Abstract

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI can detect low-concentration compounds with exchangeable protons through saturation transfer to water. CEST imaging is generally slow, as it requires acquisition of saturation images at multiple frequencies. In addition, multi-slice imaging is complicated by saturation effects differing from slice to slice because of relaxation losses. In this study, a fast three-dimensional (3D) CEST imaging sequence is presented that allows whole-brain coverage for a frequency-dependent saturation spectrum (z-spectrum, 26 frequencies) in less than 10 min. The approach employs a 3D gradient- and spin-echo (GRASE) readout using a prototype 32-channel phased-array coil, combined with two-dimensional SENSE accelerations. Results from a homogenous protein-containing phantom at 3T show that the sequence produced a uniform contrast across all slices. To show translational feasibility, scans were also performed on five healthy human subjects. Results for CEST images at 3.5ppm downfield of the water resonance, so-called amide proton transfer (APT) images, show that lipid signals are sufficiently suppressed and artifacts caused by B0 inhomogeneity can be removed in post-processing. The scan time and image quality of these in vivo results show that 3D CEST MRI using GRASE acquisition is feasible for whole-brain CEST studies at 3T in a clinical time frame.

Keywords: CEST, APT, 3D, GRASE, SENSE, whole brain, lipid artifact

Introduction

Recently, a new magnetization transfer (MT)-based contrast mechanism for MRI, called chemical exchange-dependent saturation transfer (CEST) (1–4), has emerged in the field of cellular and molecular imaging. This contrast is generated by saturation labeling of the exchangeable protons of a solute, followed by a physical transfer (chemical exchange) of saturated magnetization from the labeled protons to water protons, resulting in a decrease in the magnetization of bulk water protons. Even low-concentration (micromolar or millimolar range) solutes can cause a detectable cumulative effect on the water if the protons have a suitable exchange rate, and the labeling process is sustained by sufficiently long saturation. Currently, most CEST studies involve the development of diamagnetic and paramagnetic contrast agents in phantoms (5–8) or animal models (9–12), but several endogenous CEST approaches for humans have also been reported. These include urea detection in the kidney (13), amide proton transfer (APT) imaging of mobile proteins and peptides in the brain and brain tumors (14–17), glycoCEST imaging of glycogen in muscle (18), and gagCEST for detecting glycosaminoglycans in the knee (19).

Ultimately, the goal is to develop CEST imaging methodology suitable for use in the clinical setting, where technical issues relate to power deposition (increasing quadratically with field strength), field inhomogeneity, and fast acquisition of multiple saturation frequencies (z-spectrum) over a large volume have to be addressed. When using echo-planar type readout gradients, lipid artifacts may interfere with APT imaging (20). Until now, to our knowledge, volumetric CEST imaging has been limited to 5 slices in animals at 4.7T (21) and humans at 1.5T (22), which were acquired with multi-slice protocols. Recently, three-dimensional (3D) gradient- and spin-echo (GRASE) image acquisition has been successfully implemented for arterial spin labeling (ASL) (23) and vascular space occupancy (VASO) MRI (24). In this study, a fast 3D GRASE approach for whole brain CEST imaging (with an emphasis on APT imaging) is presented. The nature of 3D image acquisition permits two-dimensional (2D) sensitivity encoding (SENSE) accelerations in both right-left (RL) and superior-inferior (SI) phase-encoding directions, which is realized here by using a prototype 32-channel phased-array coil. With a SENSE acceleration factor of 4 = 2 × 2, the scan time of a full z-spectrum with 26 frequencies (water saturation as a function of transmitter frequency offset relative to water) was less than 10 min for the entire brain coverage.

Materials and Methods

Pulse Sequence Design

The 3D CEST sequence consists of three sections: RF saturation, lipid suppression and image acquisition using 3D GRASE (Fig. 1). The saturation section includes a series of four block RF pulses (200 ms duration each and 2 μT amplitude), each followed by a crusher gradient (10 ms duration and 10 mT/m strength). This interleaved approach was used to satisfy amplifier requirements regarding unblank time and duty cycle. Lipid suppression was achieved using chemical-shift selective removal with an asymmetric frequency-modulated (FM) lipid suppression pulse (flip angle 100° and 17.6 ms duration), followed by a crusher gradient (2 ms duration and 22 mT/m strength). Contrary to a frequency modulation based on a symmetric adiabatic full passage profile (AFP), this pulse was designed by combining two adiabatic half passage profiles, one with a sharp transition band and the other with a broad transition band (25). Note that in current implementation, this pulse was not used as an adiabatic inversion pulse but as an excitation pulse that rotates the lipid magnetization into the transverse plane for dephasing by the followed crusher gradient. The transition band of this FM excitation pulse was placed 300 Hz upfield from water (see the Results section), so the suppression width covered the entire lipid spectrum. The 3D GRASE section consisted of a slab-selective 90° excitation pulse (bandwidth = 1.6 kHz) and 22 slab-selective 180° refocusing pulses (bandwidth = 722 Hz), corresponding to a turbo spin-echo (TSE) factor of 22 in the right-left (RL) direction. Each repetitive period in the spin-echo train (echo spacing 18 ms) contained 7 echo-planar imaging (EPI) readout lines in the anterior-posterior (AP) direction, with EPI blip gradients in the superior-inferior (SI) direction. The phase-encoding ordering in the RL direction was set to acquire the center of k-space first to ensure the optimal signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and desired contrast with respect to saturation intensity. Within each TR of 2.5 s, the durations of the saturation, lipid suppression and imaging sections were 840 ms, 20 ms and 404 ms, respectively. The specific absorption rate (SAR) was 1.2 W/kg for TR = 2.5 s, within Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines.

FIG. 1.

Sequence diagram of 3D CEST imaging with GRASE readout. The sequence consisted of 4 block saturation pulses (200 ms each, 2 μT), a frequency modulated lipid suppression pulse, and 3D GRASE image acquisition with TSE in the y (phase) direction and EPI in the z (slice) direction. The dotted lines in the Gx direction are the Maxwell gradients. TSE factor = 22, EPI factor = 7, SENSE factor = 2 × 2, TR = 2.5 s.

Images were acquired in an oblique-axial plane, parallel to the line connecting the anterior and posterior commissures (AC-PC). The field of view (FOV) in the SI direction was 132 mm (30 points, resolution 4.4 mm). An oversampling factor of 1.8 was used to avoid fold-over artifacts. FOV was 212 mm in the AP direction and 186 mm in the RL direction, with 2.2 mm × 2.2 mm nominal resolution. With the defined resolution, FOV, and two-fold SENSE acceleration in the RL direction, 44 readout lines were needed for one plane in k-space. A single-shot sequence with 44 refocusing pulses after 800 ms of RF saturation would exceed the duty cycle limit of the RF amplifier when using body coil transmit. We therefore set the TSE factor to 22 and the EPI factor in the SI direction to 7 to balance the image quality and scan time. With SENSE acceleration factors of 2 × 2 in the RL and SI directions, the final imaging matrix was 96 (AP) × 44 (RL) × 28 (SI). In one TR, 154 (22 × 7) k-space lines were acquired and one 3D volume was acquired in 8 TRs (2 TSE shots in RL and 4 EPI shots in SI). The scan time for the whole volume at each saturation frequency offset was 2.5 s × 8 = 20 s, so the scan time for a whole brain z-spectrum with 26 frequencies was 8:40 min.

B0 Shimming and B1 Optimization

A rapid B0 and B1 mapping sequence was executed to simultaneously acquire B0 and B1 maps for the whole brain (26). A tilted “shimbox” (green box in Fig. 2a) was used to define the region of interest (ROI) of B0 shimming for the entire cerebrum. The region containing cerebellum (red polygon in Fig. 2b) was defined manually in lower slices (dashed red lines in Fig. 2a) of the B0 maps. Shimming parameters (up to 2nd order) were numerically optimized for the whole brain and scanner’s center frequency (F0) was subsequently determined by the fitted water spectrum (purple line in Fig. 2c). In addition, RF amplifier’s drive scale was determined using B1 values in the central region of the brain.

FIG. 2.

Geometric prescription of 3D CEST sequence in the brain. a: 3D imaging box (yellow) covering the entire brain, parallel to the AC-PC line. Shimbox (green) covering nearly the entire cerebral area. b: Cerebellum area manually included in lower slices of B0 maps for shimming. c: Scanner’s center frequency determined on water signals in shimmed regions only, excluding sinus region.

Data Acquisition

Experiments were performed on an 3T MRI scanner (‘Achieva’, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) using body coil transmit and a prototype 32-channel phased-array coil for reception (Invivo, Inc. Gainsville, Fl). In a phantom study, a box of homogenous eggwhite solution with 10% protein concentration was used, and the 3D GRASE sequence was compared with a multi-slice spin-echo (SE) sequence with the identical saturation scheme. The frequency sweep corresponded to a full z-spectrum with 26 frequency offsets: off (S0 image), 0, ±0.5, …, and ±6 ppm (at an interval of 0.5 ppm), and 12 points or slices were acquired. Both 3D and multi-slice acquisitions were repeated five times and averaged.

Five healthy subjects participated in this study with written informed consent according to Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines. The frequency offset of the FM lipid suppression pulse which provided best lipid suppression was determined experimentally using a spin-echo spectroscopic acquisition. In a series of spectroscopic scans, the frequency offset of the FM suppression pulse was moved from −600 to −200 Hz with respect to the water resonance in 50 Hz increments, and spectra were quantitatively compared by integrating the residual lipid signals. With the determined value of −300 Hz, the performance of the FM suppression pulse in the 3D GRASE sequence was evaluated by comparing images with and without the suppression pulse at four RF saturation frequency offsets: off (S0 image), 0, and ±3.5 ppm. After optimization, this offset (−300 Hz) was used for all CEST imaging applications. Similar to the phantom studies, the 3D imaging volume was sampled with 26 frequency offsets: off (S0 image), 0, ±0.5, …, and ±6 ppm (at an interval of 0.5 ppm).

Data Analysis

One of the main requirements in CEST imaging analysis is to remove contributions from competing water saturation effects, such as direct water saturation and conventional MT contrast (MTC) (27). This is generally implemented by using the asymmetry analysis of a magnetization transfer ratio (MTR = 1 − Ssat/S0) with respect to the water frequency:

| [1] |

where Ssat and S0 are the signal intensities with and without selective saturation, respectively. In vitro this approach removes the direct saturation effects successfully, but in vivo there is a remaining MTC asymmetry (28). Specifically for APT imaging, the MTR asymmetry at the amide proton frequency that is at 3.5 ppm downfield of the water resonance, MTRasym (3.5ppm), is not exclusively the amide proton transfer ratio (APTR) associated with mobile proteins and peptides in tissue, but contains the inherent asymmetry, (3.5ppm), associated with immobile macromolecules and membranes (9,10):

| [2] |

As discussed in previous papers (14,15), this analysis is also strongly influenced by B0 field homogeneity, because a small shift of the steep saturation curve will produce considerable asymmetry. This was removed by fitting and shifting the z-spectra as described below.

All data processing procedures were performed using the Interactive Data Language (IDL) (Research Systems, Inc., Boulder, CO, USA). Similar to previous papers (15,29), a full z-spectrum with 25 offsets between ±6 ppm was fitted using a 12th-order polynomial on a voxel-by-voxel basis. After this, the fitted curve was interpolated to a frequency resolution of 1 Hz (1537 points). The frequency with the lowest signal intensity was assigned to be the center of the water resonance, and the deviations of the water frequency in Hz were used to construct a map of water frequency offsets. To correct for the field inhomogeneity effects on a z-spectrum, the originally measured z-spectrum for each voxel was interpolated to 1537 points and shifted along the direction of the offset axis to correspond to 0 ppm at its lowest intensity. The realigned z-spectra were re-sampled back to 25 points for visual purposes, and the outermost points of ±6 ppm were excluded in the display.

The SNR values were measured using two extra Ssat images at 3.5 ppm that were acquired consecutively. For a selected ROI, the signal intensity was calculated from the average image. The noise level was estimated by the standard deviation of the intensities of the difference image in the same region.

Results

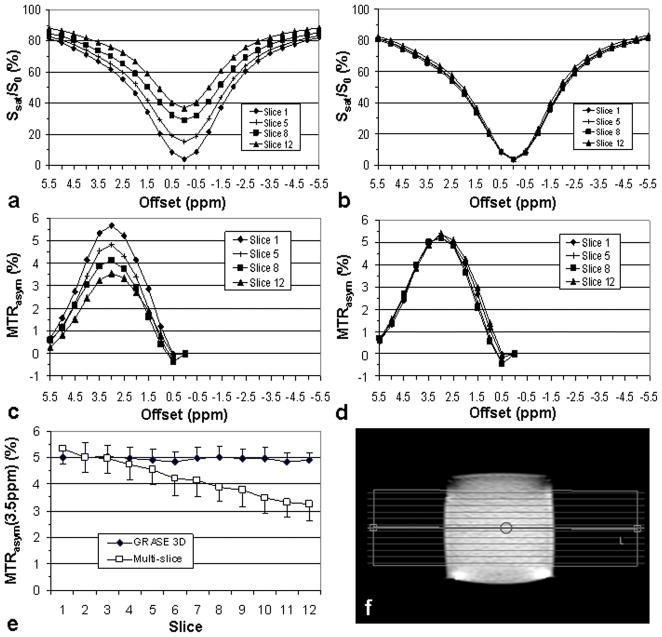

Figure 3 shows z-spectra and MTRasym spectra acquired for a homogeneous eggwhite phantom using multi-slice SE and 3D GRASE sequences. While signal intensities in both z-spectra and MTRasym spectra varied as a function of the slice order in the multi-slice SE sequence (Fig. 3a and c), the 3D GRASE sequence produced uniform spectral intensities across the slices (Fig. 3b and d). Signal losses in the multi-slice acquisition are due to T1 relaxation losses with respect to the order in which the slices were acquired, as described previously by other investigators (21,22). As a consequence, except for one slice, MTRasym(3.5ppm), containing the APT signal, was consistently higher for the 3D GRASE sequence than for the multi-slice SE sequence (Fig. 3e). For the latter, the average MTRasym(3.5ppm) values reduced from 5.3% ± 0.6% (1st slice) to 3.2% ± 0.6% (12th slice), corresponding to a 39% ± 1% contrast loss across slices, which would be even larger in vivo due to the shorter T1 of water.

FIG. 3.

Volumetric CEST imaging on a homogenous eggwhite phantom using multi-slice SE and 3D GRASE acquisition. a,b: z-spectra from 4 of 12 slices using multi-slice SE (a) and 3D GRASE (b). c,d: Corresponding MTRasym plots for a and b, respectively. e: MTRasym(3.5ppm) values measured by the two methods as a function of the acquired time order. 3D GRASE shows a more uniform CEST response across slices than multi-slice SE. f: Slice locations in eggwhite phantom.

Figure 4a shows the in vivo procedure used to determine the frequency offset of the FM lipid suppression pulse. The optimum was determined to be −300 Hz, at which frequency the majority of the lipid signals were suppressed (pink spectrum) while the expanded water resonance (shaded area) was affected minimally. Figure 4b and c shows several slices of 3D GRASE images acquired without and with lipid suppression, respectively. In Fig. 4b, lipid artifacts in the form of rings within the scalp were clearly visible in the Ssat(3.5ppm) and MTRasym(3.5ppm) images towards the top of the brain. These lipid artifacts were absent in the images with lipid suppression in Fig. 4c.

FIG. 4.

Determination of the frequency offset for the FM lipid suppression pulse and the effect of lipid suppression in the 3D GRASE sequence. a: MR spectra at five different frequency offsets and the integral of residual lipid signals as a function of the offset (dashed plot). The dashed plot reflects the sharp edge of the suppression pulse. At an offset of −300 Hz (pink spectrum), which was used in this study, the lipid resonance is sufficiently suppressed (pink dot in the dashed plot) while the water resonance is not affected significantly (shaded area). b,c: The saturated images at ±3.5 ppm and MTRasym(3.5ppm) images for three middle-top slices (in three columns) without and with lipid suppression. Without lipid suppression, ring-like hypointensities (white arrow) appear in the MTRasym(3.5ppm) images.

Figure 5 shows the S0 images, water center-frequency offset maps, and MTRasym(3.5ppm) images before and after B0-inhomogeneity correction for six slices from a typical subject. The B0 field inhomogeneity as seen in the fitted offset maps was typically less than 20 Hz in the relevant brain regions, but could be more than 100 Hz near air-tissue interfaces (sinus, ear). This B0 field inhomogeneity caused artifacts in the uncorrected MTRasym(3.5ppm) images, most of which were removed in the corrected MTRasym(3.5ppm) images through the realignment of the water center frequency.

FIG. 5.

Unsaturated (S0) images, calculated water center-frequency offset maps, uncorrected MTRasym maps at 3.5 ppm and corresponding corrected MTRasym maps for six typical slices. B0 inhomogeneity (solid black arrow) near air-tissue interfaces (sinus, ear) caused visible large artifacts (open arrow) in the MTRasym maps at 3.5 ppm. With lipid suppression and B0 correction, all MTRasym(3.5ppm) maps (bottom row) appear reasonably homogeneous.

Figure 6 shows a comparison of CEST image intensities in three brain regions from healthy subjects (n = 5). At three marked ROIs, namely, cerebellum, cerebral white matter (WM), and cerebral gray matter (GM), the SNR values measured were 46 ± 6, 35 ± 9, and 49 ± 9 for these locations, respectively. Figure 6b and c shows z-spectra and MTRasym spectra from those ROIs. The fact that MTRasym was lower at 3.5 ppm than at 2–3 ppm can be attributed to the presence of the negative conventional MTC asymmetry (28), as clearly seen at the offsets of >5 ppm. Average MTRasym(3.5ppm) over these healthy subjects was significantly higher in cerebellum (1.1% ± 0.4%) than in GM (0.2% ± 0.3%; two-tailed, paired t-test, p = 0.002) and WM (0.4% ± 0.4%; p = 0.02). There was negligible difference in MTRasym(3.5ppm) between the selected GM and WM areas (p > 0.2).

FIG. 6.

Comparison of the experimental results of 3D CEST imaging in different brain regions on healthy subjects (n = 5). a: The SNRs at three ROIs (cerebellum, cerebral WM and cerebral GM, each with about 40 voxels). b: z-spectra in these three ROIs. c: Corresponding MTRasym plots. MTRasym(3.5ppm) is significantly higher in cerebellum than in cerebrum (GM, p = 0.002; WM, p = 0.02).

Discussion

A whole-brain CEST imaging technique was developed for use on clinical scanners. As also demonstrated for several other imaging modalities (23,24), the 3D GRASE readout offers several advantages, some of which are particularly favorable for CEST. First, whole-brain CEST imaging is better realized with a 3D acquisition because each line of k-space contributes to all reconstructed images uniformly. Multi-slice acquisition, on the other hand, suffers from different inherent contrast from slice to slice caused by time-dependent saturation losses. The difference in MTRasym(3.5ppm) between cerebellum and cerebrum as seen by the 3D GRASE sequence in this study is in agreement with a previous measurement using the 3D fast low angle shot (FLASH) sequence (30). Obviously, this finding could not reliably be detected by the multi-slice SE sequence due to differences in contrast between slices. Second, the transverse magnetization for image acquisition in the 3D GRASE approach is generated by a single 90° excitation pulse. Since the signal is excited shortly after saturation (with only a short delay for lipid suppression), the water magnetization with the maximum transferred saturation is rotated into the transverse plane. Note that during the consecutive refocusing pulses, the recovered magnetization after saturation is not excited directly and therefore does not contribute to the acquired CEST contrast. Third, a 3D readout, especially when combined with large receiver coil arrays, reduces the scan time by allowing SENSE accelerations in two phase-encoding directions. Specifically, the 3D GRASE readout with separate TSE (RL) and EPI (SI) directions enables an efficient data acquisition scheme in which 154 k-space lines could be acquired in one TR.

Diamagnetic CEST imaging such as APT is particularly prone to lipid artifacts because chemical shift difference between water (4.75ppm) and lipid resonances (around 1.3 ppm) is close to that between water and the amide protons at 8.3 ppm, but of opposite sign. When acquiring the APT reference image with a frequency offset at −3.5 ppm, Ssat(−3.5ppm), lipid signals are saturated. However, when acquiring the Ssat(3.5ppm) image, the lipid signals are not suppressed, thus leading to lipid artifacts in the MTRasym(3.5ppm) images. Additionally, fast imaging in the brain using EPI methods has been known to produce ghosting artifacts from lipid signals in the scalp (20). Particularly, when using a 32-channel phased-array coil for reception and lipid regions being closest to the coil elements, lipid signals are picked up with very high SNR. In order to obtain an appropriate APT image, the lipid signals should be suppressed equally at both offsets before image acquisition. In our 3D GRASE sequence, the asymmetric FM suppression pulse permits the sharper transition band to be placed closer to the water resonance than a standard symmetric suppression pulse. The approach of using asymmetric suppression pulses to improve suppression performance and better control the spectral locations of the cutoff edges was demonstrated recently in spectroscopy as a dual-band suppression sequence (31). Our experimental results (Fig. 4) show that in the offset range of −250 to −350 Hz (−300 Hz was used in this study), the lipid resonance is sufficiently suppressed while the water resonance is not affected significantly. Thus, the FM lipid suppression pulse would work very well in most of brain areas. In the presence of large B0 inhomogeneities (beyond ±100 Hz, which may be seen in sinus and ear areas), the lipid suppression may become worse and the water signal may be affected. However, it is important to notice that MTRasym (namely, the CEST imaging intensity; see Eq. [1]) would remain unaffected, because all acquired images have the same percent signal reduction.

The current in vivo results demonstrate that the 3D GRASE sequence can successfully acquire Ssat images with high SNR values and reliable, artifact-free MTRasym data across the whole brain. The quality of the results depends on various factors including the main magnetic field homogeneity and the accuracy of the 22 consecutive refocusing pulses of the GRASE readout over the volume of the brain. These factors were optimized by B0 shimming and B1 optimization using simultaneously acquired B0 and B1 maps. The ROI for B0 shimming was prescribed automatically for the cerebrum and manually defined polygons for the cerebellum, excluding the unwanted sinus region. Numerically optimized shim fields of up to 2nd order limited B0 inhomogeneity broadening to the range of 100–200 Hz (Fig. 2c) for the whole brain. The field map-based center frequency determination (Fig. 2c) placed the RF pulses specifically on the water signals in the defined ROI. The specificity and quality of B0 shimming results can be seen in the lowest slice in Fig. 6a where the cerebellum is clearly visualized with high SNR, while the extra-axial regions in the rest of the slice were blurred. The accuracy of the transmit B1 level is important for the image homogeneity over the whole brain. In addition, a small deviation of B1 value can also be accumulated by the consecutive refocusing pulses to cause significant artifacts. In the future improved transmit B1 homogeneity will likely be possible using multiple transmitter systems.

Finally, the fact that MTRasym for the brain was lower at 3.5 ppm than at 2–3 ppm can be attributed to the presence of the negative conventional MTC asymmetry, as clearly seen at the offsets of >5 ppm (Fig. 6c). If the solid-like macromolecular MTC effects were symmetric with respect to the water resonance, according to Eq. [1], the additional CEST downfield from the water signal would give rise to a positive MT difference, as observed in phantoms (5). However, it is interesting that the resulting asymmetry curves (Fig. 6c) show a varying MT difference that is initially slightly positive and then becomes negative, which leads to the small MTRasym values at the offset of 3.5 ppm, and the shift of the maximum from 3.5 ppm to 2.5 ppm. This is due to the MTC effect that also has a slight asymmetry, with the MT center frequency in the aliphatic range. Further, it has been shown previously (28) that the conventional MTC asymmetry is power dependent. This complicates CEST imaging quantification in vivo. However, as far as the APT images (namely, MTRasym(3.5ppm) images) are concerned, with the RF saturation power similar to that used in this study (2 μT), one can expect almost zero MTRasym(3.5ppm) for normal brain tissue, positive MTRasym(3.5ppm) for brain tumors [10,14–16,29], and negative MTRasym(3.5ppm) for ischemic brain [9,11]. Consequently, these pathologically different lesions can easily be visualized for practical applications.

Conclusions

A 3D GRASE readout was used to acquire whole-brain CEST images in less than 10 min. The sequence parameters were determined to satisfy scanner’s hardware constraints and to efficiently combine TSE, EPI and 2D SENSE for scan time reduction. Artifacts due to B0 and B1 field inhomogeneity and lipid signals could be successfully addressed. These data demonstrate the feasibility of time-efficient whole-brain CEST imaging at 3T, indicating feasibility for clinical integration.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Ronald Ouwerkerk, Dr. Michael Schär and Mr. Joe Gillen for experimental assistance. Dr. Peter van Zijl and Dr. Peter Barker are paid lecturers for Philips Medical Systems. This arrangement has been approved by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. This work was supported in part by grants from NIH (EB009112, EB009731 and RR015241), Brain tumor funders’ collaborative and Dana Foundation.

References

- 1.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) J Magn Reson. 2000;143:79–87. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging and spectroscopy. Progr NMR Spectr. 2006;48:109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aime S, Crich SG, Gianolio E, Giovenzana GB, Tei L, Terreno E. High sensitivity lanthanide(III) based probes for MR-medical imaging. Coord Chem Rev. 2006;250:1562–1579. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Leon-Rodriguez LM, Lubag AJM, Malloy CR, Martinez GV, Gillies RJ, Sherry AD. Responsive MRI agents for sensing metabolism in vivo. Acc Chem. 2009;42:948–957. doi: 10.1021/ar800237f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goffeney N, Bulte JWM, Duyn J, Bryant LH, van Zijl PCM. Sensitive NMR detection of cationic-polymer-based gene delivery systems using saturation transfer via proton exchange. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8628–8629. doi: 10.1021/ja0158455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang S, Winter P, Wu K, Sherry AD. A novel europium(III)-based MRI contrast agent. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123(7):1517–1578. doi: 10.1021/ja005820q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aime S, Delli Castelli D, Terreno E. Highly sensitive MRI chemical exchange saturation transfer agents using liposomes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:5513–5515. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langereis S, Keupp J, van Velthoven JLJ, de Roos IHC, Burdinski D, Pikkemaat JA, Grull H. A temperature-sensitive liposomal 1H CEST and 19F contrast agent for MR image-guided drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1380–1381. doi: 10.1021/ja8087532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou J, Payen J, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ, van Zijl PCM. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nature Med. 2003;9:1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou J, Lal B, Wilson DA, Laterra J, van Zijl PCM. Amide proton transfer (APT) contrast for imaging of brain tumors. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:1120–1126. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jokivarsi KT, Grohn HI, Grohn OH, Kauppinen RA. Proton transfer ratio, lactate, and intracellular pH in acute cerebral ischemia. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:647–653. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vinogradov E, He H, Lubag A, Balschi JA, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE. MRI detection of paramagnetic chemical exchange effects in mice kidneys in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:650–655. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dagher AP, Aletras A, Choyke P, Balaban RS. Imaging of urea using chemical exchange-dependent saturation transfer at 1.5T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12:745–748. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200011)12:5<745::aid-jmri12>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones CK, Schlosser MJ, van Zijl PC, Pomper MG, Golay X, Zhou J. Amide proton transfer imaging of human brain tumors at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:585–592. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou J, Blakeley JO, Hua J, Kim M, Laterra J, Pomper MG, van Zijl PCM. Practical data acquisition method for human brain tumor amide proton transfer (APT) imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:842–849. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wen Z, Hu S, Huang F, Wang X, Guo L, Quan X, Wang S, Zhou J. MR imaging of high-grade brain tumors using endogenous protein and peptide-based contrast. NeuroImage. 2010;51:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mougin OE, Coxon RC, Pitiot A, Gowland PA. Magnetization transfer phenomenon in the human brain at 7T. NeuroImage. 2010;49:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, van Zijl PCM. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:1441–1450. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration in vivo by chemical exchange-dependent saturation transfer (gagCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2008;105:2266–2270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun P, Zhou J, Sun W, Huang J, van Zijl PC. Suppression of lipid artifacts in amide proton transfer (APT) imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:222–225. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun PZ, Murata Y, Lu J, Wang X, Lo EH, Sorensen AG. Relaxation-compensated fast multislice amide proton transfer (APT) imaging of acute ischemic stroke. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:1175–1182. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixen WT, Hancu I, Ratnakar SJ, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE, Alsop DC. A multislice gradient echo pulse sequence for CEST imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2009;63:253–256. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunther M, Oshio K, Feinberg DA. Single-shot 3D imaging techniques improve arterial spin labeling perfusion measurements. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:491–498. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poser BA, Norris DG. 3D single-shot VASO using a maxwell gradient compensated GRASE sequence. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:255–262. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang T-L, van Zijl PCM, Garwood M. Asymmetric adiabatic pulses for NH selection. J Magn Reson. 1999;138:173–177. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schar M, Vonken EJ, Stuber M. Simultaneous B0- and B1+-map acquisition for fast localized shim, frequency and RF power determination in the heart at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2009;63:419–426. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henkelman RM, Stanisz GJ, Graham SJ. Magnetization transfer in MRI: a review. NMR Biomed. 2001;14:57–64. doi: 10.1002/nbm.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hua J, Jones CK, Blakeley J, Smith SA, van Zijl PCM, Zhou J. Quantitative description of the asymmetry in magnetization transfer effects around the water resonance in the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:786–793. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salhotra A, Lal B, Laterra J, Sun PZ, van Zijl PCM, Zhou J. Amide proton transfer imaging of 9L gliosarcoma and human glioblastoma xenografts. NMR Biomed. 2008;21:489–497. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu H, Gillen JS, Barker PB, van Zijl PC, Zhou J. 3D amide proton transfer (APT) imaging of the whole brain at 3T. Honolulu; Hawaii: 2009. p. 4475. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu H, Ouwerkerk R, Barker PB. Dual-band water and lipid suppression for MR spectroscopic imaging at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22324. (Published Online: 30 Apr 2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]