Abstract

Objectives

To assess pharmacy students' attitudes toward death and end-of-life care.

Methods

Third-year pharmacy students enrolled in the Ethics in Christianity and Health Care course were administered a survey instrument prior to introduction of the topic of end-of-life care. Students' attitudes toward different professions' roles in end-of-life care and their comfort in discussing end-of-life issues were assessed. The survey instrument was readministered to the same students at the end of their fourth year.

Results

On most survey items, female students responded more favorably toward death and end-of-life care than male students. One exception was the perceived emotional ability to be in the room of a dying patient or loved one. Post-experiential survey responses were generally more favorable toward death and end-of-life care than were pre-discussion responses.

Conclusions

In general, when surveyed concerning death and end-of-life care, female students responded more favorably than male students, and responses at the end of the fourth year were more favorable than at the beginning of the course.

Keywords: end-of-life care, death, pharmacy students, attitudes

INTRODUCTION

The topic of death and end-of-life care is profound. Even though death has always been the ultimate consequence of life, the public conversation about this subject has occurred more frequently only in the last 40 years following the groundbreaking work in 1969 by Kubler-Ross entitled On Death and Dying.1 The continued need for this discussion produced the journal Death Studies, which published its first issue in 1977.

The medical community has dealt with death and dying much more commonly than the average person, yet the discussion of this topic has evolved fairly slowly, even in health professions' training.2-14 Health care professionals are often on the front lines of death and dying, but may be ill-prepared by their professional education to help in these situations. Numerous studies have been performed surveying various medical, nursing, and pharmacy colleges to determine the amount of time and attention that end-of-life care education receives in their respective curricula.2-12 As would be expected, those studies report an overall increased focus on end-of-life care education in US medical schools; however, little longitudinal research has been performed in other health professions' schools.3,6-9,11 Two studies conducted in 1985 investigated the status of death education in US colleges and schools of pharmacy as well as student involvement and instructor background.4,5 One study described survey results involving pharmacy, nursing, and medical schools;4 the other study compared those survey results with the results of the same survey involving other health professional schools.5 Sixty-eight percent of colleges and schools of pharmacy offered some type of death education, while 96% of medical schools and 95% of nursing schools offered death education in their curricula.4 In 2001, another survey of colleges and schools of pharmacy explored both didactic and experiential death education as well as instructional methods and faculty with a focus on end-of-life care. In this study, 62% of institutions reported didactic teaching in end-of-life care, and 58% of institutions reported experiential teaching in end-of-life care.10

The importance of discussing death and dying in colleges and schools of pharmacy may not be obvious, yet more patients are choosing to die at home and are more likely to receive outpatient treatment. Also, the newer arenas in which to practice pharmacy increases the likelihood that these practitioners will experience the death of patients.4 The significance of this topic has also been recognized by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree, which suggests that principles of end-of-life care and concepts of palliative care should be part of the pharmacotherapy foundation.15 Furthermore, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) has identified 6 areas in which to eliminate harm, waste, and disparities as part of their National Priorities Partnership;16 1 of the 6 areas is that of palliative and end-of-life care. ASHP explains that the role of the pharmacist in this field includes promoting communication, assisting with emotional support, providing education, facilitating access to needed pain medications, and avoiding adverse drug events.17

Although there have been inquiries that explore curricula focused on end-of-life care, to our knowledge there have been no studies that address pharmacy students' attitudes toward death and end-of-life care. With pharmacists becoming more involved in patient care, the purpose of this paper was to describe pharmacy students' attitudes toward death and end-of-life care.

DESIGN

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to conducting this study. The pharmacy students' attitudes toward death and end-of-life care survey instrument was constructed and administered to third-year pharmacy students enrolled in the required Ethics in Christianity and Health Care course in March 2008 prior to beginning the 2-week topic of end-of-life care and death (ie, pre-discussion survey). This portion of the course included the following: (1) discussing advance directives and living wills in relation to the Karen Ann Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Terri Schiavo cases; (2) providing each student with a living will for personal use and reviewing this document with the class; (3) talking briefly about assisted suicide and euthanasia; (4) discussing Oregon's Death with Dignity (5) having 2 guest speakers demonstrate and discuss music therapy in end-of-life care; and (6) watching 2 videos and having the students write their reflections as they viewed them. The videos addressed several experiences of patients and their families making decisions about end-of-life issues. Whose Death Is It, Anyway? (Choice in Dying, Inc. New York, NY, 1996) involved an audience discussion of 5 situations of patients related to death and dying, and A Time to Change from a Bill Moyers special aired on the Public Broadcasting System discussing the Balm of Gilead inpatient unit in Birmingham, Alabama, and the complex physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and financial aspects of end-of-life care. The course ended in May 2008, and students started their advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) in June 2008. This survey instrument was given subsequently to the same group of students in May 2009 at the end of their fourth year during graduation week (ie, post-experiential).

The survey items were constructed by the authors and developed to assess the course topics and objectives concerning end-of-life care as well as students' thoughts as they approached being more involved in patient care. The rationale behind the design of the survey items was to explore students' professional and personal attitudes toward the various aspects of death and end-of-life care. The instrument was divided into 2 sections: the first section evaluated demographics of the survey respondents, including gender, age, educational background, and their experiences with the death of someone close to them; the second section included 23 items using a 5-point Likert scale to assess students' attitudes toward issues such as the role of various health professions in end-of-life aspects, their comfort in discussing end-of-life issues with various groups of people, and the perceived role of a pharmacist in end-of-life care. Two other pharmacy faculty members reviewed the survey draft and provided input before it was finalized. The survey instrument ensured students' anonymity, and participation was voluntary.

The study incorporated 2 hypotheses: (1) there would be no difference between female and male students' attitudes about end-of-life care; (2) the post-experiential survey responses would be more favorable regarding end-of-life care than the pre-discussion survey responses. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and the alpha value was set at 0.05. Items 8 and 20 were negatively worded in the survey instrument and these items were reverse coded in the analysis to address the instrument's psychometric properties.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

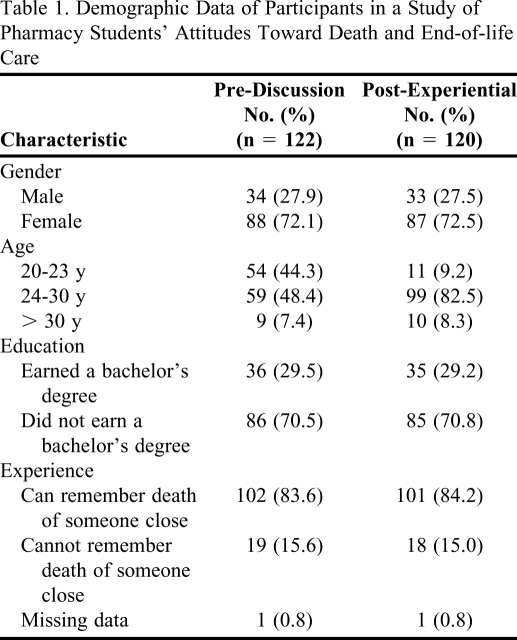

Of 124 students enrolled in the course, 122 students completed the pre-discussion survey instrument (98.4%), and 120 students completed the post-experiential survey instrument (96.8%). Four missing data points were evident in the pre-discussion and post-experiential responses, and no numbers were substituted in their place. The demographic data for the survey participants are presented in Table 1. Although ethnicity information was not requested on the instrument, approximately 94% of the students in this cohort were white, 4% were African American, 1% were Asian, and 1% were Native American.

Table 1.

Demographic Data of Participants in a Study of Pharmacy Students' Attitudes Toward Death and End-of-life Care

Instrument Psychometrics

Factor analysis was employed using principal component analysis and the varimax rotation method on the post-experiential survey results. The best solution that emerged from the data yielded 4 factors that resulted in 55.8% explained variance. The guideline for item grouping on only 1 factor was a loading of ≥ 0.40, and all of the items loaded on only 1 factor based on this criterion. The reliability of the 23 Likert-scale items yielded a Cronbach's alpha of 0.88. The factors, their associated items, and their corresponding Cronbach's alpha results were as follows:

Factor 1 (Interacting With and Knowledge of the Dying); Items 9-11, 8-19, 21-23; alpha of 0.77;

Factor 2 (Personal Thoughts and Conversations); Items 12-17; alpha of 0.87;

Factor 3 (Comfort in Discussing End-of-life Issues); Items 4-8, 20; alpha of 0.75; and,

Factor 4 (Addressing Death Issues in Health Professions' Curricula); Items 1-3; alpha of 0.79.

Item-to-total correlations on the post-experiential responses ranged from 0.24 (Item 1) to 0.69 (Item 5), and the item-to-total correlations on all 23 items were significant at the p < 0.01 level. Overall, the survey items loaded logically on these 4 factors, and the psychometric analysis yielded sound results.

Hypothesis 1

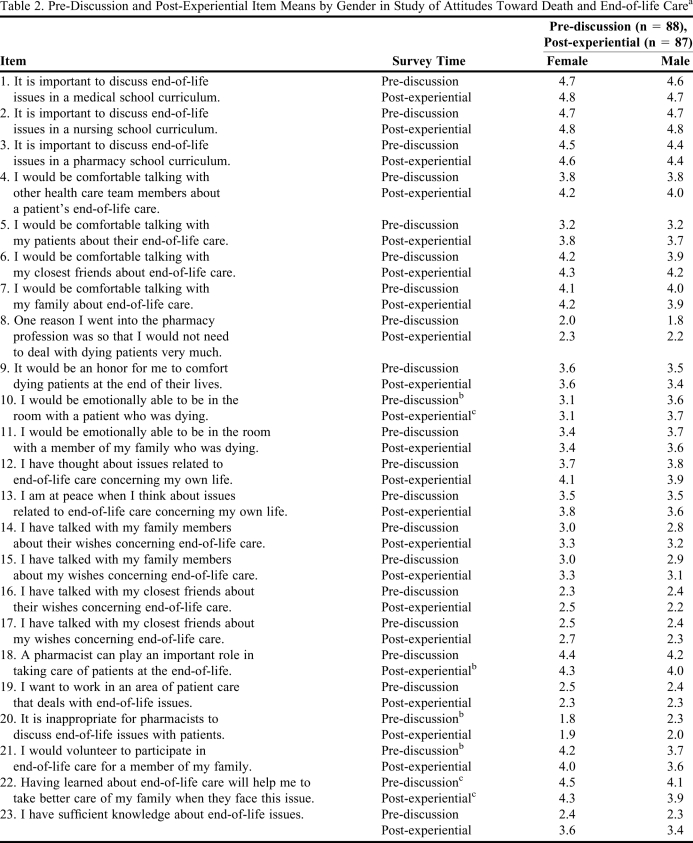

The first hypothesis of this study was that there would be no differences between male and female students' attitudes toward end-of-life care. On the majority of items, female students' responses were more favorable toward death and end-of-life care than those of male students (Table 2). The exceptions to this involved being emotionally able to be in the room of a dying patient (Item 10), or a dying member of their family (Item 11); for both of these items, male students perceived more favorably their emotional ability to be present in the room. Concerning Item 10, male students responded more favorably than female students in both the pre-discussion and post-experiential survey instruments (p < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively). Also concerning this item, the mean remained the same for female students on both the pre-discussion and post-experiential survey instruments, yet the mean increased for male students in the post-experiential survey instrument. In summary, evidence existed to refute the first hypothesis that there were no significant differences between female and male students toward death and end-of-life care.

Table 2.

Pre-Discussion and Post-Experiential Item Means by Gender in Study of Attitudes Toward Death and End-of-life Carea

Responses are based on the Likert-type scale of 5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = neutral, 2 = disagree, 1 = strongly disagree.

bp < 0.05

cp < 0.01

Hypothesis 2

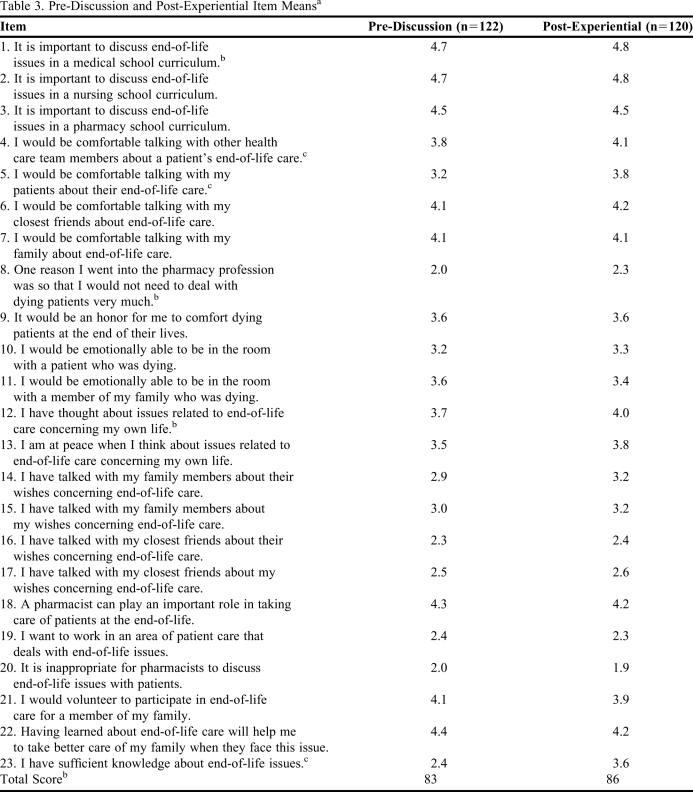

The second hypothesis was that the post-experiential survey responses would be more favorable than those in the pre-discussion survey instrument. In general, for the majority of the items, as shown in Table 3, the post-experiential responses were more favorable than the pre-discussion responses; specifically, the post-experiential mean scores were higher than the pre-discussion mean scores on 15 of the 23 items (65.2%). Not surprisingly, the subsequent post-experiential mean total score of 86 was significantly higher than that of the pre-discussion mean total score of 83 (p < 0.05). Significant differences were seen in Items 1, 4, 5, 8, 12, and 23, with students responding more favorably in the post-experiential survey instrument than in the pre-discussion survey instrument. The greatest differences involved perceived comfort in talking with other members of the health care team and their patients (Items 4 and 5, respectively), and having sufficient knowledge about end-of-life issues (Item 23) (p < 0.01 for all 3 items). In summary, evidence existed supporting the second hypothesis that the post-experiential responses would be more favorable than the pre-discussion responses.

Table 3.

Pre-Discussion and Post-Experiential Item Meansa

Responses are based on the Likert-type scale of 5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = neutral, 2 = disagree, 1 = strongly disagree.

bp < 0.05

cp < 0.01

DISCUSSION

Hypothesis 1

The results concerning the differences between the responses of male and female students were interesting. Edward O. Wilson, a well-known sociobiologist, has said that females tend to score higher in empathy, verbal, and social skills, while men tend to score higher in independence, dominance, spatial, and mathematical skills.18 Carol Gilligan also believed that women tend to think more in terms of care while men gravitate more toward areas of justice.19 Therefore, possible reasons for the differences in this study follow the premise that women are generally more care-oriented and verbal than men.

Conversely, it was intriguing that the male students' responses were more favorable than those of female students on both pre-discussion and post-experiential survey instruments about their perceived emotional ability to be in a room with a patient or family member who was dying (Items 10 and 11). Male adults generally have a reputation of being able to cope with death and dying issues more easily than female adults; thus, this could explain their more favorable thoughts of being in close proximity to a dying person. Female students perceived more of a role for themselves, both personally and professionally, in end-of-life care; male students were more able to be present physically. This could be explained by the connotation of female students perceiving an action to perform (ie, more active involvement) compared with male students just being present in the room of a dying person and allowing this to have an emotional impact on them (ie, more passive involvement).

Hypothesis 2

The differences in pre-discussion and post-experiential mean item and total scores suggested that the course's content about death and end-of-life care had a positive impact on the students' thoughts about these issues. One consideration, however, is that students also had their APPEs between the pre-discussion and post-experiential survey instruments; therefore, it is inappropriate to infer that the course was solely responsible for these changes in responses. Nevertheless, it was encouraging to see that students gave more favorable post-experiential responses concerning their perceived comfort in talking with other members of the health care team (Item 4) and with their patients about end-of-life care (Item 5). Also, the survey instrument did not capture any professional experiences with death that may have occurred specifically during the students' APPEs; only the death of someone close to them was addressed, and this number did not increase from the pre-discussion to the post-experiential survey results. There may have been students who would have answered “yes” to this question in the post-experiential survey instrument concerning a patient with whom they had formed an emotional connection. Therefore, the pre-discussion responses may have been slightly more theoretical in nature while the post-experiential responses may have reflected more actual situations. Regardless, when taking both the course and the APPEs into account, the post-experiential responses for the students' belief that they had sufficient knowledge about end-of-life issues were more favorable than the pre-discussion responses.

Conversely, it was intriguing that Items 8, 9, 11, 18, 19, 21, and 22 (all of which addressed interacting with and knowledge about dying people) had more favorable pre-discussion responses than post-experiential responses. From a professional standpoint, dealing with patients (Items 8, 9, 18, and 19), and from a personal standpoint, dealing with family members (Items 11, 21, and 22), responses could be related to the videos in which pharmacists were not mentioned as being involved in end-of-life care; or perhaps the videos exposed the students to the understandable emotional challenges of working in end-of-life situations. Also possible is that students had a negative experience with end-of-life care during their APPEs, or that health care professionals who taught them in these settings were not comfortable with end-of-life issues, thus contributing to these responses.

Limitations

There were limitations identified in this study. As previously mentioned, the study did not discern whether changes in responses were due solely to the didactic course, nor did it capture those experiences with the death of a patient who students may have encountered during APPEs. A repeated measures design was not considered to assess students' attitudes at the 3 points of baseline, end of course, and end of professional education at graduation. Also, the survey instrument did not include ethnicity in the demographic section, and, therefore, differences in ethnic groups' responses were not part of this study. However, because the race of the class was almost all white, there would not have been enough students of other races to provide appropriate or meaningful analysis in this area. Last, even though the survey instrument was reviewed by others, a pilot study using the instrument was not conducted to gain initial psychometric information.

SUMMARY

There were gender differences in student attitudes about end-of-life matters, as female students' responses were more favorable than male students' responses on the majority of items. This was evident particularly relating to the need to discuss end-of-life care in health professions' curricula, their comfort in talking about end-of-life care, and their perceived knowledge of end-of-life issues that would help them take better care of their own families when these situations arose. Male students' responses were more favorable than those of female students in areas pertaining to being more emotionally able to be in the room of a patient or family member who was dying. For two-thirds of the surveyed items, the post-experiential responses were more favorable than the pre-discussion responses. These results supported the premise that the end-of-life content discussed in the Ethics in Christianity and Health Care Course, as well as possible experiences during these students' APPEs, had a generally favorable impact on their thoughts about end-of-life care. This study also points to the need for continued inclusion of end-of-life care in curricula as well as the need to educate students on the pharmacist's role in palliative and end-of-life care. Further research is needed to explore specific ways in which information about end-of-life can be presented in didactic courses and applied in experiential components of the curriculum.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kubler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. New York, NY: MacMillan Company; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thrush JC, Paulus GS, Thrush PI. The availability of education on death and dying: a survey of US nursing schools. Death Educ. 1979;3(2):131–142. doi: 10.1080/07481187908252946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MD, McSweeney M, Katz BM. Characteristics of death education curricula in American medical schools. J Med Educ. 1980;55(10):844–850. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198010000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickinson GE, Sumner ED, Durand RP. Death education in US professional colleges: medical, nursing, and pharmacy. Death Stud. 1987;11(1):57–61. doi: 10.1080/07481188708252174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickinson GE, Sumner ED, Frederick LM. Death education in selected health professions. Death Stud. 1992;16(3):281–289. doi: 10.1080/07481189208252575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickinson GE, Mermann AC. Death education in US medical schools, 1975-1995. Acad Med. 1996;71(12):1348–1349. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199612000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field D, Wee B. Preparation for palliative care: teaching about death, dying and bereavement in UK medical schools 2000-2001. Med Educ. 2002;36(6):561–567. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickinson GE. A quarter century of end-of-life issues in US medical schools. Death Stud. 2002;26(8):635–646. doi: 10.1080/07481180290088347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickinson GE, Field D. Teaching end-of-life issues: current status in United Kingdom and United States medical schools. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2002;19(3):181–186. doi: 10.1177/104990910201900309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herndon CM, Jackson K, II, Fike DS, Woods T. End-of-life care education in United States pharmacy schools. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20(5):340–344. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson GE. Teaching end-of-life issues in US medical schools:1975-2005. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006;23(3):197–204. doi: 10.1177/1049909106289066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickinson GE. End-of-life and palliative care issues in medical and nursing schools in the United States. Death Stud. 2007;31(8):713–726. doi: 10.1080/07481180701490602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacLean U. Learning about death. J Med Ethics. 1979;5(2):68–70. doi: 10.1136/jme.5.2.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan AM, Lakoma MD, Block SD. The status of medical education in end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(9):685–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. ACPE accreditation standards and guidelines page. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Web site. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2010.

- 16. ASHP resources supporting the national priorities partnership page. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Web site. http://www.ashp.org/Import/PRACTICEANDPOLICY/PracticeResourceCenters/QualityImprovementInitiativeQII/NPP.aspx. Accessed May 26, 2010.

- 17. Palliative and end-of-life care page. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Web site. http://www.ashp.org/Import/PRACTICEANDPOLICY/PracticeResourceCenters/QualityImprovementInitiativeQII/NPP/PalliativeandEOLC.aspx Accessed May 26, 2010.

- 18. Sabbatini, R. Are There Differences Between the Brains of Males and Females? Brain and Mind Electronic Magazine on Neuroscience. Number 11.Oct-Dec 2000. http://www.cerebromente.org.br/n11/mente/eisntein/cerebro-homens.html Accessed July 1, 2010.

- 19.Gilligan C. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]