Abstract

To explore the relationship between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and M. tuberculosis genotypes we performed IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis on M. tuberculosis culture specimens from smear-positive TB cases in a peri-urban community in South Africa from 2001-2005. Among 151 isolates, 95 strains were identified within 26 families with 54% clustering. HIV status was associated with W-Beijing strains (p=0.009) but not with clustering per se. High frequency of clustering suggests ongoing transmission in both HIV-negative and HIV-positive individuals in this community. The strong association of W-Beijing with HIV-infection may have important implications for tuberculosis control.

Keywords: Molecular epidemiology, RFLP, Tuberculosis, HIV, Geographical Information System, W-Beijing

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and in Africa HIV is fueling the epidemic [1]. South Africa, with 28% of the global burden of HIV/TB, is undergoing rapid urbanization [2] with immigrants to the cities concentrating in poor, crowded peri-urban townships where HIV prevalence and TB incidence rates are both high [3]. We have previously described high adult HIV prevalence (23%) [4] and rapidly escalating TB notification rates [3] in a peri-urban township in Cape Town, South Africa. Escalation in TB has occurred despite a well-implemented national TB control program (based on WHO directly observed treatment, short-course strategy [5]), at the single community clinic that manages all resident TB patients. This community, with approximately 15,000 people of low socioeconomic status living in overcrowded, largely informal dwellings and well-defined in terms of geography, is uniquely suited for TB transmission studies.

The advent of molecular epidemiological tools such as IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) genotypic analysis of M. tuberculosis (Mtb) has expanded our ability to investigate and understand TB [6]. Different Mtb strains have been associated with diverse virulence, immunological responses, epidemic potentials and even drug resistance [6]. However, the relationship between specific host characteristics, such as HIV-infection, and Mtb genotypes is poorly understood. To explore the association between HIV-infection and circulating TB strains we performed RFLP analysis of Mtb isolates cultured from individuals with smear-positive pulmonary TB (PTB) in the above-mentioned study community between 2001 and 2005.

Methods

Patient Population

Sputum specimens of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear-positive TB patients, resident in the study community, were collected for genotype analysis from 2001 through 2005. Sputum specimens were obtained from patients in accordance with the National TB Control Program guidelines [7], and were labeled as study specimens at the clinical site, for identification by laboratory personnel. Age, gender, details of clinical diagnosis, outcome and HIV status were collected from the clinic TB register and patient folders. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Boards of the University of Cape Town and the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ) and participants provided informed consent.

M. tuberculosis patient isolates

Sputum specimens were assessed for the presence of Mtb bacilli by fluorescent (auramine) microscopy. Isoniazid and rifampicin susceptibility testing was performed on retreatment patients or patients still AFB+ after 2 months treatment [7]. Susceptibility testing was performed at concentrations of 1.0μg/ml for rifampicin and 0.1μg/ml and 0.2μg/ml for isoniazid (on MGITs and Middlebrooks 7H11 agar respectively). AFB-positive sputum samples were cultured on Lowenstein Jensen (LJ) slants at the research laboratory. Mtb culture positive isolates were inoculated in duplicate into 7H9 liquid media supplemented with oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC) and 15% Glycerol, and stored at -70°C.

Molecular analysis of M. tuberculosis strains

Frozen duplicate culture stock was shipped to the Public Health Research Institute (PHRI) Tuberculosis Center at UMDNJ. Culture stocks were sub-cultured on LJ slants and DNA extracted from each isolate. IS6110-based RFLP analysis was performed as described elsewhere [8]. RFLP patterns were analyzed using BioImage pattern matching software (BioImage, MI). Mtb isolates with DNA fingerprints with an identical hybridization banding pattern were considered to be the same strain and assigned a strain code following the previously described nomenclature system [9]. Mtb strains were assigned to one of nine (I – VIII and II.A) discrete synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism (sSNP) based phylogenetic lineages (sSNP clusters) inferred based on RFLP patterns and previous analysis of PHRI Mtb clinical isolates reported elsewhere [6]. In addition, strains that exhibit similar IS6110 hybridization profiles (≥65% similarity), suggesting common recent ancestry, were collectively grouped into genotype families (e.g. W-Beijing, CC and BM families) [6]. Strain clusters were defined as more than one occurrence of a specific strain in the study period. Strain patterns that were only represented once in the PHRI database and did not qualify for a family assignment were considered unique and given a default assignment (001).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Bivariate analyses employed Student's t-, chi-square and Fisher's exact tests, as appropriate. Wilcoxon ranksum test was used for comparison of median age between different groups. Patients were divided into age categories by decades (15-19, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59 and ≥60 years of age) for analysis of the distribution of the four main Mtb families by age. Chi-square test for trend was used to assess changes in strain distribution over time.

Multiple logistic regression models were developed to examine factors associated with the dominant strain families and with clustering of strains. The period between occurrence of cases within clusters was calculated based on date of TB diagnosis. ArcMap 9.2 (Esri™) Geographic Information System was used to assess the spatial distribution of Mtb strains occurring in clusters during the course of the study.

Results

Over the five year study period 467 patients were diagnosed with sputum smear-positive PTB in the study community. The study laboratory received sputum specimens for 282 patients (60% of smear-positive patients) over this period. Of the 282 patients' specimens received, 51% (n=149) were successfully cultured for RFLP analysis; 22% lost viability during shipping or storage (n=61), 21% of specimens failed to culture Mtb (n=55), and 6% were contaminated (n=17). Two patients had dual infections with 2 different strains, and therefore there were a total of 151 Mtb isolates included in this analysis.

There were no statistically significant differences found between patients with and those without RFLP data (including patients for whom we did not receive specimens) in terms of age (p=0.11), gender (p=0.63), TB category (ie new or retreatment cases) (p=0.22), multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB, resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampicin) status (p=0.15) or HIV status among those tested (p=0.58). However patients for whom we did not obtain RFLP data had a higher death rate compared to those with RFLP data (p<0.001).

Patients with RFLP results ranged in age from 14 to 67 years (median age: 36 years) and 62% were male. In total 81% were tested for HIV, and 54% of those tested were HIV-infected. In total four (3%) patients had confirmed MDR-TB. There were no TB related deaths in this cohort.

Strain patterns and associations

A total of 95 different Mtb strains were identified (including 4 unique isolates), presented in a phylogenetic framework (Figure1). Eight of the nine recognized sSNP clusters [10] were present in the community. The sSNP VI cluster comprised 49% (n=74) of the patients. Genetic variability within this group was high, with 57 strains occurring in 74 patients. The sSNP cluster II was the second largest group, with 26% (n=39) of strains.

Figure 1. M. tuberculosis strains from the study community in a phylogenetic framework.

Twenty-six different Mtb genotype families were identified; the four largest families were W-Beijing (accounting for 26% of all TB strains in the community), CC (25%), AH (11%) and BM (7%). In bivariate analysis there was no statistically significant association between the four dominant families and gender (p=0.56), age category (p=0.31), TB category (p=0.73), or outcomes of TB treatment (p=0.53). There was no change in the distribution of the main strain families across the five year period of data collection (p=0.54).

In multivariate analysis adjusting for age, gender, TB category and outcome, there was no association between HIV status and CC strain (Odds Ratio [OR]: 1.23; 95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 0.48 – 3.17), AH strain (OR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.21-2.25) or BM strain (OR: 0.26; 95% CI: 0.04-1.49). However patients with the W-Beijing strain were significantly more likely to be HIV-positive (OR: 3.65; 95% CI: 1.37-9.71).

MDR-TB

Two cases of MDR-TB were infected with W-Beijing strains; and one case each with a CC and an H strain. There was no statistical association between MDR-TB and strain (p=0.67) or HIV status (p=0.87).

Strain clusters

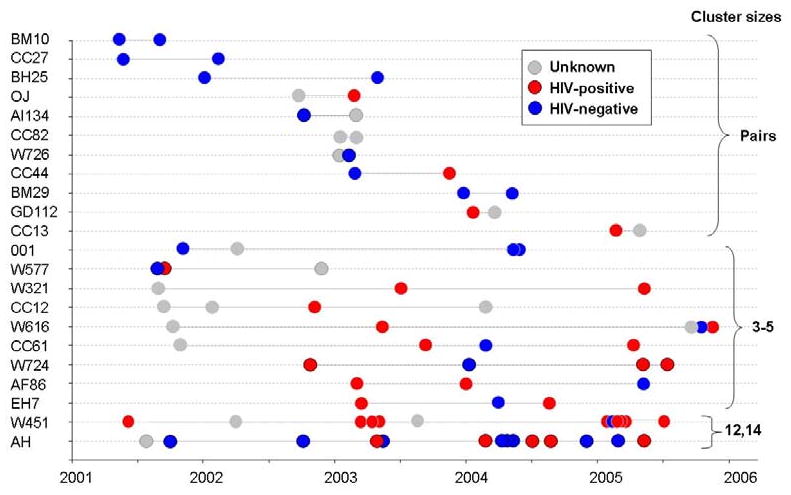

In this study, 54% (n=81) of isolates occurred in strain clusters ranging in size from 2 to 14 patients, with 27% of the clustered strains occurring in pairs. Figure 2 demonstrates the distribution of the clustered strains over time by HIV status. In multivariate analysis, there was no association between clustering and HIV status (OR: 1.20; 95% CI: 0.55-2.65). Paired clusters were diagnosed on average 157 days apart (< 6 months), as compared to an average of 321 days (>10 months) between occurrence of cases in the larger clusters (p=0.013). Smaller, temporally associated clusters were noted within the larger clusters of the W451 and AH strains. With the exception of two cases in the AH cluster, none of the clustered cases occurred on residential plot.

Figure 2. Distribution of the clusters by cluster size, date of diagnosis, HIV status and by strain family.

Discussion

The key finding of this study is the association of W-Beijing, one of the largest identified Mtb strain families, with HIV-infection. This association persisted after controlling for a number of clinical factors and could be due to either an increased pathogenicity or virulence of the strain or an increased susceptibility of HIV-infected patients to these strains. W-Beijing Mtb strains have shown marked virulence in animal models of infection [6] and it has been suggested that certain sublineages of W-Beijing may have increased transmissibility and/or pathogenecity [11]. However this is, to our knowledge, the first population-based study to show an association between W-Beijing and HIV-infection. Further understanding of the biology of the W-Beijing strains and their interaction with the HIV-infected host may help explain the increased susceptibility of HIV-infected patients to TB and may also indicate novel ways to either protect or more effectively treat HIV patients co-infected with Mtb. In other studies W-Beijing strains have been associated with multi-drug resistant TB [12]. Therefore the association with HIV-infected patients may have serious implications for the spread of MDR-TB. The increased mortality in those without RFLP analysis may reflect a lower sputum retrieval rate from the local hospital, where sicker patients were initially diagnosed.

The study has demonstrated a broad diversity of different Mtb strains, consistent with findings in other studies in sub-Saharan Africa [13;14]. The high degree of genotypic diversity within the CC strains (related to F11/LAM [13]) may indicate that they are endemic in this population. The W-Beijing family also shows a high degree of diversity (16 variants in 39 patients), although to a lesser degree than the CC family, suggesting these strains may be emerging and diversifying in the community. However, chromosomal location of IS6110 insertions may impact on the movement of the IS elements and therefore genetic diversity as determined by IS6110 RFLP may be independent of strain endemicity.

Another finding was the high rate of strain clustering. Clustering is not necessarily synonymous with recent transmission: evidence of geographical linkage, temporal association and social contacts may be needed to support the suggestion of transmission. IS6110 fingerprinting is one of the most discriminatory typing techniques for isolates with >6 IS6110 bands (eg CC and W-Beijing); although it is less discriminatory for strains with fewer bands (eg AH) [6], and may underestimate sub-clusters within the AH family. In this study approximately half of the strains were clustered and there were close temporal associations, especially among the paired clusters. A proportion of disease therefore may be due to new infections. As no association was found between HIV-infection and clustering, new infections may be occurring in both HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients. Due to the incomplete sampling from the study population we probably underestimated the number of circulating strains, number of clusters and size of clusters [15].

The spatial analysis demonstrated that temporally linked clusters did not occur on the same residential plots, suggestive of transmission outside of households. Temporally related clustering was also identified within larger clusters, such as the W451 and AH strains. The strong temporal relationship of TB infections in HIV-positive patients within the W451 strain cluster (four patients in 2003 and six patients in 2005; see figure 2) may reflect nosocomial transmission at the single community clinic. Traditional epidemiological studies, including social interaction studies are required to further delineate transmission.

In conclusion, we have shown a wide diversity of strains in this community. Strain clustering, suggestive of ongoing transmission, was common in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative adults. The W-Beijing family was associated with HIV-infection, a new finding that requires explanation and confirmation.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support. National Institutes of Health (Comprehensive Integrated Programme of Research on AIDS) grant 1U19AI053217 to K.M., L.G.B. and R.W), NIH CIPRA grant 1U19AI05321 and NIH RO1 grant AI058736-02 to R.W and NIH R01 grant AI54361 to G.K and L.G.B.

Footnotes

Potential Conflict of Interest:

Keren Middelkoop: No conflict

Linda-Gail Bekker: No conflict

Barun Mathema: No conflict

Elena Shashkina: No conflict

Natalia Kurepina: No conflict

Andrew Whitelaw: No conflict

Dorothy Fallows: No conflict

Carl Morrow: No conflict

Barry Kreiswirth: No conflict

Gilla Kaplan: No conflict

Robin Wood: No conflict

Preliminary data from this study was presented at the IAS Conference, July 2005, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Abstract TuPe7.1C28

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kok P, Collinson M. Migration and urbanisation in South Africa. Report 03-04-02. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawn SD, Bekker LG, Middelkoop K, Myer L, Wood R. Impact of HIV infection on the epidemiology of tuberculosis in a peri-urban community in South Africa: the need for age-specific interventions. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1040–1047. doi: 10.1086/501018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood R, Middelkoop K, Myer L, Grant AD, Whitelaw A, Lawn SD, Kaplan G, Huebner R, McIntyre J, Bekker LG. Undiagnosed tuberculosis in a community with high HIV prevalence: implications for tuberculosis control. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:87–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-759OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation. The Global Plan to Stop TB, 2006-2015 Stop TB Partnership. WHO Geneva; Switzerland: 2006. http://www.stoptb.org/globalplan/plan_p2main.asp?p=2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathema B, Kurepina NE, Bifani PJ, Kreiswirth BN. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis: current insights. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:658–685. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00061-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The South African Tuberculosis Control Programme. Practical Guidelines. Pretoria, South Africa: South African Department of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Embden JD, Cave MD, Crawford JT, Dale JW, Eisenach KD, Gicquel B, Hermans P, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick TM. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bifani PJ, Mathema B, Liu Z, Moghazeh SL, Shopsin B, Tempalski B, Driscol J, Frothingham R, Musser JM, Alcabes P, Kreiswirth BN. Identification of a W variant outbreak of Mycobacterium tuberculosis via population-based molecular epidemiology. JAMA. 1999;282:2321–2327. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutacker MM, Mathema B, Soini H, Shashkina E, Kreiswirth BN, Graviss EA, Musser JM. Single-nucleotide polymorphism-based population genetic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from 4 geographic sites. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:121–128. doi: 10.1086/498574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanekom M, van der Spuy GD, Streicher E, Ndabambi SL, McEvoy CR, Kidd M, Beyers N, Victor TC, van Helden PD, Warren RM. A recently evolved sublineage of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing strain family is associated with an increased ability to spread and cause disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1483–1490. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02191-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drobniewski F, Balabanova Y, Nikolayevsky V, Ruddy M, Kuznetzov S, Zakharova S, Melentyev A, Fedorin I. Drug-resistant tuberculosis, clinical virulence, and the dominance of the Beijing strain family in Russia. JAMA. 2005;293:2726–2731. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.22.2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Spuy GD, Kremer K, Ndabambi SL, Beyers N, Dunbar R, Marais BJ, van Helden PD, Warren RM. Changing Mycobacterium tuberculosis population highlights clade-specific pathogenic characteristics. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2009;89:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lockman S, Sheppard JD, Braden CR, Mwasekaga MJ, Woodley CL, Kenyon TA, Binkin NJ, Steinman M, Montsho F, Kesupile-Reed M, Hirschfeldt C, Notha M, Moeti T, Tappero JW. Molecular and conventional epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Botswana: a population-based prospective study of 301 pulmonary tuberculosis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1042–1047. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.3.1042-1047.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glynn JR, Vynnycky E, Fine PE. Influence of sampling on estimates of clustering and recent transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis derived from DNA fingerprinting techniques. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:366–371. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]