Abstract

A patient's ability to produce autologous neutralizing antibody (ANAB) to current and past HIV isolates correlates with reduced disease progression and protects against maternal–fetal transmission. Little is known about the effects of prolonged viral suppression on the ANAB response in pediatric HIV-infected patients receiving HAART because the virus is hard to isolate, except by special methods. We therefore assessed ANAB to pre-HAART PBMC virus isolates and post-HAART replication-competent virus (RCV) isolates recovered from latent CD4+ T-cell reservoirs in perinatally HIV-infected children by using a PBMC-based assay and 90% neutralization titers. We studied two infants and three children before and after HAART. At the time of RCV isolation (n = 4), plasma HIV RNA was <50 copies/ml. At baseline, four of five children had detectable ANAB titers to concurrent pre-HAART virus isolates. Although ANAB was detected in all subjects at several time points despite prolonged HAART and undetectable viremia, the response was variable. ANAB titers to concurrent post-HAART RCV and earlier pre-HAART plasma were present in 3 children suggesting prior exposure to this virus. Post-HAART RCV isolates had reduced replication kinetics in vitro compared to pre-HAART viruses. The presence of ANAB over time suggests that low levels of viral replication may still be ongoing despite HAART. The observation of baseline ANAB activity with earlier plasma against a later RCV suggests that the “latent” reservoir may be established early in life before HAART.

Introduction

The role of HIV neutralizing antibody (NAB) in the pathogenesis of HIV infection is controversial. Adults with primary infection have a brisk HIV-specific CTL response as early as 3 weeks, associated with a decrease in initial viremia. This response is still present 3–6 months later. However, the production of NAB to HIV has been reported as initially absent in primary adult infection, with delayed production by 3–6 months.1 Patients subsequently develop escape virus with reduced sensitivity to neutralization by concurrent autologous sera but may still produce antibody to earlier isolates.2 The ability to produce and maintain ANAB activity to new and previous HIV isolates has been correlated with slow disease progression or long-term nonprogressors with low viral loads in adults.3–5 In contrast, others have shown HIV CTL and cellular immune virus–specific CD4+ T-cell proliferative responses, as well as innate immunity, rather than NAB, as critical factors in control of HIV infection.6–8 However, NAB may be critical in the prevention of infection, as recently discussed.9

In early highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) given to adults with primary infection, structured treatment interruption was associated with increases in ANAB and the maintenance of viral suppression.10 Infants treated early with HAART (before 3 months of age) may respond to therapy with suppression of viremia, demonstrate increases in CD4+ T cells to normal levels, and develop gradual loss of HIV antibody. If the plasma viremia continues to be suppressed to undetectable levels over time, the infant may become HIV seronegative by 12–18 months of age.11

Initiation of HAART has been shown to decrease plasma viremia and lead to recovery of CD4+ T cells in HIV-infected patients. In these patients, CD4+ T cells have been shown to harbor replication-competent HIV (RCV) in both children and adults on HAART with prolonged, undetectable plasma viremia. RCV has been isolated from latent T cells in adults and children with prolonged viral suppression.12–17 It has been shown that a reservoir of virus persists in a “latent form” within CD4+ T cells circulating in blood and residing in lymphoid tissue as virion-associated RNA trapped in the follicular dendritic cell network of the germinal centers.

Currently, limited data exist on the effect of prolonged viral suppression with HAART on an individual's ability to produce and maintain ANAB to current or past HIV isolates in both HIV-infected infants and older children. We evaluated the ability of perinatally HIV-infected subjects to neutralize their autologous viral isolate and latent CD4+ T-cell RCV before and after initiation of HAART.

Materials and Methods

Patients

As part of a prospective study of perinatally HIV-infected subjects treated with HAART, five subjects defined as complete responders (CRs) were evaluated. Patients were categorized as CR if they had suppression of plasma HIV RNA levels <400 copies/ml, as measured by Amplicor standard HIV-1 Monitor Test and <50 copies/ml by the ultrasensitive Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor® Test, v1.5 when available (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).18 Plasma samples from the infants and children were used for neutralization of their autologous viral isolates over time. We selected five subjects for evaluation of sequential ANAB titers on the basis of available paired plasma samples and viral isolates. Infant A became a CR with undetectable viral load, but even with multiple attempts to isolate RCV, none was isolated. Therefore, the last HIV isolated from PBMCs was used to determine ANAB titers for this subject. T cells were monitored clinically by using basic flow cytometry. HAART was defined as a combination of three antiretroviral medications (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and protease inhibitors). Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians, and human subjects protocols were approved by the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell coculture

Blood was collected in EDTA tubes, and PBMCs were separated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (Robbins Scientific, Mountain View, CA). Pretreatment virus was isolated from PBMCs by HIV coculture according to National Institutes of Health, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Clinical Trials Group Laboratory Manual.19

Replication-competent viruses

Post-HAART viral isolates were recovered from CD4+ T-cell reservoirs by previously described methods using smaller blood volumes.13,14,16,17,20 Virus isolates were titered with TCID50, aliquoted, and frozen as virus stock at −70°C for future use. Before the stock virus was used in the neutralization assay experiments, the TCID50 was determined by using HIV-negative three-donor pooled PBMCs stimulated with mitogen phytohemagglutinin-P (PHA-P; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 48 h.

Autologous neutralizing antibody assay

ANAB assays were performed in a pooled donor PBMC-based assay as previously described on pre- and post-HAART viral isolates.9 In brief, patient plasma samples were heat inactivated at 56°C for 30 min, and serial twofold dilutions in growth medium were incubated in 96-well plates for 90 min with viral isolates of 200 and 400 TCID50/ml in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The 50 μl of 4 × 106/ml pooled HIV-negative donor PBMCs previously stimulated with PHA for 48 h was added to each well, which was 2 × 105/well [multiplicity of infection (MOI), 0.0005 and 0.0001]. Microplates were incubated at 37°C overnight (12–16 h) with heat-inactivated plasma, virus, and stimulated PBMCs. Cells were washed, centrifuged, and growth medium (RPMI 1640, 200 mM l-glutamine, 20% fetal calf serum, 10 U/ml interleukin-2, 50 Ul/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) was replaced on day 1 and day 3. Supernatant was harvested, and p24 antigen levels were determined by Coulter kinetics assay (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL) on days 5 and 7. ANAB assays with RCV were continued to day 10.

Neutralization was determined by evaluating the ANAB titer in comparison to the virus control with no patient plasma. ANAB titers were expressed as the reciprocal plasma dilution producing 90% (ANAB90%) or 50% (ANAB50%) neutralization compared with virus controls. An ANAB90% titer of ≥1:20 (20, as represented in Results) was considered a positive neutralization titer. A significant difference was defined as a twofold or more dilution change in ANAB titers. Any potential plasma ART was diluted ≥20 times in the first assay well.

Viral growth kinetics in patients with RCV

Viral isolates were evaluated in vitro with measurement of p24 antigen production over 10 days in HIV-negative–pooled three-donor PBMCs. The pre-HAART viruses were compared with post-HAART CD4+ T-cell RCV for viral kinetic growth patterns in four patients.

Results

We evaluated ANAB titers in five perinatally HIV-infected subjects. Clinical characteristics are described in Table 1. The timing of evaluation reflects the availability of HAART for subjects A and B as infants and C, D, and E as children. The percentage of CD4+ T cells rose to median 40% (range, 28–45) with HAART in all children.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics

| Subject | Age pre-HAART virus isolated (mos) | Age post-HAART virus isolated (mos) | Age started HAART (mos) | HIV RNA (copies/mL) pre-HAART | HIV RNA (copies/mL) post-HAART | CD4 % pre/post-HAART | CDC nadir classification | RCV isolated post-HAART (mos) | Duration HIV RNA < 50 copies/mL prior to post-HAART RCV (mos) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | 1 day | 9 | 3 | 369,541 | 52,722 | 29/30 | A2 | NA | NA |

| B | 3 | 22 | 3 | 1,223,892 | <50 | 20/40 | A2 | 19 | 16 |

| C | 42 | 61 | 48 | 173,209 | <50 | 32/45 | A1 | 13 | 13 |

| D | 88 | 128 | 88 | 31,118 | <50 | 27/28 | B2 | 40 | 36 |

| E | 78 | 122 | 80 | 242,606 | <50 | 23/40 | A3 | 42 | 40 |

| Median | 42 | 61 | 48 | 242,606 | < 50 | 27/40 | 29.5 | 16 | |

| Range | (1 day–88) | (9–128) | (3–88) | (31,118–1,233,892) | (<50–52,722) | (20–32)/(28–45) | (13–42) | (14–42) |

This table depicts the age when pre-HAART and post-HAART viral isolates were obtained and the clinical characteristics pre/post-HAART for all subjects. Age is presented in months (mos) unless indicated.

No RCV recovered after multiple attempts so post-HAART virus isolated from PBMC (with detectable plasma viral load) used for subject A prior to persistent viral suppression at 22 months of age.

NA, not applicable.

Detectable ANAB titers to pre-HAART viral isolates

ANAB titers to pre-HAART viral isolates with concurrent plasma were detected in four of five subjects, as depicted in Table 2A. In addition, all five subjects had detectable ANAB titers to this pre-HAART virus with plasma obtained over time while on HAART. ANAB titers were present in all five subjects, 28–57 months after the pre-HAART virus was isolated. No specific pattern was seen among patients in regard to a change in titers over time; two subjects had an increase of titers (B and D), whereas three subjects had a decrease but still detectable ANAB titers (A, C, and E).

Table 2A.

Anab90% Titers to Pre-HAART Viral Isolates

|

Subject A |

Subject B |

Subject C |

Subject D |

Subject E |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Pre-HAART virus isolated on 1st day of life | Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Pre-HAART virus isolated at 3 mos | Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Pre-HAART virus isolated at 42 mos | Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Pre-HAART virus isolated at 88 mos | Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Pre-HAART virus isolated at 78 mos |

| 1st day of life | 640 | 3 | <20 | 42 | 80 | 88 | 80 | 78 | 1280 |

| 6 | 20 | 12 | 40 | 46 | 20 | 128 | 1280 | 122 | 40 |

| 9 | 20 | 22 | 160 | 61 | 40 | ||||

| 47 | 40 | 60 | 40 | 70 | 20 | ||||

| 92 | <20 | ||||||||

Table 2B.

ANAB90% Titers to Post-HAART Viral Isolates

|

Subject A |

Subject B |

Subject C |

Subject D |

Subject E |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Post-HAART viral isolatea at 9 mos | Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Post-HAART viral isolate at 22 mos | Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Post-HAART viral isolate at 61 mos | Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Post-HAART viral isolate at 128 mos | Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Post-HAART viral isolate at 122 mos |

| 1st day of life | 20 | 3 | 20 | 42 | 1280 | 88 | 160 | 78 | <20 |

| 9 | <20 | 22 | 80 | 61 | 1280 | 128 | 80 | 122 | <20 |

All ANAB titers are expressed as the reciprocal of dilution which neutralized 90% of virus control. Positive ANAB titers are based on plasma dilution >1:20 (20).

Bold, ANAB titer of concurrent plasma and viral isolate; grey shaded background, ANAB titer while on HAART.

Age is presented in months (mos) unless indicated.

Post-HAART PBMC virus isolate.

Subject C was evaluated as an infant from birth with no ART, on dual ART, and to the time when HAART was available years later. ANAB titers against the birth virus isolated before ART increased from undetectable to a peak of 320, as seen in Table 3. However, the ability to neutralize the pre-HAART virus isolated at the age of 42 months decreased while on HAART.

Table 3.

Subject C: Anab90% Titers Over Time

|

Birth Virus |

Pre-HAART virus |

Concurrent virus and plasma |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | ANAB90% to birth virus isolated prior to ART | Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | ANAB90% to Pre-HAART virus isolated at 42 mos | Plasma samples collected age at (mos) | Concurrent ANAB90% over time | ||||

| No ART | Birth | <20 | Dual ART | 42 | 80 | No ART | Birth | <20 | |

| No ART | 2.5 | <20 | Dual ART | 46 | 20 | Dual ART | 15 | <20 | |

| Dual ART | 6 | 320 | HAART | 61 | 40 | Dual ART | 21 | <20 | |

| Dual ART | 11 | 160 | HAART | 70 | 20 | Dual ART | 33 | 160 | |

| Dual ART | 14 | 320 | HAART | 92 | <20 | Dual ART | 42 | 2560 | RCV |

| Dual ART | 20 | 160 | HAART | 63 | 2560 | RCV | |||

ANAB titers against the birth viral isolate (left column) and the pre-HAART viral isolate (middle column as presented in Table 2A). All titers are displayed with status of ART at evaluation. The ANAB titers for concurrent plasma and viral isolates are presented from birth to HAART with RCV as indicated (right column).

All ANAB titers are expressed as the reciprocal of dilution which neutralized 90% of virus control. Positive ANAB titers are based on plasma dilution >1:20 (20).

Bold; ANAB titer of concurrent plasma and viral isolate; grey shaded background: ANAB titer on HAART.

Age is presented in months (mos) unless indicated.

Subjects A and B had lower levels of ANAB overtime as infants treated early with HAART. One child, subject D, had an increase in ANAB, but the other two had a decrease in titers with HAART. The older children, C, D, and E, started HAART later in life at 48, 88, and 80 months of age, respectively. Of note, the decrease in ANAB titers between 1 and 9 months of age may reflect a decline in transplacental maternal antibody, but neutralizing antibody still was present at 47 months of age.

Detectable ANAB titers to replication-competent viruses isolated from latent CD4+ T cells

Four subjects had RCV isolated at a median of 30 months (range, 13–42 months) after the initiation of HAART. Concurrent ANAB titers to RCV were detected in three of four subjects, as presented in Table 2B. Subjects B, C, and D had detectable ANAB titers between 80 and 1,280, with concurrent plasma obtained against their post-HAART RCV. For the same three patients, their earlier pre-HAART plasma also neutralized the post-HAART RCV. Although subject E had no detectable ANAB to RCV with concurrent or previous pre-HAART plasma, this evaluation was performed after the longest duration on HAART, 42 months. No measurable concurrent ANAB titers to the post-HAART PBMC viral isolate were obtained at 9 months of age for subject A. However, a low level of ANAB to the post-HAART viral isolate with pre-HAAART plasma was detected.

HIV in vitro replication kinetics

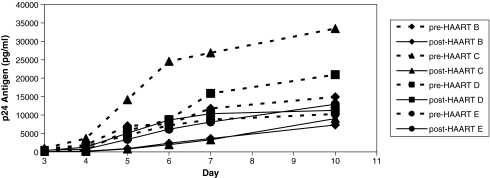

Viral isolates recovered from CD4+ T cell reservoirs while on HAART demonstrate reduced replication capacity as compared with pre-HAART viral isolates in the same normal pooled PBMCs in four subjects (B, C, D, and E). As seen in Fig. 1, the replication curves of the RCV are lower collectively and individually compared with pre-HAART viral isolates from the same patients. Mean p24 antigen production of the pre-HAART viruses on day 10 was 19,889 picograms/ml compared with post-HAART CD4+ T-cell reservoir viruses on day 10 of 10,139 pg/ml.

FIG. 1.

HIV viral isolate replication kinetics. Viral growth kinetics of post-HAART RCV compared with pre-HAART virus isolates measured in the same pooled PBMCs by HIV p24 antigen production for subjects B, C, D, and E. (Dotted line; pre-HAART from PBMCs, solid line; post-HAART RCV).

Discussion

Limited information has been available on the role of autologous neutralizing antibody in patients with viral suppression <50 cp/ml on HAART or elite suppressors because it is extremely difficult to isolate replicating virus from plasma or PBMCs without special methods.12,16,17,20 Studies in adults have used pseudoviruses generated from Env proteins from patient plasma or archival provirus to assess autologous neutralizing capacity to contemporary virus, an assay that also may have some limitations.21 We report the first study of ANAB capacity in HIV-infected pediatric subjects with plasma virus suppression (<50 copies/ml) on HAART by using replication-competent virus isolated from their own “latent CD4+ T cell reservoirs” and a PBMC-based assay.

We found perinatally HIV-infected pediatric patients had detectable ANAB titers to their pre-HAART original virus with concurrent and post-HAART plasma. These findings are similar to other reports in pediatrics in which perinatally HIV-infected rapid and nonrapid disease progressors with mono-, dual-, and no antiretroviral therapy were evaluated, and ANABs were produced to past isolates.22 Untreated HIV-infected adults have also been shown to neutralize past isolates more efficiently than contemporaneous virus as an ongoing dynamic process.2,23,24 Numerous studies in adults have shown that NAB responses have been slow to develop in acute HIV-infection and were not correlated with initial decrease in plasma viremia; however, ANAB responses developed over time.1,2,4,24 Others have found low but detectable levels of NAB to autologous virus in adults with chronic HIV infection who had varied levels of viral control.

Subjects in the current study were also able to neutralize replication-competent virus from “latent CD4+ T-cell reservoirs” concurrently with post-HAART plasma despite prolonged virus suppression as well as earlier pre-HAART plasma. The presence of ANAB against the contemporaneous RCV from CD4+ T-cell reservoirs in children indicates the possibility of ongoing low-level viral replication, even in those patients with prolonged undetectable plasma viremia, <50 copies/ml on HIV RNA ultrasensitive PCR assay. This is consistent with the reports of low levels of ANAB found in adults with viral suppression <50 HIV RNA copies/ml on HAART by the pseudovirus neutralizing assay on plasma generated clones.21 They also found similar neutralizing antibody levels in elite controllers but lower levels of HIV binding antibody than in chronic progressors. Other earlier studies in adult LTNP have shown the ability to neutralize primary isolates and heterologous viruses better than those with disease progression.4,25 However, Montefiori and colleagues26 found LTNP were unable to neutralize their replication-competent HIV with concurrent autologous serum, which differs from our pediatric subjects on HAART who had detectable ANAB to concurrent RCV. Variation in the ability to mount a NAB response to autologous virus may be a reflection of viral diversity and selective pressure on HIV. Both adults and children on HAART may have low-level HIV replication detected only by supersensitive real-time PCR techniques with current ART/HAART available drugs.26 It is unknown whether newer, more potent combination treatments with different mechanisms of actions developed in the future will change this.

The unique data on three infants treated early in life with dual ART or HAART show variable ANAB responses, depending on the consistency and timing of viral suppression in the child. However, the lack of HIV-neutralizing antibody responses in one infant is consistent with findings by Luzuriaga and colleagues11 in which infants treated early during primary infection (<3 months) may have decreased HIV antibody responses presumably due to lack of viral antigen stimulation. This finding has implications for the current recommendations for early HAART for all HIV-infected infants in the first year of life. Early antiretroviral therapy with protease inhibitor–based regimens initiated between 6 and 9 weeks of age significantly reduced infant mortality and HIV progression in a randomized trial of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy in South Africa.27 It is unknown whether later interruption of HAART in children at a more mature age will result in rebound ANAB, as seen in a subgroup of HAART-treated adults with acute infection.5

This current study is unique in that our patients were on potent HAART, and ANAB responses evaluated against autologous viruses and RCV were present even with undetectable plasma viremia. The presence of ANAB activity later in life may indicate that there is ongoing viral replication in lymphoid tissue, as reflected by the recovery of RCV from the latent CD4+ T cells. Therefore, HIV is not fully eradicated, even with prolonged plasma viral suppression with HIV RNA <50 copies/ml. ANAB titers to RCV further suggest that this latent replicating virus may continue to drive the production of neutralizing antibodies in some individuals.

Replication-competent HIV from CD4+ T-cell reservoirs has been recovered from children who have durable suppression on HAART.16,17 Isolation of these latent viruses may indicate that latency may be established early in infection and represent the major barrier to eradication of HIV. A critical question is whether the establishment or longevity of the latent HIV CD4+ T-cell reservoir pool would be influenced by extremely early potent HAART therapy in perinatally infected infants.

The finding of decreased replication capacity of virus isolated from CD4+ T cells compared with pre-HAART virus is of interest. These RCVs take an average of approximately 35 days in vitro in culture before there is evidence of p24 antigen production from primary isolation. It is unknown if these viruses are truly “less fit” than PBMC isolated viruses or have adapted to a “latent form.” All have been found to be R5 isolates. These viruses may reflect lower replication capacity and/or lower antigenic stimulation to drive production of neutralizing antibodies.

Although this is a small group, this is a detailed evaluation of ANAB titers in pediatric subjects with plasma viral suppression on HAART. With successful virologic suppression and clinical response to HAART, perinatally HIV-infected survivors can produce ANAB titers to their autologous HIV. The ability to neutralize RCV suggests that latent virus may be present early in infection. The complete eradication of HIV infection in patients with undetectable plasma viremia may not be attainable, as it appears that low-level replication is still present. This low-level viremia, currently not detectable by standard available virologic assays, is potentially a trigger for persistent ANAB activity. Further studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effects of HAART on the persistence of ANAB responses in pediatric HIV infection, particularly in infants treated early with HAART in the first year of life, with later treatment interruption.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank the HIV-infected patients and their families for their participation. We also thank Dr. Steven Wolinsky for his collaboration, the Glaser Pediatric Research Network, and University of California Los Angeles General Clinical Research Center (5M01RR000865-36). NC is a recipient of a NIH/NICHD Career Development Award 5K23HD051456. YJB is supported by National Institutes of Health R01HD37356 Viral and T-cell Dynamics and U01AI069401 Los Angeles Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Unit, and Los Angeles Brazil AIDS Consortium.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Pellegrin I. Legrand E. Neau D, et al. Kinetics of appearance of neutralizing antibodies in 12 patients with primary or recent HIV-1 infection and relationship with plasma and cellular viral loads. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;11:438–447. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199604150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arendrup M. Nielsen C. Hansen JE, et al. Autologous HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies: emergence of neutralization-resistant escape virus and subsequent development of escape virus neutralizing antibodies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura T. Yoshimura K. Nishihara K, et al. Reconstitution of spontaneous neutralizing antibody response against autologous human immunodeficiency virus during highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2002;85:53–60. doi: 10.1086/338099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montefiori DC. Pantaleo G. Fink LM, et al. Neutralizing, infection-enhancing antibody responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in long-term nonprogressors. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:60–67. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montefiori DC. Altfeld M. Lee PK, et al. Viremia control despite escape from a rapid and potent autologous neutralizing antibody response after therapy cessation in an HIV-1-infected individual. J Immunol. 2003;70:3906–3914. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koup RA. Sullivan JL. Levine PH, et al. Antigenic specificity of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity directed against human immunodeficiency virus in antibody-positive sera. J Virol. 1989;63:584–590. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.584-590.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koup RA. Pikora CA. Mazzara G, et al. Broadly reactive antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxic response to HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins precedes broad neutralizing response in human infection. Viral Immunol. 1991;4:215–223. doi: 10.1089/vim.1991.4.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koup RA. Robinson JE. Nguyen QV, et al. Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity directed by a human monoclonal antibody reactive with gp120 of HIV-1. Aids. 1991;5:1309–1314. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickover R. Garratty E. Yusim K, et al. Role of maternal autologous neutralizing antibody in selective perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 escape variants. J Virol. 2006;80:6525–6533. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02658-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richman DD. Wrin T. Little SJ, et al. Rapid evolution of the neutralizing antibody response to HIV type 1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4144–4149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630530100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luzuriaga K. McManus M. Catalina M, et al. Early therapy of vertical human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection: control of viral replication and absence of persistent HIV-1-specific immune responses. J Virol. 2000;74:6984–6991. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6984-6991.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finzi D. Blankson J. Siliciano JD, et al. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat Med. 1999;5:512–517. doi: 10.1038/8394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong JK. Hezareh M. Gunthard HF, et al. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science. 1997;278:1291–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chun TW. Carruth L. Finzi D, et al. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1997;387:183–188. doi: 10.1038/387183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chun TW. Engel D. Berrey MM, et al. Early establishment of a pool of latently infected, resting CD4(+) T cells during primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8869–8873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Equils O. Garratty E. Wei LS, et al. Recovery of replication-competent virus from CD4 T cell reservoirs and change in coreceptor use in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children responding to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:751–757. doi: 10.1086/315758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Persaud D. Pierson T. Ruff C, et al. A stable latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4(+) T lymphocytes in infected children. J Clin Invest. 2000;05:995–1003. doi: 10.1172/JCI9006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickover RE. Dillon M. Gillette SG, et al. Rapid increases in load of human immunodeficiency virus correlate with early disease progression and loss of CD4 cells in vertically infected infants. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1279–1284. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.5.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ACTG Laboratory Technologist Committee and Collaborating Investigators. AIDS Clinical Trial Group Laboratory Manual. Bethesda, MD: Division of AIDS, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finzi D. Hermankova M. Pierson T, et al. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science. 1997;278:1295–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey JR. Lassen KG. Yang HC, et al. Neutralizing antibodies do not mediate suppression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in elite suppressors or selection of plasma virus variants in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2006;80:4758–4770. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4758-4770.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geffin R. Hutto C. Andrew C, et al. A longitudinal assessment of autologous neutralizing antibodies in children perinatally infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology. 2003;310:207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moog C. Fleury HJ. Pellegrin I, et al. Autologous and heterologous neutralizing antibody responses following initial seroconversion in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol. 1997;71:3734–3741. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3734-3741.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pilgrim AK. Pantaleo G. Cohen OJ, et al. Neutralizing antibody responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in primary infection and long-term-nonprogressive infection. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:924–932. doi: 10.1086/516508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pikora CA. Sullivan JL. Panicali D, et al. Early HIV-1 envelope-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in vertically infected infants. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1153–1161. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Persaud D. Siberry GK. Ahonkhai A, et al. Continued production of drug-sensitive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in children on combination antiretroviral therapy who have undetectable viral loads. J Virol. 2004;78:968–979. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.968-979.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Violari A. Cotton MF. Gibb DM, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2233–2244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]