Abstract

Background

High Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness are frequently implicated in health-risk behaviors, such as smoking and overeating, as well as health outcomes, including mortality. Their associations with physiological markers of morbidity and mortality, such as inflammation, are less well documented. The present research examines the association between the five major dimensions of personality and interleukin-6 (IL-6), a pro-inflammatory cytokine often elevated in patients with chronic morbidity and frailty.

Methods

A population-based sample (N=4,923) from four towns in Sardinia, Italy, had their levels of IL-6 measured and completed a comprehensive personality questionnaire, the NEO-PI-R. Analyses controlled for factors known to have an effect on IL-6: age, sex, smoking, weight, aspirin use, and disease burden.

Results

High Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness were both associated with higher levels of IL-6. The findings remained significant after controlling for the relevant covariates. Similar results were found for C-reactive protein, a related marker of chronic inflammation. Further, smoking and weight partially mediated the association between impulsivity-related traits and higher IL-6 levels. Finally, logistic regressions revealed that participants either in the top 10% of the distribution of Neuroticism or the bottom 10% of Conscientiousness had an approximately 40% greater risk of exceeding clinically-relevant thresholds of IL-6.

Conclusions

Consistent with the literature on personality and self-reported health, individuals high on Neuroticism or low on Conscientiousness show elevated levels of this inflammatory cytokine. Identifying critical medical biomarkers associated with personality may help to elucidate the physiological mechanisms responsible for the observed connections between personality traits and physical health.

Keywords: Personality, Interleukin-6, Inflammation, Health, Impulsivity, C-reactive protein

There is now a substantial body of research showing that individuals high on Neuroticism and low on Conscientiousness are particularly vulnerable to poor health outcomes. For example, Neuroticism and Conscientiousness are associated with chronic illnesses (Goodwin & Friedman, 2006), physical health (Löckenhoff et al. 2008), and, ultimately, mortality (Wilson et al. 2004; Terracciano et al. 2008b). The negative prognostic implications of high Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness are due, at least in part, to poor health habits: These individuals are more likely to smoke, eat too much, and engage in other risky behaviors (Terracciano et al. 2008a, Terracciano et al. 2009). Less is known, however, about the links between personality traits and physiological biomarkers of morbidity and mortality. This study examines whether Neuroticism and Conscientiousness are associated with immune dysfunction, in particular a pro-inflammatory state.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a peripheral marker of chronic inflammation that increases with age and is implicated in a wide range of health outcomes (for a review, see Maggio et al. 2006). IL-6 is an inflammatory cytokine that promotes inflammation in response to infection or injury. Although beneficial in response to acute injuries, chronic production of IL-6 leads to increased morbidity and mortality. Higher levels of IL-6 are associated with frailty and disability among the elderly, and elevated IL-6 has been linked to numerous chronic conditions, such as diabetes, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular disease.

Research on IL-6 and all the traits that define the Five-Factor Model of personality has been relatively sparse. Because individuals suffering from depression often have elevated levels of IL-6 (Bremmer et al. 2008, Gimeno et al. 2009), researchers interested in personality have focused primarily on the emotion-related traits of Neuroticism and Extraversion. Despite the links between IL-6 and depression-related symptoms, some studies have failed to find an association between IL-6 and Neuroticism (Chapman et al. 2009). Although consistent across well-powered studies (>1,500 participants), the association between depressive symptoms and IL-6 is modest in magnitude (r=.06) (Penninx et al. 2003; Davidson et al. 2009). As such, the small sample sizes (<150 participants) that studies of Neuroticism-related traits typically rely on are underpowered to reliably detect small effects. Further, some evidence suggests that, rather than negative emotionality in general, inflammation may be more strongly related to the hostility component of Neuroticism (Marsland et al. 2008).

Extraversion, in contrast, is thought to be protective against inflammation. After being exposed to rhinovirus, for example, participants high in positive emotionality had lower nasal lavage IL-6, as well as fewer symptoms (Doyle et al. 2006). Among healthy adults, higher scores on Extraversion-related constructs are associated with lower circulating IL-6 (Chapman et al. 2009). This association, however, may be due more to the activity-related component of Extraversion rather than the positive emotionality component (Chapman et al. 2009).

We are unaware of any studies that have examined the link between IL-6 (or inflammation more generally) and Conscientiousness. An individual's disposition, such as his/her Conscientiousness, may be directly associated with physiological mechanisms, or indirectly associated with these mechanisms through health-related behaviors (Adler & Matthews, 1994). Given that Conscientiousness is consistently associated with beneficial health behaviors and negatively associated with health-risk behaviors (Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006), conscientious individuals may have lower levels of IL-6.

Studies of personality and physical health typically do not focus on critical medical biomarkers, such as IL-6, in large community-based samples. The present research examines the association between personality and circulating levels of IL-6 in a large and relatively homogenous sample of Italians from Sardinia. Although not always associated with negative health outcomes (Martin et al. 2007), we expect Neuroticism to be associated with greater IL-6, as individuals high on this trait often engage in the behaviors that increase inflammation (e.g., smoking). Further, because of its association with both health behaviors and disease, we expect that individuals low in Conscientiousness will also have higher levels of IL-6. In addition, because hostility and activity have been associated with IL-6, we expect that the hostility facet of Neuroticism (N2: Angry Hostility) and the activity facet of Extraversion (E4: Activity) will be associated with greater and lower IL-6, respectively. We also examine whether these associations hold controlling for relevant covariates and whether cigarette smoking and Body Mass Index (BMI) mediate the personality-IL-6 relations. Further, because of sex differences and age-related changes for both personality and IL-6, we test age and sex as moderators. We also test the associations between personality and C-reactive protein, a related marker of chronic inflammation (Harris et al. 1999). Finally, we test whether personality predicts which individuals have IL-6 levels that exceed clinically-relevant thresholds for disability and mortality.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from the SardiNIA project, a large, on-going multidisciplinary study of the genetic and environmental basis of complex traits and age-related processes (Pilia et al. 2006). Approximately 62% of the population (N = 6,148 individuals; 56.7% female), aged 14 to 102 years, from a cluster of four towns in the Lanusei Valley enrolled in the study. This founder population was chosen for the larger project because such populations tend to have greater genetic and environmental homogeneity than more diverse populations. The current study includes a total of 4,923 participants (57% female) who completed the self-report personality questionnaire and were assessed for IL-6. Age ranged from 14 to 82 (M = 39.31; SD = 14.72).

Personality Assessment

Personality traits were assessed using the Italian version (Terracciano, 2003) of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R), which measures 30 facets, six for each of the five major dimensions of personality (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The 240 items are answered on a five-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree to strongly agree; scales are roughly balanced to control for the effects of acquiescence. In this sample, the NEO-PI-R showed good psychometric properties: internal consistency reliabilities for the five factors ranged from 0.80 to 0.87. The factor structure replicated the American normative structure at the phenotypic and genetic level (Pilia et al. 2006; Costa et al. 2007). Raw scores were converted to T-scores (M=50, SD=10) using American combined-sex norms (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Assays

IL-6

. Serum IL-6 levels were measured by Quantikine High Sensitive Human IL-6 Immunoassay (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN), according to manufacturer's instructions. This method employs solid-phase ELISA techniques and has a detection limit of 0.016-0.110 pg/mL, with mean sensitivity of 0.039 pg/mL. The intra-assay coefficient of variations (CVs) were 6.9% to 7.4% over the range 0.43-5.53 pg/mL. Across the entire sample, IL-6 had a mean of 2.75 pg/mL (SD = 2.35). Because the distribution of IL-6 showed the typical right skew, we took the natural log to normalize the distribution. The correlation between the raw and transformed data was .91.

High sensitivity C-reactive protein

Serum levels of high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were measured by the high sensitivity Vermont assay (University of Vermont, Burlington), an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay calibrated with WHO Reference Material (Macy et al., 1997). The lower detection limit of this assay is 0.007 mg/l, with an inter-assay coefficient of variation of 5.14%.

Covariates

In addition to age and gender, we controlled for a number of variables that are known to have an effect on IL-6: current smoking status (smokers [23%] versus never/former [77%]), BMI derived from staff-assessed weight and height (M=24.77, SD=4.42), aspirin use within the last two weeks (8%), and disease burden. Disease burden was defined as the sum of diseases or disorders participants were currently enduring from 16 different classes of disease (e.g., neurological, immunological). In the current sample, disease burden ranged from 0 to 9, out of a possible 16 (median = 1). In the current sample, IL-6 correlated .28 (p < .01) with age, .05 (p < .01) with sex, .27 (p < .01) with BMI, .03 (p < .05) with smoking, .03 (p < .05) with disease burden, and .02 (ns) with aspirin use.

Analytic Strategy

We examined the association between personality and IL-6 in several ways. First, we examined the partial correlations between personality and IL-6, controlling for sex and age and the other covariates. In addition to the Pearson correlations, to ensure that the correlations are not distorted by outliers, we also present the non-parametric Spearman rank correlations on age and sex residualized scores. Second, we tested whether these associations were moderated by either sex or age, using Aiken and West's (1991) methodology for testing interactions. We used age both as a continuous variable and, because of a nonlinear increase in IL-6 in old age, a dichotomous variable split at age 65. Third, to follow-up on the broad domain-level findings, we examined the association between IL-6 and the more specific facets of personality. Fourth, we tested whether the findings held when individuals with acute inflammation were excluded from the analyses and if the findings were similar using a related marker of systemic inflammation, C-reactive protein. Fifth, we tested whether the covariates mediated the association between personality and IL-6. Finally, we used logistic regression to test whether personality predicts which participants would exceed clinical thresholds for increased risk of disability and mortality.

Results

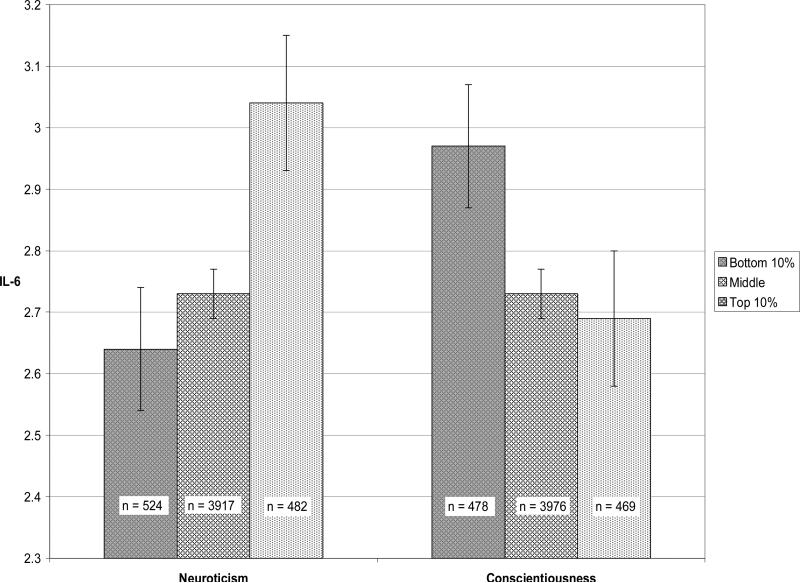

We first correlated IL-6 with the five major personality dimensions, controlling for sex and age (see Table 1). Consistent with our expectations, both higher Neuroticism and lower Conscientiousness scores were related to greater circulating levels of this inflammatory marker (see Figure 1). Thus, two major personality dimensions commonly implicated in health-related behaviors and outcomes – high Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness – are also associated with high circulating IL-6, a condition associated with chronic disease and frailty. The remaining three personality dimensions were unrelated to IL-6. The correlations remained significant when we controlled for current smoking status, BMI, aspirin use in the last 2 weeks, and disease burden. Thus, although modest, the associations were remarkably stable, even when accounting for factors known to increase circulating levels of IL-6, and they are of similar magnitude to the association often reported between IL-6 and depression in large-scale studies (Penninx et al. 2003; Davidson et al. 2009, Gimeno et al. 2009).

Table 1.

Associations between Markers of Inflammation and Personality Controlling for Sex and Age

| Correlations |

Logistic Regressions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson | Spearman | OR (95% CI)a IL-6 ≥ 3.19 mg/mL | ||

| Personality | Log IL-6 | Raw IL-6 | Raw hsCRP | |

| Neuroticism | .04** | .06** | .03* | 1.12 (1.04-1.21)** |

| Extraversion | -.02 | .00 | .00 | .94 (.87-1.02) |

| Openness | -.01 | .01 | -.02 | .96 (.89-1.03) |

| Agreeableness | -.02 | -.04** | -.02 | .96 (.89-1.04) |

| Conscientiousness | -.07** | -.10** | -.03* | .87 (.81-.93)** |

| Facets | ||||

| N1: Anxiety | -.01 | .00 | .00 | .99 (.92-1.08) |

| N2: Angry Hostility | .05** | .06** | .03* | 1.14 (1.06-1.23)** |

| N3: Depression | .02 | .04** | .02 | 1.08 (1.01-1.16)*b |

| N4: Self-Consciousness | .02 | .02 | .01 | 1.04 (.98-1.12) |

| N5: Impulsivity | .05** | .09** | .08** | 1.15 (1.07-1.24)** |

| N6: Vulnerability | .03* | .05** | .02 | 1.08 (1.01-1.15)* |

| E1: Warmth | -.02 | -.02 | .01 | .98 (.91-1.05) |

| E2: Gregariousness | -.02 | .00 | .00 | .94 (.88-1.01) |

| E3: Assertiveness | -.01 | .00 | .00 | .96 (.89-1.05) |

| E4: Activity | -.03* | -.03* | -.04** | .90 (.84-.98)* |

| E5: Excitement-Seeking | .01 | .04** | .02 | 1.02 (.94-1.10) |

| E6: Positive Emotions | .00 | .01 | .02 | .99 (.93-1.06) |

| O1: Fantasy | .00 | .02 | -.01 | .96 (.90-1.04) |

| O2: Aesthetics | -.02 | -.01 | -.03* | .96 (.89-1.04) |

| O3: Feelings | -.01 | .02 | -.01 | .95 (.88-1.02) |

| O4: Actions | .00 | .03* | -.01 | .99 (.92-1.06) |

| O5: Ideas | -.01 | -.01 | .00 | .97 (.90-1.04) |

| O6: Values | .00 | .01 | -.01 | 1.00 (.93-1.08) |

| A1: Trust | -.02 | -.04** | -.03* | .96 (.90-1.02) |

| A2: Straightforwardness | -.02 | -.03* | -.02 | .96 (.90-1.03) |

| A3: Altruism | -.02 | -.03* | .00 | .98 (.91-1.05) |

| A4: Compliance | -.02 | -.05** | -.04** | .95 (.90-1.02) |

| A5: Modesty | .00 | .00 | .00 | 1.03 (.96-1.11) |

| A6: Tender-Mindedness | .00 | .00 | .02 | 1.02 (.96-1.09) |

| C1: Competence | -.04** | -.06** | .00 | .94 (.88-1.01) |

| C2: Order | -.06** | -.07** | -.04* | .89 (.83-.95)** |

| C3: Dutifulness | -.07** | -.09** | -.01 | .87 (.81-.93)** |

| C4: Achievement Striving | -.03* | -.04** | -.01 | .92 (.86-.99)* |

| C5: Self-Discipline | -.07** | -.09** | -.05** | .86 (.80-.92)** |

| C6: Deliberation | -.04** | -.06** | -.03 | .95 (.89-1.02) |

Note. N = 4923. OR = Odds Ratio. CI = Confidence Interval. IL-6 = Interleukin-6. hsCRP = High sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Per one standard deviation increase in personality.

Logistic regression effect reduced to non-significance when controlling for smoking, BMI, aspirin use, and disease burden.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Estimated marginal means of raw IL-6 measurements by groups scoring in the top and bottom 10% of the distribution on Neuroticism and Conscientiousness, controlling for sex and age.

We next tested for moderators of the personality-IL-6 associations. Neither sex nor age – measured as a continuous variable or dichotomized at age 65 – moderated the association between personality and IL-6. Although not a statistically significant interaction, the findings for Neuroticism and Conscientiousness were slightly stronger among participants 65 years of age and older (r = .07 for Neuroticism and r = -.16 for Conscientiousness, both ps < .05).

The more specific facets of personality revealed an interesting pattern of associations (see Table 1). Consistent with previous research (Marsland et al. 2008), the hostility component of Neuroticism, rather than other aspects of negative affectivity, was associated with higher IL-6. Similarly, although factor-level Extraversion was unrelated to IL-6, the activity facet showed the expected negative correlation, whereas the positive emotionality aspects of Extraversion were unrelated to IL-6. In addition, N5: Impulsivity and N6: Vulnerability correlated positively and, following the factor-level association, all facets of Conscientiousness correlated negatively with IL-6.

In addition to the Pearson correlations, we examined Spearman rank correlations between personality and the untransformed IL-6 scores, residualized for age and sex (see Table 1). In this set of analyses, we found the same pattern of results, with a few additional significant correlations: IL-6 correlated negatively with Agreeableness and four of its facets, A1: Trust, A2: Straightforwardness, A3: Altruism, and A4: Compliance, and positively with N3: Depression, E5: Excitement-Seeking, and O4: Actions. Interestingly, the negative correlation with Agreeableness is consistent with the literature on antagonism-related constructs that shows that antagonistic individuals tend to have higher levels of IL-6. (Sjögren et al. 2006; Marsland et al. 2008).

To ensure that the effects were not due to individuals experiencing acute inflammation, we ran two additional sets of analyses. First, we re-ran the correlations after excluding participants who had levels of IL-6 that were two standard deviations above the mean. The correlations between this truncated IL-6 variable and personality were virtually identical to the correlations on the entire sample. Second, because C-reactive protein measures more systemic inflammation than IL-6, we also tested whether personality was associated with this marker of inflammation. We examined Spearman correlations between personality and C-reactive protein, residualized for sex and age. Albeit with slightly weaker correlations, we replicated the basic findings for Neuroticism and Conscientiousness, as well as several of the facets, including N5: Impulsivity and C5: Self-Discipline (see Table 1).

Although the correlations remained significant after controlling for behavioral risk factors known to be associated with IL-6, we explored the possibility that these variables may partially mediate the association between personality and IL-6. We simultaneously tested smoking, BMI, aspirin use, and disease burden as mediators, controlling for sex and age, using bootstrapping techniques (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). BMI and smoking both accounted for part of the association between N5: Impulsivity and IL-6: Impulsive participants had high circulating levels of IL-6, in part, because of their smoking habits and weight (point estimates = .0030 and .0011, 95% CIs = .0021-.0040 and .0006-.0017 for smoking and BMI, respectively, ps < .05). In addition, smoking mediated four facets of Conscientiousness (C1: Competence, C3: Dutifulness, C4: Achievement Striving, and C6: Deliberation; median point estimate = -.0005, 95% CI = -.001 to -.0001, p < .05) and BMI mediated C2: Order (point estimate = -.0013, 95% CI = -.002 to -.0006, p < .05), indicating participants low in Conscientiousness had higher IL-6, in part, because they smoked and were overweight (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations between Personality and the Significant Mediators and Between Personality and IL-6 Controlling for the Mediators

| Mediators |

Log IL-6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality trait | Smoking | BMI | Disease Burden | Aspirin | |

| N5: Impulsivity | .09**† | .11**† | .03* | .02 | .03* |

| C1: Competence | -.04*† | .00 | -.02 | .00 | -.03** |

| C2: Order | -.03* | -.05**† | .01 | .01 | -.05** |

| C3: Dutifulness | -.04*† | .01 | .00 | -.01 | -.06** |

| C4: Achievement Striving | -.04*† | .00 | .02 | .00 | -.02 |

| C6: Deliberation | -.08**† | .00 | -.02 | .00 | -.03* |

Note. N = 4923.

indicates significant mediator between the personality trait and IL-6.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Finally, we tested whether personality was associated with a greater risk for elevated levels of IL-6 above a clinically-significant threshold. Previous research has identified IL-6 levels ≥ 3.19 pg/mL as a threshold that confers greater risk of mortality (Harris et al. 1999). We used logistic regression, controlling for sex and age, to test whether personality was associated with a greater relative risk for supra threshold levels of IL-6 (approximately 26% of the current sample). The results from the logistic regressions paralleled the correlational analyses (see Table 1). For every one standard deviation increase in Neuroticism, for example, the risk of exceeding this threshold increased by 12%, whereas for every one standard deviation increase in Conscientiousness, the risk of exceeding this threshold was reduced by 13%. Further, those participants who either scored in the top 10% of the distribution of Neuroticism or in the bottom 10% of Conscientiousness were almost 40% more likely to have levels of IL-6 greater than 3.19 pg/mL (OR = 1.37, CI = 1.09-1.71 and OR = 1.40, CI = 1.12-1.75, for Neuroticism and Conscientiousness, respectively, ps < .05). By comparison, (male) sex increased the risk of exceeding the clinical threshold by about 20% (OR = 1.21, CI = 1.06-1.38, p < .05) and for every decade increase in age, risk increased by about 30% (OR = 1.34, CI = 1.28-1.40, p < .05).

Discussion

Consistent with the literature on personality and health-related behaviors and outcomes, Neuroticism and Conscientiousness had the expected associations with IL-6: High Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness were associated with greater circulating levels of this inflammatory marker. Controlling for a variety of factors known to increase levels of IL-6, including smoking and disease burden, did not reduce these correlations to non-significance. Previous research on personality and health has focused primarily on self-reported subjective health or the ultimate health outcome – mortality – rather than the more proximal physiological mechanisms that mediate personality and physical health. The current research joins the growing effort to elucidate these links, particularly the connection between personality traits and IL-6, a marker of inflammation known to increase the risk of morbidity and mortality.

Beyond the five broad factors, the facet-level analyses provided additional insights into the specific aspects of personality associated with greater inflammation. IL-6 was associated with different aspects of impulsivity, from the inability to resist cravings (high Impulsiveness), to difficulty staying on task (low Self-Discipline), to the tendency to make hasty decisions without careful consideration (low Deliberation). Individuals with higher IL-6 were also disorganized (low Order) and unable to strictly adhere to their own principles (low Dutifulness). For these individuals, the temptations of smoking, food, and a sedentary lifestyle may be too great to resist, despite the consequences, and this inability to maintain a healthy lifestyle may contribute to greater levels of IL-6. And indeed, we found that smoking and weight partially mediated these associations. In particular, individuals with impulsive-related personality traits tend to smoke (Terracciano et al. 2008a) and are overweight (Terracciano et al. 2009), and these behaviors, in turn, are associated with higher levels of IL-6. Finally, the negative association between activity and IL-6 is notable, as the decline in activity typically observed in older adulthood (Terracciano et al. 2005) may correspond with increases in inflammation also observed at this stage of the life course (Harris et al. 1999).

Our findings replicate and extend previous research on the association between personality and IL-6. Consistent with the depression literature (Penninx et al. 2003; Davidson et al. 2009), trait Neuroticism was associated with higher levels of IL-6, as was the hostility facet, which has also been associated with greater IL-6 (Marsland et al. 2008). Although some have not found an association between IL-6 and Neuroticism (e.g., Chapman et al. 2009), this may be due to differences in sampling strategies (e.g., age distribution, community versus patient, etc). In addition, large samples are necessary to be able to detect small effects reliably. Finally, consistent with Chapman and colleagues (2009), the activity component of Extraversion was associated with lower levels of IL-6, whereas the positive affect aspects of this trait were not. To our knowledge, we are the first to report an association between IL-6 and Conscientiousness.

Reciprocal interactions between personality and inflammation likely serve to influence and reinforce each other over time. An individual's characteristic way of thinking, feeling, and behaving may shape the circumstances that lead to increased inflammation. For example, compared to emotionally stable individuals, individuals vulnerable to stress may perceive more situations as stressful, yet lack the necessary resources to cope with the negative emotions evoked during such situations. This tendency to experience negative emotions contributes to chronic inflammation over time (Stewart et al. in press). Unhealthy behaviors represent another pathway that may account, at least in part, for the relation between personality and inflammation. As noted above, individuals who are disorganized and lack self-discipline have higher levels of IL-6, in part, because of their unhealthy behaviors.

The indirect effect through health-risk behaviors, however, only partially accounts for the association between personality and levels of IL-6. Thus, in addition to health-risk behaviors, personality may have a direct effect on an individual's physical health through physiological mechanisms. For example, Neuroticism-related constructs have consistently been associated with activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical (HPA) axis (e.g., Mangold & Wand, 2006, Tyrka et al. 2008). Although the research on Conscientiousness and HPA reactivity is still in its infancy, some evidence suggests that conscientious individuals have lower physiological reactivity in response to a stressor and return more quickly to baseline (Zobel et al. 2004) and positive psychological traits in general are associated with lower HPA reactivity (Chida & Hamer, 2008). As such, personality has both independent and incremental effects on health, even after controlling for major behavioral contributors to health-related outcomes.

Chronic psychosocial stressors can also exact a physiological toll on the individual. For example, caregivers of cancer patients show increases in inflammatory markers over time (Rohleder et al. 2009) and chronic interpersonal difficulties are associated with an increased sensitivity to hyperinflammatory responses (Miller et al. 2009). Both high Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness are associated with environmental stressors, such as less successful careers (Judge et al, 1999), the inability to make decisions at work (Sutin & Costa, in press), and lower income (Sutin et al. 2009) and marital adjustment (Bouchard et al. 1999). Over time, such stressors can have deleterious effects on physical health. For these individuals, the social environments in which they function may compound the risk for chronic inflammation.

At the same time, genetic predispositions or environmental factors that increase inflammation may likewise contribute to an individual's personality. For example, experimentally raising circulating levels of IL-6 leads to increases in state negative affectivity and decreases in performance on memory tasks (Reichenberg et al. 2001). Similarly, chronic inflammation due to diseases or other causes may reduce an individual's emotional resiliency or the cognitive resources necessary to control impulsive behavior. Further, mutual feedback between personality and IL-6, as well as other inflammatory mediators, may progressively increase morbid tendencies over time. We found some evidence of this in the current study: The correlations between IL-6 and Neuroticism and Conscientiousness were stronger among the older participants in our sample. In future research, multiple assessments of personality and levels of IL-6 over time are needed to test for this potential reciprocal influence.

Despite the inherent limitation of a cross-sectional assessment, the present study had several strengths, including a large community sample that ranged across most of the lifespan and a comprehensive measure of personality that covered the facets, as well as the five major dimensions, of personality. Our sample, however, was derived from a rural area in Sardinia, which differs in several respects from more metropolitan areas. Despite lifestyle differences and fewer economic opportunities, personality traits in this sample do not differ from personality measured in other Italian samples (Costa et al. 2007). The present research moves beyond the typical self-reported health ratings to identify a critical medical biomarker associated with personality. Interestingly, our findings for this physiological marker mirror those typically observed for self-reported health-related outcomes: Individuals with the combination of high Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness are particularly vulnerable to elevated levels of this inflammatory cytokine. Identifying such biomarkers will help to elucidate the physiological mechanisms that link personality traits and physical health.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported entirely by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging. Paul Costa receives royalties from the Revised NEO Personality Inventory.

References

- Adler N, Matthews K. Health psychology: Why do some people get sick and some stay well? Annual Review of Psychology. 1994;45:229–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.45.020194.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard G, Lussier Y, Sabourin S. Personality and marital adjustment: Utility of the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:651–660. [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer MA, Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Penninx BWJH, Dik MG, Hack CE, Hoogendijk WJG. Inflammatory markers in late-life depression: Results from a population-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;106:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Khan A, Harper M, Stockman D, Fiscella K, Walton J, Duberstein P, Talbot N, Lyness JM, Moynihan J. Gender, race/ethnicity, personality, and interleukin-6 in urban primary care patients. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23:636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Hamer M. Chronic psychosocial factors and acute physiological responses to laboratory-induced stress in healthy populations: A quantitative review of 30 years of investigations. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:829–885. doi: 10.1037/a0013342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr., McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr., Terracciano A, Uda M, Vacca L, Mameli C, Pilia G, Zonderman AB, Lakatta E, Schlessinger D, McCrae RR. Personality traits in Sardinia: Testing founder population effects on trait means and variances. Behavior Genetics. 2007;37:376–387. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KW, Schwartz JE, Kirkland SA, Mostofsky E, Fink D, Guernsey D, Shimbo D. Relation of inflammation to depression and incident coronary heart disease (from the Canadian Nova Scotia Health Survey [NSHS95] Prospective Population Study). American Journal of Cardiology. 2009;103:755–761. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle WJ, Gentile DA, Cohen S. Emotional style, nasal cytokines, and illness expression after experimental rhinovirus exposure. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2006;20:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS. The multiple linkages of personality and disease. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2008;22:668–675. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno D, Kivimäki M, Brunner EJ, Elovainio M, De Vogli R, Steptoe A, Kumari M, Lowe GD, Rumley A, Marmot MG, Ferrie JE. Associations of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 with cognitive symptoms of depression: 12-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:413–423. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Friedman HS. Health status and the five-factor personality traits in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11:643–654. doi: 10.1177/1359105306066610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, Corti MC, Wacholder S, Ettinger Jr WH, Heimovitz H, Cohen HJ, Wallace R. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. American Journal of Medicine. 1999;106:506–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge TA, Higgins CA, Thoresen CJ, Barrick MR. The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel Psychology. 1999;52:621–652. [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff CE, Sutin AR, Ferrucci L, Costa PT., Jr. Personality traits and subjective health in the later years: The association between NEO-PI-R and SF-36 in advanced age is influenced by health status. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42:1334–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Maggio M, Guralnik JM, Longo DL, Ferrucci L. Interleukin-6 in aging and chronic disease: A magnificent pathway. Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2006;61:575–584. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangold DL, Wand GS. Cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone responses to naloxone in subjects with high and low neuroticism. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60:850–855. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland AL, Prather AA, Petersen KL, Cohen S, Manuck SB. Antagonistic characteristics are positively associated with inflammatory markers independently of trait negative emotionality. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2008;22:753–761. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LR, Friedman HS, Schwartz JE. Personality and mortality risk across the life span: The importance of conscientiousness as a biopsychosocial attribute. Health Psychology. 2007;26:428–436. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Rohleder N, Cole SW. Chronic interpersonal stress predicts activation of pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways 6 months later. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:57–62. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318190d7de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BWJH, Kritchevsky SB, Yaffe K, Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Rubin S, Ferrucci L, Harris T, Pahor M. Inflammatory markers and depressed mood in older persons: Results from the health, aging and body composition study. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:566–572. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01811-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilia G, Chen WM, Scuteri A, Orrú M, Albai G, Dei M, Lai S, Usala G, Lai M, Loi P, Mameli C, Vacca L, Deiana M, Olla N, Masala M, Cao A, Najjar SS, Terracciano A, Nedorezov T, Sharov A, Zonderman AB, Abecasis GR, Costa P, Lakatta E, Schlessinger D. Heritability of cardiovascular and personality traits in 6,148 Sardinians. PLoS Genetics. 2006;2:1207–1223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather AA, Marsland AL, Muldoon MF, Manuck SB. Positive affective style covaries with stimulated IL-6 and IL-10 production in a middle-aged community sample. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2007;21:1033–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenberg A, Yirmiya R, Schuld A, Kraus T, Haack M, Morag A, Pollmächer T. Cytokine-associated emotional and cognitive disturbances in humans. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:445–452. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohleder N, Marin TJ, Ma R, Miller GE. Biologic cost of caring for a cancer patient: Dysregulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:2909–2915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjögren E, Leanderson P, Kristenson M, Ernerudh J. Interleukin-6 levels in relation to psychosocial factors: Studies on serum, saliva, and in vitro production by blood mononuclear cells. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2006;20:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JC, Rand KL, Muldoon MF, Kamarck TW. A prospective evaluation of the directionality of the depression-inflammation relationship. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.011. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Costa PT, Jr., Miech R, Eaton WW. Personality and career success: Concurrent and longitudinal relations. European Journal of Personality. 2009;23:71–84. doi: 10.1002/per.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Costa PT., Jr. Reciprocal influences of personality and job characteristics across middle adulthood. Journal of Personality. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00615.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A. The Italian version of the NEO PI-R: Conceptual and empirical support for the use of targeted rotation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:1859–1872. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Löckenhoff CE, Crum RM, Bienvenu OJ, Costa PT., Jr. Five-factor model personality profiles of drug users. BMC Psychiatry. 2008a;8 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Löckenhoff CE, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L, Costa PT., Jr. Personality predictors of longevity: Activity, emotional stability, and conscientiousness. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008b;70:621–627. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817b9371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, McCrae RR, Brant LJ, Costa PT., Jr. Hierarchical linear modeling analyses of the NEO-PI-R scales in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:493–506. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracciano A, Sutin AR, McCrae RR, Deiana B, Ferrucci L, Schlessinger D, Uda M, Costa PT., Jr. Facets of personality linked to underweight and overweight. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:682–689. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a2925b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Wier LM, Price LH, Rikhye K, Ross NS, Anderson GM, Wilkinson CW, Carpenter LL. Cortisol and ACTH responses to the Dex/CRH Test: Influence of temperament. Hormones and Behavior. 2008;53:518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Mendes De Leon CF, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Personality and mortality in old age. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:110–116. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.p110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zobel A, Barkow K, Schulze-Rauschenbach S, Von Widdern O, Metten M, Pfeiffer U, Schnell S, Wagner M, Maier W. High neuroticism and depressive temperament are associated with dysfunctional regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system in healthy volunteers. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;109:392–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]