Abstract

Low-frequency fatigue (LFF) is characterized by a proportionally greater loss of force at low compared to high activation frequencies and a prolonged recovery. Recent work suggests a calcium-induced uncoupling of excitation-contraction coupling underlies LFF. Here newly characterized triadic proteins are described and possible mechanisms by which they may contribute to LFF are suggested.

Keywords: Sarcoplasmic reticulum, Ryanodine receptor, Junctophilin, Mitsugumin, JFP-45, Calcium channels

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle fatigue has been defined as the transient, work-induced inability to maintain the expected or required force or power output. The potential mechanisms underlying the impaired muscle function during fatigue are varied and include decreased central nervous system drive, impaired neuromuscular transmission, alterations in the muscle surface and transverse-tubule (t-tubule) membrane action potential, impaired excitation-contraction coupling (ECC), decreased calcium (Ca2+) sensitivity of contraction, and impaired cross-bridge function (for review see (1)). The relative importance of each of these factors depends on the type and duration of the work bout that induced the fatigue, environmental conditions, and the nutritional state and training status of the individual. The characteristics of fatigue, i.e., changes in contractile properties, electromyography, force-frequency relationship, and duration of impairment, will vary according to the underlying impairment and therefore provide mechanistic insight.

LOW FREQUENCY FATIGUE

Low frequency fatigue (LFF) is characterized by a prolonged recovery and selective loss of force at low frequencies of activation (Fig. 1A) regardless of the protocol used to induce fatigue (1). Indeed, a work-induced decrease in the ratio of force production in response to 20-Hz or 30-Hz stimulation versus. 100-Hz is commonly used to define LFF. Although the initial characterization of LFF, which utilized human subjects, included continuous low-frequency stimulation of a small muscle, the work also described LFF in response to voluntary isometric and dynamic contraction of a large muscle group. It is now clear that LFF occurs in humans in response to voluntary contractions (1).

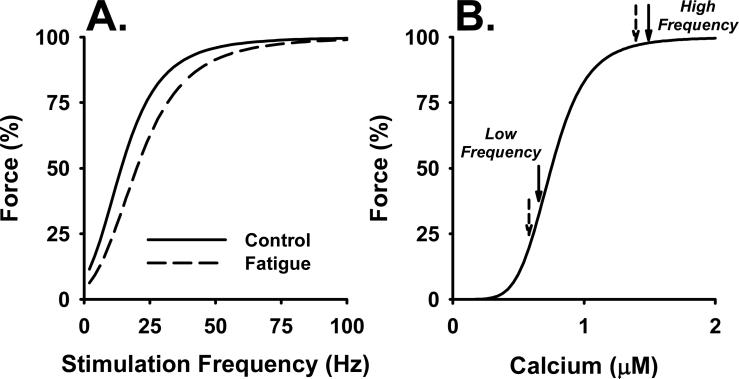

Figure 1.

Force-frequency (A) and force-calcium (B) relationships. A. There is a sigmoid relationship between stimulation frequency and force generated by a muscle. Although the shape of the relationship is similar in vivo and in vitro and between fiber types, the precise values for the stimulation frequencies vary and are an approximation in this figure. The solid line illustrates the force-frequency relationship for a nonfatigued muscle. The dashed line illustrates the characteristic decline in force at low activation frequencies that occurs during low-frequency fatigue. B. The sigmoid relationship between calcium and force can give rise to the shift in the force-frequency curve as illustrated in (A). A uniform decline in the intracellular calcium (Ca2+) transient at all stimulation frequencies will cause force to fall along sigmoid curve as illustrated by the solid arrows. At high activation frequencies, the decline in Ca2+ occurs along the plateau of the curve and will have little effect of force; compare high frequency solid (control) and dashed (fatigue) arrows. In contrast, a similar relative decline in Ca2+ release at lower activation frequencies will fall along the steep part of the relationship and will cause a substantial decline in force (compare low frequency solid and dashed arrows).

LFF may be functionally significant, as the motor discharge rate during voluntary muscle activation rarely exceeds 30 Hz (1), an activation frequency at which LFF is manifest. Increased motor drive may compensate for the decreased force generation at low activation frequencies and thereby maintain force. However, the increased CNS activation may cause subjects to experience a greater sense of effort and increased fatigability during normal daily activities. Further, LFF of the respiratory muscles occurs after exhaustive respiratory effort and has therefore been suggested to be of clinical significance in respiratory failure (26).

A number of characteristics of LFF give clues as to the underlying mechanisms (1). First, involvement of the central and peripheral nervous system are excluded due to the lack of significant alterations in the electromyogram associated with LFF. Muscle metabolite levels return to near resting levels early in recovery while force remains significantly depressed, thus a metabolic mechanisms is excluded. Further, because this type of fatigue has been induced in isolated muscles and single muscle fibers, the mechanism underlying LFF must lie within the muscle fiber itself. The long-lasting nature of LFF precludes muscle membrane depolarization and alterations in the action potential as probable causes, because these derangements recover rapidly upon the cessation of work. The observation that LFF in isolated muscles was completely reversed by the ryanodine receptor (RyR) activator caffeine suggested an impairment in ECC as the underlying mechanism. Finally, the prolonged recovery suggests a protein modification, possibly requiring protein synthesis to restore force.

Evidence to date suggests a functional uncoupling of excitation from contraction related to an elevated Ca2+ concentration in the triadic junction. However, the mechanism and targets of the Ca2+-dependent process are unknown. Likely candidates include the transverse-tubule (ttubule) voltage sensor (also know as. L-type Ca2+ channel and dihydropyridine receptor, DHPR) and RyR1 Ca2+ release channel in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), yet other recently discovered “minor” triadic proteins may be involved and are currently being characterized. Some of these minor proteins appear to be critical for the structural integrity of the triad and for the functional coupling of the DHPR and RyR, and therefore have a potential role in excitation-contraction uncoupling in LFF, eccentric muscle contraction-induced muscle weakness, and aging. Rather than focus on the major triadic proteins, the DHPR and RyR1, which appropriately receive a great deal of attention, this review will focus on the potential role of the minor proteins in LFF. First, the mechanism of skeletal muscle ECC and the role of the DHPR and RyR1 will be reviewed, then the evidence for excitation-contraction uncoupling in LFF will be described. This will be followed by a discussion of many of the recently characterized triadic proteins, and finally potential roles these proteins could play in LFF will be suggested.

EXCITATION-CONTRACTION COUPLING

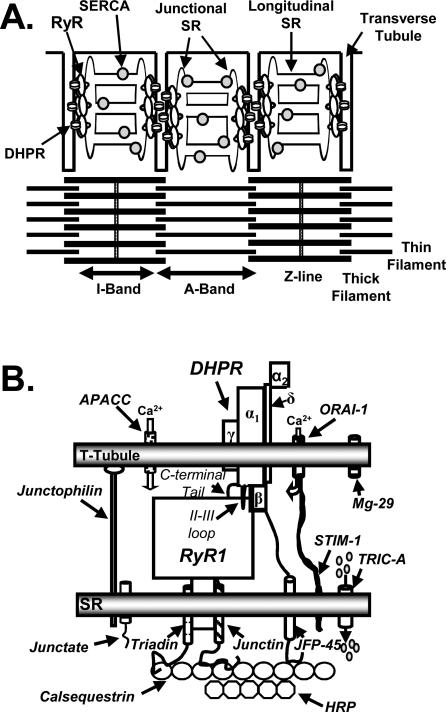

ECC occurs at the interface of two membrane systems, the invaginations of the surface membrane known as t-tubules and the intracellular SR (Fig. 2A). The SR is a specialized form of endoplasmic reticulum (ER), dedicated to the storage and release of Ca2+ for the regulation of muscle contraction. The SR can be divided into two domains, the longitudinal SR and the junctional SR. The longitudinal SR made up of a network of interconnected tubules enriched in proteins involved in uptake of Ca2+ into the SR such as the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA). As the longitudinal SR approaches the t-tubule, the tubules coalesce into an enlarged sac known as the terminal cisterna. The region of the terminal cisterna facing the ttubule is the junctional face membrane. At the junction of A and I bands in mammalian skeletal muscle, two terminal cisternae and one t-tubule make up the triad. Numerous proteins, many of them uncharacterized, are found in triad preparations (Fig 2B). Of primary importance are the L-type Ca2+ channel in the t-tubule membrane and the RyR in the junctional face membrane. Depolarization of the t-tubule membrane induces a conformational change in the L-channel which in turn opens RyR1 allowing Ca2+ efflux from the SR (21).

Figure 2.

Skeletal muscle intercellular membrane system and triadic proteins. A. The sarcoplasmic reticulum can be divided into two distinct regions, the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) which contains the ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and is the site of calcium (Ca2+) release and a network of longitudinal SR which is enriched in sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA). In mammalian skeletal muscle the triad, which is composed of a transverse-tubule (t-tubule) abutted on each side by junctional SR is located at the edge of the A band. B. Triadic proteins. For clarity, only one of the four dihydropyridine receptors (DHPRs) that contact the RyR1 is shown. APACC, action-potential activated Ca2+ channel; MG-29, mitsugumin 29 kDa; STIM-1, Stromal interaction molecule 1; TRIC-A, trimeric intracellular cation-selective channel A; HRP, histidine-rich Ca2+ binding protein; JFP-45, junctional face protein 45 kDa. See text for details.

Ryanodine Receptors

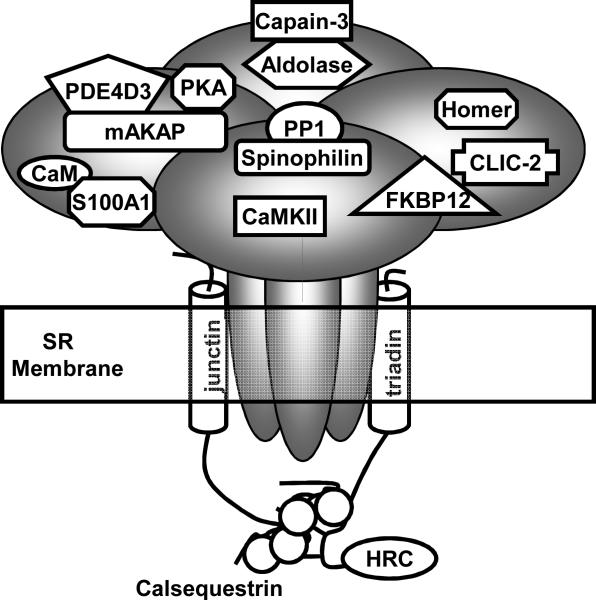

In mammals there are three RyR isoforms (for review see (13)). RyR1 and RyR2 are the predominant isoforms skeletal and cardiac muscle, respectively. RyR3 has a wide tissue distribution and is expressed at very low levels in skeletal muscle. RyRs are homotetrameric channels. Each monomer consists of >5,000 residues and has a molecular mass of approximately of 565 kDa. RyRs are arranged in lattice-like arrays in the junctional face membrane where they contact their neighbors at the corners and every other RyR1 is coupled to a DHPR tetrad. The carboxy-terminal third of the channel spans the SR (Fig. 3). The amino two-thirds of the protein is cytoplasmic, makes critical interactions with the DHPR and provides a scaffolding to support numerous accessory proteins. Some of the accessory proteins are involved in the phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of the channel, including cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and phosphodiesterase 4D3 (PDE4D3), Ca/calmodulin dependent protein kinase (CaMKII), and protein phosphatase 1 (PP1). The EF-hand Ca2+-binding proteins, calmodulin (CaM) and S100A1 modulate Ca2+ activation of RyR1 and may compete for the same binding site on the channel. In vitro, both these proteins enhance channel opening in nM Ca2+ (near resting intracellular Ca2+ concentrations) (13,32). Although genetic ablation of CaM is lethal, S100A1 knock-out animals are viable and exhibit reduced voltage-activated SR Ca2+ release (27). Thus disrupting the interaction between CaM or S100A1 and RyR1 would be predicted to depress SR Ca2+ release. Further, oxidation of CaM (4) or oxidation, nitrosylation or glutathionylation of RyR1 (3) reduces CaM regulation of the channel. Similar work has not been performed with S100A1. The FK506-binding protein FKBP12 is thought to stabilize the tetrameric channel and aid in coordinated gating. The function of the glycolytic enzyme aldolase is unclear, but it may serve as an anchor for the neutral Ca2+-activated protease calpain-3. A soluble form of the chloride intracellular channel (CLIC-2) binds RyR1 and stabilizes the closed state of the channel (22). The channel also interacts with the SR membrane proteins triadin and junctin which in turn interact with calsequestrin and histidine-rich calcium binding protein (HRC). Calsequestrin and HRC are low-affinity, high capacity Ca2+ binding proteins that act to buffer the free Ca2+ concentration within the SR lumen. Homer1 is a scaffolding protein that has been reported to enhance RyR1 activation (12). However, more recently Homer1 has been localized to the z-disk where its putative function is to link mechanical stretch to the activation of mechanosensitive channels (31).

Figure 3.

The skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor (RyR1) and associated proteins. Each of the four RyR1 monomers binds one of each of the accessory proteins except for calsequestrin and histidine-rich calcium binding protein (HRC). For clarity, only one of each of the proteins is shown. CaM, calmodulin; CaMKII, Ca2+ /calmodulin dependent protein kinase; PKA, cAMP-dependent protein kinase; PDE4D3, phosphodiesterase; FKBP12, FK506-binding protein 12 kDa; PP1, protein phosphatase 1; mAKAP, cAMP kinase anchoring protein; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; CLIC-2, chloride intracellular channel.

In vivo RyR1 is activated via the voltage-driven conformational change in the DHPR, however, in vitro, RyRs can be activated in a biphasic manner by Ca2+ (13). In the absence of other channel regulators RyR1 is closed at resting cytoplasmic Ca2+ (approximately 50 nM). As the Ca2+ on the cytoplasmic face of the channel increases into the μM range channel opening increases and reaches a peak at a Ca2+ concentration near 0.1 mM. Further increases in Ca2+ progressively close the channel. This biphasic Ca2+ dependence is modulated by numerous endogenous ligands including adenine nucleotides and magnesium which enhance and inhibit channel opening respectively (13).

L-Type Ca2+ Channel (DHPR)

In skeletal muscle the L-type Ca2+ channel is located primarily in the t-tubule and is composed of five subunits, a pore-forming α1 (Cav1.1), an intracellular β, a membrane spanning γ, and an extracellular α2 which is linked via a disulfide bond to a membrane spanning δ subunit. The α1 subunit is composed of four repeating motifs (I-IV) of six transmembrane α-helices (S1-S6). The S4 α-helix of each repeating motifs is highly positively charged and imparts voltage-sensitivity to the channel. A hairpin-loop between S5 and S6 forms part of the channel pore. DHPRs in the t-tubule oligomerize into tetrads with each of the four DHPRs making multiple contacts with RyR1 (5). These contacts involve the intracellular loop between the repeat motifs II and III of α1, the α1 carboxy-terminal tail, and the β-subunit (Fig. 2B). The contacts transduce the depolarization-induced conformational change in the DHPR to RyR1. Thus, weakening these interactions would decrease the efficiency of ECC and impair force development.

In vitro, two electrical signals originating from the DHPR can be recorded; the t-tubular charge movement and the L-type Ca2+ current (for details see (21)). The t-tubular charge movement originates in the voltage-driven translocation of charges, predominately within the four S4 α-helices, across the electrical field of the t-tubular membrane. The L-current is carried by the influx of Ca2+ from the t-tubular lumen into the triadic junction. The charge movement is an absolute requirement for skeletal muscle ECC. The function of the L-current is unclear as extracellular Ca2+ can be removed without abolishing contraction.

Ca2+ Fluxes Across the Transverse-Tubule Membrane

A number of pathways for Ca2+ influx across the surface membrane and t-tubules have recently been identified (for details see (10)). In nonexcitable cells, depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores triggers the influx of Ca2+ across the plasma membrane to refill the depleted store, i.e. store-operated Ca2+-entry (SOCE). Recently SOCE has been clearly demonstrated in skeletal muscle. The two primary components underlying SOCE, stromal interaction molecule 1 (Stim1) the Ca2+ store sensor, and Orai1 a component of the SOCE channel, are highly expressed in skeletal muscle. Stim1 co-localizes with RyR1. SOCE in skeletal muscle occurs across the ttubule membrane, is controlled by the Ca2+ content in the region of SR adjacent to each section of t-tubule and can be activated by individual Ca2+ release events prior to exhaustion of the SR Ca2+ store.

A role for SOCE in muscle fatigue comes from observation that muscle with reduced Stim 1 expression generated lower maximal tetanic tension and fatigued more rapidly than muscle with normal Stim 1 content. The increase susceptibility to fatigue was associated with an inability to maintain SR Ca2+ stores. Thus, SOCE is required to sustain SR Ca2+ stores during repeated contractions (10).

Excitation-coupled Ca2+ entry (ECCE) is a store-independent Ca2+ entry pathway that is activated upon prolonged or repetitive depolarization (10). The molecular entities underlying this current are not well defined. The current requires functionally coupled RyRs and DHPRs and is independent of Stim1 and Ori1. It may be mediated by the L-type Ca2+ channel or an as of yet unidentified Ca2+-permeable channel within the t-tubule and coupled to the RyR-DHPR complex.

Launikonis et al. (19) described a small action-potential mediated Ca2+ influx across the t-tubule membrane that could not be ascribed to any known skeletal muscle ion channel. The current rapidly inactivates and therefore raises the Ca2+ concentration in the triadic junction only during the initial action potential of a train. The authors speculate that this Ca2+ influx primes the RyRs to activation by the DHPR.

EXCITATION-CONTRACTON UNCOUPLING IN LFF

In general, three different preparations have been used to study the cellular mechanisms underlying LFF, in vivo exercise in conjunction with skeletal muscle biopsies, isolated whole muscles or individual muscle fibers, and mechanically peeled muscle fibers. After dynamic knee extensor exercise which reduced evoked isometric tension at stimulation frequencies of 10 and 20 Hz stimulation but not at 50 or 100 Hz, Hill et al. (14) obtained biopsies of the vastus lateralis. In this preparation, SR function from fresh and fatigued muscle was studied under identical conditions eliminating any metabolic or ionic influences. Low-frequency fatigue resulted in a reduced rate of SR Ca2+ release and a reduced rate of Ca2+ uptake back into the SR. In spite of the depressed rate of Ca2+ uptake, there was no difference in the rate of adenosine-5'-triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis by SERCA, suggesting there was either an uncoupling of Ca2+ transport from ATP hydrolysis by the pump or there was an increased leak of Ca2+ out of the SR. Furthermore, there was a significant correlation between the decreased ratio of torque generated at 20:50 Hz and the rate of SR Ca2+ release but no relationship was found between the rate of Ca2+ uptake and muscle relaxation or rate of torque generation. These authors concluded that modification of the RyR protein contributed to LFF. An obvious limitation to this type of work is that SR Ca2+ release could not be triggered via the normal DHPR-RyR coupling.

To circumvent this limitation, intact mouse muscle fibers were intermittently stimulated and isometric tension and intracellular Ca2+ were simultaneously recorded (1). The induction of LFF was exemplified by a long lasting, reduction in isometric tension at low stimulation frequencies. There was no change in Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction or maximal tension. Conduction of the action potential into the depths of the t-tubule was not impaired as the reduction in tetanic Ca2+ across the width of the muscle fibers was uniform. In addition, direct activation of RyR1 with caffeine restored tension in the fatigued muscle demonstrating that SR Ca2+ stores were not depleted. Thus, the main cause of LFF in these intact fibers was a reduction in SR Ca2+ release, which in conjunction with the sigmoid Ca2+ dependence of contraction, caused the loss of force at low stimulation frequencies.

As illustrated in Figure 1B, because of the sigmoid force-Ca2+ relationship, a decrease in the intracellular Ca2+ transient could give rise to LFF. In fresh muscle (solid arrows), high frequency stimulation elicits a Ca2+ transient that falls on the plateau of the force-Ca2+ curve. Although fatigue may reduce the Ca2+ transient in response to high-frequency stimulation, it would still fall near the plateau of the force-Ca2+ curve and tension would be maintained (dashed arrow). In contrast, the Ca2+ transient elicited by low-frequency stimulation falls on the steep section of the curve. A reduction in the Ca2+ transient here would cause significant reduction in force (Fig. 1B, low-frequency solid vs dashed arrow).

An advantage of intact muscle fibers is that the physiological ECC mechanism remains intact; however, a limitation is the inability to manipulate the intracellular environment to study the mechanisms underlying LFF. Peeled muscle fibers maintain the DHPR-RyR coupling mechanism and allow manipulation of the cellular environment. In this preparation, a segment of muscle fiber is isolated and the surface membrane is mechanically peeled from the fiber. When the surface membrane tears away from the t-tubules, the t-tubule membrane seals over and traps the extracellular solution in the t-tubule lumen. The t-tubules can then be polarized and depolarized via ion substitution in the bath media and because the link between the DHPR and RyR remains intact SR Ca2+ release can be induced via the physiological ECC pathway.

A Ca2+-induced uncoupling of ECC was demonstrated in mechanically peeled muscle fibers (1). The uncoupling was Ca2+ and time dependent and could be induced upon a 60 sec exposure to 2.5 μM Ca2+, a physiologically relevant Ca2+ concentration. Furthermore, the temperature and pH dependence of the uncoupling suggested an enzymatic process. However, Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation or de-phosphorylation were not involved in the process as neither removal of ATP to prevent phosphorylation, nor phosphatase inhibition prevented the Ca2+-induced uncoupling. Similarly, oxidation was excluded as a mechanism because the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) did not significantly alter the process. Later work suggested a role for the Ca2+-dependent proteases known as calpains (34).

Simultaneous recordings of force and intracellular Ca2+ in single muscle fibers supported the hypothesis of Ca2+-induced ECC-uncoupling in LFF (1). A threshold Ca2+-time integral required to induce ECC-uncoupling was defined by varying the duty cycle of the stimulation protocol and including caffeine in some of the bath solutions. Stimulation protocols that exceeded the threshold induced LFF.

Although Bruton et al. (6) confirmed the role of reduced Ca2+ release in LFF in mouse fibers which generate little reactive oxygen species (ROS) during fatiguing stimulation; they also showed that in rat fibers, which do generate ROS, there was a reduction in the Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction. In addition, the reduced Ca2+ sensitivity but not the depressed SR Ca2+ release could be partially reversed by reducing agents. Thus, the work-induced decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity was attributed to ROS but the mechanism underlying the reduced Ca2+ release remained unclear.

Taken together, this work suggests that depressed SR Ca2+ release and possibly a reduced Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction make a significant contribution to the development of LFF. Although there may be a small reduction in the rate of SR Ca2+ uptake, it is not sufficient to reduce SR Ca2+ load to the point where release is significantly impaired. Because LFF can be overcome by a strong activating stimulus, e.g. high frequency stimulation or caffeine, the impaired SR Ca2+ release can be attributed to a decrease in the strength of the functional coupling between the DHPR and the RyR. Further, the uncoupling appears to be a Ca2+-mediated process. Before addressing mechanisms by which elevated triadic Ca2+ might impair ECC the newly characterized triadic proteins that might be involved in maintaining efficacy of ECC will be reviewed.

MINOR TRIADIC PROTEINS

In myotubes devoid of RyR1 or DPHR, the SR and t-tubules still arrange into triads. Conversely, when RyR1 and the DHPR are heterologously co-expressed triads are not formed, the proteins remain uncoupled and depolarization-induced Ca2+ release is not reconstituted. These results catalyzed the search for proteins required for triad formation. Although the DHPR and RyR are the best characterized, numerous other proteins are present in the skeletal muscle triad. A number of these proteins have been characterized and their role in ECC investigated (33). Some of them have been associated with impaired muscle function associated with aging or eccentric-contractions. The location of many of these proteins is illustrated in Figure 2B and their putative functions are described below.

Junctophilin is a single transmembrane domain SR protein. The carboxy-terminal is located within the SR while the amino terminal interacts with the cytoplasmic face of the t-tubule membrane via a 14 residue MORN (Membrane Occupation and Recognition Nexus) motif (33). There are four isoforms, JP-1,-2,-3, and -4. JP-1 is expressed exclusively in skeletal muscle. JP-2 is expressed in cardiac, skeletal and smooth muscle. Suppression of JP-1 and -2 in mature skeletal muscle resulted in deformed triads, reduced SOCE, and decreased SR Ca2+ stores (16). Thus, JP-1 and -2 are critical for the formation and maintenance of the skeletal muscle triad. Recently, we have shown that JP-1 and JP-2 content is reduced in adult skeletal muscle following a bout of eccentric muscle contractions, at a time when tetanic tension was significantly reduced. Furthermore, there was a significant correlation between the magnitude of the strength deficit and the reduction in JP-1 and JP-2 content (8). Although the aim of that work was to induce muscle damage rather than LFF, the two phenomena may share an underlying impairment, namely excitation-contraction uncoupling.

Junctional Face Protein 45 kDa (JFP-45) (not to be confused with junctophilins) is also a single transmembrane protein linking the SR and t-tubules. It interacts, via its C-terminal, with calsequestrin in the lumen of the SR and with the DHPR via its N-terminal (2). JFP-45 knock-out mice are viable but exhibit reduced voluntary wheel running and muscle weakness. The weakness was associated with decreased Cav1.1 expression, reduced t-tubular charge movement, and reduced depolarization-induced Ca2+ release but normal RyR expression (9). Thus, JFP-45 is thought to target Cav1.1 to the t-tubule and to maintain the DHPR complex.

Mitsugumin-29 (Mg-29; mitsugumi means triad junction in Japanese) is a 29 kDa four transmembrane domain t-tubular protein (33). In micrographs of the triad, the t-tubules appear elongated to provide a greater interface with the junctional face membrane of the SR. Deletion of Mg-29 resulted in swollen t-tubules, vacuolated SR, and misaligned triads, thus Mg-29 is thought to maintain the t-tubules in the elongated conformation that allows triad formation (23). Deletion of Mg-29 significantly impaired SOCE in myotubes and increases susceptibility to fatigue in mature muscle (25).

Triadin (TRISK) was initially thought to be a skeletal muscle specific protein, it is now understood that triadin is expressed in numerous tissues and the triadin gene can undergo multiple splicings to generate at least four isoforms, Trisk95 (Triadin Skeletal 95 kDa; the initial triadin identified), Trisk51, Trisk49, and Trisk32 (20). All four isoforms have a single transmembrane domain, a short cytoplasmic domain, and a long SR luminal tail. Trisk95 and -51 are localized to the terminal cisternae while trisk32 is located throughout the SR. When located in the terminal cisternae, trisks are associated with RyR1 and may bind calsequestrin.

Two groups (24,30) generated pan-triadin knock-out animals and reported similar results. In fast- but not slow-twitch skeletal muscle there were subtle alterations in the architecture of triads in which the t-tubules were oriented longitudinally or obliquely rather than transversal. Although calsequestrin content was reduced, it was properly localized to the terminal cisternae. As a consequence of the reduce calsequestrin content, the SR Ca2+ stores were reduced. Interestingly, the mice generated by Oddoux et al. (24) but not those of Shen et al (30) exhibited muscle weakness, performing worse than wild type animals on both in vivo and in vitro tests of strength. Both groups concluded that triadins are required for the proper arrangement of the triad and for normal expression of calsequestrin. Further, if triadins are involved in anchoring calsequestrin at the terminal cisternae, an additional protein, possibly junctin must also be involved.

Alternative splicing of the aspartyl-β-hydroxylase gene results in one of four single transmembrane domain proteins, aspartyl-β-hydroxylase, humbug, junctate or junctin. Junctin and junctate are localized to the skeletal muscle triad (33). Junctin has a short cytoplasmic domain, a long SR luminal tail, and binds RyR1 and calsequestrin. It may communicate the extent of SR Ca2+ load to the RyR1. Junctate is a 33 kDa single transmembrane domain SR protein. The carboxy-terminal tail, within the SR lumen, has a moderate affinity and high capacity for Ca2+ binding. Over expression in skeletal muscle increased SR Ca2+ load and enhanced RyR1 mediated Ca2+ release.

Trimeric intracellular cation selective channels (TRIC) are ubiquitously expressed homotetrameric proteins localized to the SR, endoplasmic reticulum, and nuclear membranes. TRIC-B is the common form. TRIC-A (also know as SRP-27 and mitsugumin-33) is specific to excitable tissue and is expressed at higher levels in fast-twitch than in slow twitch muscle. In planar lipid bilayer experiments, TRIC-A is selective for monovalent cations and has single channel characteristics similar to those described for the SR K+ channel. TRIC-A may mediate cationic countercurrent required to prevent the development of a negative SR membrane potential upon the release of Ca2+ from the SR (35).

Glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes are associated with SR membranes and are thought to maintain the local concentration of ATP at a level sufficient for optimal SERCA activity. Some of these enzymes may also play a structural role in the maintenance of the triad. Aldolase, for example, is physically associated with RyR1 (19).

Calpain-3 is a member of the calpain family of neutral Ca2+ dependent proteases. A fraction of the muscle calpain-3 localizes to the triad and associates with aldolase and the RyR. Aldolase, RyR1 content, and SR Ca2+ release are reduced in skeletal muscle from calpain-3 deficient animals suggesting calpain-3 may play a role in the structural stability of the triad (19).

POTENTIAL TARGETS AND MECHANISMS

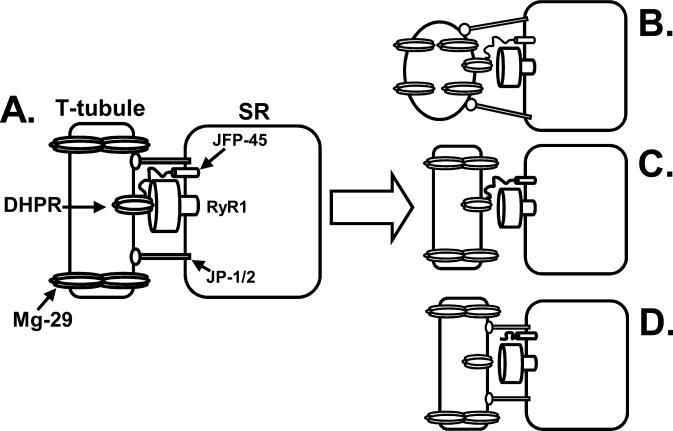

The characteristics of LFF, in particular the apparent lack of effect of LFF on SR Ca2+ stores, provide some insight into potential targets among the minor triadic proteins. The relatively minor effect of LFF on force production at high stimulation frequencies and the ability of caffeine to restore force during LFF demonstrate that there is sufficient Ca2+ within the SR to fully activate contraction. Thus, modification of components of the store-operated, excitation-coupled, and action-potential activated Ca2+ entry pathways do not significantly contribute to LFF. Similarly, the counter current required for SR Ca2+ release (which may be mediated in part by TRIC-A) does not appear to be impaired because activation of RyR1 rather than flux through the open channel is impaired. Therefore, the minor triadic proteins thought to play a role in maintaining the structural integrity of triads, such as junctophilin-1 and -2 (16,17), JFP-45 (9) and Mg-29 (23), are the likely candidates to be involved in LFF-induced excitation-contraction uncoupling (Fig. 4). The components of the triad that maintain the DHPR and RyR1 in the proper position and conformation for the functional coupling of these two channels are unknown. However, it is clear from heterologous co-expression experiments that the two channels alone are insufficient. The junctophilins appear to function as a bridge between the t-tubule and SR and maintain the proper distance between the DHPR and RyR1. By maintaining the elongated structure of the t-tubules, Mg-29 also contributes to the proper alignment of the DHPR and RyR1. Thus, alterations in any of these proteins could significantly alter the architecture of the triad and decrease the efficacy of ECC (Fig. 4B and C). Indeed our work has shown that the eccentric contraction-induced force decline correlated with the loss of JP-1 and JP-2. In addition, muscle from animals lacking Mg-29 exhibit a force-frequency relationship that is reminiscent of LFF. Similarly, given that JFP-45 spans the SR membrane and maintains the DHPR complex, disruption of JFP-45 may decrease the efficacy of coupling by altering the conformation or alignment of the DHPR (Fig. 4C). The ill-defined modifications that disrupt the function of these proteins could be alterations in the proteins themselves, altered protein-protein interactions or particularly in the case of the junctophilins, altered protein-lipid interaction. Whichever modification occurs, it appears to be initiated by a rise in triadic Ca2+. Elevated triadic Ca2+ could initiate a number of pathways leading to reduced efficacy of ECC. Likely candidates include activation of calpains, phospholipase A, protein kinase C, and increased mitochondrial ROS production.

Figure 4.

Potential role for minor triadic proteins in low-frequency fatigue (LFF)-induced excitation-contraction uncoupling. A. Prior to LFF the dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) and ryanodine receptor (RyR1) are functionally coupled. The elongated conformation of the transverse-tubule (t-tubule) is maintained by mitsugumin-29 (Mg-29). Junctophilin-1 and -2 (JP-1/2) maintain the proper alignment between the t-tubule and junctional face protein 45 kDa (JFP-45) is important for the functional expression of the DHPR. B. Disruption of Mg-29 allows the ttubule to adopt a conformation unfavorable to functional coupling of the DHPR and RyR1. C. Loss of JP-1/2 disrupts the alignment between the t-tubule and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), uncoupling the DHPR and RyR1. D. Altering the interaction between JFP-45 and the DHPR results in a misalignment of the DHPR and RyR1. The figure depicts the uncoupling as a physical uncoupling but reality the impairment may be a more subtle decrease in the strength of the functional uncoupling.

Skeletal muscle expresses two ubiquitous calpains, m-calpain and μ-calpain and the muscle specific calpain, calpain-3. Calpain-3 and μ-calpain are activated in the physiological Ca2+ concentration range. However, Ca2+-dependent uncoupling was induced in mouse muscle fibers lacking calpain-3 (34) and the calpain inhibitor, calpeptin did not prevent LFF in intact muscle fibers (1). Although in vivo exercise increased m- and μ-calpain activity and in vitro activation of endogenous calpain activity proteolysed RyR1 and an unidentified 88-kDa junctional SR protein, proteolysis of RyR1 did not alter SR Ca2+ flux or SR [3H]ryanodine binding, a sensitive indicator of channel activity (1). Further Ca2+-induced ECC-uncoupling was not associated with an increase in RyR, DPHR or triadin proteolysis. Thus, if calpain-mediated proteolysis is in involved in ECC-uncoupling, the target(s) are unknown.

Phospholipase A2 is a family of 20 distinct phospholipases clustered into multiple groups including: secreted (sPLA2), cytosolic (cPLA2), and Ca2+-independent (iPLA2). Skeletal muscle expresses all three of these types of PLA2s and in vivo exercise significantly increased PLA2 activity (11). PLA2 activation leads to hydrolysis of the fatty acid from the second carbon of the glycerol backbone of phospholipids (sn-2 position) liberating arachidonic acid. The effects of arachidonic acid production are difficult to predict as it can bind a number of ion channels, activate nitric oxide synthase, phosphokinases A and C, and alter membrane fluidity. Further, arachidonic acid is a precursor for the generation of various eicosanoids and related bioactive lipid mediators. In addition, the remaining free fatty acids and lysophospholipids can destabilize membrane lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions (7). Thus, the destabilizing effect of PLA2 products could significantly alter the structural interactions required to maintain the functional integrity of the triad.

Inositol phosphates have also been shown to modulate skeletal muscle ECC. Shen et al (29) demonstrated that the accumulation of phosphatidyl inositol(3,5)phosphate (PidIns(3,5)P2) a component of the SR, activates RyR1 and in excess impairs SOCE. Accumulation of PidIns(3,5)P2 in the SR due to the genetic ablation of a newly identified muscle-specific inositol phosphatase resulted in significantly decreased run time to exhaustion, severe contractile impairment and rapid fatigue in both the soleus and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles.

An increase in intracellular Ca2+ causes protein kinase-C (PKC) to associate with the plasma membrane where it can be activated by diacylglycerol. All of the minor triadic proteins discussed above, with the exception of junctate, have predicted PKC phosphorylation sites, and therefore may be modified upon PKC activation. Phosphorylation can alter protein-protein interactions and could thereby disrupt interactions critical for the maintenance of the triad. However, Ca2+-induced EC-uncoupling is not mediated by protein phosphorylation as the uncoupling occurred in the absence of ATP and protein phosphorylation would likely be reversed during the prolonged time course of LFF.

The role of ROS in skeletal muscle fatigue has recently been reviewed in detail by Reid (28). Both increased mitochondrial Ca2+ and arachidonic acid enhance mitochondrial ROS production which can in turn damage proteins and membranes and reduce muscle performance. However, the role of ROS in LFF is questionable, as the reducing agent DTT did not prevent Ca2+-induced excitation-contraction uncoupling, and neither DTT nor the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine prevented fatigue induced decrease in Ca2+ release in intact fibers (6).

CONCLUSION

An uncoupling of t-tubule excitation from SR Ca2+ release contributes to LFF. It is clear that the interactions between the DHPR and RyR1 are insufficient to maintain the critical coupling between the two channels and that additional components of the triad must contribute. Of the numerous minor triadic proteins, the junctophilins and JFP-45, which span the gap between the SR and t-tubule, and mitsugumin-29, which maintains the conformation of the ttubule, appear to play a critical role in maintaining the architectural integrity of the triad. Thus, modification of these proteins could decrease the efficacy of ECC and may contribute to LFF.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH AG023902) and the American Heart Association (AHA 0160407Z).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen DG, Lamb GD, Westerblad H. Skeletal muscle fatigue: cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:287–332. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson AA, Treves S, Biral D, Betto R, Sandonà D, Ronjat M, Zorzato F. The novel skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum JP-45 protein. Molecular cloning, tissue distribution, developmental expression, and interaction with alpha 1.1 subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39987–39992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aracena P, Tang W, Hamilton SL, Hidalgo C. Effects of S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosylation on calmodulin binding to triads and FKBP12 binding to type 1 calcium release channels. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:870–881. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balog EM, Norton LE, Bloomquist RA, Cornea RL, Black DJ, Louis CF, Thomas DD, Fruen BR. Calmodulin oxidation and methionine to glutamine substitutions reveal methionine residues critical for functional interaction with ryanodine receptor-1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15615–15621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannister RA. Bridging the myoplasmic gap: recent developments in skeletal muscle excitation-contraction coupling. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2007;28:275–283. doi: 10.1007/s10974-007-9118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruton JD, Place N, Yamada T, Silva JP, Andrade FH, Dahlstedt AJ, Zhang SJ, Katz A, Larsson NG, Westerblad H. Reactive oxygen species and fatigue-induced prolonged low-frequency force depression in skeletal muscle fibres of rats, mice and SOD2 overexpressing mice. J Physiol. 2008;586:175–184. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke JE, Dennis EA. Phospholipase A2 structure/function, mechanism, and signaling. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:S237–S242. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800033-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corona BT, Balog EM, Doyle JA, Rupp JC, Luke RC, Ingalls CP. Junctophilin damage contributes to early strength deficits and EC coupling failure after eccentric contractions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C365–376. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00365.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delbono O, Xia J, Treves S, Wang ZM, Jimenez-Moreno R, Payne AM, Messi ML, Briguet A, Schaerer F, Nishi M, Takeshima H, Zorzato F. Loss of skeletal muscle strength by ablation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum protein JP45. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20108–20113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707389104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dirksen RT. Checking your SOCC and feet: the molecular mechanisms of Ca2+ entry in skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2009;587:3139–3147. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.172148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federspil G, Baggio B, De Palo C, De Carlo E, Borsatti A, Vettor R. Effect of prolonged physical exercise on muscular phospholipase A2 activity in rats. Diabete Metab. 1987;13:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng W, Tu J, Yang T, Vernon PS, Allen PD, Worley PF, Pessah IN. Homer regulates gain of ryanodine receptor type 1 channel complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44722–44730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fill M, Copello JA. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:893–922. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill CA, Thompson MW, Ruell PA, Thom JM, White MJ. Sarcoplasmic reticulum function and muscle contractile character following fatiguing exercise in humans. J Physiol. 2001;531:871–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0871h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirata Y, Brotto M, Weisleder N, Chu Y, Lin P, Zhao X, Thornton A, Komazaki S, Takeshima H, Ma J, Pan Z. Uncoupling store-operated Ca2+ entry and altered Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum through silencing of junctophilin genes. Biophys J. 2006;90:4418–4427. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.076570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito K, Komazaki S, Sasamoto K, Yoshida M, Nishi M, Kitamura K, Takeshima H. Deficiency of triad junction and contraction in mutant skeletal muscle lacking junctophilin type 1. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:1059–1067. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komazaki S, Ito K, Takeshima H, Nakamura H. Deficiency of triad formation in developing skeletal muscle cells lacking junctophilin type 1. FEBS Lett. 2002;524:225–229. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramerova I, Kudryashova E, Wu B, Ottenheijm C, Granzier H, Spencer MJ. Novel role of calpain-3 in the triad-associated protein complex regulating calcium release in skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3271–3280. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Launikonis BS, Stephenson DG, Friedrich O. Rapid Ca2+ flux through the transverse tubular membrane, activated by individual action potentials in mammalian skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2009;587:2299–2312. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.168682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marty I, Fauré J, Fourest-Lieuvin A, Vassilopoulos S, Oddoux S, Brocard J. Triadin: what possible function 20 years later? J Physiol. 2009;587:3117–3121. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melzer W, Herrmann-Frank A, Lüttgau HC. The role of Ca2+ ions in excitation-contraction coupling of skeletal muscle fibres. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1241:59–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(94)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng X, Wang G, Viero C, Wang Q, Mi W, Su XD, Wagenknecht T, Williams AJ, Liu Z, Yin CC. CLIC2-RyR1 interaction and structural characterization by cryo-electron microscopy. J Mol Biol. 2009;387:320–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishi M, Komazaki S, Kurebayashi N, Ogawa Y, Noda T, Iino M, Takeshima H. Abnormal features in skeletal muscle from mice lacking mitsugumin29. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1473–1480. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oddoux S, Brocard J, Schweitzer A, Szentesi P, Giannesini B, Brocard J, Fauré J, Pernet-Gallay K, Bendahan D, Lunardi J, Csernoch L, Marty I. Triadin deletion induces impaired skeletal muscle function. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34918–34929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan Z, Yang D, Nagaraj RY, Nosek TA, Nishi M, Takeshima H, Cheng H, Ma J. Dysfunction of store-operated calcium channel in muscle cells lacking mg29. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:379–383. doi: 10.1038/ncb788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polkey MI, Moxham J. Clinical aspects of respiratory muscle dysfunction in the critically ill. Chest. 2001;119:926–939. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.3.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prosser BL, Hernández-Ochoa EO, Zimmer DB, Schneider MF. Simultaneous recording of intramembrane charge movement components and calcium release in wild-type and S100A1-/- muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2009;587:4543–4559. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.177246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reid MB. Free radicals and muscle fatigue: Of ROS, canaries, and the IOC. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen J, Yu WM, Brotto M, Scherman JA, Guo C, Stoddard C, Nosek TM, Valdivia HH, Qu CK. Deficiency of MIP/MTMR14 phosphatase induces a muscle disorder by disrupting Ca2+ homeostasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:769–776. doi: 10.1038/ncb1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen X, Franzini-Armstrong C, Lopez JR, Jones LR, Kobayashi YM, Wang Y, Kerrick WG, Caswell AH, Potter JD, Miller T, Allen PD, Perez CF. Triadins modulate intracellular Ca(2+) homeostasis but are not essential for excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37864–37874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stiber JA, Zhang ZS, Burch J, Eu JP, Zhang S, Truskey GA, Seth M, Yamaguchi N, Meissner G, Shah R, Worley PF, Williams RS, Rosenberg PB. Mice lacking Homer 1 exhibit a skeletal myopathy characterized by abnormal transient receptor potential channel activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2637–2647. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01601-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Treves S, Scutari E, Robert M, Groh S, Ottolia M, Prestipino G, Ronjat M, Zorzato F. Interaction of S100A1 with the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) of skeletal muscle. Biochem. 1997;36:11496–11503. doi: 10.1021/bi970160w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Treves S, Vukcevic M, Maj M, Thurnheer R, Mosca B, Zorzato F. Minor sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane components that modulate excitation-contraction coupling in striated muscles. J Physiol. 2009;587:3071–3079. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verburg E, Murphy RM, Richard I, Lamb GD. Involvement of calpains in Ca2+-induced disruption of excitation-contraction coupling in mammalian skeletal muscle fibers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C1115–1122. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00008.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yazawa M, Ferrante C, Feng J, Mio K, Ogura T, Zhang M, Lin PH, Pan Z, Komazaki S, Kato K, Nishi M, Zhao X, Weisleder N, Sato C, Ma J, Takeshima H. TRIC channels are essential for Ca2+ handling in intracellular stores. Nature. 2007;448:78–82. doi: 10.1038/nature05928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]