Abstract

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is a highly lethal disease with complex etiology involving both environmental and genetic factors. While cigarette smoking is known to explain 25% of cases, data from recent studies suggest that obesity and long-term type II diabetes are two major modifiable risk factors for PC. Furthermore, obesity and diabetes appear to affect the clinical outcome of patients with PC. Understanding the mechanistic effects of obesity and diabetes on the pancreas may identify new strategies for prevention or therapy. Experimental and epidemiological evidence suggests that the antidiabetic drug metformin has protective antitumor activity in PC. In addition to insulin resistance and inflammation as mechanisms of carcinogenesis, obesity and diabetes are linked to impairments in endothelial function and coagulation status, which increase the risks of thrombosis and angiogenesis and in turn the risk of PC development and progression. The associations of the ABO blood group gene and NR5A2 gene variants with PC discovered by recent genome-wide association studies may link insulin resistance, inflammation, and thrombosis to pancreatic carcinogenesis. These exciting findings open new avenues for understanding the etiology of PC and provide opportunities for developing novel strategies for prevention and treatment of this disease.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, etiology, epidemiology, therapy

BACKGROUND

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death for both men and women in the U.S. It is one of the most lethal malignancies, with a 5-year survival rate of <5% and median survival duration of less than 6 months (1). According to the American Cancer Society, a total of 42,470 new cases and 35,270 deaths occurred in 2009. Worldwide, PC contributes to more than 230,000 deaths annually.

Cigarette smoking is the most consistently established risk factor for PC, contributing to 25% of cases. Other suspected risk factors include heavy alcohol consumption, chronic pancreatitis, and dietary/endocrine factors (2). As the prevalence of cigarette smoking decreases, and that of obesity and diabetes increases, the latter two are poised to become the major modifiable risk factors for PC in Western countries.

Obesity and Diabetes as Risk Factors for PC

Data on the association of obesity and PC were inconsistent in earlier studies, partially because of improper study design or small sample size. Several recent cohort and case-control studies have reported elevated risks of PC in obese individuals, compared with individuals of normal weight, with relative risks (RR) or odds ratios ranging from 1.2 to 3.0 (3). A recent meta-analysis of 21 independent prospective studies involving 3,495,981 individuals and 8,062 PC patients showed that the RR of PC per 5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index (BMI) was 1.16 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.06–1.17) in men and 1.10 (95% CI: 1.02–1.19) in women (4). It has been estimated that the population-attributable fraction of obesity-associated PC is 26.9% for the U.S. population (3).

Our recent study in 740 PC cases and 769 cancer-free controls found that overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2) at ages from 14–19 years to the 30s and obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) at ages from the 20s to the 40s were significantly associated with increased risk of PC, independent of diabetes (5). The risk leveled off for weight changes after age 40. The stronger association of the disease with weight gain in earlier adulthood than in later adulthood might be explained by the longer duration of exposure to cumulative excessive body fat in the earlier gainers. Because very few individuals overweight or obese at a younger age returned to a normal weight later in life, it is unknown whether the risk of PC could be reduced by successful weight control in middle age. Thus, weight control at younger ages should be one of the primary strategies for the prevention of PC.

Because diabetes is a manifestation of PC, a long-standing controversy exists over the role of type II diabetes in the etiology of this cancer. Examining the duration of diabetes prior to cancer was critical to understanding whether diabetes is a risk factor, in addition to being a consequence, of PC. A meta-analysis of 20 studies published in 1995 estimated that long-standing diabetes (5 years or more) increased PC risk 2-fold (RR, 2.0; 95% CI: 1.2–3.2) (6). In an updated meta-analysis based on 36 studies, the association between established diabetes and PC was slightly weaker than in the earlier meta-analysis but remained statistically significant (RR, 1.5; 95% CI: 1.3–1.8, and RR, 1.5; 95% CI: 1.2–2.0, for groups with 5–9 years or 10+ years of existing diabetes prior to cancer, respectively, compared to nondiabetic individuals) (7). When analyzed separately, results from cohort and case-control studies were similar (7), suggesting that bias is unlikely to explain the excess risk observed in these studies.

The direct relation between blood glucose levels and PC risk has been examined in prospective studies. Both fasting and postload serum glucose levels were significantly associated with increased risk of death from PC (8, 9). Results from these studies strongly support a causal role of type II diabetes in PC.

Obesity, Diabetes, and Clinical Outcome of PC

Our recent study found that obesity within a year of PC diagnosis was significantly associated with an average of 5 months shorter overall survival regardless of disease stage and tumor resection status (5). Several other clinical studies have also shown that patients with a higher BMI had worse clinical outcomes than those who had normal BMI (10–12). Although obesity is a risk factor for diabetes, the impact of obesity on PC survival was independent of diabetes (13).

These observations raise questions regarding the mechanisms that underlie the association between obesity and reduced patient survival. There are several possibilities through which obesity could contribute to a worse prognosis: 1) increased risk of diabetes, thrombosis, and other comorbid conditions; 2) impaired immune function and a more aggressive tumor type; and 3) poor response to therapy. Few studies have investigated these issues, and some of the observations that examined the association between diabetes and PC survival were inconsistent, depending on the populations studied. In general, it has been possible to show that diabetes had a negative effect on survival in patients with resected pancreatic tumors (14, 15) but not in patients with late-stage disease (16–18). A recent large meta-analysis found no association between long-term diabetes and survival in PC (19). Further research on the mechanisms of reduced PC survival in obese patients is required, and such efforts may lead to novel therapeutic targets.

ON THE HORIZON

Insulin-like Growth Factor

A recent study in an animal model of PC has shown that the same human PC cell line manifested dramatically different growth patterns in obese mice and in wild-type lean mice (20). In obese mice, tumors grew larger and faster, metastasized more frequently, and caused significantly greater mortality than tumors in lean animals. Rapid tumor growth was not a function of decreased apoptosis, but was related directly to increased cellular proliferation. Interestingly, tumor cell proliferation correlated negatively with the adipokine adiponectin and positively with serum insulin concentration. These observations provided evidence for the direct influence of obesity on PC growth and dissemination and suggested a role for insulin and adipokines in the process.

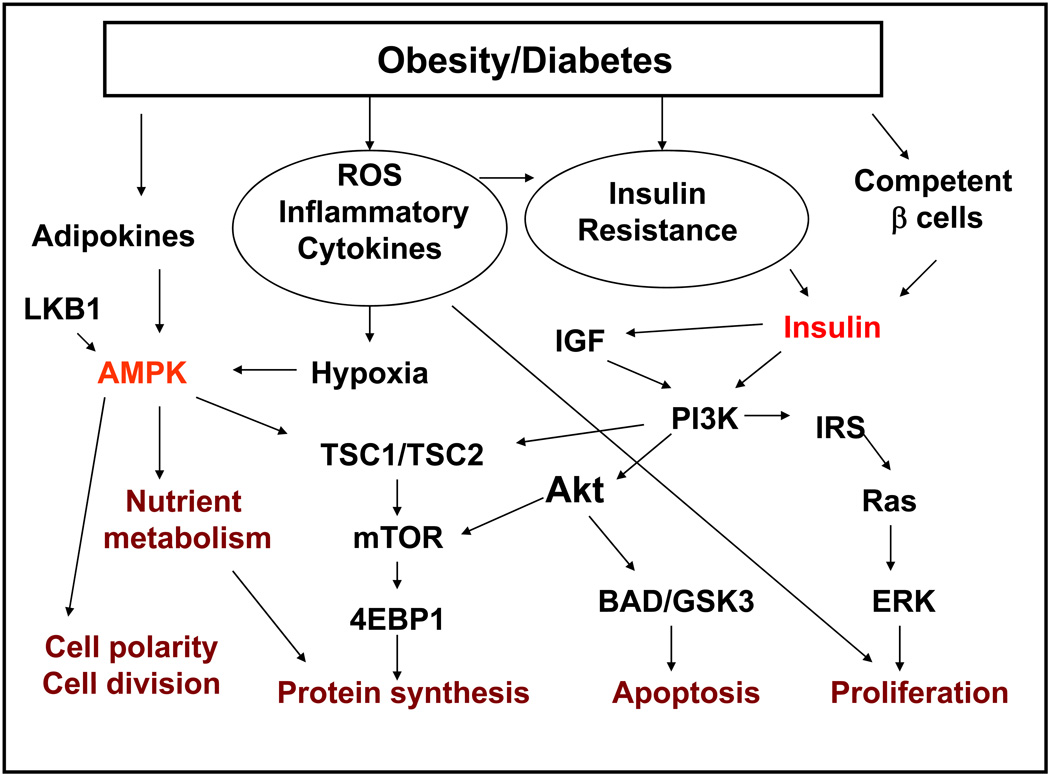

In obesity, the adipose tissue acts as an endocrine organ, regulating the release of free fatty acids, cytokines, and hormones. The complex interplay of these and other substances leads to insulin resistance and compensatory chronic hyperinsulinemia. Conceptually, the increased level of insulin and consequent higher levels of insulin-like growth factors (IGF) and other proinflammatory cytokines promote cell proliferation, inhibit apoptosis, and enhance angiogenesis, which lead to accelerated tumor development and progression (Fig. 1). Insulin and IGF-1 stimulate the mTOR pathway by activating the insulin receptor substrate-1 and the phosphatidylinositol–3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway (21). Insulin and IGF-1 signaling also integrates with the epidermal growth factor (EGF)/EGF receptor (22), c-Jun-NH2-kinase, and met proto-oncogene signaling pathways (23). Early experience with IGF-1 receptor blockade suggests that the IGF-1 signaling pathway may be an important therapeutic approach for PC. (24)

Fig. 1.

Contributions of obesity and diabetes to the development and progression of pancreatic cancer.

Nuclear Receptor 5A2

A recent genome-wide association study identified the nuclear receptor 5A2 (NR5A2) gene as a significant predisposing factor for PC (25). NR5A2 belongs to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, and is expressed mainly in the liver, intestine, exocrine pancreas, and ovary (26). It plays a crucial role in cholesterol metabolism and steroidogenesis. NR5A2 has been associated with colon and breast cancers through its functional interaction with the β-catenin/Tcf4 signaling pathway and its stimulation of the estrogen metabolic genes (27). In the pancreas, NR5A2 is a major downstream component of the pancreatic-duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX-1) regulatory complex governing pancreatic development, differentiation, and function (28). NR5A2 and PDX-1 are co-expressed in the pancreas during mouse embryonic development, but later NR5A2 expression becomes restricted to the murine exocrine pancreas (no human data are available).It has been suggested that NR5A2 is a component of a transcriptional network involving PDX-1 and hepatocyte nuclear factors HNF-1α, HNF-4α, and HNF-3β that regulates pancreatic development and may also play a role in pancreas homeostasis in the adult. Since several transcription factors either upstream or downstream of NR5A2 have been associated with development of diabetes (29), it has been speculated that NR5A2 contributes to diseases linked to pancreatic dysfunction, such as diabetes. Interestingly, the adiponectin gene promoter contains a NR5A2 response element, and NR5A2 plays an important role in transcriptional activation of the adiponectin gene (30). Adiponectin is an adipocyte-secreted hormone that has been proposed to be a biological link between obesity (especially central obesity) and increased risk of cancer (31), including PC (32). An NR5A2 gene variant has been associated with excess BMI in another genome-wide association study (33). Understanding the mechanism through which NR5A2 contributes to PC, especially obesity- or diabetes-associated PC, may identify novel targets for prevention and treatment.

Obesity, ABO, and Thrombosis

Obesity is a known risk factor for thrombosis. Thrombosis is a frequent complication of PC, with reported incidences ranging from 17% to 57% (34). Thromboembolic events usually are related to poor prognosis in patients with cancer. Other general risk factors for thrombosis in malignancy include retroperitoneal tumor location, decreased activity in bedridden patients, frequent hospitalizations, radiation injury to blood vessels, and hypercoagulability. Patients with PC are often in a hypercoagulable state with increased plasma levels of pro-coagulants, such as tissue factor, thrombin, and fibrinogen, and decreased levels of coagulation inhibitors, such as antithrombin III, heparin cofactor II, protein C, free protein S, and thrombomodulin (35). The hypercoagulable state can promote angiogenesis, inflammation, and development of metastasis. The potential mechanisms that link obesity and thrombosis with poor prognosis in PC include insulin resistance, inflammation, and hypercoagulability (36).

Physiologic insulin levels can activate the nitric oxide pathway in endothelial cells, which has beneficial antiatherogenic effects through nitric oxide–mediated vasodilation. Under insulin resistance conditions, however, the mitogenic and atherogenic pathways of insulin action signaling through the ras pathway (37) may lead to thrombosis via increased production of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and synthesis and degradation of extracellular matrix proteins (36). Previous studies have shown that obese mice had significantly higher plasma levels of coagulation factors such as PAI-1 and antithrombin III antigen, and greater factor VIII activity and combined factor II/VII/IX activity than lean mice (38). In women, a positive relationship between BMI and plasma concentrations of coagulation factors and PAI-1 has also been reported (39). Besides PAI-1 excess, other physiologic changes characterizing obesity, such as endothelial cell dysfunction and increased platelet aggregation, could also contribute to thrombosis (40).

The genome-wide association study finding that the ABO blood gene was associated with PC (41) and the phenotypic finding in a large cohort study that individuals with the non-O blood types had a higher risk of PC (42) suggest that the ABO system has an important role in human cancer. Mechanistically, ABO may contribute to PC through inflammation (41) and thrombosis (43,44). The ABO gene codes for several glycosyl transferases that add sugar residues to the H(O) antigen, thus forming the A and B antigens. These antigens reside on the surface of von Willebrand factor (VWF), a carrier protein for coagulation factor VIII. The clearance of VWF has been associated with the ABO antigen type (45). Individuals with the ABO A1 and B alleles have higher plasma levels of VWF and factor VIII (46), which confer a higher risk of thrombosis.

Few studies have addressed the relationship between obesity or ABO and thrombosis in PC. Better understanding the association between hypercoagulability and PC may provide new insights on the tumor biology and management of the disease to improve patient survival.

Metformin as a Potential Chemopreventive and Therapeutic Agent

Except avoiding cigarette smoking and maintaining a healthy lifestyle, no known method or chemopreventive agent has been demonstrated to reduce the risk of PC among individuals at higher than normal risk for the disease. Recent findings from both epidemiological investigations and experimental systems suggest that metformin, a hypoglycemic agent used in the management of diabetes, may be a potential chemopreventive agent for PC.

Two epidemiological investigations in patients with type II diabetes found that the patients taking metformin had a reduced risk of cancer. These results were significant both before and after adjusting for BMI (47,48). In the first study, metformin use among 11,876 diabetic patients, including 923 cancer cases, was associated with a 21% reduced risk for all types of malignancies, and a dose-response relationship was observed. In the second study, 2,109 of 62,809 diabetic patients developed cancer. Compared to patients treated with metformin monotherapy, those treated with sulfonylurea and insulin had 1.36- and 1.42-fold higher risks of cancer, respectively. The antidiabetic therapy–associated variation in cancer risk was not seen in patients with breast or prostate cancer but was documented in patients with colorectal cancer or PC. Our recent study in 973 patients with PC (including 259 with diabetes) and 863 controls (109 with diabetes) has shown that treatment with metformin was associated with a 62% reduction in risk of PC (49). Although the choice of antidiabetic therapy could be related to the severity of diabetes, and that could confound the association between antidiabetic therapy and risk of cancer, the validity of these observations is supported by a large amount of experimental evidence of the antitumor activity of metformin.

Metformin is a glucose-lowering drug of the biguanide class that also has a weight-reducing effect (50). Metformin decreases, rather than increases, fasting plasma insulin concentrations and acts by enhancing insulin sensitivity via activation of ′-AMP–activated protein kinase (AMPK). Apart from its important hormonal metabolic effects, metformin can inhibit proliferation and stimulate apoptosis in tumor cell lines (50) as well as in experimental animals (52). A study in a hamster model of PC showed metformin to have a significant protective effect on pancreatic tumor development induced by a chemical carcinogen and high-fat diet (53). Metformin has been shown to disrupt crosstalk between insulin and G protein–coupled receptor signaling systems through its agonistic effect on AMPK in human PC cells and to inhibit growth of human PC cells xenografted into nude mice (54). Metformin also was found to enhance immune cell (T cell) memory by altering cellular metabolism (55,56), and in patients with type II diabetes, metformin treatment was associated with biochemical evidence of improvement of endothelial function, including decreased plasma levels of VWF, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, soluble E-selectin, tissue-type plasminogen activator, PAI-1, and VEGF (57–60). Dysfunction of the vascular endothelium and elevated levels of these circulating proteins may play important roles in tumor development and progression via induction of thrombosis and angiogenesis. Interestingly, a recent retrospective study of 2,529 breast cancer patients who received chemotherapy for early stage disease found that the patients with diabetes (n=68) who received metformin had a 3 times higher pathologic complete response rate than diabetic patients not receiving metformin (n=87) (61). These experimental observations provide a strong biological rationale for investigating metformin as an antitumor and chemopreventive agent. The efficacy of metformin as an adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is being tested in clinical trials. Whether metformin or other AMPK agonists have therapeutic value in the prevention or treatment of PC should be further examined in the laboratory and in prospective clinical trials.

Summary

Obesity and diabetes play important and increasingly well-understood roles in the development and progression of PC through mechanisms mediated by insulin resistance, inflammation, and hypercoagulability. The recent genome-wide association study findings implicating the NR5A2 and ABO genes in PC support this hypothesis. Emerging from these genetic and molecular epidemiologic data is evidence that metformin and other AMPK agonists may have useful chemopreventive or therapeutic effects in PC. Further research to explore the links between genetic and molecular epidemiology and pancreatic carcinogenesis will lead to a better understanding of the etiology of PC and development of novel strategies for prevention and treatment of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by 5 P20 CA101936 SPORE in Pancreatic Cancer (Abbruzzese) and RO1 CA98380 (Li).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson K, Mack T, Silverman D. Cancer of the Pancreas. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni J, editors. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Second ed. New York: Oxford; 2006. pp. 721–762. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Body mass index and pancreatic cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1993–1998. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li D, Morris JS, Liu J, et al. Body mass index and risk, age of onset, and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:2553–2562. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everhart J, Wright D. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1995;273:1605–1609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Barzi F, Woodward M. Type-II diabetes and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2076–2083. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gapstur SM, Gann PH, Lowe W, Liu K, Colangelo L, Dyer A. Abnormal glucose metabolism and pancreatic cancer mortality. JAMA. 2000;283:2552–2558. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Graubard BI, Chari S, et al. Insulin, glucose, insulin resistance, and pancreatic cancer in male smokers. JAMA. 2005;294:2872–2878. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathur A, Zyromski NJ, Pitt HA, et al. Pancreatic steatosis promotes dissemination and lethality of pancreatic cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:989–994. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.12.026. discussion 994-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming JB, Gonzalez RJ, Petzel MQ, et al. Influence of obesity on cancer-related outcomes after pancreatectomy to treat pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 2009;144:216–221. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.House MG, Fong Y, Arnaoutakis DJ, et al. Preoperative predictors for complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: impact of BMI and body fat distribution. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:270–278. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0421-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li D, Hassan MM, Abbruzzese JL. Obesity and survival among patients with pancreatic cancer--Reply. JAMA. 2009;302:1752–1753. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andren-Sandberg A, Ihse I. Factors influencing survival after total pancreatectomy in patients with pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 1983;198:605–610. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198311000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wakasugi H, Funakoshi A, Iguchi H. Clinical observations of pancreatic diabetes caused by pancreatic carcinoma, and survival period. Int J Clin Oncol. 2001;6:50–54. doi: 10.1007/pl00012080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson LC, Pollack LA. Therapy insight: influence of type 2 diabetes on the development, treatment and outcomes of cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:48–53. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganti AK, Potti A, Koch M, et al. Predictive value of clinical features at initial presentation in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a series of 308 cases. Med Oncol. 2002;19:233–237. doi: 10.1385/MO:19:4:233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Marmot M, Smith GD. Diabetes status and post-load plasma glucose concentration in relation to site-specific cancer mortality: findings from the original Whitehall study. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:873–881. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1050-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barone BB, Yeh HC, Snyder CF, et al. Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2754–2764. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zyromski NJ, Mathur A, Pitt HA, et al. Obesity potentiates the growth and dissemination of pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2009;146:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asano T, Yao Y, Shin S, McCubrey J, Abbruzzese JL, Reddy SA. Insulin receptor substrate is a mediator of phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation in quiescent pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9164–9168. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueda S, Hatsuse K, Tsuda H, et al. Potential crosstalk between insulin-like growth factor receptor type 1 and epidermal growth factor receptor in progression and metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:788–796. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauer TW, Somcio RJ, Fan F, et al. Regulatory role of c-Met in insulin-like growth factor-I receptor-mediated migration and invasion of human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1676–1682. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Javle MM, Varadhachary GR, Shroff RT, et al. Phase I/II study of MK-0646, the humanized monoclonal IGF-1R antibody in combination with gemcitabine or gemcitabine plus erlotinib for advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:7s. (suppl; abstr 4039). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen GM, Amundadottir L, Fuchs CS, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies pancreatic cancer susceptibility loci on chromosomes 13q22.1, 1q32.1 and 5p15.33. Nat Genet. 2010;24:224–228. doi: 10.1038/ng.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee YK, Moore DD. Liver receptor homolog-1, an emerging metabolic modulator. Front Biosci. 2008;13:5950–5958. doi: 10.2741/3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Botrugno OA, Fayard E, Annicotte JS, et al. Synergy between LRH-1 and beta-catenin induces G1 cyclin-mediated cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2004;15:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Annicotte JS, Fayard E, Swift GH, et al. Pancreatic-duodenal homeobox 1 regulates expression of liver receptor homolog 1 during pancreas development. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6713–6724. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6713-6724.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubois MJ, Bergeron S, Kim HJ, et al. The SHP-1 protein tyrosine phosphatase negatively modulates glucose homeostasis. Nat Med. 2006;12:549–556. doi: 10.1038/nm1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwaki M, Matsuda M, Maeda N, et al. Induction of adiponectin, a fat-derived antidiabetic and antiatherogenic factor, by nuclear receptors. Diabetes. 2003;52:1655–1663. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barb D, Williams CJ, Neuwirth AK, Mantzoros CS. Adiponectin in relation to malignancies: a review of existing basic research and clinical evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:s858–s866. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.858S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Weinstein S, Pollak M, et al. Prediagnostic adiponectin concentrations and pancreatic cancer risk in male smokers. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1047–1055. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fox CS, Heard-Costa N, Cupples LA, Dupuis J, Vasan RS, Atwood LD. Genome-wide association to body mass index and waist circumference: the Framingham Heart Study 100K project. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8 Suppl 1:S18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khorana AA, Fine RL. Pancreatic cancer and thromboembolic disease. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:655–663. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01606-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakchbandi IA, Lohr JM. Coagulation, anticoagulation and pancreatic carcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:445–455. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darvall KA, Sam RC, Silverman SH, Bradbury AW, Adam DJ. Obesity and thrombosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skolnik EY, Batzer A, Li N, et al. The function of GRB2 in linking the insulin receptor to Ras signaling pathways. Science. 1993;260:1953–1955. doi: 10.1126/science.8316835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lijnen HR. Role of fibrinolysis in obesity and thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2009;123 Suppl 4:S46–S49. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(09)70143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He G, Pedersen SB, Bruun JM, Lihn AS, Jensen PF, Richelsen B. Differences in plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 in subcutaneous versus omental adipose tissue in non-obese and obese subjects. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35:178–182. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nieuwdorp M, Stroes ES, Meijers JC, Buller H. Hypercoagulability in the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amundadottir L, Kraft P, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the ABO locus associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41:986–990. doi: 10.1038/ng.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolpin BM, Chan AT, Hartge P, et al. ABO blood group and the risk of pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:424–431. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiggins KL, Smith NL, Glazer NL, et al. ABO genotype and risk of thrombotic events and hemorrhagic stroke. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maisonneuve P, Iodice S, Lohr JM, Lowenfels AB. Re: ABO blood group and the risk of pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1156–1157. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schleef M, Strobel E, Dick A, et al. Relationship between ABO and secretor genotype with plasma levels of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor in thrombosis patients and control individuals. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:100–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jenkins PV, O'Donnell JS, Jenkins PV, O'Donnell JS. ABO blood group determines plasma von Willebrand factor levels: a biologic function after all? Transfusion. 2006;46:1836–1844. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM, Alessi DR, Morris AD. Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. BMJ. 2005;330(7503):1304–1305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38415.708634.F7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Currie CJ, Poole CD, Gale EAM. The influence of glucose-lowering therapies on cancer risk in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1766–1777. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li D, Yeung SC, Hassan MM, et al. Antidiabetic therapies affect risk of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:482–488. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers JR. Metformin: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:25–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-1-200207020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alimova IN, Liu B, Fan Z, et al. Metformin inhibits breast cancer cell growth, colony formation and induces cell cycle arrest in vitro. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:909–915. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.6.7933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anisimov VN, Berstein LM, Egormin PA, et al. Effect of metformin on life span and on the development of spontaneous mammary tumors in HER-2/neu transgenic mice. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:685–693. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneider MB, Matsuzaki H, Haorah J, et al. Prevention of pancreatic cancer induction in hamsters by metformin. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(5):1263–1270. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kisfalvi K, Eibl G, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. Metformin disrupts crosstalk between G protein-coupled receptor and insulin receptor signaling systems and inhibits pancreatic cancer growth. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6539–6545. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pearce EL, Walsh MC, Cejas PJ, et al. Enhancing CD8 T-cell memory by modulating fatty acid metabolism. Nature. 2009;460:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prlic M, Bevan MJ. Immunology: a metabolic switch to memory. Nature. 2009;460:41–42. doi: 10.1038/460041a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ersoy C, Kiyici S, Budak F, et al. The effect of metformin treatment on VEGF and PAI-1 levels in obese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;81:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Jager J, Kooy A, Lehert P, et al. Effects of short-term treatment with metformin on markers of endothelial function and inflammatory activity in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Intern Med. 2005;257:100–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isoda K, Young JL, Zirlik A, et al. Metformin inhibits proinflammatory responses and nuclear factor-kappaB in human vascular wall cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:611–617. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000201938.78044.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mather KJ, Verma S, Anderson TJ. Improved endothelial function with metformin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1344–1350. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiralerspong S, Palla SL, Giordano SH, et al. Metformin and pathologic complete responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in diabetic patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3297–3302. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.19.6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]