Abstract

Objective

This study examines the relationship of neighborhood climate (i.e., neighborhood social environment) to perceived social support and mental health outcomes in older Hispanic immigrants.

Method

A population-based sample of 273 community-dwelling older Hispanic immigrants (aged 70 to 100) in Miami, Florida, completed self-report measures of neighborhood climate, social support, and psychological distress and performance-based measures of cognitive functioning. Structural equation modeling was used to model the relationship of neighborhood climate to elders' perceived social support and mental health outcomes (i.e., cognitive functioning, psychological distress).

Results

Neighborhood climate had a significant direct relationship to cognitive functioning, after controlling for demographics. By contrast, neighborhood climate had a significant indirect relationship to psychological distress, through its relationship to perceived social support. Moreover, social support mediated the relationship between neighborhood climate and psychological distress.

Discussion

Findings suggest that a more positive neighborhood social environment may be associated with better mental health outcomes in urban, older Hispanic immigrants.

Keywords: neighborhood climate, social environment, mental health, psychological distress, cognitive functioning, social support, Hispanics, Latinos, older adults, immigrants

Although much work has shown that supportive interactions with friends and family can have beneficial effects for older adults' health and mental health (e.g., Bisconti & Bergeman, 1999; Zunzunegui, Alvarado, Del Ser, & Otero, 2003), relatively few studies have examined the potentially salutary effects of older adults' interactions with neighbors and their neighborhood social environment (Wethington & Kavey, 2000). This is true despite provocative findings from the 1960s and 1970s that neighbors can be an important complement to family support systems (Cantor, 1979; Rosow, 1967). Neighborhood climate, defined as residents' neighborhood social environment, may be particularly important for older adults, who spend a good deal of time at home, in their neighborhoods (Horgas, Wilms, & Baltes, 1998). The neighborhood climate might include positive social interactions and helping behaviors toward the elder as well as unplanned or casual encounters with other neighborhood residents and an overall sense of attachment to the neighborhood. Further aspects of a positive neighborhood climate include having frequent visits and chats with nearby residents, making and maintaining acquaintances in the neighborhood, and being available to provide assistance in the event of a personal crisis. Positive neighborhood climates and related neighboring behaviors can therefore enhance the safety and health of older persons by improving access to critical goods and services such as grocery shopping, medical care, and household maintenance as well as providing a monitoring or “watching” function over the elder in her or his home. These prosocial behaviors may in turn increase the elder's independence, social involvement, and well-being (Wethington & Kavey, 2000). Increased frequency of positive contact with neighbors can result in increases in overall social support, satisfaction, and attachment to the neighborhood (Bell & Boat, 1957; Peirce, Frone, Russell, Cooper, & Mudar, 2000; Unger & Wandersman, 1982, 1985). Moreover, having many neighbors has been shown to be predictive of high levels of pereived support in community-dwelling older women (Magaziner & Cadigan, 1989). High levels of anticipated support from neighbors, in turn, have been associated with fewer functional limitations in older adults (Shaw, 2005). Indeed, neighborhood climate may be a potentially critical determinant of older people's health and mental health outcomes (Cantor, 1979; Rosow, 1967; Unger & Wandersman, 1982; Young, Russell, & Powers, 2004).

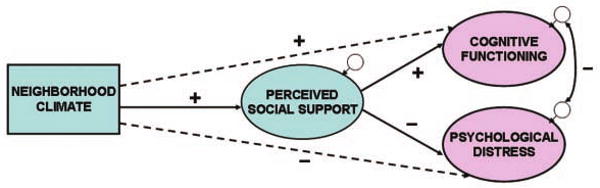

To our knowledge, no studies have simultaneously examined the relationships among neighborhood climate, social support, and older adults' mental health outcomes (e.g., psychological distress, cognitive functioning). Furthermore, we are not aware of any studies that have examined neighborhood climate or social interactions with neighbors in elderly Hispanics, who may be at particularly high risk for psychological distress and cognitive impairments because of social isolation, low socioeconomic status (SES), and residence in inner-city neighborhoods (Espino, Lichtenstein, Palmer, & Hazuda, 2001; Falcón & Tucker, 2000; Perrino, Brown, Mason, & Szapocznik, in press; Tang et al., 1998). At the same time, neighbors may be a particularly important source of support among some Hispanic subgroups (Bertera, 2003), which may in turn have an important impact on their level of psychological distress (Ostir, Eschbach, Markides, & Goodwin, 2003) and possibly their cognitive functioning (Espino et al., 2001). We theorize that neighborhood climate may achieve its effects on mental health through perceived social support—that is, having a more positive neighborhood social environment, through its impacts on higher perceived support, may in turn lead to reduced psychological distress and improved cognitive functioning. Moreover, we hypothesize that perceived support will mediate the relationship of neighborhood climate to each of psychological distress and cognitive functioning (see Figure 1). For the purposes of the present investigation, neighborhood climate reflects the broader social community of the neighborhood, including informal social ties in the neighborhood, sense of attachment to and satisfaction with the neighborhood, and frequency of giving and receiving assistance to and from neighbors, whereas perceived social support is operationalized as the elder's own evaluations of the perceived quality and quantity of her or his own direct personal experiences and interactions with others.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of the Relationship of Neighborhood Climate and Perceived Social Support to Cognitive Functioning and Psychological Distress.

Note: Dashed lines indicate hypothesized indirect relationships (i.e., perceived social support is hypothesized to mediate the relationship of neighborhood climate to each of (a) cognitive functioning and (b) psychological distress).

Perceived Social Support and Mental Health

Previous research has suggested that subjective evaluations of supportive social encounters may be more strongly related to mental health than are objective markers of social support (e.g., frequency of contact with others; Jang, Haley, Small, & Mortimer, 2002; Krause, 1995). That is, the perceived quality and quantity of social interactions may be more important than the actual support received by the elder (e.g., Fratiglioni, Wang, Ericsson, Maytan, & Winblad, 2000). The current literature suggests that the perception that others will be available to provide any needed assistance may reduce psychological distress by limiting the time spent worrying about life problems (Peirce et al., 2000) as well as increasing sense of control and reducing feelings of isolation and mistrust (Bisconti & Bergeman, 1999; Krause, 1993). In addition, perceived support may enhance emotional and cognitive functioning by promoting less threatening interpretations of adverse events and more effective coping strategies (Cohen & Wills, 1985) as well as possibly influencing physiological parameters known to be related to cognitive functioning and psychological distress including stress hormones such as cortisol (Cohen, 2004; Seeman, Lusignolo, Albert, & Berkman, 2001). The beneficial effects of social support for mental health may be particularly important in residents of low-SES neighborhoods, where it may serve to buffer the effects of neighborhood poverty and related environmental stressors such as crime, vandalism, and noise pollution (cf. Krause, 1998; Ostir et al., 2003).

Perceived support and psychological distress

Several studies have suggested that low satisfaction with the social support that one has received is an important predictor of psychological distress in older adults. For example, changes in older adults' satisfaction with social support were found to precede changes in depressive symptoms over time (Krause, Liang, & Yatomi, 1989). In addition, low satisfaction with social support has been shown to be a more important predictor of depression than more objective measures of support such as social network size (e.g., Jang et al., 2002). Other work has suggested that another aspect of perceived support— negative interactions—may also play a role in emotional functioning. Negative interactions in the form of unwanted support or conflict or demands from one's support providers (e.g., ineffective or excessive helping) may become a chronic source of stress for the elder, which can result in increased psychological distress (Krause & Rook, 2003).

Perceived support and cognitive functioning

Recent evidence suggests that perceived social support may play a role in elders' cognitive functioning. For example, a low level of perceived support has been found to be associated with concurrent cognitive impairment in community-dwelling elders (Ficker, MacNeill, Bank, & Lichtenberg, 2002). In addition, frequent satisfying contacts with children, relatives, or friends contributed to a formula that prospectively predicted decreased risk of dementia over 3 years (Fratiglioni et al., 2000). By contrast, few studies have examined the relationship of negative interactions to cognitive functioning (e.g., Seeman et al., 2001), although it has been suggested that conflictive and unpleasant interactions may potentially affect physiological parameters known to influence cognitive functioning, including stress hormones such as cortisol (McEwen, 1998).

In summary, substantial evidence exists that perceived social support may reduce psychological distress. In addition, evidence is emerging that perceived support may also have beneficial effects on cognitive functioning. However, given the evidence that social support may play an important role in mental health (e.g., Cohen, 2004), there has been surprisingly little research at the community level on predictors of social support (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001), including neighborhood social climate (cf. Wethington & Kavey, 2000). Ecodevelopmental theory predicts that social environmental contexts—such as neighborhood social climate and an individual's social support—may influence one another, and in turn these social context interactions are critical in understanding an individual's behavior and development (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999). Moreover, few studies have examined either the salutary effects of social support or predictors of support in Hispanic elders (e.g., Bertera, 2003), a growing minority group in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003).

The Present Investigation

The present study therefore examines the relationship of neighborhood climate (i.e., the neighborhood social environment) to urban Hispanic elders' social support, cognitive functioning, and psychological distress. This study focuses on neighborhood climate, as opposed to related concepts such as social capital (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001) or collective efficacy (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997), because neighborhood climate concerns the elder's own experiences with neighbors and perceptions of the neighborhood social environment, which is an important gap in the research literature (cf. Wethington & Kavey, 2000). In addition, this study also examines whether neighborhood climate predicts elders' perceptions of the individual social support that they receive and whether perceived social support in turn mediates the relationship of neighborhood climate to each of cognitive functioning and psychological distress (see Figure 1). To our knowledge, this is the first study that has examined the potential impacts of neighborhood climate on community-dwelling elders' cognitive and emotional functioning. Moreover, this study examines these relationships in a population-based study of urban older Hispanic immigrants in whom we previously documented a high rate (35%) of clinically relevant depressive symptoms (Perrino et al., in press). Finally, post hoc analyses explore possible gender differences in the relationship of neighborhood climate and perceived social support to Hispanic elders' mental health (cf. Antonucci et al., 2002; Zunzunegui et al., 2003).

Method

Setting

The study was conducted in East Little Havana in the city of Miami, Florida, which in 2002 was the poorest large city in the United States (defined as cities with populations greater than 250,000; U.S. Census Bureau, 2002). East Little Havana is more than 93% Hispanic, with a relatively high proportion of elderly adults (i.e., 19% of residents are 65 years of age or older) and more than 35% of residents living below the poverty level (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). The East Little Havana area includes 3,857 lots in 403 blocks and 40,865 residents (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000).

Research Design

This study is part of a larger population-based cohort study titled “The Hispanic Elders' Behavioral Health Study.” The study was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board. This work is part of a larger effort to assess the impact of neighborhood built (physical) and social environments on Hispanic elders' mental health.

Enumeration of Study Area

A door-to-door survey enumerated all 16,000 households in 403 blocks in East Little Havana, identifying 3,322 community-dwelling Hispanic immigrant older adults 70 years of age or older living on 302 blocks. A sample of older adults aged 70 and older was selected to maximize the likelihood of identifying an effect of the neighborhood social environment on social and mental health outcomes. Horgas and colleagues (1998) found that elders aged 70 and older spend approximately 80% of their time at home, in their neighborhoods. One Hispanic elder was randomly selected from each of the 302 blocks on which one or more elders lived. If she or he refused to participate or did not meet inclusion criteria, a second randomly selected elder was approached for consent to screen, and so on, until one elder in each of the blocks with elders had consented. Ultimately, the sample consisted of all blocks in which an elder who consented to participate met criteria. The final sample consisted of 273 elders (living in each of 273 blocks) who consented to participate in the full study and met criteria. (Of the 521 elders randomly selected for possible participation, 248 were lost for the following reasons: 95 refused, 87 moved away or could not be contacted after 11 home visits, 30 died, 24 did not meet other eligibility criteria, 10 had incorrect home addresses, and 2 moved to blocks from which elders were already sampled). As part of the larger study, elders completed three yearly assessments of neighborhood climate, social support, psychological distress, and cognitive functioning. The present analyses use baseline assessment data, with most baseline assessments completed in 2002-2003.

Participants

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were the following: (a) 70 years of age or older, (b) born in a Spanish-speaking country, (c) resident of East Little Havana, (d) lives in housing in which she or he can walk outside (this would exclude nursing homes or specialized locked housing units), (e) of sufficient health to go outside without physical assistance, based on reports from both the participant and a trained assessor; and (f) obtained a score of 17 or above on the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). The standard Mini-Mental State Examination cut point was lowered from 24 to 17 given concerns about this measure's lower sensitivity and specificity in detecting cognitive impairments among those with lower educational levels and possible bias with regard to language use and immigrant status (Mungas, Marshall, Weldon, Haan, & Reed, 1996; Ostrosky-Solis, López-Arango, & Ardila, 2000). For the 273 elders in the study, the mean Mini-Mental score was 24.8 (SD = 3.2). The baseline cohort of 273 elders was 59% female and was 86% Cuban and 6% Nicaraguan, and the remainder represented those from throughout Central and South America and Spain. Participants' mean age at baseline was 78.5 years (SD = 6.3) with 7.3 years of education (SD = 4.3) and with an average household income of $9,300 per year (SD = $4,550) and an average household size of 1.8 residents (SD = 1.1). In addition, 34% of participants were married and 7% were employed at baseline. Participants reported living in their home for an average of 13.7 years (SD = 11.3) and living in Little Havana for an average of 22.2 years (SD = 12.0) and living in the United States for an average of 28.6 years (SD = 12.4).

Measures

Neighborhood climate

Neighborhood climate was assessed by the Multidimensional Measure of Neighboring (Skjaeveland, Garling, & Maeland, 1996), a 14-item scale assessing positive and negative neighboring behavior, such as supportive acts of neighboring, neighborhood attachment, neighbor annoyance, and informal social ties. Higher scores indicate a more positive neighborhood social environment. Sample items include “If I need a little company, I can stop by a neighbor I know,” “I am strongly attached to this neighborhood,” “Noise that my neighbors make can occasionally be a big problem,” and “How many of your closest neighbors do you typically stop and chat with when you run into them?” This measure was translated into Spanish using the back translation and committee approach recommended by Kurtines and Szapocznik (1995). The alpha for the total scale score was .82.

Perceived social support measures

The Spanish-language versions of three indicators of perceived social support were drawn from Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (Wisniewski et al., 2003), based on items from Krause (1995; Krause & Markides, 1990). First, support satisfaction in the last month consists of three, 4-choice Likert-type items (e.g., “In general, how satisfied are you with the help you have received in the last month with transportation, household chores, gardening, and shopping?”). For this sample, alpha was .71. Second, support satisfaction in the last year consists of three, 3-choice Likert-type items (e.g., “During the past year, do you feel that this type of help was provided often enough, or do you wish it was given to you more often or less often?”). For this sample, alpha was .73. Third, negative interactions consists of four, 4-choice Likert-type items tapping negative social interactions during the past month (e.g., “In the past month, how often have others pried into your affairs?”). For this sample, alpha was .73.

Cognitive functioning measures

Cognitive functioning was assessed by three measures based on theoretical considerations (cf. Rapp et al., 2005). First, functional status was assessed by three of the skill domains from the Spanish-language version of the Direct Assessment of Functional Status: time orientation, communication skills, and financial skills (Loewenstein et al., 1989; Loewenstein et al., 1992). Adequate psychometric properties have been reported for these skill domains in Spanish-speaking and geriatric populations (Loewenstein et al., 1989; Loewenstein et al., 1992). In our present sample, the alpha reliability across all three scales was .79. Second, object memory was assessed by the Spanish-language version of the Fuld Object Memory Evaluation (Fuld, 1977; Loewenstein, Duara, Argüelles, & Argüelles, 1995). The Fuld is a measure of memory functioning that requires the participant to recall 10 common household objects (e.g., cup, ball). This study used a version of the Fuld that uses three learning trials and that shows adequate psychometric properties (Loewenstein et al., 2001). The score is the total number of targets recalled across the three learning trials. Third, tracking ability was assessed by the Color Trails Test, a culture-fair measure of nonlanguage general intellectual ability tapping tracking ability (i.e., visual attention, motor sequencing, and executive functioning; D'Elia, Satz, Uchiyama, & White, 1996). Color Trails has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of attention and executive functioning in geriatric and Spanish-speaking populations (D'Elia et al., 1996). The Color Trails measure used in the present study is the time to complete Trial 2 (in seconds).

Psychological distress measures

Psychological distress is measured in the present study by self-reported anxiety and depressive symptoms. Anxiety was measured using a Spanish-language 10-item short version of the Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory, taken directly from Spielberger's larger State-Trait Personality Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983). This measure has well-documented reliability and validity with the elderly (Carmin, Pollard, & Gillock, 1999) and Spanish-speaking populations (Novy, Nelson, Smith, Rogers, & Rowzee, 1995). For the present study, alpha was .89. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Spanish version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D; Carmin et al., 1999; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is a 20-item, four-position Likert-type scale of symptoms that place an individual at risk for clinical depression. The measure has demonstrated test–retest reliability and has been widely used in medical and epidemiological studies with elderly and Spanish-speaking populations (Carmin et al., 1999; Narrow, Rae, Moscicki, Locke, & Regier, 1990). The present analyses utilize the seven-item Depressive Affect subscale of the CES-D (e.g., “I felt sad”) because it may better reflect elders' underlying mood symptomatology while excluding somatic symptoms (e.g., difficulties eating and sleeping) that may be partly confounded with age and physical health in elderly populations (Fonda & Herzog, 2001). The CES-D Depressive Affect subscale had an alpha of .79 in the present sample.

Procedures

All participants were seen in their own home. Prior to the initial assessment, participants completed a consent form in which they consented to completing the Mini-Mental State Examination, for which they received $10. Those participants who met all eligibility criteria, including a Mini-Mental score of at least 17, were then fully enrolled into the study. These participants were asked to complete a second consent form in which they consented to participate in a total of four yearly assessments (baseline and 12, 24, and 36 months after baseline). Participants were informed that they would receive an additional $15 for completing the 3-hr battery at baseline (i.e., a total of $25 for baseline).

Analytic Strategy

Preliminary analyses were first conducted to examine zero-order (bivariate) correlations among the study variables as well as to examine the descriptive statistics for each variable. A single measurement model that consisted of four nonoverlapping constructs and their indicators (i.e., neighborhood climate, perceived social support, cognitive functioning, psychological distress) was then examined, with all correlations among latent constructs allowed to vary freely, as described by Kline (2005). A full measurement model was estimated containing all constructs, rather than a separate measurement model for each construct, because of problems of model identification that can result when only a small number of indicators are available for each construct (Kline, 2005). This full measurement model was estimated using AMOS 6 (Arbuckle & Wothke, 2005). AMOS uses a full information maximum likelihood algorithm (Arbuckle, 1996) to estimate missing data, which in the present data set represent less than 1.4% of cases for the primary analyses. Structural equation modeling of the relationship of neighborhood climate to perceived social support, cognitive functioning, and psychological distress was then conducted using AMOS, controlling for the relationship of age, education, and income to each of cognitive functioning and psychological distress. Structural equation modeling was chosen over other analytic techniques, such as measured-variable path analysis, because it allows for investigation of complex models including relations among observed and latent variables and corrects for measurement error, thereby allowing a more accurate test of meditational effects (Kline, 2005; McCoach, Black, & O'Connell, 2007). Further analyses then assessed whether perceived social support mediated the relationship between neighborhood climate and each of (a) cognitive functioning and (b) psychological distress. Mediation was tested using the asymmetrical distribution of products test (cf. MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002), which multiplies the unstandardized coefficients of the two paths that determine the mediating pathway and estimates a corresponding standard error. If the 95% confidence interval for this product does not include zero, then mediation is assumed. Finally, post hoc analyses were conducted in AMOS to identify possible gender differences in the model.

Results

Zero-Order Correlations Among the Study Variables

Table 1 shows the zero-order (bivariate) correlations among the measures of neighborhood climate, perceived social support, cognitive functioning, psychological distress, and demographic variables. As shown in Table 1, neighborhood climate had significant bivariate relationships in the hypothesized directions with all measures of perceived social support and psychological distress. In addition, neighborhood climate had a significant, positive association with one cognitive measure—functional status—and had a low but marginally significant positive correlation with a second cognitive measure—object memory (r = .12, p = .058). This suggests that more positive neighborhood climates may be associated with increased cognitive functioning.

Table 1. Zero-Order Correlations Among the Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Neigh. clim. | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Support (mo.) | .33** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3. Support (yr.) | .16** | .31** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4. Neg. interact. | −.16** | −.16** | −.30** | 1 | |||||||||

| 5. Funct. status | .15* | .00 | −.08 | −.02 | 1 | ||||||||

| 6. Obj. memory | .12 | .11 | −.08 | .02 | .44** | 1 | |||||||

| 7. Tracking (sec) | −.07 | .02 | .09 | .07 | −.55** | −.37** | 1 | ||||||

| 8. Anxiety | −.28** | −.16* | −.29** | .34** | −.15* | −.08 | .13* | 1 | |||||

| 9. Dep. sympt. | −.24** | −.16** | −.26** | .33** | −.21** | −.13* | .20** | .75** | 1 | ||||

| 10. Age | −.07 | .08 | .05 | .03 | −.31** | −.26** | .25** | .07 | .04 | 1 | |||

| 11. Education | –.08 | −.14* | .03 | −.03 | .25** | .08 | −.27** | −.03 | −.08 | −.12* | 1 | ||

| 12. Income | .05 | .09 | .00 | .05 | .05 | .09 | −.07 | −.13* | −.19** | .00 | .07 | 1 | |

| 13. Female | −.13* | .08 | −.05 | .08 | -.34** | −.07 | .17** | .21** | .23** | .19** | −.09 | −.14* | 1 |

Note: Neigh. climate = neighborhood climate; support (mo.) = support satisfaction (last month); support (yr.) = support satisfaction (last year); neg. interact. = negative interactions; funct. status = functional status; obj. memory = object memory; tracking (sec) = tracking ability (seconds); dep. sympt. = depressive symptoms.

p < .05.

p < .01.

With regard to the relationship of the demographic variables with the measures of neighborhood climate, cognition, and psychological distress, age was significantly correlated with all three cognitive measures in the direction of higher age being associated with worse cognitive functioning. In addition, education was significantly correlated with two of the cognitive measures, functional status and tracking ability, in the direction of higher education being associated with better cognitive functioning. Income was negatively associated with both of the psychological distress measures, suggesting that lower-income individuals reported greater psychological distress than did higher-income individuals. Female gender was negatively associated with neighborhood climate, suggesting that female respondents reported less positive neighborhood social environments than did male respondents. In addition, female gender was significantly correlated with two cognitive measures (i.e., functional status and tracking ability) in the direction of female gender being associated with worse cognitive performance. Finally, female gender was positively associated with both of the psychological distress measures, suggesting that the women reported more psychological distress than did the men. These findings of a possible gender difference in neighborhood climate, cognition, and psychological distress may reflect the fact that women in this sample were significantly older (M = 79.5 years, SD = 6.5) than were the men (M = 77.0 years, SD = 5.9), t(269) = 3.19, p = .002. In addition, the women in this sample reported having a mean yearly household income (M = $8,800, SD = $3,850) that was significantly lower than that reported by the men (M = $10,050, SD = $5,350), t(268) = 2.29, p = .023. Based on these bivariate findings, age, education, and income were covaried from cognitive functioning and psychological distress in the final structural equation model, and post hoc analyses were conducted to determine the impact of gender on the model.1

Descriptive Findings and Measurement Model for All Study Constructs

Table 2 shows the loadings and distributional statistics of the measured indicators in the full measurement model. This measurement model was conducted to ensure that the various indicators for each of perceived social support, cognitive functioning, and psychological distress could be collapsed into latent variables. A single analysis was conducted to estimate the measurement models for all constructs. Model fit for this confirmatory factor analysis was evaluated using standard fit indices in structural equation modeling—namely, the ratio of chi-square to the number of degrees of freedom (χ2/df) as well as the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The chi-square test indicates the amount of difference between expected and observed covariance matrices. A chi-square value close to zero indicates little difference between the expected and observed covariance matrices. The CFI test examines the specified model's degree of improvement over a null model with no paths or latent variables. The RMSEA index represents the extent to which the covariance structure specified in the model differs from the covariance structure observed in the data. The RMSEA index adjusts for sample size and model complexity, whereas the chi-square statistic does not and can indicate significant differences between the observed and model covariances even when such deviations are quite small (Kline, 2005). Therefore, we use the ratio of the chi-square statistic to the degrees of freedom as an index of model fit. Following Hu and Bentler (1999), χ2/df less than 3, CFI values of .90 or more, and RMSEA values of .06 or less were considered indicative of acceptable model fit. A RMSEA value of .08 represents the upper bound for acceptable model fit (MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996).

Table 2. Loadings and Distributional Statistics of Measured Indicators in the Full Measurement Model.

| Variable | Standardized Lambda Loading | Communality (h2) |

M (Observed) |

SD (Observed) |

Range (Observed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood climate | — | — | 47.73 | 8.71 | 18–62 |

| Perceived social support | |||||

| Support satisfaction (month) | .46 | .22 | 7.61 | 2.13 | 0–9 |

| Support satisfaction (year) | .61 | .37 | 5.66 | 0.89 | 3–9 |

| Negative interactions | −.50 | .25 | 1.11 | 2.05 | 0–11 |

| Cognitive functioning | |||||

| Functional status | .82 | .67 | 39.57 | 5.75 | 23–47 |

| Object memory | .53 | .29 | 20.91 | 4.86 | 2–30 |

| Tracking ability (sec) | −.69 | .47 | 207.81 | 96.00 | 70–642 |

| Psychological distress | |||||

| Anxiety | .86 | .74 | 20.33 | 8.10 | 10–40 |

| Depressive symptoms | .87 | .75 | 5.05 | 4.89 | 0–18 |

This full measurement model, consisting of neighborhood climate, perceived social support, cognitive functioning, and psychological distress, had an excellent fit to the data, χ2(22) = 38.577, p = .016; χ2/df = 1.754; CFI = .968, RMSEA = .053. As shown in Table 2, the factor loadings were in the acceptable to high range for all constructs (Comrey & Lee, 1992). With regard to correlations among the error terms of the latent constructs, there were significant correlations between neighborhood climate and perceived social support (φ = .41), between neighborhood climate and cognitive functioning (φ = .17), between neighborhood climate and psychological distress (φ = −.29), between perceived social support and psychological distress (φ = −.58), and between cognitive functioning and psychological distress (φ = −.26). The correlation between the error terms for perceived social support and cognitive functioning was not statistically significant (φ = −.04).

Full Structural Equation Model

The evaluation of the hypothesized model was conducted by adding directional paths from neighborhood climate to perceived social support, cognitive functioning, and psychological distress and from perceived social support to cognitive functioning and psychological distress. In addition, the error terms between cognitive functioning and psychological distress were allowed to correlate because the literature is unclear as to whether cognitive functioning affects psychological distress or psychological distress affects cognitive functioning (cf. Brown, Glass, & Park, 2002; Shifren, Park, Bennett, & Morrell, 1999). All variables showed sufficient variability to test the study hypotheses (see Table 2). Moreover, although there was some suggestion of skewness in the data (e.g., social support measures), this is relatively common in studies that measure social support and functioning in older adults (e.g., Krause, 1995), and we employed statistical methods (i.e., maximum likelihood method) that are relatively robust to non-normality (Lei & Lomax, 2005).

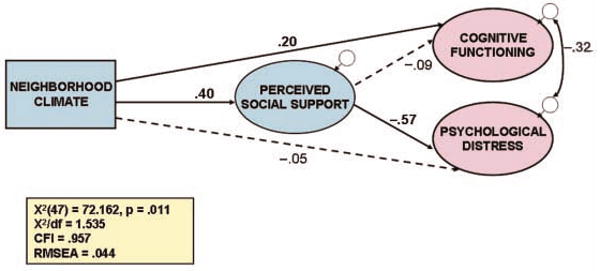

As shown in Figure 2, this structural equation model assessed the relationship of neighborhood climate to perceived social support, cognitive functioning, and psychological distress, after controlling for demographics (i.e., age, education, and income; not shown in Figure 2). The factor loadings for the constructs in this final model are approximately the same direction and magnitude as the factor loadings in the measurement model described above. Namely, the factor loadings were acceptable for the social support factor (standardized lambda [λ] values of .45, .60, and −.51 for support satisfaction in last month, support satisfaction in last year, and negative interactions, respectively) as well as for the cognitive functioning factor (λ = .81, .51, and −.69 for functional status, object memory and tracking ability in seconds, respectively). In addition, the factor loadings for psychological distress were quite high (λ = .84 and .89 for anxiety and depressive symptoms, respectively). The overall final model provided an excellent fit to the data, χ2(47) = 72.162, p = .011; χ2/df= 1.535; CFI = .957, RMSEA = .044. In this structural equation model, neighborhood climate had significant and positive direct relationships to perceived social support and cognitive functioning but did not have a significant direct relationship to psychological distress. Perceived social support, in turn, had a direct (and negative) significant relationship to psychological distress but did not show a significant direct relationship to cognitive functioning. In addition, there was a significant negative correlation between the error terms for cognitive functioning and psychological distress.

Figure 2. Structural Equation Model of the Relationship of Neighborhood Climate and Perceived Social Support to Cognitive Functioning and Psychological Distress, After Controlling for Age, Education, and Income.

Note: Dashed lines indicate statistically nonsignificant path coefficients. Standard fit indices suggest acceptable model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Legend abbreviations: X2 = χ2; CFI = comparative fix index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

With regard to the control demographic variables, not shown in Figure 2, age and education were significantly related to cognitive functioning (standardized path coefficients of γ = −.35 and γ = .28, respectively) but not to psychological distress (γ = .06 and γ = −.07, respectively). By contrast, income was significantly related to psychological distress (γ = −.17) but not to cognitive functioning (γ = .06). These results are consistent with previous findings that older and less educated individuals have poorer cognitive functioning than do younger and more educated individuals (e.g., Mungas et al., 1996) and that individuals with lower incomes may be at increased risk for psychological distress as compared to individuals with higher incomes (Perrino et al., in press).

Tests for Mediation

Analyses then examined whether the significant relationships of neighborhood climate to each of cognitive functioning and psychological distress as shown in Table 1 and the full measurement model were mediated by perceived social support. First examined was whether perceived social support mediated the relationship between neighborhood climate and cognitive functioning. This was done by multiplying the unstandardized path coefficient from neighborhood climate to perceived support by the unstandardized path coefficient from perceived support to cognitive functioning and estimating a corresponding standard error for this product term: The confidence interval for this initial test of mediation included zero (product of unstandardized paths = −.005; 95% confidence interval ranged from −.014 to .004). Because zero is included in the confidence interval, perceived social support does not appear to mediate the relationship between neighborhood climate and cognitive functioning. Second examined was whether perceived social support mediated the relationship from neighborhood climate to psychological distress. This was done by multiplying the unstandardized path coefficient from neighborhood climate to perceived support by the unstandardized coefficient from perceived support to psychological distress and estimating a corresponding standard error. The confidence interval for this test did not include zero (product of unstandardized paths = −.033; 95% confidence interval ranged from −.050 to −.016). Therefore, perceived social support can be said to mediate the relationship between neighborhood climate and psychological distress.

Further analyses examined the magnitude of the indirect relationship between neighborhood climate and psychological distress (operating through perceived social support). The indirect path coefficient operating through perceived social support was −.229, compared to the direct path coefficient of −.053. To compute the percentage of the total relationship between neighborhood climate and psychological distress that operated indirectly through perceived social support, the indirect path coefficient (−.229) was divided by the sum of the direct and indirect path coefficients (−.229 + −.053 = −.282). This analysis showed that perceived social support accounted for 81.2% of the total (direct and indirect) relationship between neighborhood climate and psychological distress.

Are There Gender Differences in the Full Model?

As a final post hoc analysis, a multigroup analysis in AMOS 6.0 (Arbuckle & Wothke, 2005) was conducted in which the final structural equation model was examined separately for each gender. This allowed the examination of whether the paths among the latent constructs varied significantly for men versus women. This multigroup analysis first compared an equal-loadings model in which the five paths among the latent constructs were set to be equal for the two groups (i.e., women and men) against an unrestricted-loadings model in which the five paths among the latent constructs were allowed to vary by gender. The equal-loadings model had an adequate fit to the data, χ2(125) = 201.392, p < .001; χ2/df = 1.611; CFI = .861, RMSEA = .047, although the CFI was lower than in the single group model (above). Moreover, the relations among the latent constructs (i.e., betas) were of approximately the same direction and magnitude as in the full single-group model (see Figure 2); that is, there were statistically significant paths from neighborhood climate to cognitive functioning (β = .18), from neighborhood climate to perceived social support (β = .41), and from perceived social support to psychological distress (β = −.58) but no significant paths from neighborhood climate to psychological distress (β = −.03) or from perceived social support to cognitive functioning (β = −.09). The unrestricted-loadings model also had an adequate fit to the data, χ2(120) = 195.342, p < .001; χ2/df = 1.628; CFI = .863, RMSEA = .048. However, this model did not have a significantly better fit than the equal-loadings model, Δχ2(5) = 6.050, p > .30, satisfying the criteria for metric invariance. The absence of a significant difference between the equal-loadings and unrestricted models suggests that the gender-specific models of neighborhood climate to perceived support and mental health do not behave differently from each other.

Discussion

The present study investigated the relationship of neighborhood climate (i.e., residents' neighborhood social environment) to perceived social support, cognitive functioning, and psychological distress in a community-based sample of older Hispanic immigrants residing in Miami, Florida. It was hypothesized that the relationship of neighborhood climate to each of (a) cognitive functioning and (b) psychological distress would be mediated by perceived social support.

The finding that neighborhood climate was associated with improved cognitive functioning and reduced psychological distress in this older Hispanic sample is consistent with prior suggestions that neighborhood social environments may be an important determinant of health and well-being in older adults (e.g., Cantor, 1979; Krause, 2003; Rosow, 1967; Unger & Wandersman, 1982). In addition, our findings that neighborhood climate was significantly related to perceived social support (cf. Magaziner & Cadigan, 1989; Wethington & Kavey, 2000) and that perceived social support was significantly related to reduced psychological distress (e.g., Antonucci et al., 2002; Krause et al., 1989) have been previously suggested in the literature. Moreover, our finding that neighborhood climate is indirectly related to psychological distress—through social support—is consistent with those of prior studies suggesting that the pathway between social relationships and depression is mediated by (emotional and instrumental) social support (e.g., Berkman & Glass, 2000; Harris, Brown, & Robinson, 1999). However, this is the first study of which we are aware to show that the relationship of neighborhood climate to psychological distress is mediated by perceived support.

It was somewhat surprising that perceived support was unrelated to cognitive functioning in the present study. However, this result has not been universally obtained in the literature. For example, at least one study has failed to find an association between perceived emotional support and cognitive functioning (e.g., Bassuk, Glass, & Berkman, 1999), and another study found that negative interactions were associated with better cognitive functioning rather than worse cognitive functioning (Seeman et al., 2001). It is possible that passive reception of emotional support may not be associated with cognitive functioning (Bassuk et al., 1999; Berkman, 2000; but for a different result, see, e.g., Seeman et al., 2001).

The absence of a relationship between perceived support and cognitive functioning in the present study suggests that the relationship of neighborhood climate to cognitive functioning may be mediated by mechanisms other than subjective evaluations of social support—possibly by social engagement and/or social integration with one's neighbors (cf. Wethington & Kavey, 2000). Substantial evidence suggests that an active, engaged lifestyle, involving participation in social activities with members of one's social network, may be associated with better mental and physical health outcomes in later adulthood (e.g., Rowe & Kahn, 1997). In particular, several recent studies have found a link between social engagement or social integration on one hand and cognitive functioning on the other hand. For example, Holtzman et al. (2004) reported that larger social networks protected against declines in cognitive functioning among older adults and that more frequent social contacts were positively related to cognitive functioning (see also Bassuk et al., 1999; Zunzunegui et al., 2003). Conversely, social isolation has been associated with future risk for dementia (Fratiglioni et al., 2000). It is therefore possible that any positive effects of neighborhood climate on cognitive functioning may occur through mechanisms other than social support; that is, a positive neighborhood social environment may have encouraged elders to engage socially with neighbors and therefore may have challenged them to communicate effectively and participate in complex interpersonal exchanges, which set into action the “use it” component of the “use it or lose it” phenomenon that has been shown to be important to successful aging (Rowe & Kahn, 1997; Seeman et al., 2001). Moreover, the present results are consistent with recent findings suggesting that social ties—including community social integration— may act as a stimulus for the brain through social activities and thus promote better cognitive functioning (e.g., Stine-Morrow, Parisi, Morrow, Greene, & Park, 2007; Zunzunegui et al., 2003).

Although gender was related to neighborhood climate in the bivariate analyses in the direction of more positive neighborhood climates reported by men than by women, our multigroup analysis suggested that there was no gender difference in the relationships from each of neighborhood climate and perceived support to mental health. Our finding that Hispanic women reported less positive neighborhood social environments than did Hispanic men in this study contrasts with the results of a previous study using this measure of neighborhood climate in a sample of primarily middle-aged adults in Norway, which found that women reported more positive neighborhood social environments than did men (Skjaeveland et al., 1996). These authors speculated that their result was because of women's greater preoccupation with child monitoring and a greater orientation to the outdoor neighborhood environment as compared to men. However, it is not clear that this would necessarily be the case for older adults, and we speculate that the Hispanic women in our sample may have reported a less positive neighborhood climate than the men because of their being older and having less income than their male counterparts and hence having fewer physical and financial resources to actively participate in neighborhood activities (Nakanishi & Tatara, 2000) as well as having greater concerns about their personal safety compared to men (Young et al., 2004). Moreover, it is possible that the fewer numbers of men in this age group may have resulted in men getting more attention than women. It is also possible that in a Latin culture in which men are less likely to be able to do things for themselves, the men attracted more positive interactions with neighbors because of their greater needs (Allen, Amason, & Holmes, 1998). Similarly, the lack of a gender difference in the relationship of neighborhood climate and social support to mental health was somewhat surprising given previous work suggesting that the influences of social support and social behaviors on mental health may vary for women versus men (e.g., Antonucci et al., 2002; Zunzunegui et al., 2003). It is possible that gender differences in the effects of social support on elders' mental health appear primarily in studies considering the stress-buffering effects of social support on elders' mental health (Antonucci et al., 2002) or other dimensions and situations under which social support operates, including the composition of the elder's social network (e.g., having a same-sex friend versus not having one; Schwartz, Meisenhelder, Ma, & Reed, 2003) or social support provided by the elder (e.g., Schieman & Meersman, 2004), rather than the main effects of perceived support as were tested in the present study.

Strengths

The present investigation has several strengths. First, this is the only study of which we are aware that has examined the relationship of residents' neighborhood social environment to older adults' social support, psychological distress, and cognitive functioning. Second, this is one of the first studies to have explored the social environment as a possible risk factor for mental health problems in Hispanic older adults residing in urban, low-SES neighborhoods (also see Espino et al., 2001; Ostir et al., 2003). Third, the present study used a population-based sample of independently living Hispanic elders in a poor community in Miami, Florida. Fourth, despite the rather restricted nature of this sample (i.e., primarily Cuban American older immigrants living in a single community in Miami), we identified substantial variability in neighborhood climate that was predictive of perceived support, cognitive functioning, and psychological distress in this sample. Fifth, this study examined the relationship of neighborhood climate and social support to a range of cognitive abilities (i.e., memory, tracking ability, and functional status). Finally, the present analyses controlled for key demographic variables (i.e., age, education, and income) that have been shown to be related to older adults' social behaviors and social supports (e.g., Glass, Mendes de Leon, Seeman, & Berkman, 1997; Kawachi & Berkman, 2001) as well as their psychological distress (e.g., Falcón & Tucker, 2000; Perrino et al., in press) and cognitive functioning (e.g., Cagney & Lauderdale, 2002; Mungas et al., 1996).

Limitations and Future Directions

However, the present study is not without its limitations. First, it is not possible to definitively establish causality with cross-sectional data (e.g., Does a positive neighborhood climate contribute to better mental health, or do more cognitively intact and less distressed older adults have a better neighborhood climate, including more positive interactions with their neighbors?). Future studies should therefore test these relationships longitudinally to determine directionality, which has important implications for interventions. Second, the present study investigated the relationship of neighborhood climate to one form of social support (i.e., perceived support), and thus future work should examine the relationship of neighborhood climate to other social support constructs, including specific forms of received support (i.e., instrumental, emotional, and informational support) as well as social support provided by the elder to others (e.g., Unger & Wandersman, 1985). Third, data are lacking in the present study on “third variables” such as health status or personality traits and attributional styles (e.g., neuroticism, pessimism) that may have impacts on both the social environment measures and the mental health measures. Such relationships should be examined in future studies. However, it should be noted that all participants in this study were able to make their way outside their home without physical assistance, and thus we attempted to minimize the impact of severe functional limitations on other study variables. Fourth, the generalizability of the present findings has yet to be determined (e.g., in Hispanic and non-Hispanic elderly populations outside Miami, including residents of communities that are not overwhelmingly Hispanic), and therefore these results await replication in other populations (cf. Barnes, 2003). Fifth, data are lacking in the present study on the specific sources of the social support received by our elders (i.e., Was support provided by neighbors vs. friends vs. family members?) as well as the specific types of support (i.e., both qualitative and quantitative measures) provided by each source and their respective contributions to elders' mental health. For instance, recent work on elders residing in Havana, Cuba, suggests that adult children may be an important source of social support for Cuban elders (Sicotte, Alvarado, León, & Zunzunegui, 2008). However, data are lacking in the present study on whether adult children live in the same home or neighborhood as the elder and on how often adult children interact with the elder. It is therefore unclear in the present study as to whether neighborhood climate, including neighbors' positive and supportive behaviors, is a mere adjunct or supplement to support that family members provide to the elder or whether this sample of urban elders, many of whom live alone, are relying on neighbors and other individuals outside the family for the majority of their support (cf. Magaziner & Cadigan, 1989). Such determinations may be vital for future intervention development. Thus, future work should examine the potentially salutary effects of neighborhood social environments on older adults' mental health, over and beyond the beneficial effects of social interactions and support provided by family members and friends and other individuals with whom the elder regularly interacts. In addition, future studies should more fully investigate longitudinal changes in older adults' interactions and social support from neighbors and other network members over time and how these relationships interact with one another as well as with older adults' health and well-being over time (cf. Barnes, 2003; Fratiglioni et al., 2000; Glass et al., 1997). Nonetheless, despite the above limitations in the present work, we found that neighborhood climate was significantly and moderately associated with both psychological distress and cognitive functioning and that perceived support accounted for more than 80% of the relationship between neighborhood climate and psychological distress, the first study of which we are aware that has examined this relationship.

Future research should also examine the various ways that formal and informal neighborhood ties and social behaviors may help to expand the often-limited options and resources of elderly residents in poor urban neighborhoods (Barnes, 2003). More specifically, there is a great need for multilevel analyses examining neighborhood and individual differences in the impacts of social behaviors on older adults' mental and physical health outcomes. Such studies are needed so that we may more clearly understand the mechanisms shaping socialization and health in neighborhoods, including neighborhood climate as well as the related concepts of social capital and collective efficacy and sense of belonging to a neighborhood, which have also been shown to influence health (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001; Sampson et al., 1997; Young et al., 2004), and devise appropriate interventions wherever necessary. Moreover, much more research is needed on the impacts of social and physical environments on the health and well-being of older adults from distinct racial and ethnic minority groups that are understudied and yet compose increasing proportions of the elderly population in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003). In particular, different Hispanic subgroups such as Cuban Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Mexican Americans came to the United States under quite different historical and economic circumstances and may therefore perceive and utilize their neighborhoods very differently (cf. Barnes, 2003; Krause, 2003). It is particularly critical that researchers identify the determinants of neighborhood processes and health in distinct subpopulations of minority elders, particularly given recent work suggesting that ethnic and racial disparities in health and well-being may be mediated by neighborhood conditions, including the density of Hispanic immigrants living within the neighborhood (e.g., Espino et al., 2001). Moreover, other recent work has suggested that Hispanic elders may have less social support than other older ethnic groups, which may have negative implications for their health and well-being (e.g., Bertera, 2003). Thus, substantial research is needed to determine who is at greatest need for interventions and to identify the most appropriate interventions for particular subgroups of elders (cf. Kawachi & Berkman, 2001). This may be particularly important given other work suggesting that social isolation can lead to psychological distress and cognitive impairment over time (e.g., Bassuk et al., 1999; Roberts, Kaplan, Shema, & Strawbridge, 1997), which can in turn hasten relocation to institutional settings (e.g., Russell, Cutrona, de la Mora, & Wallace, 1997). Based on this work, mental health professionals should identify culturally appropriate mechanisms for strengthening traditional community and family sources of support by providing opportunities for reducing personal, family, and social isolation. The impact of neighborhood social climates on social support, social behaviors, and health in elderly residents merits further research and may provide a base for interventions that may help older adults to “age in place” in their homes, without need for institutionalization.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant MH 63709 (principal investigator [PI]: J. Szapocznik; co-PI: A. Spokane) and National Institute on Aging Grant AG 27527 (PI: J. Szapocznik; co-PI: S. Brown). We thank Daniel Feaster and Seth Schwartz for their statistical assistance and Rosa Verdeja, Monica Zarate, Tatiana Clavijo, Aleyda Marcos, Fred Newman, and Pat Thomas for their assistance with the conduct of the study. We thank Tatiana Perrino for her helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Footnotes

Two additional sociodemographic variables were considered as possible control variables in the present analyses: (a) marital status and (b) time spent living in one's home (in months). However, marital status had only one significant bivariate correlation with the main analytic variables of interest: depressive symptoms (r = −.14, p = .022; not shown in Table 1). In addition, time in home had no significant bivariate correlations with any of the main analytic variables of interest. Furthermore, when we attempted to include marital status and time in home as covariates in the full structural equation model shown in Figure 2 (i.e., along with age, education, and income), neither marital status nor time in home were significantly associated with any of the latent variables in the model, and therefore these two variables were dropped from the final model.

Contributor Information

Scott C. Brown, University of Miami, Florida.

Craig A. Mason, University of Maine, Orono.

Arnold R. Spokane, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Maria Cristina Cruza-Guet, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Barbara Lopez, University of Miami, Florida.

José Szapocznik, University of Miami, Florida.

References

- Allen MW, Amason P, Holmes S. Social support, Hispanic emotional acculturative stress, and gender. Communication Studies. 1998;49(2):139. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Lansford JE, Akiyama H, Smith J, Baltes M, Takahashi K, et al. Differences between men and women in social relations, resource deficits and depressive symptomatology during later life in four nations. Journal of Social Issues. 2002;58(4):767–783. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. AMOS release 6.0 [Computer software] Chicago: Smallwaters; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes SL. Determinants of individual neighborhood ties and social resources in poor urban neighborhoods. Sociological Spectrum. 2003;23:463–497. [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk SS, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999;131(3):165–173. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell W, Boat MD. Urban neighborhoods and informal social relations. American Journal of Sociology. 1957;62:391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF. Which influences cognitive function: Living alone or being alone? Lancet. 2000;355:1291–1292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T. Social integration, social networks: Social support and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 137–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bertera EM. Psychosocial factors and ethnic disparities in diabetes diagnosis and treatment among older adults. Health & Social Work. 2003;28(1):33–42. doi: 10.1093/hsw/28.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisconti TL, Bergeman CS. Perceived social control as a mediator of the relationships among social support, psychological well-being, and perceived health. The Gerontologist. 1999;39(1):94–103. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SC, Glass JM, Park DC. The relationship of pain and depression to cognitive function in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Pain. 2002;96:279–284. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagney KA, Lauderdale DS. Education, wealth, and cognitive function in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2002;57B(2):163–172. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.2.p163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor MH. Neighbors and friends: An overlooked resource in the informal support system. Research on Aging. 1979;1(4):434–463. [Google Scholar]

- Carmin CN, Pollard CA, Gillock KL. Assessment of anxiety disorders in the elderly. In: Lichtenberg PA, editor. Handbook of assessment in clinical gerontology. New York: John Wiley; 1999. pp. 59–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist. 2004;59(8):676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comrey AL, Lee HB. A first course in factor analysis. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- D'Elia LF, Satz P, Uchiyama CL, White T. Color Trails Test professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Espino DV, Lichtenstein MJ, Palmer RF, Hazuda HP. Ethnic differences in Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores: Where you live makes a difference. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49(5):538–548. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcón LM, Tucker KL. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among Hispanic elders in Massachusetts. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2000;55B(2):S108–S116. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.2.s108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficker LJ, MacNeill SE, Bank AL, Lichtenberg PA. Cognition and perceived support among live-alone urban elders. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2002;21(4):437–451. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonda SJ, Herzog AR. Patterns and risk factors of change in somatic and mood symptoms among older adults. Annals of Epidemiology. 2001;11(6):361–368. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratiglioni L, Wang HX, Ericsson K, Maytan M, Winblad B. Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: A community-based longitudinal study. Lancet. 2000;355:1315–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuld PA. Fuld Object Memory Evaluation manual. Wood Dale, IL: Shoelting Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, Mendes de Leon CF, Seeman TE, Berkman LF. Beyond single indicators of social networks: A Lisrel analysis of social ties among the elderly. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44(10):1503–1517. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T, Brown GW, Robinson R. Befriending as an intervention for chronic depression among women in an inner city: I. Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;174:219–224. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman RE, Rebok GW, Saczynski JS, Kouzis AC, Doyle KW, Eaton WW. Social network characteristics and cognition in middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2004;59B(6):278–284. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.6.p278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgas AL, Wilms HU, Baltes MM. Daily life in very old age: Everyday activities as expression of successful living. The Gerontologist. 1998;38:556–568. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.5.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria in fix indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Haley WE, Small BJ, Mortimer JA. The role of mastery and social resources in the associations between disability and depression in later life. The Gerontologist. 2002;42(6):807–813. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Neighborhood deterioration and social isolation in later life. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1993;36(1):9–38. doi: 10.2190/UBR2-JW3W-LJEL-J1Y5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Negative interaction and satisfaction with social support among older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences. 1995;50B(2):59–73. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.2.p59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Neighborhood deterioration, religious coping, and changes in health during late life. The Gerontologist. 1998;38(6):653–664. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.6.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Neighborhoods, health, and well-being. In: Wahl HW, Scheidt RJ, Windley PG, editors. Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics, Vol 23. Aging in context: Socio-physical environments. New York: Springer; 2003. pp. 223–249. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Liang J, Yatomi N. Satisfaction with social support and depressive symptoms: A panel analysis. Psychology and Aging. 1989;4(1):88–97. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Markides K. Measuring social support among older adults. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1990;30:37–53. doi: 10.2190/CY26-XCKW-WY1V-VGK3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Rook KS. Negative interaction in late life: Issues in the stability and generalizability of conflict across relationships. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2003;58B(2):88–99. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.p88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtines WM, Szapocznik J. Cultural competence in assessing Hispanic youths and families: Challenges in the assessment of treatment needs and treatment evaluation for Hispanic drug abusing adolescents (Report 95-3908) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei M, Lomax RG. The effect of varying degrees of nonnormality in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2005;12(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein DA, Amigo E, Duara R, Guterman A, Hurwitz D, Berkowitz N, et al. A new scale for the assessment of functional status in Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. Journal of Gerontology. 1989;44:114–121. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.4.p114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein DA, Ardila A, Roselli M, Hayden S, Duara R, Berkowitz N, et al. A comparative analysis of functional status among Spanish and English-speaking patients with dementia. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1992;47:389–394. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.p389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein DA, Argüelles T, Acevedo A, Freeman RQ, Mendelssohn E, Ownby RL, et al. The utility of a modified object memory test in distinguishing between different age groups of Alzheimer's disease patients and normal controls. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2001;7(3):317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein DA, Duara R, Argüelles T, Argüelles S. Use of the Fuld Object-Memory Evaluation in the detection of mild dementia among Spanish- and English-speaking groups. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1995;3(4):300–307. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199503040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaziner J, Cadigan DA. Community resources and mental health of older women living alone. Journal of Aging and Health. 1989;1(1):35–49. doi: 10.1177/089826438900100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoach DB, Black AC, O'Connell AA. Errors of inference in structural equation modeling. Psychology in the Schools. 2007;44(5):461–470. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(3):171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungas D, Marshall SC, Weldon M, Haan M, Reed BR. Age and education correction of Mini-Mental State Examination for English and Spanish-speaking elderly. Neurology. 1996;46:700–706. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi N, Tatara K. Correlates and prognosis in relation to participation in social activities among older people living in a community in Osaka, Japan. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 2000;6(4):299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Narrow WE, Rae DS, Moscicki EK, Locke BZ, Regier DA. Depression among Cuban Americans: The Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1990;25:260–268. doi: 10.1007/BF00788647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novy DM, Nelson DV, Smith KG, Rogers PA, Rowzee RD. Psychometric comparability of the English and Spanish language versions of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17(2):209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ostir GV, Eschbach K, Markides KS, Goodwin JS. Neighborhood composition and depressive symptoms among older Mexican Americans. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:987–992. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.12.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrosky-Solis F, López-Arango G, Ardila A. Sensitivity and specificity of the Mini-Mental State Examination in a Spanish-speaking population. Applied Neuropsychology. 2000;7:25–31. doi: 10.1207/S15324826AN0701_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce RS, Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML, Mudar P. A longitudinal model of social contact, social support, depression, and alcohol use. Health Psychology. 2000;19(1):28–38. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Brown SC, Mason CA, Szapocznik J. Depressive symptoms among urban Hispanic older adults in Miami: Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. Clinical Gerontologist. doi: 10.1080/07317110802478024. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp MA, Beeri MS, Schmeidler J, Sano M, Silverman JM, Haroutunian V. Relationship of neuropsychological performance to functional status in nursing home residents and community-dwelling older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(6):450–459. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.6.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ, Strawbridge WJ. Does growing old increase the risk for depression? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(10):1384–1390. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosow I. Social integration of the aged. New York: Free Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe JR, Kahn RL. Successful aging. The Gerontologist. 1997;37(4):433–440. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW, Cutrona CE, de la Mora A, Wallace RB. Loneliness and nursing home admission among rural older adults. Psychology & Aging. 1997;12(4):574–589. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.4.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Meersman SC. Neighborhood problems and health among older adults: Received and donated support and the sense of mastery as effect modifiers. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59:S89–S97. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C, Meisenhelder JB, Ma Y, Reed G. Altruistic social interest behaviors are associated with better mental health. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(5):778–785. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000079378.39062.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Lusignolo TM, Albert M, Berkman L. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Health Psychology. 2001;20(4):243–255. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BA. Anticipated support from neighbors and physical functioning during later life. Research on Aging. 2005;27(5):503–525. [Google Scholar]

- Shifren K, Park DC, Bennett JM, Morrell RW. Do cognitive processes predict mental health in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis? Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1999;22(6):529–547. doi: 10.1023/a:1018782211847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicotte M, Alvarado BE, León EM, Zunzunegui MV. Social networks and depressive symptoms among elderly women and men in Havana, Cuba. Aging & Mental Health. 2008;12(2):193–201. doi: 10.1080/13607860701616358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjaeveland O, Garling T, Maeland JG. A multidimensional measure of neighboring. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:413–435. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene PR, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults (STAIS-AD) manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow EAL, Parisi JM, Morrow DG, Greene J, Park DC. An engagement model of cognitive optimization through adulthood. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62:62–69. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.special_issue_1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz M, Hartel CR, editors. Drug abuse: Origins and interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, Bell K, Gurland B, Lantigua R, et al. The APOE-ε4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, Whites, and Hispanics. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:751–755. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.10.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger DG, Wandersman A. Neighboring in an urban environment. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1982;10(5):493–509. doi: 10.1007/BF00894140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger DG, Wandersman A. The importance of neighbors: The social, cognitive, and affective components of neighboring. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1985;13(2):139–169. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. United States Census 2000. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Percent of people below poverty level. 2002 Retrieved August 14, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/acs/www/Products/Ranking/2002/pdf/R01T160.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Census bureau releases population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. 2003 Retrieved August 14, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/2003/cb03-16.html.

- Wethington E, Kavey A. Neighboring as a form of social integration and support. In: Moen P, Pillemer K, editors. Social integration in the second half of life. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2000. pp. 190–210. [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski SR, Belle SH, Coon DW, Marcus SM, Ory MG, Burgio LD, et al. The Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (REACH): Project design and baseline characteristics. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18(3):375–384. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]