Abstract

Toxicity of the environmental carcinogen chromate is known to involve sulfur starvation and also error-prone mRNA translation. Here we reconcile those facts using the yeast model. We demonstrate that: (i) cysteine and methionine starvation mimic Cr-induced translation errors, (ii) genetic suppression of S starvation suppresses Cr-induced mistranslation, and (iii) mistranslation requires cysteine and methionine biosynthesis. Therefore, Cr-induced S starvation is the cause of mRNA mistranslation. This establishes a single, novel pathway mediating the toxicity of chromate.

Keywords: Chromate toxicity, sulfate transport, frameshift, Sul1, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

1. Introduction

Chromate [Cr(VI)] is a highly toxic metal species, linked to cancer among other conditions (Luippold et al., 2003; Urbano et al., 2008). Continuing industrial use of Cr and associated environmental pollution (Salnikow and Zhitkovich, 2008; Wise et al., 2009) reinforces an urgent need to resolve the cellular and molecular mechanism(s) of Cr toxicity, which remains unclear. Chromate is known to induce a range of types of DNA lesion in cells and also provokes protein oxidation (Peterson-Roth et al., 2005; Sumner et al., 2005; Reynolds et al., 2009). A role for protein dysfunction in Cr action was underscored by a recent genome-wide study with the yeast cell model, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Holland et al., 2007). That report revealed that Cr exposure provokes errors in mRNA translation, and that this is a major cause of Cr toxicity. Thus, Cr exhibited synergistic toxicity with a ribosome-targeting drug that is known to act via mistranslation, and manipulation of translational accuracy modulated Cr toxicity. However, the molecular mechanism by which Cr causes mistranslation was not resolved.

A further recent study demonstrated that Cr exposure leads to sulfur starvation in yeast, and that this also has deleterious consequences for growth (Pereira et al., 2008). This starvation arises because chromate inhibits sulfate uptake into cells, and may also compete with intracellular sulfate at the point of metabolism (Pereira et al., 2008; Alexander and Aaseth, 1995). Among other consequences, chromate-induced sulfur starvation is associated with depletion of the S-containing amino acids methionine (Met) and, in particular, cysteine (Cys) from cells (Pereira et al., 2008). This was of particular interest to us as amino acid starvation is a well described cause of translation infidelity; altering the competition between cognate and non-cognate aminoacyl-tRNAs at codons, to cause missense, frameshift and nonsense errors (Gallant and Lindsley, 1998; Farabaugh and Bjork, 1999; Sorensen, 2001).

In this short paper, we test the hypothesis that Met and Cys starvation arising during Cr exposure is the cause of Cr-induced mRNA mistranslation. The results showed this to be the case, reconciling these key recent findings to a single Cr toxicity mechanism in the yeast model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains and plasmids

Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4743 (MATa/α his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0 LYS2/lys2Δ0 met15Δ0/MET15 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0) was the parental background from which all strains were derived. A Met+/Cys+ prototrophic ‘wild type’ strain (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0) was selected after sporulation of BY4743. A Cys−/Met− auxotroph was obtained from the yeast deletion strain collection (Euroscarf, Germany) (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 met15Δ0 cys3∷KanMX4). Strains carrying the ade2-101 allele were generated as follows. A diploid strain carrying the ade2-101 allele and expressing a hemagglutinin(HA)-tagged Sul1 protein was obtained from Open Biosystems (Hunstville, AL): MATa/α ade2-101/ade2-101 HIS3/his3Δ200 leu2Δ98/leu2Δ98 lys2Δ801/lys2Δ801 ura3Δ52/ura3Δ52 trp1Δ1/TRP1 SUL1/HA-SUL1. This strain was sporulated and a MATα ade2-101 his3Δ200 leu2Δ98 lys2Δ801 ura3Δ52 HA-SUL1 strain selected, and crossed to S. cerevisiae BY4741 (Euroscarf) in order to obtain a strain that did not express HA-tagged Sul1p [confirmed by diagnostic PCR (Longtine et al., 1998)]. This strain was suitable for use in the qualitative nonsense suppression assay (MATα ade2-101 his3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ). Simultaneously, a strain was selected which carried the met15Δ0 allele (MATa ade2-101 his3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ met15Δ0). The CYS3 gene was knocked out in the latter using pFA6a-His3MX6 as the template for short flanking homology (SFH)-PCR based disruption (Longtine et al., 1998). This created a Cys−/Met− auxotroph expressing ade2-101 (MATa ade2-101 his3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ met15Δ0 cys3∷HIS5). All transformants (Gietz and Woods, 2002) were selected on yeast nitrogen base (YNB) without amino acids (Formedium), supplemented as required (Ausubel et al., 2007). Diagnostic PCR (Longtine et al., 1998) was used to confirm appropriate gene disruption. Where used, colony PCR for diagnosis involved heating a colony in 5 μl water for 5 min at 95°C, before using the entire sample as a template for PCR. A sul1Δ/sul2Δ double mutant (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 sul1∷KanMX4 sul2∷HphNT1) was constructed previously (Holland and Avery, 2009). Where indicated, strains were transformed with plasmid pYDL-TY1, which carries a dual-luciferase frameshift reporter construct (Harger and Dinman, 2003), or pDB868, which carries a dual-luciferase missense reporter (Salas-Marco and Bedwell, 2005).

2.2. Growth conditions, mistranslation assays and chromate uptake

Organisms were routinely maintained on YNB agar with appropriate supplements (Khozoie et al., 2009) and prepared for experiments by culturing from single colonies as starter cultures in YNB broth supplemented with Cys, Met or homocysteine where specified. Flasks were incubated with shaking at 120 rev. min-1, 30°C (Bishop et al., 2007). For quantitative determination of mistranslation, experimental cultures of strains carrying one of the mistranslation reporter plasmids (above) were inoculated from overnight starter cultures and pre-incubated as above for 4 h before the addition of CrO3 from filter-sterilized stock solutions. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and protein extracts prepared as described previously (Holland et al., 2007). Mistranslation was determined with the Dual Luciferase Assay system (Promega) exactly as described (Holland et al., 2007). The derived ratios of luminescence attributable to the firefly versus Renilla luciferases indicated the level of mistranslation.

For qualitative determination of nonsense codon mistranslation, cells expressing the ade2-101 allele were cultured to OD600∼2.0 in YPD broth (Khozoie et al., 2009) before spotting 10-fold serial dilutions on to YNB agar supplemented with Met and Cys as specified. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 4 d before image capture.

Cellular chromate uptake in experimental cultures was determined with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICPMS) (Thermo-Fisher Scientific X-SeriesII), exactly as described previously (Holland and Avery, 2009).

3. Results

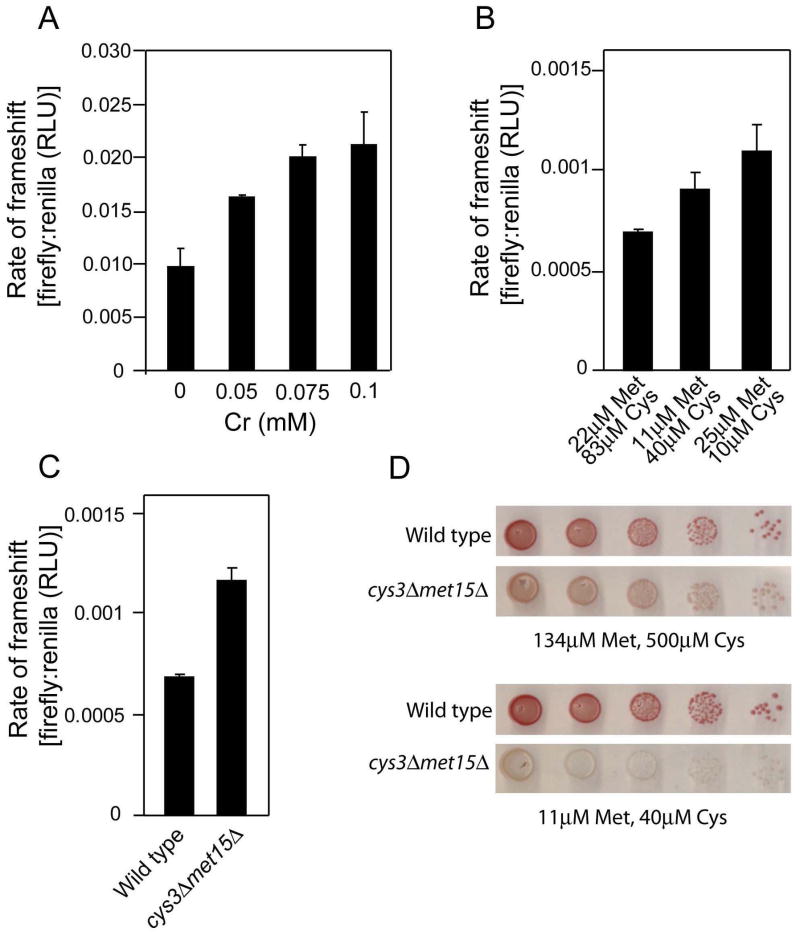

3.1. Met or Cys starvation mimics Cr-induced mRNA mistranslation

To test the hypothesis that Met and Cys starvation causes Cr-induced mRNA mistranslation, first we determined whether Met or Cys starvation was sufficient to mimic mistranslation. We measured frameshift error-rate using a reporter construct in which an upstream sequence encoding Renilla luciferase is separated from a downstream firefly luciferase by a programmed frameshifting ‘shifty’ sequence (Harger and Dinman, 2003); the firefly gene is out of frame with the Renilla gene, so frameshift errors are required to produce functional firefly luciferase. We found that exposure to CrO3 caused frameshift (Fig. 1A), missense (data not shown) and, previously (Holland et al., 2007), nonsense translation errors. We adopted the frameshift assay for routine measurement of mistranslation during the remainder of this study. In the presence of decreasing concentrations of Met and/or Cys supplied in the medium, even yeast cells which retained Met and Cys biosynthetic capacity exhibited increasing rates of mistranslation (Fig. 1B). The effect was similar to that of increasing Cr(VI) concentration (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the frameshift rate was elevated in a strain that was unable to synthesize its own Met or Cys (Fig. 1C). Increased mistranslation in the cys3Δ/met15Δ strain was evident also from a nonsense suppression assay (Fig. 1D), which is based on read-through of the ade2-101 UAA stop codon and suppression of the red pigmentation associated with this allele (Liu and Liebman, 1996; Holland et al., 2007). Thus, correct reading of the inserted stop codon leads to accumulation of purine precursors in the vacuole, and a red colony colour. A white colony colour indicates readthrough (mistranslation) of the stop codon, i.e. production of wild type Ade2p. The data substantiated that limitation of Met and Cys mimics the effect of Cr in promoting mRNA mistranslation (Fig. 1D). Note that we have also demonstrated Cr-induced mistranslation with the colour assay (Holland et al., 2007). That evidence counters the possibility that Cr-induced mistranslation detected with the luciferase assay (below) may merely reflect different stabilities of the Renilla and firefly proteins in the presence of Cr.

Fig. 1.

Met or Cys starvation mimics Cr-induced mRNA mistranslation. (A) S.cerevisiae BY4743 transformed with plasmid pYDL-TY1, which carries a dual-luciferase frameshift reporter construct, was cultured in YNB broth with appropriate supplements before treatment for 3 h with the indicated CrO3 concentrations and subsequent determination of luciferase activities. RLU, relative light units. All values are means ± SEM from at least three independent determinations. (B) Luciferase activities were from Met+/Cys+ prototrophs transformed with pYDL-TY1 and cultured overnight in YNB supplemented with Met and Cys as indicated. (C) Luciferase activities were from wild type Met+/Cys+ prototrophs and cys3Δ/met15Δ auxotrophic cells transformed with pYDL-TY1 and cultured overnight in YNB supplemented with 22μM Met and 83μM Cys. (D) A wild type Met+/Cys+ prototroph and a cys3Δ/met15Δ auxotrophic strain, both expressing the ade2-101 allele, were spotted in 10-fold serial dilutions on to YNB agar supplemented with Met and Cys as indicated. Images were captured after 4 d incubation at 30°C.

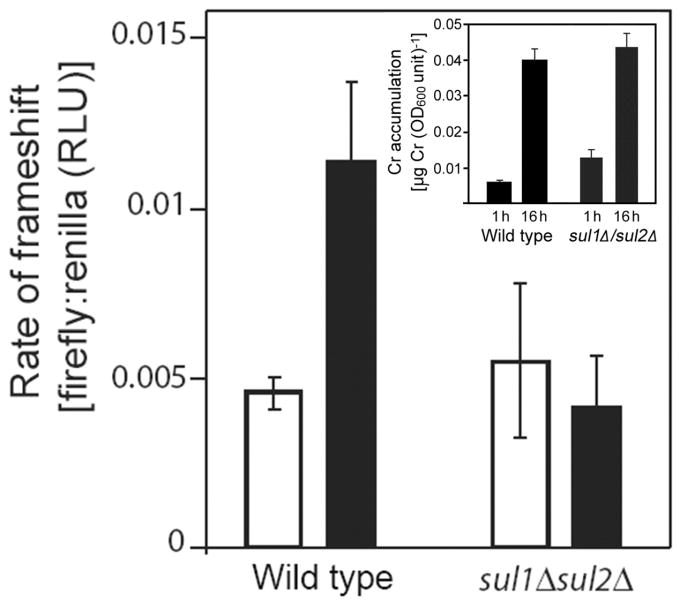

3.2. Chromate induced mistranslation requires the Sul1p/Sul2p transporters

Chromate causes sulfur (and hence Met and Cys) starvation primarily by inhibiting sulfate uptake via the Sul1p and Sul2p transporters in yeast (Pereira et al., 2008). Therefore, we reasoned that if S starvation is the cause of Cr-induced mRNA mistranslation, then this effect of Cr should be suppressed in a sul1Δ/sul2Δ double mutant. This was tested in medium lacking Met and Cys, to preclude any Sul1p or Sul2p down-regulation in the wild type control (Pereira et al., 2008). The marked increase in mistranslation rate caused by Cr in the wild type was absent in the sul1Δ/sul2Δ double mutant (Fig. 2). We discounted the possibility that this result for the mutant may have been a consequence of decreased Cr uptake [Cr transport in to yeast is partly mediated by Sul1p and Sul2p (Pereira et al., 2008; Holland and Avery, 2009)], as determination of cellular Cr levels revealed that Cr accumulation was no lower in the mutant than in the wild type under the present experimental conditions (Fig. 2, inset) [note that when we reproduced the experimental conditions described by Pereira et al. (2008), including homocysteine addition to the medium, we confirmed their observation that Cr accumulation in the sul1Δ/sul2Δ mutant was ∼50% of that in the wild type (data not shown)]. It should also be noted that other S acquisition pathways compensate for Sul1p and Sul2p in the double mutant, as the mutant is viable in medium lacking added Met or Cys. This may explain why the mistranslation rate in the mutant is lower than in Cr-exposed wild type cells (Fig. 2), the latter relying primarily on (Cr-inhibitable) Sul1p and Sul2p (Pereira et al., 2008; Holland and Avery, 2009). Collectively, the results supported the hypothesis that it is S starvation mediated via the yeast sulfate transporters that causes Cr-induced mistranslation.

Fig. 2.

Chromate induced mistranslation requires the Sul1p/Sul2p transporters. Wild type cells (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0) and a sul1Δ/sul2Δ double mutant were transformed with pYDL-TY1 and cultured in YNB broth, before treatment either without (open bars) or with (filled bars) 0.1 mM CrO3 for 3 h. Total protein was subsequently extracted for luciferase analysis. All values are means ± SEM from at least three independent determinations. Inset, cellular Cr levels were determined at the indicated intervals during Cr treatment of wild type and sul1Δ/sul2Δ cells, cultured as above.

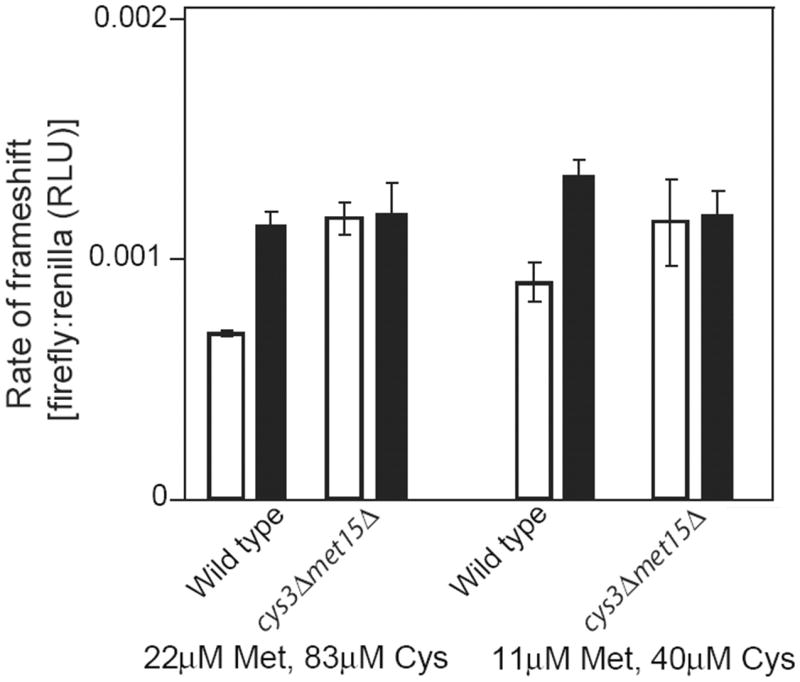

3.3. Chromate induced mistranslation requires Cys/Met biosynthesis

To support the above data, we exploited the Cys and Met auxotrophic strain, cys3Δ/met15Δ. For the hypothesis to be correct, Cr-induced mistranslation should be rescued in this mutant as it relies on exogenously-supplied Met and Cys, i.e., Met and Cys in the cys3Δ/met15Δ mutant do not arise from biosynthesis, so the levels of these amino acids are not affected by Cr-induced S starvation. Chromate exposure caused increased mRNA mistranslation in the control strain which biosynthesizes Met and Cys, but not in the cys3Δ/met15Δ mutant (Fig. 3). This result was reproducible at different external Met and Cys concentrations. The data indicate that the processes of Met and Cys biosynthesis are required for Cr to cause increased translation error-rate. This implicates these targets of Cr-induced S starvation (Pereira et al., 2008) as a cause of mistranslation.

Fig. 3.

Chromate induced mistranslation requires Cys/Met biosynthesis. Wild type cells (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0) and a cys3Δ/met15Δ auxotrophic mutant, both transformed with pYDL-TY1, were cultured for 16 h in YNB supplemented with Met and Cys as indicated and in the absence (open bars) or presence (filled bars) of 0.1 mM CrO3. Total protein was subsequently extracted for luciferase analysis.

4. Discussion

The evidence presented in this short paper embraces recent observations (Holland et al., 2007; Pereira et al., 2008) in allowing us to crystallize a complete pathway of Cr toxicity with the yeast model, as follows: (i) Chromate competes with sulfate for uptake into cells, causing S starvation and depletion of Met and Cys among other S metabolites (Pereira et al., 2008); (ii) Met and Cys depletion are responsible for elevated mRNA mistranslation that occurs during Cr exposure (present study) [the molecular mechanisms of loss of translation fidelity due to amino acid starvation have been described previously (Gallant et al., 1982; Gallant and Lindsley, 1998; Farabaugh and Bjork, 1999; Sorensen, 2001)] (iii) mRNA mistranslation leads to protein dysfunction including protein aggregation and causes Cr toxicity (Holland et al., 2007). This cements evidence from different labs into a unified model of Cr toxicity. Although the standard assays of translational fidelity used here record only a 2- to 3-fold induction of mistranslation by Cr, threshold effects are well known in metal toxicology (Avery et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2007) and our previous genetic and physiological evidence established that this induced rate of mistranslation is sufficient to cause Cr toxicity (Holland et al., 2007). One challenge that remains is to reconcile this novel protein-centred Cr toxicity mechanism with the previously-established DNA damage caused by Cr in yeast and other organisms (Voitkun et al., 1998; Peterson-Roth et al., 2005; Reynolds et al., 2009). This would help to elucidate how these differing targets may themselves combine to elicit cancer and the other deleterious consequences of chromate toxicity seen in higher organisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Environment Research Council (NE/E005969/1) and the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM57945). We also thank Jonathon Dinman (Univ. Maryland) for his kind gift of plasmid pYDL-TY1, and Ian Stansfield (Univ. Aberdeen) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Avery AM, Willetts SA, Avery SV. Genetic dissection of the phospholipid hydroperoxidase activity of yeast Gpx3 reveals its functional importance. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:46652–46658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J, Aaseth J. Uptake of chromate in human red blood cells and isolated rat liver cells: the role of the anion carrier. Analyst. 1995;120:931–933. doi: 10.1039/an9952000931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop AL, Rab FA, Sumner ER, Avery SV. Phenotypic heterogeneity can enhance rare-cell survival in ‘stress-sensitive’ yeast populations. Molecular Microbiology. 2007;63:507–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farabaugh PJ, Bjork GR. How translational accuracy influences reading frame maintenance. EMBO Journal. 1999;18:1427–1434. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant JA, Lindsley D. Ribosomes can slide over and beyond “hungry” codons, resuming protein chain elongation many nucleotides downstream. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1998;95:13771–13776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant J, Erlich H, Weiss R, Palmer L, Nyari L. Nonsense suppression in aminoacyl-t-RNA limited cells. Molecular and General Genetics. 1982;186:221–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00331853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Woods RA. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods in Enzymology. 2002;350:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harger JW, Dinman JD. An in vivo dual-luciferase assay system for studying translational recoding in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA. 2003;9:1019–1024. doi: 10.1261/rna.5930803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland S, Avery SV. Actin mediated endocytosis limits intracellular Cr accumulation and Cr toxicity during chromate stress. Toxicological Sciences. 2009;111:437–446. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland S, Lodwig E, Sideri T, Reader T, Clarke I, Gkargkas K, Hoyle DC, Delneri D, Oliver SG, Avery SV. Application of the comprehensive set of heterozygous yeast deletion mutants to elucidate the molecular basis of cellular chromium toxicity. Genome Biology. 2007;8 doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-12-r268. Art. no. 268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khozoie C, Pleass RJ, Avery SV. The antimalarial drug quinine disrupts Tat2p-mediated tryptophan transport and causes tryptophan starvation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:17968–17974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.005843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Liebman SW. A translational fidelity mutation in the universally conserved sarcin/ricin domain of 25S yeast ribosomal RNA. RNA. 1996;2:254–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen MA. Charging levels of four tRNA species in Escherichia coli Rel+ and Rel− strains during amino acid starvation: A simple model for the effect of ppGpp on translational accuracy. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;307:785–798. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luippold RS, Mundt KA, Austin RP, Liebig E, Panko J, Crump C, Crump K, Proctor D. Lung cancer mortality among chromate production workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2003;60:451–457. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.6.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Y, Lagniel G, Godat E, Baudouin-Cornu P, Junot C, Labarre J. Chromate causes sulfur starvation in yeast. Toxicological Sciences. 2008;106:400–412. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson-Roth E, Reynolds M, Quievryn G, Zhitkovich A. Mismatch repair proteins are activators of toxic responses to chromium-DNA damage. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2005;25:3596–3607. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3596-3607.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds MF, Peterson-Roth EC, Bespalov IA, Johnston T, Gurel VM, Menard HL, Zhitkovich A. Rapid DNA double-strand breaks resulting from processing of Cr-DNA cross-links by both MutS dimers. Cancer Research. 2009;69:1071–1079. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Marco J, Bedwell DM. Discrimination between defects in elongation fidelity and termination efficiency insights into translational provides mechanistic readthrough. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;348:801–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salnikow K, Zhitkovich A. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in metal carcinogenesis and cocarcinogenesis: Nickel, arsenic, and chromium. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2008;21:28–44. doi: 10.1021/tx700198a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MC, Sumner ER, Avery SV. Glutathione and Gts1p drive beneficial variability in the cadmium resistances of individual yeast cells. Molecular Microbiology. 2007;66:699–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner ER, Shanmuganathan A, Sideri TC, Willetts SA, Houghton JE, Avery SV. Oxidative protein damage causes chromium toxicity in yeast. Microbiology. 2005;151:1939–1948. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27945-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbano AM, Rodrigues CFD, Alpoim MC. Hexavalent chromium exposure, genomic instability and lung cancer. Gene Therapy and Molecular Biology. 2008;12B:219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Voitkun V, Zhitkovich A, Costa M. Cr(III)-mediated crosslinks of glutathione or amino acids to the DNA phosphate backbone are mutagenic in human cells. Nucleic Acids Research. 1998;26:2024–2030. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.8.2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise JP, Payne R, Wise SS, Lacerte C, Wise J, Gianios C, Thompson WD, Perkins C, Zheng T, Zhu C, Benedict L, Kerr I. A global assessment of chromium pollution using sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) as an indicator species. Chemosphere. 2009;75:1461–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]