Abstract

Objective

To determine if oxygen consumption (VO2) on-kinetics differed between groups of women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and sedentary but otherwise healthy controls.

Design

Exploratory case control study.

Setting

Medical school exercise physiology laboratory.

Participants

Convenience samples of 12 women with SLE and 10 sedentary but otherwise healthy controls.

Intervention

None.

Main Outcome Measurements

VO2 on-kinetics indices including time to steady state, rate constant, mean response time (MRT), transition constant, and oxygen deficit measured during bouts of treadmill walking at intensities of 3-METS and 5-METS.

Results

Time to steady state and oxygen deficit were increased and rate constant was decreased in the women with SLE compared to controls. At the 5-MET energy demand, the transition constant was lower and MRT was longer in the women with SLE than in the controls. For a comparable, relative energy expenditure that was slightly lower than the anaerobic threshold, the transition constant was higher in the controls than in the women with SLE.

Conclusion

VO2 on-kinetics was prolonged in the women with SLE. The prolongation was concomitant with an increase in oxygen deficit and may underlie performance fatigability in women with SLE.

Keywords: Exercise, Oxygen consumption, Rehabilitation

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a collagen vascular disease that affects as many as 1.5 million people in the U.S. alone1. Ninety percent of patients with SLE are women and the disease is most prevalent in the second to fifth decades of life2, 3. Fatigue is among the top three debilitating symptoms of SLE and persists in nearly all patients who have the disease4–8. In patients who have SLE, the severity of fatigue9, 10 and physical disability9 have been strongly associated with decreases in aerobic capacity9–13.

Phenotypes of aerobic capacity include peak VO2, anaerobic threshold, and VO2 on-kinetics14. Each phenotype characterizes a different cardiorespiratory response to physical activity and is regulated by a separate mechanism. For example, peak VO2 is an index of the maximum rate at which the aerobic system can supply energy14, 15. The rate-limiting factor for peak VO2 is thought to be attainment of maximum cardiac output (Qt) but other factors can limit peak VO2 as a result of pathomechanisms14, 15. Severely low peak VO2 has been reported in patients who had SLE compared to healthy controls9, 10, 13 and patients who had anemia or hypertension11. Peak VO2 has been strongly and indirectly associated with self-reports of fatigue severity9, 10 and physical disability9 in patients with SLE.

The second phenotype, anaerobic threshold, is the VO2 corresponding to the onset of anaerobic by-product accumulation during cardiopulmonary exercise testing14, 16, 17. A collage of factors, the confluence of which is not completely understood15, appears to mediate the anaerobic threshold. When aerobic energy output is insufficient for meeting the total energy expenditure, the deficit must be compensated by increased anaerobic glycolysis. High levels of glycolytic activity result in the accumulation of anaerobic by-products in plasma and muscle cells14, 15, 17, which mechanizes work induced fatigue and physical activity intolerance18. Severe decreases in anaerobic threshold have been reported in patients with SLE9–11, 13. In one study, women with SLE approached their anaerobic threshold while walking on a treadmill at energy demands of only 3-METS10. Healthy controls reached their anaerobic threshold at approximately 5-METS. For most healthy adults, energy expenditures of between 3-METS and 5-METS are of moderate intensity19, 20 and easily tolerated.

VO2 on-kinetics reflects the rapidity with which the aerobic system can transition to a state of increased energy output14, 21, 22. From the onset of physical work, total energy output must be sufficient for meeting the energy demand. However, aerobic energy output increases gradually over time (Figure 1), continuing until the energy output of the system reaches a steady state that meets the total demand14, 21, 23. Until the steady state is attained, anaerobic glycolysis compensates for what would otherwise be the energy deficit (oxygen deficit). Because the anaerobic energy contribution is indirectly determined by the rate at which aerobic energy output increases, slowing of VO2 on-kinetics may impair the ability to sustain physical activity. VO2 on-kinetics appears to be regulated by microcirculatory dynamics24–26, and mitochondrial function27–29. Pathological adaptations occurring in the muscle capillary bed of patients with SLE could impair microvascular reactivity and oxygen diffusion30–34. However, a report on VO2 on- kinetics in patents with SLE was not found.

Figure 1.

Oxygen consumption during continuous exercise. t0 is the onset of exercise and t1 is the time taken to reach a steady state or an asymptote and (t6) is 6-minute test endpoint. Area between Line A and the X-axis the resting VO2 and Line B represents the energy demand of the activity being performed. The area above the trajectory line and under Line B is the oxygen deficit. VO2 is the amplitude of change in oxygen consumption at the 6-minute test endpoint.

The purpose of this study was to provide an initial characterization of VO2 on-kinetics during treadmill walking in women with SLE. VO2 on-kinetics was examined at what are typically moderate intensities for most healthy adults in who cardiorespiratory function is uncompromised. The hypothesis that VO2 on-kinetics may be diminished in women with SLE was tested. The main analysis compared five indices of VO2 on-kinetics between a group of women with SLE and a group of sedentary but otherwise healthy controls.

METHODS

Subjects

Twelve sedentary women who had SLE and 10 sedentary but otherwise healthy women participated in this study (Table 1). Ages ranged from 27 to 57 years in the subjects with SLE and from 30 to 43 years in the controls. Subjects denied participating in any physical activity that caused them to perspire for 10 minutes or longer, once or more per week, in the six months prior to participation. Subjects with SLE met at least four of the 11 American College of Rheumatology 1982 Revised Criteria for the Classification of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus35. The women with SLE had Systemic Lupus Activity Measure scores indicating their disease activity had been negligible to mild with no flares for the previous 30 days. Six of the women with SLE were on maintenance doses of prednisone (mean dose = 9.2 ± 3.8 mg/day, n=6); two were on five mg/day, three were on 10 mg/day, and one was on 15 mg/day. None of the women with SLE had comorbidities known to impair treadmill walking. Exclusionary conditions included circulatory, chronic or restrictive pulmonary, renal, neurological, or musculoskeletal diseases, which would adversely affect cardiorespiratory function. Those with severe anemia (plasma [HB] < 12 g/dl), fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome were also excluded. None of the subjects was taking medications known to limit or enhance exercise tolerance or aerobic capacity.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Maximum Treadmill Exercise Test Responses

| SLE |

Control |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.3 ± 09 .4 | 39.1 ± 04.0 |

| Height (cm) | 160.80 ± 06.5 | 165.60 ± 08.0 |

| Weight (kg) | 70.03 ± 09.51 | 72.50 ± 15.73 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/meter2) | 27.42 ± 05.65 | 26.48 ± 05.44 |

| Peak Respiratory Exchange Ratio | 1.19 ± 0.07 | 1.29 ± 0.07 |

| Attained Peak Heart Rate (beats/min) | 163 ± 17 | 168 ± 29 |

| Predicted Peak Heart Rate (beats/min) | 182 ± 10 | 181 ± 04 |

| % Predicted Max Heart Rate | 90.2 ± 0.09 | 91.0 ± 0.17 |

| Peak VO2 (ml/kg/min) | 20.1 ± 04.7* | 28.9 ± 05.1 |

| Anaerobic Threshold (ml/kg/min) | 12.9 ± 02.9** | 17.9 ± 03.1 |

Data are means ± one standard deviation unit. BMI = body mass index, RER = respiratory exchange ratio,

Significantly different from controls; p=0.0001; 95% CI: 03.7 to 15.3 ml/kg/min,

Significantly different from controls; p=0.0001; 95% CI: 01.5 to 09.3 ml/kg/min

This protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional, human subjects review board prior to its beginning. Informed consent was obtained from each subject prior to participation in accordance with institutional policies and the Declaration of Helsinki36.

Apparatus and Formulae

Exercise tests were completed on a Trackmaster motorized treadmilla and pulmonary gas exchange measurements were made using a Medgraphics Cardio 2, breath-by-breath cardiopulmonary exercise testing systema. The system was calibrated before each test. Anaerobic threshold was determined by the V-slope method37. Peak heart rate was determined electronically from an electrocardiogram by multiplying the six-second cardiac cycle rate by 10. Peak cardiac output (Qt) was measured by the exponential rise CO2 rebreathing technique38 applied at peak exercise. Peak arteriovenous oxygen difference (a-vO2) was calculated by dividing peak VO2 by peak Qt.

VO2 on-kinetics was characterized using the monoexponential model developed by Whipp23. VO2 was plotted on time during continuous work rate tests (Figure 1). The algorithm, VO2(t) = (ΔVO2 + VO2rest)(1−e−tk) was then applied. In this model ΔVO2 is the amplitude of increase in oxygen consumption at the sixth minute of exercise, t is time, and K is the rate constant. Attainment of a steady state was determined by the least squares method and confirmed by absence of a statistically significant increase in VO2 between the third and sixth minutes of the exercise bout. Pearson product moment correlation coefficients (r) were calculated to quantify goodness of fit of the VO2 kinetics algorithm. Goodness of fit was determined by the relationship between the iterations of VO2 plotted on time generated by the algorithm and those actually measured. Significant correlation coefficients indicated high goodness of fit for the VO2 on-kinetics model (Table 2). Eighty nine percent and 91% of the variances in VO2 were attributed to the time domain in the women with SLE and controls respectively. Oxygen deficit was calculated as [6 minutes times steady state VO2] minus the area below the VO2-time curve (Figure 1). The overall VO2 on-kinetics rate was quantified by a transition constant, calculated as the quotient of VO2 and MRT 39, where MRT is the mean response time.

Table 2.

Goodness of FIT for the VO2 Kinetics Model

| Median | Mode | Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lupus | 0.966 | 0.970 | 0.945 | 0.063 | 0.688 | 0.991 |

| Controls | 0.960 | 0.973 | 0.960 | 0.031 | 0.866 | 0.981 |

Pearson product moment correlation coefficients for relationships among VO2-time iterations calculated from the model algorithm and those actually measured during the steady state tests. Data include both 3-MET and 5-MET energy demands for each group. SD is one standard deviation, Min is the lowest r-value, and Max is the highest r-value.

Procedure

Subjects first rested quietly in the supine position for at least 10 minutes. Subjects then completed a maximum treadmill test according to the modified Bruce protocol40. The targeted stopping point for this test was the subject’s indication that she could not continue exercising despite strong encouragement from the testing staff. Pulmonary gas exchange and heart rate were measured throughout the test. Cardiac output was measured at peak exercise.

Forty eight to 164 hours after completing the maximum treadmill tests, subjects completed two randomly ordered, continuous work rate tests. A simple Latin square randomization method ensured equal ordering. These tests consisted of six minutes of sustained treadmill walking at 3-MET and 5-MET energy demands. The intensity of 3-METs corresponded to treadmill walking at a speed of 2.0 mph and an inclination of 1.5% grade19, 20. The intensity of 5-METs corresponded to a speed of 2.0 mph and an inclination of 9.0% grade19, 20. Subjects rested quietly for 10 minutes prior to the first test in the order. A recovery period separated the first test in the order from the second test. During recovery, subjects rested in the supine position for 20 minutes or longer, until heart rate and VO2 returned to resting levels. VO2 was measured continuously throughout these work bouts and VO2 on-kinetics was determined from these measurements.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using the SAS, version 9.1, statistical analysis systemb. One and two-way ANOVA and ANCOVA were used for testing for intergroup, test, and interaction differences. The least squares means procedure was applied following the finding of a significant interaction in the two-way analyses. The general assumptions underlying these procedures are that ratio or interval data is being analyzed and that additional observations beyond our small sample (N=22) would trend toward a normal distribution of the mean according to the Central Limit Theorem41. Dependent variables measured during the maximum treadmill test were secondary outcome measures and included were peak VO2, anaerobic threshold, Qt, a-vO2, respiratory exchange ratio and heart rate. These data were assessed for significant group differences by one-way statistical analyses. The main outcome variables for this study were the indices of VO2 on-kinetics including transition constant, time to steady state, rate constant, MRT, and oxygen deficit. These data were acquired during the submaximal, continuous work rate tests and assessed for significant group and test differences by two-way analyses. Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05. Reported means are adjusted for covariance when appropriate. Otherwise, data are reported as simple means ± one standard deviation.

RESULTS

Despite the difference in the age ranges, mean age and other group demographics were similar for the women with SLE and controls (Table 1). Gas exchange data obtained from the maximum treadmill tests are also provided in Table 1. Both groups attained a peak RER of greater than 1.15 and a peak heart rate of at least 90% of the age predicted peak heart rate, where predicted peak heart rate=220 bpm − 1 bpm per year of age. These criteria are accepted indicators that VO2 approached a physiologically maximal level at volitional exhaustion19, 20, 42 and that tests were not stopped early due to motivational factors.

Age was not a significant covariate in the group comparisons of peak VO2, anaerobic threshold, Qt, a-vO2, RER, or any of the measures of VO2 on-kinetics. ANOVA indicated that peak VO2 and anaerobic threshold were 30.4% and 27.9% lower in the women with SLE than in the controls, respectively (Table 1). Measurements of Qt were available in eight patients with SLE (14.0±0.31L/min) and eight controls (13.8±02.8 L/min). Qt was not significantly different between these subgroups. However, peak a-vO2 was 21% lower (p<0.029 CI: 11.3 to 30%) in the women with SLE (10.5±02.4 vol%) than in the controls (13.3±02.1 vol%).

A significant difference in ΔVO2 was not observed between the women with SLE and the controls (Table 3). ANOVA indicated that ΔVO2 was significantly higher (p<0.002, 95% CI: 180 to 252 ml/min) for the 5-MET energy demand than for the 3-MET energy demand. A significant difference in ΔVO2 was not observed between the third and sixth minutes of exercise in either group or between the 3-MET or 5-MET tests. ΔVO2 covaried significantly with rate constant (p<0.002), MRT (p<0.015) and oxygen deficit (p<0.001). ΔVO2 did not covary with transition constant, or time to steady state.

Table 3.

Changes in ΔVO2 for the 3-MET and 5-MET Energy Demands

| 3-MET |

5-MET |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lupus | Control | Lupus | Control | |

| ΔVO2 (ml/min)* | 599 ± 293 | 540 ± 144 | 766 ± 261 | 817 ± 225 |

| ΔVO2(6–3) (ml/min) | −06.3 ± 66.7 | −03.8 ± 56.4 | 05.8± 80.0 | −05.6 ± 58.2 |

Data are means ± one standard deviation. ΔVO2 is the change in oxygen consumption above rest at minute six of exercise, and ΔVO2(6–3) is the difference in VO2 above rest between the third and sixth minutes of exercise.

Significantly higher for 5-METS than for 3-METS (statistical main effect, p=0.0016, 95% CI: 180 to 252 ml/min)

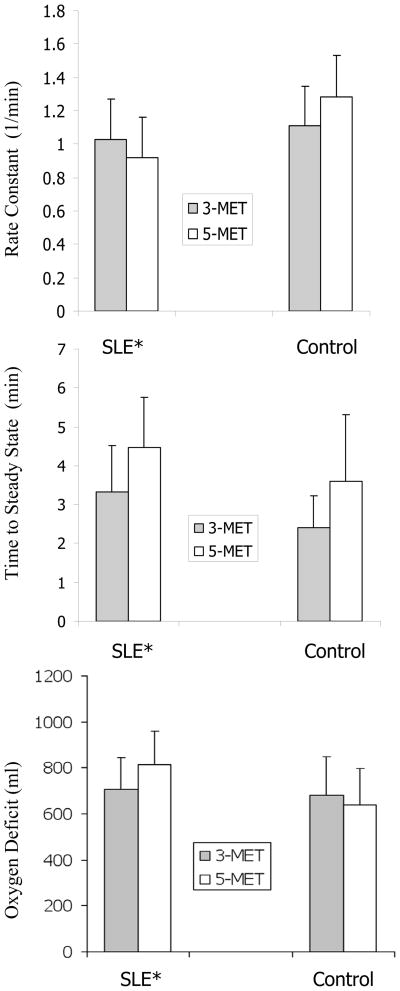

Time to steady state, rate constant, and oxygen deficit responses are depicted in Figure 2. ANOVA indicated that time to steady state was significantly longer (p=0.0027; CI: 0.13 to 2.11 min) for the 5-MET test than for the 3-MET test. ANCOVA and ANOVA main effects indicated that rate constant was lower (p<0.005; 95% CI: 0.00 to 0.42 min−1), time to steady state longer (p<0.016; 95% CI: −0.08 to 1.86 min), and oxygen deficit higher (p<0.028; 95% CI: −32 to 216 ml) in the women with SLE than in the controls.

Figure 2.

Time to steady state, rate constant, and oxygen deficit in women with SLE and controls. Error bars equal one standard deviation unit. * Significantly different main effects for women with SLE than for controls (p<0.005 rate constant, p<0.016 time to steady state, p<0.028 oxygen deficit)

Figure 3 describes the group and test differences in transition constant and MRT. ANOVA indicated that for the 5-MET test, the transition constant was lower (p<0.004; 95% CI: 0.393 to 7.647 ml/min/sec) and the mean response time longer (p<0.0170; 95% CI: −2.701 to 34.720 sec) in the women with SLE than in the controls(Figure 3). In the women with SLE, the transition constant did not increase from the 3-MET test to the 5-MET test. However ANCOVA indicated that MRT was significantly (p<0.0237; 95% CI: −02 to 32 sec) longer for the 5-MET test than for the 3-MET test in the women with SLE. In controls the transition constant significantly (p<0.0136; 95% CI: 0.094 to 6.08 ml/min/sec) increased from the 3-MET test to the 5-MET test, whereas test differences in their MRT were not observed.

Figure 3.

Transition constant and mean response time in women with SLE. Error bars are one standard deviation unit. * significantly higher than 3-METS (p<0.004), + significantly higher than 3-METS in the women with SLE, **significantly higher than 3 METS (p<0.017).

In the women with SLE, VO2 at six minutes of walking at 3-METS was 88.5 ± 25.9% of the anaerobic threshold value. In the controls, VO2 at six minutes of walking at 5-METS was 87.3 ± 23.8% of the anaerobic threshold value. Although these percentages of anaerobic threshold VO2 were nearly identical between the groups, the transition constant was significantly (p<0.014; 95% CI: −0.20 to 7.02 ml/min/sec) higher in the controls than in the women with SLE (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

In the women with SLE, VO2 on-kinetics was prolonged in response to what are typically moderate and easily tolerated walking intensities for most healthy individuals. The maximum rate for VO2 on-kinetics was attained at the 3-MET energy demand in the women with SLE, whereas a significant increase in the rate occurred between the 3-MET and 5-MET energy demands in the controls. Moreover, the VO2 on-kinetics rate was lower in the women with SLE than in the controls, even at comparable levels of energy expenditure relative to and slightly below the groups’ anaerobic thresholds. Results of this study were in agreement with the hypothesis that VO2 on-kinetics may be reduced in women with SLE, particularly during treadmill walking at work rates that are of moderate intensity for most healthy subjects.

In the control group, peak VO2 was similar to age predicted, population normative values as determined by the well-established algorithm of Bruce43, 44. Anaerobic threshold occurred on average at approximately 62% of peak VO2, a level typical of healthy adults45, 46. In addition, the MRT was similar to previous reports in healthy, sedentary adults47–49. These findings suggest that, in the controls, the aerobic response was indicative of those expected for sedentary but otherwise healthy women in the general population.

The magnitude of the observed decreases in peak VO2, anaerobic threshold, and VO2 on-kinetics in the women with SLE in this study were similar to those previously reported in patients with chronic illnesses such as congestive heart failure50, 51, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease52 and highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection39, 53, 54. Peak VO2 in the women with SLE was also far below values reported after 10 days of bed rest in healthy women of similar ages55. In the women with SLE, peak VO2 was 32.0 ± 13.3% lower than levels expected for healthy, sedentary women of similar ages, as determined by the well established algorithm of Bruce43, 44. The decreases in peak VO29, 11, 13, 56, and anaerobic threshold11, 13, 53, 56 in the women with SLE in this study were also similar to previous reports on patients with SLE. All combined, the number of observations in these reports was substantial. No previous reports were found in which peak VO2 or anaerobic threshold in patients with SLE were similar to or higher than healthy controls’. In concert, the totality of observations suggest that the trends observed in this and the previous studies may reflect activity-induced, metabolic responses that are characteristic of the population of patients with SLE in general. However, previous information is lacking regarding VO2 on-kinetics in patients with SLE.

The initial component of VO2 on-kinetics is a fast response in which VO2 increases rapidly towards the steady state. Proposed regulators57 of the fast component include central circulatory oxygen delivery58–60, capillary blood flow dynamics24–26, and dynamics of muscle fiber recruitment24, 61. Mitochondrial inertia and respiratory chain inhibition have also been suggested as fast component regulators27–29, 27, 28, 62. Group similarity in peak Qt suggested that central circulatory oxygen delivery was not impaired in these women with SLE. Conversely, the large reduction in peak a-vO2 suggested that aerobic metabolism could have been limited by restricted muscle oxygen extraction. Microvascular adaptations have been observed in skeletal muscle samples obtained from individuals who had SLE30–34. These adaptations could impair muscle oxygen extraction and slow the fast component by diminishing the microvascular reserve and impeding oxygen influx diffusion.

A plateau in the VO2-time plot follows the fast component, indicating that an aerobic steady state has been achieved with the total energy demand14, 21, 23. However, the plateau is often replaced by a slower rise of VO2 that delays the onset of the steady state when the work being performed is of severe intensity63. This slow component may be less likely to occur during treadmill exercise than during cycling64. Some29, 65–67 but not all68 studies have suggested that progressive recruitment of Type-II muscle fibers may mediate the slow component. Predominance of Type-I muscle fibers and selective Type-II muscle fiber atrophy have been observed in muscle samples obtained from individuals with SLE69. This adaptation is not completely understood but could possibly attenuate a slow component transition.

VO2 on-kinetics is slower in untrained individuals than in those who are more physically fit70, 71. Aerobic exercise training may improve VO2 on-kinetics72–74. While aerobic exercise training has been reported to increase peak VO2 and anaerobic threshold in patients with SLE12, 75, further research is needed to determine whether exercise training can improve VO2 on-kinetics in patients with SLE.

Study Limitations

Half of the women with SLE in the current study were maintained on non-fluorinated, orally administered prednisone with doses well below 40 mg/day. Drug induced myopathy is one possible side effect of this medication, particularly when the agent is fluorinated or dosages exceed 40 mg/day76. Orally administered prednisone dosages, similar to those used by patients in the current study, have been shown to neither decrease mitochondrial enzyme concentrations77 nor reduce peak VO278. However, the effect of prednisone on VO2 on-kinetics is yet unknown.

Physically inactive lifestyle was an inclusion criterion of this study. However, routine physical inactivity was determined subjectively and by a single question. Because patients with SLE may be more fatigable, physical activity levels could have been slightly lower in the women with SLE than in the controls. Bostrom and associates reported that peak VO2 was not related to daily physical activity levels in women with SLE56. However, it remains unknown as to whether VO2 on-kinetics is associated with daily physical activity in this patient population.

The rate of VO2 on-kinetics may be increased by prior, strenuous exercise79–81. Equal randomization of test order and a return of VO2 to baseline levels between the tests were used in an attempt to minimize this effect. An equal number of subjects completed each of the testing orders in both of the groups. However, the 5-MET energy demand was above the anaerobic threshold only in the women with SLE so it may have been more strenuous for them than for controls. Bias in the distribution of this effect may have been introduced despite equality in the test order. If so, the rate of rise in VO2 during the 3-MET exercise bout could have been slightly increased and the time taken to achieve the steady state slightly decreased, by prior exercise, in the women with SLE who completed the 5-MET test before completing the 3-MET test.

Menstrual cycle phase and use of oral contraceptives were not controlled in this study. Dean and associates reported that in healthy women, menstrual phase had no effect on peak VO2 or lactate threshold82. Lebrun et al83 reported a small decrease in peak VO2 of 4.7% from the follicular to the mid-luteal phase in a group of healthy women using oral contraceptives. However, a slight increase of 1.4% occurred across these phases in a placebo control group. Similar effects would account for a variance of no greater than -20% to +06% of one standard deviation from the mean peak VO2 in the women with SLE (−0.95 to +0.28 ml/kg/min) and −27% to +08% in the controls (−1.36 to +0.40 ml/kg/min). Thus the potential bias introduced by variance in the menstrual phase and uncontrolled use of oral contraceptives appears to be minimal.

For this study, a convenience sample of patients with SLE was recruited in which volunteers were identified and selected from patient records. Due to the non-randomized selection of the small sample of subjects, selection bias could have affected the interpretation of the results. Therefore, even though there were response similarities among these subjects with SLE and numerous other reports, generalizations to the overall population of subjects with SLE must be made with due caution.

CONCLUSIONS

VO2 on-kinetics during treadmill walking was slower in the women with SLE than in sedentary but otherwise healthy controls. Oxygen deficit was higher in the women with SLE than the controls. It is possible that impaired VO2 on-kinetics may contribute to performance fatigability in patients with SLE.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, (grant no. 1R03HD39775).

List of Abbreviations

- ANCOVA

analysis of covariance

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- METS

metabolic equivalents

- MRT

mean response time

- RER

respiratory exchange ratio

- VO2

oxygen consumption

Footnotes

Medical Graphics Corporation. 350 Oak Grove Parkway, St. Paul, MN 55127.

SAS Institute Inc. 100 SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC 27513-2414

No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on the authors or on any organization with which the authors are associated.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pisetsky D, Buyon J, Manzi S. Systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Klippel H, Crofford L, Stone J, Weyand C, editors. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. 12. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rus V, Hajeer A, Hochberg M. Systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Silman A, Hochberg M, editors. Epidemiology of the Rheumatic Disease. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ad Hoc Committee on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Response Criteria for Fatigue AH. Measurement of fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1348–57. doi: 10.1002/art.23113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir J, Steinberg AD. A study of fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:1450–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:1121–3. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahita RG. Systemic lupus erythematosus. 4. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tench CM, McCurdie I, White PD, D'Cruz DP. The prevalence and associations of fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:1249–54. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tench C, Bentley D, Vleck V, McCurdie I, White P, D'Cruz D. Aerobic fitness, fatigue, and physical disability in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(3):474–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keyser RE, Rus V, Cade WT, Kalappa N, Flores RH, Handwerger BS. Evidence for aerobic insufficiency in women with systemic Lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:16–22. doi: 10.1002/art.10926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakauchi M, Matsumura T, Yamaoka T, Koami T, Shibata M, Nakamura M, et al. Reduced muscle uptake of oxygen during exercise in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1483–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, White PD, D'Cruz DP. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:1050–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forte S, Carlone S, Vaccaro F, Onorati P, Manfredi F, Serra P, et al. Pulmonary gas exchange and exercise capacity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2591–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY, Stringer WW, Whipp BJ. Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation. 4. Philadelphia: Lipincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks G, Fahey T, Baldwin K. Exercise Physiology: Human Bioenergetics and Its Applications. boston: Mcgraw Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasserman K. Determinants and detection of anaerobic threshold and consequences of exercise above it. Circulation. 1987;76:VI29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasserman K, Koike A. Is the anaerobic threshold truly anaerobic? Chest. 1992;101:211S–8S. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.5_supplement.211s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris C, Adams KJ, Keith N. Exercise Physiology. In: Kaminski L, Bonheim KA, Garbor CE, Glass SC, Hamm LF, Kohl HW, et al., editors. ACSM's Resource Manual for Guidelines For ExerciseTesting and Prescription. 5. Philadelphia: Lipincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 45–78. [Google Scholar]

- 19.ACSM. ACSM's Guidelines For Exercsie Testing and Prescription. 7. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkiins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson W, Gordon N, Pescatello L, editors. ACSM'S Guidelines or Exercise Testing and Prescription. 8. Philadelphia: Wolters kluwer / Lipincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whipp BJ. Dynamics of pulmonary gas exchange. Circulation. 1987;76:VI18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whipp BJ, Ward SA, Lamarra N, Davis JA, Wasserman K. Parameters of ventilatory and gas exchange dynamics during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1982;52:1506–13. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.6.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whipp B. Rate constant for the kinetics of oxygen uptake during light exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1971;30:261–3. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.30.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barstow TJ, Jones AM, Nguyen PH, Casaburi R. Influence of muscle fibre type and fitness on the oxygen uptake/power output slope during incremental exercise in humans. Exp Physiol. 2000;85:109–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kemp G. Kinetics of muscle oxygen use, oxygen content, and blood flow during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:2463–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00709.2005. author reply 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinker JR, Haffor AS, Stephan M, Clanton TL. Kinetics of CO uptake and diffusing capacity in transition from rest to steady-state exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:1764–72. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.5.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones AM, Wilkerson DP, Wilmshurst S, Campbell IT. Influence of L-NAME on pulmonary O2 uptake kinetics during heavy-intensity cycle exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1033–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00381.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kindig CA, McDonough P, Erickson HH, Poole DC. Effect of L-NAME on oxygen uptake kinetics during heavy-intensity exercise in the horse. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(2):891–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkerson DP, Campbell IT, Jones AM. Influence of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on pulmonary O2 uptake kinetics during supra-maximal exercise in humans. J Physiol. 2004;561:623–35. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finol HJ, Montagnani S, Marquez A, Montes de Oca I, Muller B. Ultrastructural pathology of skeletal muscle in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:210–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumark T. Ultrastructural study of neuromuscular and vascular changes in connective-tissue diseases. Int J Tissue React. 1986;8:111–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norton WL. Endothelial inclusions in active lesions of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Lab Clin Med. 1969;74:369–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norton WL. Comparison of the microangiopathy of systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, scleroderma, and diabetes mellitus. Lab Invest. 1970;22:301–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norton WL, Hurd ER, Lewis DC, Ziff M. Evidence of microvascular injury in scleroderma and systemic lupus erythematosus: quantitative study of the microvascular bed. J Lab Clin Med. 1968;71:919–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gandevia B, Tovell A. Declaration of Helsinki. Medical Journal of Austria. 1964;2:320–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beaver WL, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ. A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60:2020–7. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.6.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cade WT, Nabar SR, Keyser RE. Reproducibility of the exponential rise technique of CO(2) rebreathing for measuring P(v)CO(2) and C(v)CO(2 )to non-invasively estimate cardiac output during incremental, maximal treadmill exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91:669–76. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-1017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cade WT, Fantry LE, Nabar SR, Shaw DK, Keyser RE. Impaired oxygen on-kinetics in persons with human immunodeficiency virus are not due to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1831–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Handler CE, Sowton E. A comparison of the Naughton and modified Bruce treadmill exercise protocols in their ability to detect ischaemic abnormalities six weeks after myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1984;5:752–5. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.KIRKWOOD B. Essentials of Medical Statistics. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howley ET, Bassett DR, Jr, Welch HG. Criteria for maximal oxygen uptake: review and commentary. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:1292–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruce RA, Kusumi F, Hosmer D. Maximal oxygen intake and nomographic assessment of functional aerobic impairment in cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 1973;85:546–62. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(73)90502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruce RA, Kusumi F, Niederberger M, Petersen JL. Cardiovascular mechanisms of functional aerobic impairment in patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1974;49:696–702. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.49.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farrell PA, Wilmore JH, Coyle EF, Billing JE, Costill DL. Plasma lactate accumulation and distance running performance. Med Sci Sports. 1979;11:338–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cerretelli P, Ambrosoli G, Fumagalli M. Anaerobic recovery in man. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1975;34:141–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00999926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang YY, Johnson MC, 2nd, Chow N, Wasserman K. The role of fitness on VO2 and VCO2 kinetics in response to proportional step increases in work rate. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1991;63:94–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00235176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hughson RL, Morrissey M. Delayed kinetics of respiratory gas exchange in the transition from prior exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1982;52:921–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.4.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagberg JM, Nagle FJ, Carlson JL. Transient O2 uptake response at the onset of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1978;44:90–2. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arena R, Humphrey R, Peberdy MA. Measurement of oxygen consumption on-kinetics during exercise: implications for patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2001;7:302–10. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2001.27666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arena R, Humphrey R, Peberdy MA, Madigan M. Comparison of oxygen uptake on-kinetic calculations in heart failure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1563–9. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathur RS, Revill SM, Vara DD, Walton R, Morgan MD. Comparison of peak oxygen consumption during cycle and treadmill exercise in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1995;50:829–33. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.8.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cade WT, Fantry LE, Nabar SR, Keyser RE. Decreased peak arteriovenous oxygen difference during treadmill exercise testing in individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1595–603. doi: 10.1053/s0003-9993(03)00275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cade WT, Fantry LE, Nabar SR, Shaw DK, Keyser RE. A comparison of Qt and a-vO2 in individuals with HIV taking and not taking HAART. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1108–17. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074567.61400.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Convertino VA, Goldwater DJ, Sandler H. Bedrest-induced peak VO2 reduction associated with age, gender, and aerobic capacity. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1986;57:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bostrom C, Dupre B, Tengvar P, Jansson E, Opava CH, Lundberg IE. Aerobic capacity correlates to self-assessed physical function but not to overall disease activity or organ damage in women with systemic lupus erythematosus with low-to-moderate disease activity and organ damage. Lupus. 2008;17:100–4. doi: 10.1177/0961203307085670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poole DC, Barstow TJ, McDonough P, Jones AM. Control of oxygen uptake during exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:462–74. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31815ef29b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Engelen M, Porszasz J, Riley M, Wasserman K, Maehara K, Barstow TJ. Effects of hypoxic hypoxia on O2 uptake and heart rate kinetics during heavy exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:2500–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.6.2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hughson RL, Xing HC, Butler GC, Northey DR. Effect of hypoxia on VO2 kinetics during pseudorandom binary sequence exercise. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1990;61:236–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palange P, Galassetti P, Mannix ET, et al. Oxygen effect on O2 deficit abd VO2 kinetics duering exercise in obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1995;78:2228–34. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.6.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Groebe K. A versitile model of steady state O2 supply to tissue. Application to skeletal msucle. Biophysics Journal. 1990;57:485–98. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82565-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adams NP, Bestall JC, Jones PW, Lasserson TJ, Griffiths B, Cates C. Inhaled fluticasone at different doses for chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD003534. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003534.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu F, Rhodes EC. Oxygen uptake kinetics during exercise. Sports Med. 1999;27(5):313–27. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199927050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carter H, Jones AM, Barstow TJ, Burnley M, Williams CA, Doust JH. Oxygen uptake kinetics in treadmill running and cycle ergometry: a comparison. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:899–907. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Connes P, Monchanin G, Perrey S, Wouassi D, Atchou G, Forsuh A, et al. Oxygen uptake kinetics during heavy submaximal exercise: Effect of sickle cell trait with or without alpha-thalassemia. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27:517–25. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-865823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Poole DC, Barstow TJ, Gaesser GA, Willis WT, Whipp BJ. VO2 slow component: physiological and functional significance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:1354–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Whipp BJ. The slow component of O2 uptake kinetics during heavy exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:1319–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zoladz JA, Gladden LB, Hogan MC, Nieckarz Z, Grassi B. Progressive recruitment of muscle fibers is not necessary for the slow component of VO2 kinetics. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:575–80. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01129.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oxenhandler R, Hart MN, Bickel J, Scearce D, Durham J, Irvin W. Pathologic features of muscle in systemic lupus erythematosus: a biopsy series with comparative clinical and immunopathologic observations. Hum Pathol. 1982;13:745–57. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(82)80298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Caputo F, Mello MT, Denadai BS. Oxygen uptake kinetics and time to exhaustion in cycling and running: a comparison between trained and untrained subjects. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2003;111:461–6. doi: 10.3109/13813450312331342337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marwood S, Roche D, Rowland T, Garrard M, Unnithan VB. Faster pulmonary oxygen uptake kinetics in trained versus untrained male adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 42:127–34. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181af20d0. Epub 2009/12/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barstow TJ, Scremin AM, Mutton DL, Kunkel CF, Cagle TG, Whipp BJ. Changes in gas exchange kinetics with training in patients with spinal cord injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28:1221–8. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brandenburg SL, Reusch JE, Bauer TA, Jeffers BW, Hiatt WR, Regensteiner JG. Effects of exercise training on oxygen uptake kinetic responses in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1640–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.10.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Murias JM, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH. Speeding of VO2 kinetics with endurance training in old and young men is associated with improved matching of local O2 delivery to muscle O2 utilization. J Appl Physiol. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01355.2009. Epub 2010/02/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carvalho MR, Sato EI, Tebexreni AS, Heidecher RT, Schenkman S, Neto TL. Effects of supervised cardiovascular training program on exercise tolerance, aerobic capacity, and quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:838–44. doi: 10.1002/art.21605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lim S, Foye P. Steroid Myopathy 2008 [cited 2010 May] Available from: URL: Http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/313842-overview.

- 77.Short KR, Nygren J, Bigelow ML, Nair KS. Effect of short-term prednisone use on blood flow, muscle protein metabolism, and function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:6198–207. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kobashigawa JA, Leaf DA, Lee N, Gleeson MP, Liu H, Hamilton MA, et al. A controlled trial of exercise rehabilitation after heart transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:272–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901283400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.DeLorey DS, Kowalchuk JM, Heenan AP, Dumanoir GR, Paterson DH. Prior exercise speeds pulmonary O2 uptake kinetics by increases in both local muscle O2 availability and O2 utilization. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:771–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01061.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Endo M, Usui S, Fukuoka Y, Miura A, Rossiter HB, Fukuba Y. Effects of priming exercise intensity on the dynamic linearity of the pulmonary VO(2) response during heavy exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91:545–54. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-1005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gurd BJ, Peters SJ, Heigenhauser GJ, LeBlanc PJ, Doherty TJ, Paterson DH, et al. Prior heavy exercise elevates pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and speeds O2 uptake kinetics during subsequent moderate-intensity exercise in healthy young adults. J Physiol. 2006;577:985–96. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dean TM, Perreault L, Mazzeo RS, Horton TJ. No effect of menstrual cycle phase on lactate threshold. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:2537–43. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00672.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lebrun CM, Petit MA, McKenzie DC, Taunton JE, Prior JC. Decreased maximal aerobic capacity with use of a triphasic oral contraceptive in highly active women: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:315–20. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.4.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]