).

Figure 1. Overall Survival of All Patients Who Received a Transplant for Hodgkin’s Lymphoma.

Overall survival of the entire cohort (n=37) is shown demonstrating that the 2-year OS was 73%.

Figure 2. Progression-free Survival of All Patients Who Received a Transplant for Hodgkin’s Lymphoma.

Progression free survival of the entire cohort (n=37) is shown demonstrating a that the 2-year PFS was 60%.

Toxicity

No treatment related mortality was seen in recipients of autologous grafts. For recipients of allogeneic grafts, the treatment related mortality was 1/10 (20%) due to the development of infection and cGvHD in a single patient 9 months after BMT. Three out of the 10 allograft recipients developed mild (grade I, II) and two had severe (III, IV) acute GVHD. Only one patient developed chronic GVHD.

Other late effects included one patient who developed localized melanoma that was successfully treated surgically and one patient who developed monosomy 7 myelodysplastic syndrome 18 months post autologous transplant, coincident with relapse of his Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. This patient is currently disease free 7 years after allogeneic transplant.

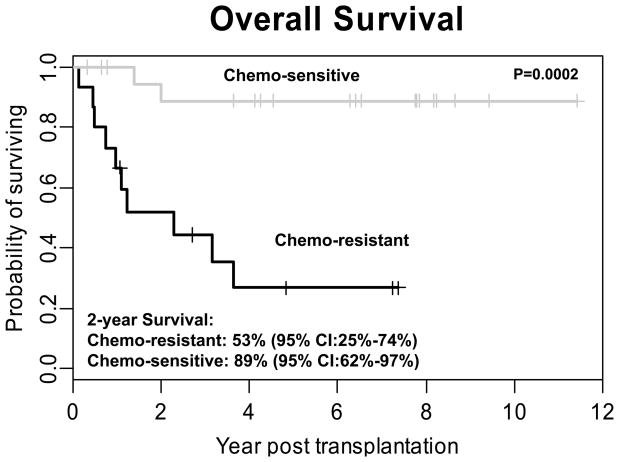

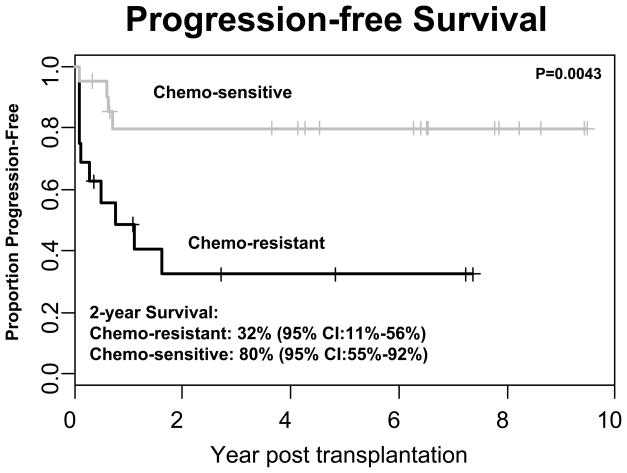

Patients with chemo-sensitive disease had improved outcomes after HSCT

Consistent with other published reports 1,5,10,13,18,19 both disease status at the time of transplant and sensitivity of disease to chemotherapy was highly predictive of outcome. Sixteen (9 allogeneic and 7 autologous) of the 37 patients had chemoresistant disease and 21 (1 allogeneic and 20 autologous) had chemosensitive disease. The one patient with chemosensitive disease who received an allogeneic transplant also had MDS. The 2-Year OS was significantly higher in the chemosensitive group than in the chemoresistant group 89% (95% CI:62%–97%) vs. 53% (95% CI:25%–74%, (p=0.0002)). Similarly, the 2 year PFS was significantly better in the chemosensitive group than in the chemo-resistant group 80% (95% CI:55%–92%) vs, 32% (95% CI:11%–56%) (p=0.004)) (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Overall Survival of Patients with Chemosensitive Versus Chemoresistant Disease.

Patients were stratified based on chemosensitive disease (n=21) and chemoresistant disease (n=16) based on response to initial salvage therapy. A statistically significant improvement in overall survival is seen in patients with chemosensitive disease (89% at 2 years) compared to those with chemoresistant disease (53%; P = 0.0002).

Figure 4. Progression-free Survival of Patients with Chemosensitive Versus Chemoresistant Disease.

A statistically significant improvement in progression free survival is seen in patients (n=21) with chemosensitive disease (80% at 2 years) compared to patients (n =16) with chemoresistant disease (32% at 2 years; P = 0.004).

In the chemosensitive category, 17 out of 21 patients were alive without disease progression after transplant (median follow-up 6.5 years, range 4 months to 11.4 years), whereas, four patients relapsed after autologous HSCT. Of the treatment failures, three died secondary to relapsed disease. The one surviving patient who was a treatment failure received an allogeneic HSCT and is free of disease at > 5 years post second transplant. Seven patients with chemosensitive disease had a sustained remission for 1 year or greater before relapse. None of these seven patients with this additional low risk feature of late relapse had a relapse after autologous HSCT.

Impact of disease status at time of transplant

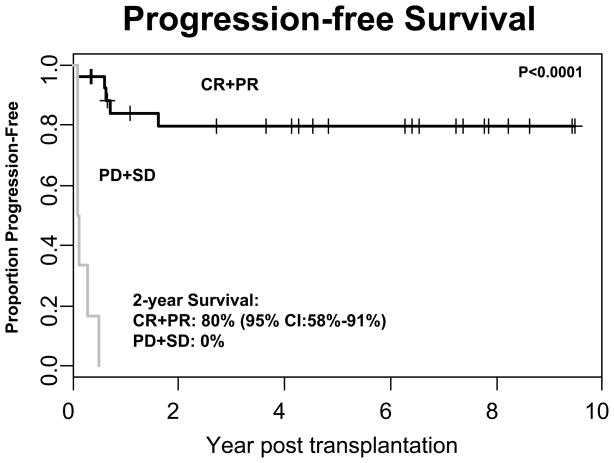

Chemosensitivity was based on response to initial salvage therapy. Hence, disease status at the time of transplant was related to this initial response and was predictive of survival. Initial chemosensitivity and disease status at transplant are not identical for all subjects, however, because some chemotherapy resistant patients subsequently responded to additional treatment prior to transplantation. The 2-year progression-free survival for those with CR or PR at the time of transplant was 80% (95% CI: 58%–91%). However, for patients with PD or SD the PFS was 0%. This was statistically significant (p<0.0001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Progression-free Survival Depending on Disease Status at the Time of Transplant.

Patients were stratified based on their disease status at the time of transplant. Patients who were in complete remission (CR) or partial remission (PR) (n=30) at the time of transplant had a statistically significant improvement in PFS (80% at 2 years) compared to patients (n=7) with either stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD) (0%; P < 0.0001).

Prognostic Factors

On univariate analyses, chemo-resistance, disease status in response to salvage therapy at the time of transplant, and extra-nodal disease at relapse were unfavorable factors significantly affecting overall survival and progression–free survival. We also compared patients with late relapse versus early relapses and found no differences in OS and PFS (p=0.1205 and p=0.1112, respectively, log-rank tests). Multivariate analyses however demonstrated that stable or progressive disease in response to salvage therapy at the time of transplant was significantly associated with poor OS and PFS (P=0.004 and P=0.001, respectively) while controlling for type of transplant, disease stage at the time of transplant and chemo-resistance.

Role of allogeneic HSCT in patients with chemo-resistant disease

In the chemoresistant category, 6/16 (37.5%) (2 autologous and 4 allogeneic) of the patients were alive without disease progression (median follow-up 3.8 years; range 8 months -7.4 years). Ten of the 16 chemoresistant patients relapsed and all of them died with active disease, at a median of 1.0 years (range 2 months- 3.7 years). One patient had an initial response to DLI but then progressed and died of disease. Chemoresistant patients who received allogeneic transplants, however, tended to fare better with a 2 year PFS of 40% (95% CI:10%–70%) compared to the autologous group where the 2 year PFS was 19% (95% CI: 1%–56%). However, this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.6511) likely because of the small patient numbers.

Contribution of consolidative involved field XRT to improved outcome after autologous transplant

Patients were selected for involved field XRT if they had bulky disease before transplant and/or PET positive disease after transplant. We did not observe any difference in outcomes based on the conditioning regimen used in recipients of autologous HSCTs (10/27) who received consolidative involved field XRT after transplant. However, those patients who received XRT after autologous transplant had a 2 year PFS of 88% (95% CI: 39%–98%) compared to a 2 year PFS of 52% (95%CI: 26%–72%) in patients who did not receive XRT after autologous transplant (P=0.1024).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the outcomes of first HSCT in pediatric and young adult patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (HL) who were transplanted at our institution. Most clinical studies evaluating outcomes of salvage therapy for HL have not specifically subdivided the three distinct clinical forms: a childhood form that presents at age <12years, a young adult form that occurs in patients 12–35 years and the older adult form seen in patients >50 years old.21 The historic outcomes for conventional salvage chemotherapy (CT) of HL for all age groups show overall progression free survival at 5 years of about 20% range.2 In this single center study we established that the outcomes of adolescent and young adult patients with HL support the proposition that relapsed patients benefit from either autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Early prospective randomized controlled trials from cooperative groups such as the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the German Hodgkin’s Study Group have demonstrated the superiority of autologous HSCT (ABMT) over chemotherapy for relapsed HL and have established the standard of care for the majority of adult patients with relapsed HL.9,15,22,23 Specifically, the prospective randomized trial from the EBMT showed a 3 year PFS of 41% for patients after ABMT compared to 12% for patients who received conventional chemotherapy alone 9.

We determined whether these adult data would be reflected in our cohort of consecutively treated adolescents and young adults from a single center. Our data supports the excellent outcome of select patients with chemo-sensitive disease, with a 2 year PFS of 80% and 2 year OS of 89%. This is consistent with reported outcomes for adult patients with chemo-sensitive disease which demonstrate a 5yr PFS in the 40–70% range 5,7,18,24,25. Additionally, in our series, we showed that patients with chemosensitive disease who relapsed > 1 year after therapy (n=7) had a 100% PFS after HSCT thus affirming that late relapse predicts excellent prognosis to salvage therapy. Studies in adult patients have also shown that the 2 year survival data for patients receiving HSCT transplant for chemosensitive relapsed HL is predictive, with low numbers of late failures after HSCT.19 However, to truly evaluate late effects such as secondary malignancies, longer follow-up is required. Although this study was not powered to perform a sub group analysis, we also observed improved outcomes among the patients with bulky disease and/or post HSCT PET positive disease who were consolidated with radiation after HSCT suggesting that these results should be evaluated in a larger study.

Whereas the clinical benefit of ABMT in chemo-sensitive patients is clear, it is less evident from the literature how to treat patients (especially adolescent/young adult patients) with chemoresistant disease. While multiple prognostic factors correlate with patient outcome after ABMT including disease stage, extra-nodal disease and anemia, the most consistent and compelling factor remains response to therapy which is either assessed by disease response to salvage therapy or by the number of chemotherapy regimens prior to transplantation. Our data supports the use of HSCT within the chemoresistant group since these patients had a 2 year PFS and OS of 32% and 53% respectively. Although this is a more modest clinical response compared to patients with chemosensitive disease, these results are an improvement from the dismal outcomes observed with CT alone 2. This data therefore suggests that the benefits of the transplant procedure have been maintained even in these high risk patients 1,8,26–28.

Importantly, the use of submyeloablative conditioning regimens and improved supportive therapies, allows both autologous as well as allogeneic HSCTs to be better tolerated with <20% regimen related mortality, an apparent improvement also noted by recent reports in adult patients 29. While we acknowledge our small sample size and although this study was not powered to establish whether allogeneic transplant confers a significant advantage over autologous transplant in terms of PFS in high-risk pediatric/young adult patients, we observed a trend to better outcomes in chemoresistant patients who received an allogeneic HSCT compared to those who received an autologous HSCT. Since prognostic models have now been established it will therefore be important for future studies to establish whether allogeneic transplant is truly beneficial in these high risk adolescent and young adult patients with relapsed HL, as suggested by this study.

In conclusion, our retrospective analysis indicates that most adolescent and young adult patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma can achieve excellent outcomes with high dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant. Physicians treating these patients can be especially optimistic for patients who have an initial cytoreductive response to upfront therapy and who are sensitive to salvage therapy. However, for pediatric and young adult patients who have refractory or chemoresistant disease the outlook especially with autologous HSCT is less satisfactory and novel therapeutic strategies need to be explored either in the context of autologous or allogeneic HSCT.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA125123 and the NIH SPORE Grant P50CA126752.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTREST

The authors report no conflicts of Interests. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCE LIST

- 1.Lohri A, Barnett M, Fairey RN, et al. Outcome of treatment of first relapse of Hodgkin’s disease after primary chemotherapy: identification of risk factors from the British Columbia experience 1970 to 1988. Blood. 1991;77 (10):2292–2298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longo DL, Duffey PL, Young RC, et al. Conventional-dose salvage combination chemotherapy in patients relapsing with Hodgkin’s disease after combination chemotherapy: the low probability for cure. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10 (2):210–218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czyz J, Dziadziuszko R, Knopinska-Postuszuy W, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in advanced Hodgkin’s disease treated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation: a study of 341 patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15 (8):1222–1230. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gribben JG, Linch DC, Singer CR, et al. Successful treatment of refractory Hodgkin’s disease by high-dose combination chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1989;73 (1):340–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Josting A, Franklin J, May M, et al. New Prognostic Score Based on Treatment Outcome of Patients With Relapsed Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Registered in the Database of the German Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20 (1):221–230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazarus HM, Loberiza FR, Zhang MJ, et al. Autotransplants for Hodgkin’s disease in first relapse or second remission: a report from the autologous blood and marrow transplant registry (ABMTR) Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2001;27 (4):387. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martínez C, Arenillas L, López-Guillermo A, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with active Hodgkin’s lymphoma: long-term outcome of 61 patients from a single institution. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2007;48 (10):1968–1975. doi: 10.1080/10428190701573265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moskowitz CH, Nimer SD, Zelenetz AD, et al. A 2-step comprehensive high-dose chemoradiotherapy second-line program for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin disease: analysis by intent to treat and development of a prognostic model. Blood. 2001;97 (3):616–623. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitz N, Pfistner B, Sextro M, et al. Aggressive conventional chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed chemosensitive Hodgkin’s disease: a randomised trial. The Lancet. 2002;359 (9323):2065–2071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08938-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sureda A, Constans M, Iriondo A, et al. Prognostic factors affecting long-term outcome after stem cell transplantation in Hodgkin’s lymphoma autografted after a first relapse. Ann Oncol. 2005;16 (4):625–633. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sureda A, Arranz R, Iriondo A, et al. Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation for Hodgkin’s Disease: Results and Prognostic Factors in 494 Patients From the Grupo Espanol de Linfomas/Transplante Autologo de Medula Osea Spanish Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19 (5):1395–1404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadehra N, Farag S, Bolwell B, et al. Long-term Outcome of Hodgkin Disease Patients Following High-Dose Busulfan, Etoposide, Cyclophosphamide, and Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12 (12):1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brice P, Bouabdallah R, Moreau P, Divine M, André M, Aoudjane M, et al. Prognostic factors for survival after high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with relapsing Hodgkin’s disease: analysis of 280 patients from the French registry. Société Française de Greffe de Moëlle. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1997;20(1):21–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700838. Ref Type: Journal (Full) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horning SJ, Chao NJ, Negrin RS, et al. High-Dose Therapy and Autologous Hematopoietic Progenitor Cell Transplantation for Recurrent or Refractory Hodgkin’s Disease: Analysis of the Stanford University Results and Prognostic Indices. Blood. 1997;89 (3):801–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linch DC, WD, Moir D, et al. Dose intensification with autologous bone-marrow transplantation in relapsed and resistant Hodgkin’s disease: results of a BNLI randomised trial. Lancet. 1993;341 (8852):1051–1054. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92411-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Constans M, Sureda A, Terol MJ, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for primary refractory Hodgkin’s disease: results and clinical variables affecting outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14 (5):745–751. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley MB, Cairo MS. Stem cell transplantation for pediatric lymphoma: past, present and future. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;41 (2):149–158. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Josting A, Engert A, Diehl V, Canellos GP. Prognostic factors and treatment outcome in patients with primary progressive and relapsed Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol. 2002;13 (suppl_1):112–116. doi: 10.1093/annonc/13.s1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navneet S Majhail, Daniel JW, Todd E Defor, et al. Long-Term Results of Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Primary Refractory or Relapsed Hodgkin’s Lymphoma [abstract] Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nachman JB, Sposto R, Herzog P, et al. Randomized Comparison of Low-Dose Involved-Field Radiotherapy and No Radiotherapy for Children With Hodgkin’s Disease Who Achieve a Complete Response to Chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20 (18):3765–3771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pizzo P, Poplack D. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 5. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfreundschuh MG, Rueffer U, Lathan B, et al. Dexa-BEAM in patients with Hodgkin’s disease refractory to multidrug chemotherapy regimens: a trial of the German Hodgkin’s Disease Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12 (3):580–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.3.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byrne BJ, Gockerman JP. Salvage Therapy in Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Oncologist. 2007;12 (2):156–167. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-2-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson JE, Litzow MR, Appelbaum FR, et al. Allogeneic, syngeneic, and autologous marrow transplantation for Hodgkin’s disease: the 21-year Seattle experience. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11 (12):2342–2350. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.12.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chopra R, McMillan AK, Linch DC, et al. The place of high-dose BEAM therapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation in poor-risk Hodgkin’s disease. A single-center eight- year study of 155 patients. Blood. 1993;81 (5):1137–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moskowitz CH, Kewalramani T, Nimer SD, et al. Effectiveness of high dose chemoradiotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with biopsy-proven primary refractory Hodgkin’s disease. British Journal of Haematology. 2004;124 (5):645–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2003.04828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nademanee A, O’Donnell MR, Snyder DS, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with or without total body irradiation followed by autologous bone marrow and/or peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for patients with relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s disease: results in 85 patients with analysis of prognostic factors. Blood. 1995;85 (5):1381–1390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuen AR, Rosenberg SA, Hoppe RT, Halpern JD, Horning SJ. Comparison Between Conventional Salvage Therapy and High-Dose Therapy With Autografting for Recurrent or Refractory Hodgkin’s Disease. Blood. 1997;89 (3):814–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson SP, Sureda A, Canals C, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma: identification of prognostic factors predicting outcome. Haematologica. 2009;94 (2):230–238. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]