Abstract

High-throughput (HT) methodologies have had a tremendous impact on structural biology of soluble proteins. High-resolution structure determination relies on the ability of the macromolecule to form ordered crystals that diffract X-rays. While crystallization remains somewhat empirical, for a given protein, success is proportional to the number of conditions screened and to the number of variants trialed. HT techniques have greatly increased the number of targets that can be trialed and the rate at which these can be produced. In terms of number of structures solved, membrane proteins appear to be lagging many years behind their soluble counterparts. Likewise, HT methodologies for production and characterization of these hydrophobic macromolecules are only now emerging. Presented here is an HT platform designed exclusively for membrane proteins that has processed over 5000 targets.

Keywords: Membrane proteins, detergent, expression, high-throughput, structure, structural genomics

Introduction

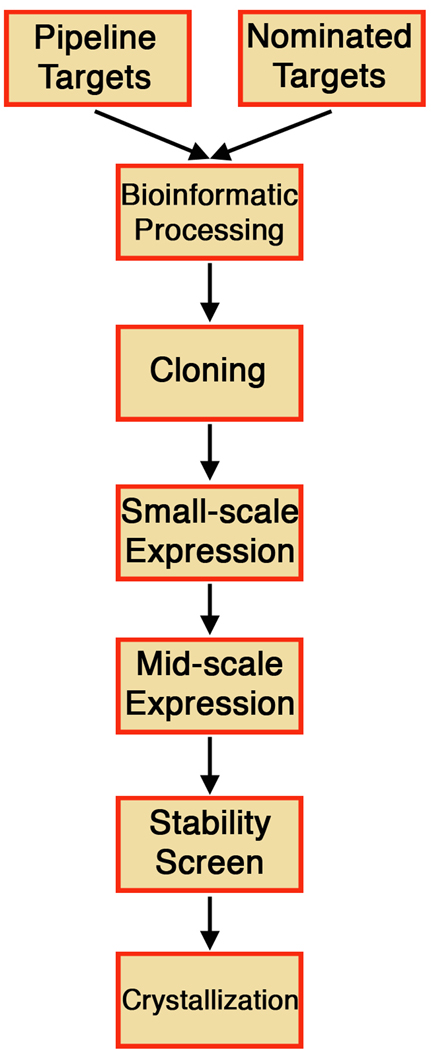

Every biological process requiring exchange of information between cells or intracellular compartments or detection of and response to either extracellular stimuli or cues or nutrients, relies for success on one or more proteins embedded in the cell membranes and endowed with the capability of accurately carrying out such task. Membrane proteins comprise approximately 30% of all proteins in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms [1], and, not surprisingly, represent by far the most thought-after pharmacological targets. However, despite their importance, they are but a fraction of a percent of those with a known structure. As of December 2009, 214 unique entries in the protein data bank (PDB; [2]), only 0.5% of the total, were accounted for by membrane-spanning proteins. Indeed, integral membrane proteins present formidable, albeit not insurmountable, challenges for structural analysis. The field has progressed tremendously since the first result in three dimensions, by electron crystallography at 7Å, on bacteriorhodopsin [3] and the first high resolution structure, at 3Å by x-ray crystallography on a photosynthetic reaction center [4], and membrane protein structures have been determined at an accelerated pace in recent years. Nevertheless, structural output for this class of macromolecules remains negligible in comparison to their soluble counterparts. The initial objective of the New York Consortium of Membrane Protein Structure (NYCOMPS) was to construct an automated HT pipeline for integral membrane protein production and preliminary characterization that would achieve a comparable level of productivity to that observed for soluble proteins in the initial phases of the Protein Structure Initiative (PSI). To fulfill this goal, we designed and implemented a centralized Protein Production Facility at the New York Structural Biology Center (NYSBC) to implement cloning and screening activities. The methodologies underpinning this pipeline, presented in detail below and in schematic form in Figure 1, were developed over a period of years through iterative rounds of testing and optimization and have so far resulted in ~7,000 cloned and screened targets, yielding crystals from ~30 of these, and 24 structures from 6 unique novel membrane protein.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the NYCOMPS HT pipeline for the identification of prokaryotic membrane proteins suitable for structural studies.

Overview of the field

The natural association of membrane proteins with lipid bilayers, and the resulting need of detergents for extraction and purification complicate their structural analysis. Once diffracting membrane-protein crystals are obtained, for example, the diffraction analysis is typically as straightforward as it is for aqueous soluble macromolecules. Problems that arise in the recombinant expression of membrane proteins are even more limiting than difficulties in purification and crystallization. Furthermore, the establishment of a suitable recombinant expression system is typically a prerequisite for successful structure determination, and represents the first bottleneck of the entire process [5]. There are only few examples present in high-abundance from natural sources, and membrane proteins are most often intolerant to standard, non-affinity based purification methods such as ion exchange and hydrophobic interaction chromatography. Membrane proteins have the tendency to perform poorly in ectopic expression systems [5]. This may be caused by a series of reasons, including toxicity of the foreign protein to the host, specific requirements or differences in the translocation, membrane insertion machinery or in the lipid composition of the membranes [6], and possibly the limited amount of free surface available for packing large amounts of recombinant protein. The situation is further aggravated for eukaryotic membrane proteins, given the complexity of the milieu in which they evolved, and their frequent need for chaperones, for specific lipids and for precise post-translational modifications such as glycosylation, sulfonation, palmitoylation and other covalent modifications [6, 7]. In addition, post-translational modifications add possible heterogeneity to the sample, which may hinder downstream crystallization success. Typically, prokaryotic membrane proteins are expressed in E. coli, although systems based on Lactococcus lactis have been developed and successfully employed [8]. The success of E. coli is due to the fact that it is robust, economical, well-understood, readily expandable, and easily manipulated for labeling of selected amino acids (such as methionine with selenium for phasing of diffraction data from crystals [9]). Eukaryotic counterparts, with notable exceptions [5, 6, 10], are dependent for their successful expression on matching or similarly complex systems such as yeast, baculovirus-infected insect cells and mammalian cells [7, 11]. In general, eukaryotic membrane proteins have been recalcitrant in expression at the scale needed for structural analysis [6], although high-resolution structures from recombinant sources are finally emerging at a much-needed accelerating pace (for examples, see [12–17]).

Choice and optimization of a suitable expression system are by no means the only requirements for successful structure determination of a membrane protein. Detergents and their micelles are notorious poor substitutes of lipids and their bilayer structures, often leading to destabilization, denaturation and aggregation [18]. Unfortunately, detergents are required to extract and purify the target protein. The choice of detergent is a key parameter of the entire process, further complicated by the fact that the shorter the aliphatic chain of the detergent, the more destabilizing the effect on the protein but the better becomes the probability of crystallization and x-ray diffraction to high resolution. Furthermore, a detergent required for high yield extraction may not be optimal in preserving functionality or oligomeric state, and may also have a detrimental impact on crystallization [18]. Therefore, different detergents may be required for the various, distinct phases of the necessary processes leading to structure determination. Extensive screening and optimization steps are thus required. These tedious procedures are time consuming and expensive due the cost of reagents, and the success rate is inevitably low.

How can the probability of success for membrane protein structures be maximized? Following a conventional approach, one could envision optimizing expression, extraction and purification conditions in a tailor-made approach to maximize yields and stability of the given protein, without any or with minimal intervention on the gene. Structures of membrane proteins isolated from natural sources are inevitably confined to being pursued by this approach. Alternatively, the expression and purification protocols can be fixed, and genetic variants of a protein of interest cloned and screened to select the subset bearing the highest probability of crystallization. Here, expression conditions are set to maximize yields, and chosen based on experience and consensus. Purification parameters are defined to select expressing proteins that abide to one or more characteristics thought to be indicative, suggestive of or necessary for successful crystallization. These include, for example, a sharp elution profile from size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), or stability in a short-chain detergent [19].

Homology screening is a powerful approach, and is the basis of many structural genomics initiatives. Homologues provide natural variation that may be less toxic, better expressed, more stable (particularly in short chain detergents) and may even be more likely to crystallize. Screening can also be performed on synthetic variants, such as mutants with the goal of selecting those with enhanced properties like expression levels and thermal stability [20, 21].

A high-throughput (HT) screening platform is essential for this approach to succeed. For soluble proteins, this has been achieved, and suitable robust platforms extensively tested, and thoroughly optimized, leading to the determination of thousands of high-resolution structures [22, 23]. Furthermore, technologies developed by structural genomics centers have also been invaluable to the community at large, and on average, costs associated with every structure determination have dropped dramatically [24]. In the use of HT methodologies, membrane proteins are once again lagging behind their soluble counterparts. However, several reports on every stage of the process have facilitated the design of platforms and the adaptation of HT techniques for membrane protein cloning, expression screening and purification.

In an excellent review of collective methods used in the expression and purification of over 10,000 soluble proteins [25], a set of consensus protocols were presented and some of these procedures could be adaptable to the HT production of membrane proteins. This is particularly true for the initial cloning steps, where ligation-independent cloning (LIC; [26]) is very useful as it is rapid, economical, efficient, it requires no restriction digestion of the PCR-amplified product, and also can be designed to include no additional amino acids in the transcript. LIC has been successfully used for largescale membrane protein cloning efforts [27].

For HT expression, the consensus points to E. coli being the preferred host for prokaryotic proteins, although Lactococcus lactis [8] and cell-free systems and have also been proposed [28, 29]. Economical small-scale incubators have been developed that are useful for high-density growth of E. coli in deep-well blocks. Optical densities measured at 600nm approaching 10 units are possible with just 600µL of culture [30]. Cultures grown under these conditions appear also to be scalable with growth in both specialized 96-tube airlift fermenters [31] and ultraflasks [32].

Determination of optimal expression, extraction, and purification parameters has been the focus of several studies on varying numbers of membrane protein targets, ranging from several tens to few hundreds. In two manuscrips, Dobrovetsky et al. outline a HT process for membrane protein expression utilizing a single affinity tag and promoter system, one extraction and purification detergent followed by ion-exchange chromatography or SEC as a final purification step [33, 34]. Using these techniques they were able to screen 280 E. coli and Thermotoga maritima integral membrane proteins. The authors conclude that, in a manner analogous to the techniques involved in HT platforms for soluble proteins, similar approaches for membrane proteins will succeed, but with higher attrition rates. Lewinson et al. investigate many of the necessary parameters necessary of a structural genomics type approach to the production of membrane proteins [35], focusing on the prokaryotic P-type transporter family [36]. The authors set out to express and purify multiple homologues, in multiple strains, temperatures, affinity tags, promoters and extraction and purification detergents. They find that many factors appear to impact the final outcome, but conclude that i) the closer phylum of the target gene to the expression host, the better the possible outcome; ii) the promoter may affect the amount of protein produced and the membrane incorporation levels; iii) the position and nature of the affinity tag may have a profound impact on expression levels; iv) that only a small subset of extraction detergents results in a high percentage of success in solubilizing a majority of the membrane proteins, with n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM) being the most favored. In a similar study by Eshaghi et al., the expression profile of 49 E. coli membrane proteins was analyzed in this host varying, tag position, expression strain and extraction detergent [37]. Gateway [38] was utilized for the cloning, which may not be ideal for structural studies due to the introduction of additional amino acids at the protein termini. These parameters were assessed for success by dot blot and gel filtration analysis of some of the targets. The authors show that many assays can be conducted in a multi-well plate assay, and hence a high throughput may be achieved. The authors also settled on Fos-choline 12 (FC-12) as their standard extraction detergent, due to its good solubilization properties. However, care should be used before considering the Fos-choline detergents as the panacea for membrane protein studies, because it’s suitability as a crystallization detergent has yet to be widely accepted [39]. Indeed, a review of all membrane protein structures deposited in the PDB suggests that a majority of targets are solubilized in just a small subset of detergents, with DDM being the most commonly used for extraction and purification [40]. The same review also concludes that for recombinant proteins poly-histidines are the most commonly used engineered-affinity tags, and that in ~50% of the cases, SEC is employed as the final purification step.

Whilst a single, monodisperse elution peak from SEC does not guarantee success, this technique is a very informative, predictive method for likelihood of crystallization of membrane proteins [41], as it is for soluble proteins [39]. The elution profile of a membrane protein from a SEC column equilibrated in a given detergent can provide a reliable estimate on their aggregation state, and, in general, on their “well-being” in that surfactant. SEC can be readily adapted to HT methods with micro-volume HPLCs fitted with autoloaders and appropriately sized columns. It can also be given added value by being coupled to static-light scattering and refractive index detectors, allowing quantitative evaluation of excess detergent, micelle size and aggregation state [42]. SEC analysis can be streamlined further by eliminating other time-consuming purification steps, and using an in-line fluorescence detector to monitor the elution profiles of GFP-fusions directly from miniscule amounts of detergent-solubilized cell extracts [43]. Fluorescence can also be used to estimate expression levels of GFP-membrane protein fusions, as shown by Hannon et al. on of ~300 proteins from 18 bacterial and archeal extremophiles [44]. The authors find that after ‘benchmarking’ levels of fluorescence from the fusion tag to levels of target protein expression, they can easily detect membrane proteins produced in amounts suitable for structural studies. The only requirements are that the terminus of the protein that the GFP is attached to remains in the reducing environment of the cytoplasm, so that the GFP fluorescence develops properly [45]. This may render a percentage of membrane proteins not amenable to this technique. In addition, it may still be necessary to perform standard SDS-PAGE analysis to verify that the fluorescence signal recorded is from the intact, full-length fusion, rather than from truncation products.

The studies reviewed above and our own experience, allowed us to construct an expression and screening platform for prokaryotic membrane proteins, presented here.

Materials and Methods

Target selection protocol

In-depth discussion and experimental details for the target selection process can be found in [46]. The initial NYCOMPS target set comprised more than 300,000 annotated sequences from the RefSeq collection [47] belonging to 96 fully sequenced prokaryotic genomes. Since most targets have no experimental annotation linking them to the membrane, the prediction program TMHMM2 [48] was used to predict transmembrane helices (TMHs). Although prediction methods are estimated to be very accurate, they will inevitably make helix prediction mistakes. Therefore, we retained only proteins with ≥2 predicted TMHs. Following this step, redundancy was reduced by filtering out targets with exceedingly similar sequences, guaranteeing that no two proteins in our dataset shared more than 98% pairwise sequence identity (CD-hit; [49]). Furthermore, in order to minimize the probability of introducing water-soluble non-integral membrane proteins into our pipeline, sequences with 2 predicted TMHs, for which the position of the most N-terminal TMH overlapped with a predicted signal peptide sequence where excluded. Indeed, the most common mistake of TMH prediction programs is to predict an N-terminal TMH in place of a signal peptide [50]. Finally, target sequences were excluded in proteins that were predicted to have more than 15 consecutive disordered residues and hence might be problematic for crystallization [51]. The remaining 39,037 sequences constitute the “NYCOMPS98” dataset.

The targets to be cloned are selected from the NYCOMPS98 dataset of membrane proteins. Targets are selected following a two-step process. (1) Valid targets that either constitute promising candidates for structure determination and/or are of utmost biological interest are identified. These are referred to as “seeds”. (2) The seeds are expanded into families of typically homologous proteins that have a predicted membrane region structures similar to that of the seed. Only sequences that are part of the NYCOMPS98 set of valid targets were used for the expansion of the seeds. NYCOMPS seeds were chosen according to two distinct tracks that are referred to as “central selection” and “nomination”. Centrally selected seeds were selected from a list of proteins that have previously been successfully expressed in E. coli [45]. On the other hand, nominated seeds were “hand-picked” by laboratories participating in the NYCOMPS consortium and adjunct members from the community. Most of these seeds are well-characterized proteins of known function. One key difference between centrally selected and nominated seeds is that novelty is not enforced on the latter set. Instead, the observed similarities to proteins in the PDB was checked, and reported to the nominating group, which was ultimately responsible for the final decision on whether or not to pursue that specific target.

The seed expansion procedure is the same for centrally selected and nominated targets and is based on reciprocal sequence similarity in the predicted transmembrane (TM) region between the seed and the NYCOMPS98 set of target proteins. In particular, given a PSI-BLAST [52] alignment between the seed and a NYCOMPS98 protein with E-value <10−3, the requirement is that more than 50% of the residues predicted to be in TMHs in both proteins are aligned. After a seed is expanded into a family of proteins predicted to have similar TM cores, all family members are subject to additional filters. Firstly, any centrally selected target with significant similarity in the predicted TM region to proteins in the PDB (PSI-BLAST E-value <1 and alignment covering >25% of the target TM region) is filtered out. This filter is not applied to nominated targets. Secondly, all candidates for which there is evidence that they might constitute individual subunits of hetero-oligomeric complexes (using information extracted from EcoCyc; [53]) are removed from the list. Finally, there is a correction phase dedicated to “inconsistencies” within the families. Proteins for which the number of predicted TMHs differs greatly from that of the seed are typically discarded, as well as, proteins that differ significantly in their length with respect to the seed. Additionally, proteins that align well with the consensus N-terminus of the family (when any such consensus can be identified) but that have additional N-terminal amino acids, are typically excluded, because they often constitute cases of proteins that may have been erroneously annotated. In-depth discussion and experimental details for the target selection process can be found in [46].

Cloning procedures

Amplification primers are designed by “Primer prime’er”, a program for automated oligonucleotide construction developed by the North-Eastern Structural Genomics Consortium (NESG; [54]). Forward and reverse primers are supplied at a 5µM concentration in a pre-mixed form in 384 well blocks (IDT, Inc.).

In order to simplify our cloning process, we developed standard pNYCOMPS vectors for prokaryotic expression. These reagents and their sequence information are publicly available at the PSI Materials Repository (http://psimr.asu.edu/). Each plasmid carries a cassette harboring kanamycin resistance and is based on the IPTG inducible T7 promoter pET vector system (Novagen, Inc.). pNYCOMPS plasmids encodes a Tev protease [55] cleavable composite FLAG/deca-HIS affinity tag at either the N- or C-terminus. We have also introduced a ccdB “death gene” [56] within the plasmid to negatively select uncut or self-ligating vector thus abolishing background in the bacterial transformation following annealing.

96 genomic DNA templates were purchased from ATCC and arrayed in a single 96-well plate at working concentration (10ng/µL). A list of organisms from which the genomic DNAs were obtained can be found in [46]. A Biomek FX liquid handling robot (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) is used to assemble the amplification reaction in a 384-well plate by mixing a PCR master mix, primers and required matching template DNA in a final volume of 15µL. KOD Hot Start DNA Polymerase (Novagen, Inc.) is used in the amplification reaction with one standard set of cycling parameters. The high processivity and proofreading ability of this polymerase ensures a success rate of greater than 95% without need for further optimization. Standard conditions for PCR are as follows: 1x KOD Hot Start Buffer, 1.5mM MgSO4, 0.2mM (each) dNTPs, 0.3µM (each) primers, 30ng genomic template DNA, 10% DMSO, 0.02U/µL KOD Hot Start DNA Polymerase, and PCR Grade water to 15µL. PCR reactions are carried out in 384-well plates using standard cycling conditions: initial denatuation and activation, 2 minutes at 95°C, is followed by 40 cycles of denatuation for 15s at 95°C, annealing for 30s at 59°C, and elongation for 30s at 72°C.

After PCR amplification, samples are removed from the thermocycler, and they are assayed for the presence or absence of products of approximately the correct size by loading 2µL of each reaction onto a pre-cast, 96-well, ethidium bromide containing 2% agarose gel (E-Gel®; Invitrogen, Inc.). Inserts are purified using Agencourt Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization (SPRI) technology (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) in a 384-well format. SPRI uses selective capture of nucleic acids onto magnetic micro-particles, which can readily be washed prior to an elution step containing purified DNA [57]. Purified inserts are eluted in 15µL of Agencourt RE buffer.

Constructs are generated by ligation-independent cloning (LIC);[26]), a technique which is both simple to use and highly cost effective. T4 DNA Polymerase is used to generate complimentary single-stranded overhangs on both insert and linearized vector. Following treatment, insert and vector are mixed and incubated at 22°C for 1hr to allow spontaneous annealing of complimentary single-stranded overhangs.

In preparation for T4 DNA Polymerase treatment, cloning vectors pNYCOMPS-LIC-ccdB-TFH10+ (C-term.) and pNYCOMPS-LIC-ccdB-FH10T+ (N-term.) are digested with restriction enzymes BfuAI or SnaBI respectively. Following digestion, cut plasmids are run on preparative 1% agrose TBE gels and the linearized plasmid is excised from the gel and purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Inc.), eluted in low-EDTA TE buffer and diluted to a working concentration of 50ng/µL. LIC treatment reactions are generally performed in large batches, in 96-well thermocycler plates. Standard LIC treatment conditions for the vectors are as follows: 1x New England Biolabs, Inc. (NEB) Buffer 2, 1x NEB BSA, 25ng/µL vector, 2.5mM dGTP (N-term vector) or dCTP (C-term vector), 0.0375U/µL T4 DNA Polymerase, and PCR Grade water to final volume. Reactions are incubated at 22°C for 1hr followed by heat inactivation at 75°C for 20 minutes. Inserts are prepared in a manner similar to that of the cloning vectors. The only difference being that in order to make complimentary single-stranded overhangs, the purified PCR products are LIC treated in the presence of the complimentary nucleotide, dCTP for N-terminal inserts and dGTP for C-terminal inserts. The LIC insert master mix is as follows: 1x NEB Buffer 2, 1x NEB BSA, 2.5mM dCTP (N-terminal inserts) or dGTP (C-terminal inserts), 0.0375U/µL T4 DNA polymerase, and PCR Grade water to final volume. 8µL of the standard LIC insert master mix is combined with 2µL of purified PCR product and incubated at 22°C for 1 hr followed by heat inactivation at 75°C for 20 minutes.

After the vector and inserts have been LIC treated, 2µL of vector and 4µL of insert are combined and incubated at 22°C for 1hr. 2µL of 25mM EDTA pH 8.0 is added to each annealing reaction and incubated at 22°C for 5 minutes. Annealing reactions are typically performed in either 96- or 384-well plates according to scale of the experiment. Following this step, 1–2µL of circular plasmid is transformed into 20µL of phageresistant competent cells (DH10B–T1R-1), and plated on selective agar containing 25µg/mL kanamycin in 24-well blocks. Blocks are incubated overnight at 37°C. The following day, 1 colony per target is picked manually and grown in 800µL of 2xYT containing 25µg/mL kanamycin in a 96-well deep well block at 37°C in HT growth incubators (Vertiga; Thomson Instrument Company, Inc.) for 16hrs to amplify plasmid DNA. Agencourt CosMidPrep magnetic SPIR technology (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) is used to purify the DNA in an automated manner at a rate of six 96-well blocks every 3 hours. At this point, the identity and integrity of each construct is verified by sequencing by Agencourt Biosciences (Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

Small-scale expression screens

In order to test for expression and purification potential of each membrane protein target, expression plasmids are transformed into a phage resistant expression strain (BL21 (DE3) pLysS –T1R; Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.). 0.6mL cultures of each transformant are grown in 96-well deep-well block at 37°C in a HT growth incubator to an OD600nm of 0.6–1. Protein expression is induced by addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1mM, and growth is allowed to continue for an additional 4 hours. Upon harvest, final ODs600nm are typically in the range between 5 and 20.

Cell pellets are harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in a standard lysis buffer that does not contain detergent. A 96-well robotic sonicator probe was constructed for the ad hoc purpose of lysing cells in each individual well of a 96-well block. The block is maintained on a temperature-controlled platform during the entire sonication process.

Lysed cells are mixed with an n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM; Anatrace, Inc.) stock solution bringing the final concentration of detergent to 2%. After an incubation period of 1 hour at 4°C under gentle agitation, the lysate is robotically transferred to a 96-well filter plate, pre-loaded with metal affinity resin (Thomson Instrument Company, Inc. and GE lifesciences, Inc.). Lysates are incubated with the resin at 4°C for a minimum of 1 hour. Following this incubation step, lysates are removed by vacuum-assisted filtration, and the resin, which is retained in the filter plate, is washed twice with 1mL of wash buffer containing DDM at 0.02% and 50mM imidazole. The purified proteins are then eluted with a high concentration of imidazole (500mM). The proteins contained in the elution fraction are visualized by coomassie-blue R-250 staining of 26-well SDS-PAGE gels.

Medium-scale expression tests

Plasmids harboring genes coding for proteins expressing at suitable levels and purity as shown by the small-scale assay are re-arrayed in a 96-well format, transformed into expression strains, and these grown to high density in a GNFermenter (GNF Systems, Inc.). Cell pellets harvested from this fermenter are treated via the same processes as previously described for the small-scale expression screens, but the larger cell masses necessitate the use of 50mL tubes and 10mL drip columns, rather than 96-well blocks. These tubes and columns are conveniently arrayed in custom-made 96-well racks for processing. Purified proteins are eluted from the metal-affinity resin, and ~1/40th of the volume is run on an SDS-PAGE gel and proteins are detected, and yields estimated by staining with coomassie blue.

Detergent selection and stability assay

The eluted proteins from the previous step are each divided into 4, 40µl aliquots in a 96-well assay plate. The concentration of DDM in the elution buffer is 0.02% w/v. The chosen detergents, β-Octyl-Glucopyranoside (β-OG), n-Dodecyl-N,N-Dimethylamine-NOxide (LDAO), Tetraethylene glycol monooctyl ether (C8E4) and DDM, are added, as 4µl stock solutions, to 0.2% over the respective amount required to achieve a concentration of twice the CMC (i.e. the percentage for a 2xCMC solution for β-OG is 0.5%, hence this detergent is added to a final concentration of 0.7%) . This represents a excess of the second detergent and is meant to allow for at least partial replacement of the associated DDM molecules, carried from the metal-affinity chromatography elution step. After detergent addition and mixing, the plate is incubated at 25°C for two hours. Subsequently, the samples are centrifuged at 3000×g for 20 minutes to pellet any precipitate that has formed and the clear supernatant is transferred to the HPLC system. Samples are transferred to a thermostated holder, which is held at 4°C, in an Agilent 1200 HPLC equipped with a 4.6mm × 30cm TSK-Gel SuperSW3000 column (Tosoh Biosciences, Inc.). The column is equilibrated with gel filtration buffer containing 2xCMC DDM. Using the autosampler, 5µL of each sample is loaded onto the column and the elution from the column monitored at 280nm. The column has an approximate bed volume of 5 mL and a flow rate of 0.25mL/min is used. This process is repeated automatically until all of the samples have been processed.

Alternatively, the protein of choice can be assayed in a 12 detergent screen where iterative injections (5µL) of the eluted protein (in DDM buffer) are made onto a SEC column (4.6mm × 30cm TSK-Gel SuperSW3000 column) pre-equilibrated in the target detergent at 2xCMC. The detergents used are DDM, n-decyl-β-maltopyranoside (DM), n-Nonyl-β-maltopyranoside (NM), n-Octyl-β-maltopyranoside (OM), OG, n-Nonyl-β-glucopyranoside (NG), 5-Cyclohexyl-1-pentyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (Cymal-5), 4-Cyclohexyl-1-butyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (Cymal-4), Pentaethylene glycol monooctyl ether (C8E5), C8E4, Fos-choline 10 (FC-10) and FC-12. Elution profiles are optionally monitored by UV absorbance at 280nM, 3 angle static light scattering and refractive index detection using a miniDAWN™ TREOS system and Optilab® rEX (Wyatt Instruments, Inc.).

Results and Discussion

Target selection

Approximately 10,000 targets have been bio-informatically processed and selected from the “NYCOMPS98” dataset of ~39,000 integral membrane proteins, to date. Details can be found at the public databases TargetDB (http://targetdb.pdb.org/) and PepcDB (http://pepcdb.pdb.org/). The average number of membrane proteins we predicted in all 96 genomes is 24%, which is in line with other predictions. This number varies from 19% (Methanocaldococcus jannaschii) to 30% (Clostridium perfringens) [58, 59]. Most of the targets selected are between 100 and 500 amino acids in length and have between 2 and 12 predicted TMHs. 81% of all targets align to one or more Pfam-A families (HMMER E-value <10−3), with these families collectively covering more than half of the target predicted TM region. Full details of these experiments are published elsewhere (see [46]).

Automated Cloning

As of winter 2009, 6667 cloning attempts have been conducted resulting in 5113 sequence-verified constructs (77% success). Failures in cloning may result from any step in the process (PCR amplification, purification of inserts, LIC treatments, transformation or sequencing failure). Failure may also at times results from bioinformatics selection of inexistent targets due to incorrect annotation of sequences in public databases. Periodic re-processing of failed cloning efforts are made when sufficient numbers have built up, but these seem to recover only ~5% of targets at most.

Small and medium expression and purification trails

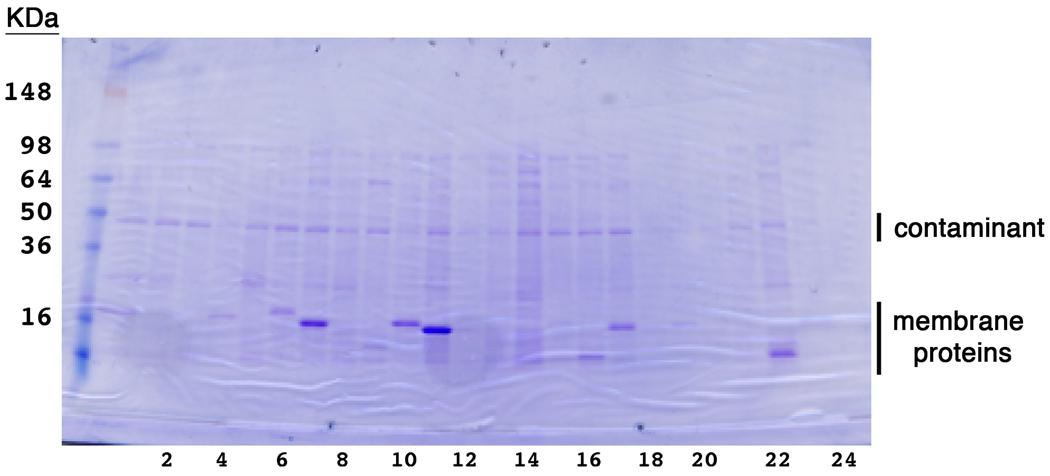

The goal of the NYCOMPS pipeline for expression and purification of membrane proteins is to identify samples that not only can be over-expressed, but that are also suitable for structural studies. Therefore, the small-scale expression tests have been designed and are conducted not only to monitor expression levels under a fixed and optimized set of parameters, but also to identify targets that can be purified to sufficient yields for the process to be cost-effective. The threshold for selection at this stage is that the yields of the membrane protein extracted from a 0.6mL culture in DDM and purified by metal-affinity chromatography be sufficient for detection on an SDS-PAGE stained with coomassie blue. Following this initial screening protocol, the lower expression limit is set to approximately 0.5 mg/L, a value deemed acceptable for cost-effective scale-up. DDM was selected as the ‘standard’ detergent due to its positive properties as determined by others [35] and by in-house conducted optimization experiments (data not show), and cost effectiveness. All these small-scale steps mirror the processes that are subsequently reused at a production scale for structural studies. An SDS-PAGE gel from a representative experiment conducted at this scale is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Representative results from small-scale expression tests. A 24-well SDS-PAGE gel stained with coomassie blue. Membrane proteins are purified from 0.6mL culture volumes. An omni-present contaminant is marked.

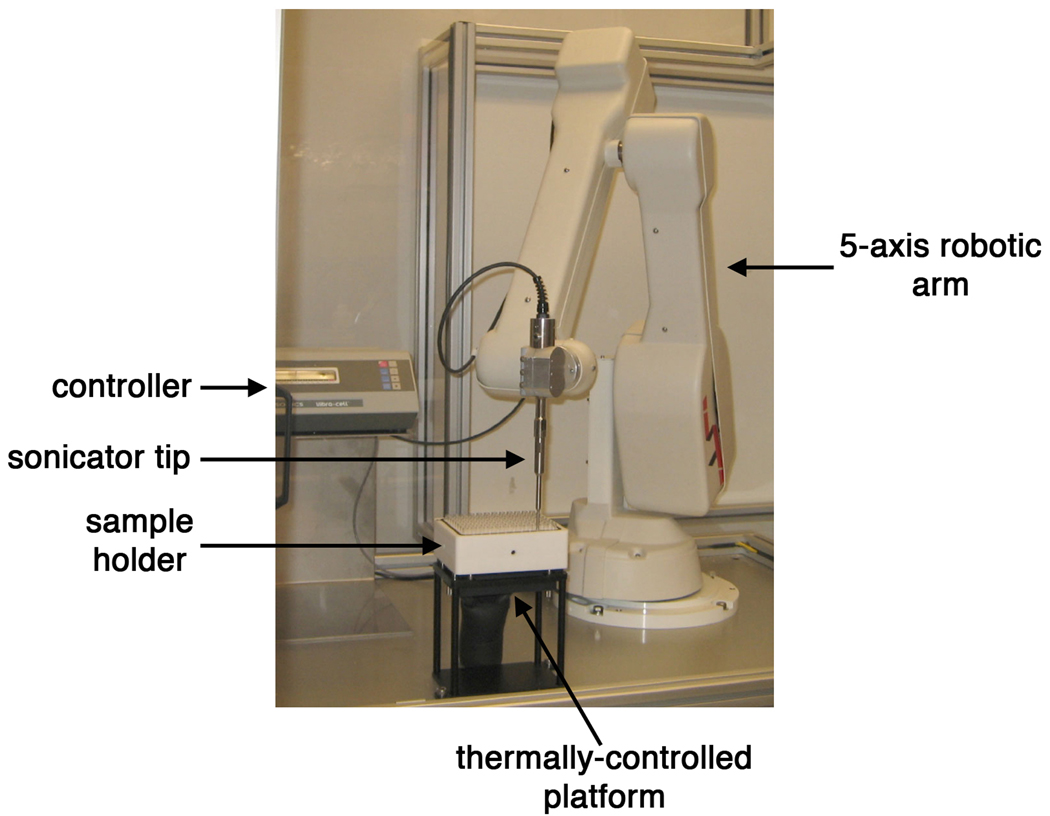

A prerequisite for these experiments was to identify a method for lysing a large number of membrane protein samples in parallel, without causing denaturation or aggregation. Chemical lysis solutions are not ideal for membrane proteins as they frequently contain unsuitably harsh detergents. Lysis by French-pressure cell cannot be adapted to 96, 0.6mL samples, and iterative rounds of freezing and thawing were deemed to be somewhat inefficient. Sonication was chosen as the most viable option. Plate sonicators or multi-head sonicators are commercially available, but the energy distribution has the tendency of being uneven, often leading to over-heating of some samples and no lysis of others. We therefore designed a robotic sonicator that consists of an electronically controlled sonicator probe mounted on a robot arm that can enter sequentially each well of a 96 well deepwell block, energize, and move to the next well in turn (Fig. 3). The sonicator head is kept energized momentarily after leaving the liquid surface but still within the confines of the block well to remove liquid attached to the probe. As a result, no cross-well contamination could be detected by western blot (data not shown). The block is held on a metal platform at 2°C to minimize heating and multiple, typically three at most, rounds of short bursts are used with a 13 minutes well-to-well delay time to minimize overheating. Processing of 96 samples is achieved in 13 to 39 minutes according to the number of rounds used. This robotic sonicator can also be used in conjunction with a robot-addressable 96 well ultra centrifuge to isolate membrane fractions in HT format, although this additional purification step was most often deemed unnecessary.

Figure 3.

Picture of custom-made sonicator robot. Key features are indicated with arrows. Sample holder, pictured here, can be interchanged with a 96-well deep-well block or with a custom-made holder for 6, 50mL centrifuge tubes.

Protein stability and aggregation state in different, “crystallization-friendly” detergents are assayed by SEC following an HT procedure. However, the amount of material necessary for these experiments requires a mid-scale growth culture. To this end, we have made use of an airlift fermenter (GNFermenter, GNF systems Inc.) that allows 96 independent cultures to be simultaneously grown to extremely high cell densities. The cell mass yield from ~70mLs of culture is typically equivalent to that obtained with ~500mL grown in a 2L shake flask. Moreover, expression yields for cells grown with the fermenter are comparable to those achieved in a 96-well deep well block, thus minimizing issues of scalability.

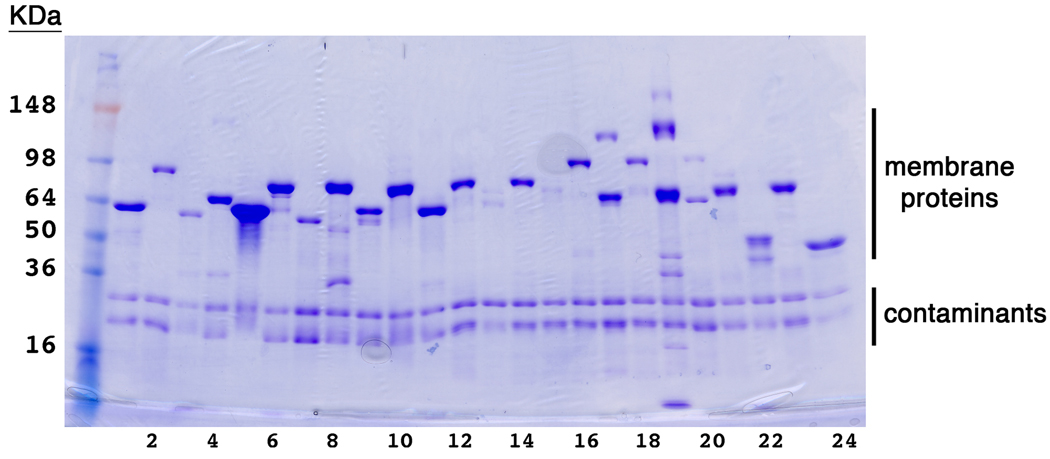

Typically, ~23% of membrane protein targets pass the small and mid-scale selection steps. This success rate is in agreement with that of other reports [33]. A representative gel of the material eluted from the metal-affinity chromatography step for the mid-scale expression and purification step is shown in Figure 4. These samples are then passed on to the stability screens discussed below.

Figure 4.

Representative results from mid-scale expression and purification tests Commassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of 24 purified membrane proteins form the medium-scale pipeline. 2.5% of the total volume eluted from the metal affinity chromatography step was loaded in each lane. Two contaminant bands are marked. Interestingly, these contaminants differ from those present in the small-scale expression screens. This difference could be due to different growth conditions of the bacteria.

Detergent selection and stability assays

The selection of purification detergent, and possibly more importantly the choice of crystallization detergent, is a critical decision in the entire process of membrane protein structure determination.

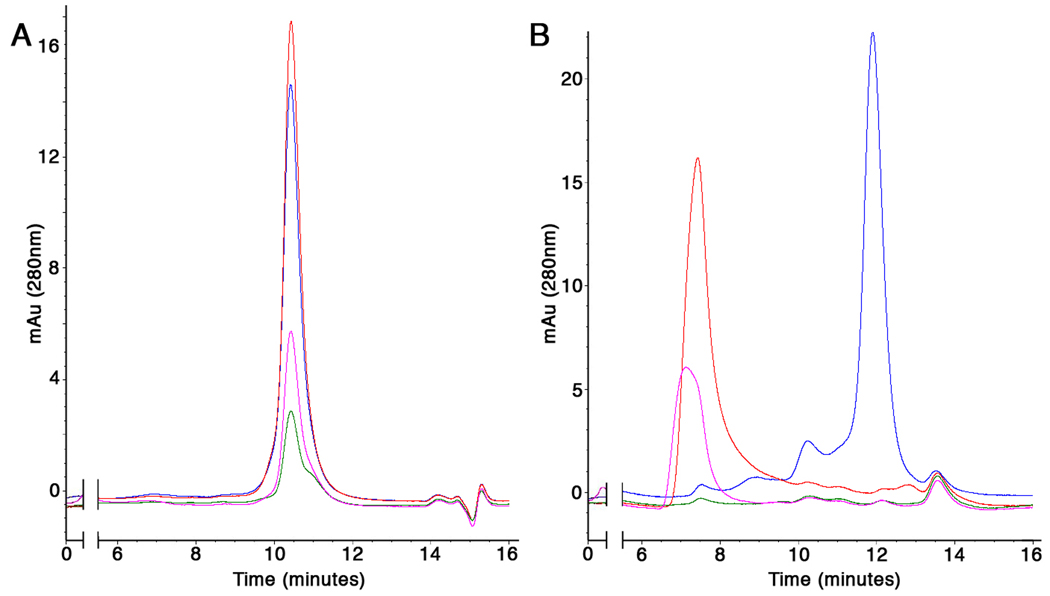

The capability of a given protein to withstand a ‘harsh’ detergent correlates with its stability, and stable proteins are more amenable to structural investigation. Therefore, we wished to select proteins that are stable at moderately elevated temperatures in large excesses of short chain detergents. Proteins yielding elution profiles from SEC that are unperturbed by this treatment are classified as stable, and are likely to perform well at production scale-up and/or crystallization. Proteins that are detergent-selective, are classified as workable. Proteins that do not behave well in any detergent are either discarded or redirected to a rescue pathway, depending on the importance of the target. Two examples derived from this assay are shown in Figure 5. In one case, the protein appears to withstand all conditions-albeit with a somewhat diminished yield in C8E4 and to a lesser extent, in β-OG (Fig. 5A). In contrast, a second protein appears to only tolerate DDM, as sample treated with other detergents elutes from SEC as an aggregate, in the void volume of the column (Fig. 5B). We typically perform this stability assay with three short-chain detergents (see legend to Figure 5), while we include only DDM in the mobile phase. This reduces running costs and time, thus increasing the throughput. Unfolding or aggregation of a membrane protein in a given short-chain detergent is typically an irreversible process, unlikely to be rescued by removal of the agent in a DDM-only containing mobile phase.

Figure 5.

Stability in short-chain detergents. SEC elution profiles of 2 different proteins treated with large excess of DDM (blue), C8E4 (green), LDAO (red) and β-OG (pink). The SEC experiments are performed with DDM included in the mobile phase at twice its CMC. Stability of the protein shown in (A) is apparent when compared to the one in (B), as indicated by presents of a large percentage of aggregated material which elutes after approximately 7 minutes, in the void volume of the column.

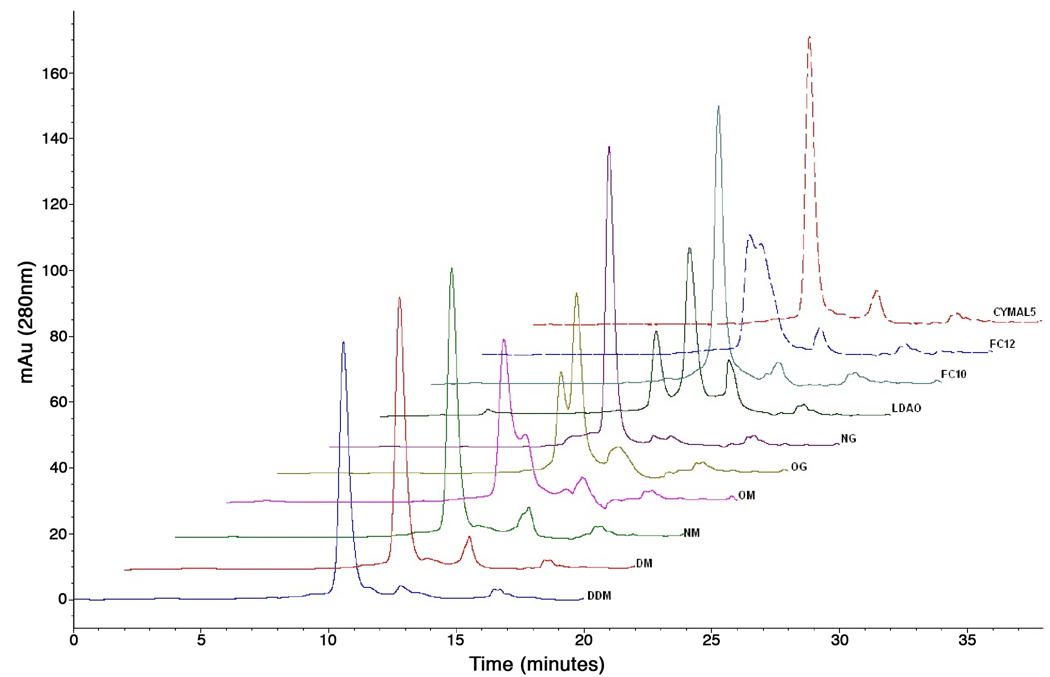

A second detergent assay consists of iteratively injecting the partially purified protein onto a SEC column pre-equilibriated in any one of 12 different detergent-containing mobile phases (see methods section for list of detergents). Arrayed UV traces for 1 protein are shown in Figure 6. Elution profiles are monitored by UV absorbance at 280nM, and optionally also by 3 angle static light scattering and refractive index detection. These data can be used to formulate an estimate of molecular weight, aggregation status and to determine the size of the protein/detergent micelle and build up a profile of detergent preference for a given protein. Adequate detergent exchange on the column often leads to a shift in the retention time of the elution peak and this be confirmed by calculations from the light scattering and refractive index detection [60, 61]. These data also allow detection and quantification of multimeric species.

Figure 6.

SEC-mediated detergent exchange. The elution traces are shown for one example protein run on a SEC column equilibrated with 12 different detergents in the mobile phase. The traces are shown in a staggered array, and the matching detergent is indicated above each. This protein yielded diffracting crystals.

Approximately 40% of samples that enter the gel filtration assays give a ‘positive’ elution profile in at least one detergent. These proteins are distributed for scale-up and crystallization experiments.

Conclusions

We present here a structural genomics pipeline for the HT targeting, cloning, expression, purification and biophysical characterization in different detergent of integral membrane proteins to select those most suitable for structural investigation. This pipeline has been used to target and process thousands of integral membrane proteins and produces many suitable targets for scale up. This highly-automated pre-selection approach serves to concentrate the resources for the labor-intensive downstream steps (crystallization and structure determination) on those proteins with highest probability of success.

Retrospective data analysis of proteins that successfully emerge from the screening processes provides precious feedback into our selection procedures for continuous rounds of improvement. Furthermore, the technologies and processes described herein, could, if deemed necessary, readily be modified to re-process targets under a different set of conditions.

The pipeline presented here has led to biologically-interesting structures such as a bacterial homologue of the kidney urea transporter [62] and a pentameric formate channel [63], with several others on the horizon.

Finally, it may be worth noting that the NYCOMPS facilities are available to the general community via the Protein Structure Initiative community-nominated targets proposal system (http://cnt.psi-structuralgenomics.org/CNT/targetlogin.jsp).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the NYCOMPS team of researchers who generated a substantial amount of the data presented in this manuscript. We are particularly grateful to Marco Punta (Columbia University and University of Munich) for the bioinformatics analysis, and to the following researchers at the NYCOMPS core laboratory at the New York Structural Biology Center, for the cloning, expression and purification of the targets: Brian Kloss, Patricia Rodriguez, Arianne Morrison, Renato Bruni and Brandan Hillerich. We also wish to acknowledge Larry Shapiro and Wayne Hendrickson for their invaluable contributions to the design and implementation of this platform. This work was funded by NIGMS GM075026 (Wayne Hendrickson, P.I.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wallin E, von Heijne G. Genome-wide analysis of integral membrane proteins from eubacterial, archaean, and eukaryotic organisms. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1029–1038. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berman H, Henrick K, Nakamura H. Announcing the worldwide Protein Data Bank. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:980. doi: 10.1038/nsb1203-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson R, Unwin PN. Three-dimensional model of purple membrane obtained by electron microscopy. Nature. 1975;257:28–32. doi: 10.1038/257028a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deisenhofer J, Epp O, Miki K, Huber R, Michel H. X-ray structure analysis of a membrane protein complex. Electron density map at 3 A resolution and a model of the chromophores of the photosynthetic reaction center from Rhodopseudomonas viridis. J Mol Biol. 1984;180:385–398. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(84)80011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grisshammer R, Tate CG. Overexpression of integral membrane proteins for structural studies. Q Rev Biophys. 1995;28:315–422. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mancia F, Hendrickson WA. Expression of recombinant G-protein coupled receptors for structural biology. MolBiosyst. 2007;3:723–734. doi: 10.1039/B713558K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mancia F, Patel SD, Rajala MW, Scherer PE, Nemes A, Schieren I, Hendrickson WA, Shapiro L. Optimization of protein production in mammalian cells with a coexpressed fluorescent marker. Structure (Camb) 2004;12:1355–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunji ER, Slotboom DJ, Poolman B. Lactococcus lactis as host for overproduction of functional membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1610:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendrickson WA. Determination of macromolecular structures from anomalous diffraction of synchrotron radiation. Science. 1991;254:51–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1925561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grisshammer R, Duckworth R, Henderson R. Expression of a rat neurotensin receptor in Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1993;295(Pt 2):571–576. doi: 10.1042/bj2950571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Midgett CR, Madden DR. Breaking the bottleneck: eukaryotic membrane protein expression for high-resolution structural studies. J Struct Biol. 2007;160:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzales EB, Kawate T, Gouaux E. Pore architecture and ion sites in acid-sensing ion channels and P2X receptors. Nature. 2009;460:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature08218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanson MA, Stevens RC. Discovery of new GPCR biology: one receptor structure at a time. Structure. 2009;17:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawate T, Michel JC, Birdsong WT, Gouaux E. Crystal structure of the ATP-gated P2X(4) ion channel in the closed state. Nature. 2009;460:592–598. doi: 10.1038/nature08198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long SB, Campbell EB, Mackinnon R. Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel. Science. 2005;309:897–903. doi: 10.1126/science.1116269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobolevsky AI, Rosconi MP, Gouaux E. X-ray structure, symmetry and mechanism of an AMPA-subtype glutamate receptor. Nature. 2009;462:745–756. doi: 10.1038/nature08624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tao X, Avalos JL, Chen J, MacKinnon R. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic strong inward-rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2 at 3.1 A resolution. Science. 2009;326:1668–1674. doi: 10.1126/science.1180310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiener MC. A pedestrian guide to membrane protein crystallization. Methods. 2004;34:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemieux MJ, Song J, Kim MJ, Huang Y, Villa A, Auer M, Li XD, Wang DN. Three-dimensional crystallization of the Escherichia coli glycerol-3-phosphate transporter: a member of the major facilitator superfamily. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2748–2756. doi: 10.1110/ps.03276603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serrano-Vega MJ, Magnani F, Shibata Y, Tate CG. Conformational thermostabilization of the beta1-adrenergic receptor in a detergent-resistant form. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:877–882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711253105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warne T, Serrano-Vega MJ, Tate CG, Schertler GF. Development and crystallization of a minimal thermostabilised G protein-coupled receptor. Protein Expr Purif. 2009;65:204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dessailly BH, Nair R, Jaroszewski L, Fajardo JE, Kouranov A, Lee D, Fiser A, Godzik A, Rost B, Orengo C. PSI-2: structural genomics to cover protein domain family space. Structure. 2009;17:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joachimiak A. High-throughput crystallography for structural genomics. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:573–584. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terwilliger TC, Stuart D, Yokoyama S. Lessons from structural genomics. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:371–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graslund S, Nordlund P, Weigelt J, Hallberg BM, Bray J, Gileadi O, Knapp S, Oppermann U, Arrowsmith C, Hui R, Ming J, dhe-Paganon S, Park HW, Savchenko A, Yee A, Edwards A, Vincentelli R, Cambillau C, Kim R, Kim SH, Rao Z, Shi Y, Terwilliger TC, Kim CY, Hung LW, Waldo GS, Peleg Y, Albeck S, Unger T, Dym O, Prilusky J, Sussman JL, Stevens RC, Lesley SA, Wilson IA, Joachimiak A, Collart F, Dementieva I, Donnelly MI, Eschenfeldt WH, Kim Y, Stols L, Wu R, Zhou M, Burley SK, Emtage JS, Sauder JM, Thompson D, Bain K, Luz J, Gheyi T, Zhang F, Atwell S, Almo SC, Bonanno JB, Fiser A, Swaminathan S, Studier FW, Chance MR, Sali A, Acton TB, Xiao R, Zhao L, Ma LC, Hunt JF, Tong L, Cunningham K, Inouye M, Anderson S, Janjua H, Shastry R, Ho CK, Wang D, Wang H, Jiang M, Montelione GT, Stuart DI, Owens RJ, Daenke S, Schutz A, Heinemann U, Yokoyama S, Bussow K, Gunsalus KC. Protein production and purification. Nat Methods. 2008;5:135–146. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aslanidis C, de Jong PJ. Ligation-independent cloning of PCR products (LIC-PCR) Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6069–6074. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark KM, Fedoriw N, Robinson K, Connelly SM, Randles J, Malkowski MG, Detitta GT, Dumont ME. Purification of transmembrane proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae for X-ray crystallography. Protein Expr Purif. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liguori L, Marques B, Villegas-Mendez A, Rothe R, Lenormand JL. Production of membrane proteins using cell-free expression systems. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2007;4:79–90. doi: 10.1586/14789450.4.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwarz D, Dotsch V, Bernhard F. Production of membrane proteins using cell-free expression systems. Proteomics. 2008;8:3933–3946. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page R, Moy K, Sims EC, Velasquez J, McManus B, Grittini C, Clayton TL, Stevens RC. Scalable high-throughput micro-expression device for recombinant proteins. Biotechniques. 2004;37:364–366. doi: 10.2144/04373BM05. 368 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lesley SA, Kuhn P, Godzik A, Deacon AM, Mathews I, Kreusch A, Spraggon G, Klock HE, McMullan D, Shin T, Vincent J, Robb A, Brinen LS, Miller MD, McPhillips TM, Miller MA, Scheibe D, Canaves JM, Guda C, Jaroszewski L, Selby TL, Elsliger MA, Wooley J, Taylor SS, Hodgson KO, Wilson IA, Schultz PG, Stevens RC. Structural genomics of the Thermotoga maritima proteome implemented in a high-throughput structure determination pipeline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11664–11669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142413399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brodsky O, Cronin CN. Economical parallel protein expression screening and scale-up in Escherichia coli. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2006;7:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s10969-006-9013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobrovetsky E, Lu ML, Andorn-Broza R, Khutoreskaya G, Bray JE, Savchenko A, Arrowsmith CH, Edwards AM, Koth CM. High-throughput production of prokaryotic membrane proteins. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2005;6:33–50. doi: 10.1007/s10969-005-1363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dobrovetsky E, Menendez J, Edwards AM, Koth CM. A robust purification strategy to accelerate membrane proteomics. Methods. 2007;41:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewinson O, Lee AT, Rees DC. The funnel approach to the precrystallization production of membrane proteins. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yatime L, Buch-Pedersen MJ, Musgaard M, Morth JP, Lund Winther AM, Pedersen BP, Olesen C, Andersen JP, Vilsen B, Schiott B, Palmgren MG, Moller JV, Nissen P, Fedosova N. P-type ATPases as drug targets: tools for medicine and science. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eshaghi S, Hedren M, Nasser MI, Hammarberg T, Thornell A, Nordlund P. An efficient strategy for high-throughput expression screening of recombinant integral membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 2005;14:676–683. doi: 10.1110/ps.041127005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartley JL, Temple GF, Brasch MA. DNA cloning using in vitro sitespecific recombination. Genome Res. 2000;10:1788–1795. doi: 10.1101/gr.143000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klock HE, Koesema EJ, Knuth MW, Lesley SA. Combining the polymerase incomplete primer extension method for cloning and mutagenesis with microscreening to accelerate structural genomics efforts. Proteins. 2008;71:982–994. doi: 10.1002/prot.21786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willis MS, Koth CM. Structural proteomics of membrane proteins: a survey of published techniques and design of a rational high throughput strategy. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;426:277–295. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang DN, Safferling M, Lemieux MJ, Griffith H, Chen Y, Li XD. Practical aspects of overexpressing bacterial secondary membrane transporters for structural studies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1610:23–36. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veesler D, Blangy S, Siponen M, Vincentelli R, Cambillau C, Sciara G. Production and biophysical characterization of the CorA transporter from Methanosarcina mazei. Anal Biochem. 2009;388:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawate T, Gouaux E. Fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography for precrystallization screening of integral membrane proteins. Structure. (2006);14:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammon J, Palanivelu DV, Chen J, Patel C, Minor DL., Jr A green fluorescent protein screen for identification of well-expressed membrane proteins from a cohort of extremophilic organisms. Protein Sci. 2009;18:121–133. doi: 10.1002/pro.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daley DO, Rapp M, Granseth E, Melen K, Drew D, von Heijne G. Global topology analysis of the Escherichia coli inner membrane proteome. Science. 2005;308:1321–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.1109730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Punta M, Love J, Handelman S, Hunt JF, Shapiro L, Hendrickson WA, Rost B. Structural genomics target selection for the New York consortium on membrane protein structure. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2009;10:255–268. doi: 10.1007/s10969-009-9071-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:61–65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moller S, Croning MD, Apweiler R. Evaluation of methods for the prediction of membrane spanning regions. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:646–653. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.7.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Esnouf RM, Hamer R, Sussman JL, Silman I, Trudgian D, Yang ZR, Prilusky J. Honing the in silico toolkit for detecting protein disorder. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1260–1266. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906033580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keseler IM, Bonavides-Martinez C, Collado-Vides J, Gama-Castro S, Gunsalus RP, Johnson DA, Krummenacker M, Nolan LM, Paley S, Paulsen IT, Peralta-Gil M, Santos-Zavaleta A, Shearer AG, Karp PD. EcoCyc: a comprehensive view of Escherichia coli biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D464–D470. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Everett JK, Acton TB, Montelione GT. Primer Prim'er: a web based server for automated primer design. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2004;5:13–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029238.86387.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kapust RB, Tozser J, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. The P1' specificity of tobacco etch virus protease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:949–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernard P, Couturier M. Cell killing by the F plasmid CcdB protein involves poisoning of DNA-topoisomerase II complexes. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:735–745. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90629-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DeAngelis MM, Wang DG, Hawkins TL. Solid-phase reversible immobilization for the isolation of PCR products. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4742–4743. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.22.4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knight CG, Kassen R, Hebestreit H, Rainey PB. Global analysis of predicted proteomes: functional adaptation of physical properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8390–8395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307270101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu J, Rost B. Comparing function and structure between entire proteomes. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1970–1979. doi: 10.1110/ps.10101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hayashi Y, Matsui H, Takagi T. Membrane protein molecular weight determined by low-angle laser light-scattering photometry coupled with highperformance gel chromatography. Methods Enzymol. 1989;172:514–528. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(89)72031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Slotboom DJ, Duurkens RH, Olieman K, Erkens GB. Static light scattering to characterize membrane proteins in detergent solution. Methods. 2008;46:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levin EJ, Quick M, Zhou M. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of the kidney urea transporter. Nature. 2009;462:757–761. doi: 10.1038/nature08558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Waight AB, Love J, Wang DN. Structure and mechanism of a pentameric formate channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]