Abstract

Objectives

To identify factors that are significantly associated with dentists’ use of specific caries preventive agents in adult patients, and whether dentists who use one preventive agent are also more likely to use certain others.

Methods

Data were collected from 564 practitioners in The Dental Practice-Based Research Network, a multi-region consortium of participating practices and dental organizations.

Results

In-office topical fluoride was the method most frequently used. Regarding at-home preventive agents, there was little difference in preference between non-prescription fluoride, prescription fluoride, or chlorhexidine rinse. Dentists who most frequently used caries prevention were also those who regularly perform caries risk assessment and individualize caries prevention at the patient level. Higher percentages of patients with dental insurance were significantly associated with more use of in-office prevention modalities. Female dentists and dentists with more-recent training were more likely to recommend preventive agents that are applied by the patient. Dentists who reported more-conservative decisions in clinical treatment scenarios were also more likely to use caries preventive agents. Groups of dentist who shared a common preference for certain preventive agents were identified. One group used preventive agents selectively, whereas the other groups predominately used either in-office or at-home fluorides.

Conclusions

Caries prevention is commonly used with adult patients. However, these results suggest that only a subset of dentists base preventive treatments on caries risk at the individual patient level.

Introduction

The value of dentist- or patient-administered caries preventive agents is supported by a number of studies (1–4). In addition, current evidence supports their use as alternatives to restoration before demineralization has produced a cavitated lesion (5–7).

The most frequently studied caries prevention modality is fluoride use in children (8–12). Knowledge of dentists’ clinical decisions related to caries preventive agents in adults is limited, but existing data on the provision of specific procedures and numbers of procedures recommended for specific patients demonstrate substantial variation (13–16). Several reasons for this have been suggested. These include the fact that some clinicians are not confident of their ability to detect early lesions (17) and/or to arrest the disease and remineralize enamel (7). Nevertheless, it appears that other clinicians practice minimally-invasive dentistry and monitor early lesions after initial treatment to ensure that the carious activity is arrested and the enamel has been remineralized (13). Developing a better understanding of current dental practice patterns will allow organizations to better target training and information transfer to foster movement of scientific advances into routine clinical practice.

There are few studies documenting dentist, patient, or practice variables associated with the use of specific agents for caries prevention or management. One such study among Australian dentists has reported that topical fluoride was administered more often to patients when they were of higher socioeconomic status, but no associations were found with patient age, gender, or insurance status. Unfortunately, the use of other caries preventive agents was not considered (14). This and other studies have demonstrated that there is great variability in use of prevention as dentists may choose one or more agents over others or prefer to use a specific combination of agents (9,12–14).

Our data, although self-reported percentages of preventive services provided, have permitted the examination of patterns of care across six caries prevention methods. The aims of this study were to test the hypotheses that: 1) there are statistically significant differences in the use of these preventive agents; 2) that a combination of practice patterns (dentist, patient, or practice variables) are significantly associated with use of specific caries preventive agents; 3) that dentists who use one preventive agent are also more likely to use certain others; and 4) that groups of dentists can be identified with similar preventive preferences.

Methods

Network Dentists

The “Dental Practice-Based Research Network (DPBRN)” is a consortium of participating practices and dental organizations committed to advancing knowledge of dental practice and ways to improve it. DPBRN comprises five regions: AL/MS: Alabama/Mississippi, FL/GA: Florida/Georgia, MN: dentists employed by HealthPartners and private practitioners in Minnesota, PDA: Permanente Dental Associates in cooperation with Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, and SK: Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (18). Participants of the DPBRN were recruited through mass mailings to licensed dentists from the participating regions. As part of enrollment, all practitioner-investigators completed a DPBRN Enrollment Questionnaire about their practice characteristics and themselves. The enrollment questionnaire and other details about DPBRN are provided at http://www.DentalPBRN.org. DPBRN has a wide representation of practice types, treatment philosophies, and patient populations, including diversity with regard to the race, ethnicity, geography and rural/urban area of residence of both its practitioner-investigators and their patients. Analyses of these characteristics confirm that DPBRN dentists have much in common with dentists at large (19), while at the same time offering substantial diversity with regard to these characteristics (20).

Procedure

An additional questionnaire entitled “Assessment of Caries Diagnosis and Treatment” was sent to 970 DPBRN dentists who reported on the DPBRN Enrollment Questionnaire that they perform restorative dentistry in their practices. This questionnaire asked a range of questions that included caries-related diagnostic and clinical decision-making processes, caries risk assessment, and use of prevention techniques. The full questionnaire is publicly available at http://www.dpbrn.org/users/publications/Supplement.aspx. The 564 participating DPBRN dentists represent an overall return rate of 58%. There were no statistically significant differences in participation by gender, area of specialty, or years since dental school graduation. Eleven dentists from areas outside of the five regions completed this survey but are not included in the following analyses. We present data from the 534 practitioners who reported treating patients of ages 18 years or older in their practices. Participating dentists responded to overall patient care for the practice, so percentages include services provided by all the practice’s staff, including dental hygienists. A table of demographic and practice variables for the sample and each region are available at www.dpbrn.org/uploadeddocs/Table.adult.prevention.pdf. The sample is also described in Riley et al (21).

Measures

The questionnaire asked about the percentage of patients at least 18 years old that received dental sealants on the occlusal surfaces, were recommend a non-prescription (over-the-counter) fluoride rinse, provided a prescription for some form of fluoride, recommend an at-home regimen of chlorhexidine rinse, recommend sugarless or xylitol chewing gum.

The dentists also provided information about the race/ethnicity and of their patients, and the percent of patients that used dental insurance, public insurance, and self-payment. In addition, the following practice variables were recorded. The days a new patient has to wait for a new patient examination appointment and a treatment procedure appointment. The percent of overall practice time spent on non-implant restorations. Whether the dentist performs caries risk assessment for individual patients. The percentage of patients who are interested in individualized preventive treatment and the percent of patients who receive individualized preventive treatment.

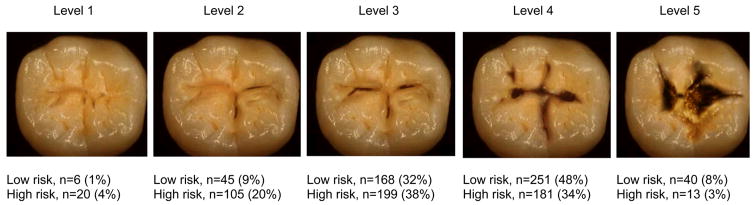

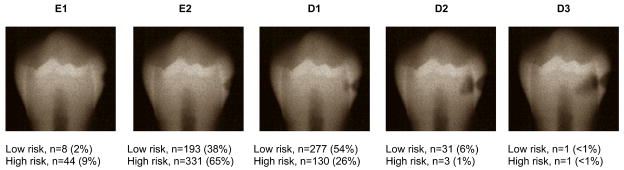

Dentists were asked to select the treatment codes they would recommend for each clinical scenario described as follows: The patient is a 30-year old female with no relevant medical history. These figures are presented in Espelid et al (22) and available at www.dbprn.org/uploadeddocs/Figure.occlusal.lesion.pdf and www.dpbrn.org/uploadeddocs/Figure.interproximal.lesion.pdf. She has no complaints and is in your office today for a routine visit. She has attended your practice on a regular basis for the past 6 years. Low-risk scenario: She has no other restorations than the one shown, no dental caries, and is not missing any teeth. High-risk scenario: She has 12 teeth with existing dental restorations, heavy plaque and calculus, multiple Class V white spot lesions, and is missing 5 teeth.

The dependent variable for the occlusal lesion examples were at which level of lesion severity (level 1=1, level 2=2, etc.) the dentist would first select to restore the occlusal lesion case for both low- and high-risk patient scenarios rather than preventive therapy. The dependent variable for interproximal lesion examples was the lesion depth, E1=1 (outer one-half of the enamel), E2=2 (inner one-half of the enamel), D1=3 (outer one-third of the dentin); D2=4 (middle one-third of the dentin), and D3=5 (inner one-third of the dentin) at which the dentist would first choose to do a permanent restoration, judging from the radiographic image of the given proximal surface, instead of only doing preventive therapy for the two risk scenarios. These four variables (occlusal lesion/low-risk scenario; occlusal lesion/high-risk scenario; interproximal lesion/low-risk; interproximal lesion/high-risk) reflect a treatment continuum based in lesion severity/depth which we refer to as the “lesion index”. A lower lesion index means that the dentist intervenes surgically on lesions of less depth. In addition, we calculated a “risk index” where the level of restorative intervention for the higher-risk patient scenario was subtracted from low-risk scenarios for both the occlusal lesion and proximal lesion. This variable reflects a change in the treatment continuum based on patient risk. A positive number indicates a later restoration on the low risk patient (conservative strategy), 0 would reflect no change, and a negative number would indicate an earlier restoration and a more-aggressive treatment strategy.

Statistical methods

The percentages for each caries prevention agent were coded to the categories’ medians to maintain the interval nature of the data so that parametric statistics could be used: 0%=0%, 1–24%=12.5%, 25–49%=37%, 50–74%=62%, 75–99%=87%, 100%=100%.

Correlation coefficients were calculated between dentist, patient, and practice characteristics and the frequency of use for each preventive agent. Variables with significant associations at p. < .05 were entered in a regression model as predictors of the frequency of use for that preventive agent (the dependent variable). In the first step, a region variable (US regions vs. SK region) was entered to adjust for potentially different preventive orientation of European dentists (23). The second step tested dentist, patient, and practice characteristics as predictors of the use of each preventive agent. In the third step, frequencies of the other preventive agents were entered to test for associations between agents. Associations between clinical scenarios indices and the frequency of use for each preventive agent were also tested using multiple regression.

To identify subgroups of dentists with a similar preventive orientation, a hierarchal clustering procedure was used. The sugarless or xylitol gum variable was not included as it was considered an adjunctive rather than a primary prevention agent. Ward’s clustering method with squared Euclidean distances as the similarity measure was chosen in order to be sensitive to differences in elevation as well as profile shape (24). The dentist, patient, and practice characteristics were tested for differences across the preventive clusters using ANOVA or chi-square as appropriate. Pair-wise comparisons were performed using a Bonferroni correction.

Results

Frequency of caries prevention techniques

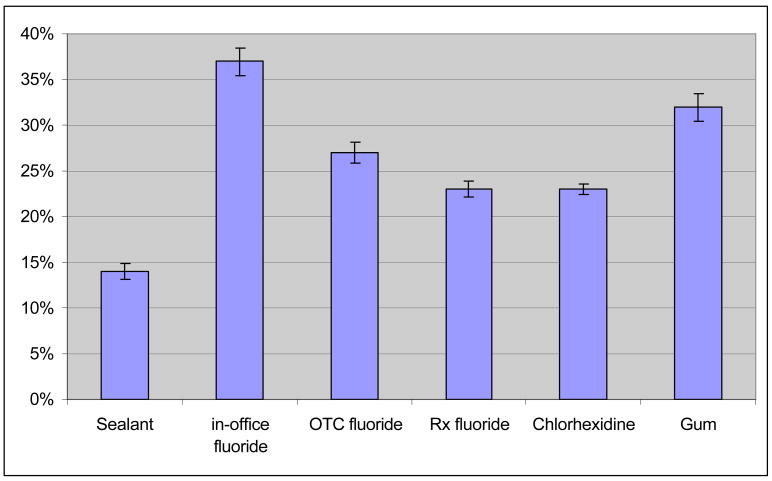

Figure 1 presents the use of preventive techniques by network dentists.

Figure 1. Frequency of use of preventive techniques by network dentists overall.

Key: OTC = over-the-counter, Rx = prescription. All agents were significantly different from each other with the exception of prescription fluoride and chlorhexidine which were not different.

Dentist, patient, and practice characteristics

Multivariate regression coefficients for the practice pattern variables (dentist, patient, and practice characteristics) that were significant at the bivariate level are presented for each of the caries preventive agents in Table 1. Significant associations with the frequency of use of other caries preventive agents tested in the third step of the regression models are also reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Multivariate regression coefficients for dentist, patient, and practice characteristics associated with specific caries prevention agents

| Predictor variables | B (SE) | Sig. |

|---|---|---|

| Sealant (model F = 8.074, p < .001) | ||

| Patients 0–17 years of age | 1.604 (.505) | .002 |

| Percent of patients of Hispanic ethnicity | 2.89 (1.06) | .007 |

| Patient contact time spent on restoration procedures | −.646 (.437) | .140 |

| Patients that receive individual caries prevention | .040 (.026) | .121 |

| Practice caries risk assessment | 4.217 (1.910) | .028 |

| In-office fluoride | .1412 (.024) | < .001 |

| In-office fluoride (model F = 9.252, p < .001) | ||

| Patients 0–17 years of age | 3.229 (.817) | <.001 |

| Patients with private dental insurance | 1.315 (.660) | .049 |

| Days wait for new patient examination | .250 (.110) | .015 |

| Patient contact time spent on restoration procedures | −1.346 (.788) | .088 |

| Patients that receive individual caries prevention | .117 (.046) | .012 |

| Dental sealant | .463 (.080) | < .001 |

| Non-prescription fluoride | .163 (.061) | .008 |

| Non-prescription fluoride (model F = 8.927, p = .001) | ||

| Gender (female) | 5.916 (3.009) | .021 |

| Years of dental practice | −.220 (.114) | .049 |

| Patients 0–17 years of age | 1.426 (.637) | .026 |

| Patient contact time spent in restoration procedures | −1.479 (.584) | .012 |

| Patients that receive individual caries prevention | .135 (.035) | <.001 |

| In-office fluoride | .087 (.034) | .012 |

| Sugarless or Xylitol gum | .155 (.032) | < .001 |

| Prescription fluoride (model F = 4.287, p < .001) | ||

| Gender (female) | 5.302 (2.562) | .039 |

| Years of dental practice | −.199 (.095) | .036 |

| Dentist is of Hispanic ethnicity | −2.044 (.620) | .001 |

| Patients 0–17 years of age | −.919 (.529) | .088 |

| Caries risk assessment | 2.931 (1.487) | .044 |

| Patient contact time spent in restoration procedures | −1.479 (.584) | .012 |

| Patients that receive individual caries prevention | ..065 (.029) | .026 |

| In-office fluoride | .161 (.028) | < .001 |

| Non-prescription fluoride | .087 (.038) | .022 |

| Chlorhexidine rinse | .315 (.063) | < .001 |

| Chlorhexidine rinse (model F = 10.625, p < .001) | ||

| Years of dental practice | −.199 (.063) | .002 |

| Patient contact time spent in restoration procedures | −1.506 (.327) | < .001 |

| Number of dental chairs in practice | .139 (.026) | < .001 |

| Full-time status | −3.063 (1.873) | .103 |

| Patients what desire individual caries prevention | .043 (.027) | .115 |

| Patients that receive individual caries prevention | .060 (.024) | .013 |

| Prescription fluoride | .168 (.029) | < .001 |

| Sugarless or Xylitol chewing gum (model F = 7.776, p < .001) | ||

| Dentist is of Hispanic ethnicity | 2.653 (1.025) | .010 |

| Number of patients seen each week | .106 (.055) | .055 |

| Patients that receive individual caries prevention | .227 (1.215) | < .001 |

| In office-fluoride | .204 (.046) | < .001 |

| Non-prescription fluoride | .261 (.060) | < .001 |

Practice of caries risk assessment; no=0, yes=1.

Dentist gender male=0, female=1.

Caries risk assessment; do not practice=0, practice caries risk assessment practiced for individual patients=1

Full-time status; part-time=0, full-time=1

Case scenarios

The percentages of dentists who chose to restore at each level (lesion index) by patient risk scenario for the occlusal or proximal lesions are presented in Figures 2 and 3. The occlusal risk index indicated that 187 (36%) dentists would restore later on the lower-risk patient, 322 (60%) would restore at the same level of caries development, and 13 (3%) would restore the low-risk patient at an earlier stage. The proximal risk index indicated that 236 (47%) dentists would restore later on the low-risk patient, 269 (53%) at the same level of caries development, and 2 (<1%) would restore at an earlier stage. For further analysis, dentists who would restore at an earlier stage or the same stage in the low-risk patient were combined and compared to dentists who took a more-conservative approach and delayed restoration with the lower-risk patient. We interpret this variable to reflect a dentist whose treatment decisions were not and were influenced by risk.

Figure 2. Case for occlusal lesion.

(Reprinted from Espelid et al45 with permission)

This figure will be posted at www.dpbrn.org/uploadeddocs/Figure.occlusal.lesion.pdf

Figure 3. Case for interproximal lesion.

(Reprinted from Espelid et al45 with permission)

This figure will be posted at www.dpbrn.org/uploadeddocs/Figure.interproximal.lesion.pdf

Restoration at a later level of development (lesion index) for the occlusal high-risk and occlusal low-risk patients were each associated with greater use of several preventive agents (Table 2). The interproximal lesion index was associated with non-prescription fluoride for the low-risk scenario, but the interproximal lesion index was not associated with use of any of the preventive agents.

Table 2.

Multivariate regression coefficients for case scenarios and use of preventive agents

| B (SE) | Sig | B (SE) | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All dentists (n=535) | |||||

| Occlusal lesion index, low-risk scenario (n=522) | Occlusal lesion index, high-risk scenario (n=527) | ||||

| Dental sealant | 2.139 (1.230) | .083 | Dental sealant | 2.845 (1.081) | .009 |

| In-office fluoride | 4.975 (1.870) | .008 | In-office fluoride | 4.370 (1.993) | .029 |

| Non-prescription fluoride | 2.661 (1.647) | .107 | Non-prescription fluoride | 3.739 (1.449) | .010 |

| Chlorhexidine | 2.776 (1.195) | .021 | |||

| Proximal lesion index, low-risk scenario (n=508) | Proximal lesion index, high-risk scenario (n=507) | ||||

| Non-prescription fluoride | 3.608 (2.108) | .088 | none significant | ||

| Dentists who assess caries risk (n=370) | |||||

| Occlusal lesion index, low-risk scenario (n=356) | Occlusal lesion index, high-risk scenario (n=360) | ||||

| In-office fluoride | 2.166 (1.249) | .084 | In-office fluoride | 4.530 (2.248) | .042 |

| Non-prescription fluoride | 4.613 (2.201) | .037 | Non-prescription fluoride | 5.730 (1.896) | .003 |

| Prescription fluoride | 3.455 (1.523) | .024 | |||

| Proximal lesion index, low-risk scenario (n=350) | Proximal lesion index, high-risk scenario (n=348) | ||||

| Non-prescription fluoride | 7.827 (2.775) | .005 | none significant | ||

| Dentist who do not assess caries risk (n=163) | |||||

| Occlusal lesion index, low-risk scenario (n=152) | Occlusal lesion index, high-risk scenario (n=156) | ||||

| none significant | Dental sealant | 5.198 (1.933) | .008 | ||

| Proximal lesion index, low-risk scenario (n=158) | Proximal lesion index, high-risk scenario (n=159) | ||||

| none significant | none significant | ||||

Sample size differs because some dentists failed to provide some responses to the clinical scenarios. The region variable was used as a covariate in all analyses. Gender and years since graduation were also used as covariates for analyses involving non-prescription and prescription fluoride because of significant associations with the frequency of recommendation for these agents.

We then divided the sample into dentists who reported performing caries risk assessment on their patients (n = 376, 69%) and those who do not (n = 170, 31%) and repeated these analyses. Among dentists who perform caries risk assessment, the lesion index (restoration at a later level of development–more-conservative treatment) for the occlusal lesion in the low-risk scenario was associated with greater use of in-office fluoride and non-prescription fluoride. The occlusal lesion index for the high-risk scenario was associated with greater use of in-office fluoride, non-prescription fluoride, and prescription fluoride. The lesion index for the proximal lesion in the low-risk scenario was associated with greater use of in-office fluoride) and non-prescription fluoride. The lesion index for the proximal lesion in the high-risk scenario was not associated with use of any of the preventive agents.

Among dentists who do not assess caries risk, the occlusal lesion index in the high-risk scenario was associated with greater use of dental sealant. The other three scenarios were not associated with use of any of the preventive agents.

The occlusal risk and interproximal risk indices (differences in treatment between high-and low-risk scenarios) were not associated with the use of any of the preventive agents.

Dentists grouped according to preventive profile

Ten dentists did not answer one or more of the prevention questions, consequently they were not classified. Inspection of the agglomeration coefficients from the cluster analysis showed that the percentage increase between the three-cluster and the two-cluster solutions was nearly three times the increase for the preceding steps. This suggests that the final three clusters are dissimilar and that the three-cluster solution is the most appropriate (25). Mean and SD for the five caries prevention agents for each of the three-cluster subgroups are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Use of preventive agents by preventive subgroups and differing dentist, patient, and practice characteristics.

| Selective users | Non-prescription fluoride preference | In-office fluoride preference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caries prevention (n=525) | N=339 | N=75 | N=111 |

| Dental sealant | 10%a | 18%b | 23%b |

| In office fluoride | 17%a | 48%b | 90%c |

| Non-prescription fluoride | 17%a | 75%b | 23%c |

| Prescription fluoride | 19%a | 23%b | 33%b |

| Chlorhexidine rinse | 16%a | 16% | 19%b |

| Practice characteristics | |||

| Gender (males) | 83%a | 72%b | 82%a |

| Patients 0–17 years of age (%) | 20a (SD=11) | 25 (SD=23) | 28b (SD=19) |

| Patients of White race (%) | 75a (SD=21) | 71 (SD=21) | 68b (SD=20) |

| Days wait for a new patient examination | 10.5a (SD=0.9) | 16.6b (SD=1.9) | 17.8b (SD=1.6) |

| Patients that desire individual caries prevention (%) | 37a (SD=15) | 47b (SD=32) | 45b (SD=28) |

| Patients that receive individual caries prevention (%) | 46a (SD=33) | 70b (SD=30) | 60b (SD=33) |

| Practice caries risk assessment | 64%a | 83%b | 70%b |

Key: Groups with different superscripts are different at p < .05. Subgroups did not differ on other practice characteristics.

The largest subgroup (n = 339) reported moderate use of caries prevention across all five treatment methods, ranging from 19% of adult patients receiving a prescription for fluoride to applying a dental sealant to 10% of their patients. No particular modality was favored and we labeled this group “selective users”. The second group consisted of 75 dentists who were markedly higher users of non-prescription fluoride (75% of their patients). This group was labeled “non-prescription fluoride preference”. The final group of 111 dentists reported high use of in-office fluoride on 90% of patients and was labeled “in-office fluoride preference”.

The preventive clusters differed on gender, the percentage of pediatric patients seen in their practices, patients of White race, number of days waiting for an examination appointment, patients that are provided individualized caries prevention, patients interested in individualized caries prevention, and assess caries risk for individual patients (Table 3).

In the case scenarios, the in-office fluoride preference group tended to delay a restoration longer than the other two groups based on the occlusal lesion index for the low-risk patient (selective users, P < .001; non-prescription fluoride preference, P =.047) and the high-risk patient (selective users, P = .001; non-prescription fluoride preference, P =.043).

Discussion

This was one of the first studies to examine dental practice patterns across a wide range of specific agents for caries prevention or management for adult patients. In-office applied topical fluoride was the most frequently used method of caries prevention; however, at-home applied fluoride regimen and chlorhexidine rinse were also frequently used. The most frequent users of caries prevention were recently-graduated dentists, those who regularly perform caries risk assessment, and dentists who practice individualized caries prevention. We also identified groups of dentist who shared a common preference for certain preventive agents.

Sealants

Dental sealants can be effective in preventing the progression of early non-cavitated carious lesions (4), even when sealing over existing bacteria (26). Consistent with this, recent guidelines developed by the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs have recommended the use of sealants for all age groups (2). Results from the current study suggest that dental sealants are an infrequent choice for caries prevention for adult patients among practicing dentists, and that potentially good adult candidates may not be receiving sealants.

The use of sealants was independent of the insurance variable. However, a study of children ages 12–14 found a significant increase in sealant treatment when fees were increased (27). Another study, again examining sealant use only for children, found that sealants were placed more often among general dentists with knowledge of the benefits and cost-effectiveness of sealants, dentists who had recently attended a continuing education course about prevention for children, and by the most-recent dental school graduates (12). We did not test in this current study whether the lack of knowledge of the evidence is associated with underuse of sealants. We were unable to find any other studies that have associated use of sealants in adults with dentist or practice characteristics.

Fluorides

Fluoride is an effective anti-caries agent and has been a major factor in the decline in the prevalence and severity of caries in most developed countries (6,28,29). In addition, persons at even moderate risk can benefit from adjunctive application of fluoride (30). Our finding that network dentists apply an in-office fluoride on 37% of their adult patients can be compared to a 2005 survey of Indiana dentists and hygienists by Yoder et al (10). They reported that 61% of dentists said they always or usually apply fluoride on adults with recent or active caries and 36% indicated always or usually using fluoride on patients without recent or active caries. Yoder did not ask about the use of other preventive agents.

Network dentists recommended a non-prescription fluoride or a prescription fluoride to about 1 in every 4 adult patients. Assuming that when an at-home fluoride is suggested, the dentist chooses one or the other, about 50% of adult patients would be sent home to apply some form of fluoride treatment. Only twenty dentists, representing less than 4% of the dentists sampled, reported they do not recommend the use of individually-applied fluoride to any of their adult patients (data not reported elsewhere). We presume that the majority of dentists made these recommendations based on perceived patient risk, as not all dentists reported assessing patient risk, and this study did not establish the level of patient risk within each practice.

Chlorhexidine

Chlorhexidine has been shown to reduce the levels of mutans streptococci in the plaque of human biofilm (31). We found that network dentists reported using chlorhexidine rinse on nearly 25% of adult patients and similar frequencies were found for the two at-home fluoride modalities. Use at this level suggests a relatively high acceptance by network dentists, particularly as chlorhexidine rinse has been specifically recommended for patients at high caries risk and those with low saliva rates (32). Using data collected in 1995, Fiset and Grembowski (33) found chlorhexidine was being used on adult patients in approximately 40% of the practices surveyed and had been adapted at similar rates to that of dental sealants. Our results suggest that current practice patterns involve greater use of chlorhexidine compared to dental sealants for adult patients. One potential drawback to a chlorhexidine rinse is the unpleasant taste. Because of this, chlorhexidine in its current form may be better suited for adults than children. This assertion is supported by a DPBRN finding that chlorhexidine was recommended more than twice as often for adults as children (34). Development of new delivery systems for chlorhexidine that improve patient compliance is needed (35)

Chewing gum

Chewing gum has important potential as a delivery vehicle for caries protective agents, as clinical trials have shown that chewing sugarless gum leads to substantial caries prevention, with xylitol-containing gums being particularly effective (36). We found that gum was the most often recommended preventive agent not applied in the dental office. In a review of the evidence for use of gum in caries control, Burt (37) emphasized that dentists should stress that chewing xylitol-sweetened gum is a supplemental practice, not a substitution for a preventive dental program.

Predictors of caries prevention

Clinical decisions between surgical intervention and a more-conservative approach that involves use of preventive agents are complex, but should be guided by the clinical examination and patient risk (38). We found that preventive agents were used most often by dentists who report that they practice risk assessment and use individualized prevention. This finding was validated by the case scenarios which showed that dentists who would delay restoration until a more-advanced lesion depth, used prevention with a higher frequency in their practices. This was further supported by additional analyses – limited to only those dentists who practice caries risk assessment - the frequency of sealant and fluoride use were highly associated with the conservative – aggressive caries management continuum. Only a single association was significant among dentists who do not perform caries risk assessment. Interestingly, the occlusal case scenario was more strongly associated with prevention than was the proximal case scenario. It should be noted that although dentists may report that they do not formally assess patients caries risk, findings from clinical examination may nevertheless be considered in decisions to treat according to different caries risk. A study among pediatric dentists has also found that dentists who assessed caries risk had a more-conservative restorative treatment approach (39). We found that the lesion index, based on lesion depth, was associated with the use of a number of preventive agents, whereas the risk index was not. This could be interpreted to suggest that dentists placed more weight in caries treatment decisions that are based on lesion depth than those based on patient risk. This assertion would require that the lesion and risk index were scaled equivalently, an assumption we could not test.

Other sources of variability in dentists’ decisions can be uncertainty of overall caries activity, whether the patient is seen regularly, differences in patients’ ability to pay for services, the patient’s understanding of caries as a disease, caries treatment philosophy learned in dental training, or community expectations for standards of care (17). We did not test the accuracy of caries activity assessment; however, we did find other dentist and practice variables associated with use of fluorides. There was some evidence to support the notion that dentists use prevention based on patients’ payment method. For example, in-office fluoride was administered by dentists when a higher percentage of patients have dental insurance and by dentists in busier practices. At the same time, patient-applied fluorides or a chlorhexidine rinse, where the dentist would not charge a fee for direct service, were not associated with these variables.

Other studies have also found that reimbursement increases the use of in-office administered fluorides by dentists. For example, one study found that the institution of payment for fluoride varnish increased the percent of dentists who use fluoride varnish regularly from 32% to 44% (40). Dentists’ use of chlorhexidine rinses and sealants for adults had not changed in that study, suggesting that the change was specific to fluorides. Another study found that patients most likely to receive topical fluoride were from high economic status areas; however, insurance status was not associated with fluoride use (41).

Among DPBRN practices, female dentists and more-recent graduates recommended prescription and non-prescription fluorides the most frequently. There are examples from medicine that demonstrate that female physicians show greater attention to preventive aspects of patient care (42). The literature on gender differences in prevention practices among dentists is mixed. A study of Australian dentists found higher rates of caries prevention used by female dentists (14). However, Atchison (43) did not find gender differences in services grouped into a single category of “sealants/fluoride varnish/topical varnishes”, which would be similar to combining our two questions – dental sealants and in-office fluoride. Brennan and Spencer (14) also found that younger dentists were the most frequent users of fluoride. These findings are consistent with the current emphasis by dental schools on more-conservative caries management (44,45). With the recent increase in the numbers of female dentists entering the workforce (46), these two factors may be confounded.

Preventive preference profiles

We found that provision of certain types of preventive care was associated with a higher likelihood of another modality being used by the same practitioner. A pattern of higher use was found for in-office fluoride, dental sealants, and providing a prescription fluoride, and between a prescription fluoride and chlorhexidine rinse. This would suggest that subsets of dentists have a certain preventive mindset, and consequently use or recommend these specific preventive agents often.

Common patterns of prevention among groups of dentists were also identified using cluster analysis. This unique approach to testing for preventive profiles is a descriptive tool that forms clusters of dentist who have used preventive modalities in similar frequencies. With this technique we found three homogenous groups who differed across several of the dentist, patient, and practice variables differed across the groups, validating their differences. Of note was the group of selective users who were the least likely to assess caries risk or have patients interested in individualized caries prevention. It is not clear whether patients of selective users were not interested in individualized prevention before becoming a patient, or because of influences of their particular dentist. In addition, the in-office fluoride preference group tended to make the most conservative restoration decisions on some of the case scenarios.

We remind the reader that the measures of prevention were self-reported, and are subject to both social desirability and recall bias. A recently published study has compared self-report with chart review and direct observation and concluded that dental practitioner self-reports of treatment over-stated the services provided (47). However, preventive services were among the most accurately reported. Additionally, the study sample is not a random sample of general dentists. Consequently, the extent to which these findings generalize to this population cannot be stated with certainty.

Conclusion

These results indicate that caries preventive agents are commonly used for adults by many of the network dentists. These dentists tended to be younger and more likely to have busy practices with patients with private dental insurance. However, our finding of a group of dentists that only uses preventive agents selectively and was the least likely to report using caries risk assessment would suggest that some dentists’ current treatment lags what is currently considered to be best practice based on recent scientific evidence. Cooperation between PBRNs, organized dentistry, and dental education entities will be important in communicating recent research findings to foster movement of the latest scientific evidence into daily clinical practice by all dental care providers.

Table 4.

Demographics for participating DPBRN dentists.

This table will be posted at www.dpbrn.org/uploadeddocs/Table.adult.prevention.pdf

| Private practice | Large group practice | Public health | Males % (n) | Yrs practice Mean (SD) | Full time* % (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL/MS (n=302) | 99% (n=299) | ----- | 1% (n=3) | 85% (n=258) | 24.2 (10.4) | 87% (n = 260) |

| FL/GA (n=102) | 98% (n=100) | ----- | 2% (n=2) | 87% (n=88) | 25.0 (10.2) | 90% (n = 90) |

| MN (n=31) | 13% (n=4) | 87% (n=27) | ----- | 68% (n=21) | 19.4 (9.2) | 80% (n = 24) |

| PDA (n=49) | ----- | 100% (n=49) | ----- | 82% (n=40) | 17.4 (9.6) | 86% (n = 42) |

| SK (n=50) | 58% (n=29) | ----- | 42% (n=21) | 52% (n=26) | 20.7 (11.3) | 69% (n = 31) |

| Total (n=534) | 81% (n=432) | 14% (n=76) | 5% (n=26) | 81% (n=435) | 23.8 (10.2) | 86% (n=438) |

Note.

works >32 hours per week.

Practices were characterized by “type of practice”, for which we categorized each dentist as being in either: (1) a solo or small group private practice (SPP); (2) a large group practice (LGP); or (3) a public health practice (PHP). “Small” practices were defined as those that had 3 or fewer dentists. Public health practices were defined as those that receive the majority of their funding from public sources.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by NIH grants DE-16746 and DE-16747. Persons who comprise the DPBRN Collaborative Group are listed at http://www.DPBRN.org/users/publications. Opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as necessarily representing the views of the respective organizations or the National Institutes of Health. The informed consent of all human subjects who participated in this investigation was obtained after the nature of the procedures had been explained fully.

Contributor Information

Joseph L. Riley, III, Associate Professor, Department of Community Dentistry and Behavioral Science, College of Dentistry, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA.

Valeria V. Gordan, Professor, Department of Operative Dentistry, College of Dentistry, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA.

D. Brad Rindal, Investigator and Dental Health Provider, HealthPartners, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Jeffrey L. Fellows, Investigator, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Craig T. Ajmo, Private practitioner in Dunedin, Florida, USA.

Craig Amundson, HealthPartners Central Minnesota Clinics, St. Cloud, Minnesota, USA.

Gerald A. Anderson, Private practitioner in Selma, Alabama, USA.

Gregg H. Gilbert, Professor and Chair, Department of General Dental Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

References

- 1.Bader JD, Shugars DA, Bonito AJ. A systematic review of selected caries prevention and management methods. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29(6):399–411. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beauchamp J, Caufield PW, Crall JJ, et al. Evidence-based clinical recommendations for the use of pit-and fissure sealants: a report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:257–26. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Logan S, Sheiham A. Systematic review of controlled trials on the effectiveness of fluoride gels for the prevention of dental caries in children. J Dent Educ. 2003;67(4):448–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffin SO, Regnier E, Griffin PM, Huntley V. Effectiveness of fluoride in preventing caries in adults. J Dent Res. 2007;86(5):410–5. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mjör IA, Holst D, Eriksen HM. Caries and restoration prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(5):565–70. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. MMWR. 2001;50:1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bader JD, Shugars DA. The evidence supporting alternative management strategies for early occlusal caries and suspected occlusal dentinal caries. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2006;6(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helminen SK, Vehkalahti MM. Does caries prevention correspond to caries status and orthodontic care in 0- to 18-year-olds in the free public dental service? Acta Odontol Scand. 2003;61(1):29–33. doi: 10.1080/ode.61.1.29.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegal MD, Garcia AI, Kandray DP, Giljahn LK. The use of dental sealants by Ohio dentists. J Public Health Dent. 1996 Winter;56(1):12–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoder, Yorty JS, Brown KB, et al. Caries risk assessment/treatment programs in U.S. dental schools. J Dent Educ. 1999;63(10):745–7. 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark DC, Berkowitz J. The relationship between the number of sound, decayed, and filled permanent tooth surfaces and the number of sealed surfaces in children and adolescents. J Public Health Dent. 1997 Summer;57(3):171–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1997.tb02969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Main PA, Lewis DW, Hawkins RJ. A survey of general dentists in Ontario, Part I: Sealant use and knowledge. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997 Jul-Aug;63(7):542, 545–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bader JD, Shugars DA. Variation, treatment outcomes, and practice guidelines in dental practice. J Dent Educ. 1995;59:61–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan DS, Spencer AJ. The role of dentist, practice and patient factors in the provision of dental services. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(3):181–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Traebert J, Marcenes W, Kreutz JV, Oliveira R, Piazza CH, Peres MA. Brazilian dentists’ restorative treatment decisions. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2005;3(1):53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Rindal DB, Pihlstrom DJ, Benjamin PL, Wallace MC DPBRN Collaborative Group. The creation and development of the dental practice-based research network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(1):74–81. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anusavice KJ. Present and future approaches for the control of caries. J Dent Educ. 2005;69(5):538–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert GH, Bader JD, Litaker MS, Shelton BJ, Duncan RP. Patient-level and practice level characteristics associated with receipt of preventive dental services: 48-month incidence. J Public Health Dent. 2008;68(4):209–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, Benjamin PL, Richman JS, Pihlstrom DJ DPBRN Collaborative Group. Dentists in practice-based research networks have much in common with dentists at large: evidence from The Dental PBRN. Gen Dent. 2009;57(3):270–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, Benjamin PL, Richman JS, Pihlstrom DJ, Qvist V DPBRN Collaborative Group. Practices participating in a dental PBRN have substantial and advantageous diversity even though as a group they have much in common with dentists at large. BMC Oral Health. 2009;159:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riley JL, Richman JS, Rindal DB, Fellows JL, Qvist V, Gilbert GH, Gordon VV. Use of caries prevention agents in children: findings from The Dental Practice-based Research Network. In press at Oral Health and Preventive Dentistry. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espelid I, Tveit AB, Mejáre I, Nyvad B. Caries - New knowledge or old truths? The Norwegian Dental Journal. 1997;107:66–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burt BA. Prevention policies in the light of the changed distribution of dental caries. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56(3):179–86. doi: 10.1080/000163598422956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Overall JE, Gibson JM, Novy DM. Population recovery capabilities of 35 cluster analysis methods. J Clin Psychol. 1993;49(4):459–70. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199307)49:4<459::aid-jclp2270490402>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milligan GA, Cooper MC. An examination of procedures for determining the number of clusters in a data set. Psychometrika. 1967;50:159–79. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oong EM, Griffin SO, Kohn WG, Gooch BF, Caufield PW. The effect of dental sealants on bacteria levels in caries lesions: a review of the evidence. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(3):271–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarkson JE, Turner S, Grimshaw JM, Ramsay CR, Johnston M, Scott A, Bonetti D, Tilley CJ, Maclennan G, Ibbetson R, Macpherson LM, Pitts NB. Changing clinicians’ behavior: a randomized controlled trial of fees and education. J Dent Res. 2008;87(7):640–4. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burt BA. Prevention policies in the light of the changed distribution of dental caries. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56(3):179–86. doi: 10.1080/000163598422956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Featherstone JD. The science and practice of caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131(7):887–99. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Professionally applied topical fluoride: evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(8):1151–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Autio-Gold J. The role of chlorhexidine in caries prevention. Oper Dent. 2008;33(6):710–6. doi: 10.2341/08-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anusavice KJ. Chlorhexidine, fluoride varnish, and xylitol chewing gum: underutilized preventive therapies? Gen Dent. 1998;46(1):34–8. 40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiset L, Grembowski D. Adoption of innovative caries-control services in dental practice: a survey of Washington state dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:337–45. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riley JL, Rindal DB, Fellows JL, Williams OD, Gilbert GH, Gordon VV. Use of caries preventive agents on adult patients compared to pediatric patients by general practitioners: findings from The Dental PBRN. In press at J Am Dent Assoc [Google Scholar]

- 35.Featherstone JD. Delivery challenges for fluoride, chlorhexidine and xylitol. BMC Oral Health. 2006;15(6 Suppl 1):S8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maguire A, Rugg-Gunn AJ. Xylitol and caries prevention--is it a magic bullet? Br Dent J. 2003;194(8):429–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4810022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burt BA. The use of sorbitol- and xylitol-sweetened chewing gum in caries control. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(2):190–6. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young DA, Featherstone JD, Roth JR, Anderson M, Autio-Gold J, Christensen GJ, Fontana M, Kutsch VK, Peters MC, Simonsen RJ, Wolff MS. Caries management by risk assessment: implementation guidelines. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35(11):799–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de la Cruz GG, Rozier RG, Slade G. Dental screening and referral of young children by pediatric primary case providers. Pediatrics. 2004;114:642–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiset L, Grembowski D, Del Aguila M. Third-party reimbursement and use of fluoride varnish in adults among general dentists in Washington State. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131(7):961–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brennan DS, Spencer AJ. Service patterns associated with coronal caries in private general dental practice. J Dent. 2007;35(7):570–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas RK. The feminization of American medicine. Mkt Hlth Svcs. 2000;20(3):13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atchison KA, Bibb CA, Lefever KH, Mito RS, Lin S, Engelhardt R. Gender differences in career and practice patterns of PGD-trained dentists. J Dent Educ. 2002 Dec;66(12):1358–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yorty JS, Brown KB. Caries risk assessment/treatment programs in U.S. dental schools. J Dent Educ. 1999 Oct;63(10):745–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown JP. A new curriculum framework for clinical prevention and population health, with a review of clinical caries prevention teaching in U.S. and Canadian dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(5):572–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.del Aguila del Aguila MA, Leggott PJ, Robertson PB, Porterfield DL, Felber GD. Practice patterns among male and female general dentists in a Washington State population. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005 Jun;136(6):790–6. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demko CA, Victoroff KZ, Wotman S. Concordance of chart and billing data with direct observation in dental practice. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008 Oct;36(5):466–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]