Abstract

Trisomy 10 as the sole cytogenetic abnormality in AML is rare, with an incidence rate of < 0.5%. It tends to affect the elderly and is extremely rare in pediatric patients. We describe a case of an 8-month-old Caucasian baby who presented with prominence of left eye and fever without lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Bone survey showed diffuse periosteal reaction in the femur, pelvis, maxillary and orbital bones (with fracture). CBC revealed normal white blood cell count with increased blasts, mild anemia and moderate thrombocytopenia. Bone marrow biopsy showed increased myeloblasts with bilineage dysplasia and 3-4+ reticulin fibrosis. Flow cytometry revealed blasts positive for CD34, CD33, and MPO and negative for CD7, CD13, and HLA-DR. Trisomy 10 was demonstrated by chromosome analysis and fluorescence in-situ hybridization. The patient received induction chemotherapy and achieved complete clinical and hematologic remission at day 28. However, he relapsed after three cycles of chemotherapy. Compared to the two other reported pediatric cases, our patient has some unique features such as much younger age and additional findings such as bilineage dysplasia and bone marrow fibrosis. Both reported cases and our case were classified as AML-M2 indicating that this may be a common subtype in pediatric patients. Bone involvement was present in our patient and one other case and both had similar immunophenotype (CD33+, CD7-). These findings suggest that isolated trisomy 10 may be associated with distinct clinicopathologic features in pediatric AML. Studies on additional patients are needed to establish this association.

Keywords: Trisomy 10, acute myeloid leukemia, infant, review, CD7, CD13, CD33, CD34

Introduction

Trisomy 10 as a sole cytogenetic abnormality has been uncommonly described in a variety of hematopoietic malignancies including acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and myelodys-plastic syndrome (MDS). However, it is extremely rare in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) particularly in the pediatric age group. The incidence ranges from 0.2% to 0.5% of AML, with only 22 cases having been reported thus far [1-4]. This cytogenetic abnormality has been reported in association with most French American British (FAB) subtypes except FAB-M3. Majority of reported cases were adults, ranging from 29 to 80 years of age with intermediate to poor prognosis. The two reported pediatric cases were a 2-year-old Japanese boy and a 7-year-old boy [5,6]. Here we report the third pediatric AML case with trisomy 10, including clinical and histological features in comparison to those reported in the literature.

Case report

An 8-month-old Caucasian boy presented with a prominence of the left eye, episodes of fever, and a delay in motor development. On physical examination, there were no skin rashes, lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. X-ray, bone survey and CT scan showed diffuse periosteal reaction in the femur, pelvis, maxillary and orbital bones (with fracture). Biochemical studies showed markedly elevated levels of C-reactive protein 15,900 mg/dL (normal 0-0.74 mg/dL), and lactate dehydrogenase 1,015 u/L (normal 120-246 u/L).

The initial CBC (Table 1) did not show increased blasts or thrombocytopenia. A week later, CBC revealed a normal white blood cell count of 11.7 k/mm3 with 8% blasts (Table 1). Moderate normocytic anemia and thrombocytopenia were present. Tear drop red blood cells, hypogranular and hyposegmented neutrophils were present in the peripheral blood smear.

Table 1.

Complete Blood Count (CBC) count and WBC differential

| CBC | First CBC | Second CBC | Reference range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hgb (g/dl) | 8.8 | 9.6 | |

| MCV (fl) | 80.8 | 84.1 | |

| Platelet (k/mm3) | 216 | 87 | 150–450 |

| WBC (k/mm3) | 12.0 | 11.7 | 6–14 |

| Blasts (%) | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Myelocytes (%) | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Bands (%) | 2 | 7 | |

| Neutrophils (%) | 69 | 24 | |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 22 | 46 | |

| Monocytes (%) | 4 | 9 | |

| Eosinophils (%) | 3 | 4 | |

| Basophils (%) | 0 | 0 |

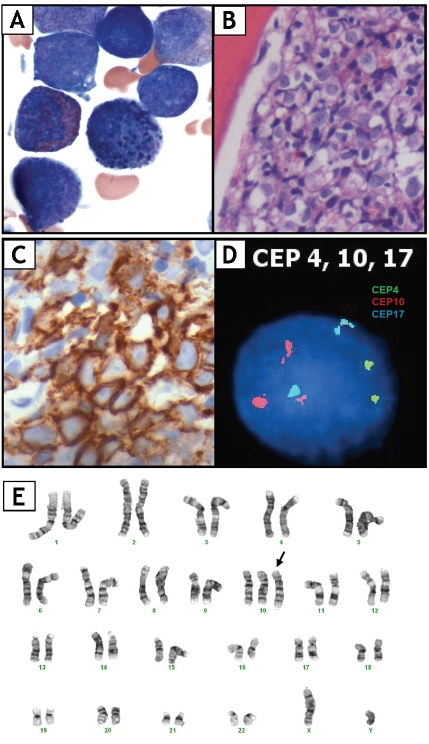

The patient underwent biopsies of bone marrow (BM) biopsy and the left femoral lesion. BM biopsy was 100% cellular with increased myeloblasts (25%) and mild eosinophilia (Figure IB). Blasts were type II myeloblasts characterized by presence of increased N/C ratio, fine cytoplasmic granules and open chromatin. No Auer rods were seen. Mild dyserythropoiesis characterized by nuclear hyperlobation and multinucleation. Dysplastic eosinophilic precursors containing coarse basophilic granules were also noted (Figure 1A). In addition, 3-4+ reticulin fibrosis was observed. Flow cytometry analysis of BM demonstrated a population of blasts (25%) expressing CD33, CD34, weak CD117, and MPO, but was negative for HLA-DR, CD7, CD13, and TdT. CD34 (Figure 1C), CD117 and MPO positivity were further confirmed by immunohistochemistry. BM aspirate and biopsy findings were consistent with AML-M2. The patient received induction chemotherapy consisting of cytosine arabinoside (intravenous and intrathecal), etoposide and daunorubicin and achieved complete clinical and hematologic remission at day 28. However, he relapsed in 3 months after three cycles of chemotherapy.

Figure 1.

(A) Bone marrow aspirate showing type II myeloblasts and a dysplastic eosinophilic precursor with coarse basophilic granules. (B) Bone marrow biopsy revealing sheets of blasts. (C) Blasts demonstrating CD34 positivity by IHC. (D) FISH using CEP10 on cultured bone marrow cells showing three copies of chromosome 10 (red signal). (E) Karyotype of bone marrow cells showing trisomy of chromosome 10.

Cytogenetic and fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis

Chromosome analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) were preformed at diagno sis on cultured bone marrow cells. Twenty meta- phases were analyzed by the conventional tryp- sin-Giemsa (G-) banding technique and three showed 47,XY,+10 (Figure IE), which was fur ther confirmed by centromeric enumeration probe (CEP) for chromosome 10 by FISH (Figure ID). No other clonal abnormalities were identi fied by FISH using probes specific for rearrange ment at MLL locus, PML-RARA fusion or recur rent abnormalities in MDS (ETO/AML1 fusion, monosomy5/deletion5q, monosomy7/ deletion7q, deletionl3q, inv(16), del(20q), CBFB, 20ql2).

At the time of relapse, trisomy 10 was identified in 4 of 800 cells by FISH. However, cytogenetic analysis of cultured bone marrow cells did not demonstrate any clonal chromosome abnormality in any of the 20 metaphase cells analyzed.

Discussion

AML with trisomy 10 as the sole cytogenetic abnormality is rare with an incidence rate of < 0.5%. Though AML with trisomy 10 can occur at all ages it tends to affect adults with mean age of 54. The male to female ratio is about 2:1. Half of the cases have been seen in patients of Asian descent, including one reported pediatric case. The clinical presentation is variable. Review of published cases of trisomy 10 (Table 2) showed the most common FAB subtypes were MO, Ml, and M2. In adults, 7 of 11 (78%) CD7 positive cases also co-expressed CD33, which is likely a common immunophenotype in this group of patients. Survival data were available in 18 cases (Table 2) with median follow-up time of 11 months. The prognosis seems to be intermediate to poor in these patients, with the median survival of 33 months.

Table 2.

Clinico-hematological and cytogenetic findings of trisomy 10 in AML

| Case | Race | Age/sex | Presentation | Dx | WBC(109/L) | Blasta(%) | Positive Surface marker | Trisomy 10b | Survival (month) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric cases | ||||||||||

| 1 | Japanese | 2/M | Fever, petechiae, LA, HSM, bone lesions | M2 | 61.6 | 91.6 | CD13/15/33 | NA | 14 | [6] |

| 2 | NA | 7/M | Fever, photophobia, headache, double vision | M2 | 3.7 | 52 | CD7/13/15/33/34/38/56 | NA | 12+ | [5] |

| 3 | Caucasian | 8 mos | Fever, bone lesions | M2 | 11.7 | 25% | CD33/34/117/MPO | 3/20 | 3+ | current case |

| Adult cases | ||||||||||

| 4 | Japanese | 66/M | Hepatomegaly, LA | M0 | 7.8 | 31 | CD7/33/HLA-DR | NA | 2 | [4] |

| 5 | NA | 78/F | Dehydration, fatigue, LA, HSM | M0 | 51.3 | 38 (PB) | CD5/7/13/33/34 | 11/19 | NA | [11] |

| 6 | Japanese | 80/F | Anemia, LA | M0 | 4.9 | 94 | CD7/33 | 8/8 | 4 | [1] |

| 7 | Chinese | 29/M | Gum bleeding | M1 | 3.5 | 88 | NA | 3/13 | 60+ | [12] |

| 8 | Japanese | 43/M | NA | M1 | 11.0 | 77 | CD7/10/13/HLA-DR | NA | 54+ | [4] |

| 9 | Japanese | 48/M | NA | M1 | 7.1 | 86 | CD13/33/HLA-DR | NA | 38 | [4] |

| 10 | Chinese | 51/F | NA | M1 | 260 | 87 | CD7, HLA-DR | NA | 14+ | [13] |

| 11 | Chinese | 37/F | NA | M2 | 21.8 | 9 | CD7/13/33,HLA-DR | NA | NA | [13] |

| 12 | Caucasian | 45/M | Anemia | M2 | NA | NA | CD7/13/33/34/HLA-DR | 17/20 | 10+ | [14] |

| 13 | Japanese | 57/M | Weight loss, loss of appetite, cough | M2 | 4.5 | 64 | CD7/13/33/34/38/HLA-DR | 3/19 | 16+ | [1] |

| 14 | Spanish | 65/M | Asymptomatic | M2 | 6.1 | 50 | CD7/13/33/34/HLA-DR | 33/35 | 33 | [3] |

| 15 | Italian | 72/M | NA | M2 | NA | 47 | CD13/33/34/45/HLA-DR | NA | NA | [2] |

| 16 | Italian | 75/M | NA | M2 | NA | NA | CD33 | NA | NA | [15] |

| 17 | NA | 69/F | Fever | M4 | 5.2 | 50 | NA | 10/24 | 34 | [16] |

| 18 | NA | 63/M | Exposed to organic solvents | M5 | NA | NA | NA | 12/12 | NA | [17] |

| 19 | Chinese | 60/F | NA | M6 | 3.8 | 32 | NG | 2/10 | 6 | [8] |

| 20 | NA | 68/F | Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, bruising, fatigue | M6, dysplasia, fribrosis | 9.7 | 85 | CD7/11c/13/33/Glycophorin A | 15/15 | 1 | [7] |

| 21 | NA | 72/M | LA | M7 | 9.3 | 85 | NA | 32/32 | 8 | [16] |

| 22 | Caucasian | 43/M | Joint pain, lethargy, SOB, weight loss | NA, fibrosis | NA | NA | CD13/15/33 | 13/18 | 5 | [14] |

| 23 | Chinese | 59/M | NA | NA | 68 | 36(PB) | NA | 2/4 | 122 | [8] |

percentage of blasts in BM;

proportion of trisomy 10 in karyotyped metaphases; Dx: diagnosis; HSM: hepatosplenomegaly; LA: lymphoadenopathy; NA: not available; PB: peripheral blood; SOB: shortness of breath

The two reported pediatric cases and our patient share several common features. All three were males (case #1, 2 & 3, Table 2) and morphologically were all consistent with FAB AML-M2. The clinical presentation of all three cases was atypical in that one presented with meningitis and other two presented with bone lesions [5,6]. Our case and patient #1 (Table 2) shared many similar findings include presentation with bone lesions. Both cases had type II myeloblasts with fine granules in the cytoplasm, but no characteristic morphological features have been described in patients with trisomy 10 in the literature. In both patients the blasts were negative for CD7 but positive for CD33.

On the other hand, our case also had some unique features. The patient was much younger (8-months vs. 7- and 2-years) and there was morphologic evidence of myelodysplasia. The presence of bilineage dysplasia and BM fibrosis suggests that this AML may have arisen from underlying MDS, though FISH was negative for recurrent clonal abnormalities in MDS. Only one other case (#20) revealed both trilineage dysplasia and fibrosis of in an adult patient with AML M6, who died 26 days after admission [7]. Two adults cases of MDS with trisomy 10, have been reported, but survival data was not available for these cases [8,9]. One pediatric patient (case #2) had allogeneic stem cell transplantation after high-dose intravenous and intrathecal chemotherapy. He was alive a year after diagnosis at the time of report [5]. The other pediatric patient with bone lesions (case #1) exhibited an unfavorable prognosis: the patient relapsed in 6 months and expired 14 months after initial diagnosis [6]. Though our patient initially responded well to induction chemotherapy, he relapsed in 3 months and had several adverse prognostic indicators including associated dysplasia, fibrosis and extremely young age.

The impact of trisomy 10 on prognosis in the reported cases is variable. Pedersen et al observed that in AML and ALL patients, trisomy 10 clonal size directly correlated with peripheral blood leukocyte count in that small clones tended to be associated with few to no circulating blasts and vice versa. [8]. The authors hypothesized that trisomy 10 cells are highly malignant and that clinical progression from pre-malignantto malignant conditions is associated with clonal expansion. However, there was no difference in survival in patients with small clones versus those with large clones, which did not lend support to their initial hypothesis. Review of all AML with trisomy 10 cases, clone size data, WBC, and percentage of blasts were available in 11 cases (Table 2). Analysis of these cases revealed no correlation between the clone size with WBC or with percentages of blasts (r=0.257, p=0.435, and r=0.576, p=0.066, respectively, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient method). Interestingly, Sakai et al found the trisomy 10 disappeared at relapse in a pediatric patient [6], whereas another report showed addition of trisomy 10 at relapse [10]. In light of these variable reports and few cases in the literature, the role of trisomy 10 in disease progression and overall prognosis remains unclear.

In summary, trisomy 10 is a rare isolated numerical chromosomal abnormality in AML. The clinical and hematological features in adults are broad and variable. It is interesting that the two pediatric patients who presented with bone lesions had similar histology and immunophenotype (CD7-/CD33+). Review of additional cases is necessary to determine if trisomy 10 is in fact associated with unique immunomorphological features and an adverse prognostic indicator in the pediatric age group.

References

- 1.Ohyashiki K, Kodama A, Nakamura H, Wakasugi K, Uchida H, Shirota T, Ito H, Toyama K. Trisomy 10 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1996;89:114–117. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(95)00263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estalilla 0, Rintels P, Mark HF. Trisomy 10 in leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1998;101:68–71. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(97)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luno E, Payer AR, Luengo JR, Del Castillo TB, Garcia VP. Trisomy 10 in acute myeloid leukemia: report of a new case. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1998;100:84–87. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(97)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki A, Kimura Y, Ohyashiki K, Kitano K, Kageyama S, Kasai M, Miyawaki S, Ohno R. Trisomy 10 in acute myeloid leukemia. Three additional cases from the database of the Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group (JALSG) AML-92 and AML-95. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;120:141–143. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Orazio JA, Burns LA, Farhoudi N, McBride MT, Kesler MV. Acute myelogenous leukemia presenting as acute infectious meningitis in a 7-year-old boy. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009;48:444–448. doi: 10.1177/0009922808330779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakai Y, Nakayama H, Matsuzaki A, Nagatoshi Y, Suminoe A, Honda K, Inamitsu T, Ohga S, Hara T. Trisomy 10 in a child with acute nonlym-phocytic leukemia followed by relapse with a different clone. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;115:47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czepulkowski B, Powell AR, Pagliuca A, Mufti GJ. Trisomy 10 and acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2002;134:81–83. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00593-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen B, Andersen CL, Sogaard MM, Norgaard JM, Koch J, Krejci K, Brandsborg M, Clausen N. Trisomy 10 survival: a literature review and presentation of seven new cases. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1998;103:130–132. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(97)00387-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Der Lely N, Poddighe P, Wessels J, Hopman A, Geurts van Kessel A, De Witte T. Clonal analysis of progenitor cells by interphase cytogenetics in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia. Leukemia. 1995;9:1167–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotoh M, Sasaki Y, Iguchi T, Fujimoto H, Kodama A, Kiyoi H, Naoe T, Ohyashiki K. Karyotypically independent clones with del(11q) and trisomy 10 in acute myeloid leukemia: trisomy 10 may appear as an additional change. Int J Hematol. 2008;88:123–124. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan R, Chen Z, Stone JF, Cohen J, Gustafson E, Jolly PC, Sandberg AA. Trisomy 10: age and leukemic lineage associations. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1996;89:173–174. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(96)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma SK, Wan TS, Chan LC, Au WY. Trisomy 10 in acute myeloid leukemia: revisited. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;109:88–89. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(98)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tien HF, Wang CH, Su IJ, Liu FS, Wu HS, Chen YC, Lin KH, Lee SC, Shen MC. A subset of acute nonlymphocytic leukemia with expression of surface antigen CD7-morphologic, cytochemical, immunocytochemical and T cell receptor gene analysis on 13 patients. Leuk Res. 1990;14:515–523. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(90)90003-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llewellyn IE, Morris CM, Stanworth S, Heaton DC, Spearing RL. Trisomy 10 in acute myeloid leukemia: three new cases. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;118:148–150. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estalilla O, Rintels P, Mark HF. Trisomy 10 as a sole chromosomal abnormality in AML-M2. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;108:175. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(98)00078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berger R, Busson-Le Coniat M. Are cells with trisomy 10 always malignant in hematopoietic disorders? Ann Genet. 1999;42:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuneo A, Fagioli F, Pazzi I, Tallarico A, Previati R, Piva N, Carli MG, Balboni M, Castoldi G. Morphologic, immunologic and cytogenetic studies in acute myeloid leukemia following occupational exposure to pesticides and organic solvents. Leuk Res. 1992;16:789–796. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(92)90158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]