Abstract

We experienced a case of primary pulmonary biphasic synovial sarcoma, which was confirmed by immunohistochemistry and molecular testing of SYT-SSX2 fusion transcripts. The patient was a 61-year-old man who presented with a well-defined mass in the left upper lung field on chest radiography. Left upper lobectomy with lymph node dissection was performed. Histological and immunophenotypic features were consistent with biphasic synovial sarcoma. Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, performed using RNA extracted from frozen tumor samples for the detection of SYT-SSX fusion gene, amplified a single 331-bp fragment that was characteristic of the SYT-SSX2 fusion transcripts. We report a case of primary pulmonary biphasic synovial sarcoma, which was confirmed by SYT-SSX2 fusion transcripts, and present a brief review of the literature on Korean cases.

Keywords: Sarcoma, synovial; Lung neoplasms; Gene fusion

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary sarcoma usually occurs through metastasis from other locations such as the extremities, and primary pulmonary sarcoma accounts for < 0.5% of all pulmonary malignancies [1]. Cytogenetic studies have detected the chromosomal translocation t (x;18) (p11;q11) in synovial sarcoma and have determined that the translocation fuses the SYT gene from chromosome 18 with the SSX1 and SSX2 genes on chromosome X to form SYT-SSX1 or SYT-SSX2, which is thought to function as an aberrant transcriptional regulator [1-3]. The fusion genes detected by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) have been used to make a definitive diagnosis of synovial sarcoma [3], and it has been reported that they are related to the histological characteristics and prognosis of this tumor. It has also been demonstrated that patients with the SYT-SSX2 fusion transcripts have a better prognosis than those with SYT-SSXI fusion transcripts [2].

Only a few reports have examined primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in Korea. Here, we report a case of primary pulmonary biphasic synovial sarcoma that was confirmed by detection of an SYT-SSX2 fusion gene, and present a brief review of the literature concerning this form of tumor in Korean patients.

CASE REPORT

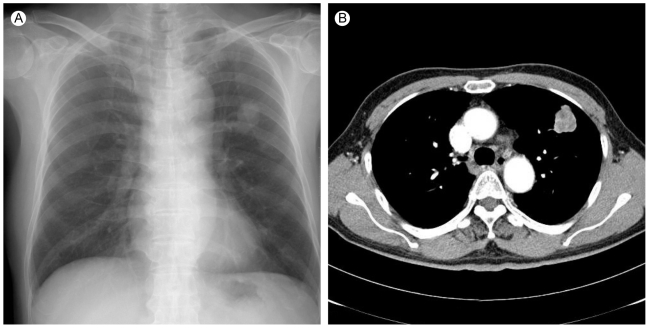

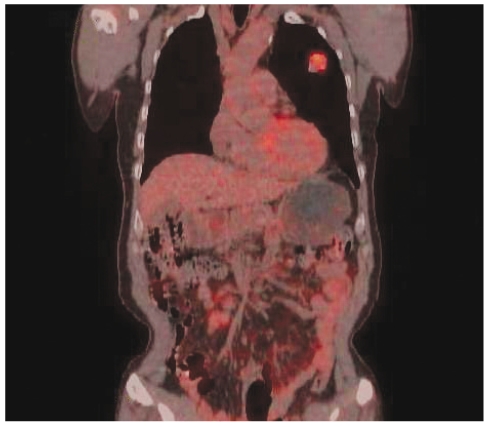

A 61-year-old man presented with an incidentally found mass in the lung, which was detected by a health-screening program. He had a smoking history of 30 pack-years. On admission, his vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 120/80 mmHg; pulse rate, 75/min; respiration rate, 20/min; and body temperature, 36.5℃. He was not chronically ill, and he had clear consciousness. Chest auscultation revealed no abnormal heart and lung sounds. No enlarged lymph nodes were found in the head, neck, or extremities. Simple chest X-ray revealed a well-defined round mass in the left upper lung field (Fig. 1A). Computed tomography (CT) of the chest showed a 3 × 3-cm, well-defined, lobulated round mass in the anterior segment of the left upper lobe, and on contrast images, the mass showed heterogeneous enhancement with ≥ 20 HU difference in enhancement (Fig. 1B). Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT showed a pulmonary mass at the same site with an increased F18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) standardized uptake value (SUV) of 8.1. No increase in the FDG uptake rate in the lymph nodes was detected at the mediastinum and both pulmonary hila (Fig. 2). Radioisotope bone scans revealed no abnormal findings. Peripheral blood tests showed white blood cells, 7,770/mm3; hemoglobin, 13.4 g/dL; and platelets 258,000/mm3. No abnormal findings were observed in routine chemistry tests, serum electrolytes, blood coagulation tests, and urinalysis.

Figure 1.

(A) Chest radiograph shows a left upper lobe mass. (B) On chest CT scan, a 3 × 3-cm lobulated, heterogeneous enhancing mass was noted in the anterior segment of the left upper lobe.

Figure 2.

F18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) fused coronal image; fusion PET demonstrates a moderately hypermetabolic mass in the left upper lobe.

Light microscopic examination of the specimens obtained through percutaneous lung biopsy revealed a spindle-cell-type neoplastic hyperplasia and localized areas of epithelial cells around the spindle cells. Immunohistochemistry displayed positive reactivity for Bcl-2, CD99, and β-catenin, with a strong possibility of a solitary fibrous tumor. However, a definite diagnosis could not be made because the tumor was negative for CD34, for which most solitary fibrous tumors are positive.

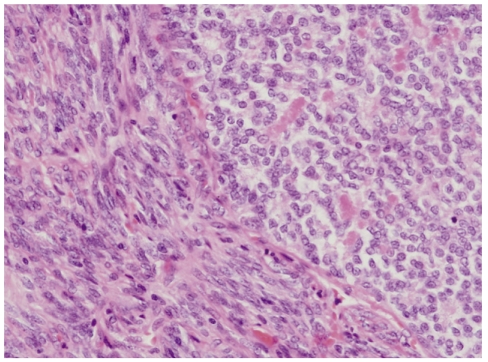

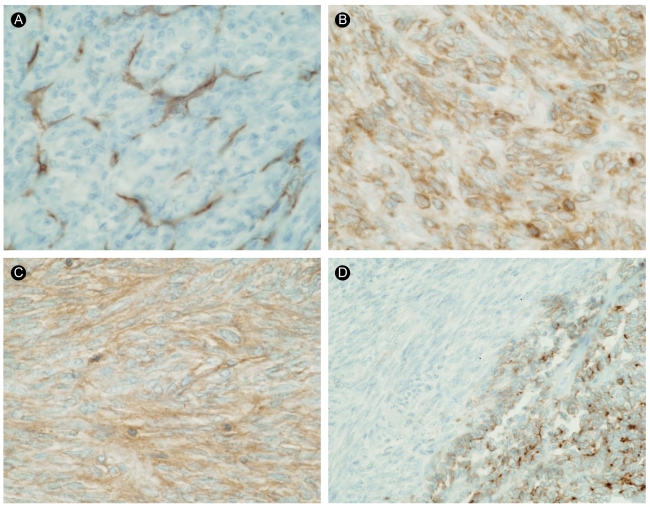

Left upper lobe resection with lymph node dissection was performed, and a 3.8 × 2.8 × 25-cm, well-defined, whitish-yellow, smooth-surfaced oval mass was found. Light microscopic examination of the surgical specimen showed spindle cells and focal epithelial cells with mitotic activity of 10/10 HPFs (Fig. 3). By immunohistochemistry, the epithelial cells were positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), whereas the spindle cells were negative. In addition, the tumor was positive for S-100, CD99, and Bcl-2, but negative for CD34, desmin, cytokeratin pan (CKpan), thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), surfactant protein A (SP-A), leading to a diagnosis of primary pulmonary biphasic synovial sarcoma (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Light microscopy shows spindle cells with focal epithelial differentiation (H&E, ×400).

Figure 4.

The results of immunohistochemical staining for CD34 (A), Bcl-2 (B), CD99 (C), and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (D, ×400). The tumor cells were completely negative for CD34 and focally positive for Bcl-2. The malignant epithelial cells were positive for EMA, but the spindle cells were negative for EMA.

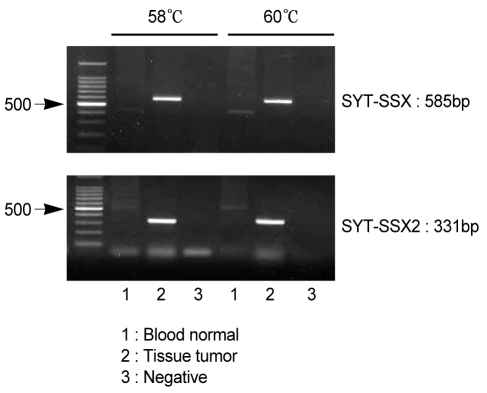

RT-PCR was performed according to the method of Kawai et al. [2]. Total RNA was isolated from the frozen sections obtained from the tumor tissue using the acid/guanidinum/phenol/chloroform method, and 1 µg RNA was transcribed using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (GIBCO, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and random hexamers. The cDNA was amplified using the forward primer (5'CAACAGCAAGATGCATACCA3') and reverse primer (5'CACTTGCTATGCACCTGATG3' for SSX; 5'GGTGCAGTTGTTTCCCATCG3' for SSX1; or 5'GGCACAGCTCTTTCCCATCA3' for SSX2). RT-PCR was carried out under the following conditions: 35 amplification cycles, each consisting of denaturation at 95℃ for 1 minute, annealing at 58℃ or 60℃ for 1 minute, and extension at 72℃ for 1 minute, followed by 10 minutes of an additional extension step at 72℃. The PCR products were then electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and subsequently identified as an SYT-SSX (585 bp) or SYT-SSX2 (331 bp) gene (Fig. 5). Chest radiographs taken at 16 months after surgery showed pleural effusion on the left side. Chest CT revealed a left pleura-based mass, enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, and suspected malignant hydrothorax. PET-CT scans showed a left pleural mass with an increased F18-FDG SUV of 6.5. A percutaneous lung biopsy was performed to make a definitive diagnosis of the left pleura-based mass. Light microscopy and immunohistochemistry confirmed the recurrence of synovial sarcoma. The patient was scheduled for total resection of the tumor along with adjacent chemoradiotherapy.

Figure 5.

Analysis of SYT-SSX fusion transcripts in synovial sarcoma. Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of total RNA from a patient with synovial sarcoma was performed using the SYT-SSX (consensus), SSX1, and SSX2 primers. The PCR products were then isolated by electrophoresis on an agarose gel. The size of the SYT-SSX product was 585 bp, and that of the SYT-SSX2 product was 331 bp.

DISCUSSION

Synovial sarcoma can be histopathologically divided into biphasic, monosphasic fibrous, monophasic epithelial, and poorly differentiated types. In cases of the biphasic type, both epithelial and spindle cells are present; therefore, the diagnosis is relatively easy to make. However, in cases of the monophasic type, which has homogeneous patterns of spindle cells, immunohistochemical staining is needed to distinguish this tumor from other spindle-cell-type tumors such as fibrosarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, leiomyosarcoma, and spindle cell carcinoma [1]. Coindre et al. [3] have suggested that the most reliable findings are positivity for EMA or cytokeratins AE1/AE3 and negativity for CD34. However, Begueret et al. [4] have reported that this tumor can be positive for the S-100 protein, α-smooth muscle actin, c-kit, CD34, and calretinin. Based on these results, it is conceivable that immunohistochemistry is not the most accurate test for synovial sarcoma. In our case, the tumor mass was negative for CD34, which distinguished this tumor from fibrosar-coma. EMA-negative spindle cells were observed, in contrast to EMA-positive epithelial cells. Based on these findings, our case was diagnosed as a biphasic synovial sarcoma.

Recently, through cytogenetic studies, the translocation of specific genes has been identified in various synovial-sarcoma-like forms of sarcoma. The chromosomal translocation t (x;18) (p11;q11) has been found in 95% of synovial sarcomas in which the SYT gene located on the long arm of chromosome 18 is fused with the SSX1 or SSX2 gene located on the short arm of chromosome X, forming a new SYT-SSX1 or SYT-SSX2 fusion gene. The SYT-SSX fusion gene induces the development of sarcoma. Although the biological role of the fusion gene has yet to be identified, it has been reported that the SYT protein functions as a transcriptional regulator, and the SSX protein functions as a complement for the transcriptional inhibitor [1]. The SYT-SSX1 fusion gene has been found in the majority of biphasic synovial sarcomas, whereas the SYT-SSX2 fusion gene has been detected in the majority of monophasic synovial sarcomas [2]. Nevertheless, Ladanyi et al. [5] have reported that histological classification does not always coincide with the fusion-gene classification. In our case of biphasic synovial sarcoma, an SYT-SSX2 gene was detected. The detection of fusion genes has been reported to have a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 100% for the diagnosis of synovial sarcoma [6], which has made this technique a widely used and important method for establishing a definite diagnosis of this tumor.

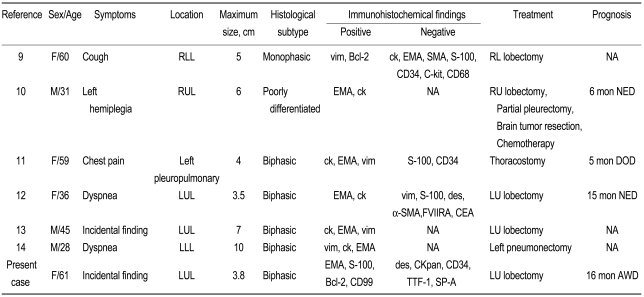

A total of six cases of primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma have been reported in Korea (Table 1) [7-12]. Our case is the first that confirmed the presence of an SYT-SSX fusion gene. Previous cases in Korea have occurred in patients aged 28 to 61 years (mean, 45.7 years), and four occurred in women. No specific symptoms were found in two cases. The tumor size was 3.5 to 10 cm (mean, 5.6 cm). The tumor developed in the left lung in five cases. As for the histological classification, five were biphasic type, one was monophasic type, and another was poorly differentiated type. The epithelial cells were positive for EMA or cytokeratin and negative for CD34. At the initial diagnosis, pneumonectomy was performed in all cases, except a case with accompanying pleural invasion and malignant pleural effusion. According to the report by Begueret et al. [4], many cases of synovial sarcoma are mistakenly diagnosed as spindle-cell tumors such as fibrosarcoma or hemangiopericytoma because of the absence of methods that give a definite diagnosis of synovial sarcoma. Recently, cases of synovial sarcoma have increased due to the aforementioned diagnostic tool. The detection of the fusion gene will assist in making a definite diagnosis of synovial sarcoma.

Table 1.

Clinical features of primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma in Korea

RLL, right lower lobe; vim, vimentin; ck, cytokeratin; EMA, epithelial membrane antigen; SMA, smooth muscle antigen; NA, not available; RUL, right upper lobe; NED, no evidence of disease; DOD, died of disease; LUL, left upper lobe; des, desmin; FVIIRA, factor VII related antigen; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; LLL, left lower lobe; TTF-1, thyroid transcription factor-1; AWD, alive with disease.

Several reports have examined the relationship between the SYT-SSX fusion gene and the prognosis of synovial sarcoma. Although some investigators have indicated that patients with SYT-SSX1 fusion genes have a poorer prognosis than do those with SYT-SSX2 fusion genes, Guillou et al. [6] have reported contradictory results. Further studies with a larger number of cases are needed to verify the relationship between the patterns of fusion genes and the prognosis of synovial sarcoma.

We have reported a case that was definitively diagnosed as primary pulmonary biphasic sarcoma based on the detection of an SYT-SSX2 fusion gene.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Hosono T, Hironaka M, Kobayashi A, et al. Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma confirmed by molecular detection of SYT-SSX1 fusion gene transcripts: a case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:274–279. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawai A, Woodruff J, Healey JH, Brennan MF, Antonescu CR, Ladanyi M. SYT-SSX gene fusion as a determinant of morphology and prognosis in synovial sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:153–160. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coindre JM, Pelmus M, Hostein I, Lussan C, Bui BN, Guillou L. Should molecular testing be required for diagnosing synovial sarcoma? A prospective study of 204 cases. Cancer. 2003;98:2700–2707. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begueret H, Galateau-Salle F, Guillou L, et al. Primary intrathoracic synovial sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 40 t(X;18)-positive cases from the French Sarcoma Group and the Mesopath Group. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:339–346. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000147401.95391.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladanyi M, Antonescu CR, Leung DH, et al. Impact of SYT-SSX fusion type on the clinical behavior of synovial sarcoma: a multi-institutional retrospective study of 243 patients. Cancer Res. 2002;62:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillou L, Benhattar J, Bonichon F, et al. Histologic grade, but not SYT-SSX fusion type, is an important prognostic factor in patients with synovial sarcoma: a multicenter, retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4040–4050. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee EA, Lee DY, Kwag HJ, et al. A case of monophasic fibrous synovial sarcoma confirmed primary pulmonary origin by 18F-FDG PET/CT. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2006;60:673–677. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin SH, Song DS, Jung WS, et al. Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma with brain metastasis. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;33:329–332. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song SH, Lee KH, Oh JH, et al. A case of primary pulmonary sarcoma with morphologic features of biphasic synovial sarcoma. Tuberc Respir Dis. 1998;45:1284–1289. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon GS, Park SY, Kang GH, Kim OJ. Primary pulmonary sarcoma with morphologic features of biphasic synovial sarcoma: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 1998;13:71–76. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1998.13.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim MH, Kim KT, Kim HJ. Primary pulmonary synovial sarcoma: a case report. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;30:1259–1261. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin JS, Hwang JJ, Choi YH, Kim HJ. Intrapulmonary synovial sarcoma: a case report. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;26:726–729. [Google Scholar]