Abstract

Neurotensin (NT), a gut peptide, stimulates growth of colorectal cancers (CRCs) which possess the high affinity NT receptor (NTR1). Sodium butyrate (NaBT) is a potent histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) which induces growth arrest, differentiation and apoptosis of CRCs. Previously, we showed that NaBT increases nuclear GSK-3β expression and kinase activity; GSK-3β functions as a negative regulator of ERK signaling. The purpose of our current study was to determine: (a) whether HDACi alters NTR1 expression and function, and (b) the role of GSK-3β/ERK in NTR1 regulation. Human CRCs with NTR1 were treated with various HDACi and NTR1 expression and function were assessed. Treatment with HDACi dramatically decreased endogenous NTR1 mRNA, protein and promoter activity. Overexpression of GSK-3β decreased NTR1 promoter activity (> 30%); inhibition of GSK-3β increased NTR1 expression in CRC cells, indicating that GSK-3β is a negative regulator of ERK and NTR1. Consistent with our previous findings, HDACi significantly decreased phosphorylated ERK while increasing GSK-3β. Selective MEK/ERK inhibitors suppressed NTR1 mRNA expression in a time- and dose-dependent fashion, and reduced NTR1 promoter activity by ~70%. Finally, pretreatment with NaBT prevented NT-mediated COX-2 and c-myc expression and attenuated NT-induced IL-8 expression. HDACi suppresses endogenous NTR1 expression and function in CRC cell lines; this effect is mediated through, at least in part, the GSK-3β/ERK pathway. The down-regulation of NTR1 in CRCs may represent an important mechanism for the anti-cancer effects of HDACi.

Keywords: Neurotensin (NT), histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), GSK-3, ERK, colon cancer cells (CRC)

INTRODUCTION

Neurotensin (NT), a tridecapeptide synthesized by enteroendocrine cells (N cells) and potently released into the circulation following the ingestion of fats, is a growth factor for normal intestinal mucosa (1). Typical physiological functions for NT include stimulation of pancreatic and biliary secretions, inhibition of small bowel and gastric motility, and facilitation of fatty acid translocation (2–4). In addition to its trophic effects on normal gastrointestinal tissues, NT stimulates the proliferation, migration and invasion of various cancers bearing NT receptors (NTRs), including pancreatic, colorectal, prostate, lung and breast cancers (5–9). For example, Maoret et al (10) have demonstrated stimulation of the growth of multiple colorectal cancer cell lines (SW480, SW620, HT29 and HCT116) by NT acting through its high affinity receptor which is consistent with our previous findings as well (8, 9).

The effects of NT are mainly mediated by the high-affinity NTR1, a member of the G-protein coupled receptor family (11). NTR1 is expressed in a majority of colorectal cancers (CRCs) and many CRC cell lines (3, 12, 13). Signaling through NT/NTR1 stimulates various signal transduction pathways, including the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), ERK, JNK, RhoGTPase and focal adhesion kinase, among others, leading to the activation of various transcription factors and altering the expression of a number of tumor-promoting genes, such as COX-2 and IL-8 (14, 15). Our group has recently reported that NT stimulates IL-8 expression and CRC cell migration; this effect was predominantly through NTR1 and subsequent activation of Ca2+ dependent-PKC, NF-κB and MEK/ERK-dependent AP-1 activation (8). Therefore, it is important to characterize the regulation of NTR1 in human CRC cells, which may identify potential targets for therapeutic interventions.

The histone deacetylase (HDAC) family of transcriptional co-repressors has emerged as important regulators of intestinal cell differentiation and transformation. Expression of several HDAC isoforms are up-regulated in the majority of CRCs relative to adjacent normal mucosa, implicating a role of these HDACs in tumor promotion (16). Down-regulation of specific HDACs with pharmacological inhibitors leads to differentiation, growth arrest, and apoptosis of CRC cells in vitro and inhibits intestinal tumorigenesis in vivo (16–18). In addition to histones, HDACs have multiple protein substrates involved in the regulation of gene expression; inhibition of HDACs can also cause accumulation of acetylated forms of these proteins, altering their function (19). HDACi are also potent sensitizers for radiation therapy in multiple cell types including CRC cells (20). A number of HDACi, such as vorinostat, belinostat, entinostat and valproic acid, have or are presently being evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of various cancers including CRC (16, 18, 21). Despite increasing literature supporting a role for NTR1 in the development and progression of CRC, combined with emerging evidence for an important role of HDACi in the regression of CRCs, the relationship between HDACi and NTR1 expression has not been examined.

Sodium butyrate (NaBT) is a classic HDACi and a potent inducer of growth arrest, differentiation and apoptosis of CRC cells in vitro and in vivo; treatment with NaBT leads to decreased invasion and metastasis of CRC cells (22–24). Previously, we found that NaBT increased nuclear glycogen-synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) expression and activity, but decreased extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) in CRC cells (25, 26). Additionally, we reported that inhibition of GSK-3 significantly induced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in HT29 and Caco-2 cells, and increased the expression of COX-2 and IL-8, which are two important downstream targets of ERK1/2 activation, indicating that GSK-3β functions as a negative regulator of MAPK/ERK1/2 in CRC cells (24). We speculate that GSK-3β/ERK signaling may play an important role in HDACi-mediated cellular events, including gene regulation.

GSK-3 and ERK are critical downstream signaling proteins for the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and Ras/Raf/MEK-1 pathway, respectively, and regulate diverse cellular processes including embryonic development, cell differentiation and apoptosis. In our current study, we sought to determine the role of GSK-3/ERK1/2 signaling cascade on the regulation of NTR1 by HDACi in human CRC cells. Here, we show that HDACi suppresses endogenous NTR1 expression and function in NTR1-positive CRC cell lines. Additionally, we found that overexpression of GSK-3β decreased NTR1 promoter activity, while inhibition of GSK-3β increased NTR1 expression in CRC cells, indicating that GSK-3β is a negative regulator of ERK and NTR1. HDACi significantly decreased phosphorylated ERK; selective MEK/ERK inhibitors suppressed NTR1 mRNA expression in a time- and dose-dependent fashion. Our results suggest that HDACi alters NTR1 expression through, at least in part, the GSK-3β/ERK pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The GSK-3β inhibitor SB-216763 was purchased from Tocris (Ellisville, MO). Protein synthesis inhibitors cycloheximide and anisomycin were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Non-targeting control siRNA SMARTpool and the SMARTpool for GSK-3α and GSK-3β were purchased from Dhamacon Inc. (Lafayette, CO). 32P-UTP (3000 Ci/mmol) was from PerKinElmer (Boston, MA). The GSK-3β overexpression plasmid was a kind gift from Dr. James Woodgett (Toronto, Canada). The human NTR1 promoter-luciferase reporter plasmid was a gift from Dr. Patricia Forgez (Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France). The CCK (A) and CCK (B) receptor plasmids were gifts from Dr. Mark Hellmich (Galveston, TX). Ultraspec RNA reagent for RNA isolation was from Biotecx Laboratories (Houston, TX). Formaldehyde loading dye, positively charged nylon membranes, T7/SP6 MAXIscript labeling kit and RPA III Ribonuclease Protection kit were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). The hCK-5 multi-probe template set was purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-human NTR1 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Uo126 and the dual luciferase assay system were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). Cell lysis buffer (10X), rabbit antiphosphorylated ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Lipofectamine Plus and NuPAGE bis-Tris gel were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Other reagents were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA).

Cell culture

Human CRC cell lines HCT116, HT29, SW480 and SW620 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). HT29 and HCT116 were maintained in McCoy´s 5A supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum (FBS). SW480 and SW620 were maintained in DMEM/Leibovitz (1:1) supplemented with 10% FBS. The human colon cancer cell line KM20 was obtained from Dr. Isaiah Fidler (M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX) and grown in minimum Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10 ml/L of sodium pyruvate, 10 ml/L of non-essential amino acids, 20 ml/L of minimum Eagle’s medium essential vitamin mixture, and 10% FBS.

Northern blot

RNA was isolated from cultured cells using Ultraspec RNA reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA (35 µg) was dissolved in formaldehyde loading dye, resolved on a 1.2% agarose/formaldehyde gel, and transferred to positively charged nylon membranes. After baking in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 2 h, membranes were pre-hybridized in hybridization buffer at 65°C for 2 h, then incubated for 8–12 h with a 32P-UTP labeled cRNA probe containing 1087 bp (471/1558 from start site) of human NTR1 cDNA subcloned into the XhoI/SmaI sites of the pGEM-7zf vector, or a labeled cRNA probe of human COX-2 (8), or a labeled cRNA probe of human c-myc (a gift from Dr. Brad Thompson, Galveston, TX) utilizing the T7/SP6 MAXIscript labeling kit. Membranes were then washed in 2X SSC (1X SSC= 0.15 M NaCl , 0.015 M Na citrate, 0.1% SDS) at room temperature, followed by two washes in 0.1XSSC at 65°C for 1 h. Results were detected by autoradiography. All membranes were re-probed with GAPDH as an internal control.

RNase protection assay

RNA was isolated from cultured cells as described above. A 32P-UTP labeled antisense RNA probe was prepared using the hCK-5 multi-probe template set and T7SP6 MAXIscript kit. RNase protection assays were performed using labeled probes and the RPA III Ribonuclease Protection Kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, and as we have described previously (8, 27). Finally, samples were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 5% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and detected by autoradiography.

Transient transfection and luciferase assay

HCT116 or SW480 cells were seeded in 24-well plates one day prior to transfection. Cells were transfected with 1µg NTR1 promoter-luciferase plasmid with or without 1 µg of GSK-3 expression plasmids or HDAC expression vectors (28) and 20 ng pRL-TK (internal control) using Lipofectamine Plus; 24 h following transfection, cells were treated with or without reagents for various times and harvested for analysis. Luciferase was assayed with the dual luciferase assay system, as previously described (29). Transfection efficiency was corrected using Renilla luciferase activity. Transient transfection of siRNA was performed by electroporation (300V, 400 µfarads) using the GenePulser XCell (Bio-Rad) as previously described (1).

Protein preparation and Western blotting assay

Protein preparation and Western blotting were performed as described previously (2). In brief, cells were lysed with 1X cell lysis buffer. Equal amounts of protein were resolved on NuPAGE bis-Tris gel and electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies in TBST followed by a horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h. Membranes were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Heathcare).

Statistical analysis

The luciferase activity, measured in experiments where only two treatment groups were used (Fig. 1D, Fig. 4C and Fig. 5C), was analyzed using the two-sample t test. Luciferase activity measured in an experiment with 5 treatment groups (vector and 4 HDACs; Fig. 2D) was analyzed using one-way classification analysis of variance. All tests were assessed at the 0.05 level of significance. All statistical computations were conducted using the SAS® system, Release 9.1 (30).

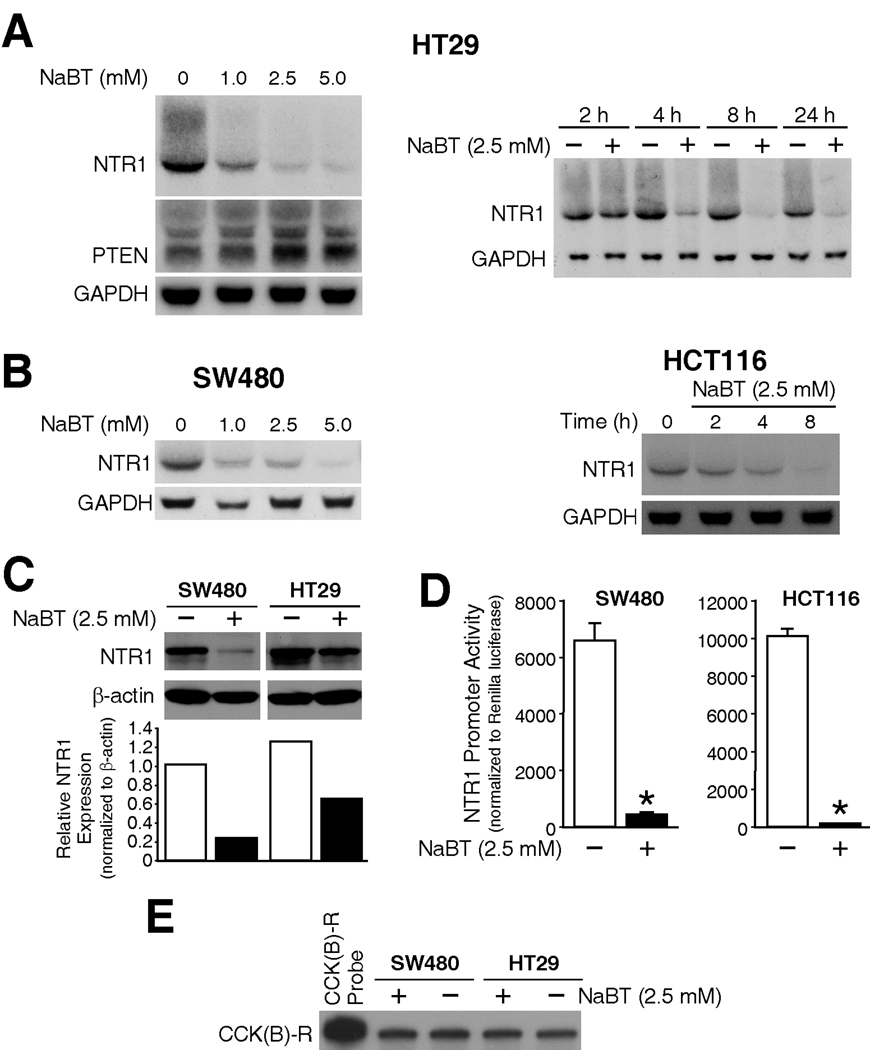

Figure 1. NaBT down-regulated NTR1 expression in colon cancer cell lines.

A) Human CRC cells HT29 were treated with various concentrations of NaBT or vehicle (PBS) (lanes 1–4), or with 2.5 mM of NaBT over a time course or vehicle (PBS) (lanes 5–12). Total RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blots using hNTR1 cRNA probe. Membranes were then reprobed with hPTEN and GAPDH. B) SW480 and HCT116 cells were treated with various concentrations of NaBT and harvested at 20h, or treated with 2.5 mM NaBT over a time course. RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blots using hNTR1 and GAPDH probes. C) SW480 and HCT116 cells were treated with 2.5 mM of NaBT, or PBS (vehicle) for 18 h. Total protein was extracted and analyzed by Western blots using anti-human NTR1 antibody, the membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody as internal control. NTR1 signals were quantitated densitometrically and expressed with respect to β-actin. D) SW480 and HCT116 cells were transiently transfected with the hNTR1 promoter plasmid and Renilla-luciferase vector (pRL-TK). After 24h transfection, cells were treated with 2.5 mM of NaBT or PBS for another 20 h, then harvested and luciferase activity was measured (A representative experiment is shown from three separate experiments utilizing at least 3 wells/constructs). Data was corrected by Renilla luciferase activity. E) HT29 and SW480 cells were treated with 2.5 mM of NaBT for 20 h, RNA was extracted and analyzed by RNase protection with CCK (B) receptor probe producing a 410 bp of protected band.

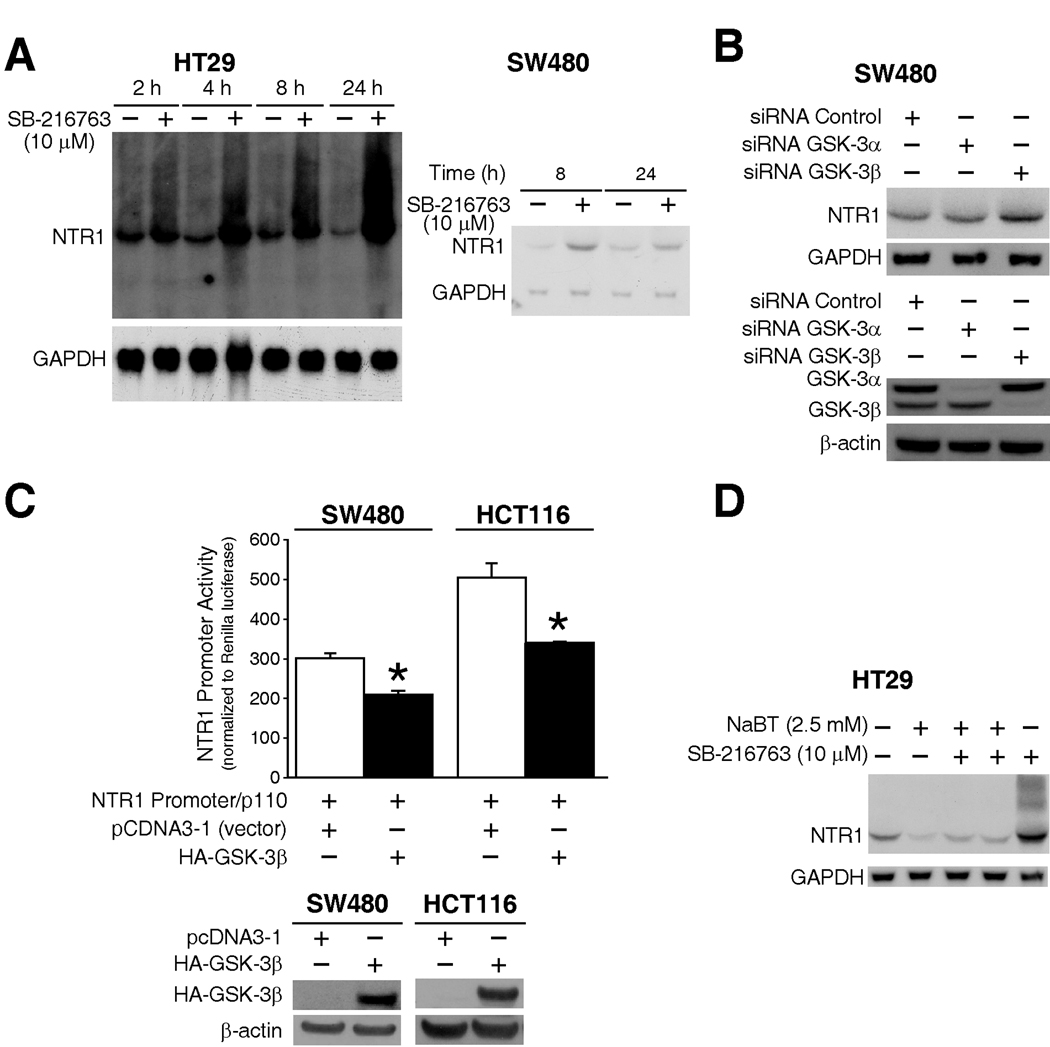

Figure 4. The role of GSK-3β in NTR1 regulation by NaBT.

A) HT29 and SW480 cells were treated with GSK-3β inhibitor SB-216763 or vehicle (DMSO) over a time course, and RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blots using hNTR1 and GAPDH probes. B) SW480 cells were transfected with GSK-3α or GSK-3β siRNA or control siRNA (Representative of three independent experiments). RNA and was isolated and analyzed by Northern blots for NTR1 mRNA expression. Whole proteins were extracted and knockdown of GSK-3α and GSK-3β was confirmed by Western blotting using anti-GSK-3α/β. C) SW480 and HCT116 cells were co-transfected with NTR1 promoter plasmid and HA-GSK-3β over-expression plasmid or empty vector (pCDNA3.1); 40 h after transfection, cells were harvested and luciferase activity measured (Representative experiment shown from three separate experiments utilizing at least 3 wells/construct). The overexpression of HA-tagged GSK-3β was confirmed by Western blotting using anti-HA antibody. D) HT29 cells was pre-treated with SB-216763 or DMSO for 30 min followed by combination treatment with NaBT or vehicle (PBS) for an additional 6 h, RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blots using hNTR1 and GAPDH probes.

Figure 5. The role of MEK/ERK pathway for NTR1 regulation by HDACi/GSK-3 signaling.

A) HT29 cells was treated with vehicle DMSO or MEK/ERK inhibitor Uo126 (5 µM) for various times, and different concentrations for 16h, RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blots using hNTR1 and GAPDH probes. B) HCT116 cells were treated with MEK/ERK1 inhibitors Uo126 (0.5, 5 µM), PD98059 (20 µM), p38 inhibitor SB-203580 (10 µM) or vehicle DMSO for 16 h; SW480 cells was treated with 1 µM or 5 µM of Uo126 for 16 h, RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blots using hNTR1 and GAPDH probes. C) SW480 cells were transfected with the NTR1 promoter plasmid, after 24 h, cells were treated with Uo126 (5 µM) for another 16 h, then harvested and luciferase activity was measured (A representative experiment is shown from three separate experiments utilizing at least 3 wells/construct). D) HCT116 and SW480 cells were treated with vehicle DMSO, 2.5 mM of NaBT, 1 µM of apicidin and 20 µM of Emodin (as control) for 18 h, total protein was extracted and analyzed by Western blots using p-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 antibodies. pERK1/2 signals were quantitated densitometrically and expressed with respect to total ERK1/2.

Figure 2. NTR1 mRNA is suppressed by multiple HDACi.

Entinostat, valproic acid, apicidin and TSA, all HDACi or vehicle (DMSO) were used for treating CRC cells HT29 (A), and HCT116 (B). Total RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blots using hNTR1 cRNA and GAPDH probes.

RESULTS

NaBT down-regulates NTR1 expression in CRC cell lines

To examine the role of NaBT, a potent HDAC inhibitor, on the expression of NTR1 in colon cancer cell lines, HT29 cells were treated with different dosages of NaBT; NTR1 expression was then examined over a time course following treatment of cells with NaBT (2.5 mM). We found that NaBT inhibited NTR1 mRNA expression in HT29 cells in both a dose- and time-dependent fashion (Fig.1A). As a control for the effect of NaBT, the blot was stripped and reprobed for PTEN expression, and similar to our previous findings (23), NaBT increased PTEN expression; the blots were reprobed with GAPDH to assess loading equality. We further confirmed that NaBT inhibited NTR1 expression in other NTR1-positive cell lines, including SW480, HCT116 (Fig.1B), and SW620, KM20 (data not shown).

To further confirm the downregulation of NTR1 expression by NaBT, we next assessed the effect of NaBT on NTR1 protein expression by Western blot (Fig.1C). Treatment with NaBT decreased NTR1 protein expression in both SW480 and HT29 cells. Finally, to assess whether the effects of NaBT are through regulation of gene transcription, SW480 and HCT116 cells were transiently transfected with the NTR1 promoter-luciferase plasmid and Renilla-luciferase plasmid (as an internal control) (Fig.1D). NaBT dramatically decreased NTR1 promoter activity, suggesting transcriptional regulation. Interestingly, as noted by RNase protection assays, NaBT treatment did not affect mRNA expression of other gastrointestinal hormone receptors, such as the cholecystokinin-B receptor (Fig.1E), CCK-A receptor and gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (data not shown).

NTR1 expression is inhibited by multiple HDAC inhibitors

To confirm that NaBT inhibits NTR1 mRNA through inhibition of HDAC, Trichostatin A (TSA), valproic acid, entinostat, and apicidin, all structurally distinct HDACi compounds, were tested. These inhibitors suppressed NTR1 in all NTR1-positive cell lines tested, including HT29 and HCT116 (Fig. 2A, B), SW480, SW620 and KM20 (data not shown).

We did not detect any appreciable decrease of NTR1 mRNA expression using HDAC1, 2, or 3 siRNA transfected into SW480, HCT116 and HT29 cells (data not shown). One possible explanation for the absence of an effect by the siRNA may be due to the fact that other HDAC isoforms are present, which then substitute for the absence of one isoform as we have previously noted with knock-down of HDAC3 leading to HDAC2 activation in CRC cells (QD Wang, unpublished data).

NTR1 may be a direct target gene of HDACi

HDACi-regulated genes can be separated into direct and indirect targets (16). Direct targets, such as p21waf1, are altered within a few hours of HDACi treatment, occurring despite the presence of protein synthesis inhibitors (31). We have previously noted that, after treatment with NaBT for 4h, the expression of NTR1 is significantly reduced, suggesting that NTR1 may be a direct target of HDACi (31). To confirm this finding, we next treated HT29 cells with the HDACi TSA and apicidin and harvested cells at a different time points. Treatment with both TSA and apicidin for 4h led to significantly decreased NTR1 mRNA expression (Fig. 3A). These results were confirmed using SW620 cells (Fig. 3B). Next, treatment of HT29 cells with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, in combination with either NaBT or apicidin, minimally altered the effects of HDACi treatment (Fig. 3C); similar results were noted with anisomycin, another protein synthesis inhibitor. Taken together, these results indicate that NTR1 may be a direct target gene for HDACi.

Figure 3. Direct effects of HDACi on NTR1 expression.

HT29 and SW620 cells were treated with HDACi TSA, apicidin or vehicle (DMSO) over a time course (A,B), HT29 cells was treated with NaBT or apicidin alone or in combination with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide or anisomycin for 6 h (C), RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blots using hNTR1 and GAPDH probes.

The negative role of GSK-3β in NTR1 regulation by NaBT

Protein synthesis inhibitors minimally altered the effects of HDACi treatment, suggesting that other factors may be involved in NTR1 regulation. It has been reported that NTR1 mRNA is increased by LiCl, a non-specific inhibitor of GSK-3β, in breast cancer cells (32). Previously, we showed that nuclear GSK-3β expression and kinase activity were increased by treatment with NaBT and other HDACi (26). Because GSK-3 plays an important role in the growth and differentiation of cancer cells, we next determined if GSK-3β is involved in NTR1 regulation. We first treated HT29 and SW480 cells with the selective GSK-3β inhibitor SB-216763, and examined NTR1 mRNA expression over a time course. Treatment with SB-216763 significantly upregulated NTR1 mRNA expression in both cell lines (Fig. 4A). SW480 cells were then transfected with GSK-3α siRNA, GSK-3β siRNA or control siRNA and analyzed by Northern blot assay. GSK-3β siRNA, but not GSK-3α siRNA, increased NTR1 expression (Fig. 4B), indicating that GSK-3β negatively regulates NTR1. To confirm these results, the NTR1 promoter plasmid was cotransfected with the GSK-3β overexpressing plasmid in both SW480 and HCT116 cell lines. Overexpression of GSK-3β decreased NTR1 promoter activity by greater than 30% (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, treatment with the GSK-3β inhibitor SB-216763 partially attenuated the NTR1 mRNA suppression resulting from NaBT treatment (Fig.4D). Taken together, these results suggest that GSK-3β is involved, at least in part, in NTR1 regulation by NaBT.

The MAPK/ERK pathway is required for NTR1 regulation by HDACi/GSK-3β signaling

We have previously reported that GSK-3β functions as a negative regulator of ERK in NTR1-positive HT29 cells and NTR1-negative Caco-2 cells (24), and NaBT decreases ERK activity in Caco-2 cells (25) suggesting that HDACi may increase GSK-3β activity, subsequently suppressing ERK in NTR1-positive CRC cells. We propose that this alteration of GSK-3β/ERK signaling may be involved in NTR1 regulation by HDACi.

To investigate this supposition, HT29, SW480, and HCT116 cells were treated with the selective MEK/ERK inhibitor Uo126, and NTR1 expression was analyzed by Northern blot. Treatment with Uo126 suppressed NTR1 mRNA expression in a time- and dose-dependent fashion in HT29 cells (Fig. 5A); similar results were noted with SW480 and HCT116 cells studies (Fig. 5B), as well as SW620 and KM20 cells (data not shown). We confirmed these results by treating cells with another MEK/ERK inhibitor, PD98059; the results were identical to those using Uo126. In contrast, treatment with a selective p38 inhibitor, SB-203580, did not affect NTR1 expression (Fig. 5B). Next, SW480 cells were transfected with the NTR1 promoter-luciferase plasmid; after 24 h transfection, cells were treated with Uo126 (5 µM) for another 16 h (Fig. 5C). Treatment with the MEK/ERK inhibitor Uo126 resulted in an approximately 70% decrease in NTR1 promoter activity in SW480 cells (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that the MEK/ERK pathway is necessary for NTR1 mRNA expression.

To confirm that the MEK/ERK pathway is regulated by HDACi/GSK-3β signaling, which subsequently affects NTR1 expression in NTR-positive CRC cells, we next assessed the effects of NaBT and apicidin on ERK1/2 protein expression in SW480 and HCT116 cells by Western blot (Fig. 5D). Treatment with NaBT and apicidin significantly decreased phospho-ERK1/2 levels in both SW480 and HCT116 cells; in contrast, emodin, which is an inhibitor of protein kinase CK2, did not affect ERK1/2 levels. Collectively, these results indicate that the MEK/ERK pathway is regulated, at least in part, by HDACi/GSK-3β, and subsequently alters NTR1 expression.

NaBT attenuates NT-induced hCOX-2, c-myc and IL-8 expression

We next determined the effects of NaBT treatment on NT-mediated gene expression in CRC cells. NT increases the expression of IL-8, COX-2 (8, 33), and c-myc (Fig. 6A), all of which contribute to colon cancer cell growth and metastasis (8, 16, 24). To evaluate the effects of NaBT on NT-induced cellular events, HT29 and HC116 cells were pretreated with NaBT for 6 h, then incubated with NT over a time course. As shown in Fig. 6A, NT increased c-myc expression in time-dependent fashion; NaBT prevented NT-stimulated c-myc induction. Pretreatment with NaBT blocked NT-induced COX-2 (Fig. 6B) and IL-8 (Fig. 6C) expression in HT29 and HCT116 cells, respectively. Interestingly, NaBT alone slightly increased IL-8 expression in HCT116 cells, which has been reported in other cells (34, 35). Collectively, these results indicate that HDACi, such as NaBT, are important regulators for NT/NTR1 signaling; this effect appears to be predominantly through the suppression of NTR1 expression.

Figure 6. The effects of HDACi on NT-mediated genes.

HCT116 and HT29 cells were starved in serum free medium for 24 h, then treated with NaBT (2.5 mM) for 6 h followed by combination treatment with 100 nM of NT or vehicle PBS for an additional 0.5 h, 1 h and 2 h. Total RNA was isolated and analyzed by Northern blots using a c-myc probe (A), or hCOX-2 probe (B), or analyzed by RNase protection assay using hCK-5 probe set (C).

DISCUSSION

The chemotherapeutic potential of HDACi, including a number of dietary factors with HDAC inhibitory activity and anti-tumor effects in the colon, has been extensively described (36). Based upon these pre-clinical findings, several HDACi are currently being evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of a variety of hematological and solid tumors including CRCs (18). In our present study, the effect of HDACi on NTR1 gene expression was determined. NaBT and other HDACi suppressed endogenous NTR1 expression in all NTR1-positive CRC cell lines examined through, at least in part, the GSK-3β/ERK pathway. Furthermore, NaBT prevented NT-mediated induction of genes (ie, c-myc, COX-2 and IL-8), which can promote CRC proliferation and invasion.

The effects of various hormones on tumor growth are well-established. For example, altering hormone levels or blocking ligand binding to receptors has become part of the adjuvant treatment strategy for certain breast and prostate cancers (3, 7, 37). Similarly, cancers can also express receptors for gastrointestinal hormones which can alter the growth of these receptor-positive cancers. Studies from our laboratory and others have shown that ~50% of CRCs possess NTR1 (12). HDACi suppress NTR1 while we did not detect decreases in the expression of CCK (A) or CCK (B) receptors or gastrin-releasing peptide receptor in the CRCs examined. The importance of NTR1 on CRCs has been clearly delineated (3, 32); however, the significance of CCK and GRP receptors in CRC proliferation and prognosis is more controversial (38). Together, The effect of HDACi on NTR1 expression may reflect the importance of NTR1 on CRC proliferation and may also represent an important mechanism for the anti-cancer effects of HDACi.

Mechanisms of HDACi on gene regulation involve both direct and/or indirect effects (16). The findings in our current study suggest that the effects of HDACi on NTR1 are likely through both direct and indirect mechanisms. The indirect effects of HDACi-mediated gene regulation involve many different pathways and factors. For example, HDACi can alter expression patterns through effects on signal transduction pathways, notably, the PI3K and MEK/ERK pathways (39, 40). In our current study, we found that inhibition of GSK-3β led to increased expression of NTR1 mRNA in CRC cells; overexpression of GSK-3β led to a decrease in NTR1 promoter activity, suggesting that GSK-3β is a negative regulator of ERK and NTR1. We next confirmed that treatment with MEK/ERK inhibitors Uo126 and PD98059 suppressed NTR1 expression and promoter activity in CRC cell lines. Treatment with NaBT and apicidin significantly reduced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in NTR1 positive CRC cells, which is consistent with findings by Tatebe et al. (41), showing that treatment of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells with the HDACi valproic acid led to decreased activation of ERK.

GSK-3 is an evolutionarily conserved signaling molecule that plays an important role in diverse biologic processes (42). More recent studies indicate a role for GSK-3 in the control of cell proliferation and survival in mammalian cells and in the identification of GSK-3 as a component of the Wnt signaling pathway, which controls development in invertebrates and vertebrates (43, 44). Several kinases have been shown to phosphorylate GSK-3 inhibitory sites in vitro (42). For example, protein kinase B (PKB/Akt), a serine/threonine kinase located downstream of PI3K, phosphorylates these sites in vitro and in vivo (45), and certain PKC isoforms have been shown to phosphorylate and inactivate both isoforms of GSK-3 (46). These findings suggest that GSK-3 represents an important convergence point that integrates signals from multiple signaling cascades. Therefore, the regulation of NTR1 by GSK-3 signaling suggested that additional signaling pathways and/or factors may be involved in NTR1 regulation by HDACi. Indeed, it has been reported that the NTR1 promoter is activated by the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in Cos-7 cells, and NTR1 mRNA is up-regulated by LiCl, a non-specific inhibitor of GSK-3β, in human breast epithelial cells (32). Together, our results indicate that the HDAC/GSK-3β/ERK signaling cascade is involved in NTR1 regulation in CRC cells.

NT/NTR signaling contributes to tumorigenesis, cancer cell migration and metastasis, likely through the induction of downstream of proteins which mediate these effects (5, 32, 37). We next evaluated the effect of NTR1 suppression by HDACi on NT-induced cancer-promoting genes. COX-2, the rate-limiting enzyme for prostaglandin synthesis, plays a critical role in the inflammatory response and in colon tumorigenesis (47). COX-2 expression is induced by a numbers of factors, including NT and other hormones (33). From our results, HDACi suppressed NTR1 expression and significantly inhibited NT-induced COX-2 expression in HT29 cells, suggesting that this effect is mediated through NTR1 inhibition. In addition to COX-2, we found that treatment with HDACi attenuated NT-stimulated IL-8 expression. IL-8, a potent chemotactic factor, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases (48) and in the growth of CRCs as an autocrine growth factor (49). The expression of IL-8 is regulated by numerous factors and pathways. Pretreatment with NaBT significantly attenuated NT-stimulated IL-8 expression, suggesting this inhibitory effect is mediated through NTR1 suppression by HDACi. Next, c-myc has been reported to be commonly up-regulated in certain human cancers, leading to cell proliferation, arrested differentiation, and malignant transformation (50). Our data showed that NT increased c-myc expression in HCT116 cells; NaBT decreased basal c-myc expression and blocked NT-stimulated-c-myc activity. Taken together, our results indicate the significant inhibitory role of HDACi in NT-induced expression of cancer-promoting genes.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate, for the first time, that HDACi suppresses endogenous NTR1 expression and function in CRC cell lines. Additionally, HDACi blocks NT-mediated COX-2 and c-myc expression and attenuates NT-mediated IL-8 expression. The downregulation of NTR1 may represent a possible mechanism for the anti-cancer effects of HDACi in CRCs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Karen Martin for manuscript preparation, Hung Doan for technical assistance, and Tatsuo Uchida for statistical analysis.

This work was supported by grants R37AG010885, RO1CA104748, RO1DK48498, and P20CA127004 (GI SPORE) from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CRCs

colorectal cancers

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GSK-3β

glycogen-synthase kinase-3β

- HDACi

histone deacetylase inhibitor

- MAPKs

mitogen-activated protein kinases

- NaBT

sodium butyrate

- NT

neurotensin

- NTR

NT receptor

- NTR1

NT receptor type 1

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- TSA

Trichostatin

Footnotes

This paper was presented, in part, at the Digestive Disease Week meeting in Chicago, IL (May 30 – June 4, 2009).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferris CF, Carraway RE, Hammer RA, Leeman SE. Release and degradation of neurotensin during perfusion of rat small intestine with lipid. Regul Pept. 1985;12:101–111. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(85)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung DH, Evers BM, Shimoda I, Townsend CM, Jr, Rajaraman S, Thompson JC. Effect of neurotensin on gut mucosal growth in rats with jejunal and ileal Thiry-Vella fistulas. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1254–1259. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91512-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evers BM. Neurotensin and growth of normal and neoplastic tissues. Peptides. 2006;27:2424–2433. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evers BM, Izukura M, Townsend CM, Jr, Uchida T, Thompson JC. Differential effects of gut hormones on pancreatic and intestinal growth during administration of an elemental diet. Ann Surg. 1990;211:630–636. discussion 6–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dupouy S, Viardot-Foucault V, Alifano M, et al. The neurotensin receptor-1 pathway contributes to human ductal breast cancer progression. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwase K, Evers BM, Hellmich MR, et al. Inhibition of neurotensin-induced pancreatic carcinoma growth by a nonpeptide neurotensin receptor antagonist, SR48692. Cancer. 1997;79:1787–1793. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970501)79:9<1787::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas RP, Hellmich MR, Townsend CM, Jr, Evers BM. Role of gastrointestinal hormones in the proliferation of normal and neoplastic tissues. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:571–599. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Wang Q, Ives KL, Evers BM. Curcumin inhibits neurotensin-mediated interleukin-8 production and migration of HCT116 human colon cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5346–5355. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshinaga K, Evers BM, Izukura M, et al. Neurotensin stimulates growth of colon cancer. Surg Oncol. 1992;1:127–134. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(92)90025-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maoret JJ, Anini Y, Rouyer-Fessard C, Gully D, Laburthe M. Neurotensin and a non-peptide neurotensin receptor antagonist control human colon cancer cell growth in cell culture and in cells xenografted into nude mice. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:448–454. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990129)80:3<448::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Najimi M, Maloteaux JM, Hermans E. Cytoskeleton-related trafficking of the EAAC1 glutamate transporter after activation of the G(q/11)-coupled neurotensin receptor NTS1. FEBS Lett. 2002;523:224–228. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chao C, Tallman ML, Ives KL, Townsend CM, Jr, Hellmich MR. Gastrointestinal hormone receptors in primary human colorectal carcinomas. J Surg Res. 2005;129:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maoret JJ, Pospai D, Rouyer-Fessard C, et al. Neurotensin receptor and its mRNA are expressed in many human colon cancer cell lines but not in normal colonic epithelium: binding studies and RT-PCR experiments. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:465–471. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehlers RA, Zhang Y, Hellmich MR, Evers BM. Neurotensin-mediated activation of MAPK pathways and AP-1 binding in the human pancreatic cancer cell line, MIA PaCa-2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:704–708. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassan S, Dobner PR, Carraway RE. Involvement of MAP-kinase, PI3-kinase and EGF-receptor in the stimulatory effect of Neurotensin on DNA synthesis in PC3 cells. Regul Pept. 2004;120:155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mariadason JM. HDACs and HDAC inhibitors in colon cancer. Epigenetics. 2008;3:28–37. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.1.5736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glauben R, Sonnenberg E, Zeitz M, Siegmund B. HDAC inhibitors in models of inflammation-related tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 2009;280:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnstone RW. Histone-deacetylase inhibitors: novel drugs for the treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:287–299. doi: 10.1038/nrd772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu WS, Parmigiani RB, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: molecular mechanisms of action. Oncogene. 2007;26:5541–5552. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karagiannis TC, El-Osta A. Modulation of cellular radiation responses by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2006;25:3885–3893. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson CL, Laniel MA. Histones and histone modifications. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R546–R551. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim YS, Tsao D, Siddiqui B, et al. Effects of sodium butyrate and dimethylsulfoxide on biochemical properties of human colon cancer cells. Cancer. 1980;45:1185–1192. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800315)45:5+<1185::aid-cncr2820451324>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Q, Zhou Y, Wang X, Chung DH, Evers BM. Regulation of PTEN expression in intestinal epithelial cells by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation and nuclear factor-kappaB inhibition. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7773–7781. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Q, Zhou Y, Wang X, Evers BM. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is a negative regulator of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Oncogene. 2006;25:43–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding Q, Wang Q, Evers BM. Alterations of MAPK activities associated with intestinal cell differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:282–288. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Q, Zhou Y, Wang X, Evers BM. p27 Kip1 nuclear localization and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitory activity are regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 in human colon cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:908–919. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q, Wang X, Evers BM. Induction of cIAP-2 in human colon cancer cells through PKC delta/NF-kappa B. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51091–51099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans PM, Zhang W, Chen X, Yang J, Bhakat KK, Liu C. Kruppel-like factor 4 is acetylated by p300 and regulates gene transcription via modulation of histone acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33994–34002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, Ji Y, Wang X, Evers BM. Isolation and molecular characterization of the 5'-upstream region of the human TRAIL gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:466–471. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.R1. SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 9.1 User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Archer SY, Meng S, Shei A, Hodin RA. p21(WAF1) is required for butyrate-mediated growth inhibition of human colon cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6791–6796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Souaze F, Viardot-Foucault V, Roullet N, et al. Neurotensin receptor 1 gene activation by the Tcf/beta-catenin pathway is an early event in human colonic adenomas. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:708–716. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brun P, Mastrotto C, Beggiao E, et al. Neuropeptide neurotensin stimulates intestinal wound healing following chronic intestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G621–G629. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00140.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chavey C, Muhlbauer M, Bossard C, et al. Interleukin-8 expression is regulated by histone deacetylases through the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in breast cancer. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1359–1366. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.047332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim YK, Lee EK, Kang JK, et al. Activation of NF-kappaB by HDAC inhibitor apicidin through Sp1-dependent de novo protein synthesis: its implication for resistance to apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:2033–2041. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dashwood RH, Ho E. Dietary histone deacetylase inhibitors: from cells to mice to man. Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sehgal I, Powers S, Huntley B, Powis G, Pittelkow M, Maihle NJ. Neurotensin is an autocrine trophic factor stimulated by androgen withdrawal in human prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4673–4677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rivera CA, Ahlberg NC, Taglia L, Kumar M, Blunier A, Benya RV. Expression of GRP and its receptor is associated with improved survival in patients with colon cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10585-009-9265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim YK, Seo DW, Kang DW, Lee HY, Han JW, Kim SN. Involvement of HDAC1 and the PI3K/PKC signaling pathways in NF-kappaB activation by the HDAC inhibitor apicidin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347:1088–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schauber J, Iffland K, Frisch S, et al. Histone-deacetylase inhibitors induce the cathelicidin LL-37 in gastrointestinal cells. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:847–854. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tatebe H, Shimizu M, Shirakami Y, et al. Acyclic retinoid synergises with valproic acid to inhibit growth in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1175–1186. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui H, Meng Y, Bulleit RF. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta activity regulates proliferation of cultured cerebellar granule cells. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;111:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korswagen HC, Coudreuse DY, Betist MC, van de Water S, Zivkovic D, Clevers HC. The Axin-like protein PRY-1 is a negative regulator of a canonical Wnt pathway in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1291–1302. doi: 10.1101/gad.981802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378:785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang X, Yu S, Tanyi JL, Lu Y, Woodgett JR, Mills GB. Convergence of multiple signaling cascades at glycogen synthase kinase 3: Edg receptor-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation by lysophosphatidic acid through a protein kinase C-dependent intracellular pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2099–2110. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2099-2110.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Claria J. Cyclooxygenase-2 biology. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:2177–2190. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papadakis KA, Targan SR. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:289–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brew R, Erikson JS, West DC, Kinsella AR, Slavin J, Christmas SE. Interleukin-8 as an autocrine growth factor for human colon carcinoma cells in vitro. Cytokine. 2000;12:78–85. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pelengaris S, Khan M, Evan G. c-MYC: more than just a matter of life and death. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:764–776. doi: 10.1038/nrc904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]