Abstract

The ability to measure oxygen partial pressure (pO2) with high temporal and spatial resolution in three dimensions is crucial for understanding oxygen delivery and consumption in normal and diseased brain. Among existing pO2 measurement methods, phosphorescence quenching is optimally suited for the task. However, previous attempts to couple phosphorescence with two-photon laser scanning microscopy have faced substantial difficulties because of extremely low two-photon absorption cross-sections of conventional phosphorescent probes. Here, we report the first practical in vivo two-photon high-resolution pO2 measurements in small rodents’ cortical microvasculature and tissue, made possible by combining an optimized imaging system with a two-photon-enhanced phosphorescent nanoprobe. The method features a measurement depth of up to 250 µm, sub-second temporal resolution and requires low probe concentration. Most importantly, the properties of the probe allowed for the first direct high-resolution measurement of cortical extravascular (tissue) pO2, opening numerous possibilities for functional metabolic brain studies.

INTRODUCTION

The functioning of the brain is critically dependent on oxygen supply.1–3 Previous measurements indicate great variability in both vascular and tissue pO24–7 that is likely to arise from variations in blood flow and metabolic demand in different regions of the brain. However, the precise mechanisms of the regulation of the oxygen supply are still largely unknown,8 in part because of an inability to accurately and rapidly measure cortical vascular and tissue pO2 at increased depth with high resolution. The existing oxygen measurement methods (e.g., electrodes,7 binding of nitroimidazole-based drugs,9 electron paramagnetic resonance methods,10, 11 hemoglobin optical absorption-based methods12–14) suffer from either low sensitivity or low spatial or temporal resolution, or are invasive by nature. Among optical approaches, oxygen-dependent quenching of phosphorescence15 stands out in its ability to provide fast absolute measurements of pO2, which are unaffected by changes in optical properties of the tissue. Previous studies have applied phosphorescence quenching to image oxygen in a variety of biological tissues,16–20 including examples of microscopy.21

The combination of phosphorescence quenching with two-photon microscopy22 is a natural synergy since two-photon excitation, which is characterized by a high degree of spatial confinement and a reduced risk of photodamage, should allow pO2 measurements deeper in the brain with high resolution. Unfortunately, direct coupling of phosphorescence with two-photon microscopy is hampered by extremely low two-photon absorption cross-sections of phosphorescent probes, necessitating very high excitation powers, long acquisition periods and/or exceedingly high probe concentrations.23, 24 Here we show that, by using a specially designed two-photon-enhanced phosphorescent nanoprobe PtP-C34325 and an optimized microscopy setup, this limitation can be overcome, allowing for pO2 measurements in capillaries down to 240 µm below the brain surface with high (~0.5 s per point) temporal resolution. Importantly, the signal in these measurements is phosphorescence lifetime, not intensity, and thus it is independent of the local probe concentration. We report an extensive map of intravascular pO2 values as they vary from the pial arteries through the capillary network into the draining veins. Furthermore, the unique properties of the probe allowed for the first direct high-resolution measurements of cortical tissue pO2 in vivo down to 100 µm below the brain surface. We demonstrated the functionality of this method by measuring spatio-temporal variations in tissue pO2 arising from hypoxia and by simultaneously measuring intravascular and tissue (extravascular) pO2.

RESULTS

Two-photon-enhanced phosphorescent probe PtP-C343

PtP-C34325 (Supplementary Fig. 3), belongs to the family of dendritically protected phosphorescent probes.26 Its core is formed by a highly phosphorescent Pt porphyrin (PtP), encapsulated inside poly(arylglycine) dendrimer. The dendrimer protects the porphyrin from interaction with components of the measurement system and controls the rate of oxygen quenching. Several coumarin-343 (C343) units, attached at the periphery of the dendrimer, capture two-photon excitation energy and transfer it non-radiatively to the porphyrin. Upon excitation, PtP undergoes fast intersystem crossing into its triplet state and emits phosphorescence, which is quenched by molecular oxygen in a diffusion-controlled manner. The lifetime of the phosphorescence decay (typically several tens of microseconds) is inversely proportional to the pO2 (via Stern-Volmer relationship), thus forming the signal for analytical pO2 determination.

The remaining termini on the dendrimer in PtP-C343 are modified with polyethyleneglycol (PEG) residues. PEGylation ensures that the probe's signal is insensitive to proteins and other macromolecular solutes in biological systems. Dendritic porphyrin-based dyes used earlier could operate only when bound to albumin in the blood. However, at higher concentrations (above ~10−5 M), a significant fraction of these probes remain unbound, causing phosphorescence decays to become poorly interpretable and pO2 measurements irreproducible and inaccurate. PEGylated probes do not require binding to albumin for measurements in the physiological oxygen range and, if required, can be used at very high concentrations without causing ambiguity in pO2 determination. The probe used in this study was modified with polyethyleneglycol residues of average Molecular Weight (Av. MW) 2,000, as opposed to shorter polyethyleneglycols (Av. MW 750), used in the original molecule.25 This rendered the probe less aggregated and increased its signal dynamic range.

Experimental setup

For two-photon in vivo brain imaging we constructed a microscope with high signal collection efficiency and photon-counting detection (Fig. 1). We performed imaging on the brain of anesthetized animals through sealed cranial windows, either injecting the phosphorescence probe into the vasculature through the femoral artery or pressure-injecting it directly into the brain tissue. We obtained structural images of the cortical vasculature by imaging intravenously administered fluorescein-dextran. We excited phosphorescence by trains of femtosecond pulses from a Ti:Sapphire oscillator, gated by an electro-optic modulator, and acquired decays by averaging multiple excitation cycles. Each cycle consisted of a 20–80 µs excitation gate, followed by 300-µs collection period, using an average laser power during the excitation gate of ~10 mW at the laser focus. We estimate that under this excitation regime the emitting volume had ~2 µm lateral (XY) and ~5 µm axial (Z) dimensions. This increase in the excitation volume, compared to its true diffraction-limited size, was caused by saturation effects.25 Nevertheless, these dimensions still permitted sufficient spatial resolution, while allowing for a much stronger signal and therefore a faster temporal response.

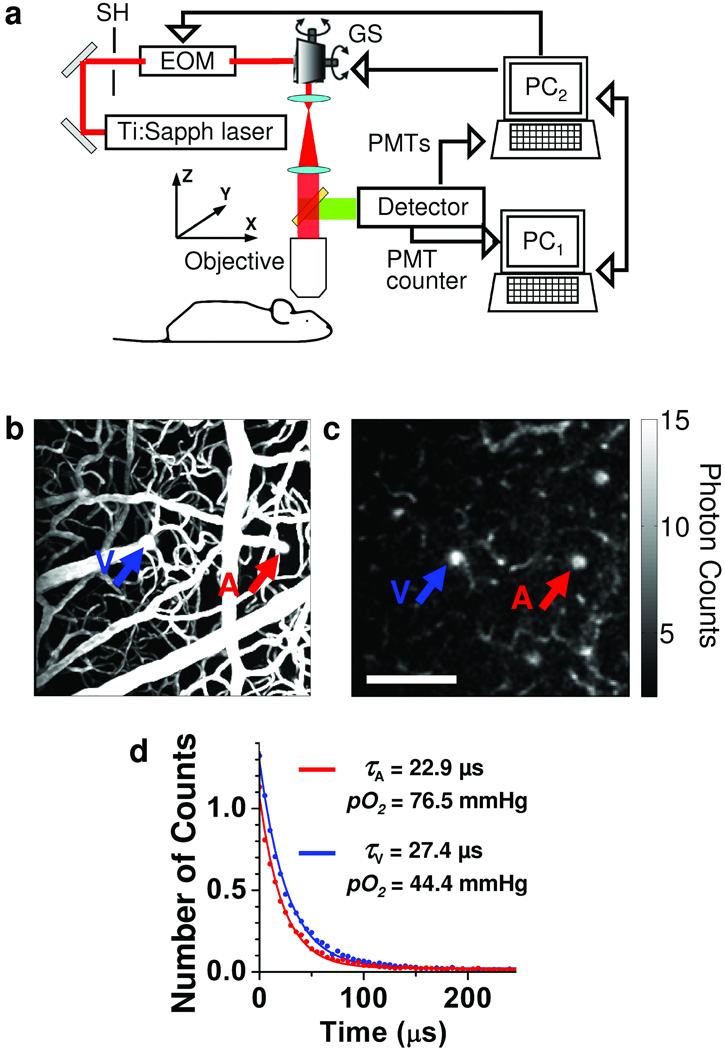

Figure 1. Phosphorescence detection procedure.

(a) Experimental setup. PC1 and PC2 – computers, SH – shutter, EOM – electro-optic modulator, GS – galvanometer scanner. (b) Maximum intensity projection (MIP) along z direction of a 250 µm thick stack in the mouse cortex. The vasculature was labeled with FITC. (c) Phosphorescence intensity image of microvasculature obtained at 166 µm depth below the cortical surface. The color bar shows the average number of counts in each pixel collected during single phosphorescence decay. Scale bar, 100 µm. (d) Experimental measurement (dots) and corresponding single exponential fits (solid lines) of two phosphorescence decays from the diving arteriole (A, red) and ascending venule (V, blue), with positions marked with the arrows in (b) and (c).

In a typical experiment, we performed detection in two steps. First, we raster-scanned the excitation beam over the field of view, rendering two-dimensional survey maps of the integrated emission intensity (250 × 250 pixels, acquired in ~25 s). An example of such a single-plane scan performed 166 µm below the brain surface (Fig. 1c), demonstrates the ability of the system to resolve the structure of the microvasculature down to the capillary level. After mapping the tissue, we averaged 500–2,000 phosphorescence decays in selected locations within the vasculature for accurate pO2 determination (Fig. 1d). This acquisition time corresponded to a temporal resolution of 0.16–0.76 s per single-point pO2 measurement, while the measurement of the entire vasculature stack required up to 30 min. Finally, using Stern-Volmer calibration plots, we converted phosphorescence lifetimes, obtained by fitting, into pO2 values.

Oxygen tension in cortical microvasculature

In a typical experiment we measured approximately 100 pO2 values in 30-µm steps down to 240 µm below the cortical surface in the mouse brain (Fig. 2a). The obtained pO2 values agreed well with previously published measurements in small rodent cortices.5, 7 We were able to directly measure pO2 in capillaries (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 1) and in consecutive vascular branches. Starting from the pial arteriole (Fig. 2b), pO2 values decrease to 61.1 mmHg, 61.8 mmHg, 48.2 mmHg, 42.8 mmHg, and 29.7 mmHg along the descending vessels down to the capillary level, at a depth of 240 µm.

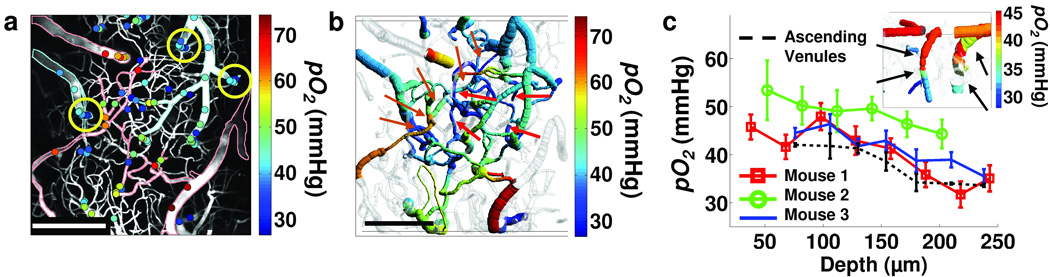

Figure 2. Measurement of pO2 in cortical microvasculature.

(a) Measured pO2 values in microvasculature at various depths, overlaid on the MIP image of the vasculature structure (grey). Digital processing was performed to remove images of the dura vessels. For easier identification, the edges of the major pial arterioles and venules were outlined in red and blue, respectively. Scale bar, 200 µm. (b) Composite image showing a projection of the imaged vasculature stack. Four pO2 measurement locations in the capillary vessels at 240 µm depth are marked with red arrows. Five orange arrows point to the consecutive branches of the vascular tree, from pial arteriole (arrow at left) to the capillary level and further to the connection with ascending venule (arrow at upper right). Scale bar, 200 µm. (c) The pO2 dependence with cortical depth in three mice averaged across all vessels excluding pial arterioles. Dotted black line shows average pO2 dependence with cortical depth in three ascending venules, at positions outlined with the circles in (a). The error bars represent standard error at each depth. Composite image in the corner shows a side projection of the two circled ascending venules from the upper right corner in (a). These ascending venules are marked with black arrows in (c).

We generally observed a decrease in the vascular pO2 with an increase in the cortical depth (Fig. 2c). The average pO2 (measured in three animals; excluding pial arterioles) decreased by ~10 mmHg moving from the pial veins down to a depth of ~240 µm. This observation supported previous findings6, 27 showing a relatively rapid initial decrease of tissue pO2 with cortical depth. Interestingly, we also observed an average pO2 increase of ~7 mmHg towards the cortical surface in the three ascending venules (Fig. 2c), which drain blood from the deeper cortical layers, suggesting the possibility of oxygen efflux from the tissue into the venous compartment. A recent report makes a similar observation using the measurement of hemoglobin saturation as a vascular pO2 indicator.28

Oxygen tension in cortical tissue and microvasculature

To perform tissue pO2 measurement, we injected PtP-C343 directly into the interstitial space. Based on the phosphorescence intensity measurements, the concentration of PtP-C343 in the tissue in these experiments was comparable to or lower than that used in vascular measurements. Importantly, two-photon excitation made it possible to confine the phosphorescence quenching by oxygen to the immediate vicinity of the focal plane, thus minimizing oxygen consumption and/or phototoxicity. Other studies show that oxygen consumption can skew tissue pO2 measurements at high excitation intensities.21 In our experiments, we could not observe any changes in the phosphorescence lifetime when performing multiple repetitive measurements at the same location.

We measured tissue pO2 values (Fig. 3) during normoxia in a rat in 29 locations ~100 µm below the cortical surface (Fig. 3c). The obtained values (6–25 mm Hg) were within the range of the previously established cortical tissue pO2 levels.5–7 We observed relatively high pO2 values (> 20 mmHg) close to a large pial artery (points 6–9), and a relatively steep pO2 decay at locations farther away from the artery (points 10–13). These results are in agreement with the existence of tissue pO2 gradients at the cortical surface.5–7

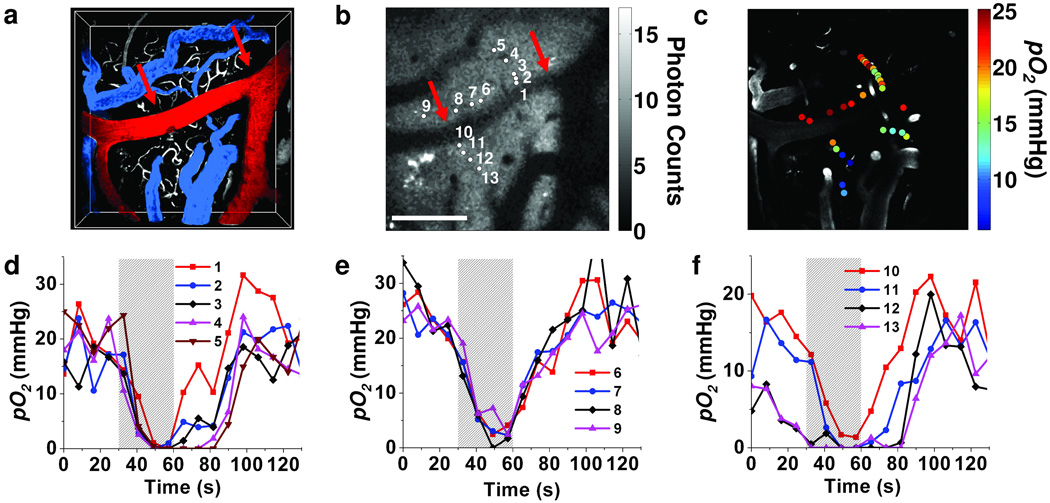

Figure 3. Measurement of pO2 in cortical tissue.

(a) Volumetric image of the 200 µm-thick FITC-labeled microvasculature stack in the rat cortex. A large pial artery (red, marked with arrows in (a) and (b)) and two pial veins (blue) are color-coded for easier identification. (b) An integrated phosphorescence intensity image at 100 µm depth. Grey bar represents average number of counts from single phosphorescence decay at each pixel. Scale bar, 200 µm. (c) Measured pO2 values during normoxia are overlaid with the grey-scale microvasculature structural image at 100 µm depth. (d)–(f) Temporal profiles of the measured pO2 values at selected locations (b) during hypoxia. The period of the hypoxia is indicated by the grey bar.

Two-photon phosphorescence lifetime measurements have the unique capability of simultaneous monitoring of tissue pO2 at multiple locations at variable depths, making it possible to conduct functional studies of the brain during transient changes in oxygenation. We acquired temporal pO2 profiles at selected locations (Fig. 3b) during hypoxia, created by 30-s respiratory arrest (Fig. 3d–f). We averaged 500 decays in each location every 8.2 s, requiring 0.19 s per measurement and we cycled the scan sequence for the duration of the experiment through all selected locations. We grouped the locations according to their distances from the artery. During hypoxia, oxygen rapidly depleted in all of the measured locations; however, we observed a clear correlation between the locations and the character of the temporal profiles. Thus, closer to the artery (Fig. 3e) pO2 decreased more slowly and recovered more quickly upon return to normal breathing; whereas in most locations farther away from the artery (Fig. 3d,f), pO2 decreased faster and recovered more slowly.

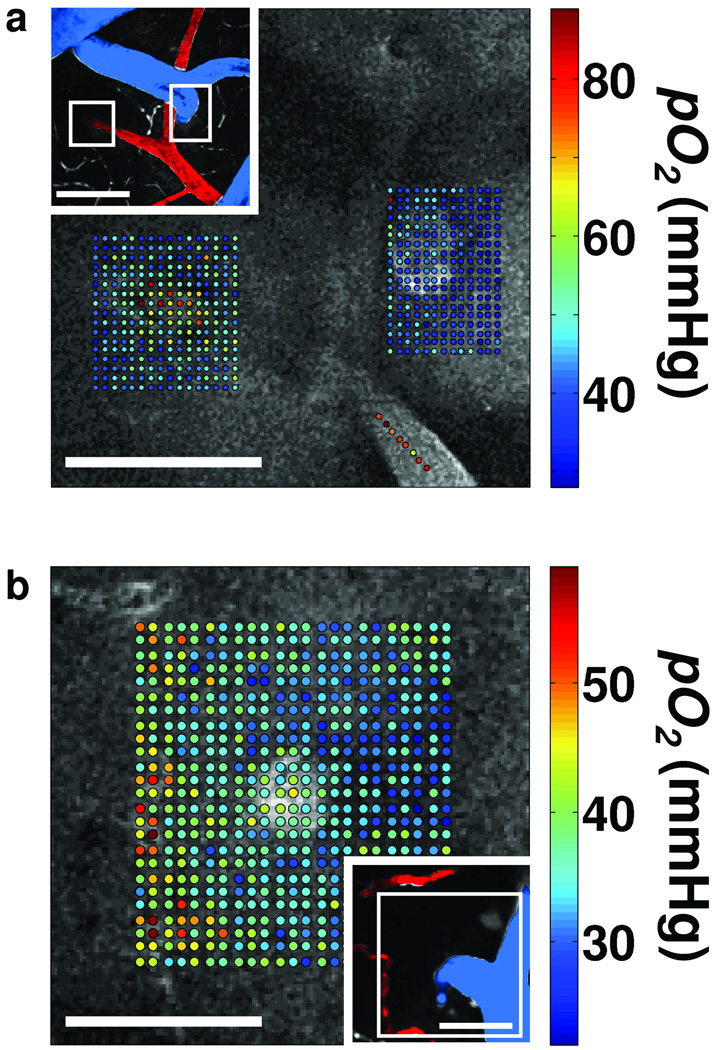

We introduced the probe into both the vasculature and the interstitial space in order to perform concurrent pO2 measurement in these two compartments. We obtained maps of pO2 values measured at several locations around and inside diving venules and ascending arterioles in the rat cortex (Fig. 4). A map of more than 500 locations (Fig. 4a) shows high pO2 values inside and elevated pO2 values around the diving arteriole. In contrast, we observed only slightly elevated intravascular pO2 in the ascending venule with respect to the surrounding tissue pO2. In a grid of pO2 measurements (Fig. 4b), covering the area of an ascending venule and branches of a small descending arteriole, slightly higher pO2 values are evident in the venule with respect to the surrounding tissue pO2. In addition, we noted an elevated tissue pO2 in the vicinity of the arterial branches.

Figure 4. Simultaneous measurement of pO2 in cortical vasculature and tissue.

(a) Measured pO2 values overlaid with the grey scale phosphorescence intensity image at 40 µm depth. Measurements were performed at locations of descending arteriole (left) and ascending venule (right). Measurement locations were also marked with the white rectangles in the inset (top left), which shows a MIP of 80 µm-thick FITC-labeled microvasculature stack. Artery (red) and vein (blue) are color-coded for easier identification. Scale bars, 100 µm. (b) Measured pO2 values overlaid with the grey scale phosphorescence intensity image at 60 µm depth. Measurements were performed at the location of an ascending venule. Measurement location is marked with the white rectangle in the inset (bottom right), showing MIP of 80 µm-thick FITC-labeled microvasculature stack. Ascending venule (blue) and branches of the descending arteriole (red) are color-coded for easier identification. Scale bars, 50 µm.

DISCUSSION

Oxygen is a key metabolite, and tissue oxygenation is one of the most critical parameters with respect to brain physiology and pathology. Nevertheless, imaging technologies for mapping brain oxygenation, especially at the microscopic level, are only beginning to be developed. The developed technique opens up numerous possibilities for metabolic studies in neuroscience that will advance our understanding of brain metabolism and function under normal and pathological conditions.

With respect to brain studies, the key advantages of the two-photon phosphorescence quenching technique are its minimal invasiveness and the possibility of achieving high temporal and spatial resolution at substantial cortical depths. The probe's signal is independent of pH throughout the physiological range and is not affected by the presence of biological macromolecules.25 Due to its relatively large molecular size (~3–4 nm in the folded state), PtP-C343 is characterized by a long half life (~2 h) in the circulation (Supplementary Fig. 2). We did not detect any leakage of the probe from the vasculature into the interstitial space in the brain. A convenient feature of the method is its absolute calibration, i.e. the probe constants need to be measured only once and do not require repetitive calibrations. Moreover, because the quenching reaction is independent of the pathway by which the probe is converted to its triplet state, calibration plots (phosphorescence lifetime τ dependence on pO2) are expected to be identical for single- and two-photon excitation. Indeed, calibration of PtP-C343 confirmed that with a properly selected excitation regime, Stern-Volmer plots obtained in vivo in the blood using the two-photon microscopy setup were the same as measured in a regular titration experiment using linear excitation (see Methods, and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3, for details).

It is important to keep in mind that in all quenching-based oximetry methods most of the photodamage occurs due to the products of the quenching reaction (singlet oxygen and other reactive oxygen species). Thus, it is necessary to optimize probe concentration/excitation regime in order to minimize undesirable phototoxic effects. Two-photon excitation makes it possible to avoid formation of toxic species everywhere along the excitation path, and to confine it to the immediate vicinity of the laser focus. As a result, singlet oxygen generation in our experiments was minimized. We performed tests of cell viability using apoptosis and neuronal degeneration sensitive stainings 24 h after measuring tissue pO2 in a dense grid pattern (Supplementary Fig. 4). In all cases, there was no evidence of phototoxicity.

Until now, the lack of technologies for direct 3D mapping of oxygen availability in the brain has been a major limiting factor in investigations of oxygen metabolism. Simultaneous imaging of intravascular pO2 and tissue pO2 gradients will allow direct measurement of oxygen extraction fraction and, when combined with measures of blood flow,29 the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen, the central parameters for interpretation of blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).1 Furthermore, this methodology can be directly applied in other areas, such as stroke, cancer, neurological conditions, and heart failure, where accurate non-invasive determination of pO2 is the key to understanding physiological function. The synergism of two-photon phosphorescent measurements with other two-photon microscopy tools for imaging of neuronal, vascular and metabolic activity opens the door to a more integrative approach for addressing critical questions regarding the order of pathological events in the progression of disease and promises to provide an objective way for screening of potential therapies.

METHODS

Imaging setup

We used a custom-built microscope setup in this study (Fig. 1a). The system was controlled by custom-designed software written in LabView (National Instruments). The optical beam was scanned in the XY plane by galvanometer scanners (6215H, Cambridge Technology, Inc.) and focused on the sample by an objective (Olympus 20X XLumPlanFL; NA=0.95). A motorized stage controlled the focal position along the vertical axis (Z), and an electro-optic modulator (ConOptics, Inc., extinction ratio ~500) served to gate the output of a Ti:Sapphire oscillator (840 nm, 80 MHz, 110 fs, Mai-Tai, Spectra-Physics). The maximal laser power on the object during excitation gate was ~90 mW when imaging at large cortical depths and 10–20 mW at the surface. Increases in the power were necessary when working at higher depth to compensate for scattering and to maintain approximately 10 mW power in the focal plane. The pulse duration was ~350 fs (assuming sech2 pulse shape), as measured at the sample. The emission was reflected by a dichroic mirror (LP 735 nm, Semrock) and detected by a detector array, consisting of four independent photomultiplier tubes (PMTs), with a large collection efficiency (~15 mm2 sr). The phosphorescence output was passed through a 680 ± 30 nm band-pass filter and forwarded to a photon-counting PMT module (H10770PA-50, Hamamatsu), whose output was acquired by a 50 MHz digital board (NI PCle-6537, National Instruments) and saved for later processing. In order to determine the phosphorescnece lifetime, we fitted the phosphorescence intensity decay with a single-exponential function using the non-linear least-squares method. The lifetime was converted to pO2 using the calibration plot obtained in independent oxygen titration experiments25 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Animal preparation

For imaging of pO2 in the microvasculature, we anesthetized CD-1 mice (male, 25–30 g, 10–12 weeks old) by isoflurane (1–2% in a mixture of O2 and N2O) under constant temperature. We then opened a cranial window in the parietal bone with intact dura and sealed it with a 150-µm-thick microscope coverslip. During the experiments, we used a catheter in the femoral artery to monitor the blood pressure (75–85 mmHg) and blood gases (pCO2: 36–39 mmHg, and pO2: 110–160 mmHg) and to administer the dyes. The concentration of PtP-C343 in the blood immediately after administration was ~16 µM. During the measurement period mice breathed a mixture of O2 and air under the same isoflurane anesthesia.

For measurements of pO2 in tissue (interstitial space), Sprague Dawley rats (250–320 g) were temperature controlled, anesthetized with isofluorane (1.5–2% in a mixture of O2 and air) and tracheotomized, and catheters inserted in the femoral artery and vein for administering the anesthesia and dyes and for measuring blood gases and blood pressure. We created a sealed cranial window in the center of the parietal bone with the dura removed. Before sealing the window, we pressure-injected ~0.1 µL of PtP-C343 (1.4×10−4 M) with the micropipette ~300 µm below the surface of the brain. We performed imaging a few hundred microns from the injection site. The probe spreading in the brain tissue appears to have been sufficiently slow to allow imaging of pO2 for several hours following the injection. During the measurements, we ventilated rats with a mixture of air and O2. Isofluorane was discontinued and anesthesia maintained with a 50 mg/kg intravenous bolus of alpha-chloralose followed by continuous intravenous infusion at 40 mg/(kg h). In the resting condition the systemic arterial blood pressure was 95–110 mmHg, pCO2 was 35–44 mmHg, and pO2 was 95–110 mmHg. We created hypoxic conditions by stopping the respirator for 30 s. We administrated intravenous bolus of Pancuronium Bromide (2 mg/kg) followed by continuous intravenous infusion at 2 mg/(kg h) during the breath-hold experiment to minimize possible animal motion. In all measurements, we compared the phosphorescence survey scans taken immediately before and after pO2 point measurements and inspected collected phosphorescence decays for signs of sudden intensity or decay slope change during acquisition, which could indicate motion artifact during the measurement. For simultaneous intravascular and tissue pO2 measurements, we used Sprague Dawley rats (90–120 g, 7 animals), applying the same surgical procedure. We adjusted intravascular concentration of the probe (10–30 µM) in each animal to obtain satisfactory visibility in phosphorescence survey images. While animal preparations with tracheotomized rats allow generally longer and better controlled experiments, the choice of mice and small rats was motivated by a need to limit the amount of probe used in the experiments involving intravascular pO2 measurements. All experimental procedures were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Sub-committee on Research Animal Care.

Construction of the composite images

We obtained structural images of the cortical vasculature following the pO2 measurements by labeling the blood plasma with Dextran-conjugated fluorescein (FITC, FD2000S, Sigma) and performing two-photon fluorescence imaging. We subsequently created a graph of the vascular network using a previously established procedure.30 We performed image processing and data analysis using custom-designed software in Matlab (MathWorks), code is available from the authors upon request. The locations in which oxygen tension were measured were co-registered with this image, and three-dimensional composite images were created with both vasculature structure (shades of gray) and color-coded measured pO2 values. We color-coded the latter by assigning a pO2 value either to the whole vessel segment between two branching points, or to the neighboring portion of the vessel segment if more than one pO2 measurement was performed in that segment. In addition, in some cases (Fig. 2b), for segments that did not have a measurement but joined at both ends with segments that had measurements within 100 µm, we assigned the average pO2 value of the connecting segments. Although not quantitative, this procedure allowed more complete visualization of the vascular tree. In the future, simultaneous measurement of pO2 and blood flow in the microvasculature29 will greatly improve the accuracy of pO2 estimation in the remaining parts of the vascular tree.

PtP-C343 synthesis and spectroscopy

General

We obtained all solvents and reagents from commercial sources and used as received. We obtained PEG-amine (Av. MW 2,000) from Laysan Bio. Inc. We synthesized PtP-(AG3OH)4(C343)5 as described previously.25, 31 We performed preparative GPC on S-X1 (Biorad) beads, using THF as a mobile phase. The system for oxygen titrations was described previously.32, 33 We performed time-resolved phosphorescence measurements using a phosphorometer constructed in-house,34 modified for time-domain operation.

Synthesis of the PtP-C343 modified with PEG-amines (Av. MW 2,000)

Carboxy-terminated porphyrin-dendrimer PtP(AG3OH)4(C343)5 (107 mg, 0.012 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (10 ml). We heated the mixture for several minutes (~5–10 min) with a heat gun in the dark under argon flow and then allowed it to cool down to the room temperature. Stirring continued until the dendrimer appeared fully dissolved. We added HBTU (182 mg, 0.48 mmol) in one portion and stirred the mixture for 5 min. We added DIPEA (0.146 ml, 0.84 mmol) in one portion by a syringe, immediately followed by the addition of mPEG-NH2, Av. MW 2,000 (960 mg, 0.48 mmol) in DMF (5 ml). The mixture was protected from ambient light and left stirring for 2 days.

We added ether (~30 ml) to the reaction mixture, leading to the formation of brightly colored oil while leaving the mother liquor colorless. The oil was separated by centrifugation, dissolved in THF, separated again by the addition of ether and centrifugation. This procedure was repeated two more times to remove most of the unreacted amino-PEG. We achieved the final purification by size-exclusion chromatography using THF as a solvent. The brown band was collected, the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation and the probe was briefly dried in vacuum. We dissolved this in a small amount of distilled water (~5 ml), filtered it through a PTFE syringe filter (0.2 µm pore diameter), and freeze-dried it on a lyophilizer. The probe was isolated as brown solid material (yield: 86%).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank W. Wu for the rat surgery, C. Ayata and G. Boas for critically reading the manuscript, and support from National Institute of Health grants R01NS057476, P50NS010828, P01NS055104, R01EB000790, K99NS067050, R01HL081273, R01EB007279, and American Heart Association grant 0855772D.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.S., M.A.Y., and V.J.S. designed the microscope. E.R. synthesized the probe. S.S., M.A.Y., E.T.M., A.D., K.A., and S.R. performed experiments. S.S., D.A.B., and S.A.V. analyzed the data. D.A.B., S.A.V., E.H.L., S.S., and A.D. conceptualized and directed the research project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Editorial Summaries

AOP: Two-photon excitation of a phosphorescent nanoprobe that is quenched by molecular oxygen permits high-resolution measurements of oxygen in both the vasculature and tissue of rodent brain.

Issue: Two-photon excitation of a phosphorescent nanoprobe that is quenched by molecular oxygen permits high-resolution measurements of oxygen in both the vasculature and tissue of rodent brain.

References

- 1.Heeger DJ, Ress D. What does fMRI tell us about neuronal activity? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:142–151. doi: 10.1038/nrn730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iadecola C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:347–360. doi: 10.1038/nrn1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takano T, et al. Cortical spreading depression causes and coincides with tissue hypoxia. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:754–762. doi: 10.1038/nn1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erecinska M, Silver IA. Tissue oxygen tension and brain sensitivity to hypoxia. Respir. Physiol. 2001;128:263–276. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vovenko E. Distribution of oxygen tension on the surface of arterioles, capillaries and venules of brain cortex and in tissue in normoxia: an experimental study on rats. Pflugers Arch. 1999;437:617–623. doi: 10.1007/s004240050825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masamoto K, Takizawa N, Kobayashi H, Oka K, Tanishita K. Dual responses of tissue partial pressure of oxygen after functional stimulation in rat somatosensory cortex. Brain Res. 2003;979:104–113. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02882-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharan M, Vovenko EP, Vadapalli A, Popel AS, Pittman RN. Experimental and theoretical studies of oxygen gradients in rat pial microvessels. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1597–1604. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon GR, Choi HB, Rungta RL, Ellis-Davies GC, MacVicar BA. Brain metabolism dictates the polarity of astrocyte control over arterioles. Nature. 2008;456:745–749. doi: 10.1038/nature07525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koch CJ. Measurement of absolute oxygen levels in cells and tissues using oxygen sensors and 2-nitroimidazole EF5. Methods Enzymol. 2002;352:3–31. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)52003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishna MC, et al. Overhauser enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for tumor oximetry: coregistration of tumor anatomy and tissue oxygen concentration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:2216–2221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042671399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swartz HM, Clarkson RB. The measurement of oxygen in vivo using EPR techniques. Phys. Med. Biol. 1998;43:1957–1975. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/43/7/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanzetta I, Grinvald A. Increased cortical oxidative metabolism due to sensory stimulation: implications for functional brain imaging. Science. 1999;286:1555–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang LV. Multiscale photoacoustic microscopy and computed tomography. Nature Photonics. 2009;3:503–509. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2009.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu D, Matthews TE, Ye T, Piletic IR, Warren WS. Label-free in vivo optical imaging of microvasculature and oxygenation level. J. Biomed. Opt. 2008;13:040503. doi: 10.1117/1.2968260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanderkooi JM, Maniara G, Green TJ, Wilson DF. An optical method for measurement of dioxygen concentration based upon quenching of phosphorescence. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:5476–5482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mik EG, Johannes T, Ince C. Monitoring of renal venous pO2 and kidney oxygen consumption in rats by a near-infrared phosphorescence lifetime technique. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F676–F681. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00569.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres Filho IP, Intaglietta M. Microvessel pO2 measurements by phosphorescence decay method. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:H1434–H1438. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.4.H1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ances BM, Wilson DF, Greenberg JH, Detre JA. Dynamic changes in cerebral blood flow, O2 tension, and calculated cerebral metabolic rate of O2 during functional activation using oxygen phosphorescence quenching. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:511–516. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200105000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastuszko A, et al. Effects of graded levels of tissue oxygen pressure on dopamine metabolism in the striatum of newborn piglets. J. Neurochem. 1993;60:161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb05834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shonat RD, Wachman ES, Niu W, Koretsky AP, Farkas DL. Near-simultaneous hemoglobin saturation and oxygen tension maps in mouse brain using an AOTF microscope. Biophys. J. 1997;73:1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78155-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golub AS, Pittman RN. pO2 measurements in the microcirculation using phosphorescence quenching microscopy at high magnification. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;294:H2905–H2916. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01347.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denk W, Strickler JH, Webb WW. Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science. 1990;248:73–76. doi: 10.1126/science.2321027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Estrada AD, Ponticorvo A, Ford TN, Dunn AK. Microvascular oxygen quantification using two-photon microscopy. Opt. Lett. 2008;33:1038–1040. doi: 10.1364/ol.33.001038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mik EG, van Leeuwen TG, Raat NJ, Ince C. Quantitative determination of localized tissue oxygen concentration in vivo by two-photon excitation phosphorescence lifetime measurements. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004;97:1962–1969. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01399.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finikova OS, et al. Oxygen microscopy by two-photon-excited phosphorescence. Chemphyschem. 2008;9:1673–1679. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200800296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebedev AY, et al. Dendritic phosphorescent probes for oxygen imaging in biological systems. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2009;1:1292–1304. doi: 10.1021/am9001698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Padnick LB, Linsenmeier RA, Goldstick TK. Oxygenation of the cat primary visual cortex. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999;86:1490–1496. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.5.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu S, Maslov K, Tsytsarev V, Wang LV. Functional transcranial brain imaging by optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009;14:040503. doi: 10.1117/1.3194136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srinivasan VJ, et al. Depth-resolved microscopy of cortical hemodynamics with optical coherence tomography. Opt. Lett. 2009;34:3086–3088. doi: 10.1364/OL.34.003086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang Q, et al. Oxygen advection and diffusion in a three-dimensional vascular anatomical network. Opt. Express. 2008;16:17530–17541. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.17530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lebedev AY, Troxler T, Vinogradov SA. Design of metalloporphyrin-based dendritic nanoprobes for two-photon microscopy of oxygen. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines. 2008;12:1261–1269. doi: 10.1142/S1088424608000649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rozhkov V, Wilson DF, Vinogradov SA. Phosphorescent Pd porphyrin-dendrimers: Tuning core accessibility by varying the hydrophobicity of the dendritic matrix. Macromolecules. 2002;35:1991–1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khajehpour M, et al. Accessibility of oxygen with respect to the heme pocket in horseradish peroxidase. Proteins. 2003;53:656–666. doi: 10.1002/prot.10475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vinogradov SA, Fernandez-Searra MA, Dugan BW, Wilson DF. Frequency domain instrument for measuring phosphorescence lifetime distributions in heterogeneous samples. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2001;72:3396–3406. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.