Abstract

Recent research has indicated that developmental changes in the personality traits of neuroticism and impulsivity correlate with changes in problem drinking during emerging and young adulthood. However, it remains unclear what potential mechanisms, or mediators, could account for these associations. Drinking motives, particularly drinking to regulate negative affect (drinking to cope) and to get “high” or “drunk” (drinking for enhancement) have been posited to mediate the relationship between personality and drinking problems. Recent work indicates changes in drinking motives parallel changes in alcohol involvement from adolescence to young adulthood. The current study examined changes in drinking motives (i.e., coping and enhancement) as potential mediators of the relation between changes in personality (impulsivity and neuroticism) with changes in alcohol problems in emerging and young adulthood. Analyses were based on data collected from a cohort of college students (N=489) at varying risk for AUDs from ages 18–35. Parallel process latent growth modeling indicated that change in coping (but not enhancement) motives specifically mediated the relation between changes in neuroticism and alcohol problems as well as the relation between changes in impulsivity and alcohol problems. Findings suggest that change in coping motives is an important mechanism in the relation between personality change and the “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement.

Keywords: personality change, drinking motives, alcohol use disorders, maturing out, prospective study

During emerging and young adulthood, normative developmental changes in both problematic alcohol involvement and personality traits occur. Perhaps the most salient aspect of the epidemiology of heavy use, alcohol problems, and alcohol use disorders (AUDS) in North America (at least among individuals of European descent) is the peak hazard and prevalence in emerging adulthood and the rapid decrease in both onset and prevalence that occurs in the latter part of the third decade of life (e.g., Bachman et al., 2002; Fillmore, 1988; Grant et al., 2004; Jessor, Donovan, & Costa, 1991; Yamaguchi & Kandel, 1985; see O’Malley, 2004–2005). The dramatic relation between age and AUD prevalence has led to the suggestion that AUDs should be considered developmental disorders in the sense that their appearance and resolution (so-called “maturing out”; Winick, 1962) appear tightly coupled to developmental transitions into adult roles (e.g., wage earner, spouse/partner, parent) considered to be incompatible with a heavy drinking lifestyle (Yamaguchi & Kandel, 1985; see Sher & Gotham, 1999).

Recent research has also documented both mean-level (i.e., normative) and individual differences (i.e., interindividual differences in intraindividual variation) in change in specific personality traits over the course of the life span, especially during emerging and young adulthood (e.g., Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005; McCrae et al., 1999; Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006; Robins, Fraley, Roberts, & Trzesniewski, 2001; for a review see Roberts & Mroczek, 2008).Though the relation between personality and alcohol involvement has been extensively documented (see Sher, Trull, Bartholow, & Vieth, 1999, for a review), only recently have individual differences in change in alcohol problems and personality been linked longitudinally. Littlefield et al. (2009) found decreases in impulsivity and neuroticism were associated with decreases in alcohol problems from ages 18–35 and that this relation held even when controlling for the influence of reported adult role statuses, such as marriage and parenthood.

Potential Mechanisms of Change: Drinking Motives

Although changes in personality are associated with changes in alcohol problems, it remains unclear what mechanisms, or mediators, could account for such correlated changes. Understanding the mechanisms of how broad personality traits such as neuroticism influence mental and physical health has been identified as “top priority for research” (Lahey, 2009). Based on the understanding that personality traits contribute to the motivation of behavior in general and thus are also expected to relate to specific alcohol related motivations, some theorists posit that motivations act as a proximal influence on substance use through which more distal influences, such as personality, are mediated (e.g., Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Cox & Klinger, 1988, 1990; Kuntsche, von Fisher, & Gmel, 2008; Stewart & Devine, 2000; see Sher et al., 1999). In a review of over 80 scientific reports regarding drinking motives of people aged 10–25, Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels (2006) concluded there was a robust positive relation between coping motives (i.e., drinking to alleviate negative emotional states) and neuroticism (Cooper et al., 2000; Loukas, Krull, Chassin, & Carle, 2000; Kuntsche et al., 2008; Stewart & Devine, 2000; Stewart, Loughlin, & Rhyno, 2001). Conversely, enhancement motives (i.e., drinking to enhance positive emotional states) have been linked to sensation-seeking (Comeau, Stewart, & Loba, 2001, Cooper et al., 1995), low inhibitory control (Colder & O’Connor, 2002) and impulsivity (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000) 1, though the robustness of these relations is unclear (see Kuntsche et al., 2006).

Further, both coping and enhancement motives exhibit robust relationships with alcohol involvement. As noted in a recent review (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels; 2005), enhancement motives appear related to heavy drinking (Carey, 1993; Chasin, Flora, & King, 2004; Cooper, Russell, Skinner, & Windle, 1992; Read, Wood, Kahler, Maddock, & Palfai, 2003; Schulenberg, Wadsworth, O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 1996) whereas coping motives appear related to alcohol-related problems as well as heaving drinking (Carpenter & Hasin, 1999; Cooper et al., 1995; Cooper, Russell, & George, 1988; Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Cronkite, & Randall, 2001; Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Cronkite, & Randall, 2003; McNally, Palfai, Levine, & Moore, 2003; Simons, Correia, & Carey, 2000; Windle & Windle, 1996; see also Cooper et al., 2008).

Changes in Motives and Problematic Alcohol Involvement

Though numerous cross-sectional and prospective studies have examined the relation of personality, drinking motives, and alcohol involvement (see above), there remains a paucity of prospective data that examine changes in these constructs and the relation of these changes across time. Though several recent studies suggest that changes in drinking motives correlate or “track” with changes in alcohol involvement (Patrick & Schulenberg, 2009; Sher, Gotham, & Watson, 2004) and predict changes in alcohol related problems (Cooper et al., 2008), the question remains of whether the ostensible personality effect on maturing out might be mediated by these corresponding changes in drinking motives.

Examination of the relation between changes in personality, drinking motives, and alcohol involvement is important for at least three reasons. First, it provides clarification of the relation between changes in specific personality constructs with changes in specific drinking motives. Prospective data examining the relation between developmental changes in personality and changes in drinking motives, though scarce, is important as it partially addresses the question of whether changes in specific personality traits are associated with changes in motives across time or if these relations are limited to specific developmental periods. Second, the relation of changes in drinking motives with changes in alcohol involvement can be further clarified, as only a limited number of studies (see above) have prospectively examined the relation of changes in drinking motives and alcohol involvement. Third, and of paramount interest, the degree to which drinking motives mediate the relation between the correlated changes in personality and alcohol problems over the life course has not been addressed. Building on the findings from Littlefield et al. (2009), correlated change between personality, drinking motives, and alcohol problems would call for a broader developmental framework in which changes in these constructs are viewed in the context of each other and life-stage specific contexts, roles, and challenges.

Current Study

Based on recent findings documenting the potential importance of both personality change and change in drinking motives on maturing out, the current paper sought to address two major questions: Are changes in personality and drinking motives related to one another? If so, does change in drinking motives mediate the relation between reductions in problem drinking and personality change?

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data were drawn from a longitudinal study on family history of alcoholism (FH) and other correlates of alcoholism (see Sher, Walitzer, Wood, & Brent, 1991, for a full description of the study). The baseline sample comprised of 489 first-year college students (46% male, mean age = 18.2) from a large Midwestern university. Based on criteria discussed below, half (51%) of the respondents were classified as FH positive (FH+). Respondents were prospectively assessed seven times over 16 years (roughly at ages 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 29, and 35) by both interview and paper-and-pencil questionnaire. Overall retention was good, with over 84% of participants retained over the first 11 years of the study, and over 78% retained through Year 16 (mean age = 34.5).

Measures

Family history of alcoholism

Criteria from the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST; Selzer, Vinokur, & van Rooijen, 1975), adapted to measure paternal and maternal drinking problems (F-SMAST and M-SMAST; Crews & Sher, 1992), and the Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria interview (FH-RDC; Endicott, Andreasen, & Spitzer, 1978), were used to diagnose paternal family history of alcoholism (FH) at baseline. A positive FH was coded if the biological father scored a 4 or more on the F-SMAST (see Sher et al., 1991, for additional details concerning F-SMAST criteria) and met FH-RDC criteria for alcoholism. If no first-degree relative received a diagnosis of alcohol, drug abuse, or antisocial personality disorders, and there was no alcohol or drug use disorder in a second-degree relative, negative FH was coded. In order to control for the potential influence of sex and FH on alcohol problems, drinking motives, and personality, Sex and FH were entered as exogenous variables in all bivariate growth models.

Problematic alcohol involvement

A sum of 27 items consisting of both negative consequences associated with drinking and symptoms related to alcohol dependence (consistent with the alcohol dependence syndrome described by Edwards & Gross, 1976) was calculated at each wave (approximately corresponding to ages 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 29, and 35). Items based on items from the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST; Selzer, 1971) as well as additional items were generated to produce a comprehensive list of negative consequences of alcohol consumption and dependence symptomatology (see Sher et al., 1991; items available upon request). Participants were asked if in the past year they had experienced alcohol-related consequences/symptoms (e.g., In the past year, have you… “Gotten in trouble at work or school because of drinking?”). Internal consistency, as measured by coefficient alpha (α), was .87 at age 18, .87 at age 19, .89 at age 20, .90 at age 21, .89 at age 25, .90 at age 29, and .90 at age 35.

Personality

A sum of ten items was used to assess impulsivity at baseline (age 18) and subsequently at ages 25, 29, and 35, respectively. Six of these items (e.g., I often follow my instincts, hunches, or intuition without thinking through all the details) were drawn from the short-form of the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (Short-TPQ; Sher, Wood, Crews, & Vandiver, 1995) and the remaining four items (e.g., I often do things on the spur of the moment) were taken from the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1968). Neuroticism was assessed from the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975) at ages 18, 25, 29, and 35. The Neuroticism scale includes characteristics such as anxiety, depression, guilt, shyness, moodiness, and emotionality. Internal consistency, as measured by coefficient alpha (α), was .79 at age 18, .81 at age 25, .75 at age 29, and .75 at age 35 for the impulsivity scale, and .85 at Age 18, .88 at Age 25, .85 at Age 29 and .88 at Age 35 for the Neuroticism scale.

Drinking motives

Coping and enhancement motives were assessed using items derived from a tension-reduction drinking motives composite developed by Sher et al. (1991; see Sher et al., 2004 for more details) with items adapted from those used by Cahalan, Cisin, and Crossley (1969). Coping included four items (e.g., “I drink to forget my worries”). Enhancement included one item (i.e., “I drink to get high”). Composites were created for coping motives using the sum of the items. Internal consistency, as measured by coefficient alpha (α), was .84 at age 18, .87 at age 19, .86 at age 20, .86 at age 21, .86 at age 25, .84 at age 29, and .86 at age 35 for the coping motives scale.

Analytic Procedure

To examine the potential mediating variables (M) of changes in drinking motives intervening in the relation between the antecedent variables (X) of changes in personality and the outcome variable (Y) of changes in alcohol problems, parallel process latent growth modeling (LGM) was utilized (Cheong, MacKinnon, & Khoo, 2003; MacKinnon, 2008). Referred to as the “state-of-the-art in the estimation of longitudinal mediation effects” (Jagers et al., 2007, p. 175), parallel process LGM expands the application of both traditional mediational analysis (e.g., Barron & Kenny, 1986) and latent growth modeling (e.g., Meredith & Tisak, 1990) by combining both approaches into one methodological framework. When the antecedent (X), mediating (M), and outcome (Y) variables are measured repeatedly over time, the growth of the X, M, and Y variables can be viewed as three distinct processes (Cheong et al., 2003; MacKinnon, 2008). The mediational process is then modeled assuming that growth in the antecedent variable relates to growth of the outcome variable indirectly through the growth in the mediator. Support for mediation is found when the trajectory of the antecedent variable significantly relates to the trajectory (i.e., slope) of the mediator, which, in turn, relates to the trajectory of the outcome (Cheong et al., 2003; MacKinnon, 2008)2. Further, to appropriately estimate confidence intervals for mediated effects, parallel process LGM also utilizes the Asymmetric Confidence Interval (ACI) method (see MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; for more details).

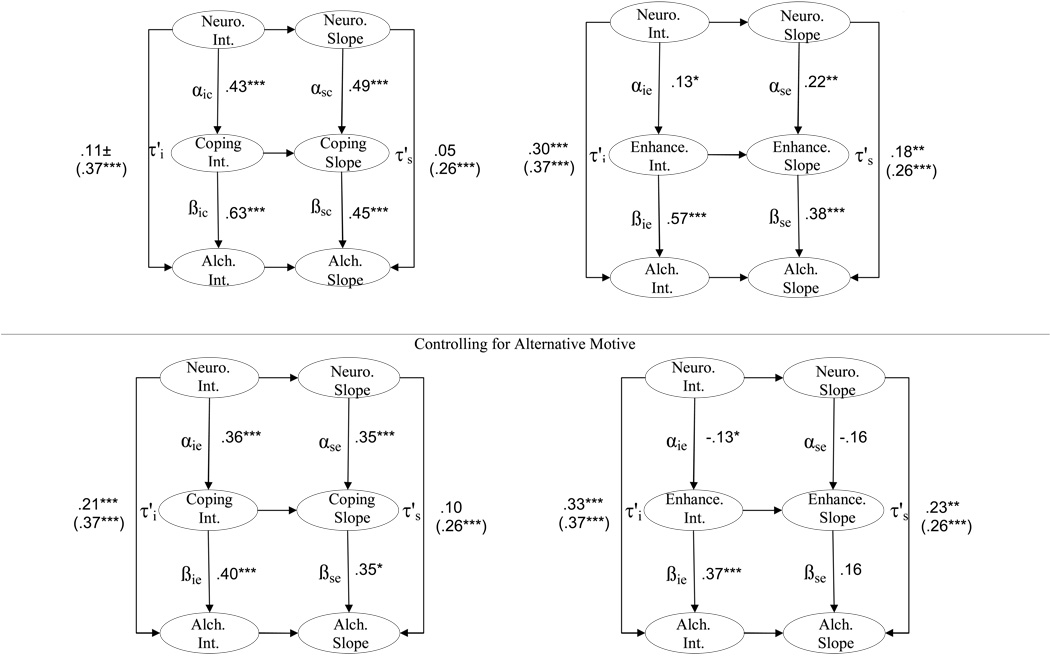

A parallel process LGM for personality, drinking motives, and alcohol problems is illustrated in Figure 1. The personality intercept and personality slope represent the LGM of the respective personality constructs (i.e., impulsivity, neuroticism). Likewise, the drinking motive intercept and slope represents the LGM of the respective drinking motives (i.e., coping, enhancement), and the alcohol problems intercept and slope represents the LGM of the alcohol problem variables. Intercept factors represent initial level (roughly age 18) associated with their respective constructs. Slope factors depicted in Figure 1 indicate change in their respective constructs from roughly age 18 to age 35. The relation of initial level (intercept) in personality is modeled as a predictor of both initial level of drinking motive and alcohol problems, and drinking motive intercept is modeled as an additional predictor of alcohol problems (though see the Limitations section below regarding alternative model specifications). Similarly, change in personality (personality slope) is modeled as a predictor of both drinking motive and alcohol problem slope, and drinking motive slope is modeled as a predictor of alcohol problem slope. Directional paths are modeled between intercepts and slopes, both within and across constructs (i.e., changes in personality, drinking motives, and alcohol problems are controlled for the initial level of these constructs3). Mediational processes concerning initial level (intercept) and change (slope) in the respective constructs of personality, drinking motives, and alcohol problems are explored within the context of this model (see Figure 1, Cheong et al., 2003 for more details). Briefly, regarding mediational hypotheses involving the intercepts, the mediated effect is determined by the extent to which initial level of personality predicts initial level of drinking motive (αi) and, in turn, the extent to which the initial level of drinking motive predicts initial levels of alcohol problems (βi) (Cheong et al., 2003). In parallel fashion (and of primary interest), mediational processes involving changes in personality, drinking motive, and alcohol problems can also be addressed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Parallel Process Latent Growth Model.

Direct Effect of Initial Level (age 18) of Personality on Initial Level of Alcohol Problems= τ'i. Indirect Effect of Initial Level of Personality on Initial Level of Alcohol Problems= αiβi. Total Effect of Initial Level of Personality on Initial Level of Alcohol Problems= τ'i + αiβi. Direct Effect of Personality Change on Change in Alcohol Problems= τ's. Indirect Effect of Personality Change on Change in Alcohol Problems= αsβs. Total Effect of Personality Change on Change in Alcohol Problems= τ's + αsβs.

Results

Latent Growth Models

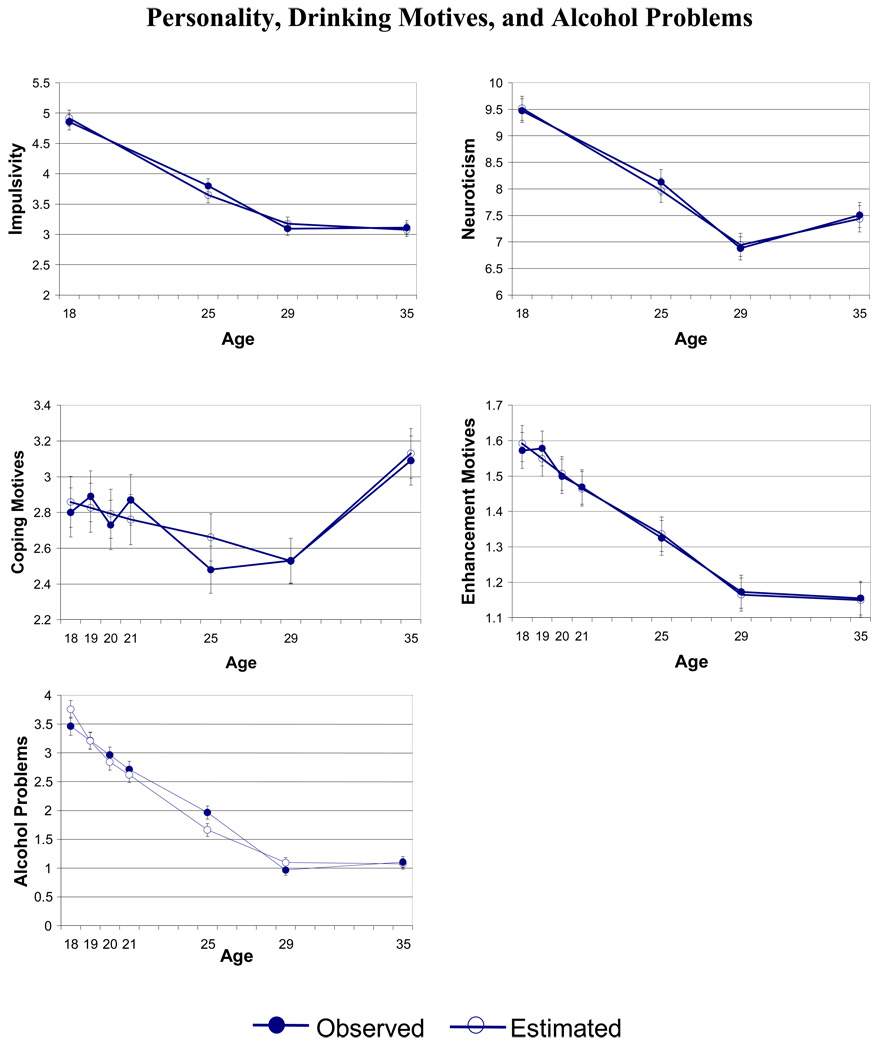

Mean-level changes in impulsivity, neuroticism, coping, enhancement, and alcohol problems are shown in Figure 2. Zero-order correlations among the drinking motives of coping and enhancement with the constructs impulsivity, neuroticism, alcohol problems, biological sex, and family history of alcoholism are presented in Table 1. Zero-order correlations among coping and enhancement motives are presented in Table 2 (zero-order correlations among the other constructs of interest can be found in Littlefield et al., 2009). Participants who reported abstaining from alcohol across all assessments (n = 6) were excluded from all analyses. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) LGMs with robust standard errors (Satorra & Bentler, 1994) were estimated with Mplus Version 5.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). Mediated (i.e., indirect) effects with 95% asymmetric confidence intervals (MacKinnon et al., 2002) were calculated using Program PRODCLIN (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). To allow for analysis of data containing missing values, all LGMs were estimated using full information maximum likelihood, which assume that data are missing at random4.

Figure 2.

Observed (FIML, N = 483) and estimated (from LGMs) mean-level changes (with standard errors) for impulsivity, neuroticism, coping motives, enhancement motives, and past-year alcohol problems.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations between coping and enhancement motives and indices of impulsivity, neuroticism, past-year alcohol problems, sex and family history of alcoholism

| Coping Motives | Enhancement Motives | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 25 | 29 | 35 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 25 | 29 | 35 |

| Impulsivity 18 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.07 a | 0.11 | 0.08 a | −0.03 a | 0.01 a | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.07 a | 0.03 a | 0.10 a |

| Impulsivity 25 | 0.08 a | 0.09 a | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.01 a | 0.08 a | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.07 a | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.08 a | 0.14 |

| Impulsivity 29 | 0.06 a | 0.01 a | 0.06 a | 0.06 a | 0.10 a | 0.09 a | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.06 a | 0.08 a | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.17 |

| Impulsivity 35 | 0.08 a | 0.09 a | 0.04 a | 0.08 a | 0.09 a | 0.12 | 0.09 a | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.07 a | 0.05 a | 0.09 a | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Neuroticism18 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.09 a | 0.09 a | 0.07 a | 0.08 a | 0.12 | 0.07 a | 0.10 a |

| Neuroticism 25 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.04 a | 0.06 a | 0.06 a | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| Neuroticism 29 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.00 a | 0.01 a | 0.00 a | 0.04 a | 0.14 | 0.06 a | 0.09 a |

| Neuroticism 35 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.32 | −0.02 a | 0.01 a | 0.01 a | 0.03 a | 0.07 a | 0.07 a | 0.11 |

| Alcohol Prob. 18 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.33 |

| Alcohol Prob. 19 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.28 |

| Alcohol Prob. 20 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.27 |

| Alcohol Prob. 21 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| Alcohol Prob. 25 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.39 |

| Alcohol Prob. 29 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| Alcohol Prob. 35 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.37 |

| Sex | −0.05 a | −0.14 | −0.13 | −0.13 | −0.08 a | −0.04 a | −0.02 a | −0.18 | −0.15 | −0.13 | −0.20 | −0.29 | −0.20 | −0.17 |

| Family History | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.10 a | 0.09 a | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.08 a | −0.02 a | 0.04 a | 0.08 a | 0.15 | 0.26 |

| Mean | 2.80 | 2.89 | 2.73 | 2.87 | 2.48 | 2.53 | 3.09 | 1.57 | 1.58 | 1.49 | 1.47 | 1.32 | 1.17 | 1.16 |

| SD | 3.02 | 3.12 | 3.03 | 3.09 | 2.90 | 2.74 | 3.02 | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 1.05 |

Note. N=483. 0 = men, 1 = women. Alchohol Prob. = alcohol problems.

p<.05 for all parameters expect those with superscript a.

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations between coping and enhancement motives

| Coping Motives | Enhancement Motives | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 25 | 29 | 35 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 25 | 29 | 35 |

| C. Motives Age 18 | ||||||||||||||

| C. Motives Age 19 | 0.63 | |||||||||||||

| C. Motives Age 20 | 0.55 | 0.60 | ||||||||||||

| C. Motives Age 21 | 0.50 | 0.58 | 0.59 | |||||||||||

| C. Motives Age 25 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.56 | ||||||||||

| C. Motives Age 29 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.61 | |||||||||

| C. Motives Age 35 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.64 | ||||||||

| E. Motives Age 18 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.22 | |||||||

| E. Motives Age 19 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.69 | ||||||

| E. Motives Age 20 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.64 | 0.67 | |||||

| E. Motives Age 21 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.65 | ||||

| E. Motives Age 25 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.619 | |||

| E. Motives Age 29 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.481 | 0.57 | ||

| E. Motives Age 35 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.395 | 0.52 | 0.64 | |

Note. N=483. 0 = men, 1 = women. C. Motives = coping motives. E. Motives = enhancement motives. p<.05 for all parameters.

Univariate Growth Models

Relations between personality, drinking motives, and alcohol problems were examined using the methodology outlined by Cheong et al. (2003). Univariate growth models for the initial level (intercept) and changes across time (slope) of personality (impulsivity and neuroticism), drinking motives (coping and enhancement), and alcohol problems were first estimated. Based on tests of model fit and patterns of mean-level change, a random intercept and a non-linear slope (i.e., the slope loading for the first six waves of assessment were set to be linear [0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 11] and the last assessment was freely estimated) were estimated for each construct of interest. These models provided adequate fit to the data (i.e., CFI > .90; RMSEA & SRMR < .08; Kline, 2005). Slope parameters indicated that, overall, individuals decreased in impulsivity, neuroticism, enhancement (but not coping6) motives, and alcohol problems from ages 18–35 (see Figure 2). Additionally, the respective slope parameters for all constructs exhibited significant variance (p<.001), suggesting that individual differences in change occur in all constructs across time.

Next, the extent of correlated change in personality, drinking motives, and alcohol problems was examined via a similar series of parallel process latent growth models. All parallel process LGMs consisted of an intercept and a non-linear slope (i.e., the slope loading for the last assessment was freely estimated) for each construct of interest (see Cheong et al., 2003 for a discussion involving non-linear parallel process LGM). In order to enhance interpretability, the freely estimated slope loadings (at the final measurement occasion) for the respective personality, drinking motives, and alcohol involvement constructs in each parallel process LGM were constrained to be equal across processes7. Further, FH and Sex were included as exogenous variables (i.e., exerting a direct influence on all study constructs’ intercept and slope) in all models.

Measurement Model

An overall measurement model (i.e., a model in which every latent variable is correlated) including growth processes for personality (impulsivity and neuroticism), drinking motives (coping and enhancement), and alcohol problems was then fit (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). This model provided adequate fit to the data (χ2 [407, n = 483] = 915.517, p<.001; CFI = .91; RMSEA =.05; SRMR = .04). Respective correlations among the intercepts and slopes of all personality, motives, and alcohol involvement constructs are presented in Table 3. Briefly, the respective intercept and slopes of all constructs of interest were significantly correlated (at p<.05) with the exception of impulsivity and neuroticism intercept and impulsivity and neuroticism slope, supporting the further examination of the mediational processes involving personality, drinking motives, and alcohol problems.

Table 3.

Correlations between the respective intercepts and the respective slopes of impulsivity, neuroticism, coping motives, enhancement motives, and alcohol problems

| Intercept correlations for impulsivity, neuroticism, coping motives, enhancement motives, and alcohol problems | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | I-intercept (1) | N-intercept (2) | C-intercept (3) | E-intercept (4) |

| I-intercept (1) | ||||

| N-intercept (2) | .13 | |||

| C-intercept (3) | .24*** | .42*** | ||

| E-intercept (4) | .24*** | .13* | .56*** | |

| AP-intercept (5) | .45*** | .38*** | .69*** | .63*** |

| Slope correlations for impulsivity, neuroticism, coping motives, enhancement motives, and alcohol problems | ||||

| Construct | I-slope (1) | N-slope (2) | C-slope (3) | E-slope (4) |

| I-slope (1) | ||||

| N-slope (2) | .14 | |||

| C-slope (3) | .53*** | .51*** | ||

| E-slope (4) | .33** | .23** | .75*** | |

| AP-slope (5) | .42*** | .40*** | .72*** | .61** |

Note. N=483. I=impulsivity. N=neuroticism. C=coping. E=enhancement. AP=alcohol problems. All variables are controlled for family history of alcoholism and sex.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Personality: Relation with Alcohol Problems and Drinking Motives

A series of parallel process LGMs were then estimated to examine the potential mediating role of drinking motives in the relation between personality and alcohol problems. All models discussed below exhibited adequate fit to the data (i.e., CFI > .90; RMSEA & SRMR < .08; Kline, 2005). First, to examine the relation of changes in personality on changes in alcohol problems, the respective LGMs of neuroticism and impulsivity were combined with the LGM of alcohol problems in two separate parallel process models. Notably, the current models specify directional paths between the intercept and slopes, both within and across constructs (i.e., changes in alcohol problems and personality are controlled for the initial level of these constructs). Further, the relation of initial level (intercept) as well as changes (slope) in personality and alcohol problems was modeled as directional; that is, the intercept of alcohol problems was regressed onto the respective intercepts of impulsivity and neuroticism and the slope of alcohol problems is regressed onto the respective slopes (and intercepts) of impulsivity and neuroticism (see Analytic Procedure above)8. Results from these analyses suggested that the respective relation between personality (neuroticism, impulsivity) intercept and slope and alcohol problems intercept and slope was significant, positive, and at a magnitude consistent with medium effect sizes (Cohen, 1988; see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Parallel Process Latent Growth Models of Neuroticism, Drinking Motives, and Alcohol Problems.

Neuro. = neuroticism. Enhance = Enhancement. Alch. = Alcohol Problems. Direct Effect of Initial Level (age 18) of Neuroticism on Initial Level of Alcohol Problems= τ'i. Direct Effect of Neuroticism Change on Change in Alcohol Problems= τ's. All within-construct and across-construct paths were estimated but not presented. Total effects between neuroticism and alcohol problems are displayed in parentheses. All variables were controlled for family history of alcoholism and sex. The results presented in the bottom panel included these additional specifications: coping intercept was controlled for enhancement intercept. Coping slope was controlled for enhancement intercept and slope. Enhancement intercept was controlled for coping intercept. Enhancement slope was controlled for coping intercept and slope. ±p<.10, *p<.05, **p<.01,***p<.001.

Second, in order to examine the relation of changes in personality on changes in drinking motives, the respective LGMs of neuroticism and impulsivity were combined with the respective LGMs of coping and enhancement motives, resulting in four separate bivariate growth models (i.e., neuroticism with coping, neuroticism with enhancement, impulsivity with coping, and impulsivity with enhancement) modeled in parallel fashion to the previously discussed personality and alcohol problems bivariate growth models.

Results of the respective parallel process growth models for neuroticism and impulsivity with alcohol problems and drinking motives are presented in Table 4. The intercept and slope of neuroticism positively predicted coping motives intercept and slope, respectively. That is, individuals high in initial levels of neuroticism tended to also be higher in baseline coping motives; individuals who decreased in neuroticism were also more likely to decrease in coping motives across time. Similarly, the intercept and slope of neuroticism also positively predicted enhancement motives intercept and slope, respectively, though the magnitude of the effects were larger for the relation between the neuroticism and coping motives growth parameters (see Table 4). Impulsivity intercept and slope positively predicted both drinking motives intercept and slope, respectively.

Table 4.

Standardized coefficients for respective parallel process latent growth models of neuroticism and impulsivity with alcohol problems, coping motives, and enhancement motives

| Neuroticism and alcohol problems parallel process model | |

| β | |

| Neuroticism Intercept → Alcohol Problems Intercept | .37*** |

| Neuroticism Slope → Alcohol Problems Slope | .26*** |

| Neuroticism and coping motives parallel process model | |

| Neuroticism Intercept → Coping Motives Intercept | .43*** |

| Neuroticism Slope → Coping Motives Slope | .48*** |

| Neuroticism and enhancement motives parallel process model | |

| Neuroticism Intercept → Enhancement Motives Intercept | .13* |

| Neuroticism Slope → Enhancement Motives Slope | .22** |

| Impulsivity and alcohol problems parallel process model | |

| Impulsivity Intercept → Alcohol Problems Intercept | .44*** |

| Impulsivity Slope → Alcohol Problems Slope | .21** |

| Impulsivity and coping motives parallel process model | |

| Impulsivity Intercept → Coping Motives Intercept | .24** |

| Impulsivity Slope → Coping Motives Slope | .40** |

| Impulsivity and enhancement motives parallel process model | |

| Impulsivity Intercept → Enhancement Motives Intercept | .24** |

| Impulsivity Slope → Enhancement Motives Slope | .22** |

Note. N=483. All variables are controlled for family history of alcoholism and sex.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Drinking Motives and Alcohol Problems

Third, consistent with model specifications regarding relations among personality, alcohol problems, and drinking motives, the relations between each drinking motive (coping and enhancement) and alcohol problems were examined. Initial levels of coping motives predicted initial levels of alcohol problems (β = .68, p<.001); changes in coping motives also predicted changes in alcohol problems (β = .47, p<.001). Similarly, initial level as well as changes in enhancement were respectively related to the intercept (β = .61, p<.001) and slope (β = .42, p<.001) of alcohol problems.

Mediational Modeling of Personality, Motives, and Alcohol Problems

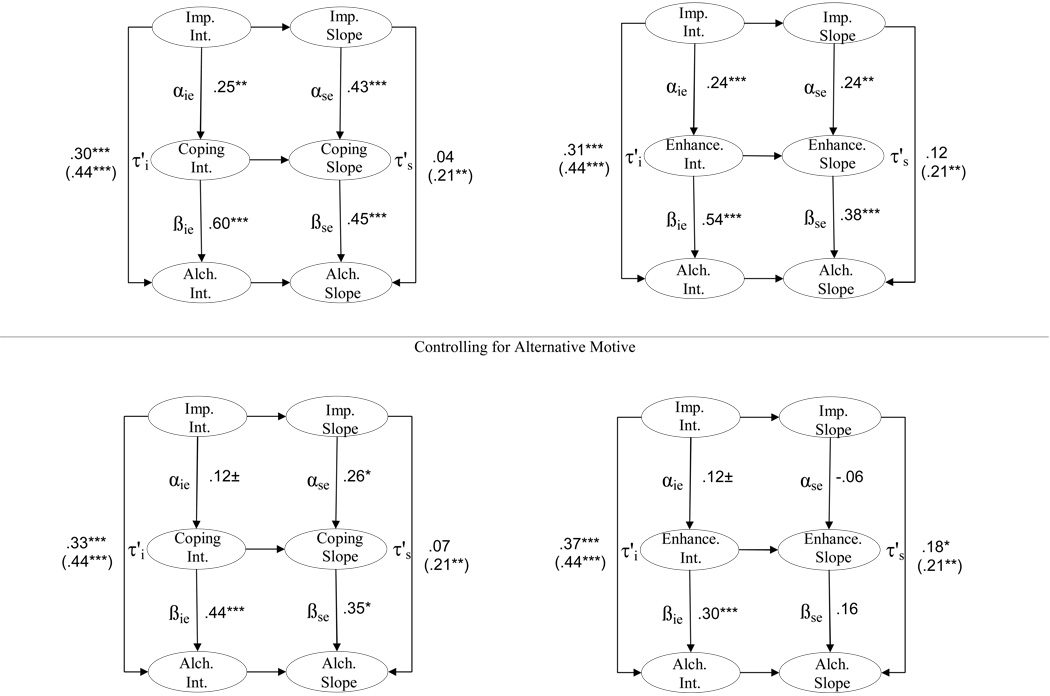

In order to assess the mediating role of motivational changes in the relation between personality change and change in alcohol problems, two parallel process LGMs were estimated for each personality construct separately (i.e., neuroticism and impulsivity): coping motives as a mediator and enhancement motives as a mediator. This resulted in four total parallel process LGMs (2 personality constructs × 2 model specifications) illustrated in top panel of Figures 4 (for neuroticism) and 5 (for impulsivity).

Figure 4. Parallel Process Latent Growth Models of Impulsivity, Drinking Motives, and Alcohol Problems.

Imp. = impulsivity. Enhance = Enhancement. Alch. = Alcohol Problems. Direct Effect of Initial Level (age 18) of Impulsivity on Initial Level of Alcohol Problems= τ'i. Direct Effect of Impulsivity Change on Change in Alcohol Problems= τ's. All within-construct and across-construct paths were estimated but not presented. Total effects between impulsivity and alcohol problems are displayed in parentheses. All variables were controlled for family history of alcoholism and sex. The results presented in the bottom panel included these additional specifications: coping intercept was controlled for enhancement intercept. Coping slope was controlled for enhancement intercept and slope. Enhancement intercept was controlled for coping intercept. Enhancement slope was controlled for coping intercept and slope. ±p<.10, *p<.05, **p<.01,***p<.001.

Neuroticisim

Coping motives intercept partially mediated the relation between initial levels of neuroticism and alcohol problems (see top panel of Figure 3). Further, the mediated effect (i.e., the indirect effect (IE) of neuroticism intercept on alcohol problems intercept through coping intercept) tested by the asymmetric CI method was also significant (IE = .269 95% CI = .188, .357). Of principal interest, changes in coping motives partially mediated the effects of changes in neuroticism on changes in alcohol problems (IE = .222, 95% CI = .116, .351).

The intercept of enhancement motives partially mediated the relation between initial levels of neuroticism and alcohol problems (see top panel of Figure 3; IE= .076, 95% CI = .012, .142). Similarly, enhancement slope partially mediated the relation between changes in neuroticism on changes in alcohol problems (IE = .083, 95% CI = .022, .153).

Impulsivity

Coping motives intercept partially mediated the relation between initial levels of impulsivity and alcohol problems (see top panel of Figure 4; IE= .148, 95% CI = .061, .240). Changes in coping motives partially mediated the effects of changes in impulsivity on changes in alcohol problems (IE = .194, 95% CI = .072, .352).

Regarding enhancement motives, the intercept of enhancement motives partially mediated the relation between initial levels of impulsivity and alcohol problems (IE= .131, 95% CI = .057, .210). Changes in enhancement motives partially mediated the effects of changes in impulsivity on changes in alcohol problems (IE = .089, 95% CI = .024, .165).

Specific Mediation of Coping and Enhancement Motives

The potential of each drinking motive as a specific mediator of the relation between personality and alcohol problems was then examined in four analyses corresponding to the parallel process LGMs discussed above. In order to assess specific mediation, coping motive intercept was controlled for the intercept of enhancement motive and coping motive slope was controlled for the intercept and slope of enhancement motive; in a parallel fashion, enhancement motive intercept was controlled for the intercept of coping motive and enhancement motive slope was controlled for the intercept and slope of coping motives.

Results of these analyses are displayed in bottom panel of Figures 4 (for neuroticism) and 5 (for impulsivity). Both coping motive intercept (IE= .145, 95% CI = .086, .215) and coping motive slope (IE = .120, 95% CI = .007, .269) remained significant mediators of the relation between neuroticism and alcohol problems when controlling (as previously outlined) for enhancement growth factors. Conversely, when controlling for coping motive intercept, the relation between neuroticism intercept and enhancement intercept became negative (β = −.13, p<.05). Further, the direct relation between neuroticism and alcohol problems remained statistically significant and of similar magnitude (β = .33, p<.01) compared to the total effect between these two constructs (β = .37, p<.01; see bottom panel of Figure 3), though the results from the ACI suggested that enhancement motives remained a significant mediator between neuroticism intercept and alcohol problem intercept (IE = −.048, 95% CI = −.097, −.004). Controlling for coping intercept and slope, the relation between changes in neuroticism with changes in enhancement also became negative though statistically nonsignificant (β = −.16, p=.19) and enhancement motives failed to remain a significant mediator between neuroticism slope and alcohol problem slope (IE = −.026, 95% CI = −.097, .016).

Regarding impulsivity, coping motive intercept (IE= .051, 95% CI = −.005, .111) failed to remain a significant mediator between the respective intercepts of impulsivity and alcohol problems when controlling for enhancement. However, coping motive slope remained a statistically significant mediator of the relation between the respective slopes of impulsivity and alcohol problems (IE= .091, 95% CI = .002, .230); further, changes in impulsivity significantly predicted changes in coping motives and the direct effect of changes in impulsivity on changes in alcohol problems was reduced in this model (see bottom panel of Figure 4). Further, controlling for coping motives slope, the respective relation between impulsivity intercept and slope with enhancement intercept and slope became statistically nonsignificant (see Figure 4); consequently, enhancement motives intercept (IE = .035, 95% CI = −.005, .081) and slope (IE = −.009, 95% CI = −.057, .028) failed to remain significant respective mediators between impulsivity and alcohol problems.

Discussion

Significant developmental changes in both problematic alcohol involvement and personality traits occur throughout emerging and young adulthood with alcohol problems tending to decline and personality moving in the direction of greater emotional stability and self control. As shown here and in earlier analysis of this data (Littlefield et al., 2009), individual variation in these developmental changes are correlated, suggesting that the well documented phenomenon of “maturing out” appears to be related to attaining greater psychological maturity. Expanding on these previous findings, the current set of analyses demonstrate that changes in motives appear to be a highly plausible mechanism linking these two growth processes and suggest that changes in personality, drinking motives, and problematic alcohol involvement should be considered from a developmental framework in which changes in these constructs are functionally linked.

Changes in Neuroticism, Drinking Motives, and Alcohol Problems

Results from the current paper extend and clarify the extant work involving personality, drinking motives, and alcohol involvement in several respects. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relation of changes in personality with changes in drinking motives during emerging and young adulthood. The findings are consistent with affect regulation models (see Sher et al., 1999; Sher & Grekin, 2007) that posit individuals with the tendency to experience negative emotional states (i.e., neuroticism) may be motivated to engage in alcohol use in order to alleviate negative emotional states (i.e., drinking to cope; Cooper et al., 1995). Importantly, the findings highlights the importance of affection regulation in the phenomenon of maturing out, a process that had hitherto been primarily conceptualized as a more environmentally driven process (i.e., role incompatibility; Yamaguchi & Kandel, 1985).

Consistent with previous cross-sectional examinations of the relation between neuroticism and enhancement motives that suggest low neuroticism is a significant independent predictor of residual enhancement motives scores (e.g., Stewart et al., 2001), analyses that included both drinking motives indicated that initial levels of enhancement motives were negatively related to baseline levels of neuroticism, such that individuals high in neuroticism at approximately age 18 were lower in enhancement motives when coping motives were controlled. A similar pattern emerged for changes in these constructs though this relation was not statistically significant. Additionally, the relation between changes in neuroticism and changes in alcohol problems was only significantly mediated by changes in drinking to cope. Therefore, it appears that that coping (but not enhancement) motives specifically perform as statistical mediators of the relation between changes in neuroticism and alcohol problems.

Changes in Impulsivity, Drinking Motives, and Alcohol Problems

There was also evidence that changes in impulsivity corresponded to changes in coping motives across time, such that individuals that decline in impulsivity across time were more likely to make reductions in drinking to cope. These findings may reflect poorer coping skills among individuals who are consistently high in impulsivity. As Cooper et al. (2000) note, individuals high in impulsivity are prone to engage in risky behaviors that maximize immediate gains despite distal negative outcomes. Thus, individuals who evince reductions in impulsivity across time may also be more likely to engage in more adaptive coping mechanisms and, accordingly, be less likely to engage in drinking to cope as means to manage negative emotional states. Conversely, individuals who fail to demonstrate reductions/shallower declines in impulsivity may be more apt to continue to utilize coping strategies that maximize immediate gains despite the potential of later negative consequences, such as drinking to cope.

Changes in impulsivity failed to remain a significant predictor of changes in enhancement in analyses that accounted for coping motives. These results parallel previous research that has documented a tenuous relation between impulsivity and enhancement motives (e.g., Cooper et al., 2000). Consistent with the findings concerning neuroticism, there is evidence that individuals that decline in impulsivity decrease in coping (but not enhancement) motives, and in turn make reductions in alcohol problems (and vice versa).

Clinical Implications

The current study provides support for the idea that understanding “maturing out” or “natural recovery” can provide potential targets for clinical intervention (e.g., Sobell, Sobell, & Toneatto, 1992; Watson & Sher, 1998). Littlefield et al. (2009) speculatively noted several possible interventions targeted at reducing personality traits related to drinking, such as career counseling as a possible intervention to decrease neuroticism (Scollon & Diener, 2006) as well as exercise regimes and cognitive skills programs (Baumeister, Gailliot, DeWall, & Oaten, 2006) to facilitate changes in impulsivity by increasing self-regulation. While most cognitive and behavioral treatment approaches have targeted variables proximal to drinking and drinking itself, the focus on changing distal factors (long a goal of traditional psychotherapies such as psychodynamic approaches) must be viewed as a potentially valuable strategy in light of increasing data highlighting the malleability of personality.

Another implication is to use personality (and associated motives) as a matching variable for different treatment approaches. For example, Conrod et al. (2000) developed treatments tailored to individuals with different substance use motivations associated with different personality dimensions. Since current results suggest that reductions in coping motives predict reductions in problem drinking, treatments targeting coping skills (see Marlatt & Witkiewitz, 2009; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004) or take into account individual differences in personality and drinking motives, such as the work by Conrod and colleagues (e.g., Conrod et al., 2000; Conrod et al., 2008; see Sher & Martinez, 2009), may result in substantial, beneficial, and durable reductions in alcohol problems. Further, empirical evidence suggests that approaches tailored to addressing individual differences in drinking motives that are related to personality can delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking (Conrod, Castellanos, & Mackie, 2008).

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study should be noted. The sample from the current study was initially drawn from first-time college freshman entering a large university, which limits generalizability of findings to noncollegiate populations. In addition, the sample is predominately White (93%) and thus caution should be taken in generalizing these findings to other racial/ethnic groups who show different developmental trends (and patterns of maturing out) than is found in the majority culture (e.g., Cooper et al., 2008). Also, the sample size was not large enough to allow separate LGMs for family history positive/negative individuals or for men/women to be conducted and determine whether the oversampling of FH positive participants and the exclusion of indeterminate FH individuals might have influenced findings in unknown ways. Despite these limitations, it should be briefly noted that findings presented here regarding the correlated change between drinking motives and alcohol problems appear to be consistent with preliminary findings in nationally representative data regarding correlated change among reasons to drink and risky drinking (Patrick & Schulenberg, 2009).

Additionally, our personality assessment failed to resolve the multidimensionality of traits such as neuroticism (Costa & McCrae, 1992) and impulsivity (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001) and so more specific relations than those that are found here may exist. Notably, when correlated (in a separate sample) with the recently identified five facets of impulsivity (see Cyders et al., 2007; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001), our impulsivity measure correlated strongest (r=.56, p<.0001) with the (lack of) premediation subscale.

Perhaps the major limitation of the current study was that “enhancement” motivation was assessed by one item (i.e., I drink to get high). This shortcoming is a result of the longitudinal nature of the current data set. Baseline assessment (in 1987) occurred before the advent of well established, multidimensional measures of drinking motives (e.g., DMQ-R; Cooper, 1994). Despite this limitation, there are a number of findings that support the validity of the one item measure. First, the item “I drink to get high” correlates highly (r=.84) with the full measure of enhancement motives from the DMQ-R (which was available at the last two waves of the current study). Second, evidence suggests that “I drink to get high” may be the most important element concerning the relation of enhancement scales with drinking outcomes( Kuntsche et al, (2005)., Third, findings from the current study using the one-item measure of enhancement parallel previous findings involving full measures of enhancement: When coping motives were accounted for, enhancement: 1) negatively correlated with neuroticism (e.g., Stewart et al., 2001), 2) failed to mediate the relation between neuroticism and alcohol involvement (e.g., Cooper et al., 2000), 3) failed to be significantly related to impulsivity (e.g., Cooper et al., 2000), 4) failed to significantly predict alcohol problems (e.g., Cooper et al., 1995). Fourth, a series of autoregressive models (similar to those employed by Cooper et al., 2008) utilizing the full measure of enhancement from the DMQ available at ages 29 and 35 provided results consistent with several conclusions drawn in the paper. Though these findings bolster the support for the validity of the one-item measure of enhancement, our conclusions would be strengthened by replicating the current findings with a more comprehensive enhancement measure.

Finally, the current paper examined changes in personality as predictors of changes in drinking motives, and in turn changes in drinking motives as predictors of changes in alcohol problems. Though the explicit modeling of longitudinal growth of personality, drinking motives, and alcohol problems that utilize multiple measurements to estimate long-term change results in a better test of mediational relations than cross-sectional data, causal conclusions regarding the relation between the growth factors of personality, drinking motives, and alcohol problems must be based on strong theoretical ground (Cheong et al., 2003). Absent of strong theory, the relation between the growth rate factors of personality, drinking motives, and alcohol problems may only be interpreted as correlational, because these variables were measured simultaneously on each occasion and levels on these variables were obviously not randomly assigned (Cheong et al., 2003). It should also be stressed that the analyses proposed here, though consonant with extant theory and research on the relations between personality, motives, and alcohol involvement, by no means exhaust the plausible theoretical and analytic models which could be applied to these data. The causal structure assumed by the mediational models proposed may also be fit equivalently by models which make no such attributions of causal influence between the psychological constructs of personality, motive, and alcohol problems (see Tomarken & Waller, 2003). Despite these interpretational limitations, the current findings are bolstered by a rich theoretical and empirical literature documenting the relations between personality, drinking motives, and alcohol outcomes (see Kuntsche et al., 2006 for an extensive review).

Conclusions

Current findings suggest that reductions in neuroticism and impulsivity correspond to reductions in coping and enhancement motives between the ages of 18 to 35; however, the relation between changes in these personality constructs and enhancement motives became statistically nonsignificant when coping motives were taken into account. There was also evidence that changes in coping and enhancement motives mediated the relation between personality change and problematic alcohol problems, though enhancement motives failed to remain a significant mediator when controlling for coping motives. These results support a developmental framework in which changes in these constructs are viewed in the context of each other. Additionally, results from the current study provide preliminary evidence that change in coping motives is an important mechanism in the relation between the “maturing out” of alcohol problems and personality change.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants T32 AA13526, R01 AA13987, R37 AA07231 and KO5 AA017242 to Kenneth J. Sher and P50 AA11998 to Andrew Heath. We gratefully acknowledge Julia A. Martinez and Amelia E. Talley for their insightful comments on a previous version of this article. Also, we thank the staff of the Alcohol, Health, and Behavior and IMPACTS projects for their data collection and management.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/abn.

Enhancement motives have also been associated with extraversion (e.g., Kuntsche, von Fisher, Gmel, 2008; see Kuntsche et al., 2006). However, results from Littlefield et al. (2009) suggested that changes in extraversion did not track with changes in alcohol problems across time, thus precluding analyses examining changes in enhancement motives as a mediator between changes in extraversion and alcohol problems.

Causality is not necessarily established in these models (i.e., these models are still correlational in nature). See the Limitations section.

Based on our previous work looking at (negative) growth in substance use (e.g., Parra, Sher, Krull, & Jackson, 2003), we modeled the negative relation between the intercept and the slope factors for all study constructs as a directional relation, rather than as a covariance, in order to address the phenomenon that when modeling negative growth, the higher an individual is at Time 1, the greater he or she falls over time (suggesting perhaps a floor effect for those low at Time 1). Further, modeling the relation between intercept and slope factors as a direct relation allows the authors to describe mediation that is uniquely mediated by the slope of the mediating construct (i.e., cannot be attributed to the respective intercepts of drinking motives).

Parallel analyses on complete-case data yielded similar conclusions to those discussed in the paper.

The intercept for the manifest coping variable at Wave 7 was freely estimated to improve convergence between the observed and estimated means involving coping motives at Wave 7. To ease interpretation in parallel process latent growth models the manifest intercept coping variable at Wave 7 was constrained to be zero. This model also exhibited adequate fit to the data, χ2 [22, n = 483] = 59.10, p<.001; CFI = .96; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .06.

In contrast to the other constructs of interest that exhibited declines across time, coping motives exhibited a slight, statistically non-significant increase from ages 18–35 (see Figure 2). Supplementary analyses that examined linear growth from ages 18–29 for coping motives (i.e., analyses that dropped the last time point) suggested that coping motives significantly declined across this time span (mean slope = −.34, p<.05). Additional analyses that examined linear changes from Waves 5–7 (ages 25–35) indicated that coping motives significantly increased across this time span (mean slope = .68, p<.001). Based on these findings and the examination of mean changes in coping (see Figure 2), coping motives appear to decline from ages 18–29 before increasing until age 35.

Additional analyses were conducted to examine the feasibility of constraining freely estimated slope loadings across growth processes and the influence of the coding of time (i.e., slope loadings) on the conclusions reached in the paper. Chi-square difference testing comparing the constrained (i.e., where the freely estimated slope at the last time point for all study constructs were constrained to be equal) versus unconstrained measurement models suggest equivalence of loadings across processes (χ2 difference = 2.12, df difference = 4, p=.71). Further, a set of parallel analyses to the mediational models presented in the current paper that did not constrain the slope loadings to be equal yielded nearly identical results to those presented and discussed in the paper. Supplementary analyses that examined linear growth from ages 18–29 for all study constructs also yielded results consistent to the findings presented in the paper. Analyses that freely estimated the slope loadings and constrained the intercept and slope covariance to be zero for each construct (see Maydeu-Olivares & Coffman, 2006; Meridith & Tisak, 1990) also resulted in findings consistent with the results presented in the paper.

Parallel analyses that modeled correlated errors among study constructs at each measurement occasion yielded results consistent with the findings and conclusions discussed in the paper.

References

- Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Bryant AL, Merline AC. The decline of substance use in young adulthood: Changes in social activities, roles, and beliefs. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Gailliot M, DeWall CN, Oaten M. Self-regulation and personality: How interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1773–1801. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KH, Thombs DL, Mahoney CA, Fingar KM. Social context and sensation seeking: Gender differences in college student drinking motivations. International Journal of the Addictions. 1995;30:1101–1115. doi: 10.3109/10826089509055830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan D, Cisin IH, Crossley HM. American Drinking Practices: A national study of drinking behavior and attitudes (Monograph no. 6) New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Hasin DS. Drinking to cope with negative affect and DSM-IV alcohol use disorders: A test of three alternative explanations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:694–704. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL. Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:453–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J, MacKinnon DP, Khoo ST. Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10:238–262. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Langenbucher J, Labouvie E, Pandina RJ, Moos RH. Changes in alcoholic patients' coping responses predict 12-month treatment outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:92–100. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. second ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Myths and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos N, Mackie C. Personality-targeted interventions delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Stewart SH, Pihl RO, Côté S, Fontaine V, Dongier M. Efficacy of brief coping skills interventions that match different personality profiles of female substance abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:231–242. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor-model. Psychological Assessments. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1059–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Krull JL, Agocha VB, Flanagan ME, Orcutt HK, Grabe SD, Kurt H, Jackson M. Motivational pathways to alcohol use and abuse among Black and White adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:485–501. doi: 10.1037/a0012592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, George WH. Coping, expectancies, and alcohol abuse: A test of social learning formulations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;92:218–230. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Crews T, Sher KJ. Using Adapted Short MASTs for Assessing Parental Alcoholism: Reliability and Validity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16:427–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin C. Reasons for drinking versus outcome expectancies in the prediction of college student drinking. Substance Use and Misuse. 1997;32:1287–1311. doi: 10.3109/10826089709039379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Gross MM. Alcohol dependence: provisional description of a clinical syndrome. British Medical Journal. 1976;1:1058–1061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6017.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Andreasen N, Spitzer RL. Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Services; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Services; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore KM. Alcohol use across the life course. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Alcoholism and Drug Addiction Research Foundation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ, Morgan-Lopez AA, Howard TL, Browne DC, Flay BR Aban Aya Coinvestigators. Mediators of the Development and Prevention of Violent Behavior. Prevention Science. 2007;8:171–179. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Donovan JE, Costa FM. Beyond adolescence: Problem behavior and young adult development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo ST. Assessing program effects in the presence of treatment-baseline interactions: a latent curve approach. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:234–257. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche EN, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1844–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, von Fischer M, Gmel G. Personality factors and alcohol use: A mediator analysis of drinking motives. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;45:796–800. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist. 2009;64:241–256. doi: 10.1037/a0015309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope, emotional distress and alcohol use and abuse: A ten-year model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:190–198. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope and alcohol use and abuse in unipolar depression: A 10-year model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Cooney NL, Kabela E. Coping skills and treatment outcomes in cognitive–behavioral and interactional group therapy for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:118–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is the “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 118:360–374. doi: 10.1037/a0015125. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007 doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K. Addictive behaviors: New readings on etiology, prevention, and treatment. Washington, DC: US: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT, Jr, Lima MP, Simoes A, Ostendorf F, Angleitner A, et al. Age differences in personality across the adult life span: Parallels in five countries. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:466–477. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally AM, Palfai TP, Levine RV, Moore BM. Attachment dimensions and drinking-related problems among young adults. The mediational role of coping motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1115–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W, Tisak J. Latent curve analysis. Psychometrika. 1990;55:107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide [Computer software and manual] 5th Ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley P. Maturing out of problematic alcohol use. Alcohol Research and Health. 2004/2005;28:202–204. [Google Scholar]

- Parra G, Sher KJ, Krull J, Jackson KM. Frequency of heavy drinking and perceived peer alcohol involvement: Comparison of influence and selection mechanisms from a developmental perspective. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2211–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg J. Developmental Changes in Reasons for Alcohol Use and their Relations with Drinking from Ages 18–30 in the National Monitoring the Future Samples; San Diego, CA. To be presented at the annual meeting of the Research Society for Alcoholism; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Mroczek DK. Personality trait stability and change. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17:31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W. Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:1–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: von Eye A, Clogg CC, editors. Latent variable analysis: Applications for developmental research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Scollon CN, Diener E. Love, work, and changes in extraversion and neuroticism over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:1152–1165. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer M, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1975;36:117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gotham H. Pathological alcohol involvement: A developmental disorder of young adulthood. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:933–956. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gotham HJ, Watson A. Trajectories of dynamic predictors of disorder: Their meanings and implications. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:825–856. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Grekin ER. Alcohol and affect regulation. In: Gross J, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 560–580. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Martinez JA. The future of treatment for substance use: A View from 2009. In: Cohen L, Collins FL, Young AM, McChargue DE, Leffingwell TR, editors. The Pharmacology and Treatment of Substance Abuse: An Evidence-Based Approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Bartholow B, Vieth A. Personality and alcoholism: Issues, methods, and etiological processes. In: Blane H, Leonard K, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2nd edition. New York: Plenum; 1999. pp. 55–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood P, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood M, Crews T, Vandiver TA. The Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire. Reliability and validity studies and derivation of a short form. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Simons J, Correia CJ, Carey KB. A comparison of motives for marijuana and alcohol use among experienced users. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Abbey A, Scott RO. Reasons for drinking alcohol: Their relationship to psychosocial variables and alcohol consumption. International Journal of the Addictions. 1993;28:881–908. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Toneatto T. Recovery from alcohol problems without treatment. In: Heather N, Miller WR, Greeley J, editors. Self-control and the addictive behaviors. New York: Maxwell Macmillan; 1992. pp. 198–242. [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Waller NG. Potential problems with “well fitting” models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:578–598. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson A, Sher KJ. Resolution of alcohol problems without treatment: Methodological issues and future directions of natural recovery research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Windle RC. Coping strategies, drinking motives, and stressful life events among middle adolescents: Associations with emotional and behavioral problems and with academic functioning. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:551–560. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winick C. Maturing out of narcotic addiction. Bulletin on Narcotics. 1962;14:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: That was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist. 2004;59(4):224–235. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Kandel D. On the resolution of role incompatibility: Life event history analysis of family roles and marijuana use. American Journal of Sociology. 1985;90:1284–1325. [Google Scholar]