Abstract

Background

Dronedarone is FDA approved for the treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) as a safe alternative to amiodarone. There are no full-length published papers describing the effectiveness of acute dronedarone against AF in experimental or clinical studies.

Methods

We determined the effect of acute dronedarone and amiodarone on electrophysiological parameters, and their anti-AF efficacy in canine isolated arterially-perfused right atria. Transmembrane action potentials and pseudo-ECGs were recorded. Acetylcholine (ACh, 1.0 μM) was used to induce persistent AF.

Results

Amiodarone-induced changes were much more pronounced than those of dronedarone on a) action potential duration (ΔAPD90, +51±17 vs. 4±6 ms, p>0.01), b) effective refractory period (ΔERP +84±23 vs. 18±9 ms, p<0.001), c) diastolic threshold of excitation (ΔDTE, +0.32±0.11 vs. 0.03±0.02 mA, p<0.001), and d) Vmax (ΔVmax:−43±14 vs. −11±4%, p<0.01, n=5–6; all recorded at 10 μM, CL = 500 ms). Persistent AF was induced in 10/10 atria exposed to ACh alone; subsequent addition of dronedarone or amiodarone terminated AF in 1/7 and 4/5 atria, respectively. Persistent ACh-mediated AF was induced in 5/6 and 0/5 atria pretreated with dronedarone and amiodarone, respectively.

Conclusions

The electrophysiological effects and anti-AF efficacy of acute dronedarone are much weaker than those of amiodarone in a canine model of AF. The efficacy of acute dronedarone to prevent induction of acetylcholine-mediated AF as well as to terminate persistent AF in canine right atria is relatively poor. Our data suggest that acute dronedarone is a poor substitute for amiodarone for acute cardioversion of AF or prevention of AF recurrence.

INTRODUCTION

Currently available drugs for rhythm control of atrial fibrillation (AF) are far from optimal from the standpoint of efficacy and safety.1,2 Amiodarone remains the most effective anti-AF agents for the long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm, but its long-term use is often associated with extracardiac toxicity. Dronedarone is an amiodarone derivative that lacks the iodine moiety which is believed to be responsible for the toxicity of amiodarone. Available data indicate that long-term use of dronedarone is generally safer than that of amiodarone, but that its efficacy to maintain sinus rhythm is considerably lower than that of amiodarone.3,4

While several clinical trials report an anti-AF effect of dronedarone for long term maintenance of sinus rhythm,5,6 there are no full-length papers evaluating the effectiveness of acute dronedarone against AF in experimental or clinical studies. The main objective of the current study was to directly compare the acute electrophysiological effects of dronedarone and amiodarone, and their anti-AF potency in a canine model of AF.

METHODS

Dogs weighing 20–25 kg were anticoagulated with heparin (200 IU/kg) and anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (35 mg/kg, i.v.). The chest was opened via a left thoracotomy, the heart excised, placed in a cardioplegic solution consisting of cold (4°C) Tyrode’s solution containing 8.5 mM [K+]o and transported to a dissection tray. Three-fourths of both ventricles were quickly removed. The ostium of the right coronary artery was cannulated with polyethylene tubing (i.d., 1.75 mm; o.d., 2.1 mm) and the preparation was perfused with cold Tyrode’s solution (12 to 15°C) containing 8.5 mM [K+]0. With continuous coronary perfusion, all ventricular branches of the right coronary artery were immediately clamped with metal clips. The entire right atrium (RA) with a thin rim (<1 cm) of right ventricular tissue was carefully dissected from the remaining tissues and then the preparation was unfolded. Ventricular right coronary branches as well as the cut atrial branches were ligated using silk thread. The preparation was placed in a temperature-controlled bath (8 × 6 × 3 cm) and perfused at a rate of 8 to 10 mL/min with Tyrode’s solution (in mM): NaCl 129, KCl 4, NaH2PO4 0.9, NaHCO3 20, CaCl2 1.8, MgSO4 0.5, and D-glucose 5.5, buffered with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. (37.0±0.5°C).

Electrophysiological assessments

Transmembrane action potential (AP) recordings were obtained using floating glass microelectrodes (2.7 M KCl, 10 to 25 MΩ DC resistance) connected to a high input impedance amplification system (WPI, FL). The signals were displayed on oscilloscopes, amplified, digitized and analyzed (Spike 2, Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, England). An electrocardiogram (pseudo-ECG) was recorded using two electrodes consisting of AgCl half cells attached to Tyrode’s-filled tapered polyethylene electrodes which were placed in the bath solution 1.0 to 1.2 cm from the opposite ends of the preparations. The diastolic threshold of excitation (DTE) was determined by increasing stimulus intensity in 0.01 mA steps. The effective refractory period (ERP) was measured by delivering premature stimuli after every 10th regular beat at a pacing cycle length (CL) of 500 ms (with 5 to 10 ms resolution; stimulation with a 2 x DTE amplitude). Post-repolarization refractoriness (PRR) was defined as the difference between ERP and action potential duration at 70% repolarization (APD70; note that ERP corresponds to APD70–75 in atria).7, 8 Maximum rate of rise of the AP upstroke (Vmax): Stable AP recordings and Vmax measurements are difficult to obtain in vigorously contracting perfused preparations. A large variability in VMax measurements is normally encountered at any given condition, primarily due to variability in the amplitude of phase 0 of the AP which strongly determines VMax values. The effects of amiodarone and dronedarone on Vmax were determined by comparing the largest Vmax recorded under any given condition. Due to a substantial inter-preparation variability, Vmax values were normalized for each experiment and then averaged. Changes in conduction time were approximated by measuring the duration of the “P wave” complex on the ECG at a level representing 10% of the “P wave” amplitude.

Experimental protocols

Coronary-perfused atrial preparations were equilibrated in the tissue bath until electrically stable, usually 30 min. The preparations were paced at a CL of 500 ms, using a pair of thin silver electrodes insulated except at their tips (bipolar rectangular pulses of 2 ms duration and twice DTE intensity). APs were recorded under baseline conditions and after the addition of 5 and 10 μM of the agents to the perfusate. At least 30 min were allowed for each concentration of dronedarone and amiodarone to act before the start of data collection.

The anti-AF efficacy of the drugs was compared in an acetylcholine (ACh)-mediated model of persistent AF. Persistent AF develops in 100% of atrial preparations pretreated with ACh following burst pacing or introduction of a single extrastimuli.7,9 Two separate sets of experiments were performed. In the first set, ACh was added to the solution containing 10 μM dronedarone or amiodarone and programmed stimulation applied in an attempt to induce AF. In the second set, persistent AF was induced first (in the presence of ACh, 1.0 μM) and then, on the 4–6th min of on-going AF, dronedarone or amiodarone was added (10.0 μM) to the perfusate in the continued presence of ACh. If AF was terminated, re-induction of the arrhythmia was attempted.

Drugs

Dronedarone and amiodarone (dissolved in 100% dimethylsulfoxide [DMSO]) and ACh (dissolved in distilled water) were prepared fresh as a stock of 10 mM before each experiment.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using paired or unpaired Student’s t test and one way repeated measures or multiple comparison analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s test, as appropriate. All data are expressed as mean±SD.

RESULTS

Electrophysiological effects of dronedarone vs. amiodarone

Amiodarone but not dronedarone prolonged APD90 (Fig. 1). Dronedarone and amiodarone caused no significant change in APD70 (−Δ2±5 and +Δ3±7, respectively), but both abbreviated the APD50 (−Δ24±8 and −Δ21±9 ms, respectively; both p<0.05 vs. control, n=5–6, in CT, 10 μM; CL = 500 ms). Both drugs prolonged ERP but amiodarone prolonged it to a much greater extent than dronedarone (Fig. 1). The greater prolongation of ERP by amiodarone was due largely to a much greater development of PRR (81±15 vs. and 20±8 ms with amiodarone vs. dronedarone, respectively; p<0.001; n=5–6; in CT, 10 μM; CL = 500 ms).

Figure 1. Effects of acute amiodarone and dronedarone on repolarization and ERP in canine atria.

A: Superimposed action potentials showing the difference on the effects of dronedarone and amiodarone. B: Average changes in APD90 and ERP induced by dronedarone and amiodarone. All data were obtained from crista terminalis. *- p<0.05 vs. control; † - p<0.05 vs. respective dronedarone values. CL = 500 ms. n=5–7.

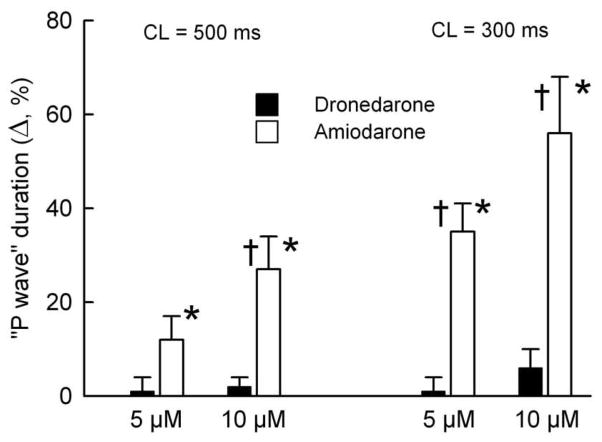

Depression of Vmax was also much greater with amiodarone than with dronedarone (Fig 2). Other sodium channel-mediated parameters (DTE, conduction time, and the shortest S1–S2 interval) were altered to a much greater extent by amiodarone than by dronedarone (Fig. 3–4, Table 1). Depression of Vmax, DTE, and slowing of conduction were all accentuated following acceleration of pacing rate when amiodarone was present, but not in the presence dronedarone. This is likely due in part to a significant reduction or elimination of the diastolic interval by amiodarone but not by dronedarone, which is secondary to the prolongation of the terminal part of phase 3 of the action potential by amiodarone, but not dronedarone (Fig. 2). Following acceleration of pacing rate from a CL of 500 to 300 ms, take-off potential was elevated by 1.2±0.6, 1.5±0.9, and 4.7±1.7% in the absence of drugs and in the presence of 10 μM dronedarone and amiodarone, respectively (normalized to phase 0 amplitude at a CL of 500 ms; measured on the 15th beat after acceleration; p<0.05 amiodarone vs. dronedarone and control, n=5–7).

Figure 2. Amiodarone produces a much greater use-dependent reduction of maximum rate of rise of the AP upstroke (Vmax) compared to that induced by dronedarone.

A: Transmembrane action potentials and respective Vmax values recorded upon shortening of cycle length (CL) from 500 to 300 ms. B: Summary data of the effects of dronedarone and amiodarone on Vmax in atrial preparations. All data are normalized to control Vmax value recorded at a CL of 500 ms. All reported data were obtained from the crista terminalis. *- p<0.05 vs. respective controls (C), † - p<0.05 vs. respective dronedarone’s values. n=5–7.

Figure 3.

Amiodarone but not dronedarone causes an increase in diastolic threshold of excitation (DTE) in atria. *- p<0.05 vs. respective controls; † - p<0.05 vs. respective dronedarone’s data. Cycle length (CL) = 500 ms. n=5–7. DTE data were obtained in pectinate muscle region.

Figure 4.

Conduction time was increased by amiodarone but not dronedarone. *- p<0.05 vs. respective controls; † - p<0.05 vs. dronedarone data. n=5–7.

Table 1.

Effects of dronedarone and amiodarone (both at 10 μM) to suppress atrial excitability and the induction of acetylcholine (ACh, 1 μM)-mediated persistent AF in the isolated canine coronary perfused right atria.

| APD70 (ms) | ERP (ms) | Shortest S1-S1 | Incidence of Persistent AF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 156±10 | 151±10 | 132±13 | 0% (0/10) |

| Dronedarone | 150±11 | 168±13* | 147±15 | 0% (0/10) |

| Amiodarone | 169±16*‡ | 234±21*‡ | 291±28*‡ | 0% (0/5) |

| ACh | 40±6 | 48±9 | 54±9 | 100% (10/10) |

| Dronedarone ACh + | 50±7 | 62±6 | 88±13† | 83% (5/6) |

| Amiodarone +ACh | 112±15†# | 135±23†# | 189±37†# | 0% (0/5) |

APD and ERP data presented in the table were obtained from the pectinate muscle region of coronary-perfused atria at a CL of 500 ms (n=5–7). Shortest S1-S1- the shortest CL permitting 1:1 activation (at a DTE x 2 determined at a CL of 500 ms).

p< 0.05 vs. control;

P< 0.05 vs. acetylcholine alone (ACh, 1.0 μM).

- p< 0.05 vs. dronedarone dronedarone’s values.

- p< 0.05 vs. Dronedarone + ACh.

Anti-AF efficacy of dronedarone vs. amiodarone

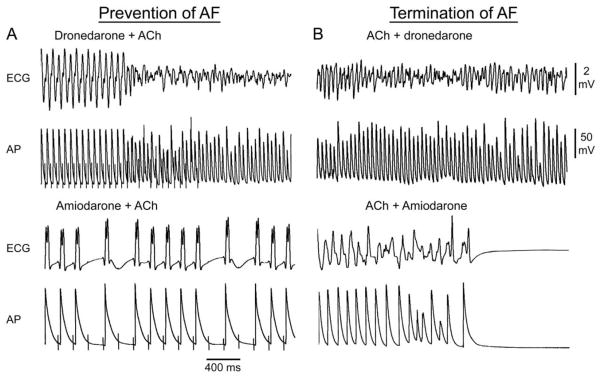

ACh significantly abbreviated APD and ERP permitting induction of persistent AF in 10/10 of atria (Table 1). Termination of AF once induced, as well as the effect to prevent the induction of persistent ACh-mediated AF, were much greater with amiodarone than with dronedarone (Fig. 5; Table 1 and 2). The anti-AF efficacy of acute dronedarone was very poor in the vagally-mediated AF model. The striking difference in the anti-AF efficacy of amiodarone vs. dronedarone was consistent with the much greater effect of amiodarone on various electrophysiological parameters including APD90, ERP, and the shortest S1-S1 in the presence of ACh (Table 1 and Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Anti-AF efficacy of acute dronedarone is inferior to that of amiodarone in coronary-perfused canine right atria. Each of the four panels shows simultaneously recorded ECG and action potential (AP) tracings. A: Induction of ACh-mediated AF by rapid pacing in the presence of dronedarone (10 μM) and failure of pacing to induce AF in the presence of amiodarone (10 μM), due to depression of excitability and prolongation of APD. B: Failure of dronedarone (10 μM) to abort persistent ACh-mediated AF and termination of AF by amiodarone (10 μM).

Table 2.

Effects of dronedarone and amiodarone (both at 10 μM) to terminate persistent acetylcholine (ACh 1 μM)-mediated AF and prevent its re-induction in the isolated canine coronary perfused right atria

| Termination of Persistent AF | Prevention of AF recurrence | |

|---|---|---|

| ACh | 0% (0/10) | - |

| ACh + Dronedarone | 14% (1/7) | 0% (0/1) |

| ACh + Amiodarone | 80% (4/5) | 100% (4/4) |

DISCUSSION

The main results of the present study are that electrophysiological effects and anti-AF efficacy of acute dronedarone are much weaker than those of amiodarone in coronary-perfused canine right atria.

Electrophysiological effects of dronedarone and amiodarone

There are important atrioventricular differences in the response to INa and IKr blockers.7, 10 Comparison of our data with prior studies involving amiodarone and dronedarone is hampered by the fact that the majority of previous studies were carried out in ventricular tissues. Moreover, all Vmax and APD data were recorded from superfused cardiac preparations in which electrophysiological parameters are depressed, and pharmacological responsiveness is generally blunted.11 In superfused ventricular preparations, acute dronedarone and amiodarone have been reported to produce variable results, but generally either no or small changes in APD.12–15 In the only study known to us in which acute dronedarone and amiodarone were directly compared in atria, both agents abbreviated APD90 to a similar extent in rabbit superfused atrial preparations.16 Both acute amiodarone and dronedarone abbreviated ERP in rabbit superfused atrial preparations,16 but prolonged it in atria of in in vivo dogs.17 In a direct comparison, acute dronedarone and amiodarone (10 μM) were reported to cause either small or no reduction in Vmax (≤15%) in atrial (rabbit)16 and ventricular (rabbit, guinea pig, and dog) superfused preparations.12–14 Acute amiodarone was shown to exert a greater reduction in Vmax than dronedarone in canine Purkinje fibers,12 similar to the results we report here for canine atria (Fig. 2).

Our study is the first demonstrating the induction of PRR by amiodarone but not dronedarone in a direct comparison. The induction of PRR with amiodarone has been shown previously.10,18,19 PRR is believed to be an important factor in the antiarrhythmic efficacy of amiodarone.10,18,19 We are not aware of any study showing the induction of PRR with dronedarone.

The ion channel block profile of amiodarone and dronedarone are similar, but not identical. Both agents inhibit IKr, IKs, early INa, ICa-L, Ito, IK-Ach as well as β and α receptors.20 In one previous study, dronedarone was reported to be a more potent blocker of early INa in human isolated atrial myocytes.21 This finding however is at odds with a number of studies in which Vmax was shown to be equally depressed or not affected by the two drugs (in canine, rabbit, guinea pig cardiac muscle superfused preparations)12–14, 16 or in which a greater reduction in Vmax was observed with amiodarone (in canine Purkinje fibers12 and coronary-perfused atria, Fig. 2). It has also been reported that acute dronedarone is a 100 times more potent inhibitor of IK-Ach than amiodarone in rabbit atrial myocytes.22 This finding is inconsistent with our data showing a slight effect of dronedarone to prolong atrial APD in the presence of ACh (Table 1).

Clinical relevance of the concentrations of amiodarone and dronedarone used

The purpose of our study was to compare acute electrophysiological and anti-AF effects of dronedarone and amiodarone. Although therapeutically relevant plasma concentration of both agents can be achieved within several hours of acute administration, the full effect of amiodarone’s actions are known to be considerably delayed compared to those of dronedarone. With chronic dosing, the steady-state therapeutic peak plasma concentration (Cmax) of oral amiodarone is known to be greater than that of dronedarone (up to 3.1 vs. 0.263 μM, respectively). When first initiated, oral dosing of amiodarone and dronedarone is similar (400 mg twice a day for dronedarone and amiodarone). The time to peak plasma concentration (Tmax) is comparable for dronedarone and amiodarone (3–7 hours), but bioavailability of amiodarone is greater than that of dronedarone (approximately 50 vs. 15%) and elimination rate is much slower for amiodarone. Thus, peak or average plasma concentration of amiodarone is expected to be greater than that of dronedarone following acute administration. In the present study, as in all of previously-published acute in vitro studies,12–14,16 we used equal concentrations of these agents (5 and 10 μM). Despite this apparent bias “favoring” dronedarone, amiodarone was found to produce much more potent electrophysiological changes and was thus more effective in suppressing AF. The selection of relatively high concentrations of the two agents in our investigation stemmed from the fact that even at concentrations of 5–10 μM, dronedarone produced little to no change in atrial electrophysiology. It should be stressed that pharmacokinetics and drug sensitivity of Tyrode’s-perfused canine isolated atrial preparations may be very different from those encountered in the clinic (see Limitation of the Study section).

Anti-AF efficacy of dronedarone and amiodarone

The anti-AF efficacy of acute dronedarone was much weaker than that of amiodarone in our study. While amiodarone is widely used for long-term prevention of AF recurrence, this drug is also commonly administered for acute cardioversion of paroxysmal AF (Class IIa, level of evidence: A).23 To the best of our knowledge, there are no previously published full-length papers evaluating the efficacy of acute dronedarone against AF in experimental or clinical studies. In two abstracts published in 1998 and 2001, acute dronedarone was reported to be more effective than acute amiodarone against vagally-mediated AF in dogs24 and against hypokalemia-induced AF in guinea pig.25 These data are in contrast to our findings as well as to the available clinical data demonstrating superiority of amiodarone vs. dronedarone for prevention of AF recurrence.3,4 In the DIONYSOS trial, which directly compared amiodarone and dronedarone, the rate of recurrence of AF at 6 months of follow-up was 63% with dronedarone and 42% with amiodarone.4 AF recurrence was registered in 64% of patients treated with dronedarone vs. 75% patients taking placebo at 1 year follow-up in the combined EURIDIS and ADONIS trials.6

Primary goals in AF therapy and the role of dronedarone

Clinical data suggest that while dronedarone is less effective than amiodarone for the management of AF, it is generally safer than amiodarone.3,4 Both agents, however, may increase mortality in patients with advanced heart failure.26,27 Dronedarone was recently approved by the FDA largely on the basis of the results of the ATHENA trial for reducing hospitalization of AF patients without severe heart failure (not for AF reduction).28 The large ATHENA trial demonstrated a significant reduction in the primary endpoint in AF patients treated with dronedarone (i.e., cardiovascular-related hospitalization and mortality).28 There was a non-significant trend in all-cause mortality in the dronedarone vs. placebo groups of ATHENA (p=0.18) and a significant reduction of mortality from cardiovascular causes (p=0.03). The positive outcomes of the ATHENA trial are likely due to a combination of a slowing of ventricular rate, a reduction of stroke, acute coronary syndrome, blood pressure, as well as AF.6,28,29 The contribution of AF reduction to the overall positive outcome in ATHENA is difficult to determine because AF burden (such as AF recurrence, time to first AF recurrence, AF duration, etc) was not obtained. Considering the modest long-term anti-AF efficacy of dronedarone reported in previous studies,4–6 it seems that the reduction in cardiovascular-related hospitalization and mortality can be achieved without a major suppression of AF.

Improvement of morbidity and mortality is the optimal goal of pharmacological therapy in patients with AF. The choice of rhythm control therapy with antiarrhythmic drugs (AAD), if selected over other options, must consider both efficacy and safety outcomes, which is a major challenge to predict.1,30 This is in part due to the fact that AF in most patients co-exists with other, often more serious diseases, including CHF, hypertension and myocardial infarction which may significantly alter AAD efficacy and safety. Pharmacological strategies targeting both intra- and extracardiac factors associated with AF, particularly those possessing rate control and stroke protection capabilities are desirable for reducing morbidity and mortality of AF patients. Dronedarone has been shown to possess a number of intra- and extracardiac positive actions (listed above),6,28,29 contributing to reduction of morbidity and cardiovascular related-mortality of patients with AF patients. It is not known whether dronedarone is superior to the other anti-AF agents in this respect.31 It is known that amiodarone and sotalol have ventricular rate control effects.23 It has been shown that dofetilide reduces hospitalization of AF patients with CHF and amiodarone decreases death from ventricular arrhythmia in patients with myocardial infarction, both without reducing all-cause mortality.32–34 Of note, all-cause mortality has not been shown to be reduced by any anti-AF agent in large clinical trials conducted to the date.6,23,28,35,36

Limitation of the study

Our experiments were conducted in isolated Tyrode’s perfused canine atrial preparations, lacking exogenous autonomic influences, hormones, and other blood-related factors, which may modify pharmacological in vivo responses. Another important limitation is that we used non-remodeled atria, while clinical AF is commonly associated with structural and electrical abnormalities, which may also significantly modify atrial electrophysiological responses to AADs as well as alter anti-AF actions. Although the vagally-mediated AF model used in the present study does not recapitulate all forms of clinical AF, the anti-AF efficacy of AADs previously studied using this model, including amiodarone, propafenone, lidocaine, and sotalol, is consistent with the efficacy of these agents in the clinic.7,10

Conclusions

This is the first full-length paper that compares anti-AF efficacy of acute dronedarone and amiodarone in either experimental or clinical studies. The results of the current study clearly indicate that the acute electrophysiological effects and anti-AF potency of dronedarone are much weaker than those of acute amiodarone.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Judy Hefferon and Robert Goodrow.

Supported by grant HL47678 from NHLBI (CA) and the Masonic Grand Lodges of New York State and Florida.

FUNDING SOURCES: This study was supported by grants from Gilead Sciences, Inc. (CA), NIH (HL-47687, CA), and the New York State and Florida Grand Lodges of Free and Accepted Masons.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Antzelevitch received research support and is a consultant to Gilead Sciences. Dr. Belardinelli is an employee of Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Prystowsky EN. Atrial fibrillation: Dronedarone and amiodarone-the safety versus efficacy debate. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:5–6. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. New development in atrial antiarrhythmic drug therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:139–48. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piccini JP, Hasselblad V, Peterson ED, et al. Comparative efficacy of dronedarone and amiodarone for the maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1089–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barquet P. DIONYSOS study results showed the respective profile of dronedarone and amiodarone. 2008 en.sanofi-aventis.com/binaries/20081223_dionysos_fe_en_en_tcm28-23624.pdf.

- 5.Touboul P, Brugada J, Capucci A, et al. Dronedarone for prevention of atrial fibrillation: a dose-ranging study. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1481–7. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh BN, Connolly SJ, Crijns HJ, et al. Dronedarone for maintenance of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation or flutter. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:987–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Zygmunt AC, et al. Atrium-selective sodium channel block as a strategy for suppression of atrial fibrillation: differences in sodium channel inactivation between atria and ventricles and the role of ranolazine. Circulation. 2007;116:1449–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bode F, Kilborn M, Karasik P, et al. The repolarization-excitability relationship in the human right atrium is unaffected by cycle length, recording site and prior arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:920–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burashnikov A, Antzelevitch C. Reinduction of atrial fibrillation immediately after termination of the arrhythmia is mediated by late phase 3 early afterdepolarization-induced triggered activity. Circulation. 2003;107:2355–60. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065578.00869.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Sicouri S, et al. Atrial-selective effects of chronic amiodarone in the management of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1735–42. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burashnikov A, Mannava S, Antzelevitch C. Transmembrane action potential heterogeneity in the canine isolated arterially-perfused atrium: effect of IKr and Ito/IKur block. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:H2393–H2400. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01242.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varro A, Takacs J, Nemeth M, et al. Electrophysiological effects of dronedarone (SR 33589), a noniodinated amiodarone derivative in the canine heart: comparison with amiodarone. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:625–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gautier P, Guillemare E, Marion A, et al. Electrophysiologic characterization of dronedarone in guinea pig ventricular cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;41:191–202. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200302000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun W, Sarma JS, Singh BN. Electrophysiological effects of dronedarone (SR33589), a noniodinated benzofuran derivative, in the rabbit heart: comparison with amiodarone. Circulation. 1999;100:2276–81. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.22.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moro S, Ferreiro M, Celestino D, et al. In vitro effects of acute amiodarone and dronedarone on epicardial, endocardial, and M cells of the canine ventricle. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2007;12:314–21. doi: 10.1177/1074248407306906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun W, Sarma JS, Singh BN. Chronic and acute effects of dronedarone on the action potential of rabbit atrial muscle preparations: comparison with amiodarone. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2002;39:677–84. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200205000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manning A, Thisse V, Hodeige D, et al. SR 33589, a new amiodarone-like antiarrhythmic agent: electrophysiological effects in anesthetized dogs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;25:252–61. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elizari MV, Levi RJ, Novakosky A, et al. Cellular effects of antiarrhythymic drugs. Remarks on methodology. VIII European of Cardiology. 1980:11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirchhof P, Degen H, Franz MR, et al. Amiodarone-induced postrepolarization refractoriness suppresses induction of ventricular fibrillation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:257–63. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel C, Yan GX, Kowey PR. Dronedarone. Circulation. 2009;120:636–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.858027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalevee N, Nargeot J, Barrere-Lemaire S, et al. Effects of amiodarone and dronedarone on voltage-dependent sodium current in human cardiomyocytes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:885–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guillemare E, Marion A, Nisato D, et al. Inhibitory effects of dronedarone on muscarinic K+ current in guinea pig atrial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;36:802–5. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200012000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:854–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finance O, Planchenault J, Bethegnies S, et al. Electrophysiological and anti-arrhythmic actions of a new-amiodarone-like agent, dronedarone in experimental atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:A251. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cosnier-Pucheu S, Guiraudou P, Rizzoli G, et al. Effects of amiodarone and dronedarone in the prevention of atrial arrhythmias in guinea pig isolated heart. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2001;94:21. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, McMurray JJ, et al. Increased mortality after dronedarone therapy for severe heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2678–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hohnloser SH, Crijns HJ, van EM, et al. Effect of dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:668–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connolly SJ, Crijns HJ, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. Analysis of stroke in ATHENA: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-arm trial to assess the efficacy of dronedarone 400 mg BID for the prevention of cardiovascular hospitalization or death from any cause in patients with atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter. Circulation. 2009;120:1174–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.875252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirchhof P, Bax J, Blomstrom-Lundquist C, et al. Early and comprehensive management of atrial fibrillation: proceedings from the 2nd AFNET/EHRA consensus conference on atrial fibrillation entitled ‘research perspectives in atrial fibrillation’. Europace. 2009;11:860–85. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Falk RH, Camm AJ. Rethinking the reasons to treat atrial fibrillation? The role of dronedarone in reducing cardiovascular hospitalizations. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2438–40. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedersen OD, Bagger H, Keller N, et al. Efficacy of dofetilide in the treatment of atrial fibrillation-flutter in patients with reduced left ventricular function: a Danish investigations of arrhythmia and mortality on dofetilide (diamond) substudy. Circulation. 2001;104:292–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Julian DG, Camm AJ, Frangin G, et al. Randomised trial of effect of amiodarone on mortality in patients with left-ventricular dysfunction after recent myocardial infarction: EMIAT. European Myocardial Infarct Amiodarone Trial Investigators. Lancet. 1997;349:667–74. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cairns JA, Connolly SJ, Roberts R, et al. Randomised trial of outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with frequent or repetitive ventricular premature depolarisations: CAMIAT. Canadian Amiodarone Myocardial Infarction Arrhythmia Trial Investigators. Lancet. 1997;349:675–82. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)08171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lafuente-Lafuente C, Mouly S, Longas-Tejero MA, et al. Antiarrhythmics for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD005049. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005049.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torp-Pedersen C, Moller M, Bloch-Thomsen PE, et al. Dofetilide in patients with congestive heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction. Danish Investigations of Arrhythmia and Mortality on Dofetilide Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:857–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909163411201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]