Abstract

Manganese is an essential transition metal that, among other functions, can act independently of proteins to either defend against or promote oxidative stress and disease. The majority of cellular manganese exists as low molecular-weight Mn2+ complexes, and the balance between opposing “essential” and “toxic” roles is thought to be governed by the nature of the ligands coordinating Mn2+. Until now, it has been impossible to determine manganese speciation within intact, viable cells, but we here report that this speciation can be probed through measurements of 1H and 31P electron-nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) signal intensities for intracellular Mn2+. Application of this approach to yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cells, and two pairs of yeast mutants genetically engineered to enhance or suppress the accumulation of manganese or phosphates, supports an in vivo role for the orthophosphate complex of Mn2+ in resistance to oxidative stress, thereby corroborating in vitro studies that demonstrated superoxide dismutase activity for this species.

Keywords: ENDOR, phosphate, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, superoxide dismutase

Manganese is an essential transition metal that is required by organisms ranging from simple bacteria to humans (1). Although manganese is most commonly associated with its role as a catalytic and/or structural protein cofactor (1, 2), the majority of manganese is thought to be present as low molecular-weight Mn2+ complexes (3) that, among other functions, can act independently of proteins to either defend (4–9) against or promote (10, 11) oxidative stress and disease. The balance between opposing “essential” and “toxic” roles is thought to be governed by the nature of the ligands coordinating manganese. For example, orthophosphate and carboxylate complexes of Mn2+ have the capacity to act as antioxidants by lowering superoxide concentrations (12, 13), whereas the purine and hexa-aquo complexes may induce neurodegeneration by catalyzing the autoxidation of dopamine (14, 15). Thus, an understanding of manganese speciation in cells is critical for deciphering the mechanisms by which cells appropriately handle this “essential toxin”, and for addressing the role of manganese in human health and disease.

Unfortunately, standard analytical procedures that employ lysis and fractionation of cells or isolated organelles cannot be used to determine Mn2+ speciation because low molecular-weight Mn2+ complexes exchange their ligands very rapidly in solution (16), and such procedures therefore inherently alter speciation (5). Only a method of analyzing speciation in situ, using live cells and intact isolated organelles, can provide the required information. X-ray spectroscopic techniques can measure the amounts and distribution of metal ions such as Mn2+ in cells (17), and give the oxidation state(s) of Mn as well as some information about speciation (18). Herein we show that it is possible to probe Mn2+ speciation in intact, viable cells through measurements of 1H and 31P pulsed electron-nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) (19) signal intensities for intracellular Mn2+. ENDOR of a paramagnetic metal-ion center such as Mn2+ provides an NMR spectrum of the nuclei that are hyperfine-coupled to the electron spin, and thus can be used to identify and characterize coordinating ligands (20). We apply this technique to explore the relationship between manganese-phosphate interactions and oxidative stress resistance in mutants of the genetically tractable Baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) that have been engineered to exhibit altered manganese and phosphate homeostasis. These measurements reveal a striking correlation between the in vivo concentration of orthophosphate (Pi) complexes of Mn2+ with oxidative stress resistance, thereby supporting previous in vitro studies that demonstrated the superoxide dismutase activity of the Mn2+-Pi complex (13).

Results

Genetic Perturbation of Manganese and Phosphate Homeostasis.

To probe variations in manganese-phosphate speciation in cells, and their possible correlations with resistance to oxidative stress, we employed genetically engineered pairs of strains of S. cerevisiae designed to alter the levels of accumulated manganese or phosphate and used atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) to measure the cellular manganese and biochemical methods to measure phosphate levels that were achieved (See SI Text). As shown in Table 1, the smf2 strain, lacking the Smf2p Nramp manganese transporter (21, 22), accumulates manganese at tenfold lower levels than the wild-type (WT) yeast, whereas the pmr1Δ mutant, lacking the Mn transporting ATPase for the Golgi (23, 24), accumulates sevenfold higher levels of manganese. The table further shows that these disruptions to manganese homeostasis have no major effects on intracellular phosphates levels.

Table 1.

Total cellular manganese and phosphate in yeast mutants

| Phosphate (mM) |

|||

| Strain | Mn (uM) | Pi | pP |

| WT | 26 | 42 | 23 |

| pmr1 | 170 | 35 | 20 |

| smf2 | 2.4 | 55 | 27 |

| pho85 | 35 | 290 | 140 |

| vph1 | 29 | 10 | 5 |

To alter phosphate levels specifically, we targeted the Vph1p subunit of the vacuolar ATPase, needed for phosphate accumulation (4, 25), and the Pho85p kinase, which negatively controls phosphate uptake and storage (25–27). As shown in Table 1, the resulting vph1 and pho85 strains respectively exhibit a fourfold decrease and an eightfold increase in cellular Pi, polyphosphate (pP), and total phosphates concentrations, with negligible changes in manganese concentrations. These pairs of mutants with elevated and lowered phosphates (pho85 and vph1) and manganese (pmr1 and smf2) provide an ideal test of the utility of EPR and ENDOR spectroscopy for probing Mn-P speciation in intact cells and its effects on oxidative stress resistance.

Probing Mn2+ Speciation Using EPR and Electron-Nuclear Double Resonance Spectroscopies.

Continuous Wave EPR spectra of all the yeast strains, taken at X (9 GHz), Q (35 GHz), and W (95 GHz) bands and electron-spin echo EPR spectra at 35 GHz all show only intense signals from low molecular-weight Mn2+ (S = 5/2) complexes, with no evidence of the broader features associated with Mn2+ enzymes (28–30). However, we find that EPR spectroscopy is not sensitive to the speciation of Mn2+ complexed with biologically available ligands (Fig. S1).

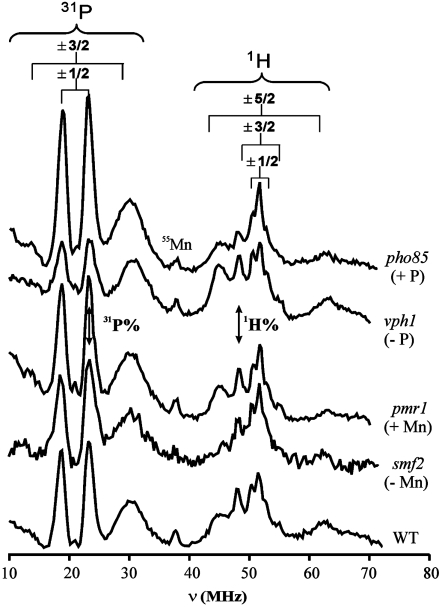

In contrast, 35 GHz Davies pulsed ENDOR (19) spectra reveal details of Mn2+ speciation in viable yeast cells. Fig. 1 presents whole-cell ENDOR spectra of WT yeast and of the strains with genetically engineered perturbations of Mn and phosphate homeostasis, while Fig. S2 presents those of Mn2+ in aqueous solution and in the presence of saturating amounts of Pi and pP. The 31P spectra for ATP and pP complexes are the same, so any ATP contribution is combined with that of pP. All spectra show 1H signals that can be assigned to the protons of bound water (31–33). As indicated, these signals include resolved doublets associated with the main (ms = ± 1/2) Mn2+ EPR transition, each centered at the 1H Larmor frequency and split by its hyperfine interaction, along with satellite features associated with the electron-spin ms = ± 3/2, ± 5/2 electron-spin transitions. The spectra of all strains and of the phosphates standards also show a sharp ms = ± 1/2 31P doublet from a phosphate moiety bound to Mn2+ (28, 32) as well as 31P ms = ± 3/2 satellite peaks. Thus, all the yeast strains contain populations of Mn2+ with aquo and phosphato ligands. In contrast, careful investigation reveals no 14N signals, which indicates that the cells contain no significant populations of Mn2+ coordinated by nitrogenous ligands.

Fig. 1.

35 GHz Davies pulsed ENDOR spectra of the several yeast strains discussed here, with the 1H and 31P features from the individual Mn2+ (S = 5/2) substates indicated. “Mn” corresponds to the third harmonic of a 55Mn transition that was not filtered out, leaving a fiduciary mark. The double-headed arrows indicate the features used to quantitate the ENDOR intensities. Conditions: T = 2 K, MW pulse = 60 ns, τ = 700 ns, RF pulse = 40 μs, repetition time = 20 ms.

The 31P and 1H ENDOR signals for the standards (Fig. S2) and yeast strains (Fig. 1) all exhibit similar 31P and 1H hyperfine couplings, so it is not possible to use the values of the couplings to decompose the spectra into contributions from individual species. However, the intensities of these signals for the different standard reference species differ significantly (Fig. S2), and analysis of the 31P and 1H intensities does provide a means of assessing speciation and its variation with changes in homeostasis.

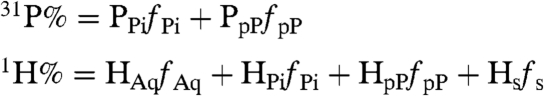

As Mn2+ enzymes contribute negligibly to the cellular EPR signals, the observed cellular ENDOR responses, 31P% and 1H%, can be formulated in terms of the fractional populations, fi, and absolute ENDOR responses, Pi and Hi, for each of four low molecular-weight species present: Mn2+ complexes with bound (i) Pi, (ii) pP, and (iii) ENDOR-silent ligands (denoted, Mn2+-s; s), as well as (iv) the hexa-aquo-Mn2+ ion (denoted Mn2+-aqua; Aq):

|

[1.1] |

| [1.2] |

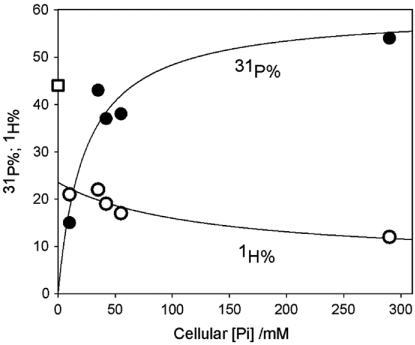

The presence of the Mn2+-s species is suggested by considering the variation of 1H% and 31P% across the suite of yeast variants, as collected in Table 2. The 31P% rises smoothly with phosphates concentration; a plot (Fig. 2) as a function of the analytically derived total [Pi] (Table 1) presents the appearance of a simple binding isotherm versus [Pi], even though both Pi- and pP-bound Mn2+ must be contributing to the signal. The corresponding 1H% shows a correlated decrease, as expected if Mn2+-bound H2O is being replaced by Pi and pP. However, extrapolation of the cellular 1H% back to [Pi] = 0 only yields a value roughly half that for hexa-aquo-Mn2+, which implies there is a population of Mn2+ bound by ENDOR-silent ligands, presumably carboxylato metabolites, which also displace bound H2O.

Table 2.

ENDOR-derived Mn2+ average/effective speciation*

| Experimental† |

Assigned‡ |

Calculated* |

||||||||

| Mutation | Strain | 31P% | 1H% | [Pi]/mM | [pP]/mM | fPi(%) | fpP(%) | fP(%) | FAq(%) | fs(%) |

| WT | 37 | 19 | 42 | 0.6(0.2) | 47(10) | 24(4) | 71(6) | 5(3) | 24(7) | |

| Mn(−) | smf2 | 38 | 17 | 55 | 0.9(0.2) | 38(11) | 32(4) | 70(7) | 3(2) | 27(7) |

| Mn(+) | ||||||||||

| pmr1 | 43 | 22 | 35 | 0.5(0.1) | 60(10) | 25(5) | 85(6) | 7(4) | 8(7) | |

| P(−) | vph1 | 15 | 21 | 8§ | 0(0.2) | 34(7) | 0(+7) | 34(6) | 16(5) | 50(8) |

| P(+) | ||||||||||

| pho85 | 54 | 12 | 290 | 6(2) | 12(10) | 73(5) | 85(7) | 0 | 15(7) | |

*Fractions (fi) of Mn2+ bound to Pi(i = Pi), pP(i = pP), ENDOR-silent ligands (i = s), or present as Mn2+-aqua (i = Aq) calculated from [31P%, 1H%] (See Text and SI Text). Uncertainties are the larger of those calculated from uncertainties in 31P% and 1H% (†) or by increasing/decreasing the assigned [Pi], 2-fold (‡).

†ENDOR-response; 10× percentage change in Electron Spin Echo (ESE) intensity measurements on four samples yield uncertainties, ± 2.

‡Except as noted, speciation calculated with the experimental [Pi] from Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Plot for yeast strains of cellular 31P% (solid circles) and 1H% (open circles) versus Pi concentration. The lines are to guide the eye, but correspond to fits of the data to a simple one-site binding isotherm with  . The square corresponds to 1H% for Mn2+ - aqua.

. The square corresponds to 1H% for Mn2+ - aqua.

The absolute ENDOR responses for Mn2+-aqua were obtained from Mn2+ in aqueous solution (Fig. S2); those for Pi- and pP-bound Mn2+ from titrations of Mn2+ with Pi or pP (Figs. S3, S4). The Pi titration fits well to the isotherm in which a single Pi binds to Mn2+-aqua, replacing one H2O (Fig. S4); the pP titration instead is well-fit by an isotherm in which Mn2+-aqua cooperatively binds n = 2 pP chelates (Fig. S4), losing all or most of its water. In agreement with published reports (34, 35), pP binds to Mn2+ with an affinity constant roughly two–three orders of magnitude greater than Pi. Competition experiments show that Pi and pP bind competitively, with negligible formation of mixed-ligand complexes, justifying the formulation of Eq. 1.1 in terms of distinct Pi and pP-bound species.

Of the four fi, three must be determined experimentally; we take these to be fs, fPi, and fpP. The fourth, fAq then is fixed by the normalization condition, Eq. 1.2. Of the three unknowns, fPi and fpP can be expressed in terms of fs and (parametrically) the Pi and pP concentrations through use of the corresponding phosphates binding isotherms (SI Text), leading to the formulation of Eq. 1.1 in terms of the three unknowns, [Pi], [pP], and fs. It is possible to solve for the effective whole-cell fi, namely the average whole-cell speciation, through use of the two experimental 31P% and 1H% ENDOR responses by assigning each cell line an effective Pi concentration equal to the measured cellular Pi concentration, Table 1; the results for the yeast strains studied are presented in Table 2.

Speciation in WT Yeast and Variants with Perturbed Manganese and Phosphates Homeostasis.

WT yeast:

Decomposition of the ENDOR spectrum of the Mn2+ in WT yeast into its four component complexes as described above, Table 2, indicates that nearly three-fourths is bound to phosphates, with the majority of this as the Pi complex. Approximately one-fourth is coordinated by ENDOR-silent ligands, and there is minimal Mn2+-aqua.

Mn homeostasis variants:

The electron-spin echo intensities of the low-Mn smf2 and high-Mn pmr1 strains change relative to that of WT yeast in parallel with changes in the total manganese concentrations, as expected for Mn2+ as the dominant oxidation state (18), while the signal shapes are invariant. The ENDOR response of the low-Mn smf2 strain is essentially unchanged from that of WT yeast, Fig. 1, as is the computed speciation, Table 2. Thus, although this mutation strongly decreases the total cellular Mn and slightly alters the total phosphates, the Mn2+ speciation is unaltered. As this speciation reflects an interplay among the manganese distribution between cellular compartments, the concentration of phosphates within and/or among these compartments, as well as the availability of ENDOR-silent ligands, it would seem that all these are essentially unchanged by this mutation.

In contrast, the speciation of the additional Mn2+ in the high-Mn pmr1 mutant strain is notably different from that in WT yeast, Table 2. Most noticeably, the amount of phosphates-bound Mn2+ in this strain has increased to roughly 90% of the total Mn2+ of the cell, the increase reflecting conversion of Mn2+ coordinated to ENDOR-silent ligands to Pi-coordinated Mn2+.

Phosphates homeostasis variants:

The vph1 (low phosphates) and pho85 (high phosphates) (Table 1) mutations do not significantly modify [Mn] (Table 1), and as expected, the electron-spin echo intensities from these cells were roughly unchanged from WT.

vph1: The ENDOR spectrum of this low-phosphates strain shows a more than twofold decrease in 31P% relative to that for WT, accompanied by a slight increase in 1H% (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Both changes indicate decreased coordination of Mn2+ by phosphates. The calculated Mn2+ speciation of vph1 (Table 2) shows a roughly twofold decrease in the total fraction of phosphates-bound Mn2+ compared to WT yeast, down to about one-third of the total, with most as the pP complex. About half of the Mn2+ in this strain is bound to ENDOR-silent ligands, and this is the only cell type examined that is calculated to have a significant amount of Mn2+-aqua.

pho85: The ENDOR spectrum of this strain (Fig. 1) changes relative to the spectrum of WT cells in ways that might have been anticipated for a cell with increased phosphate levels: marked increase in 31P% response and decrease in 1H% response. These changes correspond to dramatic changes in Mn2+ speciation (Table 2), with ∼85% of the Mn2+ bound to phosphates. The majority exists as the pP complex, a result that nicely parallels the sharp increase in [pP] measured analytically (Table 1). The remainder of the Mn2+ is mostly in ENDOR-silent complexes.

Mn2+-L concentrations:

The yeast strains exhibit wide variations in the total Mn concentration, Table 1, so the speciation fractions, fi, of Table 2 have been converted to the biologically relevant concentrations of the different Mn2+ species through multiplication by the total Mn concentrations, and these are given in Table 3. This calculation assumes that negligible amounts of Mn occur as Mn3+, a reasonable first-approximation as demonstrated by X-ray spectroscopy (18) and the fact that Mn-SOD, a principal repository of Mn3+, is present at ∼0.3 μM (10,900 molecules per cell) (36), which constitutes ∼1% of the total Mn (Table 1).

Table 3.

Correlation of the oxygen resistance of sod1Δ yeast mutants with concentrations of various cellular Mn(II) complexes (μM)

Oxygen Sensitivity of the Manganese-Phosphate Mutants.

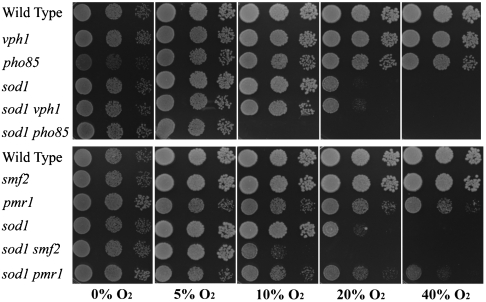

As seen in Fig. 3, sod1Δ mutants grow poorly in atmospheric (20%) oxygen and not at all at higher O2. This oxygen sensitivity is rescued by the pmr1Δ mutation, which causes cells to accumulate very high concentrations of Mn-Pi (greater than 100 μM; Table 3). By comparison, the vph1 mutation, which leads to WT levels of [Mn2+-Pi] (∼10 μM; Table 3) does not affect sod1Δ oxygen tolerance (Fig. 2), and the smf2Δ mutation, which leads to very low accumulation of Mn2+-Pi (< 1 μM), causes severe oxidative stress to the point that the sod1Δ smf2Δ double mutant is not viable in atmospheric oxygen. Aerobic growth of sod1Δ cells also is prevented by a pho85Δ mutation that lowers [Mn2+-Pi] to about one-third of WT levels (Table 3), in spite of elevated total phosphate (Table 1). These observations all are consistent with the interpretation that Mn2+-Pi can compensate for loss of Sod1p function.

Fig. 3.

Oxygen sensitivity of the phosphate and manganese mutant strains. 104, 103, and 102 cells of each of the indicated strains were plated on YPDE plates and incubated at 30 °C under varying oxygen tensions for 3 d.

It is noteworthy however that the strain with the lowest [Mn2+-Pi] (smf2) is not the most sensitive to oxidative stress. Rather, in an apparent deviation from the correlation between oxidative stress resistance and [Mn2+-Pi], the pho85 mutation confers extreme oxidative stress sensitivity to sod1Δ cells: the sod1Δ pho85Δ strain is inviable even at 10% O2 (Fig. 3). Severe sensitivity to oxygen also has been reported for the sod1Δ pho80Δ strain, which lacks the Pho80p cyclin partner to Pho85p (4). However, our preliminary studies indicate that loss of the Pho85p cyclin-dependent kinase not only alters Pi and pP levels, but activates a Rim15p-dependent signaling pathway, thereby exacerbating the oxidative damage caused by the decrease in [Mn2+-Pi] (37). Aside from this nonphosphate effect of pho85 on oxidative stress, the observed correlation between cellular [Mn2+-Pi] and oxidative stress resistance strongly supports the notion that Mn2+-Pi is a genuine cellular antioxidant, and that it is responsible for Mn antioxidant activity.

Discussion

Herein, we show that Mn2+ speciation in viable cells can be probed through measurements of whole-cell 1H and 31P pulsed ENDOR signal intensities and describe a procedure that decomposes the ENDOR spectra into the average/effective contributions from complexes with: (i)  (Pi), (ii) polyphosphate (pP), and (iii) ENDOR-silent ligands, as well as from (iv) hexa-aquo Mn2+. The in vivo study of low molecular-weight complexes of Mn2+ can be profitably compared and contrasted with the study of biological Fe speciation. Fe is readily examined with multiple tools, including Mossbauer, EPR, X-ray absorption, and optical spectroscopies (38, 39), whereas it is likely that only X-ray absorption methods (6, 18, 40) can complement ENDOR studies of cellular Mn2+.

(Pi), (ii) polyphosphate (pP), and (iii) ENDOR-silent ligands, as well as from (iv) hexa-aquo Mn2+. The in vivo study of low molecular-weight complexes of Mn2+ can be profitably compared and contrasted with the study of biological Fe speciation. Fe is readily examined with multiple tools, including Mossbauer, EPR, X-ray absorption, and optical spectroscopies (38, 39), whereas it is likely that only X-ray absorption methods (6, 18, 40) can complement ENDOR studies of cellular Mn2+.

The ENDOR measurements show that speciation is not altered when Mn levels are strongly decreased (smf2, Table 2). However, when Mn accumulation is sharply increased (pmr1), the average fraction of phosphates-bound Mn2+, particularly the Pi-bound complex, increases noticeably, despite the fact that the total cellular accumulation of phosphates is slightly diminished by this mutation (Table 1). Thus, the speciation measurements suggest that the additional Mn2+ in pmr1 cells is differently distributed within cellular compartments than in WT cells.

Mn2+ speciation is strongly altered by changes in phosphates concentrations. In the vph1 mutant strain, which exhibits low levels of phosphates, only approximately one-third of the Mn2+ is phosphates bound, compared to over two-thirds in WT yeast, while about one-half of the vph1 manganese is bound by ENDOR-silent, presumably carboxylato, metabolites, up from the one-quarter that is bound to such ligands in WT yeast. In contrast, in pho85 cells, which accumulate high levels of intracellular phosphates, about four-fifths of the Mn2+ is phosphate bound, mostly in pP chelates, with less than one-sixth bound to ENDOR-silent ligands.

The ENDOR spectroscopic studies described herein agree with previous in vitro studies that have implicated manganous Pi complexes as potential antioxidants and as protecting cells against oxidative damage (13). They reveal a correlation of the viability of sod1 mutants under atmospheric oxygen with the concentration of Mn2+-Pi , but not with the concentrations of Mn2+-pP, Mn2+-aqua, or Mn2+-s (Table 3), or even with total [Pi] and/or [pP] (Table 1). For instance, the sod1 pmr1 mutant has the greatest [Mn-Pi] concentration and is most resistant to oxygen stress, whereas the sod1 smf2 and sod1 pho85 mutants have the smallest [Mn-Pi] and are most sensitive to oxygen. It is important to note that without the application of ENDOR spectroscopy, one might have reached the opposite conclusion based on the analytical results, namely, that in vivo manganese-Pi interactions do not correlate with oxidative stress resistance (4). The present use of ENDOR to probe whole-cell Mn2+ speciation, which allows us to distinguish between Mn2+-Pi and Mn2+-pP, thus reveals the potential hazard of assuming a transition metal speciation based on altered total cellular concentrations of a given ligand, thereby highlighting the importance of in situ biophysical techniques to probe metal speciation.

The pulsed ENDOR protocol has provided information about the Mn2+ speciation as averaged over the whole cell, whereas speciation is likely to differ in different cell compartments and metal concentrations to vary across the cell (17). To address this issue, experiments are under way on isolated, intact organelles, including vacuoles, mitochondria, and nuclei, as well as on other strains and organisms.

Methods

Yeast Strains, Growth Conditions, and Biochemical Assays.

All yeast strains in this study were derived from BY4741 (MATa, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0, his3Δ1), and were either purchased from the commercially available kanMX4 deletion collection or genetically engineered as described in SI Text.

Experiments employed cells freshly obtained from frozen stocks and cultured on a yeast extract, peptone, dextrose medium (YPD) media at 30 °C (41). For experiments involving sod1Δ mutants, cells were precultured anaerobically on YPD medium supplemented with 15 mg/L ergosterol and 0.5% Tween 80 (YPDE) media and grown at 30 °C in anaerobic chambers (GasPak, Becton-Dickinson). For EPR/ENDOR analysis of yeast cells, cultures were inoculated, grown in YPD media, washed, and prepared in EPR tubes as described in SI Text.

To assay for oxygen sensitivity, yeast strains were serially diluted onto YPDE plates and grown under atmospheres of 0%, 10%, 20%, or 40% O2, balance N2, for 3 d at 30 °C, as described in detail in SI Text.

Cellular manganese and phosphate content of cells was determined by AAS and the colorimetric molybdate assay for phosphates, respectively, as described in SI Text.

Electron-Nuclear Double Resonance Measurements.

35 GHz pulsed EPR and Davies ENDOR spectra were collected on a laboratory-built spectrometer; W-band (95 GHz) CW EPR spectra were collected on a laboratory-designed homodyne spectrometer: see SI Text.The absolute 31P and 1H ENDOR intensities, denoted 31P% and 1H%, are defined as the percentage changes in the electron-spin-echo signal (x10) as manifest in Davies ENDOR spectra collected as described in SI Text. The values of Table 2 are measured as changes in intensity of the peaks indicated in Fig. 1; integrations of the 31P peak or of all or part of the 1H pattern gave equivalent results (see SI Text). The 31P% and 1H% are reproducible within ∼2% for a given sample; entries in Table 2 are the averages of four separate preparations of each yeast strain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We acknowledge many helpful discussions with Dr. Peter Doan, a helpful discussion with Prof. Helmut Sigel, and funding by the National Institutes of Health (NIH): (HL13531, (to B.M.H.); ES 08996, GM 50016, (to V.C.C.); DK 46828, (to J.S.V.)), the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) National Institute on Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Center (ES 07141, to A.R.R. and L.R.), NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) National Research Service Award (NRSA) postdoctoral fellowship (F32GM093550, (to A.R.R.)). This work also was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Fund/Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (KOSEF/MEST) through World Class University (WCU) project (R31-2008-000-10010-0, (to J.S.V.)).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1009648107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sigel A, Sigel H. Metal ions in biological systems. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wieghardt K. The active sites in manganese-containing metalloproteins and inorganic model complexes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1989;28:1153–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galiazzo F, Pedersen JZ, Civitareale P, Schiesser A, Rotilio G. Manganese accumulation in yeast cells. Electron spin resonance characterization and superoxide dismutase activity. Biol Met. 1989;2:6–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01116194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddi AR, et al. The overlapping roles of manganese and Cu/Zn SOD in oxidative stress protection. Free Radical Biol Med. 2009;46:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Maghrebi M, Fridovich I, Benov L. Manganese supplementation relieves the phenotypic deficits seen in superoxide-dismutase-null Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;402:104–109. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daly MJ. A new perspective on radiation resistance based on Deinococcus radiodurans. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:237–245. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archibald FS, Fridovich I. Manganese and defenses against oxygen toxicity in Lactobacillus plantarum. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:442–451. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.1.442-451.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin Y-T, et al. Manganous ion supplementation accelerates wild type development, enhances stress resistance, and rescues the life span of a short-lived Caenorhabditis elegans mutant. Free Radical Biol Med. 2006;40:1185–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez RJ, et al. Exogenous manganous ion at millimolar levels rescues all known dioxygen-sensitive phenotypes of yeast lacking CuZnSOD. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2005;10:913–923. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0044-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benedetto A, Au C, Aschner M. Manganese-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration: insights into mechanisms and genetics shared with Parkinson’s Disease. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4862–4884. doi: 10.1021/cr800536y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Worley CG, Bombick D, Allen JW, Suber RL, Aschner M. Effects of manganese on oxidative stress in CATH. a cells. Neurotoxicology. 2002;23:159–164. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(02)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Archibald FS, Fridovich I. The scavenging of superoxide radical by manganous complexes: in vitro. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;214:452–463. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnese K, Gralla EB, Cabelli DE, Selverstone Valentine J. Manganous phosphate acts as a superoxide dismutase. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4604–4606. doi: 10.1021/ja710162n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd RV. Mechanism of the manganese-catalyzed autoxidation of dopamine. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:111–116. doi: 10.1021/tx00043a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Florence TM, Stauber JL. Manganese catalysis of dopamine oxidation. Sci Total Environ. 1989;78:233–240. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(89)90036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Westmoreland TD. Correlation of relaxivity with coordination number in six-, seven-, and eight-coordinate Mn(II) complexes of pendant-arm cyclen derivatives. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:719–727. doi: 10.1021/ic8003068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McRae R, Bagchi P, Sumalekshmy S, Fahrni CJ. In situ imaging of metals in cells and tissues. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4780–4827. doi: 10.1021/cr900223a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunter TE, Gavin CE, Aschner M, Gunter KK. Speciation of manganese in cells and mitochondria: A search for the proximal cause of manganese neurotoxicity. NeuroToxicology. 2006;27:765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schweiger A, Jeschke G. Principles of pulse electron paramagnetic resonance. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman BM. ENDOR of metalloenzymes. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:522–529. doi: 10.1021/ar0202565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen A, Nelson H, Nelson N. The family of SMF metal ion transporters in yeast cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33388–33394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luk EE-C, Culotta VC. Manganese superoxide dismutase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae acquires its metal co-factor through a pathway involving the Nramp metal transporter, Smf2p. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47556–47562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lapinskas PJ, Cunningham KW, Liu XF, Fink GR, Culotta VC. Mutations in PMR1 suppress oxidative damage in yeast cells lacking superoxide dismutase. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1382–1388. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durr G, et al. The medial-Golgi ion pump Pmr1 supplies the yeast secretory pathway with Ca2+ and Mn2+ required for glycosylation, sorting, and endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1149–1162. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogawa N, DeRisi J, Brown PO. New components of a system for phosphate accumulation and polyphosphate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae revealed by genomic expression analysis. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:4309–4321. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee Y-S, Mulugu S, York JD, O'Shea EK. Regulation of a cyclin-CDK-CDK inhibitor complex by inositol pyrophosphates. Science. 2007;316:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1139080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenfeld L, et al. The effect of phosphate accumulation on metal ion homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0664-8. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsby CJ, et al. Enzyme control of small-molecule coordination in FosA as revealed by 31P pulsed ENDOR and ESE-EPR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;12:8310–8319. doi: 10.1021/ja044094e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stich TA, et al. Multifrequency pulsed EPR studies of biologically relevant manganese(II) complexes. Appl Magn Reson. 2007;31:321–341. doi: 10.1007/BF03166263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smoukov SK. EPR study of substrate binding to the Mn(II) active site of the bacterial antibiotic resistance enzyme, FosA: a better way to examine Mn(II) J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2318–2326. doi: 10.1021/ja012480f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sivaraja M, Stouch TR, Dismukes GC. Solvent structure around cations determined by proton ENDOR spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulation. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:9600–9603. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potapov A, Goldfarb D. Quantitative characterization of the Mn2+ complexes of ADP and ATPgS by W-band ENDOR. Appl Magn Reson. 2006;30:461–472. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan XL, Bernardo M, Thomann H, Scholes CP. Pulsed and continuous wave electron nuclear double-resonance patterns of aquo protons coordinated in frozen solution to high-spin Mn2+ J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5147–5157. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saha A, et al. Stability of metal ion complexes formed with methyl phosphate and hydrogen phosphate. J Biol Inorg Chem. 1996;1:231–238. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Wazer JR, Campanella DA. Structure and properties of the condensed phosphates. IV. Complex-ion formation in polyphosphate solutions. J Am Chem Soc. 1950;72:655–663. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghaemmaghami S, et al. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wanke V, Pedruzzi I, Cameroni E, Dubouloz F, De Virgilio C. Regulation of G0 entry by the Pho80-Pho85 cyclin-CDK complex. EMBO J. 2005;24:4271–4278. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garber Morales J, et al. Biophysical characterization of iron in mitochondria isolated from respiring and fermenting yeast. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5436–5444. doi: 10.1021/bi100558z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miao R, et al. EPR and Mossbauer spectroscopy of intact mitochondria isolated from Yah1p-depleted Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9888–9899. doi: 10.1021/bi801047q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miao R, et al. Biophysical characterization of the iron in mitochondria from Atm1p-depleted Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9556–9568. doi: 10.1021/bi901110n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherman F, Fink GR, Lawrence CW. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.