Abstract

Bovine serum albumin (BSA) in D2O at 25 °C and pD 7.0 was found to catalyze the deuterium exchange reactions of [1-13C]-glycolaldehyde ([1-13C]-GA) to form [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA. The formation of [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA in a total yield of 51 ± 3% was observed at early reaction times, and at latter times [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA was observed to undergo BSA-catalyzed conversion to [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA. The overall second-order rate constant for these deuterium exchange reactions is (kE)P = 0.25 M−1 s−1. By comparison, values of (kE)P = 0.04 M−1 s−1 (Go, M. K., Amyes, T. L., and Richard, J. P. (2009), Biochemistry 48, 5769–5778) and 0.06 M−1 s−1 (Go, M. K., Koudelka, A., Amyes, T. L., and Richard, J. P. (2010), Biochemistry 49, 5377–5389) have been determined, respectively, for the wildtype- and K12G mutant TIM-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions of [1-13C]-GA to form [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA. These data show that TIM and BSA exhibit a modest catalytic activity towards deprotonation of α-hydroxy α-carbonyl carbon. It is suggested that this activity is intrinsic to many globular proteins, and that it must be enhanced to demonstrate successful de novo design of protein catalysts of reactions through enamine intermediates.

Keywords: Catalysis, Proton-Transfer, Enolate, Protein-Catalyzed, Maillard Reaction

The rate-acceleration calculated for an enzymatic reaction depends upon the choice of the rate constant for the reference nonenzymatic reaction, and upon whether this rate constant is compared with kcat (s−1) or kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) for the enzymatic reaction. For example, the ratio of the first-order rate constant kcat = 430 s−1 for chicken muscle triosephosphate isomerase-catalyzed (TIM)1 isomerization of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) at pH 7.0 and 30° C (1) and 2.1 × 10−7 s−1 for the solvent-catalyzed reaction at the same temperature and pH gives a rate acceleration of ca 109-fold (2). On the other hand, a comparison of second-order rate constants kcat/Km for isomerization of DHAP catalyzed by TIM and kB for isomerization catalyzed by the tertiary amine quinuclidinone gives a rate acceleration of ≈1010-fold (3). This is the approximate effect of the protein catalyst on the activation barrier for deprotonation of DHAP by a small general base in water, which is similar to the carboxylate anion side chain of Glu-165 that deprotonates enzyme-bound DHAP (4–6).

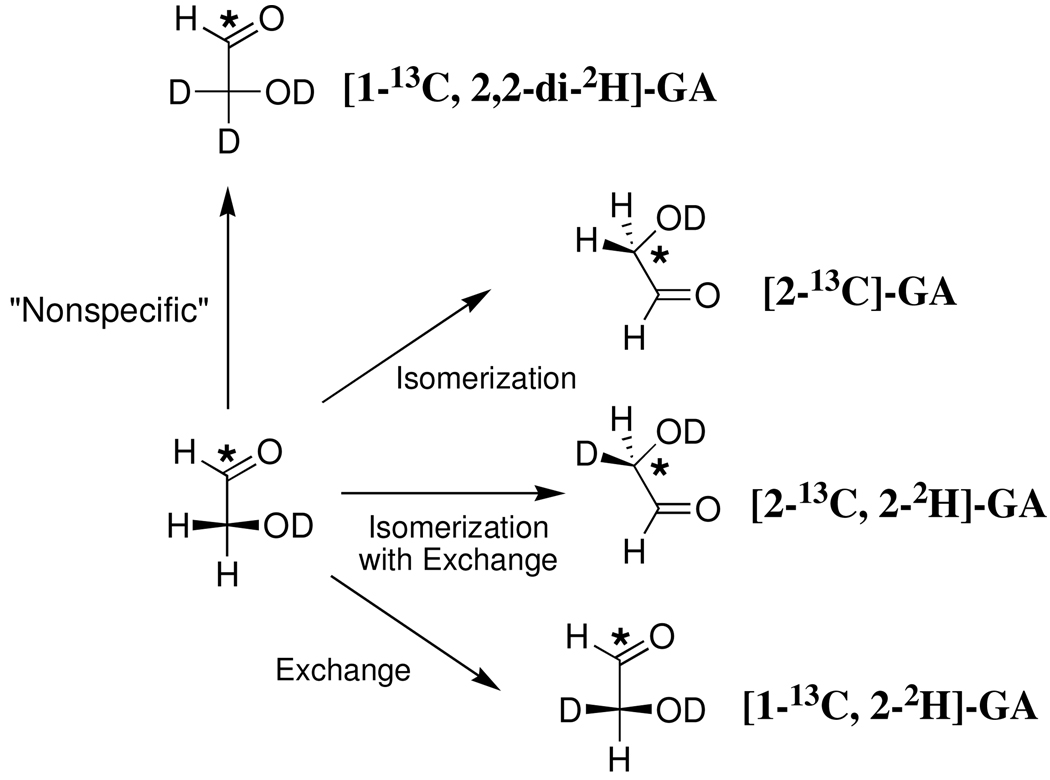

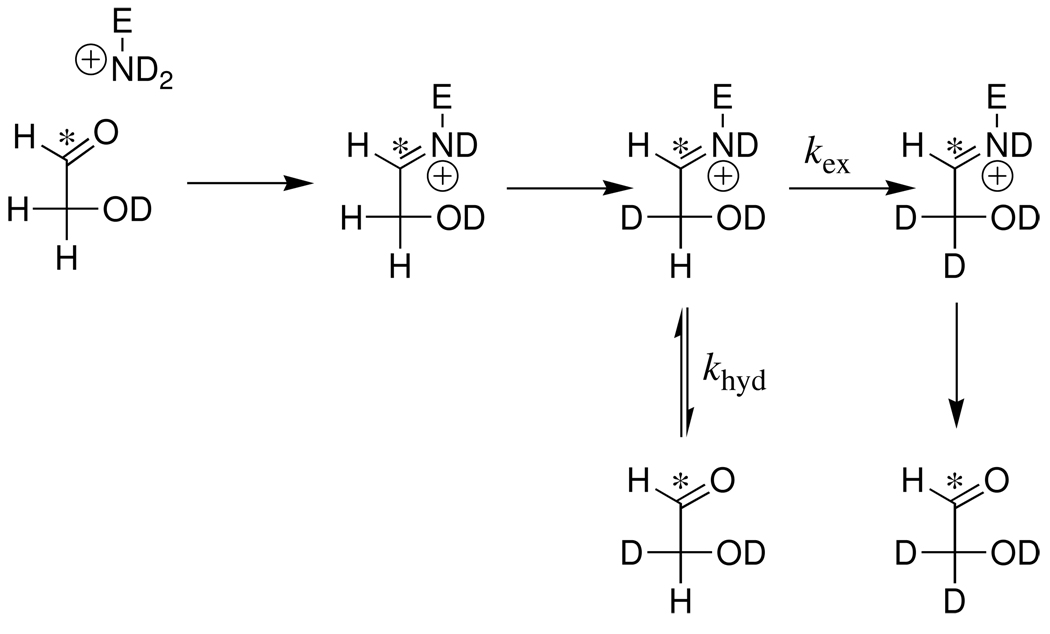

The rate acceleration for an enzymatic reaction might also be calculated as the ratio of the second-order rate constants for the specific enzymatic and the nonspecific protein-catalyzed reactions, when nonspecific protein catalysis is observed (7–11). This provides a measure of the apparent effect on protein reactivity of evolution or de novo design of a specific catalytic active site. We have reported a second-order rate constant of kcat/Km = 0.19 M−1 s−1 for the TIM-catalyzed reactions of [1-13C]-glycolaldehyde ([1-13C]-GA] to form [2-13C]-GA, [2-13C, 2-2H]- GA, [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA from reaction at the enzyme active site, and [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA from a nonspecific protein-catalyzed reaction (Scheme 1) (12). The K12G mutation of yeast TIM causes a ca 105-fold decrease in kcat/Km for isomerization of the physiological substrate D-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GAP), but only a two-fold decrease in the apparent kcat/Km for the reaction of [1-13C]-GA to 0.1 M−1 s−1. No isomerization products [2-13C]-GA or [2-13C, 2-2H]-GA were observed from the K12G mutant TIM-catalyzed reaction of [1-13C]-GA in D2O: the major reaction product is [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA (13) from a nonspecific reaction. This and other evidence shows that a functioning enzyme active site is not required for the TIM-catalyzed deuterium exchange reaction of [1-13C]-GA (13). The results suggest that other proteins may show a modest catalytic activity towards deprotonation of α-hydroxy α-carbonyl carbon.

Scheme 1.

Serum albumins are abundant plasma proteins that bind a wide variety of hydrophobic molecules, and which catalyze several chemical reactions of small molecules (7–9, 11). We report here an apparent second-order rate constant of kE = 0.25 M−1 s−1 for bovine serum albumin-catalyzed (BSA) reaction of [1-13C]-GA to form [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA, which is similar to the value determined for the reactions catalyzed by wildtype and K12G mutant TIM under the same conditions. We suggest that the real challenge to the design of enzymes that catalyze deprotonation of α-carbonyl carbon is to obtain rate constants significantly greater than the value of kE = 0.25 M−1 s−1 for the BSA-catalyzed reaction of [1-13C]-GA.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Bovine serum albumin was from Roche. Glycolaldehyde (99% enriched with 13C at C-1 was from Omicron Biochemicals. Deuterium oxide (99.9% D) and deuterium chloride (35% w/w, 99.9% D) were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. Water was obtained from a Milli-Q Academic purification system. Imidazole was recrystallized from benzene. All other commercially available chemicals were reagent grade or better and were used without further purification.

[1-13C]-GA (1 mL of a 90 mM solution in H2O) was reduced to a volume of ca. 100 µL by rotary evaporation, 5 mL of D2O was added, and the volume was again reduced to ca. 100 µL by rotary evaporation. This procedure was repeated twice more and 900 µL of D2O was added to the final solution to give a volume of 1 mL. The stock solution of [1-13C]-GA in D2O was stored at room temperature to minimize the content of the glycolaldehyde dimer (14). The concentration of [1-13C]-GA in the stock solution was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy, as described in earlier work (12, 14).

1H NMR Analyses

1H NMR spectra at 500 MHz were recorded in D2O at 25 °C using a Varian Unity Inova 500 spectrometer that was shimmed to give a line width of ≤ 0.5 Hz for the downfield peaks of the double triplet due to the C-1 proton of [1-13C]-GA hydrate. Spectra (16 – 64 transients) were obtained using a sweep width of 6000 Hz, a pulse angle of 90° and an acquisition time of 4 – 6 s, with zero-filling of the data to 128 K. To ensure accurate integrals for the protons of interest, a relaxation delay between pulses of 120 s (> 8T1) was used. Baselines were subjected to a first-order drift correction before determination of integrated peak areas. Chemical shifts are reported relative to a value of 4.67 ppm for HOD at pD 7.0.

BSA-Catalyzed Reaction

The concentration of BSA was calculated using a value of 44,000 M−1 cm−1 for its molar extinction coefficient (15). BSA [ca 70 mg/mL] was dissolved in 30 mM imidazole (20% free base) at pD 7.0, I = 0.1 (NaCl) and the solution was dialyzed at 4 °C against 30 mM imidazole buffer (20% free base, pD 7.0) in D2O at I = 0.1 (NaCl). The BSA-catalyzed reaction of [1-13C]-GA in D2O was initiated by adding 0.18 mL of BSA (ca. 42 mg/mL) in 30 mM imidazole buffer (20% free base, pD 7.0) at I = 0.1 (NaCl) in D2O to 0.57 mL of a buffered solution of [1-13C]-GA in D2O to give final concentrations of 20 mM [1-13C]-GA, 20 mM imidazole and 0.15 mM BSA at pD 7.0 and I = 0.1 (NaCl). This solution was transferred to an NMR tube, and the 1H NMR spectrum at 25 °C was recorded immediately (32 transients). 1H NMR spectra were then recorded periodically over a period of 120 h. The fraction of the remaining substrate [1-13C]-GA (fS) and the fraction of [1-13C]-GA converted to the identifiable products [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H2]-GA (fP) were determined from the integrated areas of the relevant 1H NMR signals, and using the signal due to the C-(4,5) protons of imidazole as an internal standard, as described in previous work (14, 16, 17).

The observed first-order rate constant, kobsd, for the disappearance of [1-13C]-GA was determined as the slope of the linear semi-logarithmic plot of reaction progress against time (eq 1). The second-order rate constant for the BSA-catalyzed reactions of [1-13C]-GA was calculated using eq 2, where fcar = 0.061 is the fraction of GA present in the reactive carbonyl form (14) and [E] = 1.5 × 10−4 M is the concentration of BSA.

| (1) |

| (2) |

RESULTS

The disappearance of the C-2 hydrogen of [1-13C]-GA hydrate in D2O at pD 7.0 (20 mM imidazole) and 25 °C in the presence of 1.5 × 10−4 M bovine serum albumin (BSA) was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy for 120 h, at which time only 14% of fully hydrogen-labeled [1-13C]-GA remained. The time course for this reaction (not shown) showed a good fit to a linear correlation (eq 1) with a slope of kobsd = 4.5 × 10−6 s−1. The second-order rate constant for the BSA-catalyzed reactions, calculated from eq 2, is (kE)obsd = 0.49 ± 0.02 M−1s−1.

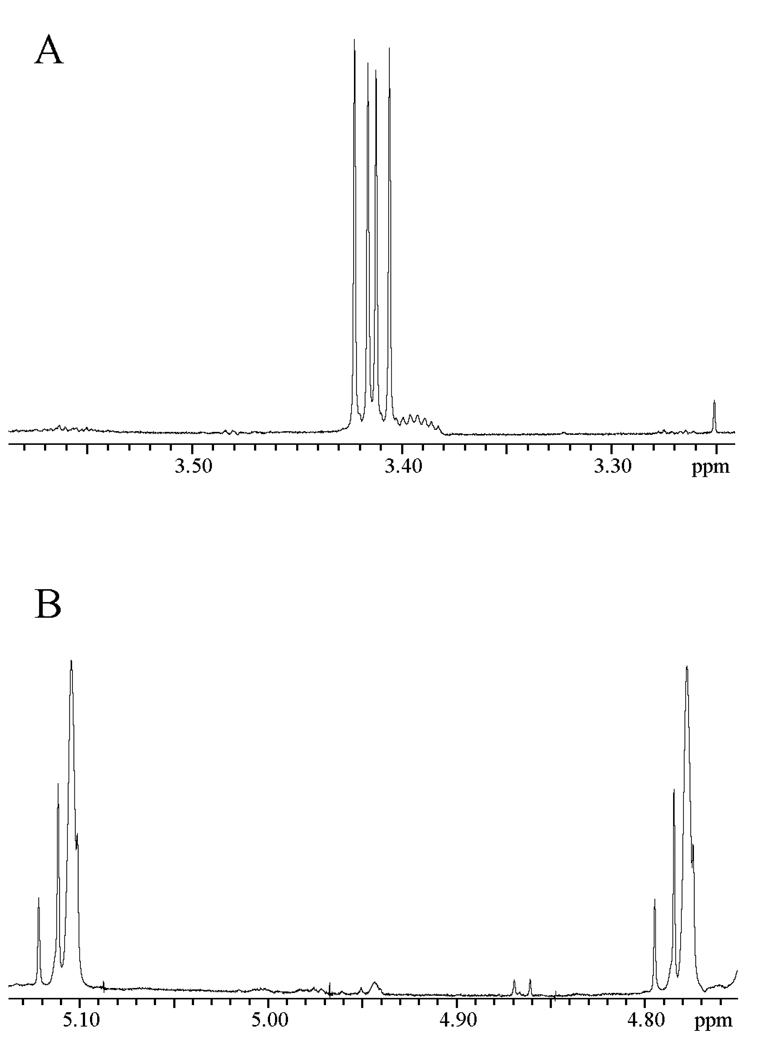

Figure 1 shows portions of the 1H NMR spectrum at 500 MHz of the reaction mixture obtained after the 120 h reaction of [1-13C]-GA (20 mM) in the presence of 0.15 mM BSA in D2O at pD 7.0 and 25 °C. Under our reaction conditions GA exists as 93.9% in the hydrated form and 6.1% in the free carbonyl form (14, 18). The following chemical shifts refer to the hydrates of the isotopomers shown in Chart 1.

Figure 1.

Portions of the 1H NMR spectrum at 500 MHz of the reaction mixture obtained from the reaction of [1-13C]-GA (20 mM) for 120 h in the presence of 0.15 mM BSA in D2O at pD 7.0, 25 °C and I = 0.10 (NaCl). A - The spectrum in the region of the C-2 hydron(s) of the isotopomers of GA hydrate; B - The spectrum in the region of the C-1 hydron of the isotopomers of GA hydrate.

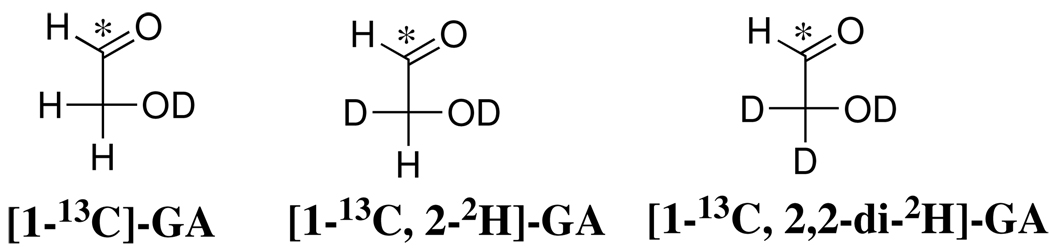

Chart 1.

The signals due to the C-2 protons of [1-13C]-GA appear as a double doublet at 3.410 ppm (2JHC = 3 Hz, 3JHH = 5 Hz) (Figure 1A) (12). The TIM-catalyzed incorporation of deuterium into [1-13C]-GA to give [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA results in an upfield shift of 0.021 ppm for the signal for the remaining C-2 proton of this compound, due to the perturbation of the chemical shift by the α-deuterium (19–21). The signal for the C-2 proton of [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA appears as a multiplet on the upfield edge of the signal for the C-2 protons of [1-13C]-GA (Figure 1A). This is a poorly resolved double double triplet, as a result of a three-bond HH coupling (J = 5 Hz), a two-bond HC coupling (J = 3 Hz) and a two-bond HD coupling (J ≈ 2 Hz) (12). The signal due to the C-1 proton of [1-13C]-GA appears as a double triplet at 4.945 ppm (1JHC = 163 Hz, 3JHH = 5 Hz) (Figure 1B) (12). The signal due to the C-1 proton of [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA appears as a broad doublet (1JHC = 163 Hz) at 4.930 ppm that is shifted 0.015 ppm upfield from the double triplet due to the C-1 proton of [1-13C]-GA as a result of the two β-deuteriums (Figure 1B) (12). The signal for the C-1 proton of [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA appears as a broad double doublet at 4.940 ppm, shifted 0.005 ppm upfield of the double triplet due to the C-1 proton of [1-13C]-GA as a result of the single β-deuterium (12). However, this signal is not resolved from the signals for the C-1 protons of [1-13C]-GA and [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA.

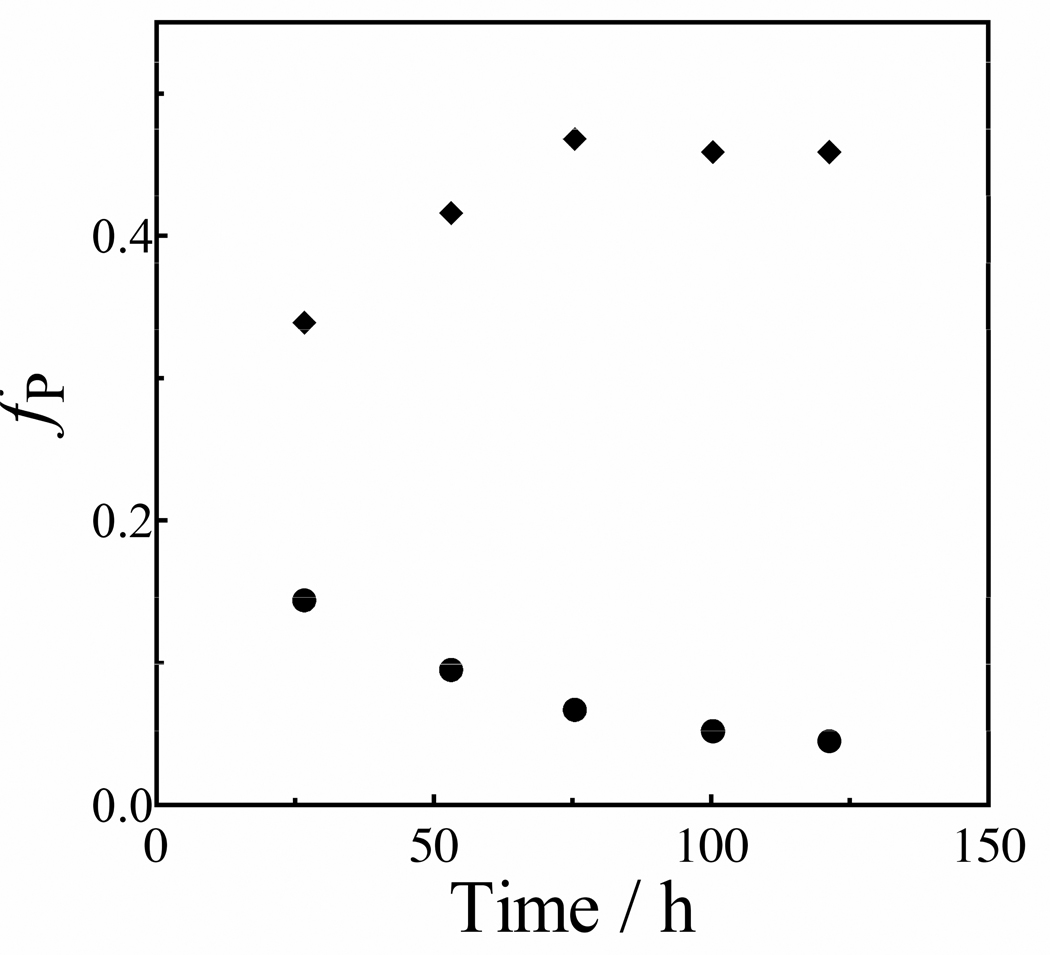

The fraction of [1-13C]-GA converted to [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H2]-GA (fP) was determined from the integrated areas of the relevant 1H NMR signals, as described in earlier work (12). Figure 2 shows the change, with time, in the yields of the products [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2,2-2H]-GA of the BSA-catalyzed reactions of [1-13C]-GA. The average of the total yields of the products of deuterium exchange reactions of [1-13C]-GA determined at five different reaction times, 51 ± 3%, is similar to the 56 ± 5% product yield determined for the reaction of [1-13C]-GA catalyzed by K12G mutant TIM (13). However, the mutant enzyme-catalyzed reaction gave only the dideuterium labeled product [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H2]-GA. No attempt was made to identify the other pathways for the reactions [1-13C]-GA in the presence of BSA.

Figure 2.

Time course for the formation of products of the reaction of [1-13C]-GA (20 mM) in the presence of 0.15 mM BSA in D2O at pD 7.0, 25 °C and I = 0.10 (NaCl), where fP is the fractional yield of the product at the given reaction time. Key: (◆), fractional yield of [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA; (●), fractional yield of [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA.

DISCUSSION

The loss of the signal for the C-2 hydrogen of [1-13C]-GA in D2O at pD 7.0 (20 mM imidazole) and 25 °C in the presence of 1.5 × 10−4 M BSA was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. The reaction is first-order with a rate constant of kobsd = 4.5 × 10−6 s−1 and an apparent second-order rate constant of (kE) = 0.49 ± 0.02 M−1 s−1 for the protein-catalyzed reaction (eq 2). The two major products of the BSA-catalyzed deuterium exchange reaction of [1-13C]-GA are [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA (Figure 2): the total yield of these products is fp = 0.51 ± 0.03 and the second-order rate constant for the protein-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions is (kE)P = (0.49 M−1 s−1)(0.51) = 0.25 M−1 s−1 (Table 1). Both [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA are observed as products at early reaction times, but at later times [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA is converted to [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Kinetic Parameters for Protein-Catalyzed Reactions of [1-13C]-GA in D2O to form [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA at 25 °C and pD 7.0.

| Catalyst | (kE)obsd (M−1 s−1) a |

fPb | (kE)P (M−1 s−1) c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wildtype Chicken TIM d |

0.19 | ≈ 0.2 | ≈ 0.04 |

| K12G Chicken TIM e |

0.11 ± 0.005 | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 0.06 ± 0.006 |

| BSA f | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 0.25 ± 0.02 |

|

0.0065 M−1 s−1 g | ||

The observed second-order rate constant for the protein-catalyzed reactions of [1-13C]-GA. The second-order rate constants for catalysis by TIM are calculated for one monomer of this dimeric enzyme. The quoted errors are the standard deviation of linear correlations of reaction progress against time.

The fractional yield of the products from the protein-catalyzed reactions of [1-13C]-GA. This is the average of the product yields determined at 3–5 different reaction times.

The second-order rate constant for the protein-catalyzed deuterium exchange reactions of [1-13C]-GA: (kE)P = fP(kE)obs.

Data from reference (12)

Data from reference (13).

This work.

The second-order rate constant for general base-catalyzed deprotonation of glyceraldehyde by 3-quinuclidinone (22).

The 37-fold larger second-order rate constant (kE)P = 0.25 M−1 s−1 for the BSA-catalyzed deuterium exchange reaction of [1-13C]-GA compared with kB = 0.0065 M−1 s−1 for 3-quinuclidinone-catalyzed deprotonation of glyceraldehyde (Table 1) (22) shows that the protein catalyst provides a modest activation of α-hydroxy α-carbonyl carbon towards deprotonation. The simplest reaction mechanism would proceed with direct deprotonation of [1-13C]-GA by a basic side chain of BSA (23). However, the observation that dideuterium-labeled product [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA appears with no discernible lag at early reaction times (Figure 2) shows that monodeuterium-labeled 1-13C, 2-2H]-GA must remain bound to BSA for a time sufficient to allow for a second deuterium exchange reaction. This observation is difficult to reconcile with a simple noncovalent Michaelis complex, because the complex between BSA and the small two carbon substrate GA is expected to be weak and undergo fast dissociation.

We suggest that the BSA-catalyzed deuterium exchange reaction proceeds through a covalent Schiff base intermediate (Scheme 2). The substrate first forms a Schiff base to a lysine side chain, which undergoes deuterium exchange through an enamine intermediate, presumably promoted by a second basic side chain. The initially formed monodeuterium-labeled Schiff base then undergoes base-catalyzed deuterium exchange to form [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA at a rate that is competitive with hydrolysis of the Schiff base that releases [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA from the protein (kex ≈ khyd, Scheme 2). The hydrogen exchange reaction of perdeuterated acetone-d6 in H2O, catalyzed by diamines, proceeds directly to form acetone labeled with multiple -H (24, 25). This observation shows that rate of intramolecular deprotonation of the acetone imine by a second tethered amine is competitive with the rate of hydrolysis of the imine to release deuterium labeled product. It provides a nonenzymatic precedent for Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

The reaction of reducing sugars with protein lysine amino groups is one example of the Maillard reaction, which proceed by complex pathways that are difficult to characterize and give a large number of reactions products (26). It has been shown in a broader study of Maillard reactions that the 170 h reaction between 20 mM GA and 100 µM BSA labels only 3% of total lysine as the Nε–carboxymethyl adduct (27) by an unknown reaction mechanism. The observation of only a small change (≈ 3%, vide infra) in the concentration of the free amino groups of the lysine side chains (27) shows that nearly all of the lysine side-chains remain in the reactive amino form during our 120 h reaction of BSA with 20 mM [1-13C]-GA.

BSA and TIM-Catalyzed Reactions of [1-13C]-GA

The observed second-order rate constant for wildtype chicken TIM-catalyzed reactions of [1-13C]-GA is (kE)obsd = 0.19 M−1 s−1 (12). The yield of [2-13C]-GA, [2-13C, 2-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA (Scheme 1) from the isomerization and exchange reactions of [1-13C]-GA at the functional enzyme active site is ca 50%, the yield of [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA from the dideuterium exchange reaction is ca 20%, and ca 30% of the reaction products could not be identified. These data give (kE)P = (0.2)(0.19 M−1 s−1) ≈ 0.04 M−1s−1 (Table 1) as the second-order rate constant for the protein-catalyzed reaction of [1-13C]-GA to form [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA (Table 1).

The observed second-order rate constant for the K12G yeast TIM-catalyzed reactions of [1-13C]-GA is (kE)obsd = 0.11 M−1 s−1 (13). This mutation eliminates the products of the specific isomerization and deuterium exchange reactions of [1-13C]-GA at the enzyme active site (Scheme 1) (13). The yield of [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA from the protein-catalyzed deuterium exchange reaction therefore increases from ca 20% for wildtype TIM to 56 ± 5% for K12G mutant TIM. This shows that a functioning enzyme active site is not required to observe protein-catalyzed reaction of [1-13C]-GA to form [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA. The second-order rate constant for the K12G TIM-catalyzed reaction of [1-13C]-GA to form [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA, (kE)P = (0.56)(0.11 M−1 s−1) = 0.06 M−1s−1, is similar to (kE)P ≈ 0.04 M−1 s−1 determined for the reaction catalyzed by wildtype TIM (Table 1).

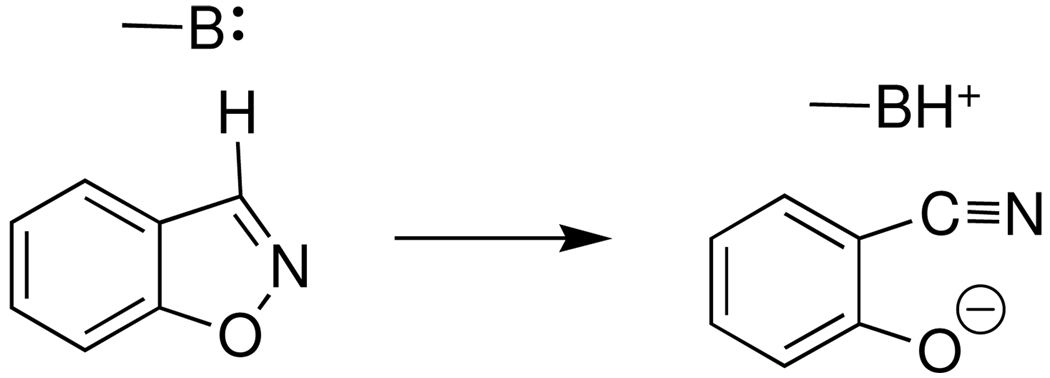

By comparison, the second-order rate constant of (kE)P = 0.25 M−1 s−1 for the BSA-catalyzed deuterium exchange reaction of [1-13C]-GA in D2O to form [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA and [1-13C, 2,2-di-2H]-GA is (4–6)-fold larger than the rate constants for the reactions catalyzed by wildtype and K12G mutant TIM (Table 1). The larger rate constant may be due to the larger number of total lysines residues at BSA (60 residues) compared to a chicken TIM monomer (22 residues). We note, however, that nothing is known about the reactivity of these individual amino side chains and that it is possible that deuterium exchange is due to the reaction of one or a few "activated" lysine acid side chains at TIM and/or BSA. In this regard, there is good evidence that the BSA-catalyzed rearrangement of 5-nitrobenzyisoxazole to 4-nitrosalicylonitrile (Scheme 3) is initiated by deprotonation of the substrate by the basic side-chain of a single Lys-220 (9). The high apparent reactivity of this lysine was proposed to be due to its placement at a hydrophobic pocket (28), which was assumed to bind the substrate with Kd ≈ Km = 0.72 mM (9).

Scheme 3.

There is a larger initial yield of the monodeuteriated product [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA from the BSA-catalyzed reaction of [1-13C]-GA in D2O (ca 20%, Figure 2) compared with the nonspecific TIM-catalyzed reactions (no [1-13C, 2-2H]-GA detected) (12, 13). This shows that the iminium ion intermediate(s) of the BSA-catalyzed reactions undergo deuterium exchange (kex, Scheme 2) and hydrolysis (khyd) with similar rate constants, but that (kex ≫ khyd) for the reaction of the iminium ion intermediate of the nonspecific reactions of TIM with [1-13C]-GA.

Concluding remarks

BSA-catalyzes not only the reactions of substrates that bind to a hydrophobic site at the protein (Scheme 3) (9–11), but also deprotonation of the small and relatively hydrophilic substrate GA. We have not investigated the origin of the catalytic power of BSA towards deprotonation of [1-13C]-GA, but note that it was shown in earlier studies on small molecule catalysts that diamines act as bifunctional catalysts of hydron exchange and that formation of the iminium ion adduct results in multiple intramolecular amine-catalyzed hydron exchange reactions through an enamine intermediate, at a rate that is faster than hydrolysis of the iminium ion to regenerate the ketone and diamine (24, 29). We suggest, similarly, that these protein-catalyzed reactions are due to the action of amino side chain of lysine and a second neighboring basic amino acid side chain.

Protein designers sometimes claim success when they observe so-called large rate accelerations for their designed catalysts, but these claims ignore the relatively large intrinsic catalytic activities sometimes observed for globular proteins. We note here that the second-order rate constant (kE)P = 0.25 M−1 s−1 for the BSA-catalyzed deuterium exchange reaction of [1-13C]-GA is similar to second-order rate constants reported for catalysis of retroaldol cleavage reactions by small peptides (30) and by a computationally designed protein catalyst (31, 32) through enamine reaction intermediates. We suggest that the relatively high intrinsic catalytic activity of proteins towards deprotonation of [1-13C]-GA should serve as the reference point in calculating the rate acceleration for computationally designed catalysts of reactions of α-carbonyl carbon through enamine reaction intermediates. It would therefore be useful to include with reports of de novo design of new catalytic activities, a control experiment to compare the kinetic parameters for the designed protein catalyst with the parameters for the jack-of-all-trades protein catalyst BSA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant GM39754 from the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Abbreviations: TIM, triosephosphate isomerase; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; GAP, (R)-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; GA, glycolaldehyde; BSA, bovine serum albumin; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance.

References

- 1.Plaut B, Knowles JR. pH-Dependence of the triose phosphate isomerase reaction. Biochem. J. 1972;129:311–320. doi: 10.1042/bj1290311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall A, Knowles JR. The uncatalyzed rates of enolization of dihydroxyacetone phoshate and of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate in neutral aqueous solution. The quantitative assessment of the effectiveness of an enzyme catalyst. Biochemistry. 1975;14:4348–4353. doi: 10.1021/bi00690a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richard JP. Acid-base catalysis of the elimination and isomerization reactions of triose phosphates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:4926–4936. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartman FC. Haloacetol phosphates. Characterization of the active site of rabbit muscle triose phosphate isomerase. Biochemistry. 1971;10:146–154. doi: 10.1021/bi00777a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De la Mare S, Coulson AFW, Knowles JR, Priddle JD, Offord RE. Active-site labeling of triose phosphate isomerase. Reaction of bromohydroxyacetone phosphate with a unique glutamic acid residue and the migration of the label to tyrosine. Biochem. J. 1972;129:321–331. doi: 10.1042/bj1290321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raines RT, Sutton EL, Straus DR, Gilbert W, Knowles JR. Reaction energetics of a mutant triose phosphate isomerase in which the active-site glutamate has been changed to aspartate. Biochemistry. 1986;25:7142–7154. doi: 10.1021/bi00370a057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu Y, Houk KN, Kikuchi K, Hotta K, Hilvert D. Nonspecific medium effects versus specific group positioning in the antibody and albumin catalysis of the base-promoted ring-opening reactions of benzisoxazoles. J. Am. Chem Soc. 2004;126:8197–8205. doi: 10.1021/ja0490727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollfelder F, Kirby AJ, Tawfik DS, Kikuchi K, Hilvert D. Characterization of proton-transfer catalysis by serum albumins. J. Am. Chem Soc. 2000;122:1022–1029. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kikuchi K, Thorn SN, Hilvert D. Albumin-catalyzed proton transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8184–8185. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh S-WM, Means GE. Characterization of a small apolar anion binding site of human serum albumin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1979;192:73–79. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Means GE, Bender ML. Acetylation of human serum albumin by p-nitrophenyl acetate. Biochemistry. 1975;14:4989–4994. doi: 10.1021/bi00693a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Go MK, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Hydron transfer catalyzed by triosephosphate isomerase. Products of the direct and phosphite-activated isomerization of [1-13C]-glycolaldehyde in D2O. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5769–5778. doi: 10.1021/bi900636c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Go MK, Koudelka A, Amyes TL, Richard JP. The role of Lys-12 in catalysis by triosephosphate isomerase: A two-part substrate approach. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5377–5389. doi: 10.1021/bi100538b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amyes TL, Richard JP. Enzymatic catalysis of proton transfer at carbon: activation of triosephosphate isomerase by phosphite dianion. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5841–5854. doi: 10.1021/bi700409b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorbtion coefficient of a protein. Protein Science. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Donoghue AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Hydron transfer catalyzed by triosephosphate isomerase. Products of isomerization of (R)-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate in D2O. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2610–2621. doi: 10.1021/bi047954c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Donoghue AC, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Hydron transfer catalyzed by triosephosphate isomerase. Products of isomerization of dihydroxyacetone phosphate in D2O. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2622–2631. doi: 10.1021/bi047953k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins GCS, George WO. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of glycolaldehyde. J. Chem. Soc. (B) 1971:1352–1355. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amyes TL, Richard JP. Generation and stability of a simple thiol ester enolate in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10297–10302. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amyes TL, Richard JP. Determination of the pKa of ethyl acetate: Bronsted correlation for deprotonation of a simple oxygen ester in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:3129–3141. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard JP, Williams G, O'Donoghue AC, Amyes TL. Formation and stability of enolates of acetamide and acetate anion: An Eigen plot for proton transfer at α-carbonyl carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:2957–2968. doi: 10.1021/ja0125321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amyes TL, O'Donoghue AC, Richard JP. Contribution of phosphate intrinsic binding energy to the enzymatic rate acceleration for triosephosphate isomerase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11325–11326. doi: 10.1021/ja016754a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richard JP, Amyes TL. Proton transfer at carbon. Cur. Op. Chem. Biol. 2001;5:626–633. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(01)00258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hine J. Bifunctional catalysis of α-hydrogen exchange of aldehydes and ketones. Acc. Chem. Res. 1978;11:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hine J, Li W. Catalysis of α-hydrogen exchange. XIX. Bifunctional catalysis of the dedeuteration of acetone-d6 by conformationally constrained derivatives of N,N-dimethyl-1,3-propanediamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:3287–3294. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ledl F, Ledl E. New aspects of the Maillard reaction in food and the human body. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1990;29:565–594. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glomb MA, Monnier VM. Mechanism of protein modification by glyoxal and glycolaldehyde, reactive intermediates of the Maillard reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:10017–10026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He XM, Carter DC. Atomic structure and chemistry of human serum albumin. Nature. 1992;358:209–215. doi: 10.1038/358209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hine J, Li W. Catalysis of α-hydrogen exchange. XIX. Bifunctional catalysis of the dedeuteration of acetone-d6 by conformationally constrained derivatives of N,N-dimethyl-1,3-propanediamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:3287–3294. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka F, Fuller R, Barbas CF. Development of small designer aldolase enzymes: Catalytic activity, folding, and substrate specificity. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7583–7592. doi: 10.1021/bi050216j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lassila JK, Baker D, Herschlag D. Origins of catalysis by computationally designed retroaldolase enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:4937–4942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913638107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, Doyle L, Roethlisberger D, Zanghellini A, Gallaher JL, Betker JL, Tanaka F, Barbas CF, III, Hilvert D, Houk KN, Stoddard BL, Baker D. De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes. Science. 2008;319:1387–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1152692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]