Abstract

Glutathione forms complex reaction products with formaldehyde, which can be further modified through enzymatic modification. We studied the non-enzymatic reaction between glutathione and formaldehyde and identified a bicyclic complex containing two equivalents of formaldehyde and one glutathione molecule by protein X-ray crystallography (PDB accession number 2PFG). We have also used 1H, 13C and 2D NMR spectroscopy to confirm the structure of this unusual adduct. The key feature of this adduct is the involvement of the γ-glutamyl α-amine and the Cys thiol in the formation of the bicyclic ring structure. These findings suggest that the structure of GSH allows for bi-dentate masking of the reactivity of formaldehyde. As this species predominates at near physiological pH values, we suggest this adduct may have biological significance.

Introduction

Carbonyl containing molecules, both endogenous and xenobiotic, are toxic to most organisms, and require detoxification. Thiol containing cofactors such as glutathione participate in enzymatic detoxification by the formation of adducts, which are further reduced by enzymes such as carbonyl reductase 1 (CBR1),1 or are oxidized by enzymes such as formaldehyde dehydrogenase.2 The role of the thiol containing cofactor (GSH) in such reactions is two-fold, one non-enzymatic and one enzymatic. In the non-enzymatic reaction the thiol containing cofactor forms a covalent adduct with the toxic species. This can be through interaction with the carbonyl directly (formaldehyde)3–6 to form a hemithioacetal, or with another reactive center in the molecule (i.e. α,β-unsaturated carbonyls such as prostaglandins).1 Enzymatic recognition of the cofactor-conjugate allows a single cofactor-specific enzyme to carry out efficient redox chemistry on the xenobiotic portion of the conjugate.

Although multiple cellular thiols exist, glutathione is generally considered the universal thiol coenzyme. GSH is known to be responsible for the detoxification of electrophilic species through conjugation with α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds and aldehydes. In addition to its central role in carbonyl detoxification, its importance as a nitric oxide carrier (GSNO) involved in bronchiolar dilation has been more recently uncovered.7 In the process of investigating the molecular recognition of glutathione adducts of reactive carbonyl compounds by CBR1, we uncovered a previously unreported adduct between glutathione and formaldehyde. The key feature of this adduct is the involvement of the α-NH2 of the γ-glutamyl group and the Cys thiol in the formation of the bicyclic ring structure. These findings suggest that the structure of GSH allows for bi-dentate masking of the reactivity of aldehyde containing compounds, and results in an equilibrium mixture of relatively stable species awaiting enzymatic recognition.

Previous studies of the equilibrium mixture of formaldehyde with GSH identified products that were formed in a pH and concentration-dependent fashion.8 Some of these compounds have been detected in prokaryotic organisms by use of in vivo 13C NMR techniques,9 and elucidation of the structure of others has been attempted by NMR spectroscopy and fast atom bombardment mass spectroscopy (FABMS).8 Experiments using these techniques led to proposed structures of 1 : 1 and 2 : 1 formaldehyde : GSH adducts.8 Here we have employed protein-co-crystallization using CBR1, a reductase containing an endogenous GSH binding site, to trap a 2 : 1 formaldehyde : GSH adduct present in the complex equilibrium mixture of GSH and formaldehyde. NMR experiments further validate the structure of this adduct in solution and demonstrate its presence at physiological pH.

Results and discussion

Co-crystallization of CBR1·BiGF2

In order to facilitate crystallization of formaldehyde–GSH conjugates, glutathione and formaldehyde were reacted in water (pH = 7.0), the solution was lyophilized, and the product was incubated with recombinant CBR1 and NADP. Strong diffracting crystals were grown from hanging drops, and were of space group P212121. Their structure was determined by molecular replacement with the inhibited form of CBR1 (PDB accession number 1WMA)10 as the search model. High resolution data allowed model building and refinement to 1.54 Å (Table 1). Clear difference density revealed a single bicyclic glutathione : formaldehyde (1 : 2) adduct bound within the enzyme’s active site. We have termed this ligand BiGF2, to indicate the bicyclic ring structure and the stoichiometry of the complex (GSH : 2Formaldehyde).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for the CBR1·BiGF2 complex structurea

| Title PDB code |

CBR1 with BiGF2 2PFG |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P2(1)2(1)2(1) |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c/Å | 54.636, 59.884, 87.954 |

| α, β, γ /° | 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 |

| Resolution/Å | 45.0–1.54 (1.59–1.54) |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 2.9 (6.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.5 (91.8) |

| Redundancy | 3.9 (3.4) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution/Å | 12–1.54 |

| No. reflections | 40523 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 11.2/16.3 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 2143 |

| Ligand/ion | 78/1 |

| Water | 468 |

| R.m.s. deviations: | |

| Bond lengths/Å | 0.029 |

| Bond angles/° | 2.174 |

Ramachandran for 2PFG: residues in most favored regions 91.1%, residues in additional allowed regions 8.5%, residues in generously allowed regions 0.4%, residues in disallowed regions 0%.

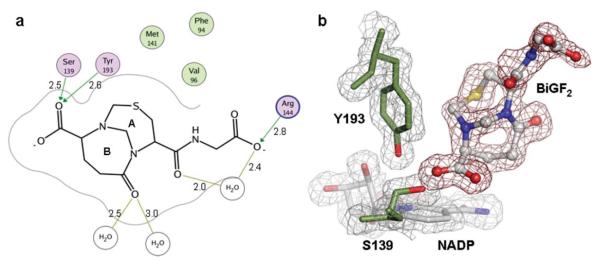

BiGF2 ((2S,7R)-7-(carboxymethylcarbamoyl)-5-oxo-9-thia-1,6-diaza-bicyclo[4.4.1]undecane-2-carboxylic acid) consists of two seven membered rings (A and B, Fig. 1A). The two large rings are bridged by one formaldehyde methylene unit that is linked to the α-amine of Cys and the α-amine of the γ-Glu portions of GSH. The second formaldehyde unit is bound to the same α-amine of the γ-Glu and to the Sγ of Cys.

Fig. 1.

(a) Binding mode of CBR1·BiGF2. Hydrogen bonding interactions and residues within a distance of 4.0 Å from the ligand are shown. Non-polar residues (green), polar residues (purple), and charged residues (purple/blue) are indicated. Distances are given (Å). (b) Electron density maps of CBR1·BiGF2. The 2Fo – Fc map is contoured in gray at a level of 1 σ. The Fo – Fc map is contoured in red at a level of 2.75 σ. NADP (gray, blue and red) and BiGF2 (grey, red, blue and yellow) are shown occupying the CBR1 active site.

Binding mode of BiGF2 to CBR1

The co-crystal structure allowed visualization of BiGF2, but its relevance to CBR1 is not clear. BiGF2 does not bind tightly to CBR1 (Ki >200 μM); however, techniques of fragment-based drug discovery11 have also demonstrated the ability of low affinity ligands to bind in protein crystal structures. In our structure, BiGF2 possessed well defined electron density allowing absolute structure elucidation. The main core of BiGF2 is bound in a hydrophobic site flanked by Phe94, Val96 and Met141 (Fig. 1A) previously unknown as a typical ligand binding site. However, electron density maps reveal the carboxylate group attached to ring B of BiGF2 (Fig. 1A) stacks above the NADP nicotinamide ring, likely stabilizing its positive charge. One of the oxygen atoms of the carboxylate interacts with Oη of Tyr139 and Oγ of Ser193 (Fig. 1A) of the catalytic machinery via hydrogen bonding. In addition to direct hydrogen bonding interactions with residues, two water molecules coordinate the glutamyl carbonyl of ring B (OE1). One of these water molecules mediates a hydrogen bonding interaction to Trp229 (OE1–H2O, 2.5 Å and H2O–Trp229 Nε1, 2.8 Å). An additional water molecule is coordinated between the glycine carboxylate oxygen (O11) and the cysteinyl carbonyl oxygen (O2). The glycine moiety is less well defined and occupies multiple conformations. During co-crystallization of BiGF2·CBR1, the presence of excess formaldehyde, not sequestered by GSH, allowed for hydroxymethylation of Sγ of Cys121 as evidenced by positive difference density fitting a covalently bound hydroxymethyl moiety (Supplementary Fig. S1†).

13C NMR for the analysis of GSH–13C formaldehyde mixtures

Previous investigations8,12 of the products formed between GSH and formaldehyde revealed a complex mixture of at least four products observable by 13C NMR when 13C enriched formaldehyde was employed. Products formed from 13C enriched formaldehyde give much simplified 13C NMR spectra as only formaldehyde and its derived methylenes are in high abundance. The complex 1H NMR spectra for these mixtures and those produced with unlabelled formaldehyde have not been assigned previously.8

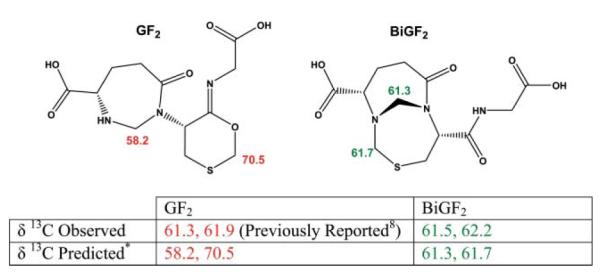

Based on 13C formaldehyde 13C NMR and mass spectrometry a compound containing two formaldehyde-derived methylene carbons (GF2, Fig. 2) was proposed to account for the 13C resonances of 61.3 and 61.9 ppm evident when glutathione and 13C formaldehyde were allowed to react in aqueous solution.8,9 We repeated these conditions and identified the same resonances (Fig. 2). Because no 13C chemical shift predictions were previously published for GF2, we carried out calculations on the molecule using ACD/CNMR DB (Advanced Chemistry Development Inc. Toronto, ON Canada). The methylene carbon resonances of GF2 were predicted at 58.2 and 70.5 ppm, vastly different from those observed. Calculations involving BiGF2, however, predict resonances of 61.3 and 61.7 ppm (Fig. 2) that closely match the experimental observations of 61.5 and 62.2 ppm. The previously reported configurational isomer (GF2) shares the formaldehyde derived methylene that is linked to the α-amine of Cys and the α-amine of the γ-glutamyl portion of GSH. Interestingly, this formaldehyde derived methylene has also been suggested to form from reaction mixtures of S-methyl glutathione and 13C formaldehyde,8 and is also found in our proposed structure, BiGF2. The second formaldehyde derived methylene of GF2 was proposed to be bound between the Sγ and O of Cys. We believe the observed 13C resonances are more likely attributable to BiGF2 rather than GF2 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Structures of the previously reported GSH : formaldehyde 2 : 1 adduct (GF2, (S)-1-((R,Z)-6-(carboxymethylimino)-1,3-oxathian-5-yl)-7-oxo-1,3-diazepane-4-carboxylic acid)8 and BiGF2 are shown. Predicted and observed 13C chemical shifts for the formaldehyde-derived methylenes are indicated.

pH Dependence of GSH–formaldehyde adduct formation

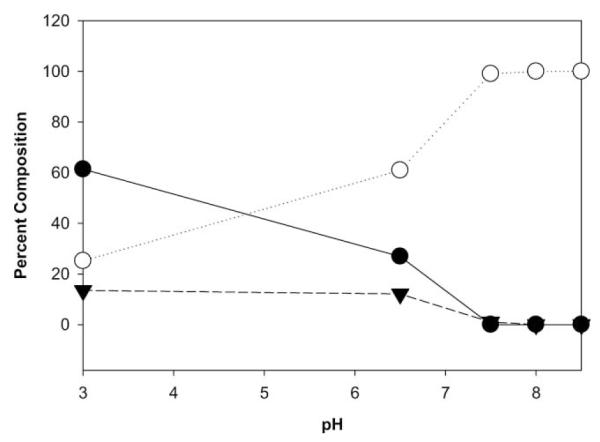

In an effort to enrich the contribution of the species responsible for the 61.5 and 62.2 ppm resonances, and to allow more detailed structural characterization in solution, we investigated the pH dependence of the mixture of GSH and formaldehyde by using 13C enriched formaldehyde. Potassium phosphate buffered samples of glutathione (13.3 mM) containing an 8-fold excess of 13C paraformaldehyde in D2O were prepared at various pH. Integration of 13C resonances derived from formaldehyde allowed an assignment of the contribution of each formaldehyde-derived compound (Supplementary Fig. S2†). At pH 7.5 and above, only a species with 13C resonances (61.5 and 62.2 ppm) along with free 13C formaldehyde (83.2 ppm) were detected by 13C NMR (Fig. 3). Thus, solutions of pH 8.5 were used to further characterize the structure of the stable adduct between GSH and formaldehyde.

Fig. 3.

Percent composition by 13C NMR of various GSH–13C formaldehyde adducts vs. pH for NMR samples containing an 8-fold excess of formaldehyde. BiGF2 (-○-, 13C NMR = 61.5 and 62.2 ppm), HMGSH (-●-, 13C NMR = 66.7 ppm) and an unidentified constituent (-▾-, 13C NMR = 44.1 ppm).

1H and 13C NMR analysis of GSH–formaldehyde mixtures

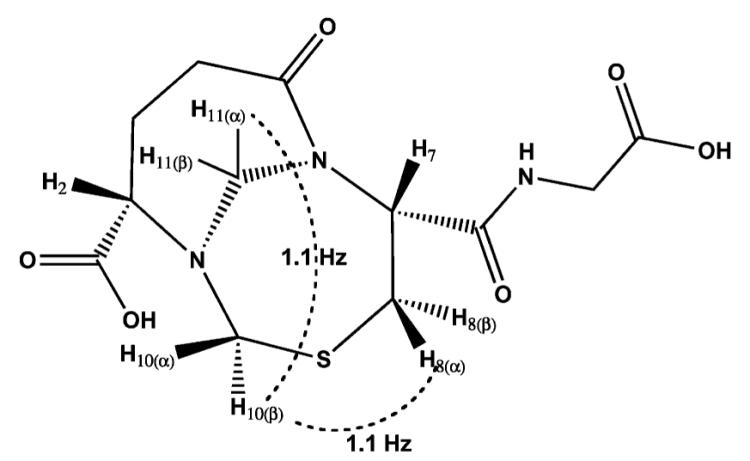

An aqueous mixture of GSH and formaldehyde was enriched for the distinct species at pH 8.5. We suggest based on our high resolution protein crystallography experiments and NMR predictions that this species is BiGF2. Therefore, we set out to assign its structure via 2D 1H NMR spectroscopy experiments using these reaction conditions. NMR samples containing glutathione and an 8-fold excess of formaldehyde were adjusted to pH 8.5, in a manner similar to those prepared with 13C formaldehyde. 13C NMR indicated the presence of 61.5 and 62.2 ppm resonances and other resonances predicted to be representative of BiGF2 (Supplementary Fig. S3†). 1H NMR spectra (Supplementary Fig. S4†) also indicated a relatively pure product, and was in accord with the BiGF2 structure. Assignment of 1H resonances was aided by COSY spectra (Supplementary Fig. S5†) demonstrating strong geminal couplings for the formaldehyde derived prochiral protons (H10 and H11, Table 2). Significantly different 1H chemical shifts were observed for these protons, indicating their presence in varied chemical environments of a rigid scaffold. Chemical shifts of 4.4 and 5.0 ppm were observed for the prochiral protons of the bridgehead 11-N,N-methylene, and chemical shifts of 3.9 and 4.2 ppm were observed for the 10-N,S-methylene. Additionally, strong geminal couplings were apparent for the prochiral protons of the Cys β-carbon (C8) and the Glu γ-carbon (C4). It was further possible to assign the formaldehyde-derived prochiral protons with the aid of selective decoupling experiments (data not shown). The pro-R proton of the bridgehead methylene (Table 2, H11(α)) exhibits rather broad lineshape due to a small coupling (1.1 Hz) to the pro-R proton of the N,S-methylene (H10(β), W-coupling through nitrogen). This pro-R proton, is also coupled (1.1 Hz) to the pro-R proton of the cysteinyl methylene (H8(α), W-coupling through sulfur). Prochiral protons of the Glu γ-carbon (C4) were not differentiated from each other because their assignment would rely on couplings to protons of the β-glutamyl carbon that have overlapping chemical shifts. This solution based NMR data is in accord with the structure of BiGF2 observed in our high resolution protein crystallography experiments.

Table 2.

Spectral assignments for protons of the bicycloundecane moiety of (2S,7R)-7-(carboxymethylcarbamoyl)-5-oxo-9-thia-1,6-diaza-bicyclo-[4.4.1]undecane-2-carboxylic acid, BiGF2. Long range W-couplings are shown as dotted lines

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Proton | Multiplicity | 1H Integration | J/Hz | δ 1H |

| 2 | dd | 1 | 3.4, 9.9 | 3.5 |

| 3 | m | 2 | 2.1 | |

| 4(α) | ddd | 1 | 4.6, 8.4, 13.7 | 3.1 |

| 4(β) | ddd | 1 | 6.9, 9.5, 16.7 | 2.7 |

| 7 | dd | 1 | 6.0, 11.8 | 5.0 |

| 8(α) pro-R | ddd | 1 | 1.1, 5.9, 15.6 | 3.5 |

| 8(β) pro-S | dd | 1 | 11.8, 15.5 | 3.2 |

| 10(α) pro-S | d | 1 | 14.1 | 4.2 |

| 10(β) pro-R | ddd | 1 | 1.1, 1.1, 14.1 | 3.9 |

| 11(α) pro-R | dd | 1 | 1.1, 15.8 | 5.0 |

| 11(β) pro-S | d | 1 | 15.8 | 4.4 |

Conclusion

Formaldehyde adducts of glutathione have been detected both in vivo9 and in vitro, and the necessity for organisms to metabolize formaldehyde generated as an intermediate during catabolism of xenobiotics is well understood.4 HMGSH formed by reaction of GSH and formaldehyde is readily catabolized. Other adducts of GSH and formaldehyde have eluded detailed study because the products vary in abundance, and have not been isolated in their pure form. Here we have utilized protein crystallography to inform the structure of an unusual adduct of GSH and formaldehyde that has eluded detection.

Recently, groups have demonstrated the utility of protein X-ray crystallography for the identification of endogenous ligands of proteins. Short chain dehydrogenase (SDR) enzymes like CBR110 frequently co-crystallize with their nicotinamide cofactors, and groups have identified inositolhexakis phosphate (IP6) buried within the enzyme core of crystallized ADAR2, an enzyme involved RNA editing.13 In addition, techniques of fragment-based drug discovery11 have demonstrated the ability of low affinity exogenous ligands to bind in protein crystal structures. In an effort to discover physiologically relevant conjugates of glutathione, we utilized protein X-ray crystallography with CBR1, a protein containing a known glutathione binding site to trap formaldehyde derived GSH ligands. It was possible to trap the previously unidentified GSH conjugate, BiGF2, for crystallographic characterization. In order to perform a detailed structural characterization and verify the presence of the same compound in solution, it was necessary to find conditions at which BiGF2 is stable. We determined that above pH 7.5, BiGF2 was exclusively present. Thus, the complete NMR characterization of BiGF2 was carried out.

Glutathione is unique in its ability to sequester two formaldehyde equivalents as a relatively stable species. Other thiol containing molecules including Cys containing proteins may transiently react with formaldehyde, but only glutathione, by virtue of the Cys nucleophile and the α-NH2 nucleophile of the γ-glutamyl moiety allow for bi-dentate “chelation” of formaldehyde. Such reactivity allows for intramolecular cross-linking by formaldehyde, and the formation of species that are expected to be favoured over those formed by intermolecular cross-linking reactions. In the absence of an appropriate dehydrogenase, glutathione, present in cells at up to 10 mM concentration has the ability to sequester formaldehyde both by the formation of HMGSH and BiGF2 at physiological pH. At low formaldehyde concentrations or low pH, HMGSH is favoured over the less reactive BiGF2, and may be metabolized by the glutathione-dependant formaldehyde dehydrogenase4 that is conserved from bacteria to humans.

Materials and methods

Chemical synthesis of S-hydroxymethylglutathione

To a solution of glutathione in water (2 mM, pH 7.0) was added 4 molar equivalents of an aqueous formaldehyde solution (27% w/w stabilized with 10–15% methanol). The solution was stirred for 1 h, frozen and lyophilized. The resultant clear solid was reconstituted in water. NMR analysis in D2O revealed complex spectra indicative of the formation of a mixture of products as previously reported.8

Carbonyl reductase assay

Carbonyl reductase activity was determined spectrophotometrically as previously described.10 Briefly, reactions contained 200 μM NADPH, 200 μM menadione, 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH = 6.8) and hCBR1 (30 nmol). Initial rates were calculated from the NADPH absorbance decrease (340 nm).

Protein expression and purification

Human carbonyl reductase 1 was overexpressed in E. coli and purified by affinity chromatography exploiting the endogenous GSH binding site.10 CBR1 expression was induced at 37 °C by the addition of IPTG to pET-11aCR harbouring E. coli BL21(DE3). Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in buffer A (pH = 7.4) containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 mM EDTA, 150 mM KCl, 0.1 mM DTT, and complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor (1 tablet per 10 mL, Roche). The suspension was subject to two passes (50 psi) through a model M-110S Microfluidizer (Microfluidics Corporation). The effluent was clarified by centrifugation (25000g, 1 h) and applied to a GSTPrep FF 16/10 column (Amersham) equilibrated with buffer B (pH = 7.4) containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 mM EDTA, 150 mM KCl, 0.1 mM DTT, and 0.1% NP40. The column was washed with buffer B (15 column volumes), and the protein was eluted over a 5 column volume gradient to 100% buffer C (pH = 6.8) containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 M KCl, 0.1 mM DTT and 20 mM glutathione. The purified protein solution was dialyzed for 16 h against buffer D (pH = 6.8) containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 mM EDTA, 150 mM KCl and 0.1 mM DTT. The protein was then concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter device (Millipore) to a concentration of approximately 10 mg ml−1 (determined spectrophotometrically using the calculated extinction coefficient of 0.69 (mg ml−1 cm−1 at 280 nm) prior to size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex G75 16/60 column (Amersham) eluted with buffer D. The purified protein was then dialyzed for 16 h against buffer E (pH = 6.8) containing 30 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM KCl and 20 μM DTT. The protein was concentrated as above to a final concentration of 20 mg ml−1.

Crystallization and data collection

Crystals were obtained by the vapor diffusion method. To the purified and concentrated protein solution (20 mg mL−1) 10 mM of NADP and 5 mM of freshly prepared HMGSH were added and incubated on ice for at least 30 min. Equal volumes of this protein solution were mixed with a solution containing 17.5% PEG 3350 and 200 mM LiCl, and equilibrated as sitting drops over a reservoir of this solution. Large rectangular crystals of the ternary complex belonged to orthorhombic space group P212121 with cell parameters of a = 54.6 Å, b = 59.9 Å, and c = 88.0 Å and grew within two weeks. Single crystals were cryo-stabilized by rapid equilibration in a solution of 11.25% glycerol followed by flash freezing in a stream of nitrogen. Crystals of the ternary complex diffracted to 1.4 Å. Complete datasets were collected at 100 K with an ADSC Quantum 4 CCD detector system, using a wavelength of 1.11587 Å at the Advanced Light Source (ALS, Berkeley) beam line 8.3.1. The data set was processed and scaled using the HKL2000 program suite.14

Structure determination and refinement

The structure was solved by molecular replacement with AMoRe.15 Starting coordinates where taken from human carbonyl reductase 1 in complex with NADP and inhibitor hydroxy-PP (PDB accession code 1WMA).10 Crystallographic refinement to 1.54 Å and electron density maps calculation were carried out using Refmac.16 Configuration isomers of S-hydroxymethylglutathione were constructed and minimized with the MAB force field available in Moloc.17,18 Model building was done using Coot.19 Detailed data and refinement statistics are given in Table 1. Atomic coordinates for the human carbonyl reductase 1·BiGF2 complex structure have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank (accession code 2PFG). Figures were produced using PyMol 2002 (DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA, USA).

NMR characterization of BiGF2 in solution

Reduced glutathione (40 mM) was dissolved in D2O containing 150 mM K3PO4 to obtain a solution of pH 8.5. Paraformaldehyde or 13C labelled paraformaldehyde was dissolved in D2O at 160 mM concentration. Reactions were prepared by the addition of the requisite paraformaldehyde solution (0.6 ml) to NMR tubes each containing 0.3 ml of the glutathione solution. Reactions were allowed to equilibrate for a minimum of 3 h prior to data collection. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Inova-400 spectrophotometer at 399.57 and 100.47 MHz, respectively. High field 1H and COSY spectra were recorded on a Varian Inova-600 spectrophotometer at 599.67 MHz. DEPT-135 data allowed the degree of saturation to be assessed for each carbon.

1H NMR (599.67 MHz, D2O) δ 2.1 (m, 2H), 2.7 (ddd, J = 16.7, 9.5, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 3.1 (ddd, J = 13.7, 8.4, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 3.2 (dd, J = 15.5, 11.8 Hz, 1H), 3.5 (ddd, J = 5.9, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 3.5 (dd, J = 9.9, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 3.7 (s, 2H), 3.9 (ddd, J = 14.1, 1.1, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 4.2 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, 1H), 4.4 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 5.0 (dd, J = 15.8, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 5.0 (dd, J = 11.8, 6.0 Hz, 1H).

13C NMR (100.47 MHz, D2O) δ 25.5 (CH2), 34.8 (CH2), 36.0 (CH2), 44.8 (CH2), 61.2 (CH), 61.5 (CH2), 62.2 (CH2), 64.1 (CH), 173.3 (C), 178.0 (C), 179.1 (C), 181.3 (C).

pH Profile of glutathione–formaldehyde adducts

Reduced glutathione (40 mM) was dissolved in D2O containing 150 mM K3PO4. The pH of the solution was adjusted with HCl to yield solutions of pH 3, 6.5, 7.5, 8.0, and 8.5. 13C formaldehyde (160 mM) in D2O (0.6 ml) was added to 0.3 ml of each of the requisite glutathione solutions, and the reactions were allowed to equilibrate for at least 3 h prior to data collection. 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Inova-400 spectrophotometer at 100.47 MHz. Proportions of each constituent were assessed by integration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank those responsible for beamline 8.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Mark Kelly at the UCSF NMR facility for his assistance. We also thank Haridas Rode for careful review of the manuscript. This work was supported by an award to KMS from the Sandler Program for Asthma Research. Daniel Rauh was supported by funds from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Additional information regarding the hydroxymethylation of Cys121 by formaldehyde and supplementary figures (Fig. S1–Fig. S6). See DOI: 10.1039/b707602a

References

- 1.Tinguely JN, Wermuth B. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;260:9–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser R, Holmquist B, Vallee BL, Jornvall H. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8432–8438. doi: 10.1021/bi00447a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen DE, Belka GK, Du Bois GC. Biochem. J. 1998;331(Pt 2):659–668. doi: 10.1042/bj3310659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu L, Hausladen A, Zeng M, Que L, Heitman J, Stamler JS. Nature. 2001;410:490–494. doi: 10.1038/35068596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu L, Hausladen A, Zeng M, Que L, Heitman J, Stamler JS, Steverding D. Redox Rep. 2001;6:209–210. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moulis JM, Holmquist B, Vallee BL. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5743–5749. doi: 10.1021/bi00237a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Que LG, Liu L, Yan Y, Whitehead GS, Gavett SH, Schwartz DA, Stamler JS. Science. 2005;308:1618–1621. doi: 10.1126/science.1108228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naylor S, Mason RP, Sanders JK, Williams DH, Moneti G. Biochem. J. 1988;249:573–579. doi: 10.1042/bj2490573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mason RP, Sanders JK, Crawford A, Hunter BK. Biochemistry. 1986;25:4504–4507. doi: 10.1021/bi00364a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka M, Bateman R, Rauh D, Vaisberg E, Ramachandani S, Zhang C, Hansen KC, Burlingame AL, Trautman JK, Shokat KM, Adams CL. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nienaber VL, Richardson PL, Klighofer V, Bouska JJ, Giranda VL, Greer J. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:1105–1108. doi: 10.1038/80319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanghani PC, Stone CL, Ray BD, Pindel EV, Hurley TD, Bosron WF. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10720–10729. doi: 10.1021/bi9929711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macbeth MR, Schubert HL, Vandemark AP, Lingam AT, Hill CP, Bass BL. Science. 2005;309:1534–1539. doi: 10.1126/science.1113150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276A:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navaza J. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2001;57:1367–1372. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901012422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber PR. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 1998;12:37–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1007902804814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerber PR, Muller K. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 1995;9:251–268. doi: 10.1007/BF00124456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.