Abstract

Using a discrete trials (DT) procedure we have previously shown that rats exhibit variations in their pattern of cocaine self-administration relative to the time-of-day, often producing a daily rhythm of intake in which the majority of infusions occur during the dark phase of the light cycle. We have sought to determine if cocaine self-administration demonstrates free-running circadian characteristics when held under constant lighting conditions in the absence of external environmental cues. Rats self-administering cocaine (1.5 mg/kg/infusion) under a DT3 procedure (three trials per hour) were kept in constant dim (<5lux, DIM) conditions and the pattern of intake analyzed for free-running behavior. We show that cocaine self-administration has a period length (TAU) of 24.13 ± 0.07 hours in standard 12-hr light-dark conditions, which is maintained for at least five days in constant dim conditions. With longer duration DIM exposure cocaine self-administration free-runs with a TAU of approximately 24.92 ± 0.16 hours. Exposure to constant light conditions (1000lux, LL) lengthened TAU to 26.46 ± 0.23 hours; this was accompanied by a significant decrease in total cocaine obtained during each period. The pattern of cocaine self-administration, at the dose and availability used in this experiment, is circadian and is likely generated by an endogenous central oscillator. The DT procedure is therefore a useful model to examine the substrates underlying the relationship between circadian rhythms and cocaine intake.

Keywords: cocaine, self-administration, circadian rhythm, free-run, tau

Introduction

Clinical studies indicate an interaction between circadian rhythms and drug abuse. Substance abuse is associated with a disruption in the circadian manifestation of several physiological functions including sleep, body temperature, and hormone levels (Jones et al. 2003; Mukai et al. 1998; Spanagel et al. 2005; Wasielewski and Holloway 2001). Sleep in particular has been linked to several addiction phenomena. Individuals with sleep disturbances and shift-workers are more likely to abuse drugs (Teplin et al. 2006; Trinkoff and Storr 1998). Abstinence and withdrawal often produce profound disruptions in sleep patterns, including insomnia, which could potentially contribute to relapse (Brower et al. 2001; Budney et al. 1999; Jones et al. 2003; Pace-Schott et al. 2005; Ziedonis et al. 2005). Time of day may also influence the sensitivity to abused substances. For example, it is well established that overdose presentations in the emergency room peak during the late afternoon to early evening hours (Morris 1987; Raymond et al. 1992). Evidence exists that the diurnal peak in opiate overdose in particular results from enhanced sensitivity to the drug during this time period and does not correlate with social factors such as increased access during night time hours (Gallerani et al. 2001; Manfredini et al. 1994; Raymond et al. 1992). While there is a clear correlation between time-of-day and drug abuse, it is not known if this relationship is related to the acute affects of the light:dark cycle or due to an underlying circadian rhythm influencing distinct temporal aspects of drug taking.

Recent studies have demonstrated that molecular and anatomical manipulations that alter circadian oscillations also affect sensitivity to drugs of abuse in animal models. For example, mutations of some clock genes in mice lead to increased sensitivity to cocaine-induced hyperlocomotion and conditioned place preference (CPP), a behavioral measure in which an animal spends more time in an environment associated with the drug (Abarca et al. 2002; McClung et al. 2005). These mutants also display enhanced dopaminergic activity within the mesolimbic system (Roybal et al. 2007), which is essential to the reinforcing effects of psychostimulants (Lyness et al. 1979; Roberts et al. 1977). Neurons in these regions also express clock genes and it has been shown that several proteins related to dopaminergic transmission (e.g. dopamine receptors, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the dopamine transporter (DAT)) are expressed in a circadian or diurnal fashion (Akhisaroglu et al. 2005; Sleipness et al. 2007b). Therefore specific neural and molecular substrates appear to be responsible for the circadian influences on drug reinforcement.

Cocaine addiction is often thought of as a process that starts with sporadic, recreational drug use that transitions to a state of consistent drug seeking and taking behaviors punctuated by periods of intense binging (Roberts et al. 2007). The behaviors associated with drug addiction and dependence can be studied in animals using self-administration models, in which a subject is implanted with an intravenous catheter that is connected to a drug syringe in a pump. The animal can control drug intake by pressing a lever to activate the pump. Different behavioral aspects of human drug addiction can be modeled by changing the parameters under which the drug is available, such as increasing the response requirement to obtain a drug infusion (the cost), or limiting the animal’s access to the lever to certain times of the day. For example, rats will readily binge on cocaine to the point of lethal overdose if allowed unlimited 24-hour access (Bozarth and Wise 1985). However, under restricted access conditions, in which the number of infusions is limited during a 24-hour period, cocaine binges may be absent and cocaine taking can occur in a much more regulated, spaced pattern (Roberts and Andrews 1997).

Our laboratory has demonstrated that there is a bidirectional relationship between cocaine self-administration and daily rhythms; thus, while the time of day can influence cocaine intake, high levels of cocaine intake - either through larger doses or more access - can also disrupt or mask the daily fluctuations in drug self-administration (Roberts et al. 2002). Cocaine self-administration has been shown to fluctuate across the light:dark cycle when intake of drug is limited through the use of a discrete trials procedure (Roberts et al. 2002). For example, a clear daily rhythm of cocaine self-administration is observed when access is restricted to 3 discrete trials/hour (DT3, 1.5 mg/kg/inj). The probability of a rat self-injecting an infusion is very high during the dark (active) phase and very low during the light phase. Intake of cocaine rises dramatically as the number of trials/hour is increased. Indeed, with 5 trials per hr (DT5), rats will ‘binge’, taking drug at every opportunity for several days in a row leading to a loss of apparent daily rhythmicity (Roberts et al. 2002). The data demonstrate that when hourly access to cocaine is increased, daily control is diminished and an extended binge pattern dominates.

Others have also examined the influence of cocaine intake on the circadian expression of some physiological parameters using self-administration protocols that result in “binging”. For example, it has been shown that escalating patterns of cocaine intake have a profound effect on the diurnal expression of locomotor activity and core body temperature (Tornatzky and Miczek 1999; 2000). Because of their short duration (72 hours or less) it was not possible to confirm a direct circadian influence in these studies. Furthermore, the protocols used to produce these “binges” result in large amounts of cocaine intake. Yet, the acute pharmacological effects of cocaine, which include alterations in body temperature and hyperlocomotion (Ansah et al. 1996), make it impossible to determine if the drug is altering circadian rhythms or just masking their presence.

Thus while there is evidence that cocaine self-administration follows a daily rhythm under controlled, restricted access conditions, and that acute cocaine “binges” can disrupt circadian controlled physiological processes, it is not known if cocaine self-administration rhythms are produced by a circadian process. A rhythm is considered circadian if it persists under constant conditions in the absence of external cues and can be entrained by environmental signals such as light. If cocaine self-administration is truly governed by an endogenous circadian oscillator, we predict that: 1) cocaine self-administration will persist in the absence of light:dark cues and 2) it’s period should be influenced by light intensity. Furthermore, we hypothesize that constant light conditions will disrupt the rhythmicity of endogenous oscillators and produce an arrhythmic pattern of cocaine self-administration. In the first experiment, we tested the hypothesis that the circadian pattern of cocaine self-administration would persist in constant dim lighting conditions. The 24-hr pattern of cocaine intake under a DT3 schedule was determined for five days in constant dim conditions (i.e. without a light/dark cycle). This was followed by a second, more extensive experiment, to establish if cocaine self-administration would free-run under extended dim conditions, and finally how constant light will affect the pattern of cocaine intake. To our knowledge, this is the first analysis of circadian parameters in a long-term, 24-hour self-administration experiment under constant lighting conditions and is the first demonstration that the motivation to obtain cocaine persists and free-runs in constant dim conditions.

Methods

Subjects

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, IN) weighing 275–300 g at the start of the study were used in all experiments. Animals were allowed at least three days to acclimate to the vivarium where they were maintained in a 12-h light/dark (LD) cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All research was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Wake Forest University, conducted in accordance with the guidelines set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996) and according to accepted principles and standards for biological rhythm research (Portaluppi et al. 2008).

Surgery, apparatus and measurements

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg, IP) and xylazine (8 mg/kg, IP) and implanted with a chronically indwelling Silastic™ jugular cannula that exited through the dorsal surface just posterior to the scapulae. Following surgery each animal was placed in an individual chamber 30 × 30 × 30 cm2. The cannula was contained within a flexible tether, which extended from the animal through a small opening at the top of the cage to a counterbalanced swivel allowing free movement throughout the chamber. Rats were allowed four days of recovery during which the catheter was flushed daily with heparinized saline. The rats were then given access to a response lever during daily sessions starting at 10:00 h. and initially trained under a fixed ratio schedule of reinforcement where one press of the lever (FR1) activated an infusion pump that delivered 1.5 mg/kg of cocaine. At the same time a yellow stimulus light was activated, which signaled a 20 second time out period during which the lever was retracted. Sessions were terminated after a total of 20 injections were attained or a maximum of 6 hours was reached. Once all subjects had achieved stable self-administration (regular inter-infusion intervals and five consecutive days of 20 infusions/session) the schedule was switched to DT3 under LD conditions. Under the DT3 schedule, a discrete 10 min trial is initiated every 20 minutes for the entire experiment, 24-hour/day. During each 10 min trial a single lever response results in an infusion of cocaine (1.5 mg/kg/inj), followed by the immediate retraction of the lever and termination of the trial. A trial is initiated at the 00:00 h, 00:20 h, and 00:40 h minute of each hour, with 10 min time outs scheduled at 00:10 h, 00:30 h, and 00:50 h. If the lever is not pressed during the trial, it will retract when the 10 min has elapsed followed by a 10 min time out before the next discrete trial is initiated. If the lever is pressed, the remaining time of the trial is added to the subsequent 10 min time out. After the circadian assessments, the animals were placed back in standard LD conditions and tested under an FR1 schedule, in which stable self-administration indicates that the patency of the catheter is intact. Since it is very difficult to determine exactly when a catheter becomes blocked, or partially blocked, only those animals that still had patent catheters at the end of the study were included in the analysis.

Two experiments were conducted in this study, in the first experiment five animals were trained and assessed in DIM conditions for seven days. In the second experiment, ten animals were continuously maintained on the DT3 schedule in DIM for a period up to 21 days followed by seven days of LL. The longer experiment was particularly arduous, as we could not flush the catheters with heparinized saline to help maintain patency since this would administer a bolus of cocaine which itself, could serve as a zeitgeber.

Lighting conditions

Illumination during the light phase was supplied by standard overhead fluorescent lights, which produced a range of luminescence from 600 to 1400 lux at the level of the cages. During the dark phase of the LD cycle, the fluorescent lights were turned off and low-intensity white night lights producing less than 2 lux were used. After collecting 11 days of baseline data in LD conditions, the overhead fluorescent lights were turned off and red night lights, producing less than 2 lux, remained on continuously (DIM). Red stimulus response lights were used in the behavioral chamber during this period. The stimulus lights produced less than 1 lux of red light at the level of the rat’s head when activated. The design of the experimental chambers, which have solid metal sides facing the night lights, restricted total red illumination within the chamber to less than 1 lux, regardless of whether the red stimulus light was activated or not. Data were collected in all DIM conditions for the next 21 days. Thereafter the fluorescent lights were turned on and additional lights were added to ensure approximately 1000 lux exposure. Light exposure was maintained for the entire 24-hour period (LL). Rats were maintained in LL for seven days. Following completion of the study, the rats were switched to standard LD conditions and catheter patency was assessed under an FR1 schedule.

Data Analysis

Cocaine self-administration data were collected at 20 min intervals and analyzed using ClockLab Analysis software (ver. 2.63, Actimetrics Software, Wilmette, IL) run under Matlab (2008a, ver 7.6.0.324, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). Estimates of cocaine injection onset, offset and length of cocaine injection periods (period between onset and offset; alpha) were made using least squares sine curve fitting. Period length (TAU) was determined using the Chi-Square periodogram function of ClockLab as originally described (Sokolove and Bushell 1978). In addition, the duration of self-administration (alpha) was determined in both DIM and LL conditions. Data are presented as the means ± standard error of mean (SEM). For statistical comparison, data were analyzed using either Student’s t-test or ANOVA (one-way or repeated measures) followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism for the Macintosh (ver. 5.0a, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05.

Results

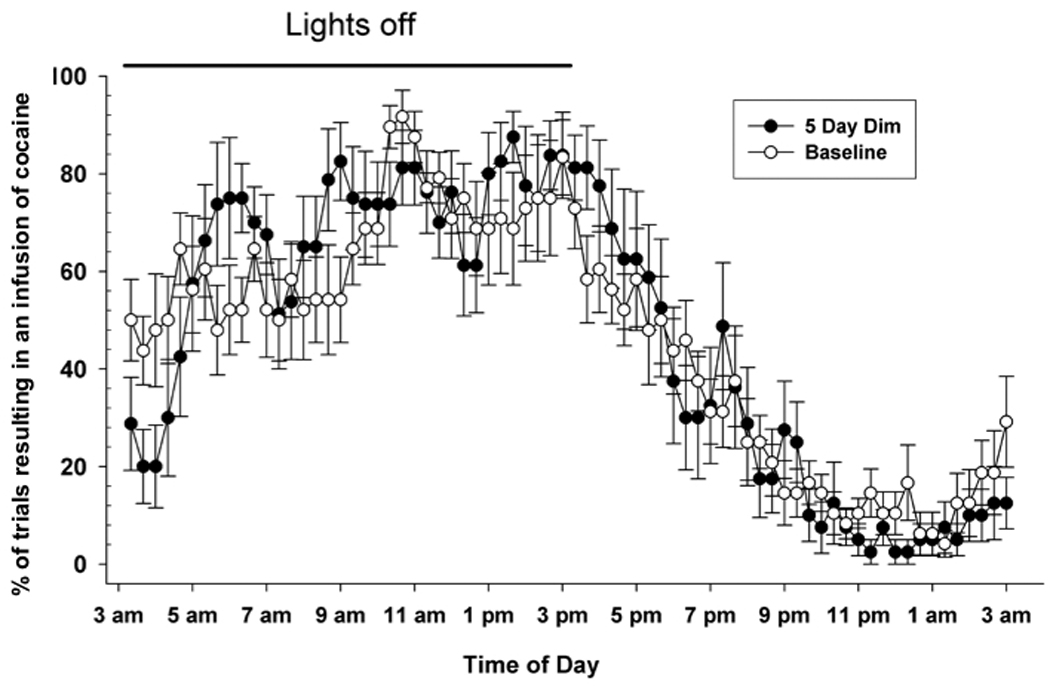

The first experiment was conducted to determine if the daily rhythm of cocaine self-administration persisted in the absence of varying environmental light cues. Five rats were trained to self-administer cocaine using a DT3 schedule under standard LD conditions for 7 days. Thereafter the rats were maintained in constant DIM for five days. The probability of obtaining an infusion of cocaine was determined for each discrete trial in both LD and DIM conditions and the data collapsed over a single 24 h period. Figure 1 shows that rats maintained a cyclic daily pattern of self-administration for at least five days in both LD and DIM conditions. Under LD, the number of cocaine infusions administered during the 12h dark phase of the LD cycle was significantly greater than during the 12h light phase (24.7 ± 1.5 vs. 10.8 ± 0.9, t10 = 8.1, p < 0.0001). Under DIM conditions the total number of cocaine injections self-administered per day was similar to that observed in LD conditions (38.0 ± 1.4 vs. 35.9 ± 1.5, respectively, p > 0.05). ClockLab analysis of the 5 days of DIM, revealed a period length slightly longer than under LD (24.22 ± 0.2h vs. 23.73 ± 0.12h), but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.08).

Figure 1.

Propensity to self-administer cocaine during each trial of the 24-hour time period under different lighting conditions. The means ± SEM for each trial were calculated from animals exposed to five days of standard 12:12 LD conditions (baseline) followed by continuous DIM conditions (5 day dim). The black bar represents the time of the dark phase during the LD portion of the experiment. The data produced under both lighting conditions do not significantly differ from each other.

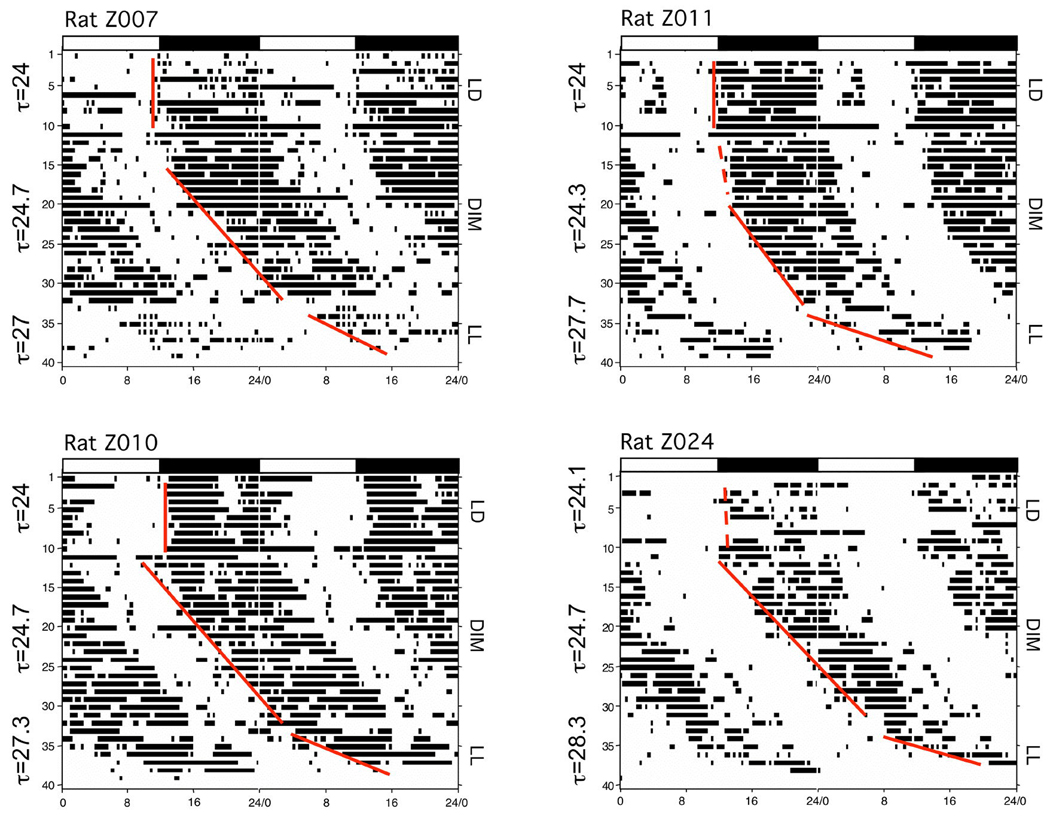

On the basis of these data, the experiment was replicated using an extended period of DIM (three weeks), allowing for a more robust estimation of TAU. In addition, at the end of the DIM period, animals were subjected to constant light (LL) conditions for one week. Figure 2 illustrates the daily cocaine self-administration profiles of 4 animals from this experiment under LD, DIM and LL conditions (data are double-plotted). As can be seen, the actograms of animals in the second experiment revealed a tight coupling of cocaine self-administration to dark period in LD as observed previously (Roberts et al. 2002). The total number of cocaine injections administered during the dark phase of the LD cycle was again significantly greater than during the light phase (17.0 ± 2.2 vs. 6.5 ± 1.3, respectively, p < 0.001). During DIM conditions, the onset of self-administration began later on consecutive days (see Figure 2). Analysis of variance revealed a main effect of lighting condition on TAU (F2,22 = 54.81, p < 0.001). TAU in LD conditions was 24.14 ±0.07h and did not differ significantly from 24h (1 sample t-test). Bonferroni comparison of ClockLab results revealed a significant increase in TAU from 24.14 ± 0.07h in LD to 24.88 ± 0.19h in DIM (p < 0.0001). Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of lighting condition on total number of cocaine injections (F2,23 = 4.26, p < 0.05). Overall, the total number of injections per day was similar between LD and DIM (25.1 ± 3.37 vs. 30.0 ± 3.16, respectively, p > 0.05). However, after transfer to bright light conditions (LL), additional delays and fragmentation of cocaine self-administration occurred. Specifically, animals displayed a further lengthening of TAU to 26.46 ± 0.23h (p < 0.001 vs. DIM and LD) and a significant reduction in total number of injections (14.3 ± 3.2 infusions/day) compared to DIM conditions (30 ± 3.16 infusions/day, p < 0.05). Unfortunately, this lower injection rate is not adequate to maintain catheter patency for extended periods. We elected to shorten the LL portion of the study rather than risk losing catheter patency, as animals that lost catheters could not be included in the final analysis.

Figure 2.

Actograms illustrating cocaine self-administration patterns in four representative rats in which catheters remained patent throughout the entire 40-day experimental period. Data are double-plotted for each animal. Each vertical black bar represents an injection taken. The alternating light:dark bars at the top of each figure represent the 12hr light (white bar):12hr dark (black bar) lighting condition prior to releasing animals into constant dim illumination (DIM, <1lux) or into constant light (LL,>1000lux). The vertical line is a best fit (based on least-squares, see Methods for details) of injection onsets during the individual lighting sessions. Individual identifying numbers are on the top left side of each actogram.

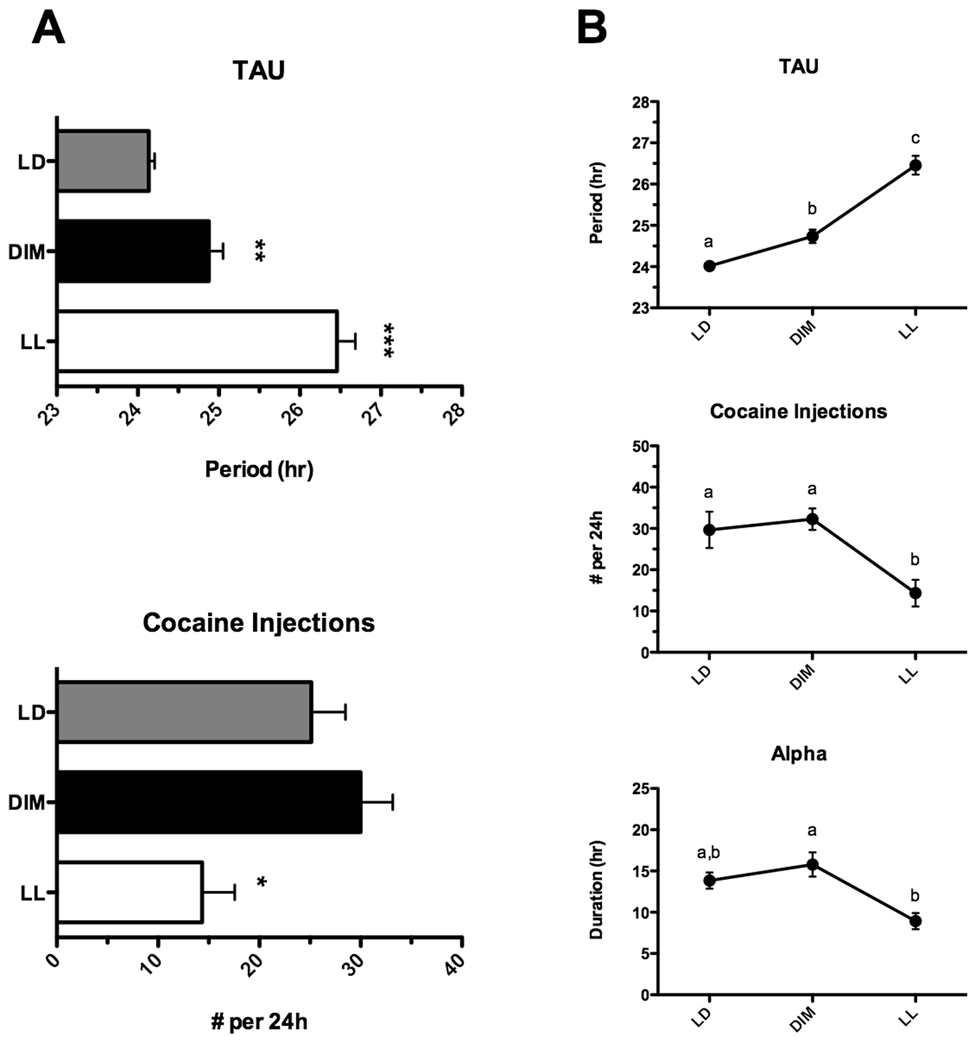

Of the ten animals used in the main experiment, five maintained patent catheters and completed the entire 40-day course of the study. The data for these five animals were analyzed separately using repeated measures ANOVA and the results are summarized in Figure 3. In addition to main effects of lighting regimen on the period length (F2,14 = 58.88, p < 0.0001) and total number of daily cocaine injections (F2,14 = 11.8, p < 0.01), we also observed a change in the duration of the cocaine self-administration bouts (alpha; F2,14 = 7.03, p < 0.05). Specifically, although alpha was similar between LD and DIM conditions (13.84 ± 0.98h vs. 15.78 ± 1.47h, p > 0.05) it was significantly shortened following the transfer to LL (8.93 ± 0.98h, p < 0.05 vs. DIM only).

Figure 3.

Summary of cocaine self-administration patterns in rats under three different lighting conditions. A. Data from all rats (n=10) illustrating mean ± SEM TAU (upper panel) and number of cocaine injections during the day (lower panel). * p<0.05 vs. LD and DIM, ** p < 0.05 vs. LD; *** p < 0.01 vs. LD. B. Data from the five rats whose catheters remained patent for the duration of the experiment illustrating the influence of lighting conditions on period length (TAU, upper panel), total number of cocaine injections (middle), and duration (in hr) of daily cocaine self-administration (alpha, lower). Difference between letters (a, b, c) designate significance (p<0.05), if data points share a letter they are not significantly different from one another.

Discussion

We have sought to establish if the daily pattern of cocaine intake using a DT3 self-administration procedure is produced via a circadian mechanism . Our initial five day DIM experiment confirms findings from others (Tornatzky and Miczek 2000) that a daily rhythm of cocaine self-administration persists in the absence of light-dark cues, suggesting an endogenous origin. Our second experiment consisting of a much longer DIM duration clearly reveals a free running period of cocaine self-administration > 24h in individual animals, supporting a circadian origin for this process. Furthermore, because the free-running TAU differed significantly from 24 h, a prerequisite for endogenous generation, the hypothesis that a circadian oscillator is responsible for the expression of daily rhythms of cocaine self-administration is supported. Lastly, the lengthening of TAU under bright illumination in LL conditions is also suggestive of an endogenous oscillator and is to be expected according to Aschoff’s rule for a nocturnal rodent (Carpenter and Grossberg 1984). The additional fragmentation and reduction in numbers of cocaine injections is reminiscent of the effects of LL on locomotor activity patterns in rats (Refinetti, 2006).

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is the most likely candidate for generating daily oscillations in cocaine self-administration and may represent the main oscillator generating this rhythm. Lesioning the SCN abolishes the diurnal variation in the levels of two important proteins in regulating dopamine transmission, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and dopamine transporter (DAT) (Sleipness et al. 2007b) as well as some aspects of cocaine induced CPP (Sleipness et al. 2007a). However, SCN lesioned animals also continue to express cocaine-induced CPP rhythms, indicating that some behavioral effects of cocaine may be under the influence of an extra-SCN oscillator (Sleipness et al. 2007a). This latter finding is reminiscent of methamphetamine treatment, which can entrain locomotor activity during a standard 12-hour LD cycle and induce a rhythm in rats made arrhythmic by SCN lesions (Honma et al. 1987; Masubuchi et al. 2000). One potential interpretation of our data is that an oscillator is driving free-running rest/activity cycles rather than motivation to self-administer. We have found that there is little correlation between wheel running activity and the likelihood of obtaining an infusion of cocaine (unpublished results). Although we cannot definitely rule out the influence of activity cycles on cocaine intake, we have shown that the highest probability of obtaining an infusion occurs five to six hours into the dark phase (Figure 1, Fitch and Roberts, 1993), as opposed to wheel running and food responding which peaks just before or with the start of the dark phase (Richter, 1922; Mistlburger, 1994). Furthermore, studies have been conducted to determine if the acute hyperlocomotion induced by methamphetamine acts as a circadian zeitgeber (Kosobud, 2007). In these studies, restricting the acute locomotor activity of the rat immediately after the injection had no effect on the resulting anticipatory wheel running that normal develops with methamphetamine infusions given every 24 h. Taken together, these data indicate that rhythms in the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine are not produced by activity cycles per se.

It has been demonstrated that constant bright light decouples the neurons within the SCN rendering their outputs arrhythmic (Ohta et al. 2005). We have used this phenomenon to determine if the circadian control of cocaine self-administration is influenced by light. In our study, constant light (1000 lux) had three profound effects on cocaine self-administration patterns: 1) rats self-administered less total cocaine, 2) constant light caused a lengthening of the endogenous period of self-administration to approximately 27 hours, and 3) the individual bout durations were significantly reduced. Under ideal circumstances, the rats would have been monitored for several weeks in LL conditions to determine if a new rhythm emerges. However, we could not accommodate an experiment of this length due to the difficulty in maintaining catheter patency with such low infusion rates for extended periods. An extended LL experiment should be conducted to conclusively prove that LL will eventually result in arrhythmic self-administration. Overall, these findings suggest that light can be used to suppress cocaine self-administration and may serve as a useful therapeutic tool. However, since sleep disturbances are common among recovering cocaine addicts, it remains to be seen whether therapeutic effects of light/dark therapy on cocaine seeking could offset the sleep disruption observed during withdrawal and abstinence.

Current theories in behavioral economics postulate that the pattern of cocaine self-administration is affected by the dose of cocaine, the difficulty in obtaining an infusion (price) and its availability. Unrestricted access to cocaine produces tightly regulated patterns of drug intake in which animals respond relatively frequently in the first few minutes of a session (“loading phase”) resulting in an elevation of blood/brain levels followed by responding that is initiated when the blood levels fall below some critical threshold (Ahmed and Koob 2005; Lynch and Carroll 2001; Panlilio et al. 2003; Tsibulsky and Norman 1999). The amount of time separating each infusion is critical for setting the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine. Cocaine binges are engendered (regardless of time-of-day) if conditions allow sufficiently high blood/brain concentrations of cocaine to be maintained (e.g. high infusion doses and/or frequent infusions). Thus, binge episodes could mask underlying circadian processes or alternatively entrain a non-SCN related rhythm, as seen with methamphetamine. The discrete trials procedure prevents animals from ‘loading-up’, limiting their ability to binge and unmasks physiological mechanisms, such as circadian drive, that influence drug intake. It must be emphasized that animals decline the opportunity to self-administer cocaine almost half the time - even at the most reinforcing dose – when access is restricted to 3 trails per hour. Understanding the mechanisms that influence the pattern of cocaine intake, particularly the tendency to decline a cocaine injection during particular times of day, could have important clinical relevance. Based on the circadian nature of cocaine self-administration, our results suggest that light (or darkness, in a diurnal organism) alone, or in combination with appropriate timing of additional treatments (i.e. phase control), could have a significant impact on the amount of cocaine self-administered.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant no. DA14030 (DCSR) and DA023202 (HTJ)

References

- Abarca C, Albrecht U, Spanagel R. Cocaine sensitization and reward are under the influence of circadian genes and rhythm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:9026–9030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142039099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Koob GF. Transition to drug addiction: a negative reinforcement model based on an allostatic decrease in reward function. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:473–490. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2180-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhisaroglu M, Kurtuncu M, Manev H, Uz T. Diurnal rhythms in quinpirole-induced locomotor behaviors and striatal D2/D3 receptor levels in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2005;80:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansah TA, Wade LH, Shockley DC. Changes in locomotor activity, core temperature, and heart rate in response to repeated cocaine administration. Physiol. Behav. 1996;60:1261–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozarth MA, Wise RA. Toxicity associated with long-term intravenous heroin and cocaine self-administration in the rat. JAMA. 1985;254:81–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower KJ, Aldrich MS, Robinson EA, Zucker RA, Greden JF. Insomnia, self-medication, and relapse to alcoholism. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:399–404. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Novy PL, Hughes JR. Marijuana withdrawal among adults seeking treatment for marijuana dependence. Addiction. 1999;94:1311–1322. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter GA, Grossberg S. A neural theory of circadian rhythms: Aschoff's rule in diurnal and nocturnal mammals. Am. J. Physiol. 1984;247:R1067–R1082. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.247.6.R1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daan S. Tonic and phasic effects of light in the entrainment of circadian rhythms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1977;290:51–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb39716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallerani M, Manfredini R, Dal Monte D, Calo G, Brunaldi V, Simonato M. Circadian differences in the individual sensitivity to opiate overdose. Crit. Care Med. 2001;29:96–101. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200101000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma K, Honma S, Hiroshige T. Activity rhythms in the circadian domain appear in suprachiasmatic nuclei lesioned rats given methamphetamine. Physiol. Behav. 1987;40:767–774. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EM, Knutson D, Haines D. Common problems in patients recovering from chemical dependency. Am. Fam. Physician. 2003;68:1971–1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosobud AEK, Gillman AG, Leffel JK, Pecoraro NC, Rebec GV, Timberlake W. Drugs of abuse can entrain circadian rhythms. ScientificWorldJournal. 2008;7 S2:203–212. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Carroll ME. Regulation of drug intake. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2001;9:131–143. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyness WH, Friedle NM, Moore KE. Destruction of dopaminergic nerve terminals in nucleus accumbens: effect on d-amphetamine self-administration. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1979;11:553–556. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(79)90040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredini R, Gallerani M, Calo G, Pasin M, Govoni M, Fersini C. Emergency admissions of opioid drug abusers for overdose: a chronobiological study of enhanced risk. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1994;24:615–618. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masubuchi S, Honma S, Abe H, Ishizaki K, Namihira M, Ikeda M, Honma K. Clock genes outside the suprachiasmatic nucleus involved in manifestation of locomotor activity rhythm in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:4206–4214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung CA, Sidiropoulou K, Vitaterna M, Takahashi JS, White FJ, Cooper DC, Nestler EJ. Regulation of dopaminergic transmission and cocaine reward by the Clock gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2005;102:9377–9381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503584102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistlberger RE. Circadian food-anticipatory activity: Formal models and physiological mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1994;18:171–195. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RW. Circadian and circannual rhythms of emergency room drug-overdose admissions. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1987;227B:451–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai M, Uchimura N, Hirano T, Ohshima H, Ohshima M, Nakamura J. Circadian rhythms of hormone concentrations in alcohol withdrawal. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1998;52:238–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta H, Yamazaki S, McMahon DG. Constant light desynchronizes mammalian clock neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:267–269. doi: 10.1038/nn1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace-Schott EF, Stickgold R, Muzur A, Wigren PE, Ward AS, Hart CL, Clarke D, Morgan A, Hobson JA. Sleep quality deteriorates over a binge--abstinence cycle in chronic smoked cocaine users. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:873–883. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2088-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Katz JL, Pickens RW, Schindler CW. Variability of drug self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;167:9–19. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittendrigh CS. Circadian rhythms and the circadian organization of living systems. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1960;25:159–184. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1960.025.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portaluppi F, Touitou Y, Smolensky MH. Ethical and methodological standards for laboratory and medical biological rhythm research. Chronobiol. Int. 2008;25:999–1016. doi: 10.1080/07420520802544530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond RC, Warren M, Morris RW, Leikin JB. Periodicity of presentations of drugs of abuse and overdose in an emergency department. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1992;30:467–478. doi: 10.3109/15563659209021561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refinetti R. Circadian physiology. 2nd edn. Boca Raton: CRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Richter CP. A behavioristic study of the activity of the rat. Comp. Psychol. Monogr. 1922;1:1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Andrews MM. Baclofen suppression of cocaine self-administration: demonstration using a discrete trials procedure. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;131:271–277. doi: 10.1007/s002130050293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Brebner K, Vincler M, Lynch WJ. Patterns of cocaine self-administration in rats produced by various access conditions under a discrete trials procedure. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67:291–299. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Corcoran ME, Fibiger HC. On the role of ascending catecholaminergic systems in intravenous self-administration of cocaine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1977;6:615–620. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(77)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Morgan D, Liu Y. How to make a rat addicted to cocaine. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;31:1614–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roybal K, Theobold D, Graham A, DiNieri JA, Russo SJ, Krishnan V, Chakravarty S, Peevey J, Oehrlein N, Birnbaum S, Vitaterna MH, Orsulak P, Takahashi JS, Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA, Jr, McClung CA. Mania-like behavior induced by disruption of CLOCK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:6406–6411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleipness EP, Sorg BA, Jansen HT. Contribution of the suprachiasmatic nucleus to day:night variation in cocaine-seeking behavior. Physiol. Behav. 2007a;91:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleipness EP, Sorg BA, Jansen HT. Diurnal differences in dopamine transporter and tyrosine hydroxylase levels in rat brain: dependence on the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain. Res. 2007b;1129:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolove PG, Bushell WN. The chi square periodogram: its utility for analysis of circadian rhythms. J. Theor. Biol. 1978;72:131–160. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(78)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Rosenwasser AM, Schumann G, Sarkar DK. Alcohol consumption and the body's biological clock. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29:1550–1557. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000175074.70807.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi JS, Turek FW, Moore RY. Circadian Rhythms. In: Adler NT, editor. Handbook of Behavioral Neurobiology. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Teplin D, Raz B, Daiter J, Varenbut M, Tyrrell M. Screening for substance use patterns among patients referred for a variety of sleep complaints. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:111–120. doi: 10.1080/00952990500328695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornatzky W, Miczek KA. Repeated limited access to i.v. cocaine self-administration: conditioned autonomic rhythmicity illustrating "predictive homeostasis". Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;145:144–152. doi: 10.1007/s002130051043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornatzky W, Miczek KA. Cocaine self-administration "binges": transition from behavioral and autonomic regulation toward homeostatic dysregulation in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;148:289–298. doi: 10.1007/s002130050053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff AM, Storr CL. Work schedule characteristics and substance use in nurses. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1998;34:266–271. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199809)34:3<266::aid-ajim9>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsibulsky VL, Norman AB. Satiety threshold: a quantitative model of maintained cocaine self-administration. Brain Res. 1999;839:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasielewski JA, Holloway FA. Alcohol's interactions with circadian rhythms. A focus on body temperature. Alcohol Res. Health. 2001;25:94–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziedonis DM, Smelson D, Rosenthal RN, Batki SL, Green AI, Henry RJ, Montoya I, Parks J, Weiss RD. Improving the care of individuals with schizophrenia and substance use disorders: consensus recommendations. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2005;11:315–339. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200509000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]